structure political understanding and so set goals and inspire activism

structure political understanding and so set goals and inspire activismPREVIEW

All people are political thinkers. Whether they know it or not, people use political ideas and concepts whenever they express their opinion or speak their mind. Everyday language is littered with terms such as ‘freedom’, ‘fairness’, ‘equality’, ‘justice’ and ‘rights’. In the same way, words such as ‘conservative’, ‘liberal’, ‘socialist’, ‘communist’ and ‘fascist’ are regularly employed by people to describe either their own views, or those of others. However, even though such terms are familiar, even commonplace, they are seldom used with any precision or a clear grasp of their meaning. What, for instance, is ‘equality’? What does it mean to say that all people are equal? Are people born equal; should they be treated by society as if they are equal? Should people have equal rights, equal opportunities, equal political influence, equal wages? Similarly, words such as ‘socialist’, ‘nationalist’ and ‘feminist’ are commonly misused. What does it mean to call someone a ‘nationalist’? What values or beliefs do nationalists hold, and why do they hold them? How do socialist views differ from those of, say, liberals, conservatives or anarchists?

This introductory chapter examines, first, the role of political ideas, together with rival views about the relationship in political life between, on the one hand, values, doctrines and beliefs and, on the other hand, the material world and the quest for power. Do political ideas ‘make’ the world in which we live, or are they merely a reflection of that world? Second, it considers the nature of the ideological traditions that have done so much to shape political thinking in general and, most specifically, to determine the meaning (and, all too frequently, the meanings) of political ideas. What are political ideologies and why do they matter? Third, it examines the significance and implications of the distinction between left-wing ideas and right-wing ideas. Do the notions of left and right sharpen political thinking, or do they simply cause confusion?

This book examines political ideas from the perspective of the key ideological traditions. It focuses, in particular, on the ‘traditional’, or ‘core’, ideologies (liberalism, conservatism and socialism, which are examined in Part 1), but it also considers a range of other ideological traditions, which have arisen either out of, or in opposition to, the traditional ones (anarchism, nationalism, feminism, ecologism and multiculturalism, which are examined in Part 2).

However, not all political thinkers have accepted that ideas and ideologies are of much importance. Politics has sometimes been thought to be little more than a naked struggle for power. If this is true, political ideas are mere propaganda, a form of words or collection of slogans designed to win votes or attract popular support. Ideas and ideologies are therefore simply ‘window dressing’, used to conceal the deeper realities of political life. The opposite argument has also been put, however. The UK economist John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), for example, argued that the world is ruled by little other than the ideas of economic theorists and political philosophers. As he put it in the closing pages of his General Theory:

Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back. (Keynes, [1936] 1963)

This position highlights the degree to which beliefs and theories provide the wellspring of human action. The world is ultimately ruled by ‘academic scribblers’. Such a view suggests, for instance, that modern capitalism (see p. 62) developed, in important respects, out of the classical economics of Adam Smith (1723–90) and David Ricardo (1772–1823), that Soviet communism was shaped significantly by the writing of Karl Marx (see p. 67) and V. I. Lenin (1870–1924), and that the history of Nazi Germany can only be understood by reference to the doctrines advanced in Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf (1925).

In reality, both of these accounts of political life are one-sided and inadequate. Political ideas are not merely a passive reflection of vested interests or personal ambition, but have the capacity to inspire and guide political action itself and so to shape material life. At the same time, political ideas do not emerge in a vacuum: they do not drop from the sky like rain. All political ideas are moulded by the social and historical circumstances in which they develop and by the political ambitions they serve. Quite simply, political thought and political practice are inseparably linked. Any balanced and persuasive account of political life must therefore acknowledge the constant interplay between ideas and ideologies on the one hand, and historical and social forces on the other.

Ideas and ideologies influence political life in a number of ways. They:

structure political understanding and so set goals and inspire activism

structure political understanding and so set goals and inspire activism

shape the nature of political systems

shape the nature of political systems

act as a form of social cement.

act as a form of social cement.

In the first place, ideologies provide a perspective, or ‘lens’, through which the world is understood and explained. People do not see the world as it is, but only as they expect it to be: in other words, they see it through a veil of ingrained beliefs, opinions and assumptions. Whether consciously or subconsciously, everyone subscribes to a set of political beliefs and values that guide their behaviour and influence their conduct. Political ideas and ideologies thus set goals that inspire political activism. In this respect, politicians are subject to two very different influences. Without doubt, all politicians want power. This forces them to be pragmatic, to adopt those policies and ideas that are electorally popular or win favour with powerful groups, such as business or the military. However, politicians seldom seek power simply for its own sake. They also possess beliefs, values and convictions (if to different degrees) about what to do with power when it is achieved.

