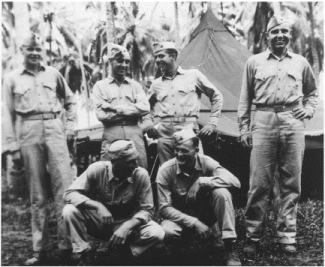

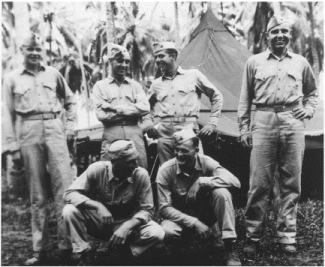

OPPOSITE: Jim Milliff (standing at far right) and fellow Marines on Guadalcanal shortly after surviving their combat experience on Bougainville and prior to the invasion of Guam. Standing from left: Chester Lawson, Frank Brandemhil, George Walters and Milliff; kneeling from left, Edward Spielbush and Elbert Ross Underwood.

I went down to enlist on December 8, 1941. One of those “Pearl Harbor Avengers,” I was going to join the Navy, but a friend of mine talked me into the Marines. He had been turned down by the Marines in the morning on account of his teeth, so he went and got his teeth fixed. He said, “Let’s just see if we can pass the exam.” And, boom, we were in! But they didn’t take us until December 19, because they were signing guys up at the rate of a thousand a day, and the Marines were only used to handling 200 per day.

Before I went overseas, the captain said nobody goes to officer’s school. But they’d give us tests, and every time we’d take a test I’d come in first. I guess that shows you how dumb the rest of them were. And so he kept saying that nobody goes to a military school, but with my test scores I thought I would have a chance. I was a private first class, and we had a brand-new NCO from the reserves. I used to box a little, so I said to him, “This is your chance to show how tough the Marine Corps is.” And then this corporal referred to my ancestry in an inferior light, so I hit him. Actually I just shoved him. And for that I went to the brig for twenty days on bread and water. That also ended any chance I had of being an officer. But then, I’m here, and a lot of those guys that were good officers aren’t here!

The two biggest ocean liners in the U.S. at that time were the America and the Washington, and I went across the Pacific on the America. We didn’t go in convoy because that thing could go twenty or thirty knots. It could run away from the Japs, and it had a 5-inch gun on board. The skipper on that thing had been the skipper on one of the ships at Pearl Harbor, and every time there’d be reports of Japanese in the area, we had to sit out on deck with this 5-inch gun. I was in the ballroom up on the promenade deck. There were about six berths in a stack, and the stacks of bunks were so crammed in there you could barely move. But since I was a sergeant, I took the top bunk so nobody could climb down on top of me. But when we got out in the Pacific we just stayed out on the deck.

We went to New Zealand, to a little town just north of Auckland. We trained there for a while, and then we shipped out for Bougainville, and we landed at Empress Augusta Bay. You know, we’d pulled up offshore of this island, and you’re sitting there out on the ocean, and it’s a beautiful, sunny day, eight o’clock in the morning. And you’re standing there, looking around to see what you can see. And these little plops are hitting the water, you know? All of a sudden, it dawns on you, “Hey! They’re shooting at us!” There’s nothing you can do.

It was really rough, you know. We went in on landing crafts at Bougainville, and we lost a lot of them. The Coast Guard was bringing us in. So we did the run in to the beach, and then you hop out of the amtracs. That’s a scary thing, too, because you’re about a good seven feet in the air, and you have to jump out onto the beach with the Japs shooting at you. And you’re thinking that every one of the enemy is aiming right at you.

But when we did go inland on Bougainville, it was like one big swamp. So, there we were in a swamp, and all we had ever learned to do in training was dig in, but in that swamp you had to do the reverse and build up little islands out of the muck. We were in this swamp for a while, but they kept moving us up. Finally, there’s a hill in front of us. We were on the front lines, and all of a sudden here come the Seabees to bulldoze that hill down out there in front of us. And we said, “Hey! Do you guys realize that this is the front lines?” “Oops!” So then they went back, and they said, “You’d better move those Marines forward.” So they moved us forward, and we were there for sixty days on the front lines in the jungle and didn’t come back that whole time. What they finally did was build a perimeter to keep the Japs away from the airstrip they had built there, and then they brought the Army in to relieve us, the Americal Division, I think it was. They held that perimeter for the rest of the war. They never took them off Bougainville. So then they brought us back to Guadalcanal, and we get down there and there’s a whole big military city, a great big city with a beautiful, massive airport and the whole business.

