One

THE NATURAL SETTING

San Juan [now Dana Point] is the only romantic spot in California. The country here for several miles is high table-land, running boldly to the shore, and breaking off in a steep hill, at the foot of which the waters of the Pacific are constantly dashing. For several miles the water washes the very base of the hill, or breaks upon ledges and fragments of rocks which run out into the sea.

—Richard Henry Dana Two Years Before the Mast

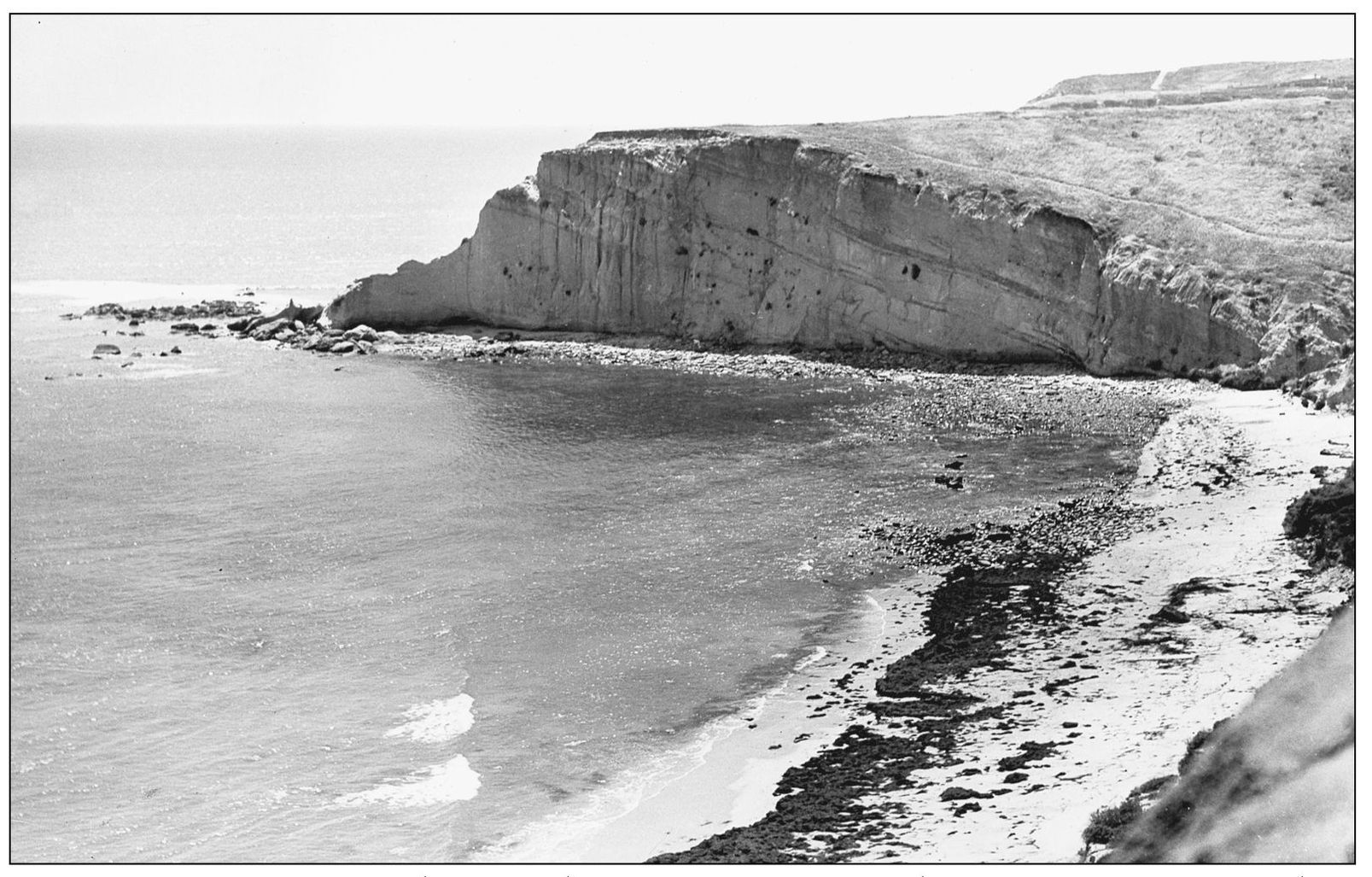

GREAT ROCK WALL. Most of the more than 7-mile coast of today’s City of Dana Point is set upon high marine terraces that were once segments of the ocean floor, uplifted eons ago by cataclysmic earth eruptions. The terraces south of the headlands within Dana Point Harbor continue up to today’s Doheny State Beach. The city’s modern residential neighborhoods offer varying vistas of the seacoast, the Capistrano Valley, and the Santa Ana Mountains.

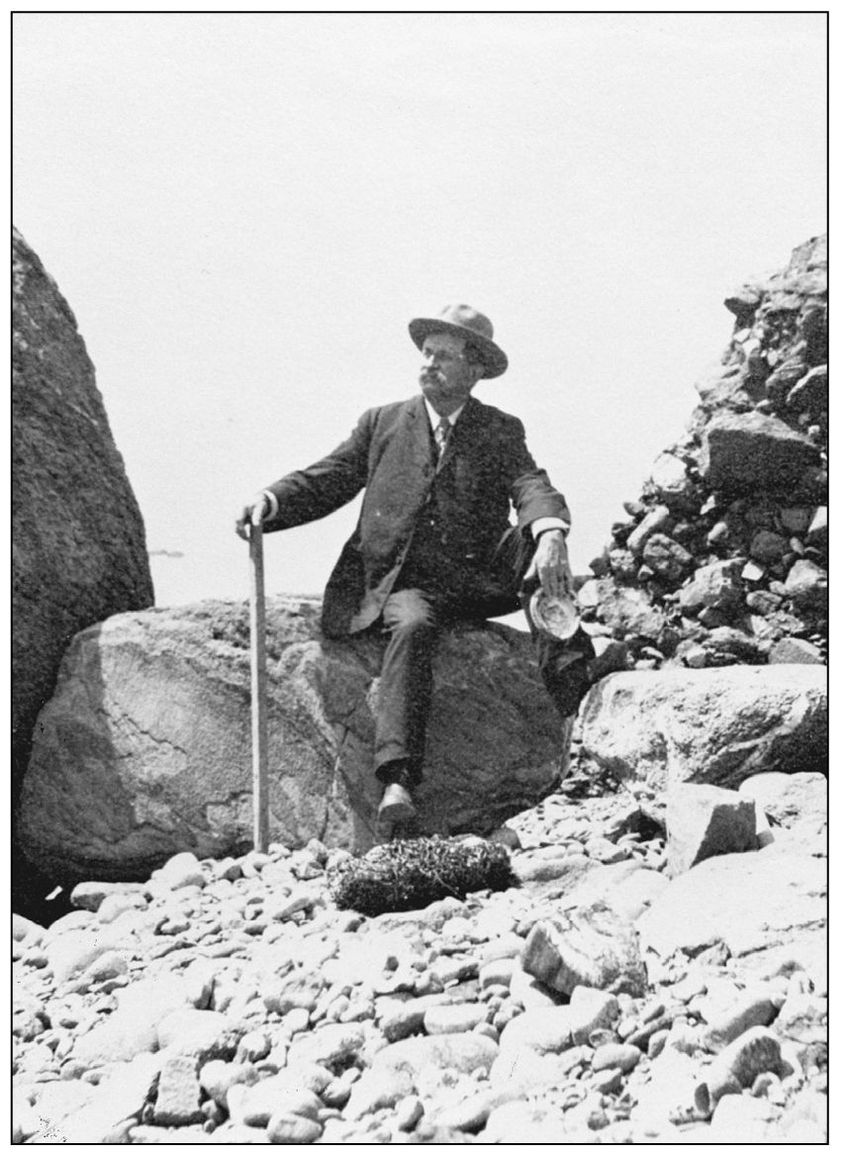

ROCKY REACHES. This early 20th-century visitor, while passing though, chose to be photographed within a rocky coastal setting. He holds the shell of an abalone, a species quite abundant and sought after along the south Orange County coast in those days. Because the bluffs were then uniformly planted with lima beans from Irvine to Oceanside, the only access to an ocean view would have been achieved by walking between the rigid rows of plants.

