Linda Raedisch

Witches call it Mabon. Christians called it Michaelmas in honor of the Archangel Michael, a spirit who had his own shadowy beginnings in the ancient Near East.2 Here in North America, few Christians have even heard of the Feast of St. Michael, though they might have heard of the Michaelmas daisy, a wild aster that dots the woodlands from late summer to early fall. Up until fairly recently, Michaelmas was an important spoke on the year’s wheel. In 1680, an English colonist writing home from the remote wilderness of the colony of New Jersey listed all the berries he had gathered “from the time called May until Michaelmas.”

If ever a season had a color, it’s the Michaelmas season, and the color is purple from the lavender petals of those asters to the brighter, more pinkish hues produced by the pokeberries that are ripening at this very minute. (If you make your own pokeberry ink, wash your hands very carefully afterward and keep both the berries and the ink away from children and cats: it’s highly poisonous to everyone but birds.) Blackberries leave a darker purple stain. At Michaelmas, they’re having their last hurrah. In fact, in England it was considered bad luck to eat blackberries on or after Michaelmas. However, if you really have to have a blackberry on Michaelmas Day, it might be worth the risk: some say the bad luck doesn’t kick in until Old Michaelmas which, since the switch from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar, now falls on October 10.

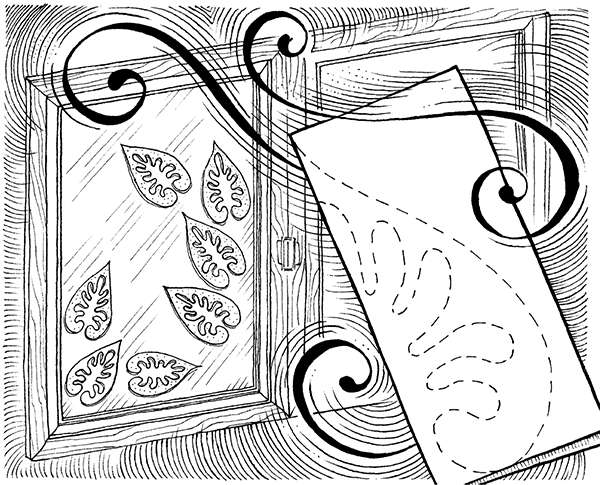

Medieval Window Leaves

Like my Candlemas snowflake, this design was pilfered from an inlaid medieval paving tile. In the original, the design would have been stamped into the leather hard clay tile. The veining in the leaves was then filled with a darker colored slip. Our process is more economical, for each leaf you cut out will yield not one but two leaf shapes.

If you’re going out to buy some watercolor paper anyway, why not invest in a decent set of watercolor tubes? They work so much better than the dry little ovals of paint you can buy in the school supplies aisle of the grocery store. And when you use tubes, you don’t have to worry about muddying the colors. Thin down some red to turn it pink, dab it on the wet paper, add orange and yellow, and let them bleed together. Yes, some leaves are still a little on the green side when they fall, but if you add green blotches to the mix, keep a buffer zone of yellow around them so they don’t blend with the red and make brown. Brown leaves are for November.

And then again, you might want to tint your leaves in shades of lavender and mauve.

Time frittered: Just minutes per leaf.

Cost: About $20.00, less if you’ve already got a decent set of watercolors.

Supplies

A sheet of not too thick watercolor paper or not too thin drawing paper: in other words, paper that can get a little bit wet but is also easy to fold and cut through.

Clean sponge or paper towel

Watercolor paints

Palette, either store bought or a piece of wax paper

Small paint brush

Clear tape*

Dab your paper with a clean sponge or paper towel until it is just a little more than damp. You don’t have to wet the whole paper at once; you can wet as you go.

Squeeze a little paint onto your palette and thin well with water. Dab onto wet paper with brush. If it neither spreads nor bleeds, you should either add more water to the paint or re-wet the paper.

Add more colors, but don’t go overboard: a limited palette is best.

When the paper is all colored, set it aside to dry and prepare your leaf template. This can be cut from printer or other ordinary paper. I suppose you could cut it straight out of this book, but I really don’t approve of cutting pages out of books.