The next operation we were in on was the invasion of Guam in 1944. We landed at Asan Point, Third Marine Division, Ninth Regiment. We came in on “Blue Beach.” We went up across the beach and dug in. There were high cliffs ahead of us beyond the beach to the right and left. So, I told the guy ahead of me, “When you’re gonna move, let me know.” They were shooting at us, and we were laying low in holes we made for ourselves in the field behind the beach at the foot of these cliffs. And so when he decided he was going to move, he started throwing rocks at me to get my attention. Well, I dug deeper—I thought I was receiving fire! Pretty soon the word comes back from our colonel. He wants a machine gun up there. Well, I’m a machine gunner, so I go up there with another machine gunner, and we get fire and my gunner gets killed. And another bullet goes right by me and hits the colonel. So we didn’t have to see any more of that colonel. And we had our ammunition dump along there, too. The Japs blew it up, and we lost about 120 men that day.

Then a guy said to me, “There’s a Jap in there,” and he pointed to a cave in the cliff. So, there’s a Marine I knew coming by with a flamethrower, and I said, “Hey there’s a Jap in there.” And so he turned the flamethrower in there. Seven Japs ran out, and we shot them. Then the next day, they brought the Seabees in, and they just mined that whole cliff and all their caves and blew it up. They brought a war dog with them. And the war dog and his leader, they went around the bottom of the cliff and checked the caves. And if the dog goes “GRRRRR,” then the Marines start scrambling. A war dog is a messenger and he smells out the enemy. He does all kinds of work. We used them first on Bougainville. And they’re really like humans. They crack up if they get too much work.

They got a rank, too. I said to the guy, “What rank’s your dog?” He says, “Sergeant.” And I said, “What’re you?” He says, “I’m a corporal.” His dog outranked him.

So, we got past that first set of Jap positions, and there was a hill up behind them farther up from the beach. We came up there and the Japs had this hill, but it looked real familiar. It was just like this place where we had trained on maneuvers in California called Murphy Canyon. So we all looked at one another and said, “Murphy Canyon.” The captain says, “Murphy Canyon. First Platoon on the right, Second Platoon on the left, and the Third Platoon in the middle.” And when the machine guns started firing, everybody charged just like in training. We took that hill and only lost one man. And you could see it from the harbor. One of the chief surgeons was out on the ship—he was from my hometown. And somehow he found out from guys coming back that I was in there in that deal, and so he wrote a big, glowing letter back home about what a wonderful outfit we were.

And then we turned and took a pass to the right. And then they took us farther down to the right to take a little island just off the coast, Cabras Island, I think it was, and we rode over on amtracs and jumped out. We went in there and I thought, well, we’re going to lose the whole company here. And we jump out of the amtracs and there’s a great big pillbox staring at us, a big, black hole, you know? So, bam, bam, bam, bam, and we are all shooting at it. And I yell, “Down men, let’s sneak around.” We sneak up to it, and of course, it’s empty.

Sure the Japs were terrible and did a lot of bad stuff, but sometimes we were just as bad as they were. I had a guy in the outfit that would knock the teeth out of dead Japs, and he had this whole jar full of gold teeth. But the only thing that most of us took were the flags, mainly, and some valuables. We discouraged that gold teeth business because it was just, you know—things can get worse and worse.

We finally got inland a ways and we had dug in on the slope of one of the hills. Capt. Dave Lewis put the Company on a Third Watch, which meant that every third foxhole had a Marine on watch. No matter what the watch, you only slept off and on during the dark hours in combat. I was in a foxhole with two other Marines, Alcorn and Hobson, with our light machine gun. We always found a two-forked stick and put it in front of the foxhole, so when we awakened at night, we knew which direction was front. It had been the kind of day where it rained and then the sun would come out, you know, off and on. And that night the moon was out, and we could look down this hill in front of our foxhole and there was a little road down there a ways.