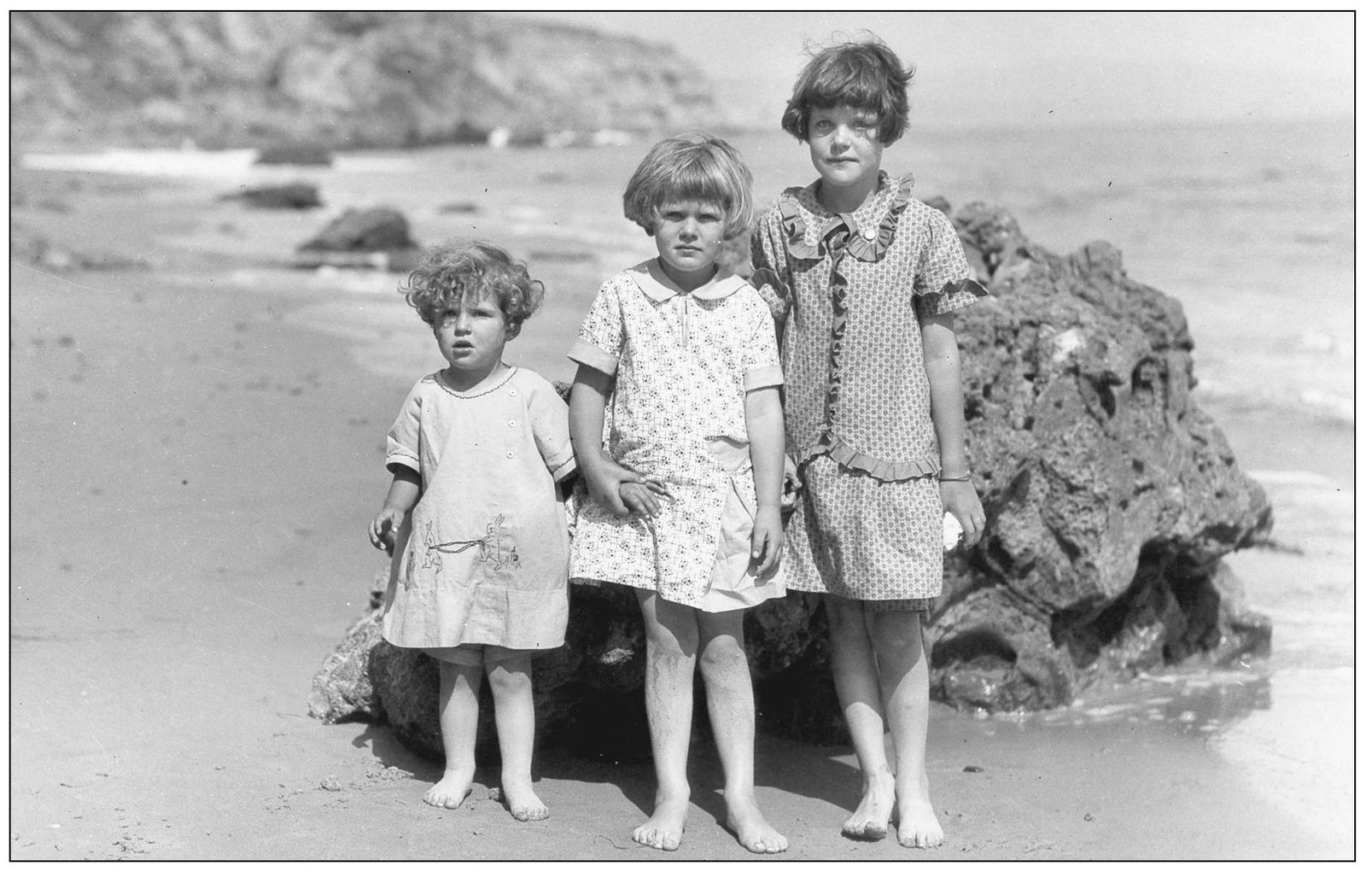

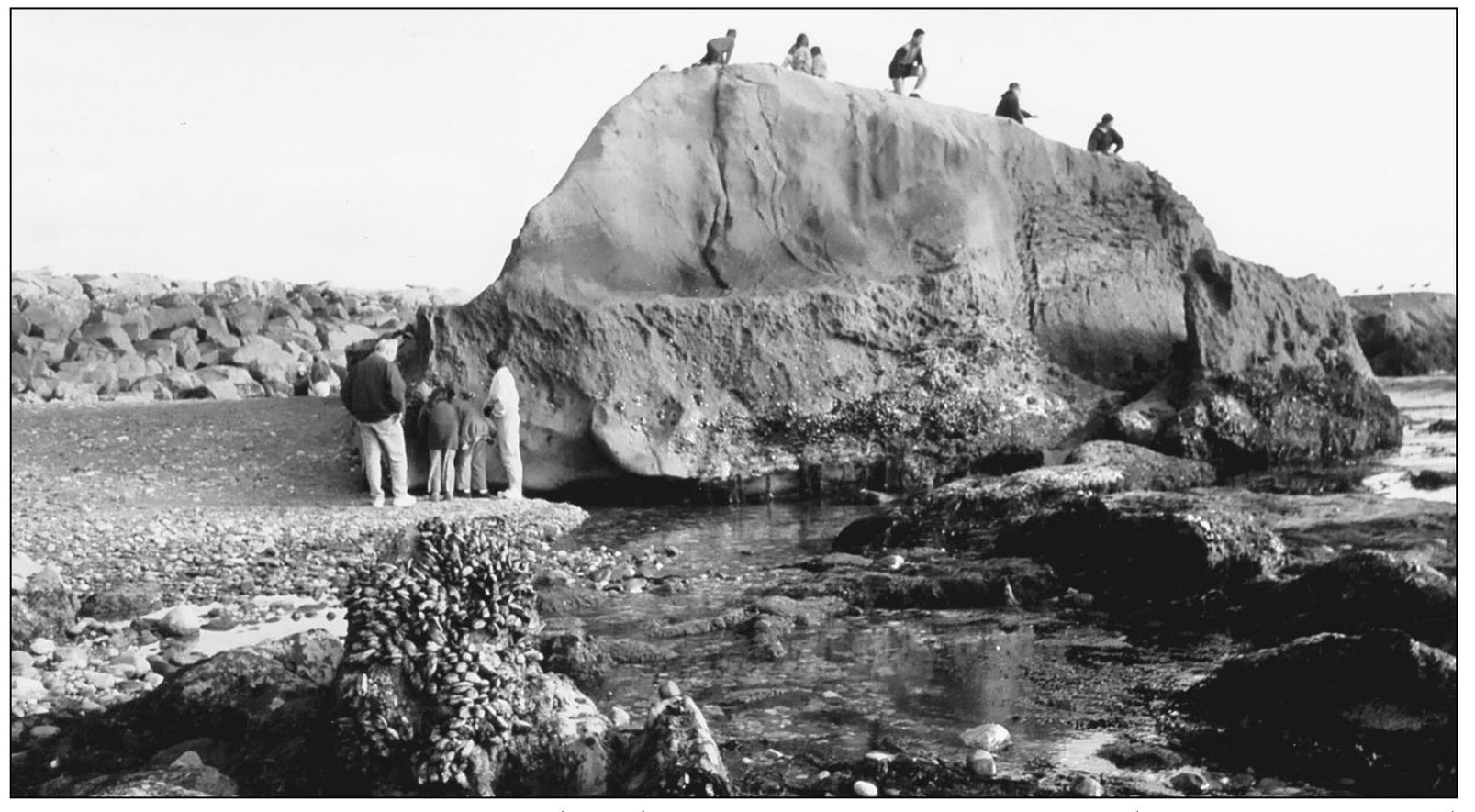

ANCIENT ROCK AND YOUNG ADMIRERS, 1920s. The rocks that circle the coves of Dana Point are a special focus for geologists. This huge boulder fell from the oldest formation of all, the Dana Point headlands. It is formed of angular rocks cemented within a hard matrix. They include rare schist rock formed about 150 million years ago. A walk along the base of the headlands reveals this blue schist embedded within a rosy-colored foundation.

