EIGHT

Nehru’s Foreign Relations

We have constantly kept two points in view in framing our

foreign policy: one, to avoid vilification of any country and

two, to work for peace in keeping with our principles.

—Nehru

Having accompanied Prime Minister Nehru to 22 countries, I can say that to JN, the most crucial question was, ‘Will the time be suitable?’ He spent a good deal of time thinking about when to go; but what to do there and what to say did not bother him much. To him the timing was most important and JN could judge the exact time to visit a country to the exact, propitious second.

On his visits he saw very little of any country. The face that any country presents to a VIP is the same. In every place in the world, there are the same guards of honour, the same introductions, the same arrangement of cars, the same fussing protocol officers, the same banquets, the same drive around the town to see the new buildings put up by the management at great expense, even the same mistakes and the same confusions, the same apologies, and the same relief when the visit ends. Anybody who visits another country as a VIP with the fond hope of seeing it is mistaken. Not for him the colours of a bazaar, the bargains in a side street, or the human squalour of a slum area, nor the quiet mind-your-own-business attitude of the peasant, the rush hour in a factory, the small restaurant where a good-looking girl serves national dishes, or the smokefilled cabaret where music suddenly strikes a light in your heart, as you wonder what the fun is all about. For Nehru there was cheering, curious crowds, and in every country they seemed to greet him in almost the same way—such heavy crowds that you could not even make a note of the shop where you saw some local finery and wanted to buy it.

No other foreign leader or statesman was given such a reception in all the countries he visited. We, who were privileged to be with Nehru, in the grand triumph of his life, felt great pride and a profound respect for the country that had produced him—and a sincere affection for the great nation that had honoured him, and in honouring him, had honoured India.

My first foreign tour with the Prime Minister was to Burma1 in May 1953. JN with U Nu, the Prime Minister of Burma had planned a joint tour of the border to study the conditions in the Naga territory on each side and to devise plans for improving them.

On the long journey back from Kohima that evening, I sorted out my impressions on U Nu. He was a close friend of Nehru and one of the most pious and good statesmen that the world had at that time. He was surprisingly gentle, ever smiling and wise for the age of 45. JN and he exchanged friendly banter.

U Nu remarked, “Panditji, I like your Vyjayantimala very much.”

Panditji looked at me, “Kaun hai yeh Vyjayantimala?” (who is this Vyjayantimala?)

I said, “She is an actress, who dances very well.”

So he said, “Oh yes, yes, yes.”

One remark of U Nu was interesting, “You know Panditji—it was fortunate for Mr Subhas Bose that the Japanese did not come to India. If they had, Mr Bose would have found it difficult to free himself and the country of them.” I could see that he was contrasting the peace and order on our side with the troublesome situation the Japanese had left behind in Burma.

1 Now known as Myanmar.

My next visit was to Egypt. I went ahead and reached there on 21 June 1953. The Prime Minister reached on 23 June from Geneva. A new government led by Naguib and other army officers was in power.

Before the PM’s arrival, I had a chance of meeting and talking to Naguib and several of the Junta officers. Most of them were very young and immature—not even well read—with no pretensions to culture or intellectual attainments. Naguib seemed to be the only exception, but even he did not give the impression of being a thinker. The real brain behind the coup was Gamel Abdel Nasser, a young colonel, who was then the No.2, but seemed to be the most determined of all. He was obviously a good conspirator and the strongman of the group.

Soon after arrival, JN and Naguib were closeted together over the Suez Canal dispute. The members of the Revolutionary Council (Junta) asked the PM to a river picnic on the Nile. JN was quick to take on the invitation. He gave them a long talk on the Indian Independence movement and the appreciation of Middle East politics. They heard him most attentively, surprised “that one small head could carry all that he knew.” JN, I think, charmed them completely and impressed them so much that one could read his words and thoughts in the subsequent statements made by the Egyptian leaders.

The next month, Nehru paid a visit to Pakistan. Ten years earlier the idea of Pakistan seemed preposterous to us all. Even its main protagonists in the Muslim League did not seem to take it seriously.

Exactly 10 years later, I was in a plane bound for Pakistan. What we had thought was impossible and illogical had come to pass.

The roads in Karachi were lined with bewildered people. The common man didn’t know what to make of the occasion. Arches, crowds (silent yet amused). Plans had been laid very thoroughly to give a grand reception.

Lunch was arranged in the Governor General’s house. We sat with the great men of Pakistan and some of their enormous wives. Ghulam Mohammad, Zafrullah Khan, Mohammad Ali, Gurmani, Begum Khaliq-uz-Zaman and Begum Qureshi were among the lot. Food was plentiful, quite unlike Rashtrapati Bhavan, Delhi. Everybody was very nice and spread goodwill. Mrs Vijaylakshmi Pandit spoke vivaciously. JN liked to take her on such missions to avoid the trouble and the danger of being sociable himself.

In the afternoon began the historic meetings between JN and Mohammad Ali. That took place in a room in the Governor General’s house. I was never able to ascertain fully what they talked about—except that it was announced that they discussed Kashmir, evacuee property and Sikh gurudwaras. But one could imagine the talks must have been difficult. JN was in a stronger position. He knew the facts and figures better than anybody else and not only did he have the authority of the Cabinet, he even knew that in the event of any departure from the set norms, he would be able to secure the backing of the government and the country. Mohammed Ali was not on the same secure ground. Even in the Cabinet, the older men and the seasoned India-baiters did not trust him. He was young and a nawab—too affable, shook hands with everyone, did not know ‘bania imperialism’, had never dealt with ‘Bharati intransigence’. In West Pakistan, he was a Bengali like the vacillating Nizamuddin. To the Punjabi and the Pathan, he looked suspiciously like a well-fed Hindu banker of Calcutta, interested in football, luxury cars, cigarette lighters and dinners at Firpos.2 It had been calculated that for every hour poor Mohammed Ali discussed Indo-Pak problems with Nehru, he would have to face the Cabinet for six hours explaining what each of them had said.

Dinner in the Governor-General’s house was a quiet affair—only the Indian team was present with Ghulam Mohammed. JN related an anecdote about Maulana Mohammed Ali.3

JN said they were going from Kalka to Simla. As they passed the Solan distillery, the Maulana said, “There goes spirit of the British army.”

“I suppose you’d call Coca Cola the spirit of the American army.” JN remarked, “The other day somebody gave me a bottle of this stuff, which I normally never drink. When I held the bottle (of Coca

2 Then a popular restaurant in Calcutta.

3 One of the Ali brothers who took part in the ‘Khilafat’ movement led by Gandhiji.

Cola) in my hand, an enterprising young man came up and said, ‘D’you mind, I want to take your photograph.’ I was so disgusted that I threw the bottle away.”