And I looked and I saw about ten or twelve Japs coming up that road in the moonlight. Well, I reached back to get my weapon to kill them, but the Marine who had stood the last watch in the hole had wrapped all our weapons in a poncho to keep them dry from these passing showers, so I couldn’t get a weapon out real easily. So, I thought, well, I’ll lay quiet, because I knew if I turned around and rummaged around trying to get out a weapon, they would see me and might shoot me.

Well, one of them was coming up pretty close, so I figured I’d lay quiet, and after he goes by I’ll unwrap my rifle and shoot him. Well, he didn’t go by. He saw me and he came at me with this big Samurai sword, and he was going to behead me with that thing. I had seen those sabers, and in training we’d been taught that even though you didn’t have your weapon, you still weren’t unarmed, you had your hands. I planned that when he swung the saber down, I would deflect the blade with my left hand. I am right handed, and if I lost the left hand it wouldn’t be so bad for me. So it worked out just like I planned. I deflected the blade with my left hand, caught the back of the blade with my right hand, yanked him off balance, kicked him with my right foot, stuck my left foot in his belly, rolled onto my back in the foxhole and lifted him up in the air on my foot so the Marines in another foxhole could shoot him.

And I’m doing all this thinking, and I could hear somebody yelling. A Marine in the far foxhole started shooting with his .45 and hit the Jap. One of the bullets, evidently, ricocheted off the parapet and went into my right hip. But I didn’t know it at the time. I had this tight feeling in my hip, but I thought I’d got kicked in the fight. And then, I hollered “Cease fire!” And I kicked the Jap off my foot. Well, he goes up in the air, and the guy starts shooting all over again. So, I yell again to cease fire, and he stopped firing. I looked at this Jap and he was kind of breathing, so I let him have one out of my .45, and that was that. But all during this, I could hear some guy yelling. At the end I realized my mouth was open, so when I shut my mouth the yelling stopped. It was me—I was the one who had been yelling! It was like I was two people, the trained me who is fighting off this Japanese guy like I’d been taught, and the real me who is scared to death!

When daylight came we called for a corpsman, and we discovered that I couldn’t walk. The corpsman, Hills was his name, cut the right pant leg off. I told him to stop, that I needed those pants. He said, “You’re through with this war, Marine, you don’t need them, because there’s a bullet lodged in your right hip.”

They took me back there to the field hospital, and they had some antiquated X-ray machine. I didn’t know how bad I was hit, you know. I knew that my hands were cut pretty bad, because that was where I’d grabbed the saber.

They noticed I had an entrance wound in my hip, but they couldn’t find the bullet. They said they could see where it had gone in, but it didn’t come out. Well, if it didn’t come out, it must be in there somewhere. So, while I was in the hospital the Japs had broken through, and in the hospital they gave all of us weapons. We had to stay there in the hospital but be ready to defend ourselves. Luckily the Japs didn’t get to our hospital and the breakthrough was turned back.

I was in the hospital just for a short time, and the hole where the bullet went in healed over, so they sent me back to my company. And I said, “What about the bullet?” And they said, “Well, we can’t find it.” And that’s when I said, “Well, it didn’t come out.” They didn’t know what to do, so I went back to my outfit.

I got back, and next thing we were marching down the road when the lieutenant halts us and says, “Left face.” And we left face and he says, “This is our campsite.” And it was a jungle. We said, “How are we gonna put tents in here?” He said, “Clear it.” We said, “How’re we gonna do it?” And he says, “You got bayonets!” So, pretty soon, you heard, “Fire in the hole!” Guys are getting down and BOOM! They were blowing up trees. They were blowing up everything. I looked out as we got things cleared off and there was a beautiful beach. So, we built the camp there.

After a while I went over to the hospital to see them again, and I said, “Now, look. There’s a bullet in here somewhere, because I can’t walk right, and the thing must be right up against the joint.” And so they took another X-ray and said, “Oh, yeah, there it is.” They still had that piece of antiquated equipment, but this time they aimed it right. So I said, “What’re we going to do about it?” And the doctor said, “Oh, that’s inoperable. They may take that out when you get back to the States, sometime. But for now go back to your outfit.”

