OPPOSITE: John Beddall front row center) poses with members of his B-25 crew, back row from left, Lt. Bryant, Capt. Bus Knight, Joe Csizmadia; front row from left, Pete Downs, Beddall, and a pilot from another plane. Photo was taken on Makin Atoll in front of the B-25 “Broad Minded.”

I enlisted in April 1941, from Idaho. I had some friends who thought it would be a great idea if we all joined the Army Air Corps together. I wasn’t quite eighteen so my parents had to sign for me. I went home, and when I told them my mother started crying, but my dad said, “It’ll probably do you some good.” So he agreed to sign for me. Well, it turned out that none of my friends enlisted, for one reason or another, so I went in alone.

During training I got the request I wanted, to be a radio operator on a bomber, and the location I wanted, which was Tucson, Arizona. So I ended up being a radio operator/gunner on B-25s. I shipped out first to Honolulu where we did training. We were doing fully loaded short takeoffs and we thought they were going to put us on a carrier.

Then I was based for ten months out in the Pacific, and I was based on Makin Atoll. We were flying bombing missions to targets in the Gilberts and Marshalls. I flew a total of fifty missions. On my fifth mission we were sent over to bomb the Japanese-held atoll of Maloelap where they’d built an airstrip on one of the islets called Taroa. We’d come in real low on these missions to bomb and strafe, so we were right at coconut height. I was shooting things up on the ground with the right waist gun as we zoomed over the airstrip, and all the other guns on the plane were firing. Suddenly, I heard something hit the plane and turned to look out the left waist gun window, and there was thick black smoke trailing out of the left engine. It turned out that ground fire had hit the prop governor and part of the engine had been shot away. First the propeller started windmilling faster and faster until the engine seized up, and then the propeller just stopped turning. Since the prop blades were flat to the wind, they created a lot of wind resistance. It’s amazing that my pilot was able to keep control of the airplane with one engine shot out so close to the ground.

So there we were, a long way from home, out over the ocean with only one engine. My pilot, and he was a great one, was Bus Knight. He was a University of Nebraska football star, and he played in the 1941 Rose Bowl game. So, he was nursing our B-25 along on one engine running wide open, barely above the surface of the ocean. Over the intercom he told me to throw anything heavy overboard to see if we could gain some altitude. Taking the waist guns out of their mounts was normally a two-man operation, but since the engineer was still in the tail gun position, I did it by myself. I put my foot up on the frame of the open waist gun window to brace myself, reached out with one hand and grabbed the barrel of the machine gun as far out as I could reach, and with the other hand yanked mightily on the butt end of the gun. It pulled right out of its mount, and I pitched it into the water. The adrenaline was really flowing! We were so close to the surface that the spray was flying up from the ocean, and my foot got wet when I put it up on the frame of the open waist window. I did the same with the other waist gun, and then started to pull up the two steel armor plates in the floor. Each was about three feet long, one foot wide, three-quarters of an inch thick, and about 200 pounds in weight. But the adrenaline was pumping and I yanked the first plate up from the floor, got it up on the waist window frame, slid it out of the plane, and into the ocean it went. I was just starting to get the second one when Pete suddenly came up behind me from out of the tail gun position, grabbed me, and yelled that if I threw out that plate it would cut off the tail! Of course it wouldn’t since the tail of a B-25 was above the level of the waist gun windows and I had just thrown one big plate out with no problem. So I just grabbed him, bodily threw him back toward the rear of the plane, and finished throwing out the other armor plate. I never talked to him after that, and he never flew another mission.

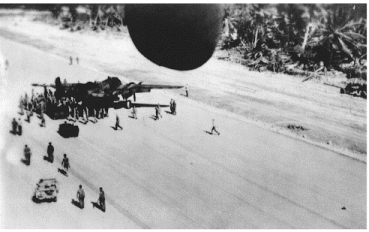

John Beddall’s B-25, with one engine shot out, has just braked to a stop on the nearly completed coral runway on Majuro Atoll. The plane, piloted by Bus Knight with Col. Solomon Willis flying as co-pilot, was the first American aircraft in WWII to land on a Japanese mandated Pacific island taken back from the Japanese. This was an honor being prepared for Admiral Nimitz and the Navy, but fate intervened on behalf of the Army Air Corps. Seabees and other naval personnel crowd around the plane.

On our maps the closest atoll with an airstrip we could land on was Majuro. Well, the Marines had just taken that atoll from the Japs, and the Seabees were sprucing up the Jap runway to get it ready for a Navy plane to be the first to land on an atoll that had been forcibly taken from the Japanese. But we had an emergency and we had to come in and land. Another of our B-25s, named “Luscious Lucy,” had been flying beside us to make sure we made it. The pilot buzzed the runway to get the Seabees out of the way, and then we came straight in and landed okay.