The template represents half a leaf (or half of two leaves.) When your paper is dry, cut it into manageable, slightly larger than leaf-sized pieces that you can fold in half. Trace the template onto the colored paper, cut out, unfold, and there are your first two leaves. Make as many as your sheet of paper allows.

Now all that remains is to arrange the leaves artfully in the window, securing them with little rolls of tape. You might also consider gluing them to black or dark gray cardstock to make Michaelmas cards, an item that the stores these days just don’t seem to carry.

Book Broom

If that early New Jersey colonist had occasion to sweep his New Jersey doorstep, he probably would have reached for a birch broom or “Indian broom.” Birch brooms are not made like Witches’ besoms; in fact, they were not made in the Old World at all. The colonists learned from the Algonquian tribes of the eastern woodlands how to score, peel back and bind the layers of birch wood into an effective cleaning tool.

My Book Broom is modeled after the birch broom. Because it’s now September, and we’re all feeling a little bookish, it’s made from the page of a book, or, rather, a photocopy of a page from a book. (Because I don’t approve of cutting pages out of books.) In true back-to-school spirit, I took mine from “Chapter Eleven: Quidditch” in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.

In my younger daughter’s beloved Ever After High series of books, the students play “Bookball,” so when I’d finished the first prototype of my broom, I presented it to said daughter and announced, “It’s a Book Broom!”

“What for?”

“For playing Bookball, of course.”

She patiently explained to me that Bookball is not played with brooms; they just throw a book around like a football.

I’m sticking with Quidditch.

Time frittered: About 15 minutes

Cost: 15¢, assuming that you don’t have to pay any library fines before you’re allowed to use the photocopier.

Supplies

One 8½" × 11" sheet of paper on which you have photocopied a page from your favorite book

Ruler (optional)

White all-purpose glue*

Fold your sheet of paper in half like a book and cut along the fold. You only need one half to make one broom. (You will need one little strip from the extra half, so don’t recycle it yet.)

Fold this half page in half again, again like a book, but don’t cut.

Unfold and turn page print-side down.

Cut the left half of the page into vertical strips, but don’t cut all the way to the top edge; stop about 1¾" from the edge. The strips should be about ¼" wide. It’s up to you if you want to measure; I prefer to eyeball.

When you have cut your row of strips all the way to the center crease, stop and turn the paper print-side up. Starting at the uncut side of the page, roll the whole thing up. Rolling it around a pencil or drinking straw will help to make it nice and tight which is what you want since this is going to be your broom handle. When you’ve rolled the whole page, strips and all, glue the seam securely.

It doesn’t look much like a broom yet, does it? That’s because it’s not nearly finished. Pull the strips down one by one, revealing the text. Bind them with a narrow strip of that extra paper and secure with glue.

Speaking of books, as I was composing this year’s “Crafty Crafts,” books would regularly march themselves off their shelves in my living room and pile themselves on the kitchen table. They had come to help. And though our year-long paper trail of crafts ends here, if you suddenly find yourself wanting to know more about medieval tiles, Swedish manor houses, birch brooms, or even paper itself, the following books can be summoned to come and help you too.

Books

Bell, R. C. Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations. London: Oxford University Press, 1960.

Hughes, Sukey. Washi: The World of Japanese Paper. San Francisco: Kodansha International, 1978.

Jacobson, Dawn. Chinoiserie. New York: Phaidon Press, 2001.

Sjöberg, Lars and Ursula Sjöberg. The Swedish Room. New York: Pantheon Books, 1994.

Tolkien, J. R. R., and Baillie Tolkien, ed. Letters from Father Christmas. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1999.

Wilbur, C. Keith. Indian Handcrafts. Chester, Connecticut: Globe Pequot Press, 1990.

2. Michael’s deepest identity may be found in the asterism known as the Pleiades. The archangels Michael, Gabriel, Raphael, Raguel, Remiel, Sariel and Uriel from the Book of Enoch probably evolved from the Mesopotamian Sebittu, a tribe of axe-and-dagger-wielding gods who were often represented by two parallel rows of three dots each plus one dot at the end.