OPPOSITE: Wartime photo of A.C. Kleypas.

I got drafted in a funny way. When I got out of high school I was eighteen years old, and that was in 1942. I had another brother who’s two-and-a-half years older than I am. I got a draft notice so my mama went with me to the Draft Board and I said, “Hey, what are you doing drafting me? I’ve got an older brother at home and he wasn’t drafted.” The guy there says, “Is that right? Well, what’s his name?” Sure enough they had lost my brother’s records, even though he had his draft card and everything. So anyway, they looked at me and mom and said, “Well, one of ya’ll’s gotta go right now. Either you or your brother can go, but one is going now.” I looked at my mama, and I didn’t want to say it, but I said, “I’ll go.” My brother stayed at home an extra year.

I wanted to get in the Air Corps, so I took a bunch of tests and got in. They sent me to radio school, basic training, in South Dakota, then all over, including Yuma, Arizona. I finally ended up in California, and they shipped us overseas out of San Francisco. I ended up being a radio operator on B-24s. And on a B-24 the radio operator was also a gunner.

So we flew a brand-new airplane across the Pacific, and made a lot of stops along the way. I remember one was at Christmas Island and another was Guadalcanal. They were still shooting there at nights. Then we flew out the next day, and we landed at Townsville, Australia. I forget how long we stayed there, probably two or three days. But it was there we had to give up our brand-new airplane. We were just flying it across the Pacific so somebody else could get it.

From Townsville we got on a ship, a little old stinkin’ boat, smelled like goats. Took us three days and we went to Port Moresby, New Guinea. There were about three or four airfields where they operated out of there. We used to go down and bomb the Celebes, some islands way off to the west. Anyway, we did a lot of missions out of New Guinea. Another place we flew out of was right across from Biak Island on the north coast. It was a little island by the name of Owi. This little island was just airstrip from water to water. It was nothing but just a coral island like all these islands were. And we used to take off there and fly long missions, most of them were ten or eleven hours over water all the time, and we bombed a lot of different islands. We even went over to Balikpapan on the island of Borneo. That was a long mission for us, and let me tell you something about our two missions over there. You know, you heard about the Japanese and the kamikazes, and how they’d fly their planes into our ships? Well, on that Balikpapan mission, that’s the first time they kamikazed an airplane in the air that I knew of. They took fighter planes and tried to fly them into ours, and if one rammed a B-24 with a crew of ten, then it took ten American lives for one Japanese. That’s not bad, is it? That happened over Balikpapan, and that was where all the Japanese oil fields were.

Their planes would come at you, and you couldn’t really shoot them. The chance you’d shoot one of those planes down was one in 50 or 75 or 100. It’s not as easy as they make it look in the movies. It’s the real thing and it’s a lot harder. A lot of times they’d just come up from the bottom of the formation and try to ram us.

We were making the first bombing mission from Angaur to bomb some town in Formosa. We were taking off the first day, and our lead man, the big boss himself, got a little bit off on the side of the strip and hit a plane over there and cut the end of the wing off, and they crashed. We were the next to take off and we got about half way down the runway, and we had to stop. We were carrying 1,000-pound bombs, and the bombs from that lead plane that just crashed started going off, so we had to cancel the whole mission. It was raining, it was raining real hard. One of the guys on that crew, the radio operator, was a real good friend of mine. In fact, part of the crew I usually flew with was on that plane including my copilot. See every now and then they would split us up. So those guys died and I didn’t. I still have trouble with that.

But our planes were close to crashing all the time. We took off at Owi one time and were so loaded down we couldn’t get off the runway. And the copilot was screaming at the pilot, “Pull it up!” I was standing right behind him. We cleared the end of the runway and we were over the ocean right away, but we hadn’t gained any altitude. We just put the landing gear up, and we were about six feet off the water, loaded with all those bombs, and we couldn’t gain any altitude. If there would have been a six-foot wave, we would have hit it and crashed!