JN continued, “The story has an epilogue. I told it to Gen. Naguib in Cairo when he asked me whether I liked that drink. ‘One fellow,’ Naquib said, ‘did the same thing to me but he did succeed in taking a photograph of me drinking the stuff and used it as an advertisement. I put him in prison’.”

JN’s press conference in Karachi was a masterpiece of evasive generalities. “We must be friends,” he said, “and what we need for being friends is to be friendly.” It became a great hit. We stood at the tombs of the Quaid-e-Azam (MA Jinnah) and the Quaid-e-Millat (Liaqat Ali Khan) on the morning of the 26th July. Wreaths were placed. Photographs taken on the occasion appeared prominently in the Hindu Mahasabha press. ‘Honour to the Man Who Hated India and Indians’; ‘Tribute to the Muslim Who Made Pakistan.’ In JN’s mind there were no tributes. “Here lies the man who was the very antithesis of my master, Gandhi. Here lie the men whose profession was hatred—who sedulously preached war on my country and my people. Yet, I must not give way to hating them. That would achieve the object they desired. They hated us—and hate has proved to be their downfall. Should we make the same mistake?”

His talk to the officers of the HC (High Commission) was more revealing. A member of the HC’s office asked him whether it was true that the elder brother had decided to give what the younger brother demanded. The question was crudely phrased. I expected a crushing reply. JN, however, said slowly and thoughtfully, “It is not a question of big brother and small brother. We must look at things in a more intelligent way—and with durandeshi (a vision).4 We have to see what will be good for our country, not only today but tomorrow and the day after. We must apply one crucial test to our policies—will this do good to our country? Not as some people are apt to do to apply the other test—will it do harm to others?”

He continued, “We have constantly kept two points in view in

4 Nehru sometimes gave a speech or talk in a mixture of English and Hindi/Urdu.

framing our foreign policy: one, avoid vilification of any country and two, work for peace in keeping with our principles.

“India and Pakistan are so closely bound together that there can be no indifference between us. Either it must be hate or love. The leaders of Pakistan seem to have realised that hate has proved disastrous—and appear to be moving towards more friendly relations with us. If they continue this policy, it will be beneficial to them as well as to us.”

“There is a tendency on the part of our legations,” he added, “of trying to impress the diplomats of other countries. That is not the purpose for which our representatives are sent abroad. Their purpose in a foreign land is to impress the people of that land with their simplicity, their straight-forwardness and their good behaviour. We must not emulate the representatives of richer countries or try to be lavish with our limited resources.”

“India,” according to JN, “faces only one danger, and that is not from any other country but from the disruptionist forces within.

“In the past we were a great and prosperous land; we had many great and courageous men. Then, what was it that brought us down and placed us under the subjugation of a foreign power? We were overcome because of the disruptive tendencies within us—by the disunity created by caste, religion and province.

“Should we repeat again the blunders of the past which brought about our downfall? Shall we fritter away our strength in petty quarrels over trifles? Or should we devote our strength and our will to developing the country, reducing the difference between rich and poor, in building up industries, in spreading knowledge of science and applying it to our everyday needs; in establishing peace within us so that the culture of our country, stunted by foreign domination, may grow on ground hallowed by the past, aided by the light of the present?

“Should we develop the potential resources of the country, or squander our energies in suspicion and hatred; in preparing for war which will ruin us?

“It is our aim to establish a just and honourable republic. We shall be friends of other nations, and shall derive whatever advantage we can, material and spiritual, from their resources and their sciences. But we shall not endanger our independence or hamper our discretion. We will be independent in every sense of the word.”

This was the message of JN. He had the two requisites of a great leader—a gentle nature and a great spirit.

In accordance with his stated foreign policy ‘to work for peace in keeping with our principles’, JN had worked tirelessly for one week and it culminated in the Indo-China cease-fire agreement in Geneva. JN was outwardly tired, but inwardly there was a great joy in his heart. He had initiated the cease-fire move six months earlier, which had indirectly led to the Geneva conference. The Colombo conference, of which he was the spokesman, had given a lead to the countries of the world which had undertaken the responsibility of ensuring peace in the area after the cease-fire. Krishna Menon, his emissary, had assiduously worked for peace in Geneva and London. And finally JN’s meeting with Chou En-lai had assured the Chinese also of our honest intentions. The war which lasted eight years, had at last, ended. For the first time in 23 years, there was no fighting anywhere in the world.

I said to him, “You must be very happy about the cease-fire in Indo-China.”

“Yes,” he replied sedately, “It’s a good thing. But it means a very heavy responsibility on us.”

On our way back to Bhopal from Sehore in May 1954, we had an interesting discussion on international relations, in the course of which JN said, “I am afraid America has a future before it which is full of knocks. A pity, but there it is. American policy has tended to become more and more removed from reality. They will get hard knocks—like Korea—and then they will see the real issues in world politics.”

Having developed an equation with the Chinese Prime Minister Chou En-lai, Nehru invited him to visit India. In June 1954, when it became known that Chou En-lai was scheduled to arrive, I met JN and asked for his instructions. Instead of giving any, he asked me how I thought it should be arranged. I said I did not agree with the plan of excluding the public from the programme prepared by his office. I would, on the other hand, change the venue of the reception to the IAF portion of the Palam aerodrome, put up barricades and allow the public to be present. From all points of view it seemed to me to be the best way of giving the reception. He seemed to agree with me, though he did not say anything.

The plans were changed. The Central Public Works Department (CPWD) was able to construct the barricades in record time, which I never thought was possible.

People started clapping when the Air India plane landed at Palam and the Prime Ministers of India and China shook hands. Chants of “Chini–Hindi bhai bhai” rent the air.

Chou En-lai was a big hit in India. The fair-looking Chinese, who had played female roles in college dramas and led the communist army to victory, who had consigned a large number of people to death to re-organise his country, and who, a few days earlier, had achieved a diplomatic victory at Geneva with his unrivalled, suave demeanour and wit had won the friendship of the Indian people.

Naju and I turned to go home with a hundred questions. What will be the result of this? Does this mark the beginning of a new era of friendship and understanding? Or will it disturb us in the future?

