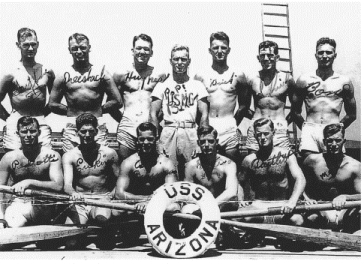

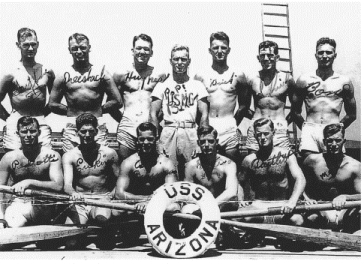

ABOVE: The USS Arizona Whale Boat team in the fall of 1941 in Hawaii. Russ McCurdy is in the front row at far right. Other team members, top row left to right, were Lawrence Griffin, Herbert Dreesbach, Marvin Hughes, John Baker, Eugene Brickley, Gordon Shive, and Burnis Bond. Kneeling, left to right, were Francis Pedrotti, Robert Erskine, Robert Dunnam, Donald Fleetwood, David Bartlett, and McCurdy. This all-Marine team from the Arizona won the play-off races and represented the ship in the fall fleet races. They finished runner-up and lost by only two feet to the Fleet Champions from the USS Pennsylvania. On December 7, 1941, all members of the team except Baker and McCurdy were killed on the Arizona.

I enlisted in the Marine Corps, and after basic training was assigned to the Marine detachment on the USS Arizona. Before December 7, the most notable thing that happened to me was being a member of a really good Whale Boat rowing team that we had on the Arizona. Our team was made up of members of the Marine detachment on the ship, and we started to compete. During the summer of 1941 we entered the Whale Boat competition with the Pacific Fleet.

I was proud to be part of that team, and we did really well in the races, and finished runner-up to the fleet champion team from the USS Pennsylvania. We almost beat them, too, losing by just two feet at the finish line.

A few months later we came up on Sunday, December 7. That morning at 0755 I was getting ready for liberty, getting cleaned up in the forward head. I had just come off the watch at about 0730, and I was getting ready to go into Honolulu to spend the day and have dinner with a local family. So, the first thing was that I felt a small thud like a water barge striking us. Then I felt another thud like that, and I wondered what was going on. I discovered later it was bombs exploding. I went up on deck and there were guys pointing up in the air at planes going overhead, and there were explosions over on Ford Island. Just after that, General Quarters sounded, and then machine-gun fire and our antiaircraft guns came into action. I ran back, and our Marine detachment had a quick muster, then we headed to our battle stations.

My battle station was on the mainmast some eighty-five feet above the water, where I was a gun director for the broadside guns. On the Arizona there were two gun director houses up on tripod masts, one forward, behind the No. 2 Turret, and one just aft of the center of the ship, right in front of the No. 3 Turret. What they called the mainmast was one of the tripod supports for the gun director house above, where I was headed. I followed Second Lieutenant Simonsen, USMC, who was one of our officers, up the ladder on the way to the searchlight platform, when halfway up I saw a large bomb go down into the quarterdeck below us on the starboard side. It exploded and debris flew up toward us. I took cover by leaning back and placing my body behind the tripod leg of the mast, waiting for the fragments and pieces of the ship to whistle past on both sides. The next second or so I proceeded on. Just as I stepped off the ladder onto the searchlight platform, there was Lieutenant Simonsen, and he was badly wounded. He had been right above me climbing up the tripod leg, but he had been hit and his chest riddled by shell fragments and machine-gun bullets. He died right there on the spot, and there was nothing I could do to help him. No one could have helped him.

