9

Henry

As the drone of the departing bombers faded, on the ground around Bruneval a silence was restored that is almost incomprehensible, given the defenders’ awareness of the airborne intruders. Nearby Germans afterwards reported that their radar sites tracked the incoming British aircraft – W120 at Sainte-Adresse warned Luftwaffe Centre at Octeville, even as the Bruneval Freyas and W110 Würzburg did likewise. These alarms caused most of the local personnel not manning anti-aircraft weapons or equipment to take to their shelters, anticipating a rain of bombs, an apprehension that persisted as successive waves of British aircraft swooped low, and continued to do so at intervals through the ensuing twenty-five minutes. The lighthouse crew at Cap d’Antifer spotted overhead aircraft dropping paratroops – moonlight provided illumination to both sides, especially with the added glow from the snow carpet. A few minutes later, local army and air force personnel saw Frost’s men descending, and sounded the alarm. Just after 0015 senior Luftwaffe NCO Rudy Lang hurried into the radio room at the Gosset farm and phoned his local headquarters at Étretat. In a first call he said he thought the bombers might be dropping dummies. Then he telephoned again to announce that the new arrivals were, instead, indubitably live paratroopers.

As for the elements of the Wehrmacht roused from slumber in and around Bruneval, they had been deployed on the French coast to resist British incursions from the sea and, for that matter, to meet a full-scale invasion such as was unlikely to come for years. Nobody appears to have briefed the soldiers to regard protection of the Würzburg as a vital responsibility. Rather, they treated the radar installations as Luftwaffe technical stuff – no rightful business of the army. There was no senior officer within reach, to grip the defence in its wholly unexpected predicament in the first hours of 28 February. Major Hugo Paschke, the local battalion commander, was asleep at his spacious headquarters in the Manoir de Saint-Clair, a couple of miles east of Étretat. Meanwhile the commander of the Luftwaffe’s 23 Flugmelde, Prince Alexander-Ferdinand von Preussen, on the previous afternoon announced to his staff in Sainte-Adresse that he was off to ‘make a personal tour of inspection’: Mountbatten’s smart cousin then departed for a night in Paris, from which he returned only next morning.

Following news of the landings, confusion overtook the German staffs in and around Étretat. Those were days when many men could not drive, and even for Hitler’s legions vehicles were by no means universally accessible. The Luftwaffe’s Lt. Joachim Ruben shouted for his driver, to discover that the man could not be found. Precious time was then wasted, seeking out another vehicle and somebody to drive it. But at last, and before Frost’s men plunged into action, Ruben and two NCOs were guiding an Opel staff car up the steep, icy road that rose from Étretat to the plateau and thence to the Gosset farm, twenty minutes south of the town. According to the German after-action narrative, ‘all Army and Luftwaffe posts in the area were at once alerted … Scouts sent from the Freya position and the Luftwaffe Communications Station [at the Gosset farm] returned with information that the enemy was on the move south of the farm, in the direction of the Château [Lone House]. The parachutist commandos had split into several groups and were converging on the Würzburg position and on the Château.’

Yet despite all this, the Germans left it to the British to fire the first shots of the night, almost forty-five minutes after Frost and his men dropped from the Whitleys. The major knew that time was vital; also that he had only one choice – to attack with the men to hand. John Timothy and the available twenty-five of his forty Rodneys deployed in an arc between the dropping zone and the château, to block the landward side of Henry against German reinforcements. Their firing positions commanded the approaches from the Gosset farm and La Poterie, with Corporal Ralph Johnston watching their rear.

Lt. Naoumoff’s last-come Drakes hastened some six hundred yards from their landing to the point directly north of the château and radar site, where they lay down in the snow with their weapons and waited for the Germans in the Rectangle – the Gosset farm – to react to the imminent assault on Henry. It then became their role to ensure that the enemy was unable to do so effectively, or at least to give warning of threats to Frost and his parties.

John Ross reported to Frost that Charteris and two sections of Nelsons were missing. The major responded: wait for them a few minutes, then go ahead with the plan anyway – head first for the pillboxes atop the cliff, between the Würzburg and the defile. He promised to reinforce the diminished Nelsons as soon as possible – Ross’s role was critical: no access to the beach meant no escape from France. The young captain, facing the daunting challenge of suppressing German defensive positions with only half the force mandated for the task, waited in vain for ten minutes, then set off with two sections, weapons cocked, up the slope towards the clifftop bunkers and, beyond and below them, the defile.