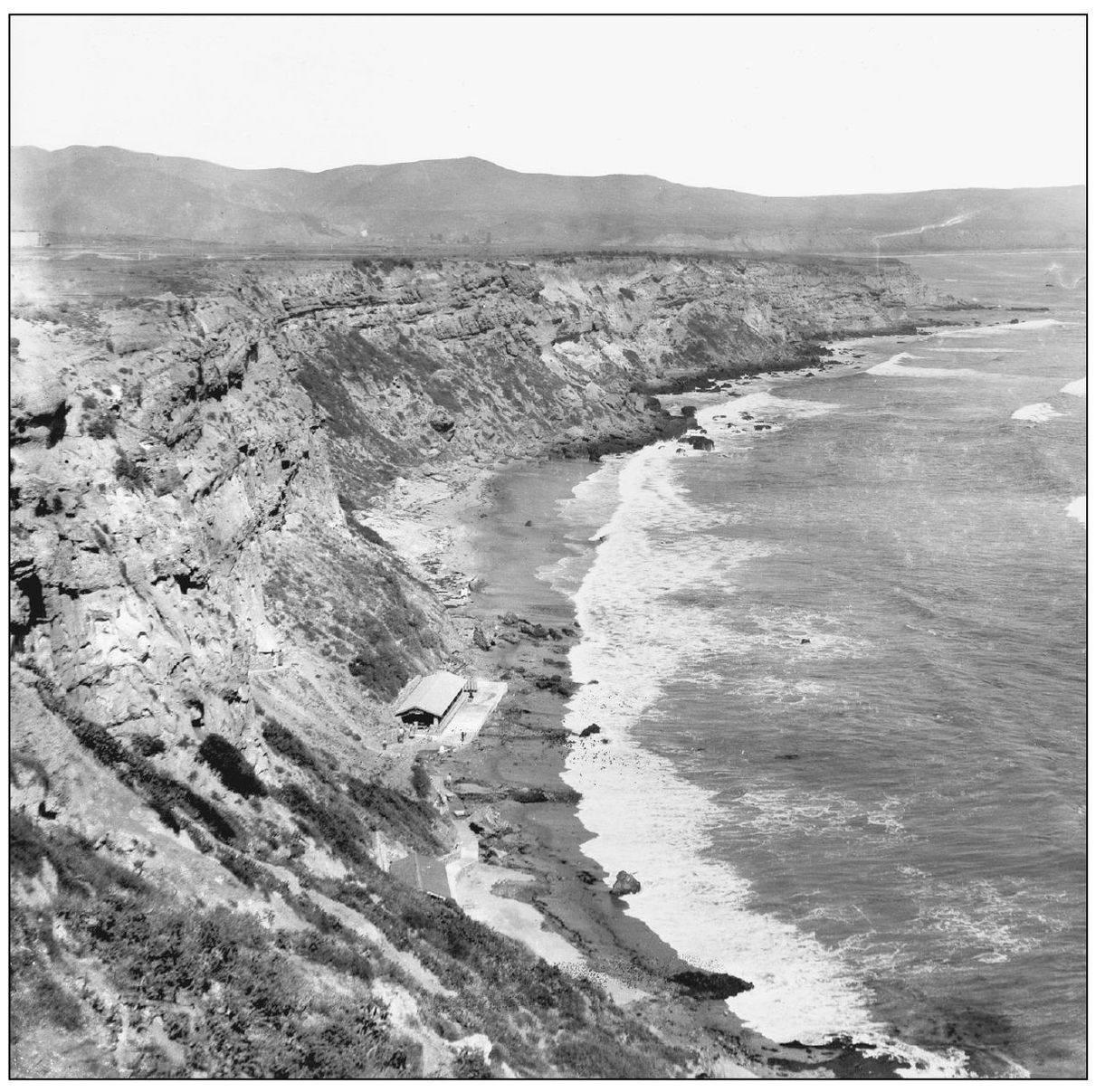

SCENIC INN, 1924. Though there was no natural access to the narrow, rocky beach at the foot of the Dana Cove cliffs, and despite its isolation at high tide, the first planned development on the bluff-tops had this secluded Scenic Inn built of native beach rock. The shelter was an enticement for hardy lot shoppers, who were served promotional picnics that featured local lobster. A winding foot trail cut along the bluff-side gave access to this glorious scene.

