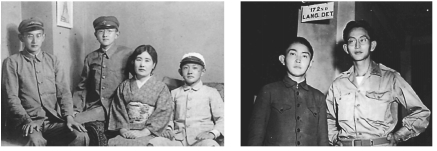

OPPOSITE LEFT: Members of the Fukuhara family in Hiroshima in 1937, from left, Harry (age 17), Pierce (age 15), their mother Kinu, and Frank (age 13). Older brother Victor (age 23) had already been drafted into the Japanese army and was serving in Manchuria. Victor returned to Hiroshima by August of 1945, was exposed to the atomic bomb blast, and later died from the effects of radiation.

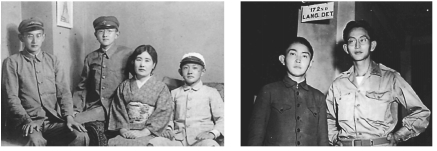

OPPOSITE RIGHT: TWO of the Fukuhara brothers in Kobe, Japan, October, 1945, Frank (age 21) and Harry (age 25) at the 172nd Language Detachment, 33rd Infantry Division

If you can, picture standing on the platform of the Hiroshima city railroad station in early October 1945. That’s where I was on the morning of October 2. I was probably one of the earliest members of the U.S. Occupation Forces to see Hiroshima after the atomic bomb had been dropped. I couldn’t believe what I saw. But I was there unofficially. I had driven twenty-four hours continuously from Kobe to get there on a personal mission to find my family if they were still alive. But to understand why I was there, I must explain my background.

I was born in Seattle, Washington, in 1920. My parents were Japanese who had immigrated to the U.S. from Hiroshima. My father died in 1933 from a prolonged illness. That same year, my mother took the family, three brothers and a sister, back to her home, to Hiroshima. I didn’t want to go. I was thirteen years old, I didn’t speak Japanese, and I was leaving the U.S., the only home I knew. I came back to the U.S. almost as quickly as I could, right after I graduated from high school in Hiroshima in 1938. I was working my way through college in Los Angeles as a houseboy and gardener. That is what I was doing when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

I was interned along with more than 100,000 other Japanese and Japanese-Americans. I was shipped to the Gila River Internment Camp in Arizona. In November 1942, I volunteered from Gila River for the U.S. Army. I trained at the Military Language School at Camp Savage, Minnesota. You are probably wondering why I volunteered for the Army after having experienced mistreatment and incarceration by the American public and the government. People ask me that all the time. As time has passed and I reflect back on what I have learned and experienced, some of my feelings and impressions have changed. But some of the basic beliefs and feelings have remained the same. So let me try and explain this.

I was one of twenty-six Niseis who volunteered from Gila River Internment Camp on November 23,1942. I’m sure we all had our different reasons because of different backgrounds. But what we shared, although we didn’t say so openly, was our strong feeling of patriotism and loyalty to our country. Some of us were Kibeis, born in the U.S. and raised in Japan. We had lived in both countries and were able to compare. Being of Japanese descent, we had an even stronger desire to prove our allegiance to this country, and that was prevalent among all of us who were volunteers. But this was not a universal feeling in the camp. I volunteered when it was not the popular thing to do from within the confines of an internment camp. But I felt strongly that it was the time when I must make a decision for better or for worse, and to back up my decision with action. Some Isseis, first-generation Japanese immigrants, thought I should know better because I had lived in Japan. But I never regretted joining the Army, although there were times during the war that I wished I were somewhere else!

The day Pearl Harbor was bombed, the woman I gardened for fired me on the spot. A neighborhood store owner refused to sell my sister and me groceries. He said he didn’t want “Jap business.” My Caucasian neighbors turned me in as a curfew violator and said they were doing their patriotic duty. These are the types of things we faced after Pearl Harbor.

The popular saying during that time was, “A good Jap is a dead Jap.” Nothing good or favorable was said about Niseis, us second-generation Japanese-Americans, despite the fact that we were born American, ate hot dogs, played baseball, and celebrated the Fourth of July. But our citizenship was ignored, our inalienable rights violated, and we were interned. With the help of the American media, we became bad Japanese, not good Americans. Maybe if there had been more Asian-American journalists, public opinion would not have reached such levels of hysteria.

However, during this very difficult time, two things affirmed my belief in this country—the U.S. military and an elderly couple, Mr. and Mrs. Clyde and Florence Mount. I was the Mounts’ houseboy, and I could have been considered as just an employee. But they offered to help me avoid internment by adopting me or providing refuge in their Ohio family home. Unfortunately that didn’t work out, and I went into the camp. But they drove hours to visit me, defying public sentiment and using precious rationed gas. When I went into the Army, they displayed a star in their window, which at that time signified that a member of their household was serving in the U.S. military. They really took me in as one of their own.

And in a way it was that way with the military. It was not really a very democratic environment, but we encountered very little of intended discrimination, at least nothing like what we had experienced on the outside. As Military Intelligence Service soldiers, we were treated with respect and dignity. The U.S. Army needed us, and we rose to the challenge. We were doing work that nobody else could do, coaxing valuable information from prisoners that could save American lives. Our mission was to serve as interpreters, interrogators, and translators with combat units fighting against the Japanese Imperial Army. We were Nisei Army linguist soldiers trained to use our Japanese language capabilities to support our fighting forces by providing timely and useful information against an enemy we knew very little about.