Sgt. Dave Tasker and a half-stick of this force warily approached the pillboxes on the north shoulder – Redoubt on the British model. To their relief they found them untenanted, and took possession. But they could see the heavy wire entanglements beyond and below, laid out as obstacles to amphibious invaders, but also blocking the way to the beach. They knew there were Germans on the Bruneval side of the valley. In accordance with orders, Tasker and his men remained at the emplacements. This was prudent, because if Germans reoccupied them, they could sweep C Company’s exit route with fire. Sgt. Jimmy Sharp and the others moved down the open hillside towards the defile, following Ross and his heavy section, which included two engineers equipped with a mine-detector to check and if necessary clear the beach, and two Bren gun pairs.

Meanwhile Frost’s and Young’s men trotted fast across the four hundred yards of rising ground between the assembly point and Lone House and beyond it the objective of Biting, Reg Jones’s holy grail, the Würzburg radar. They were momentarily checked by farm fences before approaching the château and Henry from the south side, at every step expecting to receive a burst of fire. They spent several minutes making a cautious tactical advance, then Gerry Strachan led men scaling the wall onto the château’s terrace, to ensure that this was undefended. When the others ran around the big building to its north entrance, far from needing to ring the bell they found the front door yawning open. A young Luftwaffe man posted there as a sentry, Willy Ermoneit, a farmer’s son from East Prussia with two brothers on the Eastern Front, after hearing shots a few moments earlier had dashed off towards the radar site, leaving just one German occupant of the big house, though of course the British, keyed to the highest pitch of anticipation, did not know this.

Lance-Corporal Georg Schmidt, a Wehrmacht communications orderly posted in a room of the rambling first floor of Stella Maris – Beach Fort on the British photos and fancifully named by its builders eighty years earlier ‘the castle of Kroumin’, half a mile below Bruneval hamlet and on the cusp of its beach – was wakened by his NCO, Sgt. Treinies. Around 0025 he was ordered, no doubt roughly, to answer the insistent buzzing of the field telephone. Schmidt lifted the receiver to hear the voice of Lt. Huhne, their acting company commander, calling from the local army command post in the little mairie of La Poterie, two miles distant. Huhne had just come in from a night exercise with the platoon billeted in that village, now in their welcome beds. He announced that from his own window he had seen British paratroopers descending: the Stella Maris group must mobilize immediately! Schmidt, oldest man of his section, who would not see thirty-five again, held his officer in low esteem – ‘in Russia he would not have lasted twenty-four hours in a command’ – but for now, Huhne was the Wehrmacht officer responsible for the local defence of Bruneval.

Within minutes of the passing of the overhead Whitleys, and well before Frost’s paratroopers fired their first shots, the men in Stella Maris were dragging on boots and gathering equipment, hectored by Treinies, who rebuked their sloth. Grenades were issued. A Châtellerault 7.5mm light machine-gun, once property of the French Army, was hastily carried to a firing position in the camouflage-netted trenches further uphill, from which it could cover the face opposite, open ground nearest to the drop zone where the enemy had been seen landing. A twenty-five-round magazine was slapped onto the weapon; the gunner took his place behind it. Just eight minutes after the alarm was given, according to L/Cpl. Schmidt, the Germans in the beach positions were ready to fire on the paratroopers, for whom they then faced a considerable wait.

These trenches, sited behind wire entanglements and running up the southern side of the deep defile around Beach Fort, had only recently been dug, and were unmentioned in the pre-Biting intelligence brief. They would become the pivotal obstacles to C Company’s escape; the Châtellerault would cause them more grief than any other enemy weapon that night. The problem for Treinies was that he commanded just nine men, including Schmidt the telephonist, to man positions between a knife-rest gate linking the dense wire entanglements where these crossed the road higher up the defile, and Stella Maris with its sandbagged emplacements, covering the beach. He immediately decided against dividing his tiny force, by sending men clambering up the steep face to occupy the pillboxes atop the northern side, which they could almost certainly have reached before Sgt. Tasker. They would all fire from the south side of the track, from the trenches above and behind Stella Maris.

Meanwhile in La Poterie, Lt. Huhne was struggling to assemble his own platoon, summoned from their billets; then to exchange live bullets for the blank ammunition issued for their night exercise, only just concluded; to prime grenades and prepare to fight, a contingency which at the previous dusk had seemed impossibly remote from these soldiers’ lives. Only after a protracted delay did the lieutenant muster fifteen armed men. Leaving behind cooks and suchlike, with these followers Huhne set off to cover the mile to the Gosset farm, advancing with extreme caution for fear of being ambushed by the British invaders.

