1 Who’s on First

The Mysteries of Birth Order

IT COULD NOT HAVE BEEN easy being Elliott Roosevelt. If the alcohol wasn’t getting him, the morphine was. If it wasn’t the morphine, it was the struggle with depression. Then, of course, there were the constant comparisons with big brother Teddy.

In 1883, the year Elliott began battling melancholy, Teddy had already published his first book and been elected to the New York State assembly. By 1891—about the time Elliott, still unable to establish a career, had to be institutionalized to deal with his addictions—Teddy was U.S. Civil Service commissioner and the author of eight books. Three years later, Elliott, 34, died of alcoholism. Seven years after that, Teddy, 42, became president.

Elliott Roosevelt was not the only younger sibling of an eventual president to cause his family heartaches—or at least headaches. There was Donald Nixon and the loans he wangled from billionaire Howard Hughes. There was Billy Carter and his advocacy on behalf of the pariah state Libya. There was Roger Clinton and his year in jail on a cocaine conviction. And there was Neil Bush, younger sib of both a president and a governor, implicated in the savings-and-loan scandals of the 1980s and gossiped about after the release of a 2002 email in which he lamented to his estranged wife, “I’ve lost patience for being compared to my brothers.”

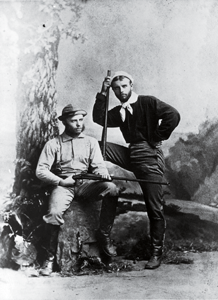

Elliott, seated, and Teddy Roosevelt

Siblings of U.S. presidents endure both being in the shadow of an accomplished, usually older sibling and in the glare of the public eye.

Donald Nixon, in tire, with Richard, top left

Welcome to a very big club, Bro.

Of all the things that shape who we are, few seem more arbitrary than the sequence in which we and our siblings pop out of the womb. Maybe it’s your genes that make you a gifted athlete, your training that makes you an accomplished actress, an accident of brain chemistry that makes you a drunk instead of a president. But in family after family, case study after case study, the simple roll of the birth-date dice has an odd and arbitrary power all its own.

The importance of birth order has been known—or at least suspected—for years. But increasingly, there’s hard evidence of its impact. In 2007, for example, a group of Norwegian researchers released a study showing that firstborns are generally smarter than any siblings who come along later, enjoying on average a three-point IQ advantage over the next eldest—probably a result of the intellectual boost that comes from mentoring younger siblings and helping them in day-to-day tasks. The second child, in turn, is a point ahead of the third. While three points might not seem like much, the effect can be enormous. Just 2.3 IQ points can correlate to a 15-point difference in SAT scores, which makes an even bigger difference when you’re an Ivy League applicant with a 690 verbal score going head to head against someone with a 705. “In many families,” says psychologist Frank Sulloway, a visiting scholar at the University of California, Berkeley, and the man who has for decades been seen as the U.S.’s leading authority on birth order, “the firstborn is going to get into Harvard and the second-born isn’t.”

“I’ve lost patience for being compared to my brothers.”

—NEIL BUSH

While firstborn children are often thought to be smarter than their younger siblings, experts also say that they may feel more pressure to perform.

The differences don’t stop there. Studies in the Philippines show that later-born siblings tend to be shorter and weigh less than earlier-borns. Younger siblings are less likely to be vaccinated than older ones, with last-borns getting immunized sometimes at only half the rate of firstborns. Eldest siblings are also disproportionately represented in high-paying professions. Younger siblings, in contrast, are looser cannons, less educated and less strapping, perhaps, but statistically likelier to live the exhilarating life of an artist or a comedian, an adventurer, entrepreneur, GI or firefighter. And middle children? Well, they can be a puzzle—even to researchers.

For families, none of this comes as a surprise. There are few extended clans that can’t point to the firstborn, with the heir-apparent bearing, who makes the best grades, keeps the other kids in line and, when Mom and Dad grow old, winds up as caretaker and executor too. There are few that can’t point to the lost-in-the-thickets middle-born or the wild-child last-born.

“There are stereotypes out there about birth order, and very often those stereotypes are spot-on,” says Delroy Paulhus, a professor of psychology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. “I think this is one of those cases in which people just figured things out on their own.”