Second, political ideologies help to shape the nature of political systems. Sys-tems of government vary considerably throughout the world and are always associated with particular values or principles. Absolute monarchies were based on deeply established religious ideas, notably the divine right of kings. The political systems in most contemporary western countries are founded on a set of liberal-democratic principles. Western states are typically founded on a commitment to limited and constitutional government, as well as the belief that government should be representative, in the sense that it is based on regular and competitive elections. In the same way, traditional communist political systems conformed to the principles of Marxism–Leninism. Even the fact that the world is divided into a collection of nation-states and that government power is usually located at the national level reflects the impact of political ideas, in this case of nationalism and, more specifically, the principle of national self-determination.

Finally, political ideas and ideologies can act as a form of social cement, providing social groups, and indeed whole societies, with a set of unifying beliefs and values. Political ideologies have commonly been associated with particular social classes – for example, liberalism with the middle classes, conservatism with the landed aristocracy, socialism with the working class, and so on. These ideas reflect the life experiences, interests and aspirations of a social class, and therefore help to foster a sense of belonging and solidarity. However, ideas and ideologies can also succeed in binding together divergent groups and classes within a society. For instance, there is a unifying bedrock of liberal-democratic values in most western states, while in Muslim countries Islam has established a common set of moral principles and beliefs. In providing society with a unified political culture, political ideas help to promote order and social stability. Nevertheless, a unifying set of political ideas and values can develop naturally within a society, or it can be enforced from above in an attempt to manu-facture obedience and exercise control. The clearest examples of such ‘official’ ideologies have been found in fascist, communist and religious fundamentalist regimes.

UNDERSTANDING POLITICAL IDEOLOGIES

Ideology is one of those controversial concepts encountered in political analysis. Although the term now tends to be used in a neutral sense, to refer to a developed social philosophy or ‘world-view’, it has in the past had heavily negative or pejorative connotations. During its sometimes tortuous career, the concept of ideology has commonly been used as a political weapon with which to condemn or criticise rival creeds or doctrines.

The term ‘ideology’ was coined in 1796 by the French philosopher Destutt de Tracy (1754–1836). He used it to refer to a new science of ideas (literally, an idea-ology) that set out to uncover the origins of conscious thought and ideas. De Tracy’s hope was that ideology would eventually achieve the same status as established sciences such as zoology and biology. However, a more enduring meaning was assigned the term in the nineteenth century in the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (see p. 72). For Marx and Engels, ideology amounted to the ideas of the ruling class, ideas that therefore uphold the class system and perpetuate exploitation. In their early work, The German Ideology, Marx and Engels wrote the following:

The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class which is the ruling material force in society is, at the same time, the ruling intellectual force. The class which has the means of mental production at its disposal, has control at the same time over the means of production. (Marx and Engels, [1846] 1970)

The defining feature of ideology in the Marxist sense is that it is false: it mystifies and confuses subordinate classes by concealing from them the contradictions on which all class societies are based. As far as capitalism is concerned, the ideology of the property-owning bourgeoisie (bourgeois ideology) fosters delusion or ‘false consciousness’ among the exploited proletariat, preventing them from recognising the fact of their own exploitation. Nevertheless, Marx and Engels did not believe all political views had an ideological character. They held that their work, which attempted to uncover the process of exploitation and oppression, was scientific. In this view, a clear distinction could be drawn between science and ideology, between truth and falsehood. This distinction tended, however, to be blurred in the writings of later Marxists such as the Bolshevik leader V. I. Lenin (1870–1924) and the Italian revolutionary and political theorist Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937). These referred not only to ‘bourgeois ideology’, but also to ‘socialist ideology’ or ‘proletarian ideology’, terms that Marx and Engels would have considered absurd.

Key concept … IDEOLOGY

From a social-scientific viewpoint, an ideology is a more or less coherent set of ideas that provides a basis for organised political action, whether this is intended to preserve, modify or overthrow the existing system of power relationships. All ideologies therefore (1) offer an account of the existing order, usually in the form of a ‘world-view’, (2) provide a model of a desired future, a vision of the ‘good life’, and (3) outline how political change can and should be brought about. Ideologies are not, however, hermetically sealed systems of thought; rather, they are fluid sets of ideas that overlap with one another at a number of points.

Alternative uses of the term have been developed by liberals and conservatives. The emergence of totalitarian dictatorships in the inter-war period encouraged writers such as Karl Popper (1902–94), J. L. Talmon (1916–80) and Hannah Arendt (1906–75) to view ideology as an instrument of social control designed to bring about compliance and subordination. Relying heavily on the examples of fascism and communism, this Cold War liberal use of the term treated ideology as a ‘closed’ system of thought, which, by claiming a monopoly of truth, refuses to tolerate opposing ideas and rival beliefs. In contrast, liberalism, based as it is on a fundamental commitment to individual freedom, and doctrines such as conservatism and democratic socialism that broadly subscribe to liberal principles, are clearly not ideologies. These doctrines are ‘open’ in the sense that they permit, and even insist on, free debate, opposition and criticism. A distinctively conservative use of the term ideology has been developed by thinkers such as Michael Oakeshott (see p. 37). This view reflects a characteristically conservative scepticism about the value of rationalism (see p. 13), born out of the belief that the world is largely beyond the capacity of the human mind to fathom.

