Nine

RESORT PORT CITY

We have an incredible site here in Dana Point. The wild ocean is on one side; the tranquil harbor is on the other, and the rugged cliffs form the backdrop. The inspiration for ongoing prime exploration is a constant challenge.

—Dr. Stanley Cummings Dedication of Orange County Marine Institute, 1981

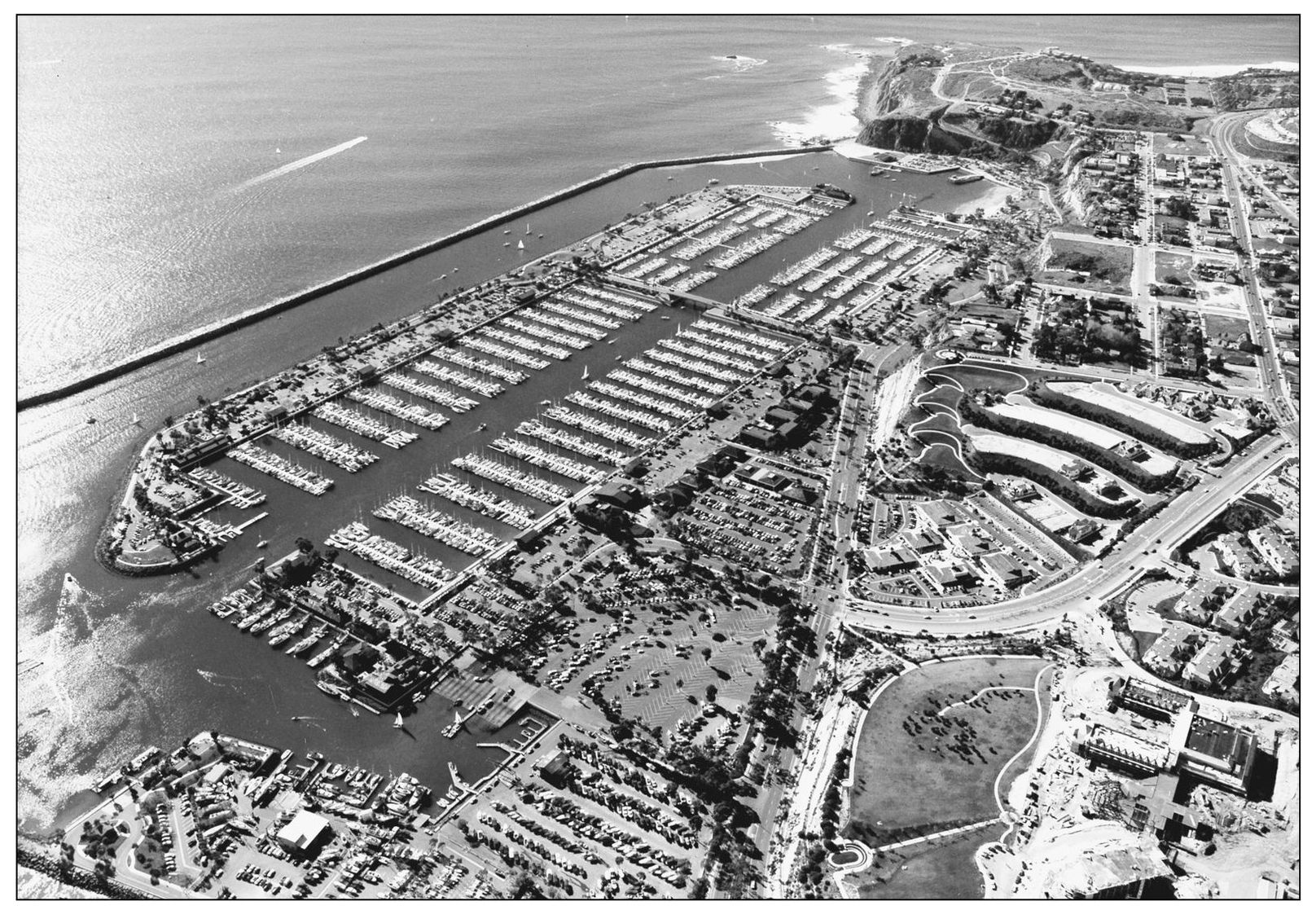

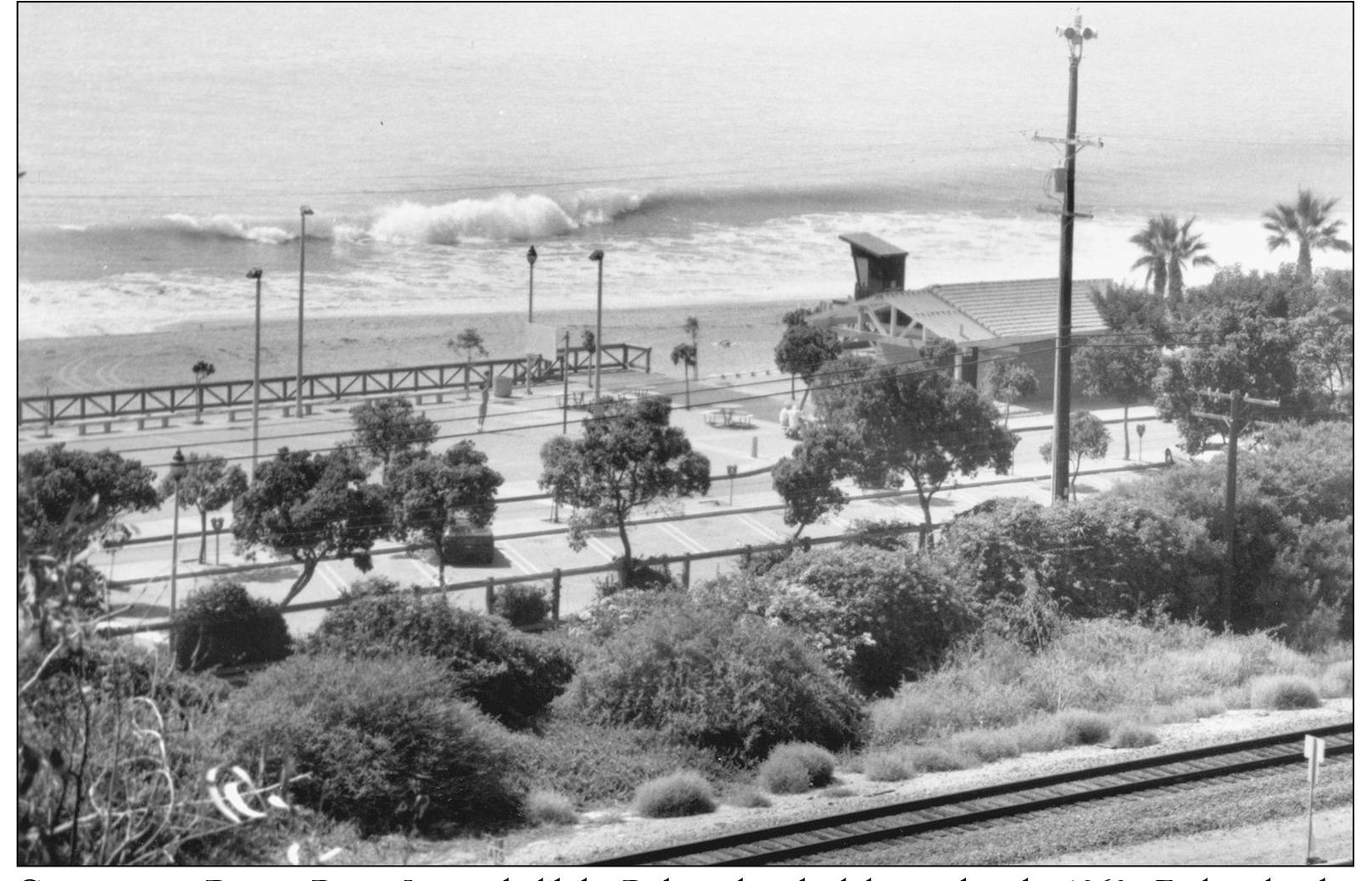

TWO-LEVEL RESORT PORT. This 1987 aerial view of Dana Point highlights the completed harbor and parks, with the Lantern Bay community underway and the Pavilion Center beside it. The headlands then remained an undeveloped mystery. In that year, the Dana Point Historical Society was founded with a goal of preserving the past as well as honoring current history. Incorporation of the city would follow in two years, unifying three communities. (Courtesy Lloyd de Mers.)

OCEAN INSTITUTE. In 1981, the then–Orange County Marine Institute moved into its permanent quarters in Dana Point Harbor. Since occupying these modest buildings, it has grown in scope and structure. Its location at the base of geologically significant Dana Point enhances its science teaching. At its back door is a protected marine preserve, and in its front yard are ships that enable its students to explore the sea itself. (Photograph by the author.)

LAND AND SEA ASSETS. In 1999, this educational entity was renamed the Ocean Institute, a private non-profit attended by students from throughout California and beyond. The mission statement is “to inspire all generations, through education, to become responsible stewards of our oceans.” In 2002, it moved into this more expansive education center. On land, students learn hands-on with interactive laboratories and exhibits. (Photograph by Cliff Wassmann.)

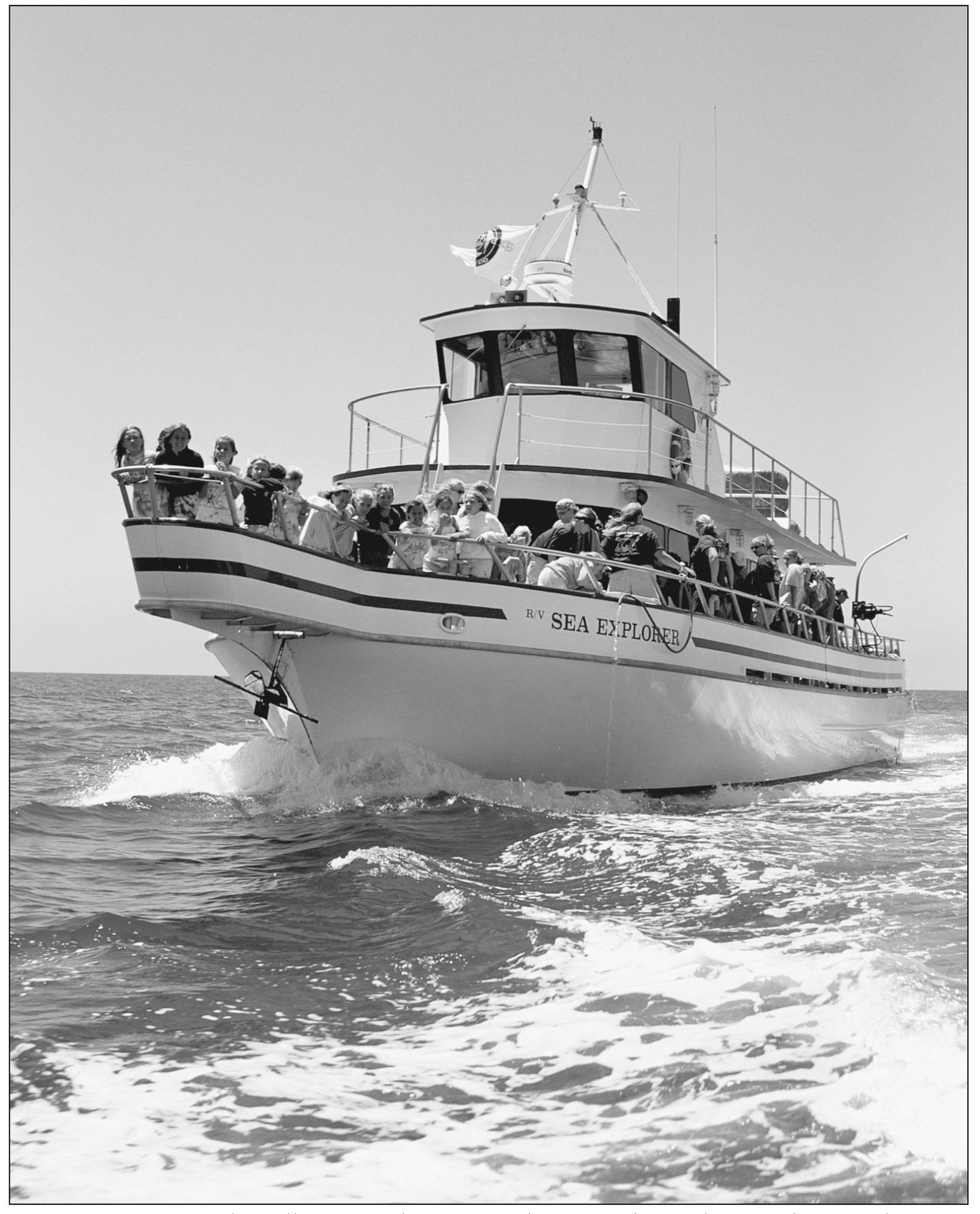

RV SEA EXPLORER. This fully equipped oceanographic research vessel offers educational cruises, including whalewatching, for students and the public. Since 1994, year-round classes have been conducted aboard the diesel-powered aluminum Sea Explorer with its custom oceanographic laboratory that provides students with a special opportunity for hands-on study of marine species they could never see on land or in aquaria. The Ocean Institute also has two tall sailing ships docked outside its state-of-the art complex. The Spirit of Dana Point takes older classes to sea for an introduction to serious sailing, while they also study marine life. The Pilgrim gives elementary school students the chance to learn the ropes of what sailing was like in the 1800s on overnight classes without leaving the harbor.