But have they? Stack up enough anecdotal maybes, and they start to look like a scientific definitely. Things that appear definite, however, have a funny way of surprising you, and birth order may conceal all manner of hidden dimensions—within individuals, within families, within the scientific studies.

As recently as 100 years ago, children in the U.S. had only about a 50% chance of surviving into adulthood, and in less developed parts of the world, the odds remain daunting. It can be a sensible strategy to have multiple offspring to continue your line in case some are claimed by disease or injury, and that’s where birth order differences come in.

Eldest siblings are disproportionately represented in high-paying professions.

While the firstborn in an overpopulated brood has it relatively easy—getting 100% of the food the parents have available—things get stretched thinner when a second-born comes along. Later-borns put even more pressure on resources. Over time, everyone might be getting the same rations, but the firstborn still enjoys a caloric head start that might never be overcome.

Food is not the only resource. There’s time and attention too, and the emotional nourishment they provide. It’s not for nothing that family scrapbooks are usually stuffed with pictures and report cards of the firstborn and successively fewer of the later-borns—and the later-borns notice it. Educational opportunities can be unevenly shared, particularly in families that can afford the tuition bills of only one child. Catherine Salmon, an associate professor of psychology at the University of Redlands, laments that even today she finds it hard to collect enough subjects for birth-order studies from the student body alone, since the campus population is typically overweighted with eldest sibs. “Families invest a lot in the firstborn,” she says.

All of this favoritism can become self-reinforcing. As parental pampering produces a fitter, smarter, more confident firstborn, Mom and Dad are likely to invest even more in that child, placing their bets on an offspring who—in survival terms at least—is looking increasingly like a sure thing. “From a parental perspective,” says Salmon, “you want offspring who are going to survive and reproduce.”

43% of CEOs are firstborns, 33% are middle-borns and 23% are last-borns.

Firstborns do more than survive; they thrive. In a 2007 survey of corporate heads conducted by Vistage, an international organization of CEOs, poll takers reported that 43% of the people who occupy the big chair in boardrooms are firstborns, 33% are middle-borns and 23% are last-borns. Eldest siblings are disproportionately represented among surgeons and M.B.A.s too, according to the late Stanford University psychologist Robert Zajonc. And a recent study found a statistically significant overload of firstborns in what is—or at least ought to be—the country’s most august club: the U.S. Congress. “We know that birth order determines occupational prestige to a large extent,” said Zajonc. “There is some expectation that firstborns are somehow better qualified for certain occupations.”

For eldest siblings, this is a pretty sweet deal. There is not much incentive for them to change a family system that provides them so many goodies, and typically they don’t try to. Younger siblings see things differently, and struggle early on to shake up the existing order. They clearly don’t have size on their side, as their physically larger siblings keep them in line with what researchers call a high-power strategy. “If you’re bigger than your siblings, you punch ’em,” Sulloway says.

But there are low-power strategies too, and one of the most effective ones is humor. It’s awfully hard to resist the charms of someone who can make you laugh, and families abound with stories of last-borns who are the clowns of the brood, able to get their way simply by being funny or outrageous. Birth-order scholars often observe that some of history’s great satirists—Voltaire, Jonathan Swift, Mark Twain—were among the youngest members of large families.

It’s awfully hard to resist the charms of someone who can make you laugh, and families abound with stories of last-borns who are the clowns of the brood, able to get their way simply by being funny or outrageous.

Such examples might be little more than anecdotal, but personality tests show that while firstborns score especially well on the dimension of temperament known as conscientiousness—a sense of general responsibility and follow-through—later-borns score higher on what’s known as agreeableness, or the simple ability to get along in the world. “Kids recognize a good low-power strategy,” says Sulloway. “It’s the way any sensible organism sizes up the niches that are available.”

Birth-order scholars often observe that some of history’s great satirists were among the youngest members of large families.

Voltaire

Jonathan Swift

Mark Twain

Even more impressive is how early younger siblings develop what’s known as the theory of mind. Very small children have a hard time distinguishing the things they know from the things they assume other people know. A toddler who watches an adult hide a toy will expect that anyone who walks into the room afterward will also know where to find it, reckoning that all knowledge is universal knowledge. It usually takes a child until age 3 to learn that that’s not so. For children who have at least one elder sibling, though, the realization typically comes earlier. “When you’re less powerful, it’s advantageous to be able to anticipate what’s going on in someone else’s mind,” says Sulloway.