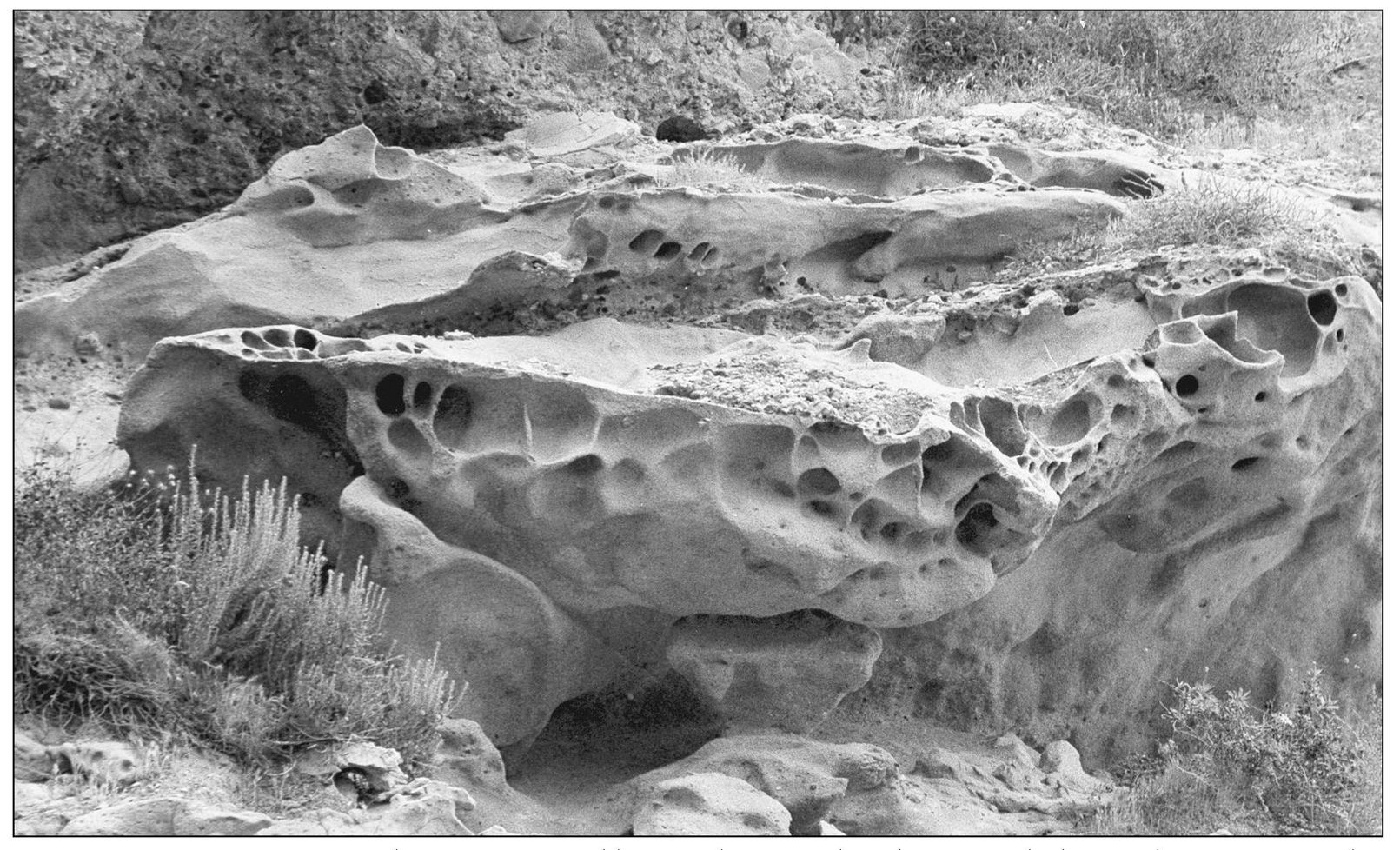

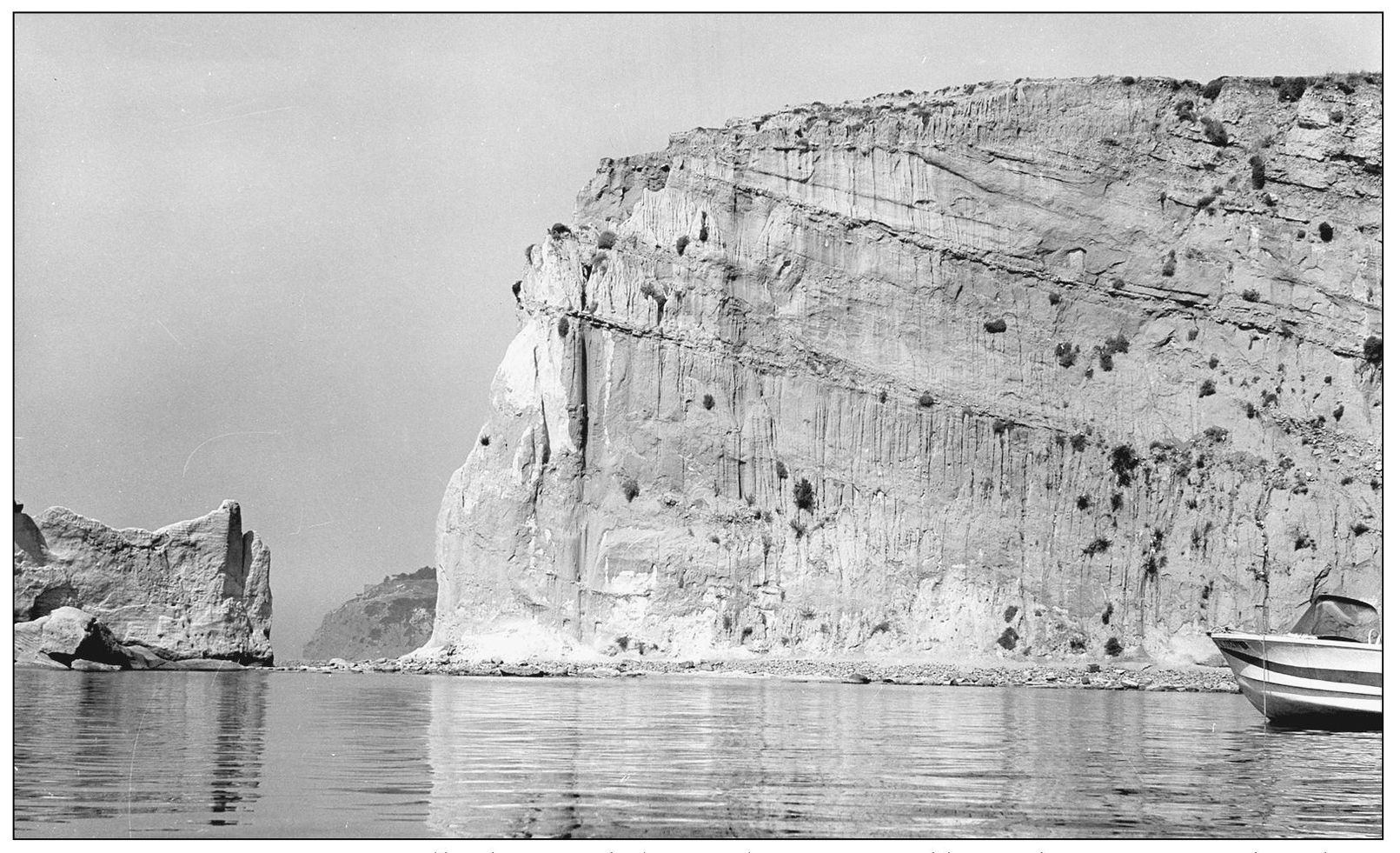

PICTURESQUE EROSION. The fine-grained beige siltstone cliffs have eroded over the ages from the forces of wind and weather, magnifying their beauty to the beholder. Pockets in their pleasingly eroded sides become natural flowerpots for rare native succulents. The swallows that brought romance to nearby Mission San Juan Capistrano once built their nests in the orifices of Dana Point’s oceanfront cliffs, hence their name “cliff swallows.” (Photograph by the author.)

SAN JUAN POINT, 1920s. This secondary point once projected into Capistrano Bay south of the Dana Point promontory that marks the north end of Capistrano Bay. That was the natural anchorage for ships bringing supplies for Mission San Juan Capistrano, which lies three miles inland. It was the only shelter for ships between San Diego and San Pedro during 1800s hide-trading days. Capistrano Bay ends at San Mateo Point in south San Clemente.

SAN JUAN POINT, 1965. Small fishing and pleasure boats enjoyed limited protection within these coves before Dana Point Harbor was begun in the 1960s. Seen here through a break in the point of Fishermen’s Cove, which created an offshore stack, are the adjacent Dana Point headlands. San Juan Point was cut away during construction of the harbor. (Photograph by the author.)