Chou En-lai invited Nehru to pay a visit to China that Nehru gladly accepted. In October 1954, I accompanied the PM on a tour of the countries of South-east Asia and China. We landed first at Rangoon and the reception we received at the airport was, guardedly speaking, a tumultuous one. Before our Dakota touched down, cameramen were all over the field. We could perceive U Nu’s smiling face as the door opened. Multi-coloured caps darted about. Burmese ladies in white nylon blouses seemed drowned in the tide of humanity that swept over us. Pushing, struggling, JN ordering people about — cameramen in front of the guard of honour—bringing respite only while the band played ‘Jana gana mana’ and then we started struggling again in the sea of people.

Shouts of “Nehru ki jai”, “Nehru zindabad” rent the air. Still struggling and pushing, we climbed into a jeep—JN smiling a lot, then angry. People ran after the jeep. The reception was so boisterous that one felt that it would be difficult to extricate JN from that place.

Also, in Rangoon, there was a festival of colour throwing going on; not our Holi type, but they played with water and we were all drenched to the skin on the day that we spent there during that festival.

The Ramakrishna Mission had arranged a function in the evening, which became a free-for-all struggle. I overheard a Burmese policeman saying: “Wherever there are Indians, there is confusion.”

On 17th October, we flew over the Mekong River and glided into Vientiene, the capital of Laos. Dr Khosla, Chairman of the International Commission came forward to meet the PM and then introduced his Polish and Canadian colleagues. There was much applause in the reception at the airport in Bangkok. Then we moved on to more interesting places in Cambodia and Vietnam. At all these places, JN asked me to stay close to him.

We reached Hanoi, the capital of North Vietnam in the evening. Having come all the way to Hanoi, I was disappointed I could not meet the great leader of Vietnamese, Dr Ho Chi Minh.

The next morning, when I was walking up to the PM’s room, I found JN coming out with a fair and good-looking Vietnamese. They bade goodbye and then the stranger kissed Indira with a resounding smack on both her cheeks.

“Look after him well,” he said to Indira.

He was Dr Ho Chi Minh.

There are few men in Asia who were loved and honoured as much as Dr Ho Chi Minh. He was in the Gandhian tradition of patriots—a man who was extremely simple, loveable and devoted to the people. He remarked when he was chosen President, “I was chosen President because I had nothing—no family, no house, no fortune, and only one suit of clothes; the one I am wearing.” Small and delicate, he was a symbol of the suffering of his people for Independence, but like all who have suffered, he talked of friendship, help and fellow-feeling.

The man who worked as a waiter in Carlton Hotel in London and travelled all over the world as a cabin boy, the man who repeatedly appealed to France not to break its bonds with Vietnam, and believed in non-violence and yet took his men into the jungles to fight one of the fiercest wars of modern times, was this President of North Vietnam.

I asked JN later what he thought of him. JN replied, “He was very affectionate and good to me. He remembered meeting my father, and the message of congratulations I sent to him in 1946. All his life he has tried to be conciliatory and even now he harbours no ill will against the French.”

Then, JN smiled and added, “He told Indira, ‘I would very much like to kiss you, but I believe the custom of your country forbids it.’ Indira said, ‘It does not matter in such circumstances.’ So he kissed her on both cheeks, while Indira felt rather embarrassed. He asked Indira to call him Bah Mo—Uncle Mo—as the rest of the people of Vietnam do.”

We reached our final destination–China. As we got down from the aircraft at Canton, an officer of the Indian Embassy met us and escorted us to our place in the meeting. JN shook hands with scores of people, tidily standing in one block. Children ran forward with flowers.

In the streets of Canton, row upon row of healthy boys and girls, clapping, cheering and happy, greeted the PM. If it was an organised reception, it was certainly well organised. The flash upon flash of healthy laughing faces as the car went by left an indelible impression. It was a spontaneous reception—they felt glad to greet Nehru, the leader of the Indian people, who had brought peace to Korea and saved China from sacrifice. They cheered not only India and Nehru, but peace, which had been denied to their unfortunate country for almost a century.

The reception at Canton was a heart-warming one. There was so much that was new around us, and yet so much that smelt and looked like India. We drove through the streets—mile after mile people lined it in an orderly manner—they cheered us clapping, and we clapped back. They clapped harder.

The reception at Canton was not a patch on the one at Hong Kong that very evening. The Chinese airforce aircraft flew low over Peking the next day—the lake in the Summer Palace looked beautiful. We bade goodbye to our smart hostess in the olive green uniform, who had cheeks of the most extraordinary pink of ‘pinkiness’.

The PM was given a memorable reception at the Peking airport. Chou-En-lai introduced the notables. Masses of gladioli were given to the PM and his daughter. I, who was standing behind to take over the flowers, was mistaken to be a diplomat because of the white cap and the Chinese PM took me by the hand to greet the dignitaries. I shook hands with them, feeling touched and amused, and disappointed that I should always achieve greatness by mistake. More than a million people stood by the side of the road to greet the Prime Ministers of India and China as they drove through the streets in an open car, while the people clapped and cheered. All along the route, not a single police in uniform was visible. But on the other hand, every man from the public acted as a policeman in maintaining order and in guarding the leaders, while the cadre leaders made quite sure that none from their ranks wandered or got out of place.

While JN went to meet and talk with Chairman Mao and the leaders of China, we slipped away to roam round Peking. No restrictions were placed on us. We went everywhere accompanied by our interpreter who spoke English with a strong American accent.

A fact that struck me forcibly throughout our stay in China was that the Chinese communists were not fanatics of communist principles. They have been prepared to compromise; they have been merciful; they have avoided killings merely in order to enforce their theory. No one realised more than Chairman Mao that the success of the Eighth Route Army, which helped the communists to extend their sway over large areas, depended on the goodwill of the people. Everything that commanders like Mao or his deputy Chu Teh did, bears out the theory that the support of the people is more effective than the support of a theoretical assumption and the support of the people can only be secured if the army and the government put the principles before the people and let them apply them in their own way, gradually and effectively.

Chairman Mao and his men have been trained in the rough school of battle and civil strife. Unlike the Russian communists, who were overnight placed in authority over a large country, the communists of China have had the opportunity of extending their writ slowly and scientifically, trying out, applying the principles of communism in such a way that they did not incur the displeasure of the people, which would have hampered their progress more than anything obtained through forcible enforcement. The other advantage that the Chinese communists had was the absence of any serious and immediate threat to their existence, such as the one that faced the Russians.

China, like any true democratic country, felt that its strength lay in looking after the good of the people, and behind all that Mao and the Communist Party of China did, there was the tradition of a wise and noble people, a tradition that stretched back into the dim recesses of time, and the history of a people that had suffered greatly, yet lived well.