Close at hand, what were almost certainly the first shots of the night, save for anti-aircraft fire, were unleashed by John Judge, one of Timothy’s Bren-gunners, when Sgt. Muir his section leader ordered him to shoot at the lights of a vehicle headed along the open track towards the Gosset farm. This was the Opel carrying Lt. Ruben and his two Luftwaffe NCOs, approaching from Étretat. Several bursts from a range of two hundred yards did no damage to the Germans but caused them rapidly to back up and seek a safer approach to the farm, from the north.

John Frost, poised outside Lone House, heard the firing and recollected that this was the appointed moment for his whistle. He gave four long blasts, clearly heard by both paratroopers and Germans, which signalled closure, or rather an explosive breach, of the night’s weirdly protracted silence. He and his men burst simultaneously through the château’s front door and terrace entrance, even as Young’s party started shooting around Henry. Seconds later, more gunfire was heard from the direction of the Bruneval beach defile – Ross’s sections in action.

The château proved bereft of furniture, filthy dirty. Floor by floor the paratroopers ran through each room of the big house, until they reached the attic to behold a solitary German, nineteen-year-old Luftwaffe man Paul Kaffurbitz, firing out of the window towards Young’s section. Though he sought refuge behind a chest of drawers, a burst of Sten fire killed the young German. Then the paratroopers clattered noisily back downstairs. Leaving just two men in the château, they followed their leader towards Henry, fifty yards westwards, from which they could hear firing and the detonation of British grenades.

John Ross and the Nelsons approached the beach defile only moments before firing erupted at Henry, around 0100, and at least thirty minutes after the nearby Germans had been alerted. The paratroopers were spotted straight away by the defenders already at readiness in the trenches above Stella Maris, where in January Pol and Charlemagne had trafficked with the rashly amiable sentry. According to the German account the strongpoints, now manned by Sgt. Treinies and his section, were so built that they were effective only against attacks through the ravine from seaward. It was true that the pillboxes high on the northern shoulder were seized by the Nelsons before defenders could be found to man them. Moreover, the house higher up the defile, dubbed Guardroom by the planners, proved to be undefended. The trenches above Stella Maris, however, enjoyed a good field of fire uphill, commanding both sides of the defile, and every movement on the opposite hillside was visible in the moonlight.

Treinies started his battle confused about whether the shadowy figures whom he glimpsed appearing from the opposite side of the valley, highlighted against the snow, might be Germans. He discharged a recognition signal, a red Very cartridge, to which he received no response. He fired a burst in the air from his MP34 machine-pistol, again to test for a reaction. When none came, he was sure the approaching figures must be enemies. He then released a white flare which hung over the hillside opposite, brilliantly illuminating Ross and his men. The Germans opened fire.

The Nelsons responded with their two Brens, eight rifles and three Stens, but to little effect. Ross yearned for a mortar, and indeed for more firepower of any kind. His heavy section had been tasked and briefed to deploy on the northern shoulder of the defile, providing fire support with the Bren guns for a direct assault to be executed by Charteris with three sections. In their absence, the Nelsons were ill-prepared and understrength to assume responsibility for the different role of clearing the defile and capturing Beach Fort themselves. For some time they exchanged fire with the enemy, while making little progress. In their immediate path lay a dense wire entanglement, forming an arc around the beach perhaps half a mile from end to end. Sgt. Bill Sunley began to address this with heavy cutters at the nearest point, striving to avoid drawing German attention and fire.

This was a moment when the white snow smocks left behind at Tilshead would have been a godsend: as it was, the dark figures stood out mortally clearly in the Germans’ sights, as did the muzzle flashes of their weapons. Treinies’ Châtellerault wounded Bren-gunner Les Shaw who fell hit in the knee, with a shattered tibia. His mate Jim Calderwood dragged him out of German view, then Sunley scrambled up and stabbed him with a morphia syrette. Sgt. Jim Sharp told Piper Ewing to drop his rifle and take over the Bren. Shaw eventually persuaded the others to leave him and get back to the fight, but here was an issue which dogged C Company that night: with no medics among the paratroopers, men who needed to concentrate single-mindedly on engaging the enemy instead tended mates whom they were unwilling even temporarily to abandon.

Neither side’s shooting did much damage to the other, except when men moved. German fire was insistently high, and British not much better aimed. Paratroopers tossed grenades, which fell well short of the German trenches. Frost spared a moment during the night to reflect ruefully that during training, ‘unfortunately we failed to spend quite as much time on the ranges as we should have done … There is no shortcut or substitute for skill at arms and, without this, fitness, discipline, enthusiasm and all the rest counted for little when there was a real enemy to contend with.’ An immense amount of ammunition was expended by both sides around Bruneval – next day the Germans would collect seventy empty Bren magazines – for an astonishingly small proportion of hits. Moreover while Sten guns were impressively noisy, which counted for a lot against hesitant enemies such as were the Germans whom C Company encountered that night, their 9mm pistol rounds lacked killing power beyond the shortest ranges.