At that point, it hit me that this was the real thing, and that I was suddenly indoctrinated into war. The attack was in full swing, but I still wasn’t up at my battle station. So I continued climbing on up from the platform, up to the gun director house at the top of the mainmast, and the bombs and machine-gun bullets kept coming all the way up. I finally made it up to my control station where Major Shapley, Sergeant Baker, Corporal Nightingale, Corporal Goodman, Young, and several other Marines were stationed. We had a great vantage point, with full view of the entire harbor. It was a spectacular panorama, almost unreal to watch. The Japanese planes were swooping all around us, and I watched torpedo planes coming in low from across the harbor, heading toward Battleship Row. They’d drop their torpedoes and then pull out so close to us that the planes seemed only an arm’s length away. They were so close, and the pullout speed was so slow, you could read their faces as they slid back their canopies as they went past us. I saw the USS Oklahoma roll over like a wounded, harpooned whale.

Then there was a really violent explosion in the front part of the ship, which caused the old Arizona to toss and shake. First the ship rose, shuddered, and settled down by the bow. This action gave the mast a quivering whiplash effect that turned our control station compartment into a dice box. We were shaken into a human ball, but none of us was injured. Parts of the ship, flames, and bomb fragments flew by us, reaching hundreds of feet into the air. The ship’s midsection opened like a blooming flower, burning white hot from within. Our entire magazine and forward oil storage had exploded; tons of TNT and thousands of gallons of fuel oil poured into the water. Black smoke billowed into the sky as the oil caught fire.

Major Shapley was very calm and assessed the situation like he used to do with our Whale Boat team. Realizing that all director controls were knocked out and the ship was burning, he directed us to head below for further instructions. The wind was in our favor for the risky descent, and was blowing the fire and smoke toward the front of the ship. His calmness and skilled leadership gave me courage to remain calm and alert. We then proceeded down the ladder on the port side tripod leg. The heat was oven temperature, and the flames licked close by at times as the breeze from the after port quarter protected us and kept the fire and smoke blowing forward. The rails on the ladder were hot, and I got some slight burns on my hands as we kept our balance while moving down.

We got to the deck and it was chaos. There were charred bodies everywhere. The passageways were like white-hot furnaces. The wounded and burned were staggering out of the passageways from below, only to die up on deck because of their charred condition. Most were blind, and many had their clothes burned off. I noticed Lieutenant Commander Fuqua trying to comfort many men with his calm and cool manner. For this action and his excellent judgment throughout this ordeal he was awarded the Medal of Honor. One of the ship’s cooks, a man who helped prepare the meals for our Marine Whale Boat team, was leaning against a bulkhead—one leg blown away, leaving just a bloody splintered stump. I saw a terribly burned guy on the deck, and when he spoke I recognized him as my first sergeant. He was lying there on the quarterdeck, burned beyond recognition. The only way I knew him was by his voice. He said, “Marines are Whale Boat champions.” Then Commander Fuqua said to go ashore, and the sergeant said, “Swim for it, champions.” He died a few minutes later en route to the hospital. Just a few minutes before, he had been fully dressed and directing us to our battle stations.

When Commander Fuqua directed the few Marines who survived the blast to swim to shore, Major Shapley and several of us Marines headed for the beach on Ford Island. The major led us through fire, oil, and debris, while bombs were falling and the underwater concussion waves struck us repeatedly. His encouragement guided us all through that swim to a pipeline one-half the distance to shore. While the major was giving words of encouragement to all of us, his strength was weakening, but he still assisted a struggling Marine who was exhausted by his effort to survive. For that, Major Alan Shapley was awarded the Silver Star for saving the life of Earl Nightingale. Now you know why my wife, Pearl, and I named our first child Alan!

I swam from the pipeline to the beach alone, arriving in back of Naval quarters. I headed through the back door of the fenced-in quarters, got inside, and the place was deserted. As I walked through I noticed oatmeal cooking on the stove. Someone had been fixing breakfast and had taken off. I thought, this isn’t good to leave it here like this, so I took it off the stove and turned off the burner. Then I walked back outside and went on to Ford Island Headquarters. And that’s where I stayed until Tuesday night. They first cleaned me up a bit, since I was kind of a mess with a lot of oil all over my hair and clothes, and then I helped with the wounded and assisted at the Armory with the machine-gun posts on top of one of the buildings.

After the attack was over, everyone was still very tense for the rest of the day Sunday, and then there was that awful show of firepower on Sunday night. Everyone started shooting and there was a complete dome of tracer bullets that took down several of our planes.