I met Chairman Mao for the first time at a reception given by the Indian ambassador (Raghavan). Mao appeared suddenly. His coming had been kept a security secret. He shook hands and said a few words to us through his interpreter. I was overawed by the occasion. Mao was a big made, bearish, round faced man with a prominent wart on his chin. Here was a man, I mused in a corner, who is today one of the greatest of men. No statesman or leader is as dominant in his country and in the hearts of his people. It has been given to few men to lead a small band of men, through untold hardships and tribulations and gradually extend that band into an army of millions to liberate a large country.

Chairman Mao was the man who had set up a new dynasty and in 1954 itself, one could see from the vigour and determination that they possessed that the communists would stabilise the government, set up industries, improve communications and make China a powerful nation again in the not too distant a future.

There is something about a great man like Mao that eludes definition. There were contradictions in him, as there were in Dr Ho Chi Minh or Pandit Nehru that were so easy to identify. And yet the mystery of it is that the spark of genius in them ensured that the particular course they took proved to be the best in the long run. I am of the view that there is no real consistency in great men. Like all human beings, they too are contradictory and vacillating; they say one thing one day and another thing another day. But their greatness lies in appreciating a situation in such a way that the course of action they suggest turns out to be the best. You might call it a sense of the prophetic, a knowledge of men and events, or just an intuition. Whatever it is, the real test

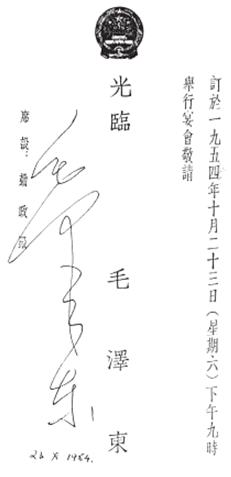

Autograph of Mao tse Tung on the invitation card, dated 23 October 1954.

of greatness is whether a man’s vision or view of the future is big enough and is justified by reality. If Mao dreamed of a socialist state while leading the battered army over the long march and fought and worked year after year for that ideal, did he in practice achieve it? If Nehru, in the days of British greatness, dreamed of an independent India and never lost sight of his vision of the future, was his vision fulfilled? If Dr Ho Chi Minh, small and slight, fought for an independent Vietnam when it was impossible, and eventually drove out the French, did he secure what he had promised to his people?

All men should be judged by their vision of the future, and the fulfilment of that view.

Canton, Hangchow, Peking, Anshan, Mukden, Dairen, Nanking—at each place the cheers became louder, the clapping more vigorous. At each place we felt that nothing could be better than the reception given there. Then we moved on and found that there was something better—Shanghai. There the airport was a mass of people waving gladioli flowers—there were so many flowers that they seemed to change the colour of the airport. The reception that China gave to JN has been reported by many observers to be an unprecedented one.5

A lot has been said about what JN wanted to do in China and what he did—what he wanted to achieve and what he failed to achieve. Each country had looked at that visit from her own viewpoint, and since there were two main power blocs, two rival views had emerged.

JN did not go to China to make a historical change. He said in Calcutta, before leaving for China, “I am going to China with no set purpose, but chiefly to pay a friendly return visit to that great

5 Pandit Nehru used to write lengthy letters to Lady Mountbatten after return from every foreign tour. In a letter to her, after return from China, he wrote, “I had a welcome in China, such as I have in the big cities of India, and that is saying a great deal. The welcome given to me was official and popular. One million took part on the day of arrival in Peking. It was not the numbers but their obvious enthusiasm. There appeared to be something emotional to it.” (Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, Vol. 27.)

country and to continue the talks started in Delhi with Mr Chou En-lai with a view to greater understanding of each other.6

I returned from the memorable tour of China and South-east Asian countries thoroughly impressed and happy. I could not understand what had happened but after my return from China I was suspected in my organisation (the Intelligence Bureau) of being undependable. I was placed in the category of ‘suspects’ for expressing views that were identical to those of the Prime Minister. It was clear to me that I had fallen from grace. I started getting an average of one raspberry per day from my chief.7 Something seemed to have happened when I was away in China that had led to this. The only reason I could think of was that my accounts of events in China had caused serious doubts among the powers that be as to whether they were not nursing a viper in their bosom.

I suppose the permanent services in any government are always conservative and more so the police. But in India, conservatism goes so far that it is almost counter-revolutionary. My only consolation was that if JN were in my place, he would have been sent out of service or certainly out of Delhi, by all those who are supposed to carry out his policy. Such is the enigma of Delhi.

The very next year, I was communicated an adverse remark in my Annual Confidential Report (ACR):

“His defect is that he is not always thorough, and resents criticism.”

When I look back at the events which enabled me to earn this ‘distinction’, I realise I got it simply because I went up to my chief and had it out with him. If I had not gone face to face, and asked

6 JD Bernal, FRS, was a Professor of Physics at Cambridge University. His research helped develop X-ray crystallography and he was the founder of molecular biology. He was a member of the communist party for some years. He knew Nehru since 1937. Nehru met Bernal in Peking and described to him his impressions of his visit to China. According to Bernal, “Nehru was obviously impressed and somewhat shaken by the enormous energy and enterprise with which the Chinese were conducting things. He would have liked to see something like that in India but he did not think it was possible in view of the heritage of the British and native capitalistic traditions.” (Bernal papers—NMML)

7 The Director, Intelligence Bureau, BN Mullik.

him to say why he kept on pin-pricking me on my files, this would not have happened.

That led me to one conclusion—are Indians as a race unused to manly conduct? It seemed to me that my chief might have preferred it if I had intrigued or gossiped behind his back. He hated me for facing him and making him feel uncomfortable.8

Despite what my chief thought of my work, I was not deprived of the responsibility of protecting the most precious life in the country. I accompanied the Prime Minister to the Asian-African Conference that took place in Bandung from 18-24 April 1955. Even before he reached Bandung, JN had several meetings with the PM of China. JN’s attempts were directed at ensuring that the conference did not fail because of China or Vietnam (both communist powers). It was obvious to us in Bandung that JN had patiently explained his object in convening the conference to Chou En-lai and had reached some sort of understanding with him. JN succeeded perhaps in assuring the Chinese that nothing would be done which would be directed against them, and it was because of this that Chou-En-lai adopted an amiable and friendly attitude throughout the conference, not only with those friendly with China, but with those opposed to it. Chou’s moderate approach to the Asian-African Conference was one of the causes of its success.

