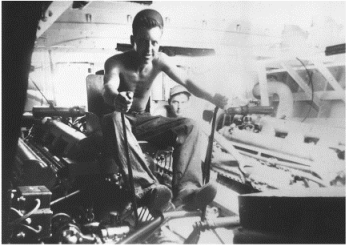

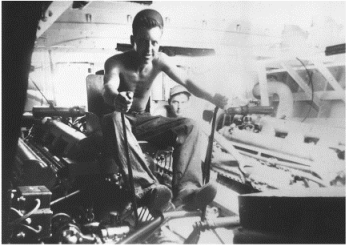

ABOVE: Al Hahn in the engine room of PT 161 in the Philippines in early 1945. Two of the three Packard V-12 engines are visible in this photo. Al controls the clutch levers that engage the engines on commands from the skipper in the cockpit just above the engine room on the main deck.

I heard about Pearl Harbor when I was in Longmont, Colorado, and I was working for a doctor there. I was over at one of his neighbors, and he said, “Say, did you hear what happened to the United States naval fleet?” “No, I didn’t hear a thing.” And he said, “The Japanese bombed them at Pearl Harbor.” “Pearl Harbor,” I said, “where is that? Never heard of it.” “Well,” he said, “that’s a naval base in the Pacific.” “Well,” I said, “Why did they do that?” Well, of course, he didn’t know. We decided that they kind of wanted to declare war on the United States. I was a senior in high school at that time; I had four or five months to go before I graduated, and that’s the way I heard about the United States getting into war and about Pearl Harbor. Then I went to school the next day, and they had a big assembly and talked about it a little bit, and by this time I think Congress had declared war on Japan. That’s how I got acquainted with it.

I had to finish high school first before I could enlist, and so I did. While I was in high school I was taking a course to learn how to be a machinist. During the month of May they sold the entire machine shop to the government, so that ended my classes. I lacked about two weeks, but the teacher said, “Oh, well, that’s good enough. You just about completed it.” I kind of liked it and wanted to pursue that and learn a little bit more, so I got a job working at the Silver Engineering Works in Denver. I worked there until October 1942, but then I decided that there was too much excitement going on in the world to keep working in a defense plant during the entire war. So a neighbor kid and I, we both graduated together, we decided we were going to enlist. So we did, we joined the Navy.

I’d never even seen the ocean. So this friend of mine and I, we both joined the Navy, joined together. We left Denver in, let’s see, we joined in November of ‘42, then we headed up to Idaho—Farragut, Idaho. We went through boot camp in Farragut. Everybody used to talk about all of the terrible things at boot camp, but I thought it was like a vacation! I enjoyed it, you know, I just thought it was a good place to live, lots of friends, good food, and there’s always something to do and a lot of excitement and everything. I couldn’t see anything wrong with boot camp.

The recruiting officer had said, “Okay, you want to be a machinist. We can just work that out and you can go to a machinist school.” So I applied for a machinist school, but I think that the people who were assigning all of this stuff, they didn’t know the difference between a machinist and a motor machinist. Well, there’s a world of difference between them, but they sent me to a motor machinist school, and then I went to Ames, Iowa, to Iowa State University.

When I went to high school I was a very poor student. I didn’t have the slightest interest in school. I was interested in all kinds of other things, but school was not one of them. I did so poorly, you know, I graduated at the bottom of my class. Maybe not the very, very bottom, but close to it. But anyhow, when I got to Ames, Iowa, they had a sort of motivational factor that if you graduated within the top 10 percent you could get an advancement. I got to thinking, you know, I didn’t think I was really as dumb as my high school record indicated. I thought, I’m gonna shoot for it, see if I can get in the top 10 percent. So I knuckled down and studied pretty good, and I graduated sixth out of 120 guys. I was number six! So I was in the top 10 percent real easy and I got my rate that I was looking for. Then at the same time they were having a recruiting session for PT boat personnel, and they only took guys that had a good record. They said if they were in the upper 10 percent, or something like that, they could apply for PT boats if they wanted to. It was all voluntary. Of course, I was just beginning, so I didn’t really know what a PT boat was, but we talked around on campus there and different people began to tell me that they were a pretty nice little boat. They were fast, and they do this and that and everything, and the more we talked the more interested I got. So I decided I was going to apply for that, and I did. I applied for it and I got it. Then I went to Melville, Rhode Island.