So when I had flown probably twenty missions, we went over to Palau because we couldn’t land at Leyte. They had the invasion of the Philippines up there in Leyte, and they also had a strip up in Palau. We were supposed to go up there and land on that strip and operate out of that strip. When we’d move, all the base moved. They would put them on the LSTS, you know, our tents and our cookstoves and the people that were on the ground that maintained the planes, they would all get on the LSTS and go up there. Well, they landed up there, but we took off with the planes and couldn’t land there. So they diverted us, and we went over and landed at Angaur, which is in the Palau islands. We had no food or anything, and we had to bum our food. We lived on K rations there for a long time. We had to dig our own well for water. We had it rough there for a while.

After we finally got away from there, we went over to Samar in the Philippines. We used to fly from there, and once they captured Manila they moved us to Clark Field, and we flew out of there. That’s when we did a lot of bombing up at Taiwan, and they really had the antiaircraft guns up there.

When we went over there to Palau the Seventh Air Force was based there. They had all new airplanes, had everything so fine, and here we were a bunch of crumbs. We didn’t have anything. Some of our planes had 100 missions on them. We had come up from the lowest place you can get, down in New Guinea. You never see our planes on film or anywhere because there was never a report. Nobody ever took pictures or anything, because no press would ever go there. We never had anything filmed, no war correspondents. None of them wanted to go there it was so bad, so we got no coverage and no one knew where we were, and people still don’t know anything about what we did. Who knows that American planes bombed the Celebes? No one’s even heard of the Celebes, and that was true during the war and right up to now!

I had several close calls. We had a lot of times when we’d come back with three engines. I’d have to put out a Mayday alert call on the radio in that case. They would give us a direct shot and locate us and track us all the way in case we lost another one, because we couldn’t go on two engines. We were coming in on three engines one time and fixing to land, and we didn’t have much of a control tower to keep track of the landing pattern. We were just about on the ground, and all of a sudden there was another plane that pulled out right under us. We almost had some kind of major crash because we didn’t have any power to maneuver with only three engines. We had a lot of close calls like that. We’d get a lot of holes in the airplane, engines shot out, but no major crashes. I never parachuted out or anything like that. But I would have jumped out several times if we would have been up higher. I told a guy once, “I’m getting out of here,” and looked down and we were about 100 feet off the ground. Ain’t no way that’s gonna work!

On my missions I made sure I took my parachute and my flight jacket, my survival kit and my escape kit. But really, if you got shot down, you didn’t have a chance. They’d kill you. We bombed Formosa up there one time. They call it Taiwan now. We had some planes shot down. I know we killed thousands of people. We dropped magnesium fire bombs. They’d come in big clusters. When you dropped them they just looked like confetti falling. When they hit the ground they’d go off, and you can’t put them out unless you put them in a bucket of sand or something. That place was one massive ball of fire when we left.

We lived in tents on dehydrated food, powdered milk, and powdered eggs. We used to have a good breakfast. We could get hotcakes out of that mixture, along with gallon cans of strawberry preserves. We ate good food, but fresh meat or anything like that? We never had any. We had what we called bully beef, which came from Australia. It was corned beef. I thought it was fun. I was nineteen, twenty years old. I didn’t know any better!

If you flew a ten-hour mission it took you about fifteen hours all told. We’d get up at 3:00 in the morning and go to briefing. We’d get something to eat, get this, get that, get in the plane. When you got back you’d do it all again, but in reverse. You’d have to go to debriefing if there was anything important. If there wasn’t anything important happened, a lot of times they’d let us enlisted men go, and they’d just talk to the pilot and copilot.