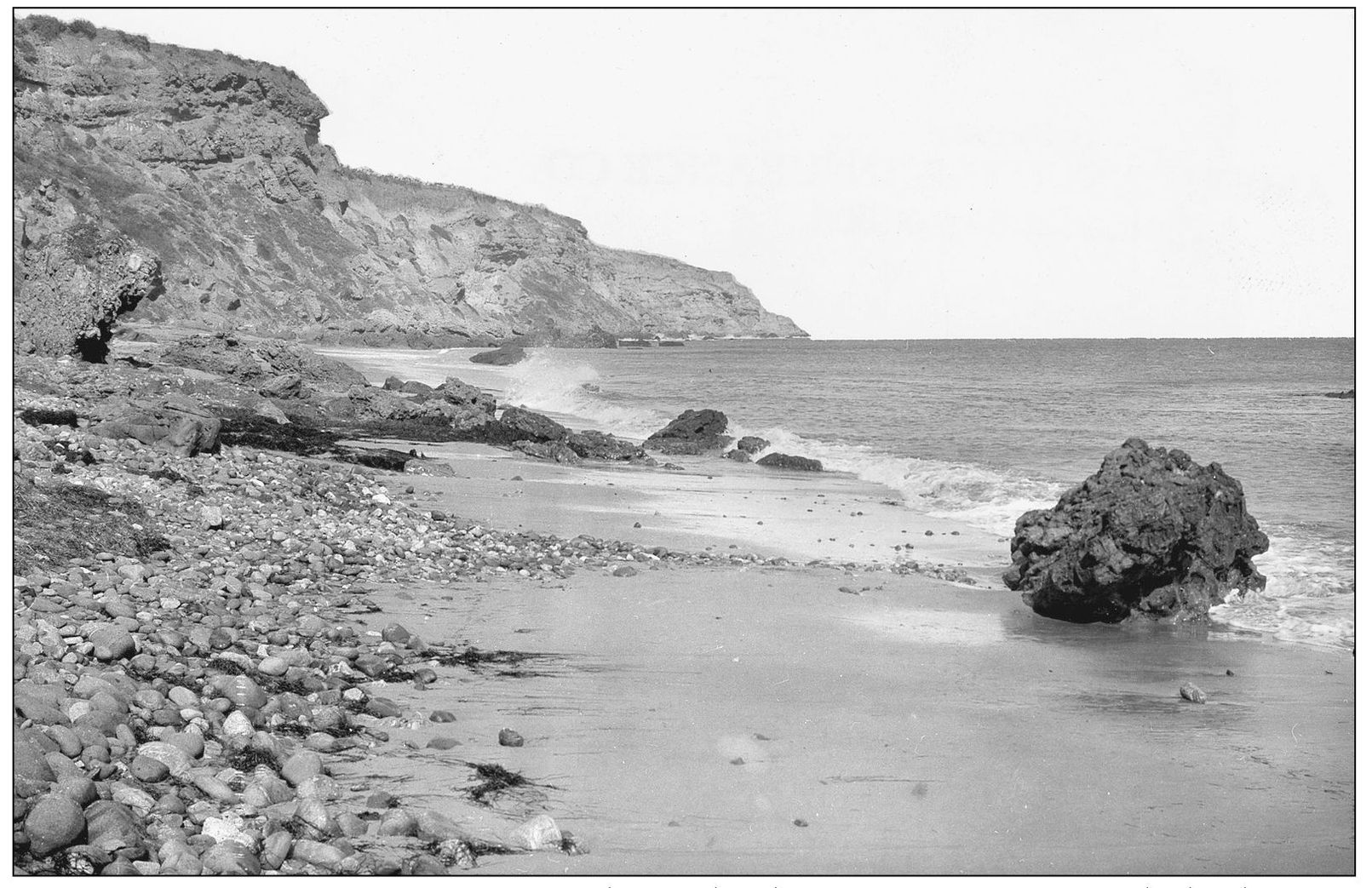

DANA COVE OUTGOING TIDE, 1880s. The north side of San Juan Point reveals the dramatic scene that would appear within Dana Cove as each ocean tide receded, revealing rocks alive with intertidal sea life from abalone and barnacles to starfish and urchins. Early wind-dependent ships had to anchor far from shore to avoid the rocky shoals.

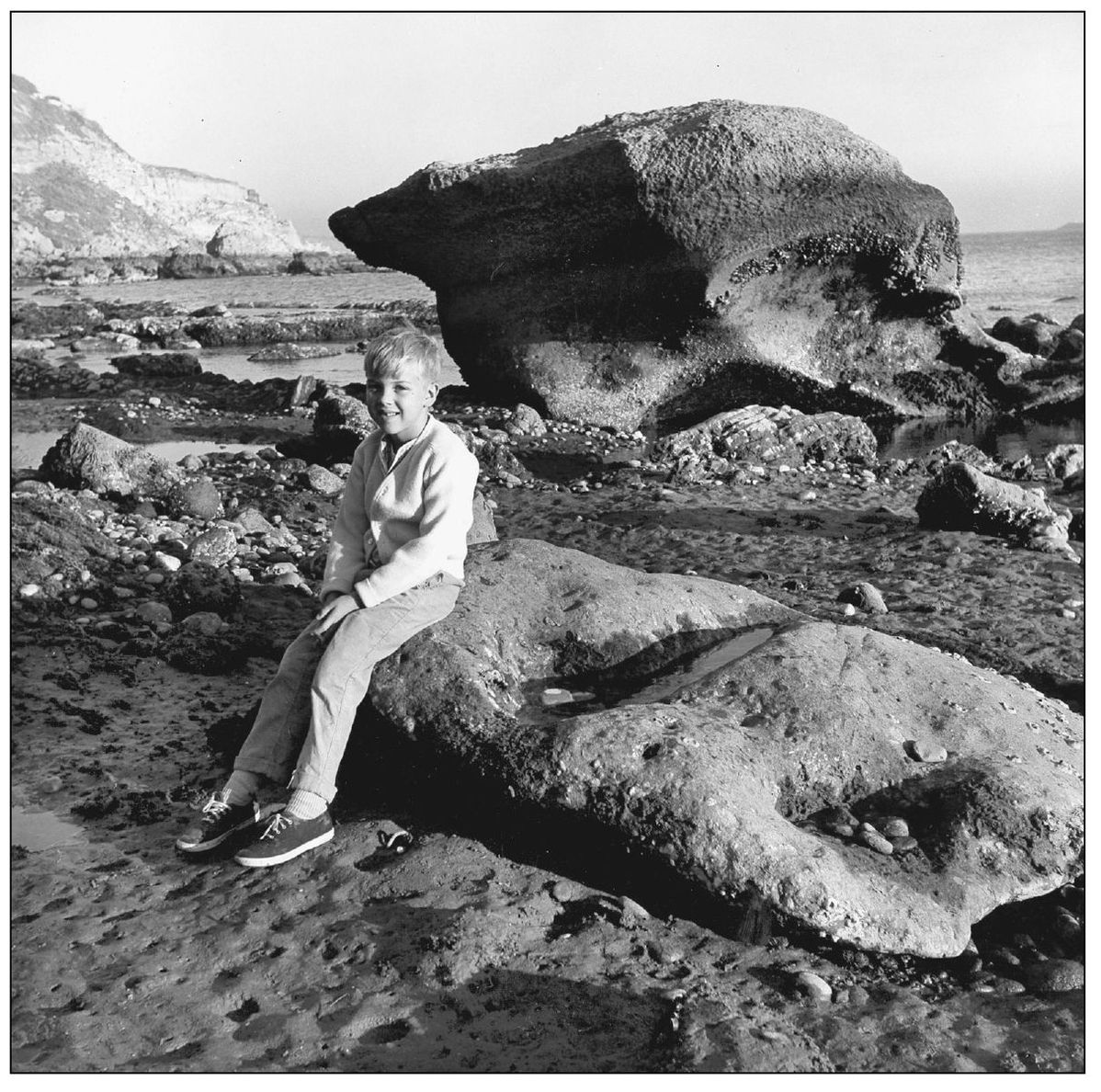

DANA COVE TIDEPOOLS, 1960s. This is the same scene within Dana Cove 80 years later at very low tide. The high-tide level can be seen near the top of the largest rock, far above the head of the author’s son, Brent Walker, who grew up in Dana Point. The exposed seascape is covered with signs of life. (Photograph by the author.)