The momentum of the Nelsons’ advance was lost. They would probably have fared better had they been dropped much closer to the defile at the outset, before the Germans were awakened, but nobody had thought of that. Now, instead, Ross’s one and a half sections were attempting to grapple and overwhelm the occupants of the trenches, with a third of the force which had been intended to perform this dangerous and difficult fire-and-movement. Bren-gunner Bill Grant was hit in the stomach just fifty yards from the German positions on the opposite face. Bill Sunley reached him, administered another morphia syrette, then with Grant’s mate Andrew Young dragged the stricken man out of German sight. Sharp took over the Bren, and when he glimpsed flame from the barrel of the German gun opposite, delivered fire so heavy that for a while the Châtellerault fell silent.

Yet they could keep shooting all night at the defenders in their trench on the opposite side of the wire and the track, with scant chance of damaging them. The Germans above Stella Maris, like those at the Gosset farm, hugged their positions and made no attempt to reach the Würzburg and thus to impede Frost and the engineers. But as long as Treinies and his handful of men continued to cover the beach approach, C Company seemed stuck. A protracted respite ensued, during which the rival combatants, facing each other across the defile, fired only intermittently.

Frost’s first impression on seeing the Würzburg, in those days when radar dishes were novelties, was that it resembled ‘an old-fashioned gramophone loudspeaker’. Young and his Hardys had taken possession moments earlier, almost unopposed. Only a tenuous network of crisscrossed, knee-high barbed wire encircled the radar installation, where a dense entanglement must have checked the attackers. The paratroopers picked their way through this slight obstacle without attracting notice. ‘Then we were seen,’ said Young, who had already eased the pin out of a grenade held in one hand. ‘Groups of Germans wearing overcoats over pyjamas climbed slowly up from dugouts and stood, hands in pockets against the cold night air, just watching us. None carried arms and we discovered later they thought we were German soldiers on manoeuvres.’

It was certainly true that the Luftwaffe men had known about the noisy little night exercise Lt. Huhne and his Wehrmacht platoon completed less than an hour earlier. But Young’s version, like all personal accounts of battles, is far from entirely accurate, not least because he went on to claim that he and his men ‘killed a lot of Germans’, which they did not. The Würzburg crew were indeed bewildered – some of them had been in France for only two days. But their NCO, Sgt. Gerhard Wenzel, was alerted many minutes before, and had since been struggling to rouse his men and chivvy them to take up their rifles. Wenzel was a jolly little figure, popular with the radar-operators who mocked him as ‘the old man’ – a twenty-five-year-old. His first revelation of the night had been to glimpse a big inanimate shape drifting down, which caused him to duck with his hands over his ears, because he supposed it to be a bomb, and expected an explosion. Then he saw a running man in the field eastward, and knew enemies were at hand. Meanwhile the set operator twenty-one-year-old Hans Senge – according to the German after-action report – was attempting to assemble an explosive charge to destroy the radar when Young interrupted his efforts with Sten-gun fire which killed him. Wenzel, likewise shot down, staggered or crawled away; was later found dead by the south wall of the villa, thirty yards distant. These, together with Kaffurbitz dead in the château, became the only three Luftwaffe fatalities of the night.

Young Willy Ermoneit, who had abandoned his appointed post in the château a few minutes earlier to explore outside, reached the radar site just as the British stormed it. He emptied the magazine of his Steyr sub-machine-gun towards them, without effect, before prudently taking to his heels. For this deed, in the Germans’ subsequent quest for heroes, he was awarded the Iron Cross, second class. His comrades on the site fled towards the Gosset farm.

One technician was so desperate to escape he plunged over the cliff, discarding his rifle and pursued by paratroopers. Peter Walker, the interpreter, joined Sgt. Greg ‘Mack the Knife’ McKenzie peering down at the apparently paralysed, certainly terrified, Luftwaffe man clinging on a few feet below, who was attempting the difficult feat of retaining his position on the cliff face while also sustaining a posture of surrender. Within a few seconds, in his own language Walker cajoled the man back up – they wanted him as a prisoner, not a corpse. Young erupted into a laughter which he had not expected to experience in the midst of a battle: ‘I thought I had seen nothing funnier than a German trying to scramble up the lip of a cliff with his hands up.’