Later-borns, however, don’t try merely to please other people; they also try to provoke them. Richard Zweigenhaft, a professor of psychology at Guilford College who revealed the overrepresentation of firstborns in Congress, conducted a similar study of picketers at labor demonstrations. On the occasions that the events grew unruly enough to lead to arrests, he would interview the people the police rounded up. Again and again, he found, the majority were later- or last-borns. “It was a statistically significant pattern,” says Zweigenhaft. “A disproportionate number of them were choosing to be arrested.”

Later-borns are similarly willing take risks with their physical safety. All sibs are equally likely to be involved in sports, but younger ones are likelier to choose the kinds that could cause injury. “They don’t go out for tennis,” Sulloway says. “They go out for rugby, ice hockey.”

It’s not clear whether such behavior extends to career choice, but Sandra Black, a professor of economics at the University of Texas, is intrigued by findings that firstborns tend to earn more than later-borns, with income dropping about 1% for every step down the birth-order ladder. Most researchers assume this is due to the educational advantages eldest siblings get, but Black thinks there may be more to it. “I’d be interested in whether it’s because the second child is taking the riskier jobs,” she says.

Research by Ben Dattner, a business consultant who teaches industrial and organizational psychology at New York University, is showing that even when later-borns take conservative jobs in the corporate world, they approach their work in a high-wire way. Firstborn CEOs, for example, do best when they’re making incremental improvements in their companies: shedding underperforming products, maximizing profits from existing lines and generally making sure the trains run on time. Later-born CEOs are more inclined to blow up the trains and lay new track. “Later-borns are better at transformational change,” says Dattner. “They pursue riskier, more innovative, more creative approaches.”

If eldest sibs are the dogged achievers and youngest sibs are the gamblers and visionaries, where does this leave those in between? That it’s so hard to define what middle-borns become is largely due to the fact that it’s so hard to define who they are growing up. The youngest in the family, but only until someone else comes along, they are both teacher and student, babysitter and babysat, too young for the privileges of the firstborn but too old for the latitude given the last. Middle children are expected to step up to the plate when the eldest child goes off to school or in some other way drops out of the picture—and generally serve when called. The Norwegian intelligence study showed that when firstborns die, the IQ of second-borns actually rises a bit, a sign that they’re performing the hard mentoring work that goes along with the new job.

Stuck for life in a center seat, middle children get shortchanged even on family resources. Unlike the firstborn, who spends at least some time as the only-child eldest, and the last-born, who hangs around long enough to become the only-child youngest, middlings are never alone and thus never get 100% of the parents’ investment of time and money. “There is a U-shaped distribution in which the oldest and youngest get the most,” says Sulloway. That may take an emotional toll. Sulloway cites other studies in which the self-esteem of first-, middle- and last-borns is plotted on a graph and follows the same curvilinear trajectory.

The phenomenon known as de-identification may also work against a middle-born. Siblings who hope to stand out in a family often do so by observing what the elder child does and then doing the opposite. If the firstborn gets good grades and takes a job after school, the second-born may go the slacker route. The third-born may then de-de-identify, opting for industriousness, even if in the more unconventional ways of the last-born. A Chinese study in the 1990s showed just this kind of zigzag pattern, with the first child generally scoring high as a “good son or daughter,” the second scoring low, the third scoring high again and so on. In a three-child family, the very act of trying to be unique may instead leave the middling lost, a pattern that may continue into adulthood.

The birth-order effect, for all its seeming robustness, is not indestructible. There’s a lot that can throw it out of balance—particularly family dysfunction. In a 2005 study, investigators at the University of Birmingham in Britain examined the case histories of 400 abused children and the 795 siblings of those so-called index kids. In general, they found that when only one child in the family was abused, the scapegoat was usually the eldest. When a younger child was abused, some or all of the other kids usually were as well. Mistreatment of any of the children usually breaks the bond the parents have with the firstborn, turning that child from parental ally to protector of the brood. At the same time, the eldest may pick up some of the younger kids’ agreeableness skills—the better to deal with irrational parents—while the youngest learn some of the firstborn’s self-sufficiency. Abusiveness is going to “totally disrupt the birth-order effects we would expect,” says Sulloway.

