To get a satisfactory print, one that contains all you intended, is very often more difficult and dangerous than the sitting itself.

—Richard Avedon, Observations, 1959

In the mid-twentieth century, a “good” photographic print was often defined by photographers, photography editors, curators, collectors, and dealers by comparing it to the work of Ansel Adams, Minor White, and Edward Weston. Adams’ style of photography, often known as “straight photography,” has inspired untold numbers of photographers. This style intends to maximize the technical possibilities of photographic materials, so that the blacks are true blacks, the whites are true whites, and there is a great range of gray tones in between. This approach to photography lends itself well to landscapes and other images in which there’s a sense of capturing “reality.”

Avedon’s photographs indicate that he has no need of or desire for straight photography’s heightened reference to real-world actualities. In 1997, he told a New York Times reporter, “There is no such thing as photographic reality.” He was interested in making photographs that were psychologically stirring. To do that, he manipulated his negatives and prints. Adams once described negatives as scores of music that could be interpreted and reinterpreted. Avedon’s negatives, however, become the basis for photographs that were treated more like canvases wet with oil paint.

Richard Avedon’s Observations, published in 1959 with text by Truman Capote, provides insight to his working methods. That book shares more than a title with the series of photographic essays in Harper’s Bazaar. Stylistically similar, the full-bleed photographs are accompanied by minimal text and significant white space. In the book, Capote quotes Avedon: “When I’m photographing, I immediately know when I’ve got the image I really want. But to get the image out of the camera and into the open is another matter. I make as many as sixty prints of a picture, would make a hundred if it would mean a fraction’s improvement, help show the invisible, the inside out.” The negatives and prints on these pages are an opportunity to explore what Avedon meant.

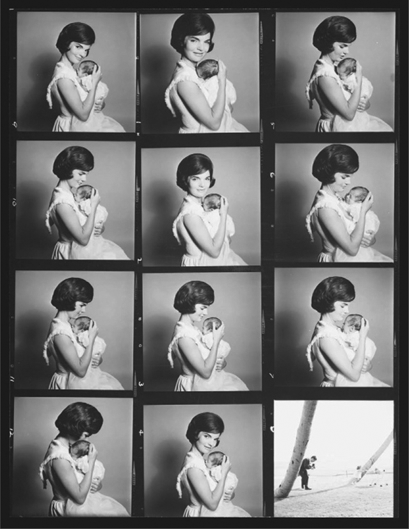

Examining Avedon’s contact sheets and comparing the many images there to the ultimate image Avedon selects offers some insight to his intentions. This contact sheet in which Jackie is holding John Jr. is a good example. Following conventional rules about portraiture, the center photograph in the bottom row showing Jackie slightly smiling and looking at the camera would be a natural choice because she appears happy and is directly engaging the viewer.

The image at left in the bottom row shows Jackie holding John Jr. about as tightly as a mother can; his nose is even a little smashed to her chest. She’s cradling him in a way to protect him and to hold him close. Although Avedon is looking to “show the invisible,” in this case a mother’s love, the baby’s head hides too much of Jackie’s face. The emotions have gone too far, overwhelming the photograph and leaving no psychological or physical tension. Avedon takes a step back from this intimate moment and avoids sentimentality by selecting the second image in the first column for the Harper’s Bazaar spread.

The chosen photograph shows Jackie looking slightly beyond John Jr. while still holding him close. Her chin and his head are just touching. His face is barely above the surface of her dress. She cradles his head, but grips his body. The result is a more complex portrait of Jackie: a beautiful, intelligent woman and a loving, protective mother. This image was the third picture in the series of photographs selected for Harper’s Bazaar.

Avedon’s ability to move a portrait beyond a mere physical resemblance of the sitter has as much to do with the original exposure of the negative and image selection as it does with his printing choices. Not only does he capture the moment and select his image, but he also prints the photograph in a way that emphasizes or underscores his intent. On page 36, the photograph of Jackie and John F. Kennedy seated on a bench where Jackie’s ring finger is bent illustrates this point.