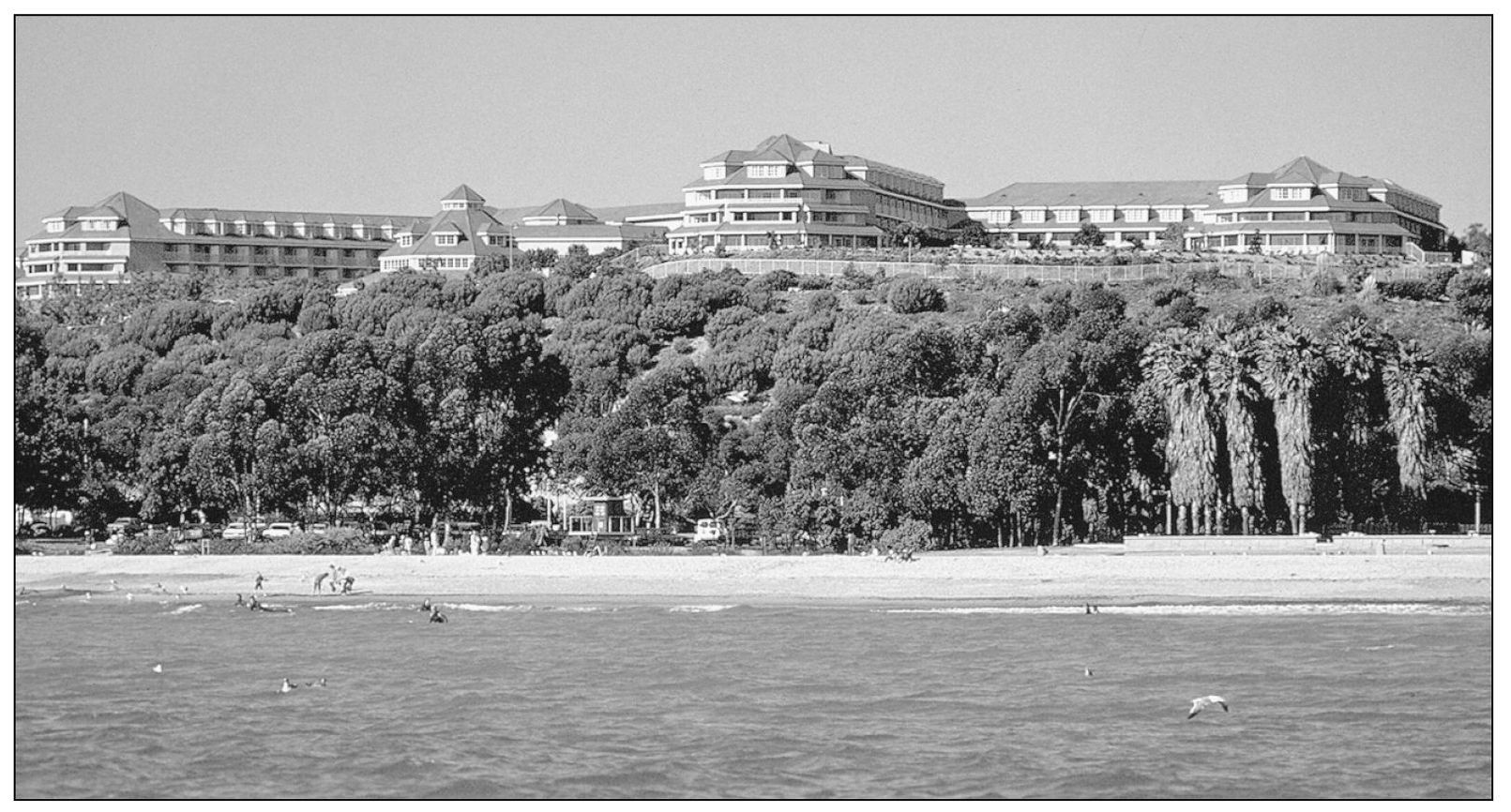

FIRST OF THE RESORTS. The Lantern Bay development of the 1980s included this 376-room Victorian-style hotel above Dana Point Harbor. It opened as the Dana Point Resort and later changed ownership to become the Laguna Cliffs Marriott Resort at Dana Point. It overlooks Lantern Bay Park with stairways connecting the upper city and the harbor. Highlights of the hotel include the Richard Henry Dana Ballroom, the Pacific Learning Center, and an on-site spa.

ST. REGIS RESORT. On 170 acres overlooking the coast is the 400-room St. Regis Monarch Beach Resort and Spa. Its Tuscan-style architecture carries a feeling of the Italian Riviera, and its grounds include the Monarch Beach Golf Links with an oceanfront green. Its guests enjoy a blend of comfort and top technology. Resort amenities of Dana Point headlands development are yet to come to join these top-rated luxury oases within Dana Point, the new resort port.

RITZ-CARLTON. Echoing the Spanish architecture of Dana Point’s unfinished dream hotel of 1930 on a nearby bluff, this elegant resort has been a significant part of Dana Point social life since the 1980s, though its name is officially the Ritz-Carlton Laguna Niguel. This harkens back to pre-incorporation days, when Monarch Beach was considered part of Laguna Niguel. This 393-room Ritz-Carlton has been ranked consistently among the top resorts in the world.

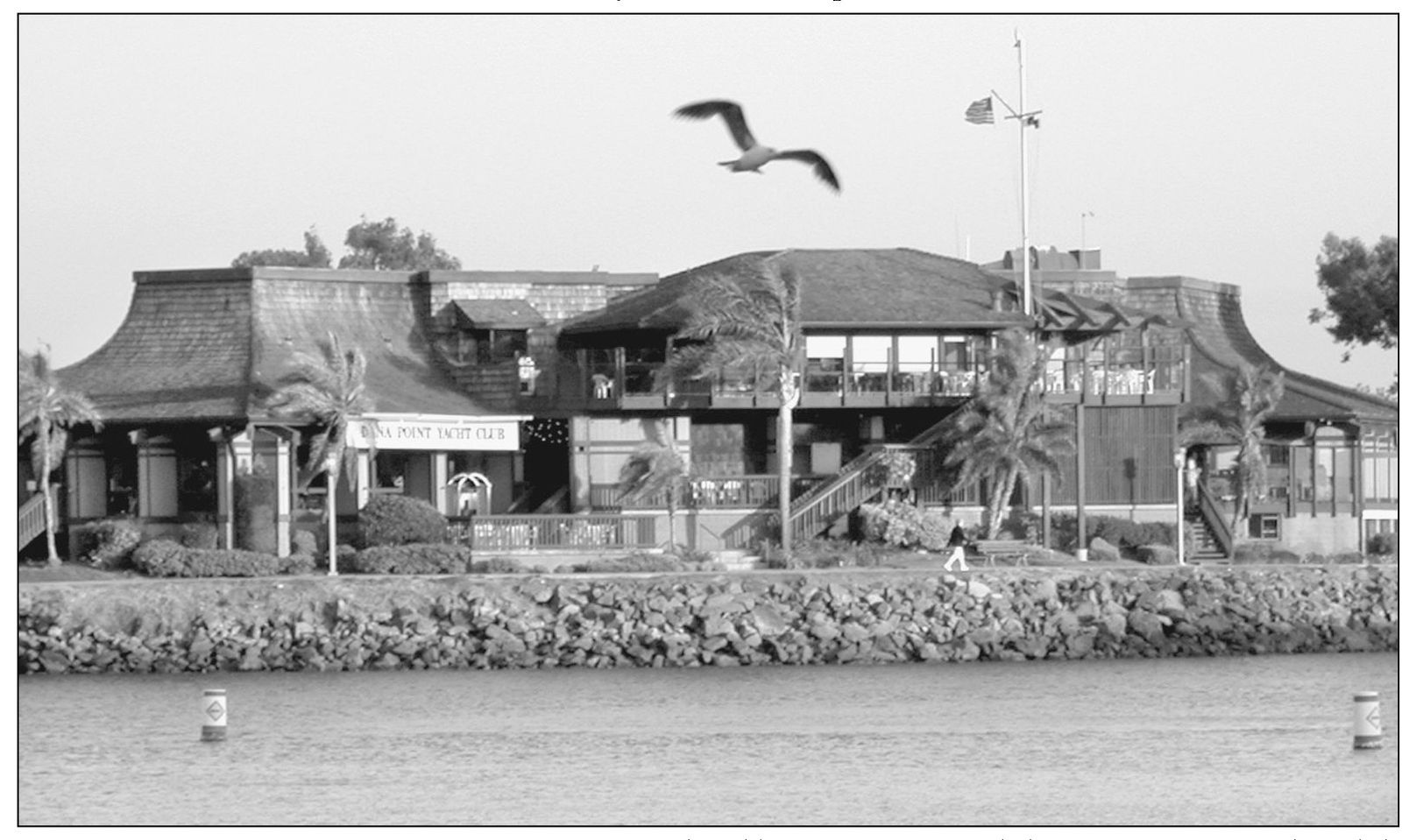

DANA POINT YACHT CLUB. A group of foresighted boaters organized the Dana Point Yacht Club in 1952 without a clubhouse or a harbor. In the year following completion of the harbor, 1972, the expanded membership opened a clubhouse there. In 1998, they moved to this site on Dana Island. There the club began its annual Richard Henry Dana Charity Regatta, adding to the romance of local history. Dana West Yacht Club has also been active in the harbor since 1986.

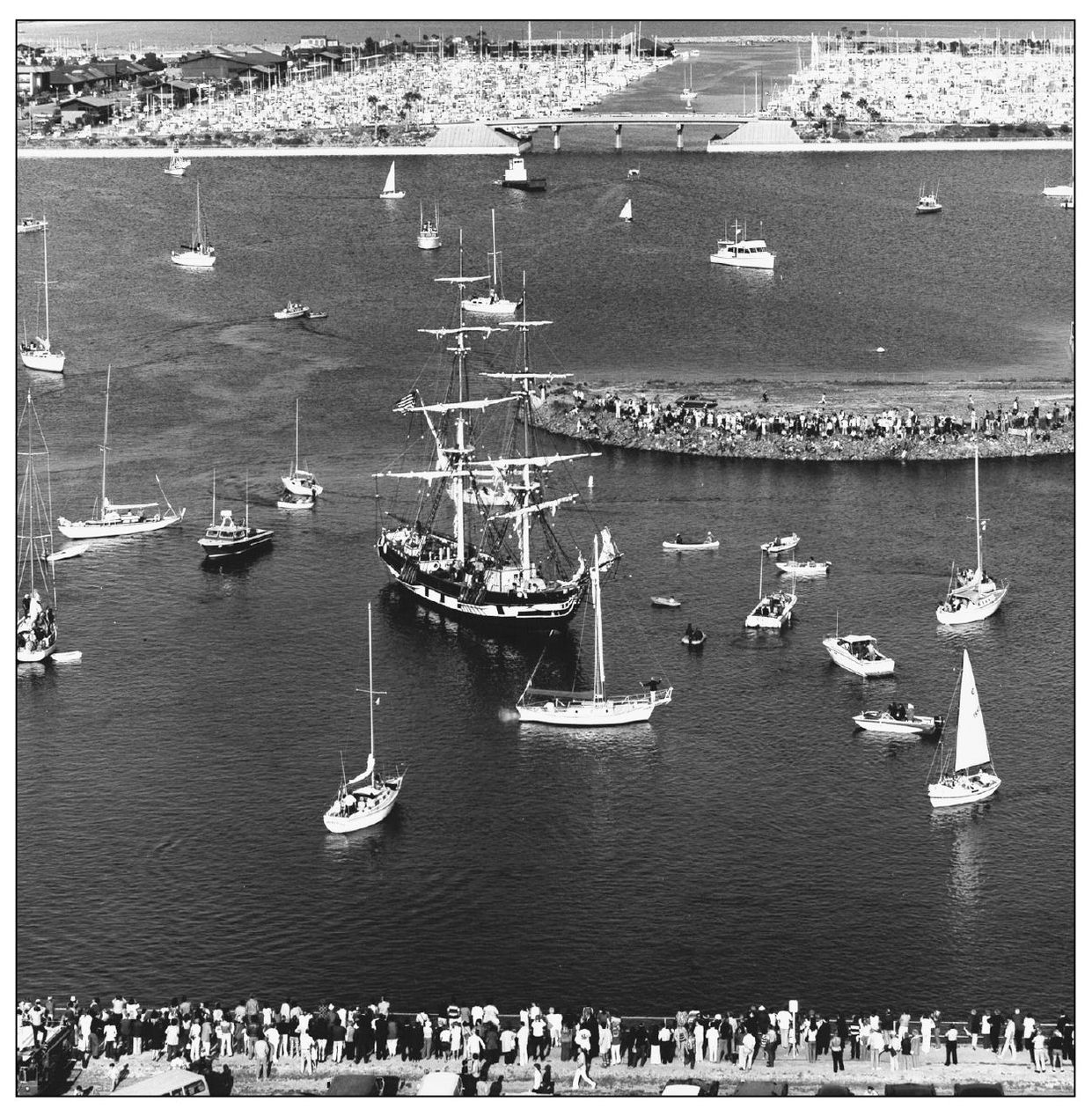

TALL SHIPS FESTIVAL. Dana Point was meant to honor tall sailing ships and now welcomes their participation in its celebratory Tall Ships Festival each fall. Crowds gather to view and tour the elegant wind-powered fleet from the past. It all started in 1975, when this re-creation of Dana’s ship Pilgrim made its first call on this port. As the photograph hints, she drew a crowd of 15,000 on an ordinary workday, visitors from afar reveling in the beauty of the past.

SPIRIT OF DANA POINT. Enjoyment of tall ships is a year-round adventure for Dana Pointers, since two of the storied ones call it their home port. Joining Pilgrim at its Ocean Institute docks is the Spirit of Dana Point, a topsail schooner and replica of a speedy 1770s privateer. She is the institute’s at-sea learning classroom for marine science and living history as well as a public cruise ship offering a variety of sails. (Photograph by Cliff Wassmann.)

LEARNING THE ROPES. In addition to teaching young students the ardors and glories of crewing a vintage rigged ship, the Ocean Institute extends this slice of living history to the devoted volunteer crew that maintains the ships, with headquarters in a New England–style sail loft beside the dock. Pilgrim sails only once a year, her 8,600 square feet of sails unfurled. Her two tall masts rise 110 feet in the air, scaled by experienced crews in the line of duty. (Photograph by the author.)

NEW ENGLAND REAPPEARS. While equipped with legally required engines, a stainless steel sink, and crew bunks for student overnights, this Pilgrim re-creation imparts a true feeling of being a player in maritime history. Elementary school students become crewmates, assigned to such duties as handling lines, raising sails, keeping watch, and gathering hides, as in the past. It is a rugged adventure, but one they never forget. (Photograph by the author.)