My only injuries throughout the entire ordeal were slight burns to my palms from the hot railing when I was climbing down the ladder. But my hearing was affected when the Arizona blew up, and my ears were ringing for several weeks. It took many days to remove all the black oil from my hair, nose, eyes, and ears.

A lot of times people ask me, “Were you scared?” And the answer is, “Yes, I was scared!” And you’re thinking, “Will I ever see home again? Will I see my family? How can I get out of this alive?” That’s when you pray a lot and tell yourself to remember your Navy and Marine Corps training, stay calm and try to be like Major Shapley and Commander Fuqua. Those who have seen war carry unforgettable memories of their fellow men, and I will never forget those two and how they conducted themselves and how many other guys, me included, owe their lives to them.

After Pearl Harbor, I went to Marine Barracks, and then I was assigned to the Navy working in downtown Honolulu as a Navy mail carrier. The mail went from the Naval Communication Department in town to Naval Headquarters at Pearl Harbor. After one-and-a-half years, I was selected, along with 200 other Marines, to make up the only all-NCO class to attend officer training and become officers. We graduated 100 percent. I then went overseas and was assigned to the First Marine Division just in time for the Peleliu landing.

I was in the fourth wave coming in on Peleliu. I sat on the front of an amphibious tank taking depth readings to miss the shell holes in the reef as we came in to the beach. That was kind of crazy since I was exposed on the front of the tank, and there were things exploding all around us as we came in; but the machine gunners on the tank were exposed, too, and if we would have gone into one of those shell holes we’d have either drowned or been sitting ducks, and it would have been worse. A little later I was up on the airfield and was sent with a message back to the beach. I had to make it all the way back across the airfield, and it was like a checkerboard with shell holes, and I was under fire the whole way. And it was hot—direct tropical sun and no shade! I drank two canteens just on the way back, going from shell hole to shell hole. I made it out okay from Peleliu and was in the fourth wave on Okinawa and made it through that. I finally ended up in North China. I became a sole survivor when my brother, who was five years older than me, was killed a month before the war was over in Europe.

On December 7, 1941, the only survivors of our fleet runner-up Whale Boat team were Sergeant John Baker and me. Only fifteen out of the eighty-seven-man Marine detachment on the Arizona remained. After Pearl Harbor, my first meeting with Major Shapley was in 1945 on Okinawa, when I was with the First Marine Division and he was a commanding officer of the Fourth Marines, Second Marine Division. We kept in touch after that. Shapley retired as a lieutenant general in 1962.

My first meeting with John Baker was on a small island off Guadalcanal in 1944. It turned out we were in the First Marine Division together. He then was a captain, and I was a lieutenant. We lost touch, and my next contact with him was when I wrote him in April 1974 about an article he wrote showing the 1941 Arizona Whale Boat team. He thought I had been killed on Peleliu, so I informed him I was very much alive! In the meantime, Baker had been informed by Dave Briner of my current address, and Baker wrote me in April 1974 setting the record straight. Our letters crossed in the mail, and he died in June 1974 before my letter was answered. Baker was the coxswain of our Whale Boat team. I maintained contact with Marines Earl Nightingale, Crawford, Cabiness, and Navy men Russ Lott, James William Green, Jim Vlach, John Anderson, and Richard Hauff. Shapley and Baker were Pearl Harbor Survivors Association members along with me, and most of the others I mentioned are also members, and most of us have met every ten years back at Pearl Harbor since 1966. Shapley died in 1973. James William Green died February 22, 1996, and his cremated remains were placed in USS Arizona on December 7, 1996.

I’ve had a lot of close calls and survived them all so far. I should have been killed on the Arizona on December 7, but I somehow made it through that. I was under fire at Peleliu and Okinawa and probably should have been killed a number of times at those places. And since the war I’ve had several heart surgeries and cancer, and I’m still alive. I’ve got good doctors! And I’m proud to report that at the fifty-fifth anniversary ceremony at Pearl Harbor, we had eleven Arizona survivors in attendance, including me.