There at Melville we began to study aircraft engines, because that’s what they had, Packard V12s. While I was in Ames, Iowa, we were studying diesels. That meant that what I learned in Ames was okay for the principle of the thing, but it didn’t specify the details or even the difference between a diesel and an aircraft engine. We were trained to be familiar with all the other parts of the PT boat. You would have to become familiar with the entire boat, but that was more as a matter of generality. For example, we all had to learn how to drive the boat.

We really became pretty much like a family on our boat, officers and enlisted men. The only real difference was the officers knew what was going on most of the time, and the rest of the crew didn’t know anything! They’d say, “Well, there’s no need for you to bother yourself with all of this kind of stuff.” What I’m really saying is, especially when we got into the war zone and they were planning strategy, they would go up to the headquarters and get briefed on what they were going to do, and they’d come back to the boat and they never told us anything. They’d just say, “Well, we’re going on a mission tonight. Everything ready?” You know, that was really the only difference between them and the enlisted men, because most of the time the officers were just part of the gang.

The skipper who ran the boat was a first lieutenant, and there were two officers on each boat. We’d usually have an ensign and a lieutenant (j.g.). The boat is built for twelve more or less. I was on a Higgins boat in the Mediterranean and an Elco boat in the Pacific, and there were about twelve of us, but that varied a little bit. Sometimes we’d take on a couple of extra personnel, like during an invasion.

We slept on the boat all the time. The enlisted men were sleeping in one area and the officers were in another area. The enlisted men slept in the very bow of the boat, except where the bow comes to a point. We had what we called a locker there that we threw all our sea bags and stuff in, just threw them in and filled it up. Then right behind that there was room for twelve people in there, and then behind that was a chart room, chart house, and the officers’ quarters were right underneath that. They just had a little bitty spot, just for two people. It was about like an ordinary bathroom in a house.

We had a bathroom, but it was so tiny that we only used it in extreme emergencies! Most generally when we’d go out on patrol we went out at night, and in the morning we’d come in. We were always tied up at a dock at the PT base, and at the base they’d have a chow hall and showers, a bathroom and those facilities, and this is what we used except for sleeping. When we’d come in off of a patrol, we’d eat breakfast at the base. Then usually the next thing for me to do would be to fuel the boat. We’d fill her back up so we had 2,000 gallons of 100-octane gasoline. The refueling area wasn’t real close to our dock. For safety purposes they kept it maybe like a quarter of a mile away. We’d go over there and fill her up. That was my job. I was down in the engine room all the time. The engine controls, like engaging the clutches and throttles, were run by hand by me. On the Elco boat in the Pacific I had a seat right on top of one of the three engines, and there were long handles for clutches to engage the engines. At minimum it would take two of us, one in the engine room and one at the wheel up on deck, to really drive the boat. I was just about always in the engine room, and I was looking at an instrument panel in front of me that relayed instructions from the skipper on the bridge right above. You not only had instruments that’d tell you what each engine was doing in several different categories, but also signals from the bridge about, you know, forward, reverse throttles, and so forth. We had throttles down there and they had throttles up above, and it was kind of a combination right there.

First I was assigned to the Mediterranean on a Higgins PT boat, and we saw a lot of action, and we had a lot of our guys hit. Every one of our crew got wounded except two, and of the two who didn’t get wounded one was our executive officer and the other was me!

In October of ‘44 I came home for a leave, a long one. Then I went back to Boston, and it was in December that I got word I was getting shipped out to the Pacific. I left Boston and I think it took us five days by train to go to San Francisco, and there I got on the Matsonia. It was a luxury liner in peacetime, but they converted it to a troop ship. It was a nice ship and all that, but it wasn’t much like a luxury cruise or anything. It was pretty well crowded, but they had a lot of nurses on a different deck up above. Of course they’d stay there in their quarters and we stayed in ours. At least I didn’t see any hanky panky going on, but we were enlisted men anyway and that was out of the question since the nurses were officers. There was, well, what you might call speculation about those nurses, but I don’t think anything ever happened! Anyhow, we dropped them off in Hawaii, at Honolulu.