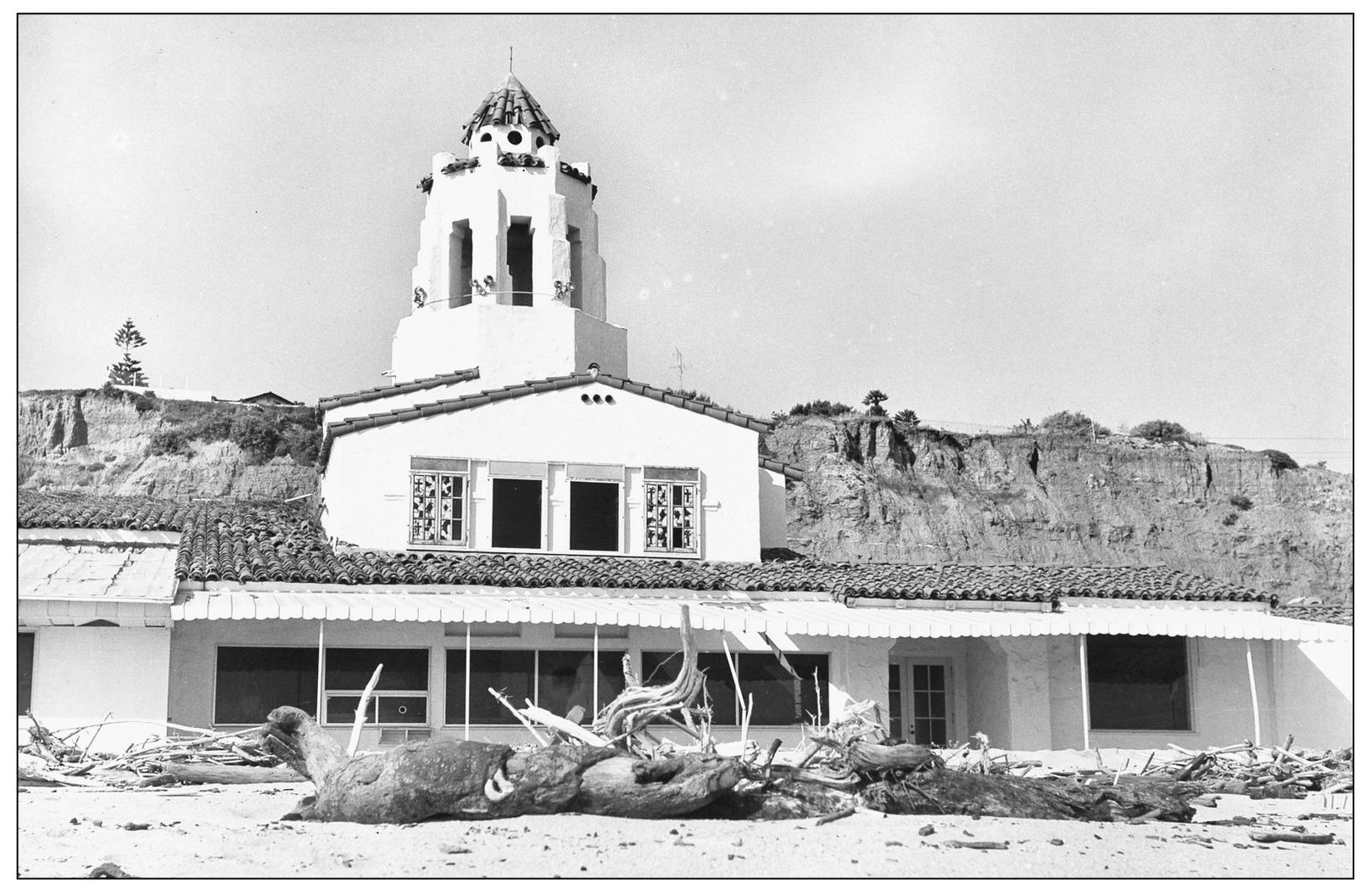

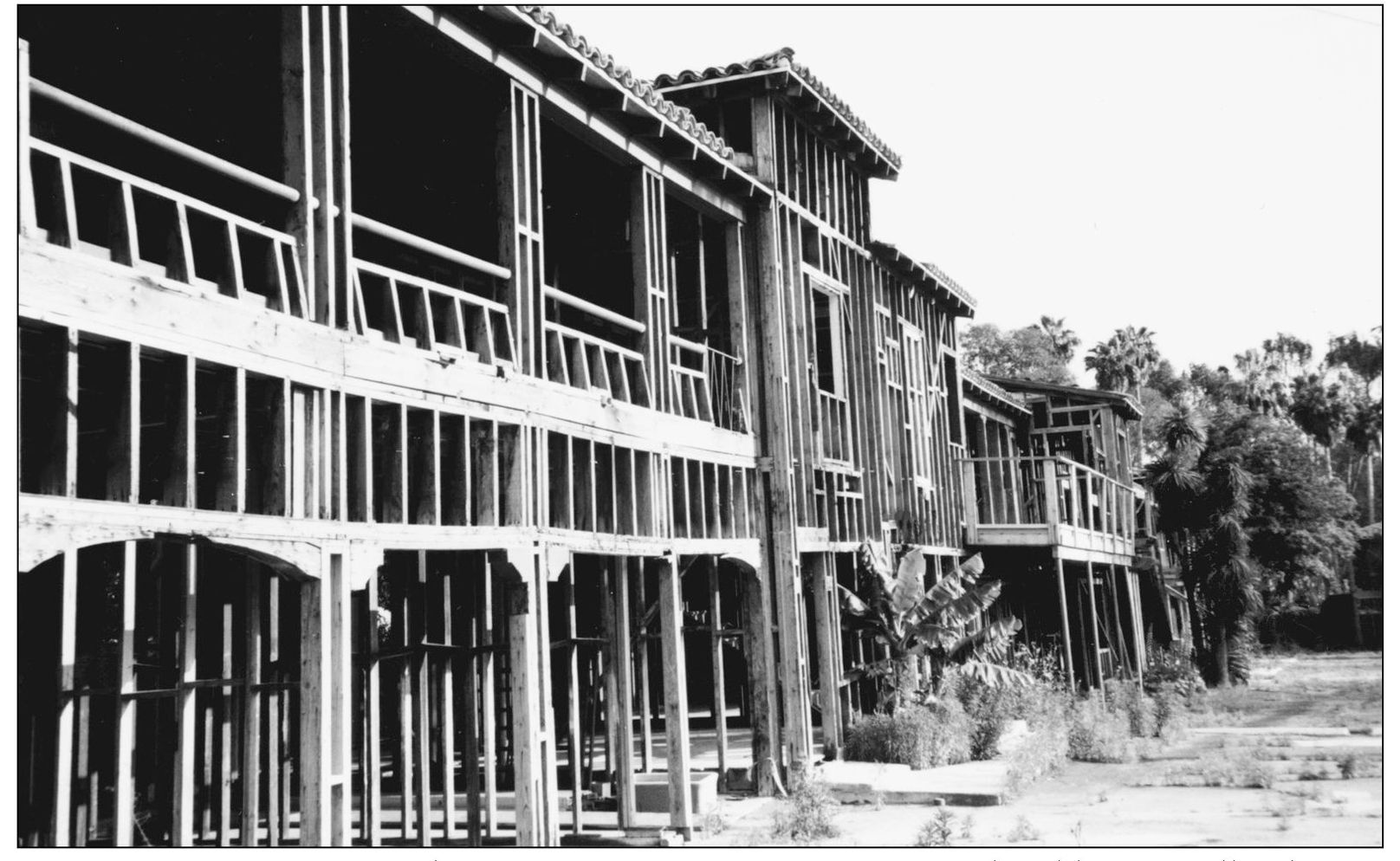

SOME 1920s LANDMARKS LOST. The Capistrano Beach Club’s strand suffered serious erosion, and driftwood from storms replaced the sand. After its final closing in 1966, it also suffered from vandals. A development company won approval to replace it with a 10-story hotel. Enraged residents filed suit. Nonetheless, the new owners razed the lovely landmark from its tower to its toes. The hotel to replace it was never built. (Photograph by the author.)

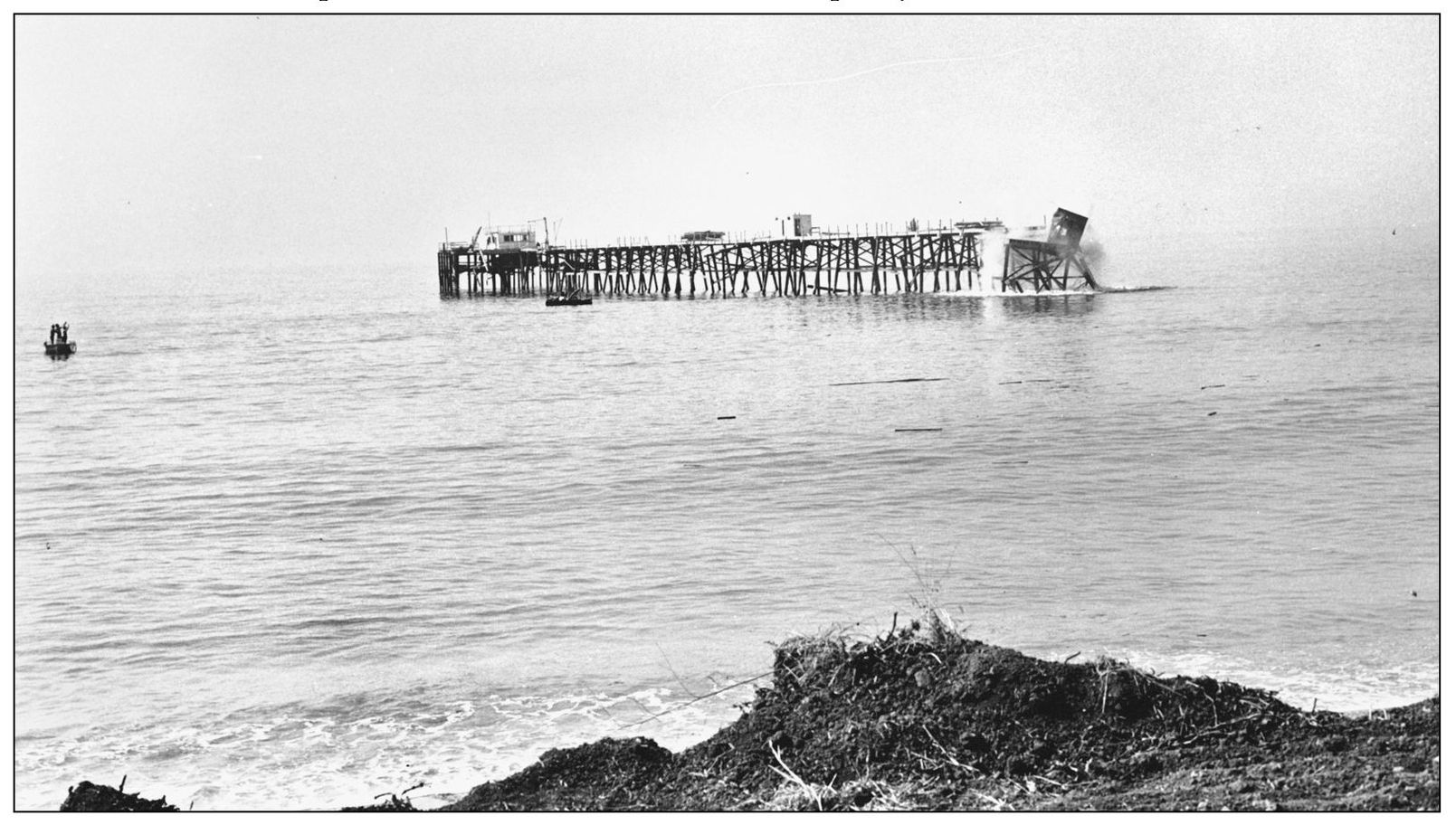

CAPISTRANO BEACH FISHING PIER. This living remnant of Ned Doheny’s 1920s plan served fishermen and sportfishing boats for four more decades. Finally, storms in 1964 broke it from the land and left it shortchanged and irreparable. It had to be dynamited away, after flocks of pigeons living within it were rescued. The demolition team carefully carried them out alive in the empty explosives boxes.

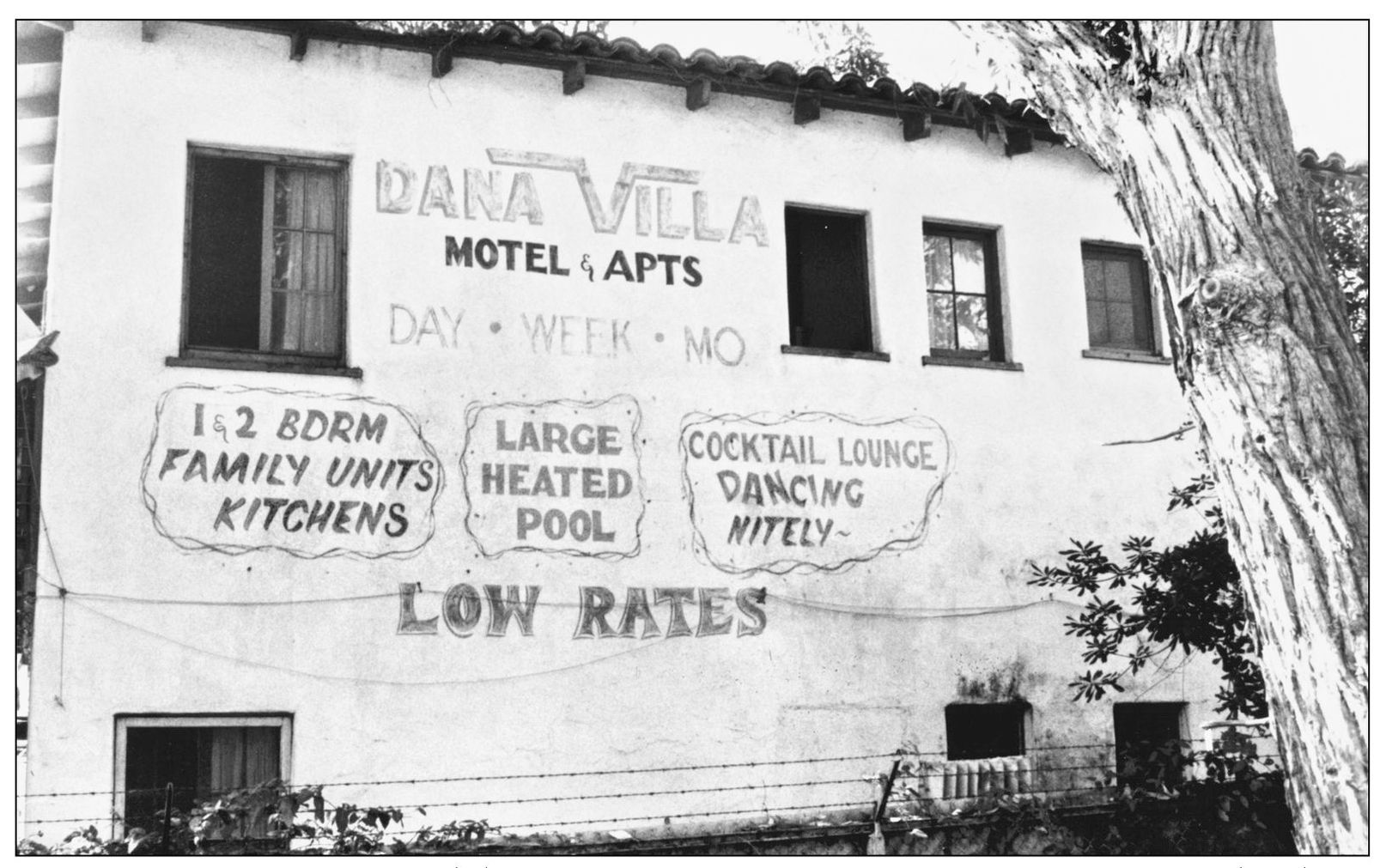

DANA VILLA’S LAST CALL. While Dana Point was growing into a resort port, its first hotel was ailing. The Dana Villa Motel and Apartments advertised low rates for “family units,” and its cocktail lounge advertised “dancing nitely.” It still had a “large heated pool” and “low rates,” but the handwriting was literally on the wall. (Photograph by the author.)

