John’s little sister, Franny, had disappeared.

She and John were on their way to their schoolhouse. They were halfway through the three-mile walk from their farm. They were following an old wagon trail that cut through the tall, golden grass.

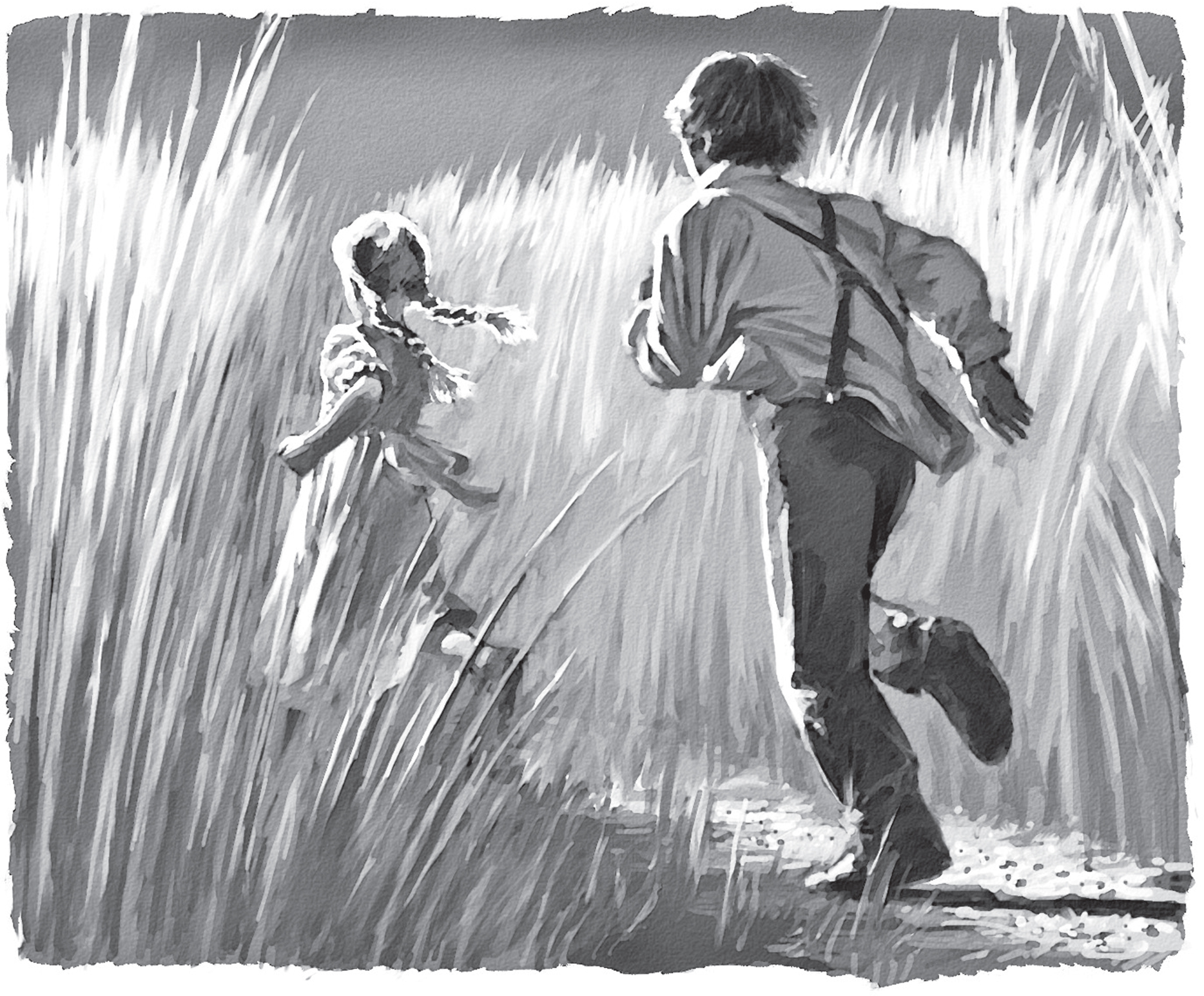

Franny, who was five, had been skipping up ahead. John had been watching her blond braids flap up and down, like the wings of a happy yellow bird. Somehow he’d lost sight of her.