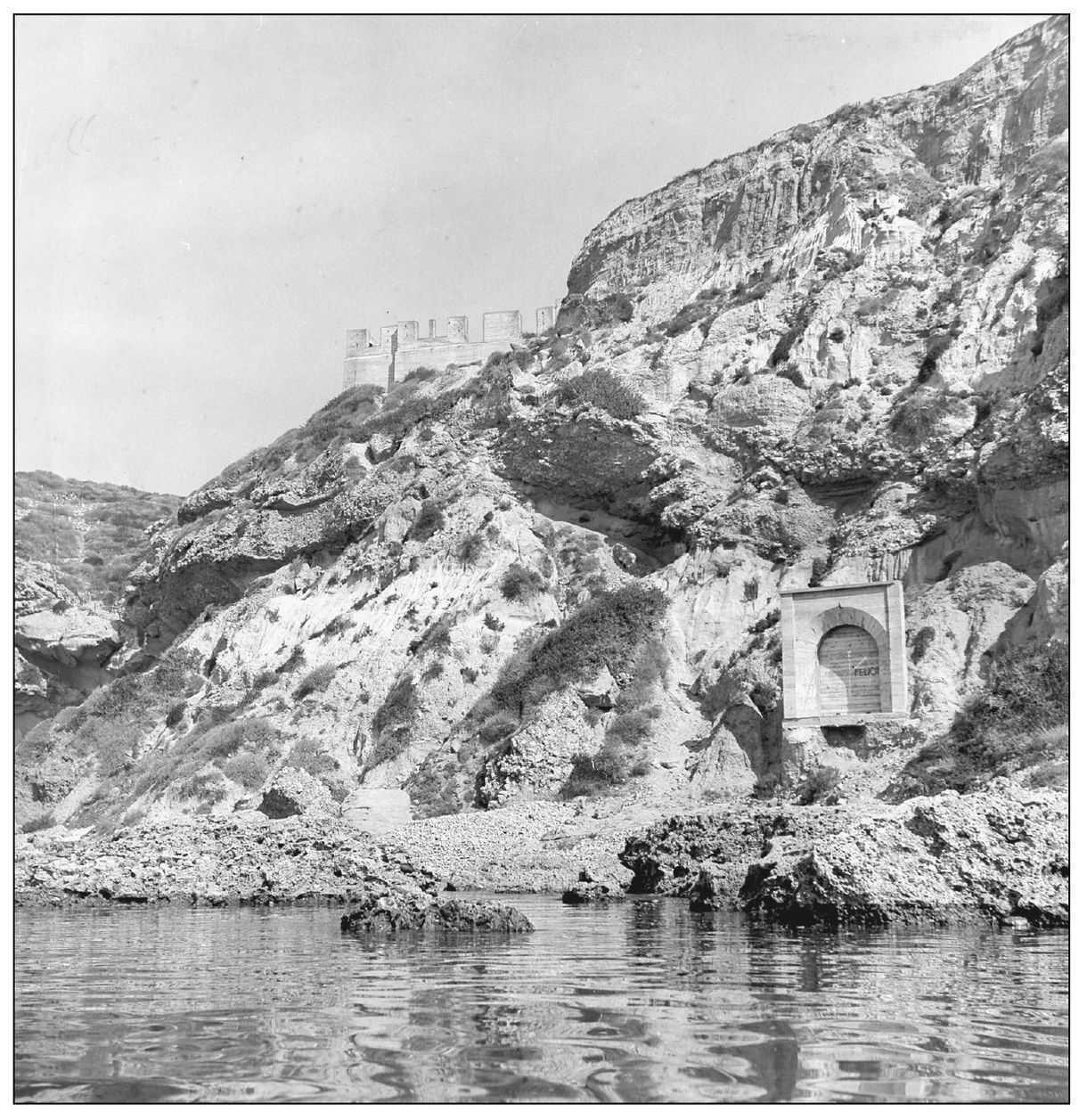

GHOST HOTEL. The focal point of an early bluff-top development was meant to be a large resort hotel. In 1930, the concrete superstructure of the Dana Inn was poured, visible at upper center of this 1960s photograph. The archway at lower right was to be the beach opening of an elevator rising to the hotel. The financial crash of 1929 stopped local construction. However, these two unfinished remnants became Dana Point landmarks. (Photograph by the author.)