TENDER 1920s TIMBERS. There were vain attempts to resurrect the old Dana Villa, then to turn its grounds into a new version worthy of its location at the harbor’s south entrance. Finally the city decided it should be demolished; it was in 2001. The large bare lot on the highway next to Doheny State Beach supports seasonal endeavors such as Christmas tree sales, with no final blueprint yet in sight. (Photograph by the author.)

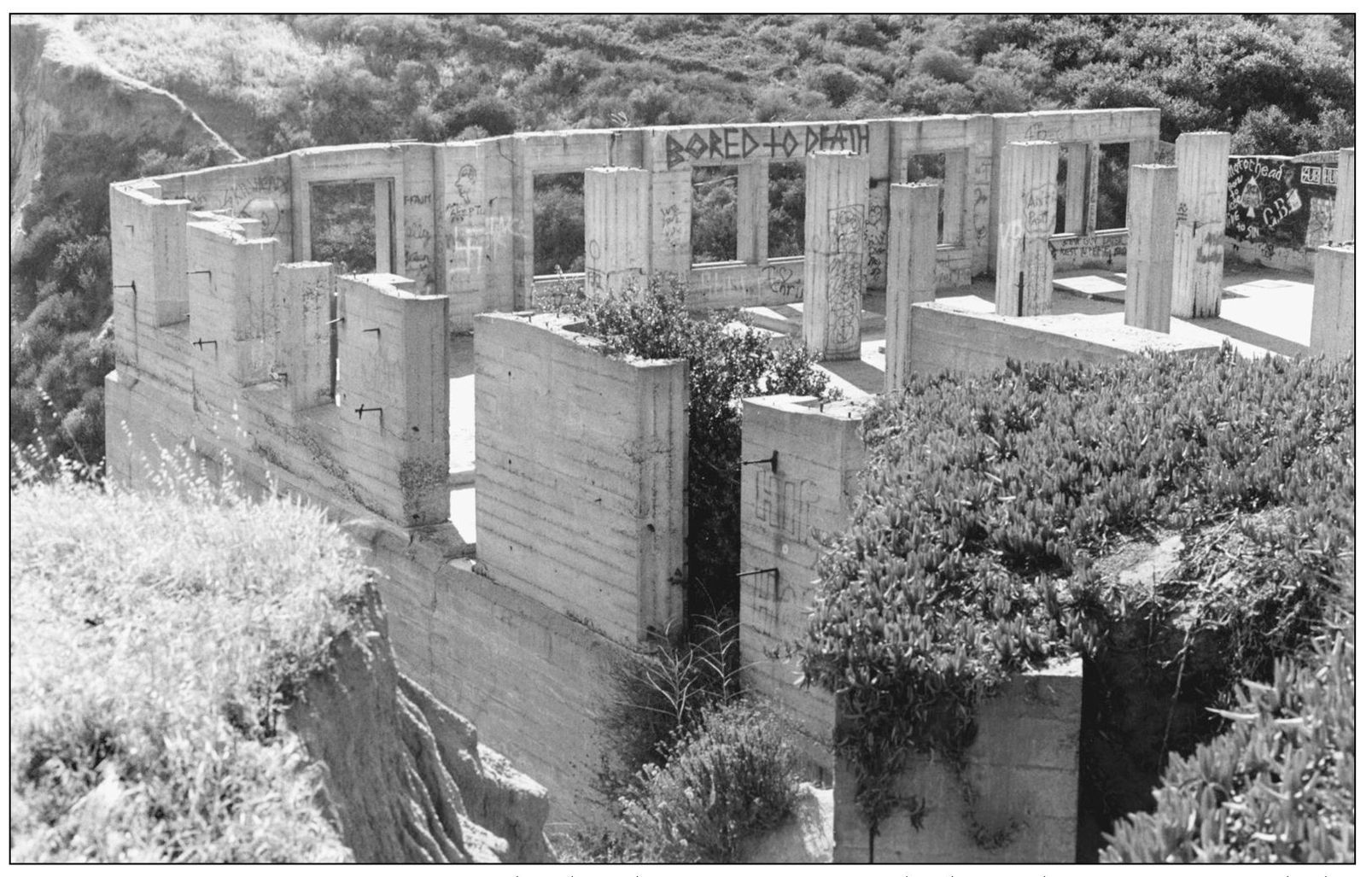

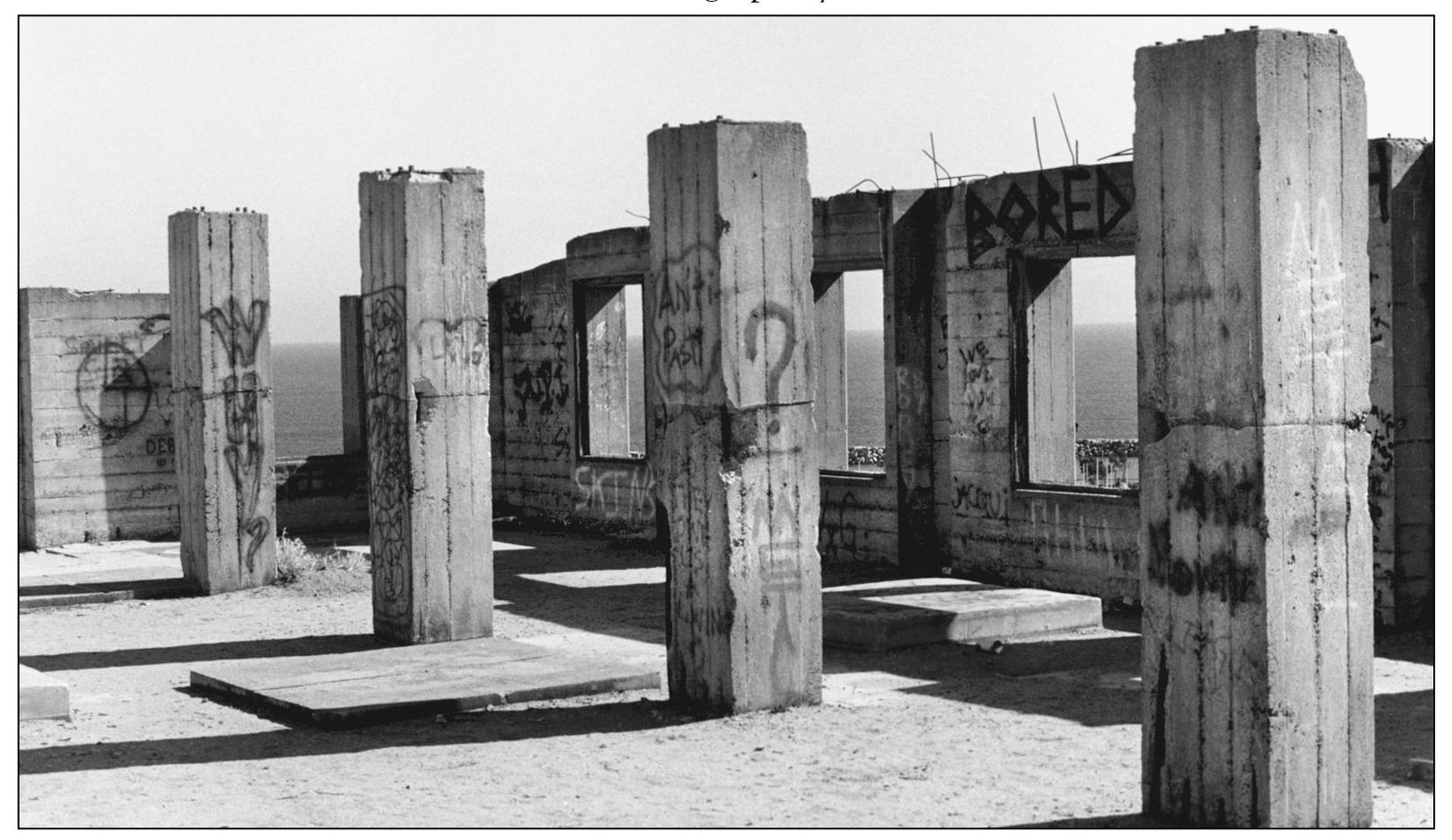

LINGERING GHOST HOTEL. Over the decades since its unfinished foundation was poured, the old Dana Inn watched the development of Dana Point Harbor and the city’s resort amenities, realizing it had been destined to be one of them. Its framing gone, its windows closed, it dominated Dana Point’s bluff-top silhouette. Cliff climbers and birds of prey found it an inviting rest point. Vandals made their unwelcome marks. (Photograph by the author.)

FATE: A QUESTION MARK. The sturdy concrete ruin seemed impervious to change—a mysterious Stonehenge adding curiosity to the site. Public pressure required its owner to demolish parts and mortar up others in the 1960s. A chain-link barbed-wire fence kept out the curious. Legends arose about weird wails and ghostly apparitions. A graffiti question mark was apropos. (Photograph by the author.)

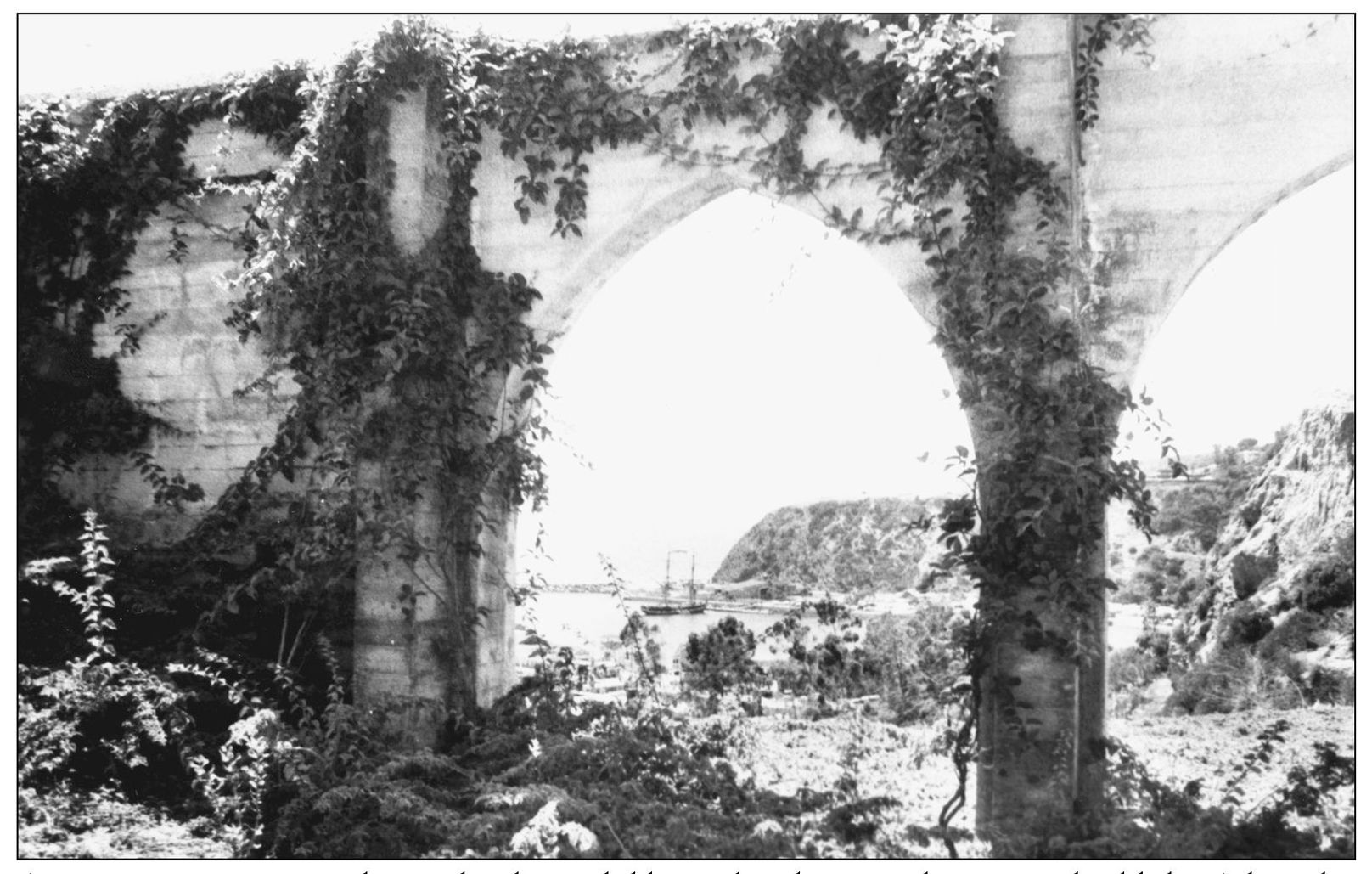

ARCHES PRESERVED. When a developer did begin breaking up the ruin to build the Admiralty complex in the 1980s, the new Dana Point Historical Society stepped in to salvage a remnant. One row of original arches was preserved, now a focal point on a bluff-side trail between Streets of the Violet and Amber Lanterns, where traces of the 1920s stone path can still be seen. Here the Pilgrim and the headlands appear through one arch. (Photograph by the author.)