Turkey, Pakistan, Thailand and the Philippines came with the brief to wreck the conference if China or India showed the slightest intention to utilise any session for their own purpose. JN obviously knew what moves the West had been making. Probably, the West had tried to influence him too.

On the day the conference opened, the participating delegations were neither sure of the attitude of China, nor of the genuine desire of India to make the conference a success.

Dr Soekarno made a memorable speech. The orator of the east

8 Rustamji had high personal regards for Mullik and except for this one comment, he had, in several of his articles, paid glowing tributes to Mullik for his vision, his contribution to Indian police and his spiritual bent of mind. The remark in the ACR of KF Rustamji was declared ‘not adverse’ after a spirited representation against it.

and one of greatest in the world in those days, delivered his speech in a manner which created a profound impression. It was a ‘cry of defiance and not of fear’. It set the tone for the conference.

He said, “Our task is first to seek an understanding of each other, and out of that understanding will emerge a greater appreciation of each other, and out of that appreciation will come some collective action. Bear in mind the words of one of Asia’s greatest sons, ‘To speak is easy. To act is hard. To understand is hardest. Once one understands, action is easy’.”

As soon as the speech of Dr Soekarno was over, Turkey delivered a shattering blow to the unanimity displayed so far. The Turkish delegate demanded that all speeches prepared for the opening session must be delivered. A furious discussion followed. JN was obviously irritated and in protest, declined to make a speech. His impatience and irritability were noted gleefully by all the newspaper correspondents who were out to belittle him and the conference in the world press.

On 23 June, a statement was made after a luncheon party at the residence of the Indonesian Prime Minister, Dr Ali, in which the Colombo powers—Chou En-lai, Romulo and Prince Wan were present.

“The Chinese people are friendly with the American people. The Chinese people do not want war with the United States of America. The Chinese government is willing to sit down and enter into negotiations with the US government to discuss relaxing of tension in the Far East.”

I could not only see the mind of Nehru in the statement, but even the words seemed to be his. The whole complexion of the conference changed completely with Chou En-lai’s statement. Nobody could say how the sudden change had been effected. Had orders been issued by someone guiding the supporters of the Western powers? However, it was as if the storm had suddenly subsided and the sun had come out again.

In the political committee, Sir John Kotlewala of Ceylon made a strong statement denouncing the imperialism of Russia in the East European countries. There was another deadlock. The debate opened up again. The conference was split into two irreconcilable groups on colonialism and coexistence. It was a depressing sight to see that the diplomatic efforts which had been made by the Colombo powers, some days prior to the conference, were being wrecked because of personal pique.

After the political committee meeting broke up in the evening, JN had an excited argument with Sir John Kotlewala, PM of Ceylon, which soon deteriorated into a frightful row. JN was angrier than he had ever been. Sir John was defiant and excited.

JN shouted, “But you might have told me you wanted to do this.”

Sir John said loudly, “Do you always tell me, Mr Nehru, what you are going to do?”

It was an agonising moment. Mrs Indira Gandhi held JN’s arm, whispering to him in Hindi to keep calm. But both of them went on like two angry schoolboys, while Chou En-lai tried to soothe Sir John by saying in broken English, “Me, your friend.” All of us stood by silently at this clash of galaxies and the thought came to me that, however great a man might be, however heavy his responsibility, he never ceases to be a human being.

In that difficult situation, JN’s first thought was to go to U Nu. On return to the house, he rang up U Nu and had a long conversation with him.

Feverish diplomatic activity took place that night. JN had a long session with U Nu and Chou En-lai. Krishna Menon flitted about among his UN friends, much to the dislike of Sir John, who, in an ebullient mood, declared that he (Krishna Menon) “deserves to be castrated”.

By the morning, the storm had passed over. Sir John made a dignified statement that he had no intention to disrupt the conference.

Chou En-lai maintained a dignified moderation in all he said, and in moments of crisis, was content to sit back and allow the neutral countries to come to his aid. All his efforts were directed towards allaying fears and encouraging support. He came forward with a dramatic statement that China was prepared to negotiate with the US over the subjects that were causing tension in the Formosa (Taiwan) area.

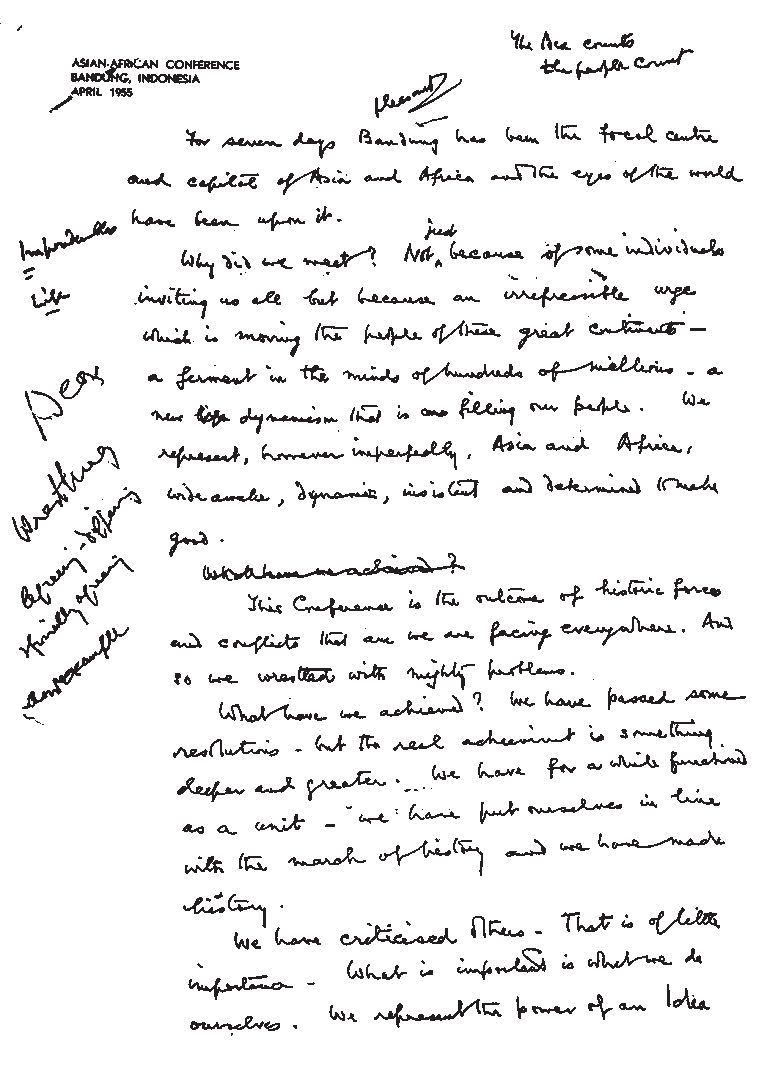

JN made a brilliant speech at the end of the conference; a memorable speech which will be remembered for long by those who heard it. It was the hand of friendship stretched out to all the peoples of the world. The gist of his speech as noted down by him in his own hand reads as follows, though the actual speech delivered by him was slightly different.