Judging by the look on his face, this little one, left, is typical of youngest children in their love of more dangerous and risky pursuits such as ice hockey.

Middlings are never alone and thus never get 100% of the parents’ investment of time and money.

Middle children often feel stuck between the oldest, who probably has more privileges, and the youngest, who may well get away with murder.

The sheer number of siblings in a family can also trump birth order. The 1% income difference that Black detected from child to child tends to flatten out as you move down the age line, with a smaller earnings gap between a third and fourth child than between a second and third. The IQ-boosting power of tutoring, meanwhile, may actually have less influence in small families, with parents of just two or three kids doing most of the teaching, than in the six- or eight-child family, in which the eldest sibs have to pitch in more. Since the Norwegian IQ study rests on the tutoring effect, those findings may be open to question. “The good birth-order studies will control for family size,” says Bo Cleveland, an associate professor of human development and family studies at Penn State University. “Sometimes that makes the birth-order effect go away; sometimes it doesn’t.”

The most vocal detractors of birth-order research question less the findings of the science than the methods. To achieve any kind of statistical significance, investigators must assemble large samples of families and look for patterns among them. But families are very different things—distinguished by size, income, hometown, education, religion, ethnicity and more. Throw enough random factors like those into the mix, and the results you get may be nothing more than interesting junk.

The alternative is what investigators call the in-family studies, a much more pointillist process, requiring an exhaustive look at a single family, comparing every child with every other child and then repeating the process again and again with hundreds of other families. Eventually, you may find threads that link them all. “I would throw out all the between-family studies,” says Cleveland. “The proof is in the in-family design.”

Ultimately, of course, the birth-order debate will never be entirely settled. Family studies and the statistics they yield are cold and precise things, parsing human behavior down to decimal points and margins of error. But families are a good deal sloppier than that, a mishmash of competing needs and moods and clashing emotions, better understood by the people in the thick of them than by anyone standing outside. Yet millennia of families would swear by the power of birth order to shape the adults we eventually become. Science may yet overturn the whole theory, but for now, the smart money says otherwise.

There were originally 11 Hurlburt siblings, eight of whom lived into old age and several of whom are still alive. Peggy, far left, is the youngest; Agnes, second from right, the oldest, celebrated her 100th birthday in 2013.

Firstborn

Working hard and meeting goals

They are the smartest of the bunch, bossy and confident. Firstborns play by the rules and become strong leaders—or not. But more than half of all U.S. presidents have been firstborns, as well as 21 of the first 23 astronauts, so the experts may be on to something.

Bill Clinton and Hillary Clinton

Jimmy Carter

Kate Middleton

Barack Obama

Steve Jobs

Lena Dunham

Oprah Winfrey

Clint Eastwood

Rush Limbaugh

Dan Rather

J.K. Rowling

Middle-Born

Feeling the squeeze from both sides

It can be frustrating trying to compete with an older sibling, and equally frustrating trying to get as much attention as the baby of the family. Either way, middle children often feel as though they are left to figure things out by themselves. As these examples show, they do that in wildly different ways.

Martin Luther King Jr.

Princess Diana

Bill Gates

Peyton Manning

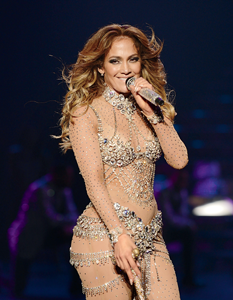

Jennifer Lopez

Madonna

Richard Nixon

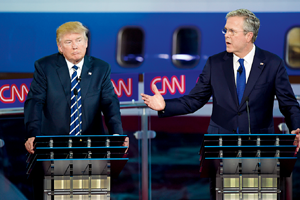

Donald Trump and Jeb Bush

Kim Kardashian

Last-Born

Seeking thrills and spreading charm

Young children have a sixth sense for which parts have already been taken in the family play, so the youngest child often works hard to be something that his older siblings are not. That often turns out to be engaging, witty and willing to take risks, which is why so many of them are actors and entertainers.