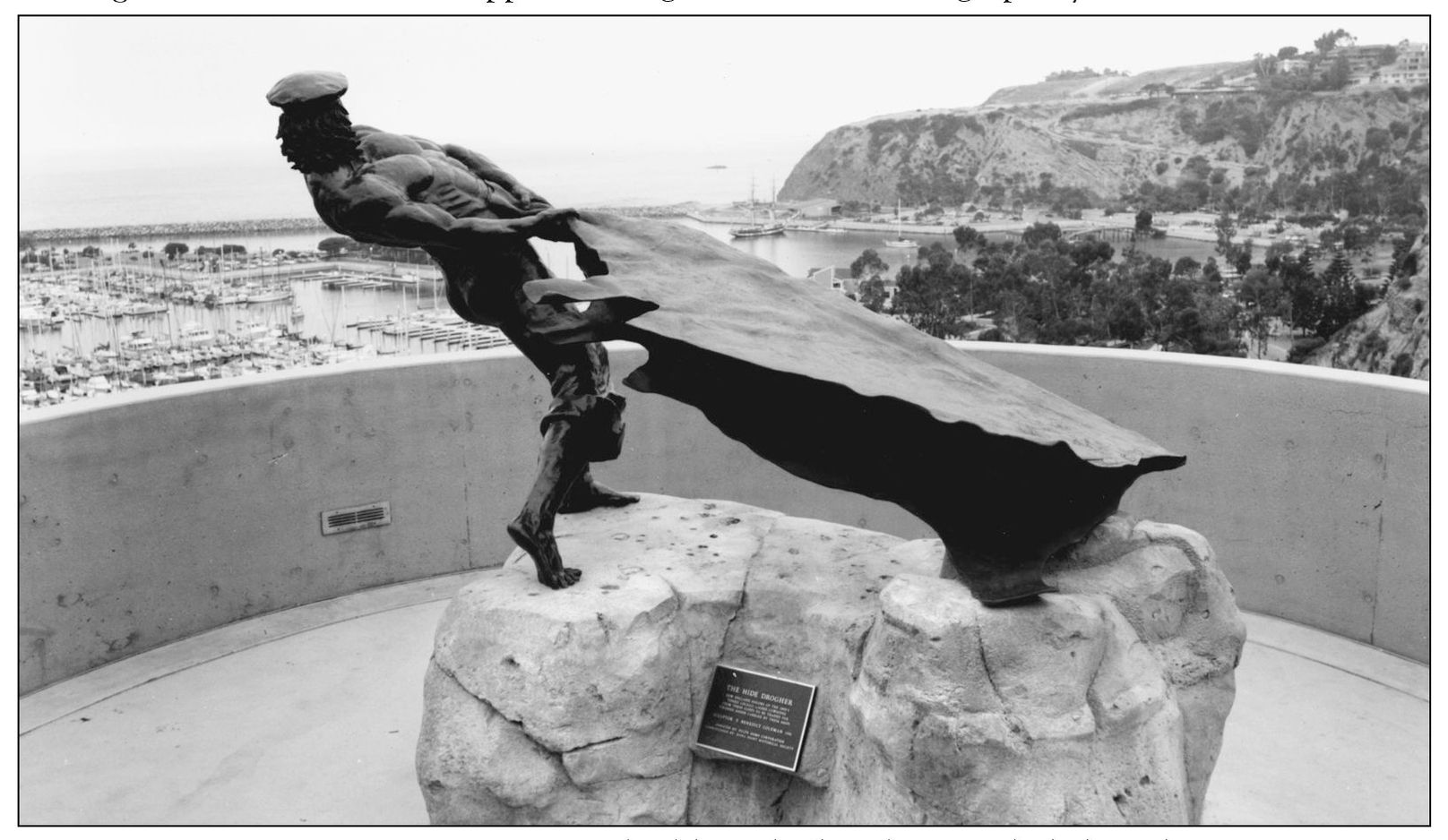

HIDE DROGHER STATUE. Permission to build on the hotel site included funding a piece of art. A statue of one of Dana’s crewmates tossing a cowhide over the bluff, as in history, was designed. Liz Bamattre, historical society president, became the adoptive mother of the Hide Drogher, guiding details of its creation and installation. The Drogher also became the society’s logo: a worker whose job was to deliver the goods to his crewmates, an Old West Indies term.

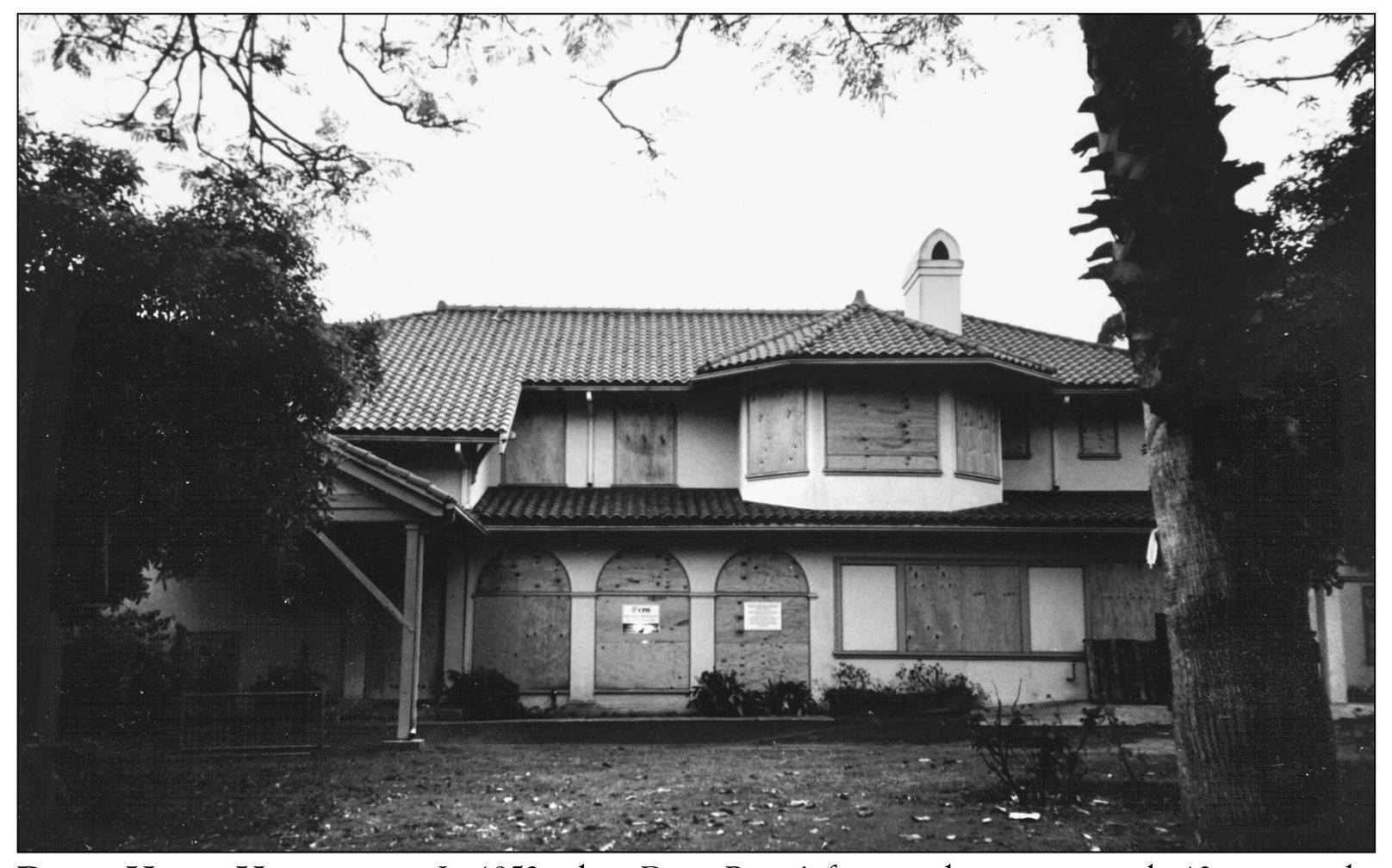

DOLPH HOUSE HIBERNATES. In 1953, when Dana Point’s first residence was nearly 40, it earned a new role as an office for Capistrano by the Sea Hospital. Modern buildings were erected around it. This “hospital of tomorrow” had celebrities among its patients and became a university teaching hospital. After it closed in 1998, the buildings were vandalized. The Dolphin was boarded up, its future questionable. (Photograph by the author.)

NEW LIFE FOR AN OLD HOUSE. In the new century, the property was acquired for construction of a group of select homes on the secluded hilltop. Thankfully, the Dolph House was not only saved, but was beautifully restored throughout and given state-of-the-art residential amenities after having been “the old building” in its hospital days. Now it shines as an elegant private residence again with a unique history.

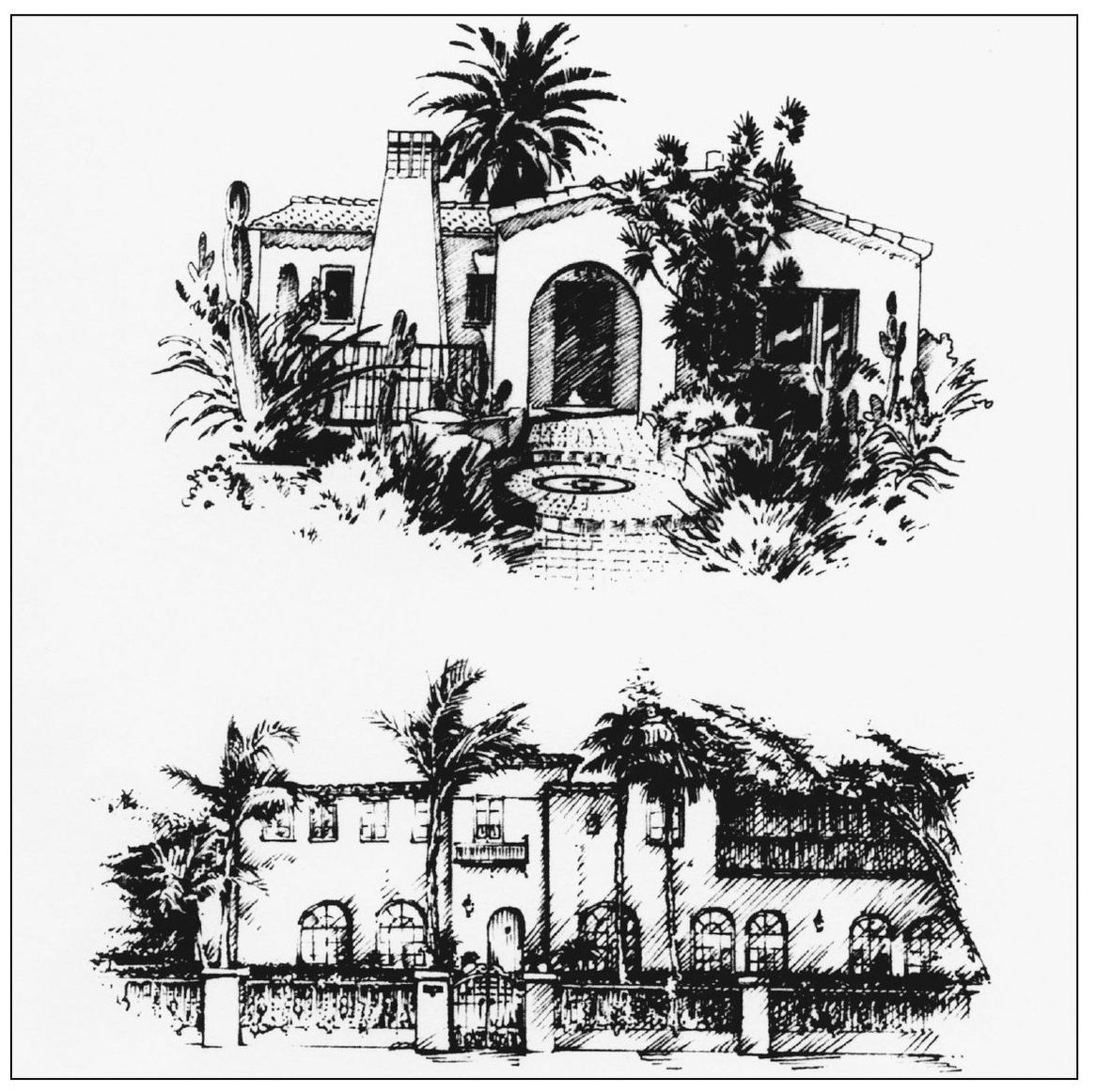

DANA POINT HOME TOURS. In 2000, the Dana Point Historical Society initiated a new phase of its historical restoration commitment by inviting the public to tour significant Dana Point homes. Its overwhelming success has made the Home Tour an annual event, featuring residences including 1920s Woodruff (above) and Doheny (below) homes and 1960s models in Monarch Bay. In the process, the historical society has aroused interest and affection for buildings of the local past.

FIRING UP HISTORY. When the Stonehill Bridge was completed in 1992, the first vehicle over it was this 1965 Crown fire engine, the first state-of-the-art unit to serve the area. It spent its whole career at Station 29 in Capistrano Beach, acquired by the Dana Point Historical Society when it retired. Celebrating this dual role of history and civics are, from left to right, Doris Walker, historical society and Festival of Whales cofounder; Bill Bamattre, the mayor who drove the fire truck that day; and Carlos Olvera, then and now society president.