“For seven days, Bandung has been the focal centre and capital of Asia and Africa and the eyes of the world have been upon it.

“Why did we meet? Not just because of some individuals inviting us all, but because (of) an irrepressible urge which is moving the people of these great continents—ferment in the minds of hundreds of millions—new dynamism that is filling our people. We represent, however imperfectly, Asia and Africa that is wide awake, dynamic, insistent and determined to make good.

“This conference is the outcome of historic forces and conflicts that we were facing everywhere. And so we wrestled with mighty problems.

“What have we achieved? We have passed some resolutions—but the real achievement is something deeper and greater. We have, for a while, functioned as a unit—we have put ourselves in line with the march of history and we have made history.

“We have criticised others—that is of little importance—what is important is what we do ourselves. We represent the power of an Idea. We have to realise that great Idea in our respective countries—build up our countries on strong moral and material foundations and cooperation with each other.

“This is not a conference against Europe or America. We send the governments and peoples of these continents our greetings. We tell them that we are friendly to them and will cooperate with them as equals. Asia will tolerate no longer the dominions of others or any compulsion.

“Australia and New Zealand are almost in our region and we would particularly welcome cooperation with them.

“If we have given a gentle warning to others, the warning to ourselves is far greater and severer. We have to make good ourselves and rely on ourselves. Thus we will build the new Asia and Africa—free and dynamic and self-reliant and without fear.

(Notes made by the Prime Minister for his speech at the concluding session of the Bandung Conference. The actual speech was very slightly different. Nehru did not depend on the officials of the External Affairs Ministry for drafting his speeches delivered at international conferences.)

“It is this Asia and Africa, no other, that stretches its hand of fellowship to all countries of the world.

“May we prove worthy of our destiny.”

However, after returning from Bandung, JN never liked talking about the conference. Whenever I spoke about Bandung, a cloud gathered over his face. To a man who had never known a setback in his life, the fact that he did not make a success at Bandung (even though the conference was a success mainly due to him) was difficult to forget.

A month or so after our return from Bandung, the Prime Minister went on an official visit to the Soviet Union and other East European countries. He was received with great enthusiasm in these countries. He invited the leaders of these countries to visit India. The Prime Minister of the Soviet Union, Bulganin and the General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party, Krushchev were given a spectacular welcome when they arrived in November 1955. Miles of cheering crowds, gaiety and illuminations, and each man’s desire was that friendship between the two countries would develop beyond the stage of public ovations to leaders.

The man who had given a lead in the reception to the Soviet leaders and removed the carping doubts of politicians and civilians was Nehru. JN, who understood the people and seemed to give expression to their ideas, had lifted it above the ordinary humdrum routine. He had the courage to face those in his party who claimed that hobnobbing with communist leaders would strengthen the CPI. He had the greatness to ignore and ridicule any official adviser, civil or military, who felt that such a dalliance would lead to infatuation or even affection for communism.

On arrival at Calcutta, Bulganin and Krushchev’s drive from the airport to Raj Bhavan was a tortuous one. The streets were full of people and progress was often held up. The tremendous ovation to the Russians had become so overwhelming and emotional that the guests had to be put in a black police van and quietly taken to the Raj Bhavan.

Gopi Handoo, the Indian security officer, attached to the Russians, told me the story. At the airport when the Russian visitors landed, everything went off well as the public had been excluded. The photographers rushed about as usual. The Russians did namaste. From a distance the crowd cheered and the police officers looked apprehensively at the barriers. Then they started for the Raj Bhavan. Dr BC Roy, the Chief Minister, was with Bulganin and Krushchev in the rear and Handoo with Suvarov (the Russian Intelligence Chief) was in the front

Crowds were thick in the outskirts of Calcutta, but when they reached the city, the speed of the motorcade dropped to a crawl. Soon the rear cars were left behind. Even the escort was cut off, and the Mercedez Benz with the guests crawled forward, puffing and blowing. At Central Avenue, the Marwaris (the trader’s community) blocked the route with flowers and socialistic slogans. Flowers rained, quite unlike the gentle dew from heaven. Crowds—jostling, pushing and pulling one another—surrounded the cars to shake hands. Excitedly the people shook hands with the Russians, grabbed and pulled at them, tore their clothes, yelled slogans and shouted and screamed in excitement and joy. Bits of the car were wrenched out. First went the decoration, then the stepneys and the gadgets on mudguards.

The 74-year old Dr Roy pleaded and shouted, and hit the crowds with his hands. Handoo charged and lashed out at them. His glasses were wrenched out. All around was a solid struggling mass of bodies and hands uplifted to hold and catch at whatever could give support.

At that critical juncture, the poor Mercedes that had taken a lot of punishment, conked out and refused to go any further. Dr Roy and Handoo held a quick consultation. A police wireless van, which was standing by the side of the road, was brought up with difficulty, and the Russian guests were transferred to it, and taken away, in purdah (curtain) to Raj Bhavan, while the crowds all along the route held up the rest of the Russian entourage and shook their hands, wondering who was Bulganin and who was Krushchev!

When the crowds eventually noticed that the guests were already inside Raj Bhavan, they became excited, shook the iron gates and threatened to break them down and beat up the one who had deprived them of having a glimpse of the guests.

This, in a truly Indian way, was an historic and unforgettable welcome given to the two Russian visitors, who had stepped out of their country for the first time. The Russians were not very disconcerted. They told KPS Menon (our ambassador to USSR), “It will be something to reminisce about in Moscow.” JN, who flew over to Calcutta the next day to be present for the public reception, said he was rather amused, but added, “If I had been there, this would not have happened.”

The PM’s security officer and prophet of gloom that I was during those days, could only shake my head and feel deep down within me that this was the stuff out of which tragedies were made.

I met the two Russian guests—Bulganin and Krushchev, at lunch that day at Raj Bhavan, and cautiously crept up so that I got a seat next to the interpreter and heard the conversation between JN and the Russian dignitaries.