Then we went to New Guinea. When we crossed the equator, they had what they called a Neptune Party. This was to initiate those of us who had never crossed the equator before. The ones who had gone through this before were called Shellbacks, and those of us who hadn’t were called Pollywogs. Unfortunately for me, I was in a cabin with mostly Shellbacks. In fact, most of the guys on that ship were Shellbacks, so they really had it in for us Pollywogs. The first thing that happened was they stripped us naked and had us crawl through a gauntlet, which was a long line of guys on each side, and it was a swat line. Each one of those guys had a wooden slat they had pried off some packing crates. So as we crawled down through this double line, these guys were beating us on the butt. That was bad enough, but what made it really difficult was that at the end of the line were a few guys with a fire hose, and they were spraying that thing full force at us as we tried to crawl out of this line. So that meant it was a struggle to just get through the line, and all the time we were getting beaten with these wooden slats. I couldn’t sit down for a week!

For some of the Pollywogs, they blindfolded them and had them walk the plank, which was a board out over a tub filled with water, but they thought they were walking a plank out over the side of the ship into the ocean since they couldn’t see. They’d scream and holler when they went over that plank and hit the tub of water, and thrashed around thinking they were in the ocean. But when they got the blindfolds off they saw they were still on deck, and all the Shellbacks really laughed at that. I was lucky and didn’t have to do that. After this was all over we got issued Shellback cards, and I carried mine in my wallet for years. You never want to lose it, so in case you cross the equator again you don’t have to go through another initiation. Right now my Shellback card is in a safety deposit box!

So we finally got to a place called Hollandia on the north coast of New Guinea. I was there for just a little while, oh, maybe a week. Then by this time I was already assigned to a PT boat squadron, to squadron nine. From Hollandia they took us up to Samar near Leyte in the central Philippines. It was a brand-new base, and it was a main PT boat base for the Philippines.

From there I got assigned to PT-161, and that was the boat I rode in the Pacific all of the time I was there. I was probably the second or third replacement “motor mac” for that boat because that was such an older organization. The original crew, they probably weren’t even in the Navy anymore by the time I got there.

I was maybe a little apprehensive of moving in with that crew because I was just a new guy on their boat. But I got a pretty warm reception because I already had this experience in the Mediterranean, and everybody was pretty curious to know what was going on in the Mediterranean. So by the time I told them a few of those stories, well I was one of the gang.

It took me about five minutes to make the transition from the Higgins PT boat I was on in the Mediterranean to the Elco boat in the Pacific. I mean, they’re basically the same, maybe a little different arrangement, but you pick that up in a minute or two. I was based on an island off of Mindanao called Basilan. It’s about twenty miles from Zamboanga. Actually it was a little island off of the island of Basilan. Just a little tiny one. You know a big ocean wave could roll over the top of it, so that was where we were based.

We’d trade little things with the Filipinos, cartons of cigarettes or something. Actually this friend of mine and I, we bought a boat. It was one of those dugout canoes, a double outrigger. I think we bought it for a carton of cigarettes and a couple of t-shirts and a pair of dungarees; I think that was about all we paid for this boat. It was a brand-new one, just carved out, a beautiful little boat. We got it and we used to sail it around when we had days off. But when I went off to the invasion of Borneo, one of the base force guys got it, and he used to sail it over to Isabella Island, you know, and get to drinking sake. His squadron commander wanted to put a stop to that, so he burned our boat while we were gone. All we could see when we got back was a little pile of ashes! That really upset us, but there was nothing we could do about it.

Well, I’ll tell you, in the Pacific I didn’t see as much action as I did in the Mediterranean. The only activity I really saw in the Pacific was during the invasion of Borneo. It was probably in February of 1945. Our job during that invasion was first of all to patrol the area, and if we possibly could we’d shoot up things like petroleum storage. If we saw any gas tanks and stuff like that we were supposed to blow them up. And we did blow a few of them up. The only real enemy engagement that I experienced at that time was when we were sent to shoot up a Japanese army camp up one of these big rivers. I guess it was someplace between five and eight miles up the river in Borneo. I don’t even know the name of the river. Nobody was ever worried about whether I knew any of this stuff or not; they just said this is where we’re going. We had some native guides and they would sit on the bow of the boat with their feet hanging over the end. They would point toward the deepest part of that river, this way or that way, and we kept on going. We had another boat right behind us. We got up there and sure enough there was this big Japanese army camp, and the plan was that we were supposed to surprise them, shoot for maybe two minutes with all our guns, and then get out of there. On each boat we had one 40mm, one 37mm, two sets of twin 50s, two sets of twin 30s, and that’s a lot of firepower right there. Then you multiply that by two because there was another boat right behind us. When we first went in there, we quick turned around in the river so we were headed in the right direction to make a getaway. Then we fired away just like we were supposed to. Finally we figured, well, we did as much damage as we can, and we’re going to take off.