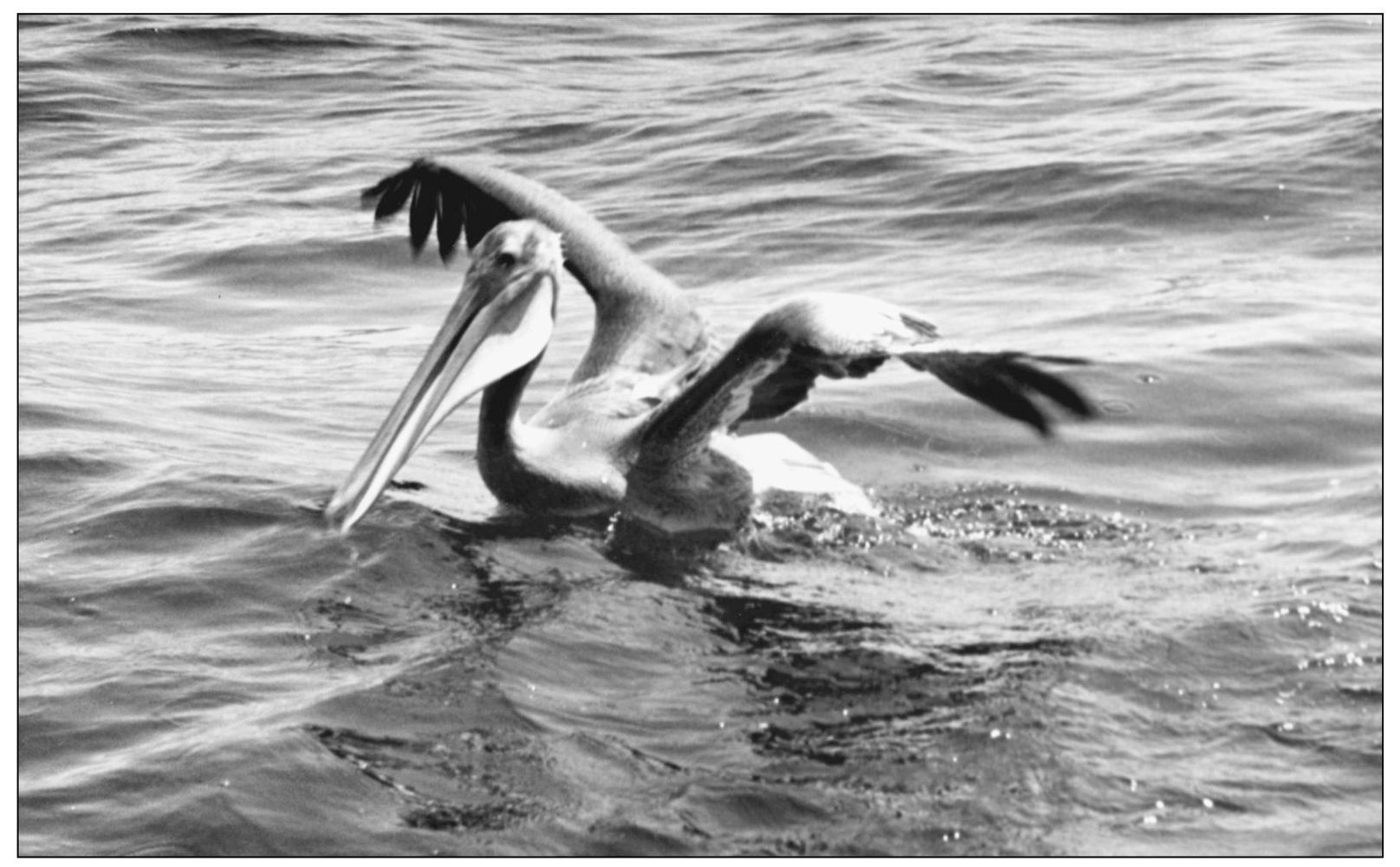

DANA’S FEATHERED FISHERMEN. Pelican watching is a special sport within Dana Point Harbor. Diving and soaring in search of fish, brown pelicans are the most historic of species along this coast, little changed since their prehistoric days and celebrating a triumphant return from endangerment. They hang out on the bait barge and breakwaters and greet each returning sportfishing boat, knowing what it has carried back to the dock. (Photograph by the author.)

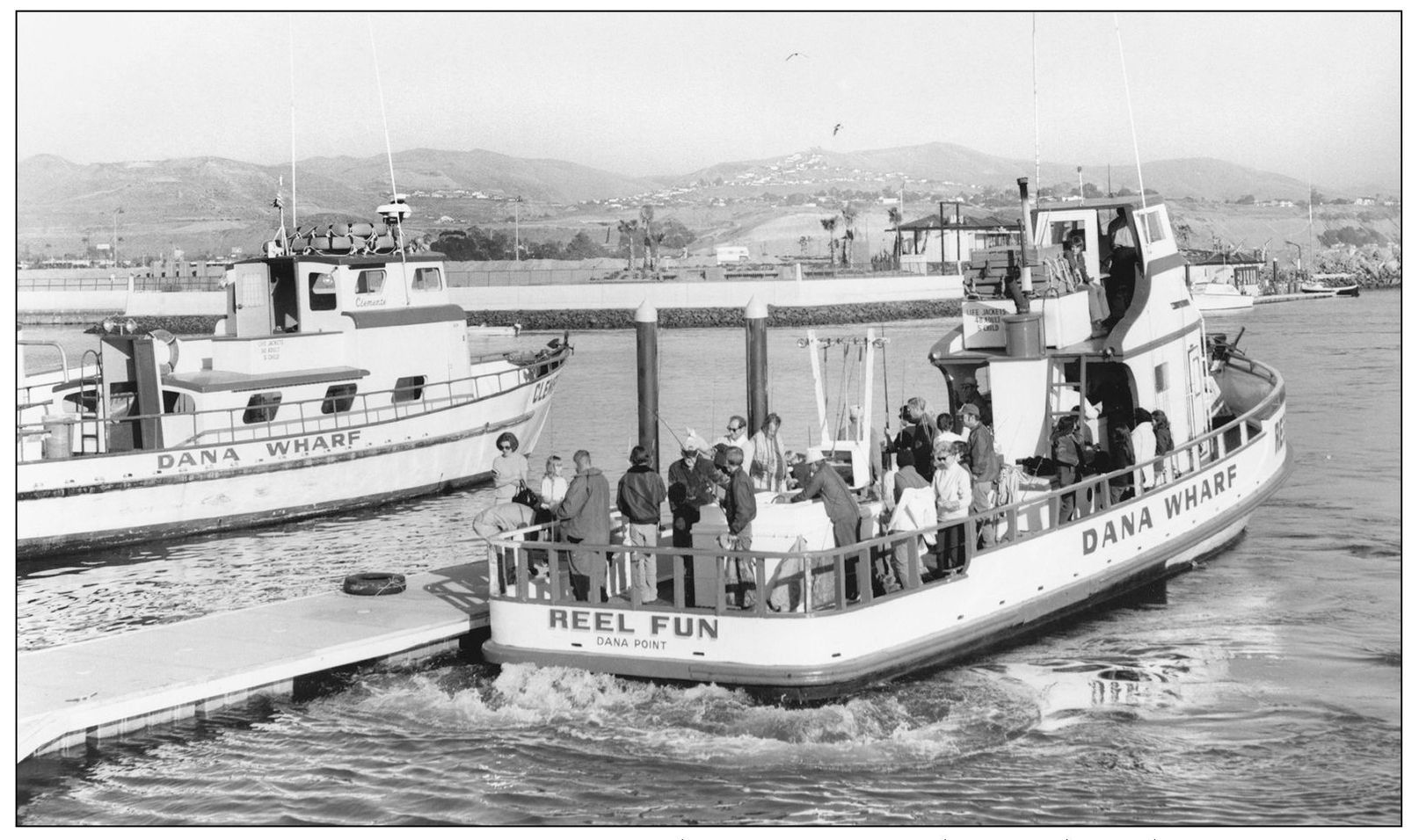

DANA WHARF SPORTFISHING. A resort port deserves a seasoned sportfishing fleet. Dana Point’s fleet played a significant role in local life long before the city became a vacation destination. After years at San Clemente’s municipal pier, Dana Wharf’s operation moved into this harbor as it opened in 1971. Its vessels offer a range of fishing trips and whalewatching cruises. The ships are a highlight of the harbor’s annual Christmas boat parade. (Photograph by the author.)

FANGS, THE GREAT WHITE SHARK. Suspended from a sling on the launching ramp crane, this 18-foot great white shark was an unusual catch by the Dana Point commercial fishing vessel Comanche in 1976. Landed alive after a five-hour fight, the two-ton fish was transported to Sea World San Diego, where she was exhibited. In the moving process, her jaws opened for the public that gathered, giving her the nickname “White Fangs.” (Photograph by the author.)

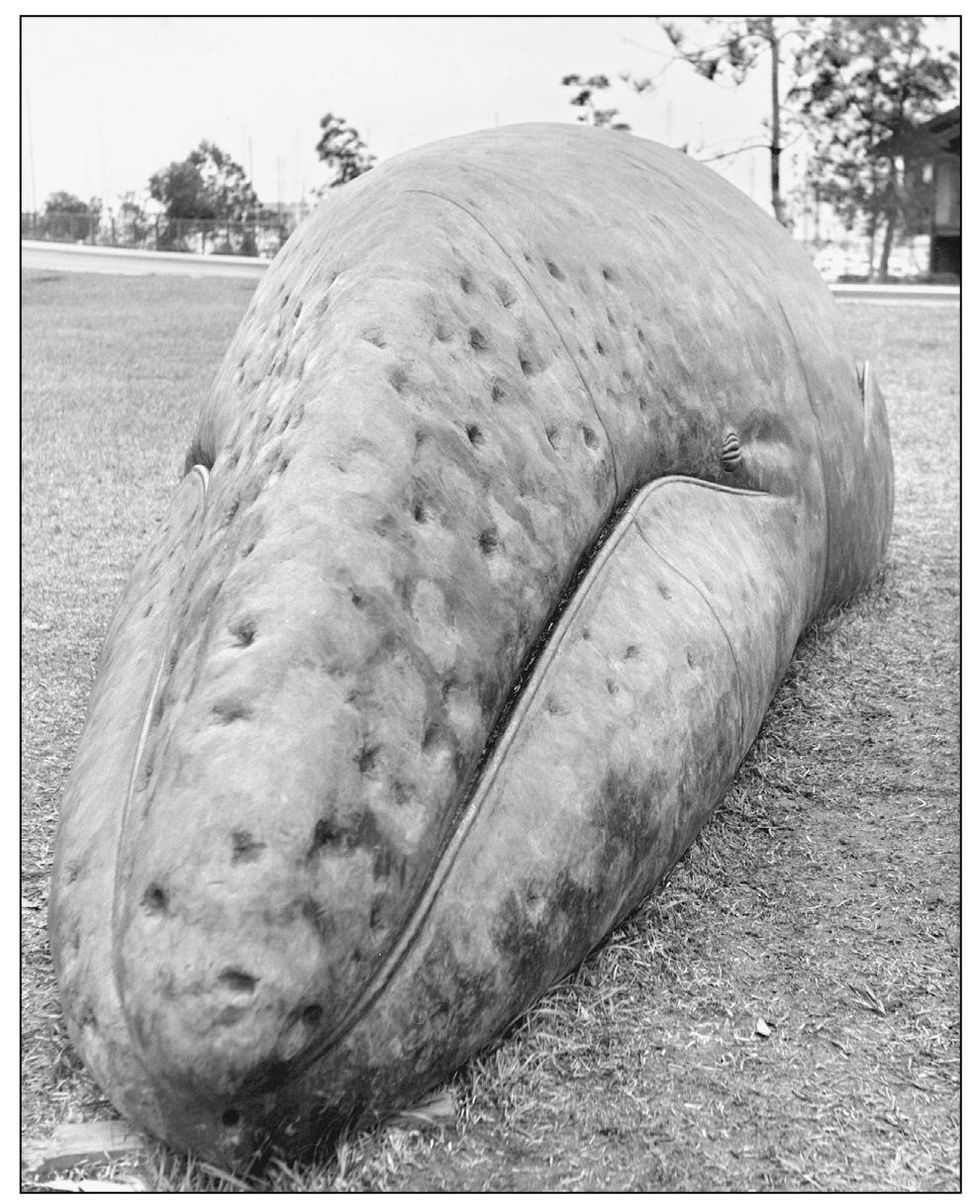

THE INCREDIBLE HULK. This five-ton newly dead basking shark was declared a navigational hazard when spotted floating just outside the harbor in 1978. The 24-foot fish was hoisted into the largest dump truck available, its tail dangling over the side as it rode to the county landfill. This second-largest fish species in the world is toothless, with filter-feeding gill-rakers instead of teeth. Its name around town became “Gills.” (Photograph by the author.)

WHICH IS THE REAL WHALE? These four whales all played a large part in Dana Point Harbor’s annual Festival of Whales, which began in 1972. “Sandy,” the 40-foot ferro-cement one at left, was displayed in the harbor one year, so visitors could see the actual size of the gray whales that swim by each winter. The theme of the festival that year was “Whales on Land and Sea.” So realistic was Sandy that several dead beached whale sightings were reported to the harbor patrol. (Photograph by the author.)

FIN WHALE. During another Festival of Whales, this 50-foot fin whale made of ferro-fiberglass came to rest in “Sandy’s” spot. Its smooth surface was an immediate attraction for youngsters to climb on and learn. Like the gray whale, the fin whale is a toothless filter-feeder. “Pheena” stayed long enough to smother the grass underneath her, so a permanent topiary whale, “Herb,” was planted there at Dana Point Harbor Drive and Island Way. (Photograph by the author.)