JN (to both of them, strictly according to protocol): “You have had a busy time since we last met. You must have seen a large number of the people of India. But how many would they be out of the 370 millions of people in our country?”

Krushchev: “We met a very big number of your people. The ovations we got from them were very emotional.”

JN: “Yet, they were a small number compared to the people of India. You can see (he continued with a laugh) that our problem is often as to how to control the affection of the people. At times that becomes more difficult than even their hostility.”

Krushchev: “Yes, you cannot control the emotional feelings of the people.”

Skilfully JN told them not to feel offended at the reception given on their arrival. He was frank, amusing and even slightly apologetic. The Russians, who perhaps might have had doubts, were completely satisfied that there was nothing in the Calcutta reception except an emotional outburst

Krushchev: “Coming into this house in a surreptitious manner reminded us of our early days when we carried on our struggle underground.”

JN: “I must tell you that in this same city I have been taken through the streets in a police van for trial in a court of law. And the funny thing (with a glance at me) was that the policemen who were escorting me were shedding copious tears because they did not like the job they were doing.”

The conversation was not on a high diplomatic level. There were no references to Panch Sheel, the Geneva spirit, Germany or disarmament. The thought occurred to me that in most of these so called diplomatic meetings, more must be said about trivial things than about matters of the moment. In the present time, most diplomatic moves, particularly in democratic countries, occur at public functions, at banquets where speeches are given, or in public meetings as in India, so that the press and the radio can carry them over to the millions and help to build the background from which the policies in a country are formulated.

The public reception at the Calcutta Maidan was a thoughtprovoking sight. There were 20 to 25 lakh people, who had trudged over miles, been held up at countless places, were pushed about by hundreds of policemen and volunteers. Far away, as far as the eye could see, men were present, sitting on the ground, on vehicles, on trees, on anything that they could climb on. To millions of them, the Russians were just indistinguishable dots on the red rostrum. They could neither see them nor hear them. Then what was the reason that had brought these millions of people to the Maidan? It was not the tamasha alone. It was not the holiday that had been declared. It was the irrepressible force of history, which had dragged out millions of men to stand together at a moment that will pass into history.

After, the visit, Nehru remarked, “Again and again they (the Soviet leaders) said that they had to change their opinion about India completely after coming here.”

A significant statement was made by Krushchev during the visit, the seed of which sprouted and bloomed “We do not want to come between you and your friends. In fact, we want to be friends of your friends, which means that we want to be friends with England, America and others.” Nehru felt that the exchange of visits had left an indelible impact on the Soviet leaders.

After forging close ties with China, Soviet Union and countries of the communist bloc, JN went to Saudi Arabia in September 1956. To the people of Saudi Arabia, the PM of India was the man, who, when the Egyptians were threatened with force, boldly spoke up for them and saved the Arabs from foreign occupation. He was a ‘messenger of peace’, the man who had raised the prestige of Asia in the world, and so they gathered in large numbers at the airport to welcome him. A watering truck liberally sprayed precious water on the runway. Inside a bus, the band practiced ‘jana gana mana’. The Saudi princes and the nobles arrived, and their brutish-looking bodyguards spread themselves out.

JN made a nicely worded statement about coming on a pilgrimage to that land. “To your land, millions of people come for pilgrimage every year. I have also come as a pilgrim in search of peace and friendship. I am sure I shall find it in your hearts and minds.”

We were received with much ceremony in the palace of His Majesty King Saud al-Said, the tall, dignified sovereign of Saudi Arabia.

One remark of the PM, which he made in the course of conversation, in the car, with Prince Salman, stands out in my mind. The prince had stated that the Arab world was grateful for the fact that war had been averted. The PM said, “The British feel that the oil installations are vital for them. If they are deprived of oil, they will be stifled. Yet, they don’t realise that it is by their present policy that they would easily lose it.”

We were to stay at Sadia palace—a fantastic palace that had been constructed within a few months, in a small palm-studded gulley, a little outside the city. It had been specially built for the PM of India. The palace looked utterly garish, bizarre and unashamedly expensive. Its carpets were fabulous. Every room was expensively furnished; there was full airconditioning, and massively gilded furniture.

Nehru went into his room with a smile of incredulity on his face. Could this be real? He sat on the enormous bed—admired the massive bottle of lavender that adorned the dressing table, and then asked me to show him how the airconditioning worked so that he could put it off when necessary. In the short time I had with him, I had a brief conversation with JN about the Suez Canal crisis. I mentioned that it seemed that some sort of ultimatum from the British had been delivered to Colonel Nasser, which he had been smarting under and which had caused grave anxiety among the countries of the Arab League. This was not the “information” or “tip-off” of an intelligence officer, but a supposition formulated on the indefinable tenseness that could be observed in Daharan and Riyadh. JN said that it was all a bluff on the part of the British who wanted to make Nasser agree to their terms. I then mentioned to him that the stock of India in the Middle East was fairly high because of his policy and even though Saudi Arabia was an Islamic country, it felt closer to India than to Pakistan.

Karachi’s leading newspapers, Dawn and The Morning News, published editorials castigating Saudi Arabia for according Nehru a great ovation and calling him Rasoul al-Salam (messenger of peace).

Dawn objected to the term Rasoul al-Salam used by the people of Saudi Arabia to hail Nehru. The Saudi Arabian embassy in Karachi explained that Rasoul al-Salam meant ‘messenger of peace’ and not prophet of peace.

The Dawn countered by saying, “Most Muslims in this country know what the literal meaning of the word Rasoul is, but they also know that it has acquired a sacred connotation since the advent of the Holy Prophet whom the kalima specifically describes as Mohammad Ur-Rasoul Allah—Mohammad, the messenger of God. It is more than strange that in the rich vocabulary of the Arabic language, King Saud and his court could not find any other slogan to tell their people to shout in honour of their illustrious visitor from Hindu Bharat. Besides, it is the Prophet of Islam who is looked upon by Muslims throughout the world as the Prophet or messenger of peace, because through him, God propagated Islam, the religion of peace.”

Two months after our return from Saudi Arabia, in November 1956, I was at Palam Airport as the PM was to fly to Hyderabad. A newspaperman opened a paper and showed me:

‘Anglo-French Bombers Attack on Cairo’

JN arrived, tired and sad and rushed into the aircraft. A little before 7.30 am, I told him that the news from BBC was on the air and asked him if he would like to hear it. He went into the crew compartment and put on the earphone. “Dentists all over the world have testified to the efficacious quality of Macleans toothpaste.”

“Is it BBC?” he asked me.