LEFT- AND RIGHT-WING IDEAS

The origins of the terms ‘left’ and ‘right’ in politics date back to the French Revolution and the seating arrangements of radicals and aristocrats at the first meeting of the Estates General in 1789. The left/right divide therefore originally reflected the stark choice between revolution and reaction. The terms have subsequently been used to highlight a divide that supposedly runs throughout the world of political thought and action, helping both to provide insight into the nature of particular ideologies and to uncover relationships between political ideologies more generally. Left and right are usually understood as the poles of a political spectrum, enabling people to talk about the ‘centre-left’, the ‘far right’ and so on. This is in line with a linear political spectrum that travels from left-wing to right-wing, as shown in Figure 1.1. However, the terms left and right have been used to draw attention to a variety of distinctions.

Stemming from their original meanings, left and right have been used to sum up contrasting attitudes to political change in general, left-wing thinking wel-coming change, usually based on a belief in progress, while right-wing thinking resists change and seeks to defend the status quo. Inspired by works such as Theodor Adorno et al.’s The Authoritarian Personality (1950), attempts have been made to explain ideological differences, and especially rival attitudes to change, in terms of people’s psychological needs, motives and desires (Jost et al., 2003). In this light, conservative ideology, to take one example, is shaped by a deep psychological aversion to uncertainty and instability (an idea examined in Chapter 3). An alternative construction of the left/right divide focuses on different attitudes to economic organisation and the role of the state. Left-wing views thus support intervention and collectivism (see p. 64), while right-wing views favour the market and individualism (see p. 12). Bobbio (1996), by contrast, argued that the fundamental basis for the distinction between left and right lies in differing attitudes to equality, left-wingers advocating greater equality while right-wingers treat equality as either impossible or undesirable. This may also help to explain the continuing relevance of the left/right divide, as the ‘great problem of inequality’ remains unresolved at both national and global levels.

Progress: Moving forward; the belief that history is characterised by human advancement underpinned by the accumulation of knowledge and wisdom.

Status quo: The existing state of affairs.

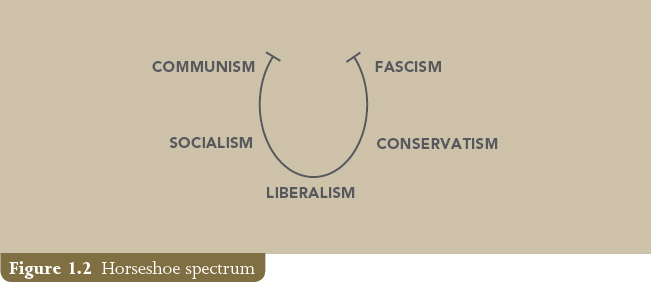

As a means of providing insight into the character of political ideas and ideologies and how they relate to one another, the traditional linear political spectrum nevertheless has a range of drawbacks. For example, the ideologies that are traditionally placed at the extreme wings of the linear spectrum may have more in common with one another than they do with their ‘centrist’ neighbours. During the Cold War period in particular, it was widely claimed that communism and fascism resembled one another by virtue of a shared tendency towards totalitarianism. Such a view led to the idea that the political spectrum should be horseshoe-shaped, not linear (see Figure 1.2).

Totalitarianism: An all-encompassing system of political rule, typically established by pervasive ideological manipulation and open terror.

Moreover, as political ideologies are fluid entities, capable, some would argue, of almost constant re-invention, our notions of left and right must be regularly updated. This fluidity can be seen in the case of reformist socialist parties in many parts of the world, which, since the 1980s, have tended to distance themselves from a belief in nationalisation and welfare and, instead, embrace market economics. The implication of this for the left/right divide is either that reformist socialism has shifted to the right, moving from the centre-left to the centre-right, or that the spectrum itself has shifted to the right, redefining reformist socialism, and therefore leftism, in the process.

Finally, as ideological debate has developed and broadened over the years, the linear spectrum has seemed increasingly simplistic and generalised, the left/ right divide only capturing one dimension of a more complex series of political interactions. This has given rise to the idea of the two-dimensional spectrum, with, as pioneered by Hans Eysenck (1964), a liberty/authority vertical axis being added to the established left/right horizontal axis (see Figure 1.3).

Festenstein, M. and Kenny, M. (eds), Political Ideologies: A Reader and Guide (2005). A very useful collection of extracts from key texts on ideology and ideologies, supported by lucid commentaries.

Freeden, M., Ideology: A Very Short Introduction (2004). An accessible and lively introduction to the concept: an excellent starting place.

Freeden, M. et al., The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies (2015). A wide-ranging, up-to-date and authoritative account of debates about the nature of ideology and the shape of the various ideological traditions.

McLellan, D., Ideology (1995). A clear and short yet comprehensive introduction to the concept of ideology.