George Clooney

Jennifer Lawrence

Eddie Murphy

Angelina Jolie

Tom Brady

Johnny Depp

Matt Damon

Mozart

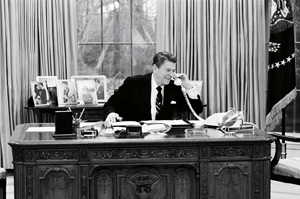

Ronald Reagan

Eli Manning

Ted Kennedy

Bernie Sanders

How Birth Order Will Shape the Royal Princess

It’s never easy being a second-born—especially when your big brother is going to be king

Dear Princess Charlotte:

You’re having some kind of first year, what with the entire planet swooning and making strange smoochy noises at the mere sight of you. It’s all good, and the last thing I want to be is the skunk at the monarchical picnic, but there’s one detail you might as well learn about now. His name is George—or Georgie, as all those smoochy people call him—and he’s got plans for you.

George is your big brother. He’s only 2½ years old and the world finds him adorable, but you won’t—for a lot of reasons. For starters, at some point in your childhood he will sit on your head. Actually, at a lot of points in your childhood he will sit on your head, and there is absolutely nothing you can do about it. The main problem with George is not that he’s third in line to the throne and you’re fourth. That just happens to be one of the downsides of your family business. The problem is one that’s familiar to the rest of us serfs and colonists: he’s the firstborn, and you’re not.

Your mom and your dad—lovely people, by all accounts—are no different from other parents when it comes to baby-making; they’re ruled by their genes, and genes are greedy. The only thing they want is to be reproduced over and over again. That makes moms and dads want to have lots of babies, which is good, but they don’t treat all those babies exactly the same.

The firstborn—Georgie, in your case—gets a head start on food, attention, medical care, education and more. Before the second-born—you, in your case—even comes along, all that TLC makes the big sibling a better bet to survive childhood, grow up and have babies of his own, which makes the genes smile. In your family, of course, there’s plenty of food, money and other resources to go around, but back in the days of one of your many royal grandpas—let’s say Edward III, who had the rotten luck to be in office in 1348, when the black plague was making its rounds—surviving childhood wasn’t such a sure thing.

So moms and dads, who have already invested a lot of resources in the firstborn, tend to favor that child, with later ones getting what’s left over. Corporations call this “sunk costs” (you’ll learn about this at Eton). In the case of the monarchy, it’s called “an heir and a spare,” but you didn’t hear that from me.

This is an arrangement that suits that first product just fine, which is why big brothers and sisters tend to play by the rules. Your job—and the job of any littler royals who may come along after you—will be to try to upset that order. It’s why later-borns tend to be more rebellious and to take more risks than firstborns. You’ll be likelier to play extreme sports than big bro George. Even if you and he play the same sports, you’ll choose a more physical position—say, catcher instead of pitcher in baseball (which is a sport like cricket except the bat is narrower and the ball moves faster and there’s this thing called the infield fly rule and . . . never mind). In the event you ever become Ruler of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and other Realms and Territories around the world, you will be a more liberal, less conventional monarch than your big bro would be.

Later-borns are more inclined to be artists too, and if there is a comedian in the family, it’s likeliest to be the very last born. This makes sense, since when you’re the smallest person in the nursery, you are at constant risk of getting clocked by someone bigger, so you learn to disarm with humor. As you get older, other perils await—ones that are especially problematic for royal families. You don’t really know your grandpa Charles yet, but you’ll find he’s a pretty well-behaved guy (OK, there was the thing with grandmum Camilla, but that’s for him to explain to you). The same is true of your dad. How come? Because they’re both going to be king one day.

As for your uncle Harry? Ask him what he wears to Halloween parties (not good) or to play pool in Las Vegas hotel rooms (not much). And if he hasn’t always been the picture of royal reserve, well, neither have your great-grandpa Phillip or your great-uncle Andrew. That’s what comes from having lots of money, too much free time, and being really, really close to the throne but never getting to sit on it.

None of this is for you to worry about yet. Even royal babies are just babies, so for now, sleep in, fatten up and hang with Mom as much as you can—especially if it keeps your dad away from her. Trust me, the middle-child gig is even worse.