But there was a complication. Admiral Nimitz was commander of the Navy fleet, and when the runway was finished he was going to take off from a carrier, circle the atoll, and land on Majuro as the newsreel cameras rolled. That would make him the first American to land on a prewar airstrip that had been owned by the Japanese. So here we come, an Army Air Force B-25, and landed on the runway before Nimitz could have a chance. So that ended the celebration they intended to stage for Nimitz landing on Majuro, and the Navy wasn’t real happy about this! They sent four Navy captains over right after we landed to inspect our plane. They figured four captains would outrank any officers that could have been on our B-25, and normally that would have been the case. But on that mission, our colonel, Solomon Willis, was flying in the right seat with my pilot, his good friend Bus Knight. So it was a stand-off, with Col. Willis being of equal rank with the Navy captains. We lined up in front of our B-25, and the Navy captains lined up in front of us. They could see right away that we had a legitimate reason for the emergency landing, and they didn’t really know what to say. They felt they needed to say something, so one of the captains sees me, an enlisted man, lined up next to Col. Willis. We were right under the machine guns in the nose of the plane. So this captain comes up to me and says, “Aren’t you going to clean those guns?!” I just moved a little closer to Col. Willis and said, “No, sir!” Col. Willis stood his ground and defended me from the Navy. We had to abandon our plane right there at Majuro since they didn’t have any repair facilities.

So until they could fly us back to Makin, the enlisted men, me included, were put up in a tent on Majuro, while the officers on our crew were taken out to a ship. But to eat dinner, they came and got us and took us out to that ship, and I’ll never forget that meal. Here I had been eating powdered eggs and minimal food like that for weeks, and in front of us in the chow line was what seemed like a feast, and there was two of every category: for potatoes they had baked and mashed, for meat they had pork chops and beef, and so on. I couldn’t believe how good the Navy ate!

After that our crew was sent to Honolulu for R and R. We were catching rides on planes headed that direction, and on one leg we were in a B-24 that was being ferried back. We were taking off from Kwajalein, and on our take-off run I noticed that we had gone past the last runway marker and were still on the ground. I started to get worried that this pilot was going to run us right into the ocean off the end of the runway. Well, we got to the end of the runway and the pilot just raised the landing gear, but the plane stayed at the same altitude. This didn’t seem like a good situation! The left wing dipped a little bit as I was looking out at the palm trees whizzing past, and then we were over the ocean, still right on the deck. But that pilot got the plane straightened out, and we started climbing real slow and made it to Honolulu.

When we got there, I headed out to a recreation center that had been set up next to the Royal Hawaiian Hotel. It was a low building with card tables, pool tables, and—this was the best part—fridges with bottles of cold milk. We all wanted to drink milk—it had been so long since we had tasted it. I would just pull a bottle out of the fridge and drink that ice cold milk, and it tasted so good!

Back at our base Col. Willis had this little dog named “Pistol Head.” He used to whistle to it, and the little dog would come running. Pistol Head was kind of the squadron mascot, a great little dog. Well, one day Col. Willis was driving a Jeep back from the officers club. It flipped over and he was killed. This came as a blow to the squadron, a real tragedy. After that the dog just kind of moped around. He kept thinking Col. Willis was going to come back. Well, one day one of the guys was joking around and saw the dog hanging around. So this guy imitated Col. Willis’s whistle. The dog perked right up, thought his master was back, and came running, but couldn’t find Col. Willis. That was about the crudest thing I ever saw—that dog was so disappointed—you could just see it searching around for its master because he thought he heard the whistle. That still chokes me up to think about it.

Our missions were usually around four hours round trip. We bombed Jap bases on a lot of little atolls in the Gilberts and Marshalls, and also Ponape. We were told to never be taken alive. If we were over a Jap island and were hit and couldn’t make it, just push the controls over and nose it in. We heard the Japs killed enlisted men outright and tortured and then executed the officers. We think this is what happened to Capt. Colley and his crew. His plane crashed near the shore of an island, and we saw four of the five crew make it out onto their raft. APBY went out to pick them up, but the Japs beat them to it. We never saw or heard from those guys again. Ten years after the war they were officially pronounced dead.

I think my experiences in the Pacific affected me, and of course I’ll never forget what happened. In 2002 my wife, Hazy, and I did a cruise around the Pacific islands with a lot of other veterans. We stopped at a couple of the atolls I was on during the war. As we went along I learned all about what the others did, and it was interesting to hear all the different types of experiences they had. I was only in one small bit, flying out over the atolls and islands, and some of those guys had a lot more dangerous jobs. But I did my part, I did what I was trained to do, and I survived. I volunteer at the Mesa wing of the Commemorative Air Force. I have a notebook with photos of B-25s and some of the islands we bombed, and we have a B-25 there in the hangar we are restoring. People look at the plane, and I show them the photos in my notebook and tell them about my experiences. I think it helps them to relate to the Pacific war if I’m there and they are looking at the B-25 and can hear a little bit about what we were doing out there.