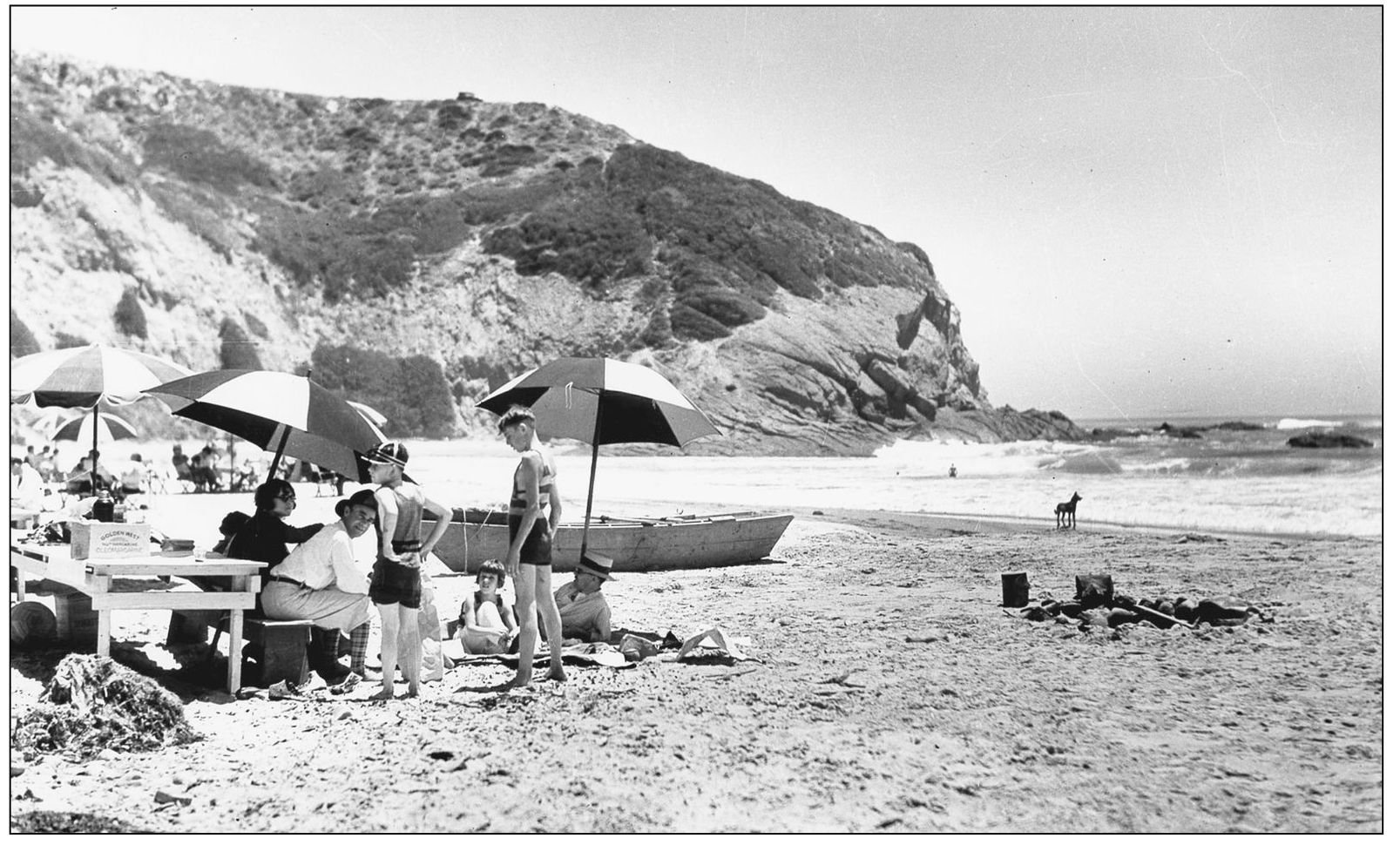

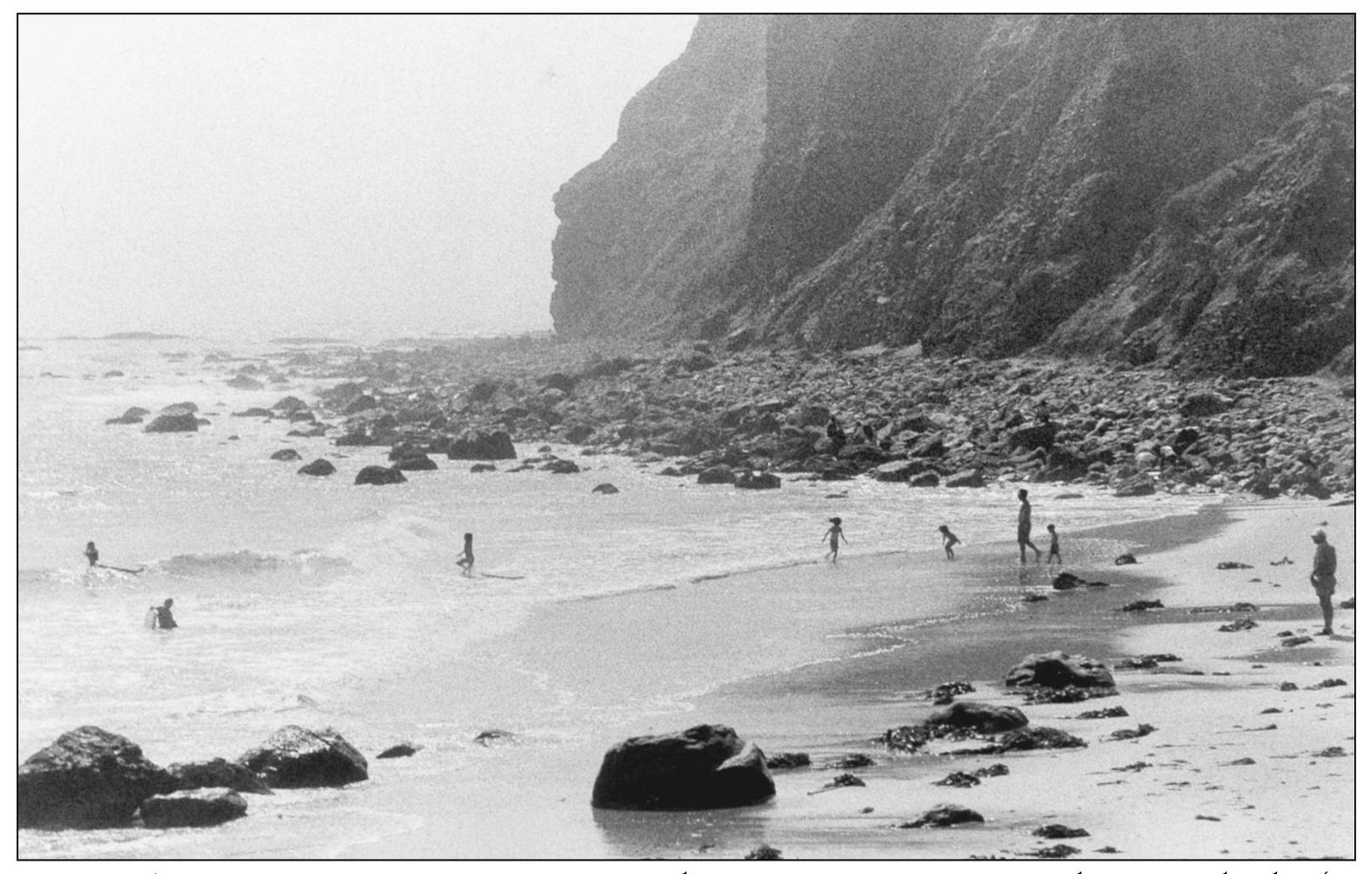

DANA STRAND, 1920s. The north side of the point shelters sandy Dana Strand Beach. It was the favorite swimming stop for visitors like these 1920s picnickers, with evidence of a beach barbecue. Rowboats could be launched there and dogs were allowed to roam the beach. This one was spending a pensive moment analyzing the surf.