I ended up in the Pacific for almost two-and-a-half years, starting from Australia and participating in General MacArthur’s island-hopping strategy to return to the Philippines. I took part in three enemy landings and five military operations in New Britain, New Guinea, Morotai, and Luzon. I suffered from battle fatigue and was hospitalized several times with malaria. By the end of the war I was physically and emotionally exhausted. In August of 1945 I was on the island of Luzon in the Philippines. My unit, the U.S. Thirty-third Infantry Division, had successfully taken Baguio City. We had returned to the lowlands to regroup, retrain, and prepare for the final showdown. This was going to be a really fearsome assault on Japan, a massive amphibious landing that would have dwarfed the Normandy invasion. It would have literally turned the tide red with blood.

But then I heard the atomic bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima. I am often asked how I felt when I heard the bomb had been dropped on the city where my family was living. At first it didn’t have much meaning. Like other soldiers, I had never heard of an atomic bomb. I knew nothing about it. But each day more information was disseminated, and I found out more. One of my duties was to explain to the Japanese POWS what had happened. I told them that a new bomb called the atomic bomb, equivalent to thousands of tons of TNT, had been dropped on Hiroshima on August 6 and that one single explosion had completely wiped out the entire city of Hiroshima and that it had been erased from the surface of the earth. I told them no living thing had survived and that all human and animal life were nonexistent. I also told them that no vegetation, plant life, or trees, would grow there, and people would not be able to live there for at least 100 years due to radiation. When I told them that, they just sat there, totally silent. Either they did not believe me or else the information was beyond their comprehension. To tell you the truth I didn’t want to believe it myself.

For the first few days I kept thinking, why? Why did they drop it on Hiroshima? There were other better targets, such as Tokyo, Yokohama, and Osaka. Then I tried to rationalize that my mother had probably moved out and was living with relatives in the countryside where it would be safer and food more plentiful. I figured my brothers would be away from home attending college or drafted into the Japanese army. But my thoughts returned to the original assumption, that if they were in Hiroshima they could not have survived the blast. The more I thought about it, the more depressed I became. My thinking degraded to the point that I blamed myself—that they had died because I had volunteered to fight against them.

Shortly after that I was given the choice of going home or going to Japan with the Thirty-third Division as part of the Occupation. This was a very difficult decision for me—I was torn. I was afraid that it would be futile to look for my family, and that whatever I found would make me very bitter. But I decided that I needed to go, and so I signed up for the Occupation.

I arrived in Japan in mid-September 1945. I had explained the situation to my division commander, Major General Clarkson, and he gave me permission to go to Hiroshima. My Jeep driver and I finally made it to Hiroshima after three attempts. My driver was a nineteen-year-old young soldier from Michigan. He was blond, blue-eyed, and about 6 feet 3 inches tall. He was scared because we had passed through areas where our military had not yet traveled and villages where returning Japanese soldiers were drunk and wild. When we went into police stations and railroad stations to ask our way, I told him to act like an officer and I would be his interpreter. After all that driving, almost twenty-four hours straight, we finally reached the outskirts of Hiroshima just as dawn was breaking. We made our way into the ruined city to Hiroshima city railroad station platform. I was astounded at what I saw. I could see all the way across to the other side of the city, a distance of several miles. It was eerie and lifeless. There was no movement or noise.

After a while I saw a few men around bonfires. When I asked for directions, they acted like zombies and did not even look up to see who was talking to them. I thought they were the only ones who had survived.

Finally we found the house where I had lived seven years before. I told the driver to stay with the Jeep, but he didn’t want to be left alone. The two of us, he armed with a rifle and me with my .45-caliber pistol, knocked on the door of my house. It seemed like a long time when finally two emaciated-looking elderly women appeared at the door. It was my mother and my aunt, but neither said a word. They just stared at the tall soldier standing next to me. I had rehearsed what I was going to say, but when they both stood there looking scared I just said, “Mom, I’m home” in Japanese. My aunt recognized me before my mother did. When she did, she broke down. Her first words that tumbled out were, “What are you doing here? How did you get here? Where did you come from?” We were finally welcomed into the house.

When we went in I noticed the splintered glass embedded in the walls. The back of the house, facing the epicenter of where the bomb exploded, was etched with the shadows of the trees and shrubs that themselves had been scorched into skeletons. My older brother, Victor, was lying on the floor upstairs. My mother told me he had been on his way to work when the bomb went off. He was dying but I did not know it then. My mother said he had showed up several days after the bombing. He had difficulty talking and could not recall what had happened. I tried to get him hospitalized in Hiroshima, but there was no room. I had him moved to Kobe where I was stationed, but he died within a year.

My two brothers, Pierce and Frank, had just returned home a few days before my arrival. Both had been drafted into the Japanese army. I found out years later that both had been assigned to suicide units near the beach where my Thirty-third Division was supposed to have landed on Kyushu, as part of the final invasion that was to end the war in the Pacific. Only Truman’s decision to drop the atomic bomb had avoided all that bloodshed.

Looking back on it now, sometimes I think it was fortuitous. My older brother died from the atomic bomb, but my two younger brothers, both Japanese soldiers, and myself, an American soldier, are alive today because of it. Plus my mother. One life for four. Maybe they were not bad odds amid the misfortunes of a great war.

For years, by virtue of a silent mutual agreement, we avoided talking about what happened to our family in Hiroshima. The only balm for the tragedy has been time—a full half-century and more. It’s been that long since my brother died, and nearly thirty-five years since my mother died. Until she died she was plagued by unexplainable illnesses. I can talk about what happened in Hiroshima now, more than half a century later. I believe that talking about it now, with a purpose, is the medicine I need.