“Its coming... This is Radio Ceylon and it will relay the news from BBC.”

Before I could finish, he flung away the earphones and got up from the co-pilot’s seat. “I am not going to listen to a toothpaste advertisement,” and went back to his seat.

I told him what the news was. It sounded like a war was on—bombing of Cairo and other airports—conflicting reports on landing of troops. Warships were said to be approaching the Suez Canal.

He sat down with a writing-pad on his lap, making notes, with the morning newspapers round him in disorder. When I looked into the cabin again, he was fast asleep. He was obviously very tired. What I marvelled at was that he could sleep at a time like that. A lesser man would have spent his time in worry, in anxiety, criticising himself, preparing for the future, preparing at least for the important statements that he would have to make within a few hours in Hyderabad. JN slept, oblivious of everything.

At a meeting of Congress workers at Hyderabad, JN said, “In all my experience of foreign affairs I have come across no grosser case of naked aggression than what Britain and France are trying to do...”

The attack on Egypt came as a bolt from the blue. I was of the view that in the final analysis whatever Egypt may have suffered, England and France had suffered more and will continue to suffer greatly. They had more to lose than Egypt.

At about the same time, the Anglo-French forces were engaged in hostilities against Egypt and fighting had broken out in Budapest. The situation in Eastern Europe was not clear. JN referred to the events in Poland and Hungary in his speech and hoped that the release of internal pressure would lead to a satisfactory solution of outstanding issues between them and the Soviet Union. Apart from the outward features of the crisis, there was a crisis of conscience, a spiritual crisis almost in the people’s mind.

The events in East Europe have shown that armed forces cannot be used to suppress people, wherever they may be and however they may exist. If that fact is accepted, let us have full freedom, whether it is a communist society or an anti-communist society.

The communist parties in the world are in the process of re-charting their course—the world might yet emerge from the present-day flux to a new crystallisation of powers and states.

JN followed a vigorous foreign policy and tried to bring about peace at the troubled spots. However, at home, the Kashmir issue remained intractable. While flying to Madras in January 1957, JN sat hunched up over a writing pad in the plane. I wondered what he was writing with such deep concentration. He looked very fit and carefree, and the gay laughter of Lady Mountbatten that issued from the compartment showed that they were not talking all the time about international disagreements. Before going to the public meeting in the Island Ground (which was always a big event), JN went through the notes he had prepared and which were the same that he had been working on in the plane. After the meeting was over, I asked him if he could give me the notes. He made no reply. I wondered if I had offended him. The next day, when we were on our way to Poona, he gave me the notes and said, “It’s not all that I said. I couldn’t consult the notes while I was speaking and several ideas came to me which were added.”9 A large part of the speech was devoted to Kashmir, Pakistan and American arms being supplied to Pakistan.

The Kashmir issue started and acquired international dimension in Nehru’s lifetime. He was seized with the problem throughout his term as PM. JN often referred to the Kashmir problem in most of his public speeches and in the Congress sessions. Tracing the history, he stated, “Soon after Independence, we were dragged into war. The people of Kashmir were looted, murdered and made victims of arson. Frantic appeals came from the people of Kashmir, apart from the ruler. It was a difficult decision to take. Fortunately, at that time we had Gandhiji with us. As usual, I went to him for some light

9 I went through The Hindu of 1 February 1957. In those days, the newspaper used to cover the Prime Minister’s speeches in Madras, almost verbatim. I found that the PM had covered all the points that he had noted down for his speeches at the Island Ground and at the centenary celebrations of the Madras University.

and advice. He told me it was our duty to go to the help of the people of Kashmir. He, a man of peace, told us to do this. He did not want non-violence which was a product of fear. He himself was a man who was truly fearless.”

What irked Nehru were the rebukes and exhortations given and the fact that some countries admonished India about moral standards. He noted, “When we refer to facts—to the invasion, rapine, arson, killing and many subsequent happenings—we are asked to ignore them.”

He stated that when the Muslim League flaunted the two-nation theory, the Muslims of Kashmir refused to accept it. They rejected it because throughout history, Kashmir had been a place of very little communal tension. Hindus, Muslims and Buddhists of Kashmir lived together in amity, whether the rulers were Muslims or Hindus. When India was at the height of communal frenzy in August 1947, Kashmir was calm.

He declared, “Out of hatred and violence Pakistan was born and had been fed on that unwholesome fare. We do not want this to spread to Kashmir or India. What pains me is that Pakistani people’s mind is sought to be tied up in this way of violence and hatred against India. I hope they will get over it because we are not going to reply in kind. We will continue to be friendly with them.” He stated that India would certainly stand by all international commitments and shall not breach a single pledge, whatever it might entail. He was pained by the “wild charges of Pakistan, falsehoods, vulgar abuses, bullying and violence.” With the supply of American arms, Pakistan’s attitude had become truculent.

He was amused that Pakistan was demanding plebiscite in Kashmir, when there were no free elections in Pakistan itself or in the Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. Pakistan was being supported in that demand by some countries which, unlike India, had no democracy, free press or freedom of political association.

What disturbed Nehru was that with the continuous supply of armour and aircraft by America to Pakistan, India had to divert funds towards defence, with the result that economic development of India suffered and his favourite dream of “relieving 36 crores of people from want” was not getting fulfilled to the extent he desired.

JN had genuine affection for Sheikh Abdullah. When he went to Srinagar in 1957, he said at the meeting of the National Conference workers, “I did not come to Kashmir for four-and-ahalf years because of the arrest and detention of Sheikh Abdullah. I had my share of responsibility in this action. It was not wrong. It had to be done. And yet it gives me much grief and distress. And when a friend separates from me, I feel sorry. I feel defeated when I lose a friend. I still like Sheikh Saheb and I have often wondered why he took a cause which would have been harmful to Kashmir. When we begin to deal with big problems, we are often confronted by the dilemma whether we should stick to principles or sever friendly ties which have lasted so long.”

I had a conversation with Sheikh Abdullah in 1952, at a dinner party in the house of Yuvraj Karan Singh and his charming wife (one of the handsomest and nicest couple in India). The Sheikh was harassed by doubts. The indecision regarding the future of Kashmir haunted him. He distrusted India. He hated Pakistan. He knew Kashmir was too small to live alone. His doubts kept tormenting him. What will happen? When will Kashmir be allowed to settle down and mould her future? Sheikh Abdullah’s fault was indecision—and after all it was not a big fault, but in the peculiar circumstances of Kashmir, a fault like that could turn Hamlet into a raving maniac.