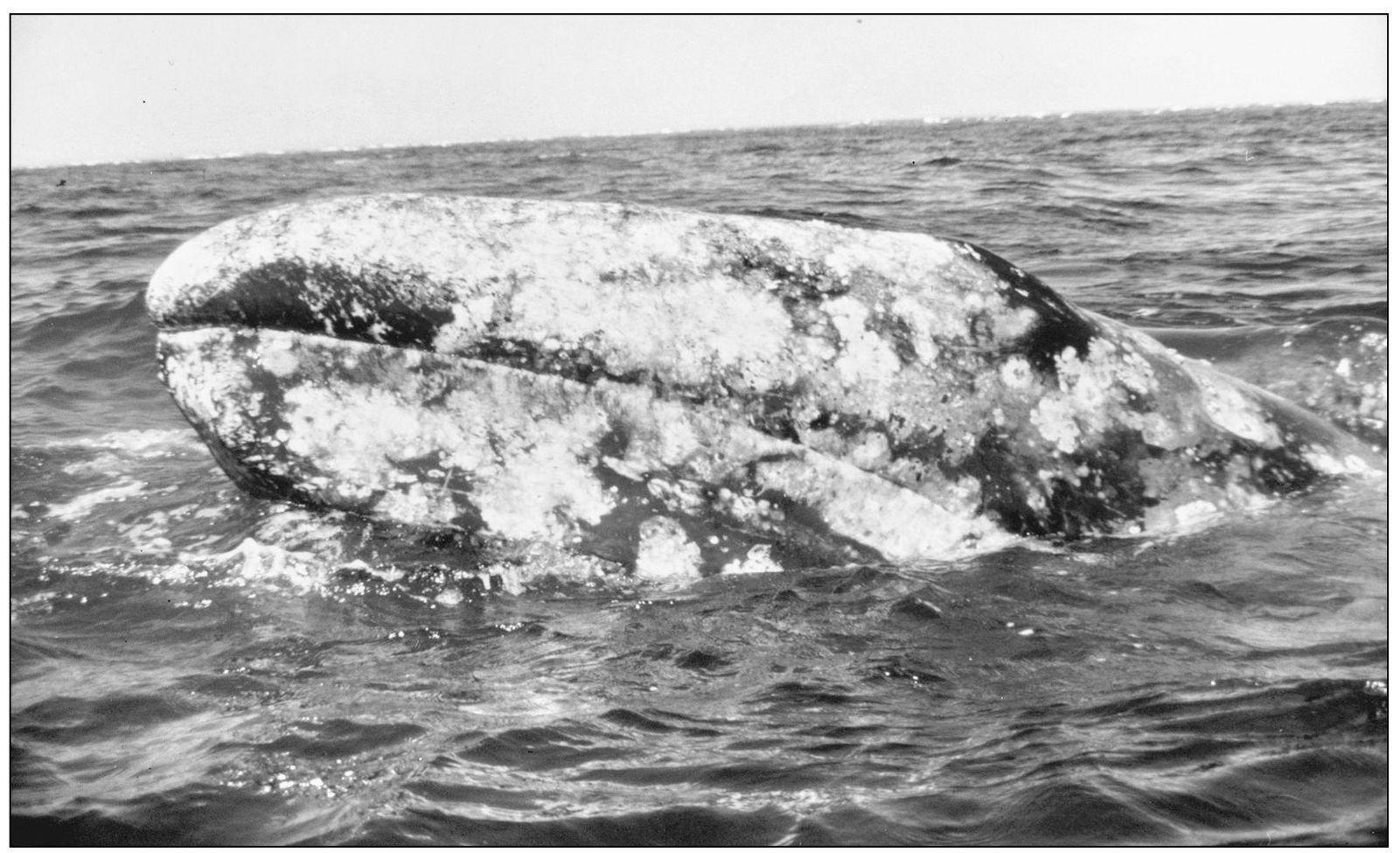

GRAY WHALE WITH BARNACLES. This is the head of a real gray whale, whose migration is celebrated as pods of its species visit the Dana Point coast each year. Their successful return from whaling days was brought to the state’s attention by Festival of Whales devotees, earning it the honor of becoming California’s official marine mammal. Barnacles attach themselves to these slow-swimming whales, filter-feeding along with their host. (Photograph by the author.)

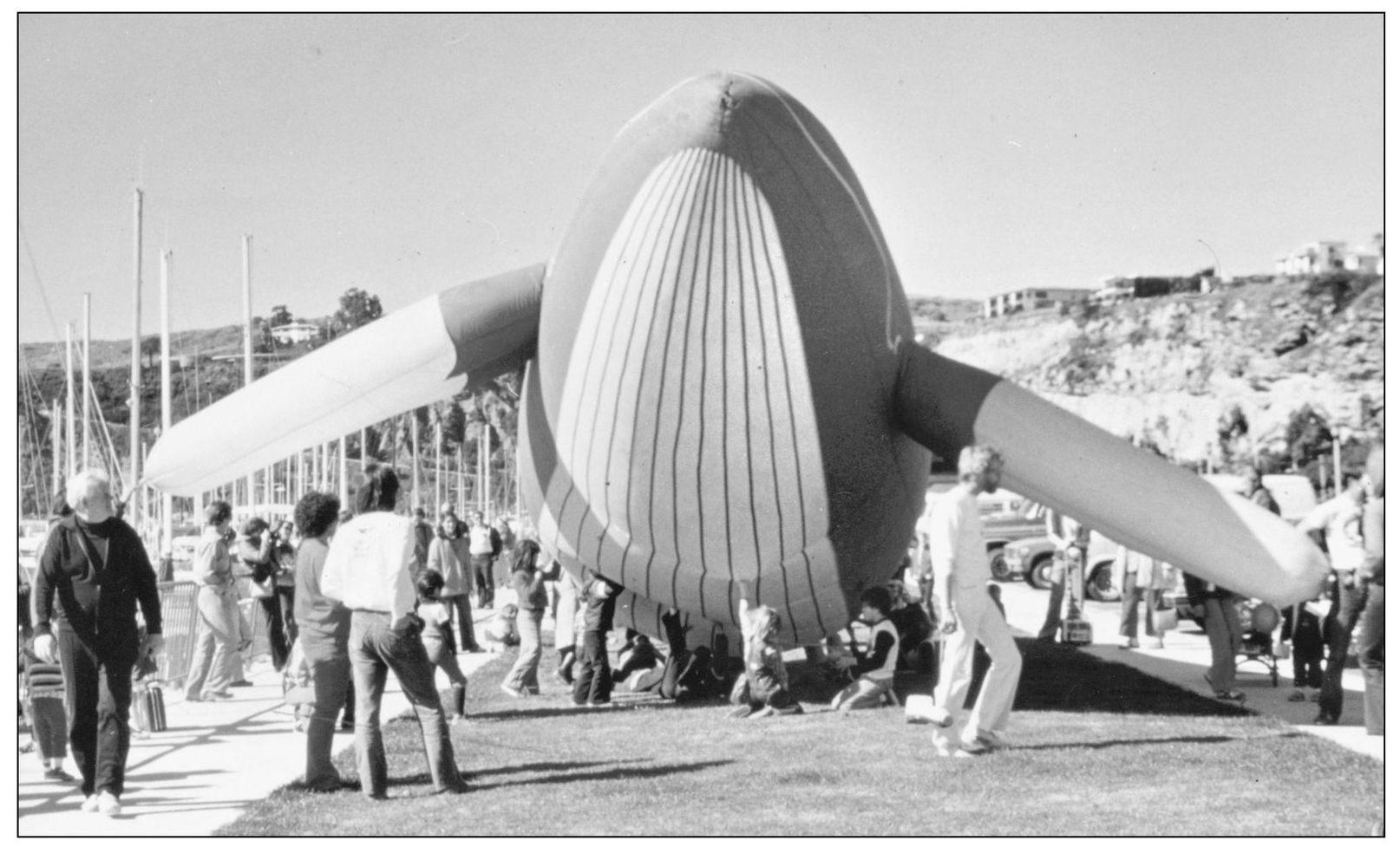

“FLO,” THE HUMPBACK WHALE. During one Festival of Whales, the enormous air-filled Flo joined visitors, floating along the children’s parade route propelled by dozens of supporting hands. She fulfilled that year’s theme: “Whales on Land, Sea, and Air.” Humpback whales are sometimes seen feeding along this shore. Namesake Dana reported sighting finbacks and humpbacks, as well as the dolphins still so active in these waters. (Photograph by the author.)

HISTORY REPEATS ITSELF. While the Festival of Whales began in 1972, mention of Dana Point’s association with this sea mammal was made in 1927, in the January 30 edition of the Los Angeles Examiner, as the early development of Dana Point was being announced. This caricature ties the name of the place and the three-masted ship Alert, the second vessel that brought namesake Dana here, with the visit of the whales.

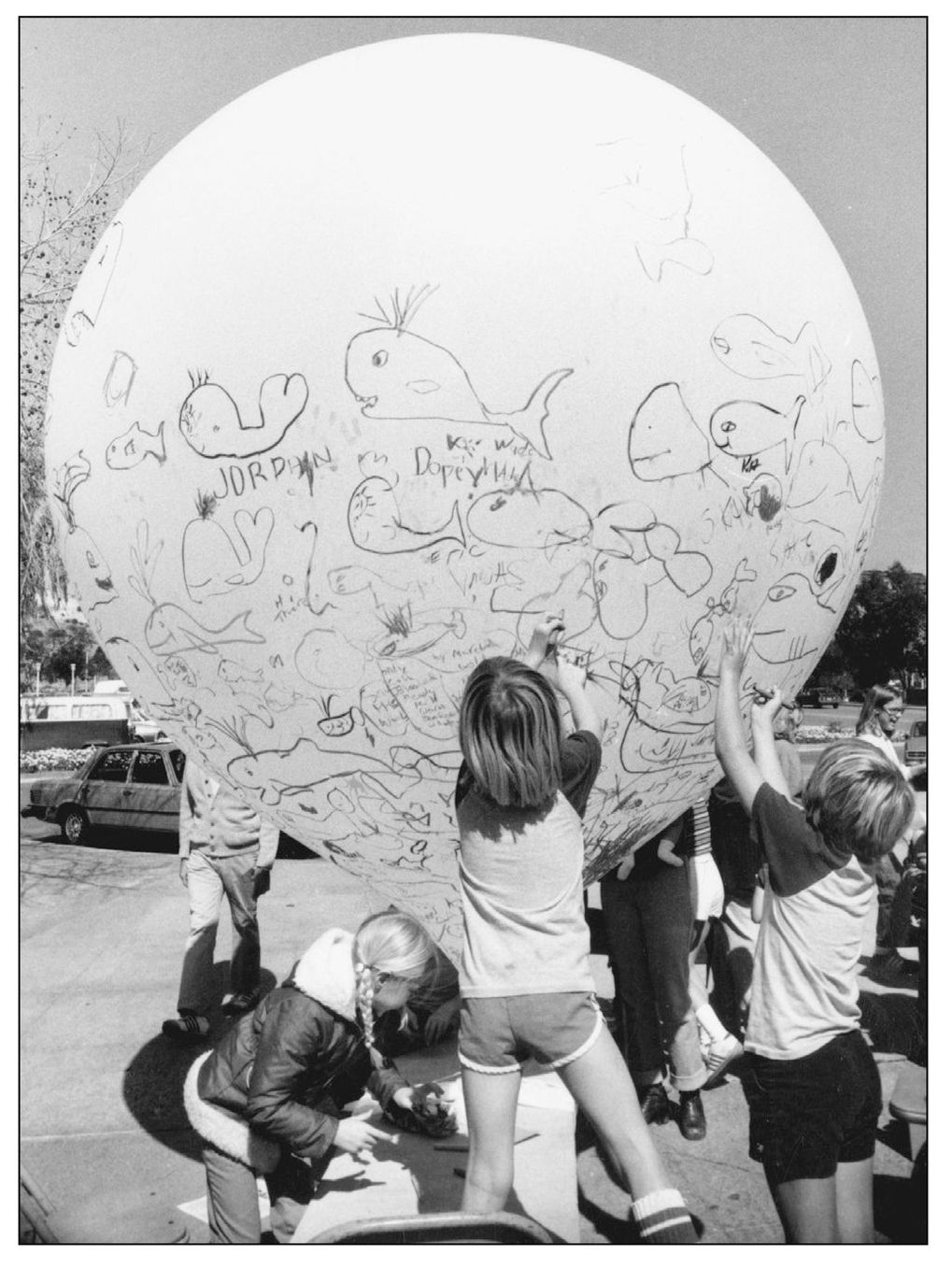

KIDS AND WHALES. Children visiting the Dana Point Festival of Whales one year were invited to draw their vision of a whale on a real weather balloon filled with helium. The finished work of art was hoisted atop the buildings of Mariner’s Village for all to see. Other special festival events of the past included air-to-seato-land demonstrations by the United States Navy’s underwater demolition and parachute teams. (Photograph by the author.)

FILLING UP A WHALE. The local elementary school, R. H. Dana, one year marked the annual visit of gray whales by painting a full-sized outline of the celebrated marine mammal on their schoolyard. Then this class, as part of their study of whales, sat inside the outline; they needed to invite another class to join them to even begin to fill the vast space. (Photograph by the author.)

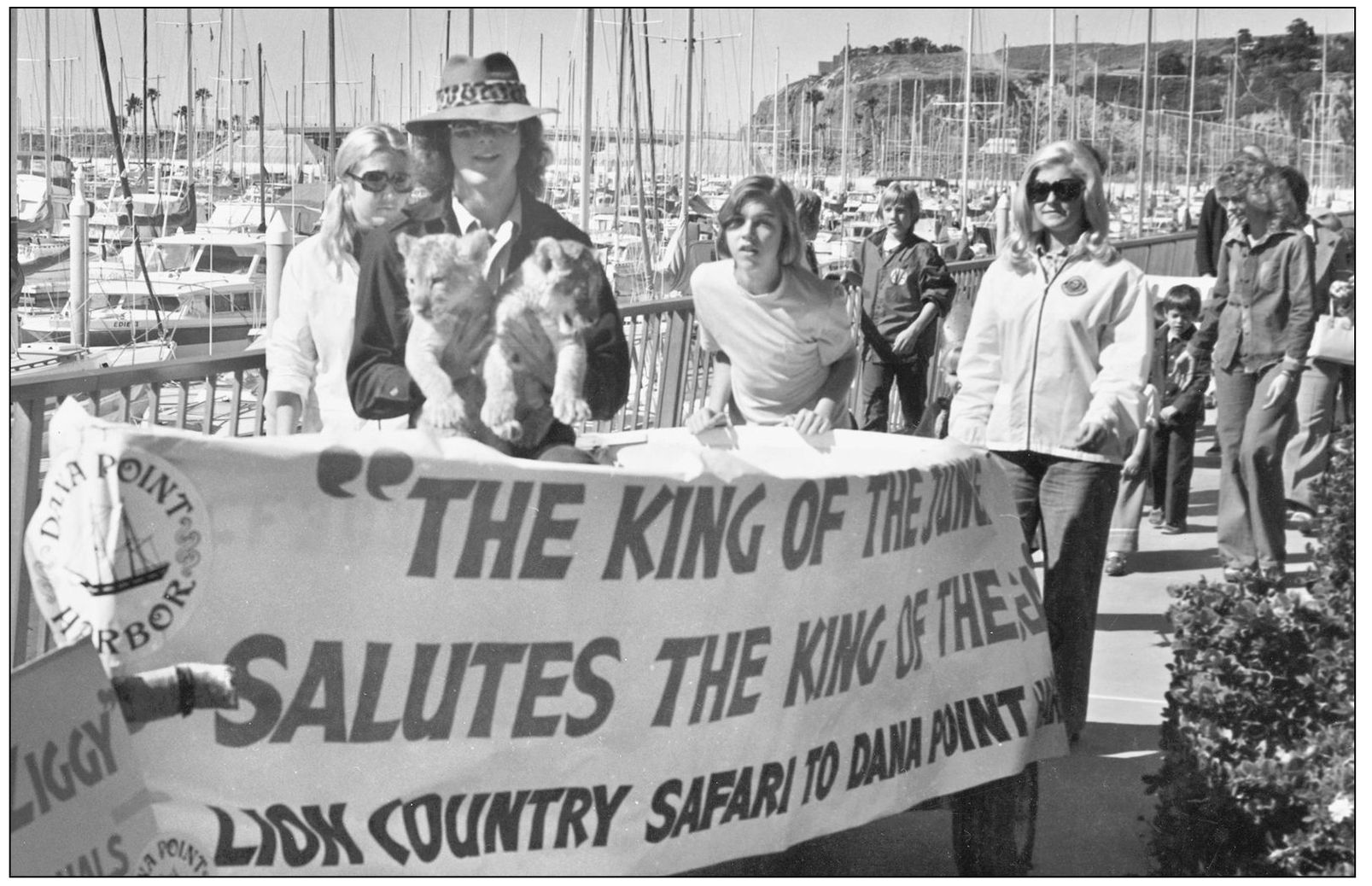

FIRST FESTIVAL PARADE. The Festival of Whales parade, now adult and motorized along Pacific Coast Highway, began in 1972 as a children’s parade along the marina walkways. Grand marshals that year were a pair of lion cubs that paraded on a trailered boat, announcing that “The King of the Jungle Salutes the King of the Sea.” The cubs were residents of Irvine’s Lion Country Safari. Disney’s Donald Duck was grand marshal in another year. (Photograph by the author.)