So we took off, our boat did, and wham, some of the Japanese were still sitting behind their machine guns, and they hit the other boat right there down by the engine room. They put 50 or 100 holes in it, and anyhow their engines conked out on them. I never could figure out how they could conk out all three of them, but they did. We got this urgent call on the radio that they’re dead in the water, and they were yelling, “Come and get us.” Well, you know, we didn’t really like that kind of an assignment, but okay, here we come. We turned around in the river and we went back. But now you have to keep all the Japanese away from their guns; they didn’t return fire very much as long as you were firing. They were ducking for cover. We pulled up and were firing, and the other boat still had their guns going. The engines were dead but the guns were still okay. So they are firing and we are firing all the time, and we had to turn around again in the river to rig a tow. We tied a line onto the other boat and started to take off. Well, we were in such a big hurry we kind of gunned it a little too much and snapped the line. Well, it takes a long time to stop, go back, turn around, tie on again, and all the time we had to keep these guns going.

By this time though we started running out of ammunition. We had a lot of ammunition down in the bottom of the boat, but up there on deck where the guns were, they were empty. About half the crew had to give up their gun positions and start moving their ammunition up, and this darn ammunition was heavy. They were pushing it up, and pretty soon their arms were getting played out. They just ran out of power. They were yelling, “We need some fresh help.” What they were thinking of doing was taking some of the guys that had been shooting, putting them down, and taking these guys that were lifting and put them behind the guns, and this executive officer said, “By golly, let’s get Hahn up here; he could push some of that ammunition up for you.” He called the engine room and sent another engineer down there who was all exhausted. He said I was supposed to go up there on the deck and he was going to be in the engine room. So I went up there and I wanted to know what I was supposed to do. The exec said, “Get down there and start pumping up this ammunition.” Well, just about the time I was ready to jump down there, here comes a gunner’s mate off of the 40mm. He said, “I can’t fire the 40mm anymore. It’s too hot. It’s gonna blow up.” And the exec said, “Well, what’s the difference? If you don’t fire it, the Japanese are going to be killing you, so you might as well die right behind the gun no matter how hot it is.” Well, this guy was kind of panicking. I don’t know what to tell you, but he just fell apart. So the skipper said to him, “Get down there and push up this ammunition.” So he sent him down there and he asked me, “Can you fire the 40mm?” I said, “I’ve never fired it, but I know how.” So he put me on the 40mm. That’s the only time I fired a gun in the entire Navy.

I wasn’t worried whether the gun would blowup or not. There was just too much going on around there to even think about it. As fast as they’d bring this ammunition up, well, I’d empty it. All I know is when we were shooting out there we knocked down about all of the coconut trees that were in this area. You know there were a lot of coconut trees standing there, but that 40mm, if you hit a coconut tree it was a goner. The trigger was on the right foot pedal. It took two guys to fire it; one guy, he would aim it in the right direction, and the other guy would aim it up and down. I did the up-and-down and I had the trigger. You’d just push that lever down with your foot and it would fire. There were all these tents and everything around there in that camp, and I could see what I was shooting at real well. With this 40mm you’d have sights on it and you’d pretty much go by the sights. When you put a clip in, a clip had four shells in it, and you could shoot all four shells in two seconds if you wanted to. It was kind of like bang… bang… bang… bang. You know, maybe one shell every two seconds. Something like that, because somebody had to feed ‘em into it. It took two guys to feed ‘em in—if they had all the shells there. We had to wait until they brought them up from the locker, so you have to go a little slower. We really shot up the place. I could see my shells hitting and exploding and dirt and debris would fly, and we hit a lot of things.