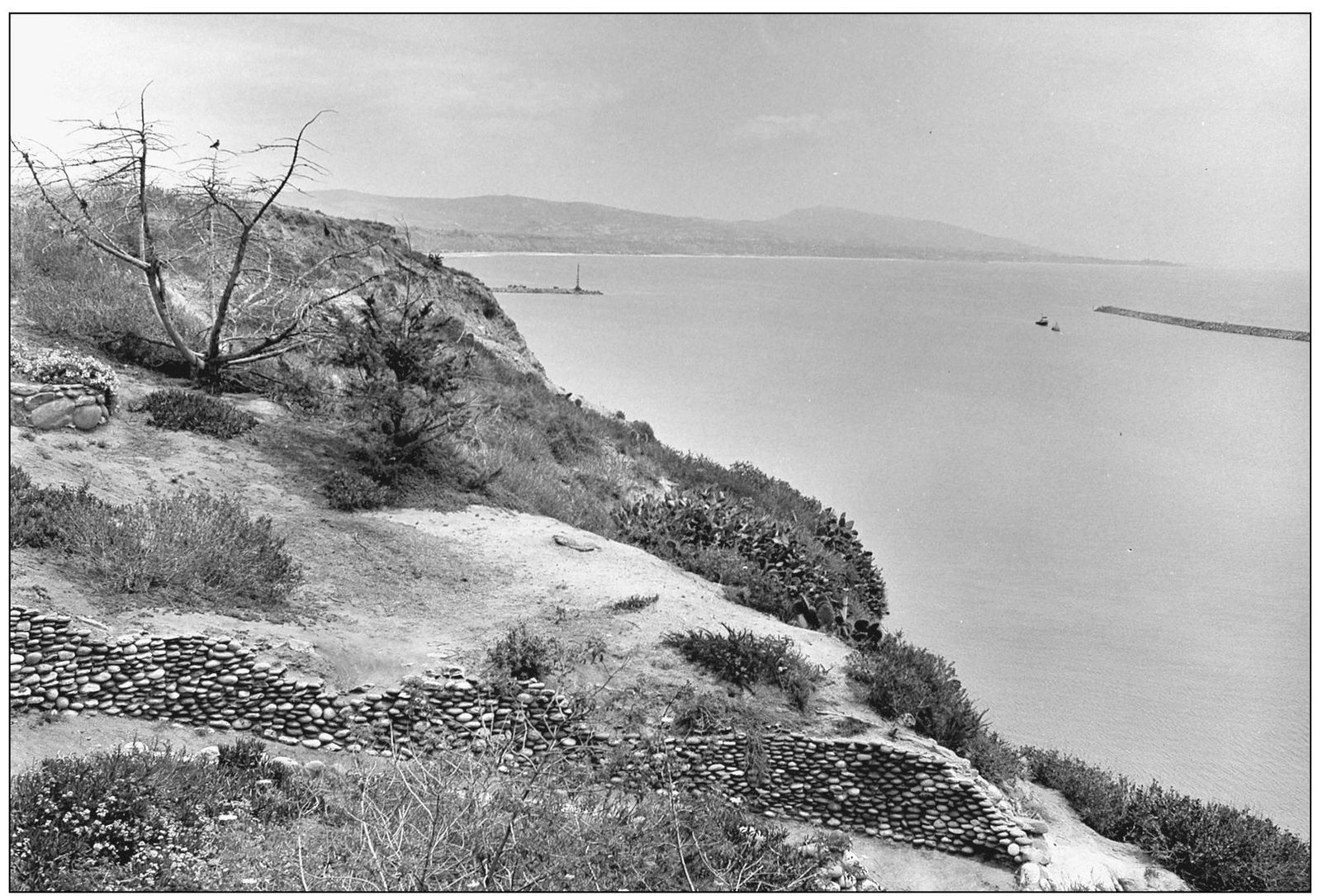

BREAKWATER BEGINS, 1966. The romantic bluffs and rocky shore would forever change with the construction of Dana Point Harbor. Here the east and west breakwaters grow toward each other. The curve of Capistrano Bay beyond leads to the Capistrano Beach portion of Dana Point and then to San Clemente. Remnants of a rock-lined stairway down the bluffs were still in place. (Photograph by the author.)

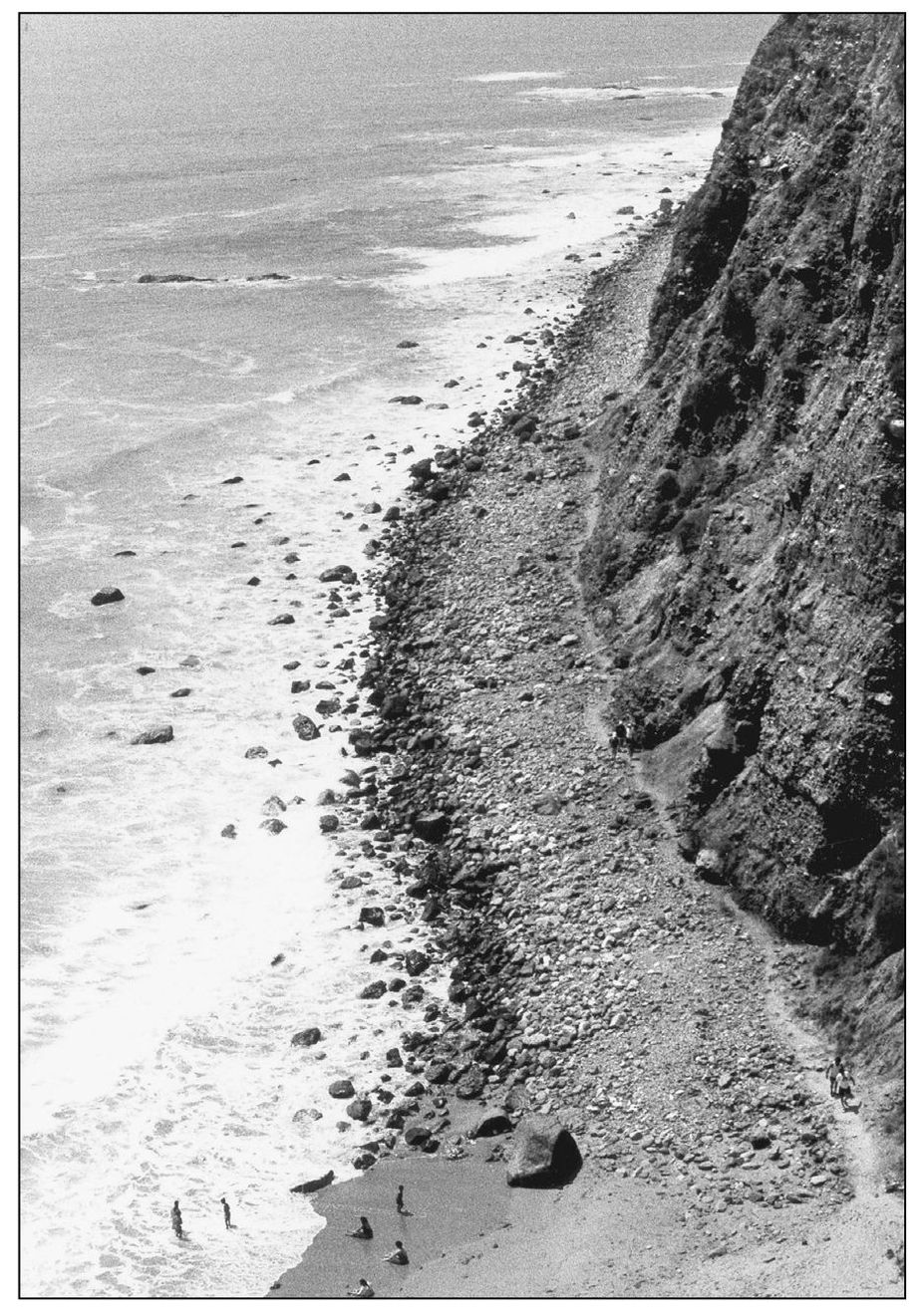

HEADLANDS TRAIL. At low tide, adventurous hikers can make their way around the face of the headlands from the marine preserve at its base. Their reward is the discovery of sea caves carved by waves into the bedrock said to contain unidentified bones. The caves were once thought to hold hidden pirate treasure, perhaps from the shipwrecked Spanish galleon known to lie offshore. (Photograph by the author.)

NATIVE AMERICAN PROFILE ROCK, 1960s. The Dana Point promontory has several sides (as seen in the book cover’s aerial photograph). One that slips into view from certain spots within the modern harbor is the dramatic profile of a Native American, chiseled by nature on the face of the rock. It watches for new arrivals by sea, guarding the ageless treasures of this natural setting. Local Native Americans no doubt used the promontory as a lookout point. (Photograph by the author.)

MONUMENTAL ROCK. Lying 300 yards offshore of Dana Cove, San Juan Rock attains monumental proportions at a very low or minus tide. Then it becomes a towering climbing wall for those who dare to reach the top, where there is an unbroken ocean view. Others, standing at its base, appreciate the sea-level mark that reaches above their heads. The harbor’s west jetty lies beyond in this 1980s view. (Photograph by the author.)