Compare the digital scan from the original 2¼-inch negative to the final print. Looking at the scan, it is easy to see that the negative started out evenly exposed. To achieve a gray background with the existing white paper background in this photograph, Avedon turns down his lights while taking the picture. The result creates a more sculptural image of the sitters.

When the film was processed, it was rolled onto a metal reel. A darkroom assistant accidentally bent the film, which caused the half-moon on John F. Kennedy’s sleeve. The halo around Jackie’s hair is bromide drag, which occurs when the negative and the developing chemicals are not kept in enough motion. If this happens, there is an excess of bromide created along an edge where darks and lights meet and overexposes the light side. These are both fairly common darkroom mishaps.

The top image is a digital scan from Avedon’s original 2¼-inch negative. Below it is Avedon’s final version of the photograph.

Most photographers utilize dodging and burning techniques to modifying the negative’s exposure to the photographic paper. Generally, this is done to even out the tonal qualities or bring out details in a negative. Under the enlarger, Avedon’s photographs experienced quite a bit of controlled dodging and burning to move the print towards his vision of the final image. Avedon guided the printing of his photographs by giving instructions to his printers to shape the specific details and nuances in his photographs.

In this photograph, he uses dodging and burning for two purposes—first for practical reasons, second for aesthetic ones. In the original negative, the light is cast evenly across the couple. By darkening the area on Kennedy’s sleeve, the bright half-moon is dimmed. However, the print becomes so dark that the pattern in Kennedy’s suit and the texture of Jackie’s dress are obliterated. This darkening encourages the viewer to focus on something other than the superficial details of the fabric.

Through dodging and burning, Avedon lightens Jackie’s skin so that she almost looks like a porcelain sculpture. The overall lighting in the photograph is also redirected so that it highlights Jackie’s neck and both of the couple’s hands.

Retouching is another technique that shapes the photograph for practical and aesthetic purposes. Here, Kennedy’s wrinkles are softened. Jackie’s neckline is sculpted by removing the dress along her back towards her shoulders. The left side of her face and hairline are softened. The overall effect of dodging, burning, and retouching removes details to focus on the sitters themselves, emphasizing Jackie’s fragility and Kennedy’s sturdiness. Although this image was considered for the Harper’s Bazaar photography essay, it was ultimately omitted.

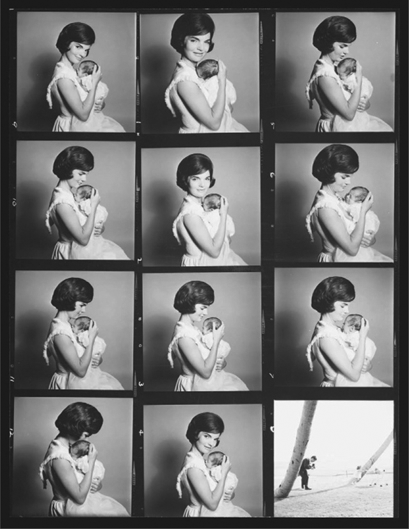

The third set of images (at right) demonstrates the more practical aspect of retouching. The final image appeared in Harper’s Bazaar as the fifth photograph in the series. During the sitting of Jackie in her pre-inaugural gown, the heels of her shoes punctured the backdrop paper. Simply applying a matching gray tone to the negative removed the holes. In this case, a photographic print was made in which the holes appeared. An 11 x 14-inch copy negative was made of that photograph, then retouched before being sent to the printer. As part of the process, the printer sent back proof prints to Avedon and Harper’s Bazaar for approval, then went on press. Proof prints for the Harper’s Bazaar spread are in the Richard Avedon Collection at the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona.

The following pages provide an opportunity to examine a selection of the Smithsonian collection of Richard Avedon’s Kennedy photographs. There are sometimes striking differences in the look of the photographs because Avedon made only nine final prints of the 219 photographs in the collection. The square images are digital scans from the negatives represented on the contact sheets. They were printed as conventional photographs because there was no reason to attempt to print them with Avedon’s aesthetic. The contact sheets and the rectangular images are printed as closely as possible to Avedon’s version of the photographs. Taken with the information provided here and the reader’s own perspective, the Smithsonian collection can be experienced in a unique, contextualized way.