The guns were so hot that as soon as the shell went in there it went off. In about half a second it would heat up and explode. Most of that stuff is kind of like a blur because we were all firing as fast as we could. Finally we got the second tow rigged and pulled them out of there and back around a bend in the river so we could quit shooting. Nobody on either boat got hurt; well, I shouldn’t say nobody, since we had one guy who collected the Purple Heart for this: On the way out, this guy had a Thompson submachine gun, and he was out shooting it too. Well, that was just about as effective as shooting little BBs! But anyhow, that’s what he was doing, he was standing up there on the deck firing that thing, and one of the Japanese shot and hit him. He thought he was shot clear through the neck. What happened was when he was shot he grabbed his neck and looked at his hand and he saw all this blood and he passed out!

Because too much other stuff was going on nobody had time to mess with him until we got around the bend and back down the river a ways. Then they looked him over and said, “Well, what’s the matter with you?” He kind of came to and said he was shot through the neck. They looked at his neck, and there was a little blood there. They wiped the blood off and the skin was barely broken, there was just a little scratch there, and it didn’t look too bad. So they told him he wasn’t shot through the neck at all. So he said, “Well, where’s all this blood coming from?” They looked closer, and it turns out he was shot through his ring finger. When the bullet hit his finger, it knocked his hand back. The force of the bullet was so hard that his hand came off the Thompson and he hit himself on the neck with his own hand. The force of his hand hitting his neck was kind of painful there, and he thought he was shot through the neck. So his finger was bleeding, and when his hand hit his neck his fingernail scratched the skin a little bit, see? So they were all laughing and told him he didn’t have any hole in his neck; the problem was his finger! Well, he looked at that and thought that’s not too serious. Then he was okay. But he got a Purple Heart for that. I was up on deck shooting the gun and saw him go down, but I was watching the boat behind us and hoping the towline wouldn’t break again. So even though all this firing was going on, they were still shooting back, there were still some of them popping bullets back at us.

One day the guys on my crew were telling about what happened to them in the days gone back. They mentioned this one officer, they called him a ninety-day wonder, from back east, one of those wealthy families. I don’t know if anybody knew his name or not; I didn’t recognize the name or anything. They told about this guy going off on his own and getting his boat cut in two, jeopardizing the life of the crew, even one or two guys were killed on account of that. Then after I came home and got married, and about fifteen years later, why, there’s this guy running for president, and come to find out he used to be on PT boats. I found out his was the boat that was cut in two, and I finally put it all together that this was old John Kennedy!

The 157 boat was the one that had picked Kennedy up, and it ended up in the Philippines where I was. People knew the story and that the 157 had picked up him and the surviving members of his crew. I got a picture of it. That was a pretty old boat by then because it would have been in the Solomon Islands right at the beginning of the war. Those boats saw activity at different places, and it would have been a three-year-old boat by that time. And my boat, the 161, was the same age. But really, even though we were in the tropics, the boats stayed in surprisingly good shape, though there was quite a bit of mildew. We’d be assigned to a base right next to a jungle or something, and there were a lot of insects flying around at night. Whenever possible we’d go out and anchor maybe a half a mile or a quarter mile away from the shore and there were no insects. Then we’d sleep on the boat down in our berths below decks. You’d think it would be too hot to sleep down there, but surprisingly, around the equator, it wasn’t as hot as I thought it might be. I don’t know why it is, and there was high humidity too, but we were always close to the water. I think that the ocean itself, if you’re near the surface, it has a cooling effect, and I never really suffered from the heat down there around the equator.

Towards the end of the war our job was to go through the islands and pickup all of these prisoners. They had isolated these prisoners on these islands. The Japanese couldn’t get to them and these guys couldn’t escape, so they were just prisoners on the islands without anybody to guard them. They were hard up for food and medical and all of that. We would just gather them up and take them to Zamboanga.