So back I went. They were making sweeps of the island, and I was assigned duty as a police sergeant. I stayed back and kept the camp clean with a detail. And that was my job. So, pretty soon they brought in guys who had been over any length of time, and they were going to be sent home. The captain said, “Okay now, I’ve put down the names of the men that have been good performers out here. And we’re gonna send them home first in the order they’re drawn.” They just drew the names. So the first guy drawn was a guy named Quick, whose brother had been killed. The next was me. My mother had just died and I had a bullet in my hip. And so I got sent home on that.

So when I got home I found out that after I was wounded, for some reason, they had sent a letter to my folks that I’d been killed. But I was already home when the letter got there—I beat it back. And the notice was in the Oakland Post Inquirer, and it’s gone and I’m still here. But when I came home I was probably never in better shape in my whole life, 190 pounds and no fat. My dad took a look at me, because I was yellow from taking Atabrine for malaria, and he starts shoving the food down. I went back to the base, and people that I’d served with didn’t even recognize me. My dad had said, “You get that bullet out of there, and you do it right now. Don’t wait.”

So in late 1944 when I headed back I was assigned to duty up on Bainbridge Island, Washington. And that was interesting, too, because that’s where they were breaking the Japanese codes, only I didn’t know it. There were 100 sailors, 78 Marines, and 500 WAVES—and that means 500 women—on this base. And, you know, you get to think you’re a lady’s man with those kinds of odds. They always told us it was a high-frequency radio school, and all we were there for was in case there was sabotage, but we were really there to guard the code breakers. It was a beautiful duty because if you wanted to go into Seattle, that was fun, but why go to Seattle—you had everything at the base there. Bowling alleys and WAVES and everything.

While I was there I went to the hospital over at Bremerton. They brought in this commander of the hospital, who was a captain. And he sat down and said, “Well, okay, sergeant. Now, how’d the bullet get in there?” So I told him. Pretty soon they go out and they bring in somebody and it was Gregory Peck. He was visiting the hospital, and he wanted to hear about it so I was telling him, and he shook my hand. He was a big, tall guy and visiting with the USO or something.

So the doctors all got together and they said, “Well, we’ll call you.” I went back to my base, and after a while I got a call. I went back over there and there was this Dr. Kowalski. He looked like Groucho Marx. He looks at me and says, “Oh, yeah, sergeant, I remember your bullet in the right hip.” So I says, “Think you can get it out?” “Yeah, I can get it out.” And I said, “They told me that it was inoperable.” Well, he got in there and it was rough. He had to take the whole hip apart to get it out, because the bullet was rammed in there. And he told me later, “You know when you were overseas and that first guy told you that stuff about it being inoperable? He was right!” But Dr. Kowalski got it out and he gave the bullet to me. I have it at home. It’s an American .45, so all of my hospital reports had to say, “Not self-inflicted,” because it was an American bullet.

I got the Purple Heart, and they also gave me the Silver Star there in Bremerton for that little incident with the Jap officer and his sword. I didn’t know anything about getting it, but it had been written up by my lieutenant. The commanding officer they had in the Marine barracks was a minister in civilian life. He had been a Marine in World War I. So he gets us all lined up there and he calls, “Sergeant Millgriff.” He was mispronouncing my name so bad I didn’t even know that he was talking about me. Pretty soon, the old Marine gunny says, “He needs you! GET OUT THERE! March out there!” So, I marched out there, and the first I knew I was going to get the Silver Star was when they presented it to me.

So I got the Jap’s sword and his pistol. I still have the sword. I gave the pistol to my brother Bill to hold for me because I was moving around. And Bill walked in his sleep, and he lost the pistol. He thinks he may have done something to it when he was sleepwalking. But he never found the pistol. It was a beautiful pistol. He felt bad about it, but he doesn’t know what happened to it. And, of course, I still have the scars on my hands. They’ve faded now, and you can barely see them. Over the years I must have told that story of the Jap that charged me with his sword a hundred times, but people keep wanting to hear it.

I’m still in touch with a lot of the guys I served with. I’m active in the Yolo County Marine League, and the Golden Gate Chapter of the USMC 3rd Division Association. I try and go to the reunions, and I even edited our newsletter for a while. Just about all of us who are still around got wounded at one time or another, either on Bougainville or Guam or Iwo. Getting wounded on Guam may have saved my life, since a lot of my friends in my unit got killed on Iwo.