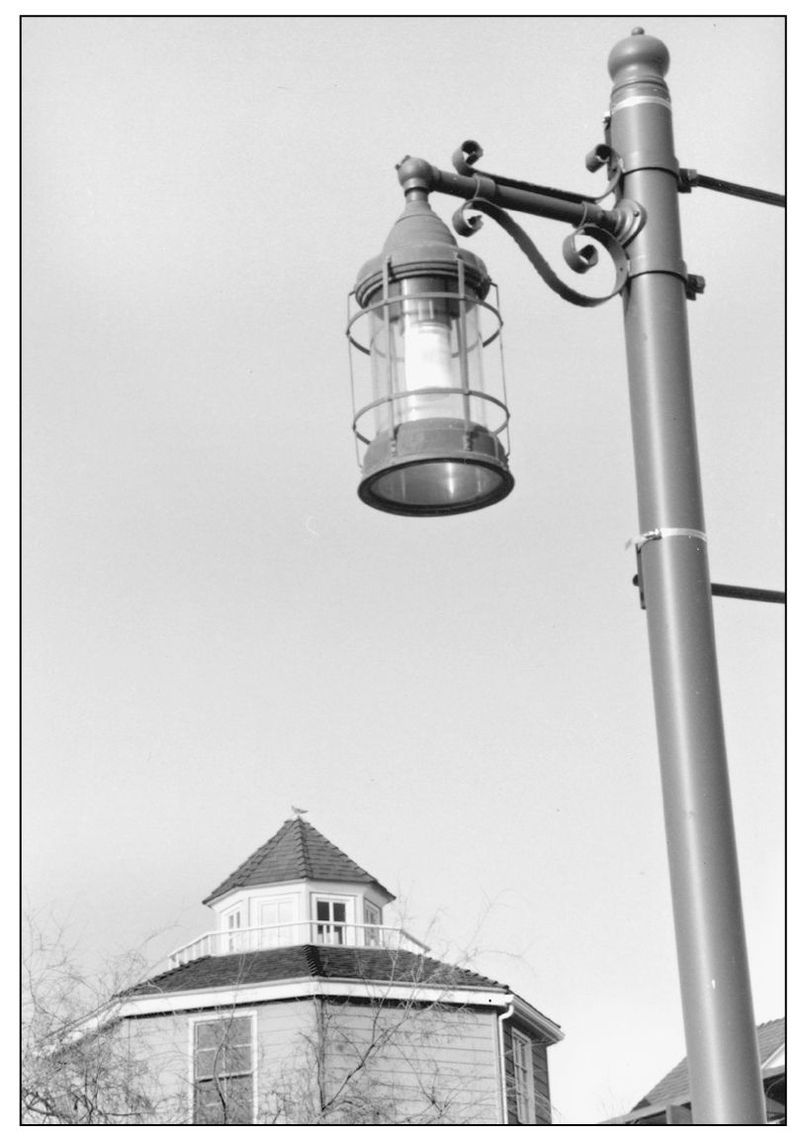

LANTERNS PRESERVED. Most of the lanterns that lit the streets of the original 1920s town disappeared during the lean 1930s. Some went to war as scrap metal in the 1940s. Fortunately 15 lanterns were saved and restored in the late 1980s to light La Plaza Park when it too was refurbished. The pictured tower on La Plaza reflects the New England Seacoast theme the 1980s Specific Plan required for commercial buildings. (Photograph by the author.)

CAPISTRANO BEACH PARK. It once held the Doheny beach club, razed in the 1960s. Early palisades homeowners were deeded access to this strand, so fences around it were cut for entry to “Hole in the Fence Beach.” The private-public issue was solved in 1980 when the County of Orange bought 1,500 feet and the state acquired a portion to expand adjacent Doheny State Beach. Under this park’s sand lies the beach club’s historic pool. (Photograph by the author.)

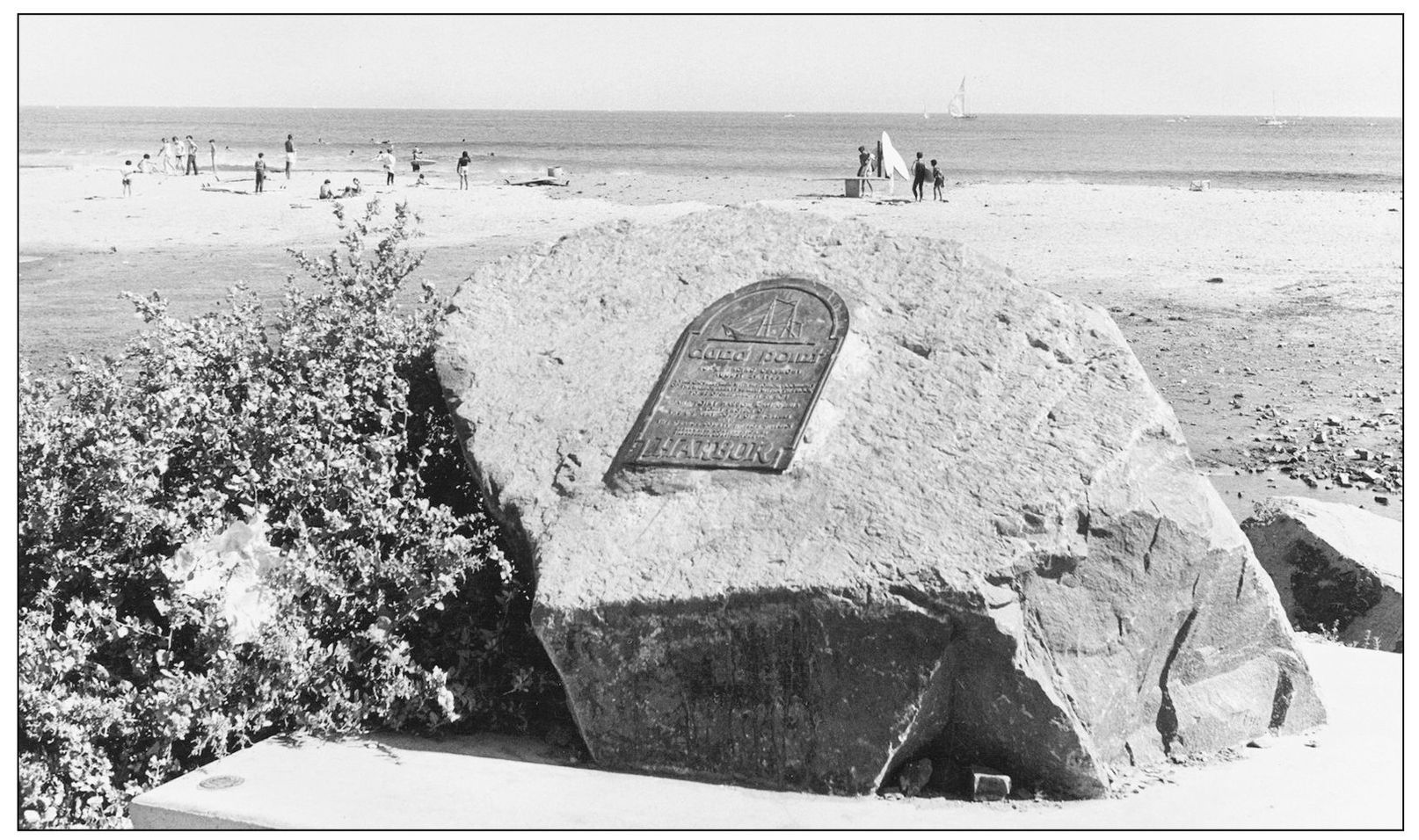

HARBOR TIME CAPSULE. Where Doheny State Beach meets the east jetty lies an enormous rock that was given a special role. It holds the Dana Point Harbor time capsule, filled with photographs and memorabilia by citizens and organizations as construction began. A beach barbecue is scheduled for the 50-year anniversary capsule opening ceremony on August 29, 2016. Tickets given out at the 1966 dedication will bring a free barbecue dinner “when presented by original owner” at that future date. (Photograph by the author.)

NEW TOWN CENTER. Dana Point’s major civic project of the early 2000s is the redefining of Town Center, which starts at this split of Pacific Coast Highway and Del Prado. Significantly it lies between the city’s two other major transformations of the decade: harbor refurbishing below and headlands development above. Town Center must be traffic, business, and pedestrian friendly while retaining touches of its 1920s origin. Past, present, and future meet at this intersection with Street of the Blue Lantern.

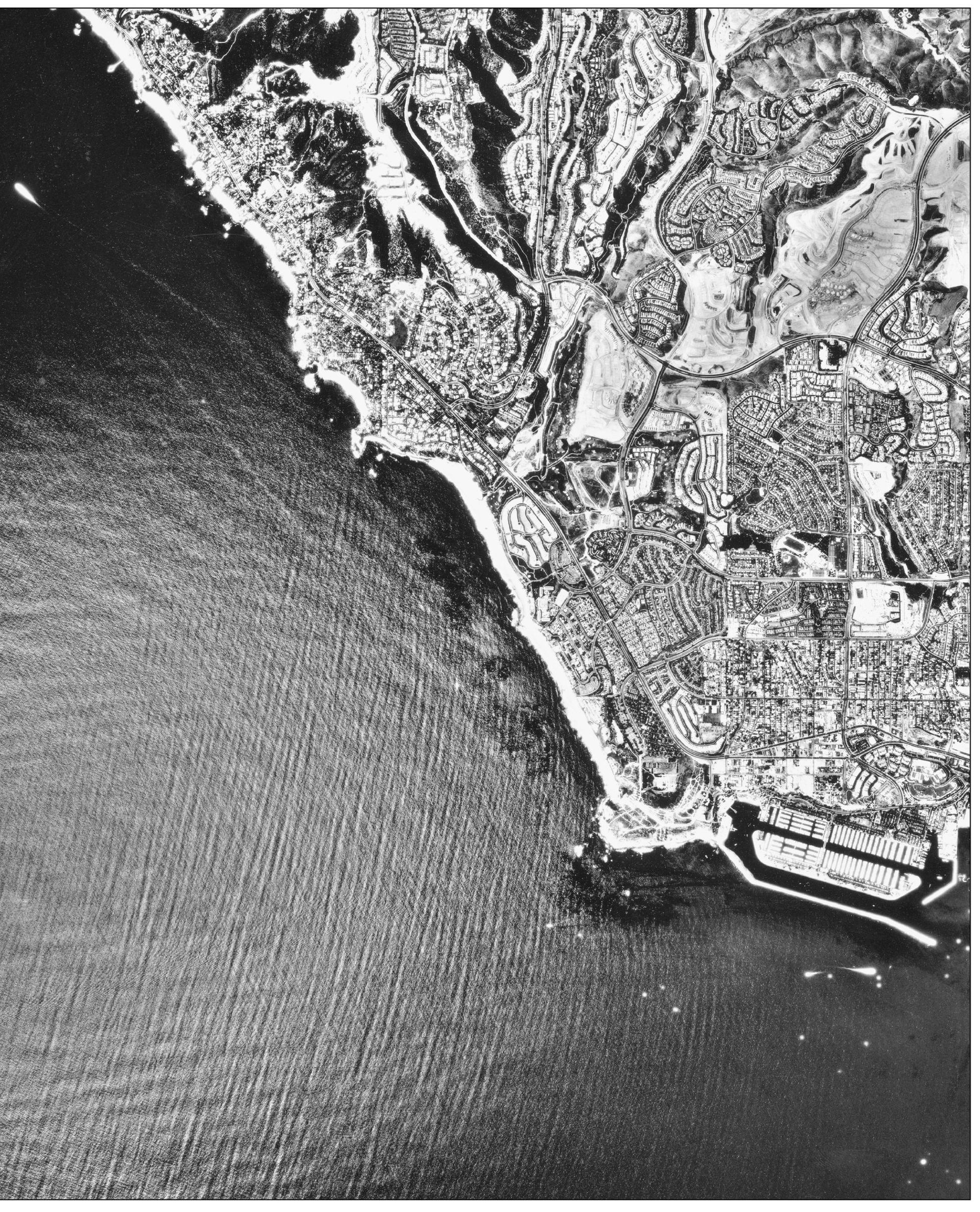

AERIAL PERSPECTIVE OF A CITY, 1989. Geography has been kind to Dana Point. Its varied vistas include panoramic views of the ocean, the mountains, the valley, and the canyons. While from an aerial photograph it may appear relatively level to anyone who has not had the pleasure of being there, the modern build-out has generally taken advantage of its varying elevations. Hilly terraces have become residential communities. Storied cliffs still surround the anchorage where its history began.