About this time the war ended, and the way we found out about it was kind of amusing. The way it was, see, all the PT boats have a policy that when a crew leaves a boat there’s supposed to be two people to stay aboard. One of them has to know how to handle the ship, as far as the steering mechanism goes, and the other one has to be the engineer who knows how to start the engines, put them in gear, all that stuff. This one particular night we were over in this little town of Isabella off of BasilIon. We just went there about a day earlier, and we were supposed to get three brand-new engines in our boat. Our engines had so many hours on them that it was time to replace them. We were getting ready for the invasion of Japan, which I heard at one time was supposed to take place maybe in November or December. So we went up there and took all the bolts off of the engine room hatch covers. The next day we were supposed to lift that hatch up; you needed a crane to do that because it was pretty heavy. Then that would expose all the engines, and we could remove them and put the new ones in.

So evening came and the crew wanted to see some movies, so okay, who’s gonna stay aboard? Well, I don’t know whether I volunteered or whether it was my turn, but anyhow, I stayed aboard to be the engineer on the boat, and our radioman, he was going to be the guy who knew how to pull the boat out from the dock if necessary—emergency stuff. So the rest of the crew headed to the movies, and we stayed there on the boat and wanted to listen to the radio. I never could hear those darn radios, there was so much static and stuff, but him being a radioman, he was able to pick up the radio broadcasts a little better. We were just kind of hanging around on the boat, and he was down there fiddling around on the radio. Then he pokes his head up on deck and says, “Say, you know, I’ve been picking up some news and it kind of sounds like the war might be over.” “Well, what happened?” I said. This was a complete surprise. We’re getting ready for an invasion, and here you hear the war is over. So he said, “I’m gonna tune in a couple more different frequencies and see if I can pickup something else.” Well, pretty soon he stopped and said, “You know, the United States set off a couple of very strange and very powerful bombs. They dropped them over in some places in Japan and killed a lot of people. It’s a kind of a bomb that we had never used before.” So I said, “Well, what kind of a bomb is that?” And he said, “I don’t know but it’s supposed to be very, very powerful. I’m gonna keep listening.” So pretty soon he came back up and said, “There’s more reports and excitement out there that the war is over.”

And we were looking down about a mile away, and we could see some tracer bullets going in the air. That was our old base where we normally would be. We figured they must have discovered this too and were celebrating by shooting their guns in the air. So we were wondering how we were going to let the other guys from our crew know the war was over. We couldn’t go get them because we had to stay on board, and they were over at the movies. This was at an outdoor theater, which really wasn’t a theater at all, just a sheet hung up from the trees. So he said, “I know what we can do. We have a mortar, so let’s set it up and get their attention.” I didn’t know how to set it up. I wasn’t acquainted with that stuff, being an engineer. But he got that mortar and he got a plate that went on the deck and everything, and then he got out the star shells. He started dropping them in this mortar. They’d go up and explode right over the guys who were watching the movie a ways away, and it was like the Fourth of July; these star shells went off like fireworks and lit up everything. So the guys on our crew couldn’t understand what on earth happened to us. They thought we lost our mind. They came running back, thinking we were under attack or something, and they were yelling, “Hey, what’s the big idea?” So we told them, “The war is over!”

Then the celebrations began. The next day I noticed our quartermaster was running a new flag up on the flag mast because the old ones get so tattered from being whipped around in the wind. I thought I’d like to have a souvenir of this event, and I asked him. I said, “You’ve got some more of these flags on stock down there?” “Yeah,” he said, he had a little supply. I said, “That’s the one I want because that was flying on our boat the day the war ended. I want to take it home.” He just handed it to me and put a new one up there. I’ve still got it to this day. I thought it would be nice to have it.

This bomb was so new and different to us, we didn’t understand it, and didn’t know the consequences. We never heard a thing about radiation and all of that, and it took a little while for that to sink in, but it didn’t make an impact about whether we felt it was a moral thing to do or not. We didn’t examine any of that. We decided that the war was over and that’s good enough for us, no matter what.

We waited around there a couple of more weeks for some kind of an assignment, and they said everybody’s going home. Then we took the whole squadron, and the last thing they did, and I don’t know why they did it, but we were all loaded up, we had all the base force people on the boat, and a lot of material, luggage, and all that stuff. Then the squadron commander sent a crew in there to douse all those tents and buildings and everything with gasoline and set them afire. That’s what he did. All the natives were waiting; they knew the war was over too. They were waiting to occupy those tents and everything. I thought it was a very senseless thing to do, to burn all that. Those natives were shaking their fists at us and everything. I thought it was terrible, but anyhow, that’s the way we left that base: in flames. Then we went up to Samar, and as soon as we got there—the engines still hot—we had orders to pull the engines out of the boat. I remember opening up our CO2, a big tank, you know, that they put out the fires and stuff with? I sprayed it on the engines, just to cool them off, and it cooled them off quite a bit!