I was out at our swimming pool one day a couple years ago and my wife Shirley hollered at me. She said, “Hey, somebody’s on the phone.” And it was Memorial Day, so I picked up the phone and this guy says, “Hey, have you ever flown on a B-24?” And I said, “I know who you are.” I said, “You were my engineer, weren’t you?” I hadn’t seen him since 1945. He found me over the internet, and so we’ve been corresponding ever since. He lives in North Carolina. He’s my age. He stood up there and he’d tell the pilot when the gear was down. We took off one time, and it wasn’t a bombing mission. We had to fly a lot of times when we didn’t get credit for flying, see. A lot of times we went on missions just to test airplanes, test the engines. When they’d change engines we had to go do a little reconnaissance run, take up new people, and so forth. Anyway one time they sent us somewhere on New Guinea to pick up a load of black powder. Now what we were doing with black powder I don’t know. They don’t tell us, they just say go get it. So we landed on another one of those metal strips down there, and loaded the cases of black powder. When we started taking off we lost an engine, No. 4 engine, and here we had this load of black powder. We barely got airborne and we came around to do an emergency landing, trying to get back down on that air strip. Well, that old copilot—he’s dead, he got killed later on—he feathered that prop. Well, to feather the prop you pushed a button in and then turned it loose. Well he pushed it in but then held it down. That old engineer knocked him off of that thing because it goes through the props and it goes right back in. Well, if you don’t feather the prop at such a resistance, the thing turns and it just shakes your plane up. Then as we were coming down, the landing gear wouldn’t come down. The engine that had quit also had the hydraulic pump on it that lowered the landing gear, and the hydraulic pump was out because the engine was out. So somebody looked out and said, “Hey, we ain’t got the landing gear down!” Well, here we go up and around again, wide open and trying to get enough altitude to make another turn and come around again to make a landing. We had to crank the wheels down by hand, and finally came in and landed. That was a close call.

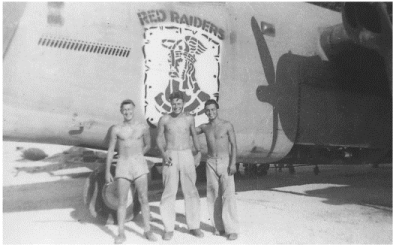

A.C. Kleypas (center) and two buddies pose in front of one of his squadron’s B-24s on Owi Island, near Biak on the north coast of Papua New Guinea

When we bombed Corregidor the Navy had shelled it already, and there was nothing there but just bare rock. It was just so bombed it was just a wasteland. When we moved from New Guinea and went up to the Philippines, it was like we were going to the Waldorf Astoria! We got those natives over there to build us a frame out of bamboo. Then we would put our tents on top of it, and we had us a nice place. Things were looking up, really uptown. And they would wash our clothes for us. They started out at about fifty cents and ended up about five dollars. You know how those things go, don’t you? One of them comes and says, “Me wash your clothes, fifty peso.” And the next one comes, “Well, I’ll give you a dollar, here take that.” Then somebody else would give him two, and it’d keep going up in price.

I was living in tents the whole time I was in the Pacific. I never spent a day anywhere except in Army tents, and usually we took our raincoat and put it across the bar that held our mosquito nets. Of course the tents always leaked and it rained all the time, so the raincoat would keep the water off. It was like camping out for over a year. We flew during the day all the time. I never flew a night mission.

The way we knew we were flying a mission was that there was this bulletin board, I guess you’d call it, and if you were on a mission they’d have your name on there and what time you were leaving. We didn’t know where we were going or anything. We’d get up the next morning and we’d go to the briefing and they’d tell us where we were going. We’d go by the lunch place and pick up a box of cold, beat-up sandwiches, and they’d always give us some kind of an artificial drink made out of grapefruit juice. We had canned grapefruit juice and stuff. Everything we had was canned. So we took lunch with us since we’d be gone ten, twelve hours. We would leave when the sun was barely coming up or earlier. We’d get back before the sun went down most of the time. I had a seat because I sat next to this radio. The waist gunners didn’t have seats. They’d just sit in the back, sleep, whatever. I was up with the pilot and copilot. We were just this far apart anyway; there was just a little partition between us. We’d test our engines every time before we’d take off. We had to get twenty-nine inches of mercury and 2,700 RPM. If we couldn’t turn that on four engines we couldn’t go.