John sped up, looking all around. It was hard to see through the grass, which rose up so high it tickled his neck. A unicorn could be prancing by, and John wouldn’t notice.

“Franny!” he shouted. “Where are you?”

Whoosh, said the wind. Swish, said the grass.

But no sign of Franny.

John sighed. She must be playing hide-and-seek, her favorite game. When Franny found a good spot, she’d sit there forever.

She was going to make them late. It was hard enough for John, going to a school where he had no friends. But his teacher, Miss Ruell, was mean.

He pictured her now, her hair stretched back in a bun, her eyes glaring through her little round glasses. She was young, and barely five feet tall. But she ruled over the schoolhouse like a Civil War general. John had never once seen her smile. When kids were late, Miss Ruell made them stay in for recess and memorize some boring poem.

Torture!

“Franny!” John shouted.

He stood on his tiptoes, peering into the distance. All he could see, in any direction, was wide-open prairie. It seemed to stretch out forever, an ocean made of grass.

He still couldn’t get used to it, all this empty land.

John and Franny and their parents had moved here to Dakota about a year ago, from Chicago. It wasn’t John’s idea; he’d been happy living in the city. But Ma and Pa were fed up with their dark little apartment, their cursing neighbors, and the noise and stink that rose up from the street.

For years Ma and Pa had been talking about moving out west and buying a farm. But John always figured that was just their crazy dream, like John wishing he could be a pitcher for the Chicago White Stockings, his favorite baseball team.

Pa didn’t make much money, working at a cabinet shop. How could they ever afford to buy land for a farm?

Then Ma and Pa heard they could get land in a place called Dakota. It was thousands of miles of open space, west of Minnesota. Dakota wasn’t a state, but it would be soon, folks said.

And the government wanted farmers to come. They were even giving away big plots of land — for free! All you had to do was build a farm and stay for five years. Then the land was yours forever.

For Ma and Pa, it was a dream come true.

“We’re heading west!” Pa boomed.

“We’ll be pioneers,” Ma said.

John hoped the West would be like the places in his favorite adventure stories, with rivers filled with gold nuggets and brave sheriffs chasing after famous bank robbers like Billy the Kid.

Ma and Pa sold practically everything they owned. They traveled west by train — it took seven days to reach the edge of Dakota Territory. Then they bought a rickety wagon and an ox to pull it. John named the ox Shadow, after his favorite White Stockings pitcher, Shadow Pyle.

It was a two-day ride to the little town of Prairie Creek. If you could call it a town. Only about twenty families lived there, on little farms scattered across the prairie. The main street was a dusty strip of dirt with a general store on one side and a hardware store and tiny hotel on the other. John’s family settled on a 160-acre piece of land about two miles outside of town.

There were no rivers of gold, no brave sheriffs. There wasn’t even a bank for a guy like Billy the Kid to rob. There was only empty space — and endless work.

John and Pa were sometimes out in the fields from dawn until dark. Ma hardly ever stopped scrubbing and cooking and sweeping. Franny’s scrawny little arms had sprouted muscles from hauling buckets of water from the well.

And the weather! The roasting summer sun. The thunderstorms that blackened the skies. Winter days so cold your spit froze before it hit the ground. Blizzards that came out of nowhere. Last winter the snow piled up almost to their rooftop. Pa had to dig a tunnel to get from the house to the barn.

But for John, the worst part was the emptiness. He got a lonely feeling when he looked out over the prairie, an ache inside him. It felt like a cold wind blowing right through his chest.

John didn’t belong here. He felt stranded in the middle of nowhere.

And now Miss Ruell was going to punish him for being late.

“Franny!”

But wait. What if Franny wasn’t playing a game? She could have wandered too far into the grass and gotten lost. Last year a little boy from town disappeared. One minute he’d been chasing jackrabbits behind his family’s house. The next minute he’d vanished.

John and Pa joined the big search, but the poor kid was never found. It was like the prairie had opened its grassy jaws and swallowed him whole.

John cupped his hands around his mouth and yelled at the top of his lungs.

“Franny!”

The grass swished. The wind moaned. A flock of geese honked across the bright blue sky.

But no sign of Franny.