Then we went down and started dismantling the engines. The next day they came and pulled the engines out and dropped them in a dump truck and took them along the shore of the island and just dumped them—all the engines out of all those boats—they dumped them in a big pile on the beach just a little ways in the jungle. Then the hulls, they put them another place, set gasoline afire to them and burned them. There again, I don’t know why they just didn’t give them away to those Filipinos. They could have used the boat hulls for housing if nothing else. There was nothing sentimental about the boats from a practical point of view, but we thought that it was a lot of foolishness to just destroy them. They should have just gone ahead and given them to somebody who could use them. As far as I know, those engines are still there.

I got on an LST, and it took us thirty-three days to cross the Pacific. That’s when we stopped at Pearl Harbor. They wanted to pick up some supplies. They wanted a volunteer. I said, I’m gonna go ashore here, and I jumped on this truck, drove into this base, threw on a few packages, jumped in the truck, and was back on the ship. I suppose I had my feet planted on Hawaiian soil about ten minutes. To this day that’s all the time I’ve ever spent in Hawaii.

When the war was over I was ready to go home. I just figured, you know, I didn’t join the Navy for a career. I was more interested in helping win the war and doing my part.

But my hearing was damaged being down there with those engines. I didn’t even notice it at the time, but one of the other crew members brought it to our attention. He said, “Why do the motor macs talk so loud?” He was talking to guys from another crew, and they said, “Well, our motor macs, they’re the same way; they talk loud.” They passed it around and they found out that all these guys that spent a lot of time in the engine room were loud talkers when they were playing poker. You know everybody talks kind of quiet, except these guys. They talked loud. Well, the motor macs didn’t realize they were talking loud because they could hear their own voice, and it didn’t sound very loud to them because their hearing was affected. Then we began to notice, to pay a little attention to our ears, and I noticed my left ear didn’t work very good. I was fully unaware of it, and my right ear seemed to be pretty good. Then when I got discharged, they wanted to know if I had any disabilities because of the war. I was so happy that I came back alive that I figured what the heck is a little hearing loss? That doesn’t amount to anything compared to your life, so I thought I got by pretty good. So I didn’t complain. I thought if I complained they’d keep me there for two or three more days. I said I have nothing to put down, but then after that I used to do almost all my hearing through my right ear.

I sometimes think about fear, and what was it like to face the enemy fire and all that, and how fearful did I get? But it appears it doesn’t work quite that way. When you become involved in combat, fear doesn’t even enter the picture. It’s excitement. And you get intensely excited, you know? It seems like it takes away the fear. You get so excited that you can’t calm down for a long time. It isn’t really fear; you’re just really cranked up like you had way too much caffeine.

You know, to tell you the truth, I think I’ve been that way ever since. After the war I always have had a sort of a difficult time relaxing. I don’t know what’s the cause of it, maybe it’s in my genes. I don’t know, but I get involved or excited pretty easily. If I have an exciting evening I can’t go to sleep. I think there’s a lot of people like that anyhow so maybe I’m not any different from anybody else, but excitement has been kind of my problem. I mean keyed up. It was after the war when I began to notice it. I don’t remember being that way when I was a kid before the war. In fact, when you’re riding PT boats, they kind of have a policy that if you ride a boat for six months and you’re in any action, they say that’s enough. You don’t need to ride any longer. You’ve taken your chances and you came through it, and they’ll find somebody else to take your place.

I had this opportunity to get off the boat when I was in the Mediterranean. I got to thinking, you know, you get on the base force and it’s just like a civilian job, from 8 to 5, and I thought, oh, that isn’t any fun at all. It just seemed so drab and so monotonous. I decided I didn’t want that. I’d rather ride the boats because it’s kind of like riding a motorcycle; it’s more exciting, more fun. They’d go more places. I kind of think I became addicted to the darn boats. I just kind of loved it. I can’t explain it, but it was hard to leave the boats behind.