On takeoff I was supposed to get my back up against something to brace in case we crashed, but I would watch. I’d look over the shoulders of the pilots. If we didn’t have 100 miles an hour when we passed the control tower, which was usually located in the center of the strip, then we were in trouble and we would never make it. So I was looking to see if we had 100 miles an hour halfway down the strip. I wanted to see if we were gonna make it. Me and the engineer would always stand there right behind them on the takeoff. A lot of times we’d just have to turn around and go back because we just couldn’t take off, couldn’t make that. The biggest danger was failing on takeoff.

I could never do it now. You were just scared to death all the time. Then you gotta worry about getting to the target because we always flew over the water, and there was no rescue for us. If you had to go in, a B-24 doesn’t ditch very well. They didn’t hold together very good because the bottom, the bomb bay, was made out of like a roll-up garage door. And you had a big catwalk going down the middle of the bomb bay. You had to take your parachute off to walk down through there. That’s how tight it was. Well, that usually just caved in, and if you hit very hard it would break that plane in half. Everybody used to call the B-24s “flying cremators.”

One of the worst flights I ever had was when we went through a hurricane and we didn’t know it. See, we didn’t get good weather forecasts. Supposedly we got them from the Navy, but half the time the Navy wasn’t there either. That storm we flew into was the most horrible thing. I guarantee you, we’d hit downdrafts and would lose 500 feet just like that. The pilot and copilot would put their feet against the dashboard and pull back on that yoke with all they had to try to pull it out of a dive. It was raining so hard the water was coming in every crack in that airplane. It was coming in there like you were pouring it with a sprinkler. That was the worst weather I’ve ever seen. I guess it was a typhoon. We were in it about thirty minutes, and we had no radar.

When we were flying in tight formation and we’d hit bad weather, how do you know where everyone else is? You can’t see a thing, so what you’d try to do, you’d try to spread out. We would fly out to these places on all these long missions, and we would never fly totally all the way in formation because you’d burn up all your gasoline. So we’d kind of all fly on our own out to a rendezvous point, and then we’d start circling out there at a given time, and try and get into formation. Every now and then someone wouldn’t make it. They just wouldn’t show up, and sometimes that was it, we’d never see or hear from them again—just vanished over the ocean somewhere.

When I came home I was full of scabies. Do you know what scabies are? It’s like mildew got to you. It’d just eat you up, being in that constant heat and humidity down in those islands. Right after I got back I was a little nervous there for a while. I wouldn’t talk about it. I never talked about it. And after I got out of the Air Corps, I didn’t ever want to fly again. The last time I got out of that B-24 at the end of the war, I said that was it—no more flying. For thirty years I would not fly. We finally took a trip to Las Vegas on an airplane, and this was thirty years after the war, and I was scared to death. But during that first flight I asked the stewardess if I could go up and talk to the pilot. She told me no. They won’t let you in that cockpit, but he came back there and talked to me. He said, “When we land I’ll let you come up front and I’ll tell you about everything.” Well, I was wanting to get off then! It was mostly just, I guess, tension, and I didn’t want to get back in an aircraft. So many times I’d get up in a B-24 out over the Pacific during the war and I’d look down, and it’s so far to fall, you know, I just felt very uncomfortable. I could tell, flying on those B-24s, by listening to every sound if something was wrong. Every sound, every little thing, if something didn’t sound right you’d know it. You’d fly up there, you’d hear those engines, you’d know if they were running smooth. There were so many times that planes didn’t come back, just disappeared over the ocean, and I knew how easy it was for that to happen, so I always was listening for trouble. After the tension on all those flights, worrying about the plane and whether we’d come back, that’s why I didn’t want to ever fly again. But once I got over that, and it took thirty years, now we fly all the time.