Walker’s first act upon literally collaring the prisoner was to tear the Luftwaffe badge from his tunic. A bemused comrade asked: ‘Why have you done that?’ This German Jew answered: ‘For my personal satisfaction!’ The captive hastily proffered his wristwatch as earnest of eagerness to placate his captors, and this was pocketed by McKenzie – it is curious that, in every twentieth-century war, soldiers of all nationalities in peril of their lives have often snatched their enemies’ watches, portable trophies. Somebody urged killing the twenty-year-old, who was now sobbing and shaking in his shock and terror, but they knew they needed him in one piece. Peter Young and his men, in their enthusiasm for the assault, had been over-keen to kill Germans – his own sergeant certainly thought so – and forgetful of the priority of securing live prisoners to meet Reg Jones. Four of the latter had been able to bolt across the open ground northwards to the Gosset farm, leaving just the one radar-operator in British hands.

Silence was briefly restored around Henry, and the prisoner was hustled forward to be presented to Frost. Through Walker, the major quizzed the man, a technician named Heller who pronounced himself stunned; at this soft billet in Upper Normandy, he had not the least expectation of finding himself in the midst of a battlefield. The British officer demanded: did the men at the Gosset farm have mortars? If the enemy, who soon began shooting briskly from three directions, mortared the radar site, C Company would be in deep trouble. During the planned evacuation, they might inflict even graver carnage on the beach. Yes, answered Heller, they had access to the weapons; but had never done much with them. This was not true – the nearest mortars were at Étretat and Saint-Jouin – but the Luftwaffe man seems confusedly to have told the British whatever came into his head.

The Germans at the Gosset farm had already telephoned Étretat to demand an 81mm mortar, but this failed to arrive in time to be used that night. The British profited mightily from being pioneers, first significant raiders to assault Hitler’s French coastline. Later in the war, indeed later in 1942, Churchill’s armed forces would experience at bloody cost the speed and effectiveness with which German troops could respond, when confronted by intruders from the sea. That February night, however, the soldiers and Luftwaffe men who met C Company seemed capable only of firing on the British wherever they chanced to have men deployed.

A prime cause of German sluggishness in massing force remained uncertainty about the raiders’ objectives. The Luftwaffe men around the two Freyas, on the cliff beyond and west of the Gosset farm, held their positions to defend the big scanners, which they expected to be attacked at any moment. Questions were asked afterwards by their superiors, about why they had not hastened to join the battle around the Würzburg. Yet they were exonerated when it was found that, amid expectations of further British landings, they received insistent orders from Étretat to ensure at all costs that a radar watch continued to be maintained, and that the Freyas were protected from assault. Meanwhile south of Bruneval, in the sector occupied by the 336th Division’s 687th Regiment, its pickets who witnessed the descent of the misdropped paratroopers caused its headquarters to fear an attack in their own direction.

After Lt. Ruben and his NCOs came under Bren fire, they abandoned their vehicle and hurried on foot by a more circuitous route to the Gosset farm, where they found confusion among the Luftwaffe men. The three made a brief attempt to go further – to get to the Würzburg – but had advanced only a few yards when they bumped into Lt. Naoumoff’s Drakes. Surprised German and British voices first demanded each other’s surrender, then there was an exchange of fire in which neither side hit anything, before the Luftwaffe trio swiftly retreated into the night.

Back at the Gosset farm, the lieutenant sought to muster a fighting force, and found that the radar personnel had only a few rounds apiece for their rifles. Sgt. Karl Deckert volunteered to take their Opel by the north road to La Poterie and beg a machine-gun from the army. Arrived at the mairie, he was obliged to conduct a farcical negotiation with the NCO in charge, who declared defiantly that, airborne attack or no airborne attack, he would not surrender a single weapon to a Luftwaffe man without his company commander’s order. After much pleading, the soldier gave way and Deckert returned to the Gosset farm with a machine-gun and its two-man crew. This was set up even as Frost and his men milled around the Würzburg and the château.

As soon as the shooting had temporarily stopped in the immediate vicinity of Henry, Dennis Vernon ran forward, confirmed that the site was secure, then waved and shouted, ‘Come on, the RE’s!’ Around 0100, Cox and two engineers joined him, having cursed considerably about the difficulty of dragging their three trolleys through the snow, then heaving them over the Germans’ barbed-wire trellis, only two feet high but ten feet wide. Two of the awkward load-carriers were quickly abandoned as redundant. The raiders conferred momentarily: Young reported to Vernon that he had searched the château and dugouts without finding any documents such as Reg Jones wanted. Then Cox and the others, after donning rubber gloves to avoid shocks from high-tension cables, set to work with insulated tools on the big metal radar cabinet.

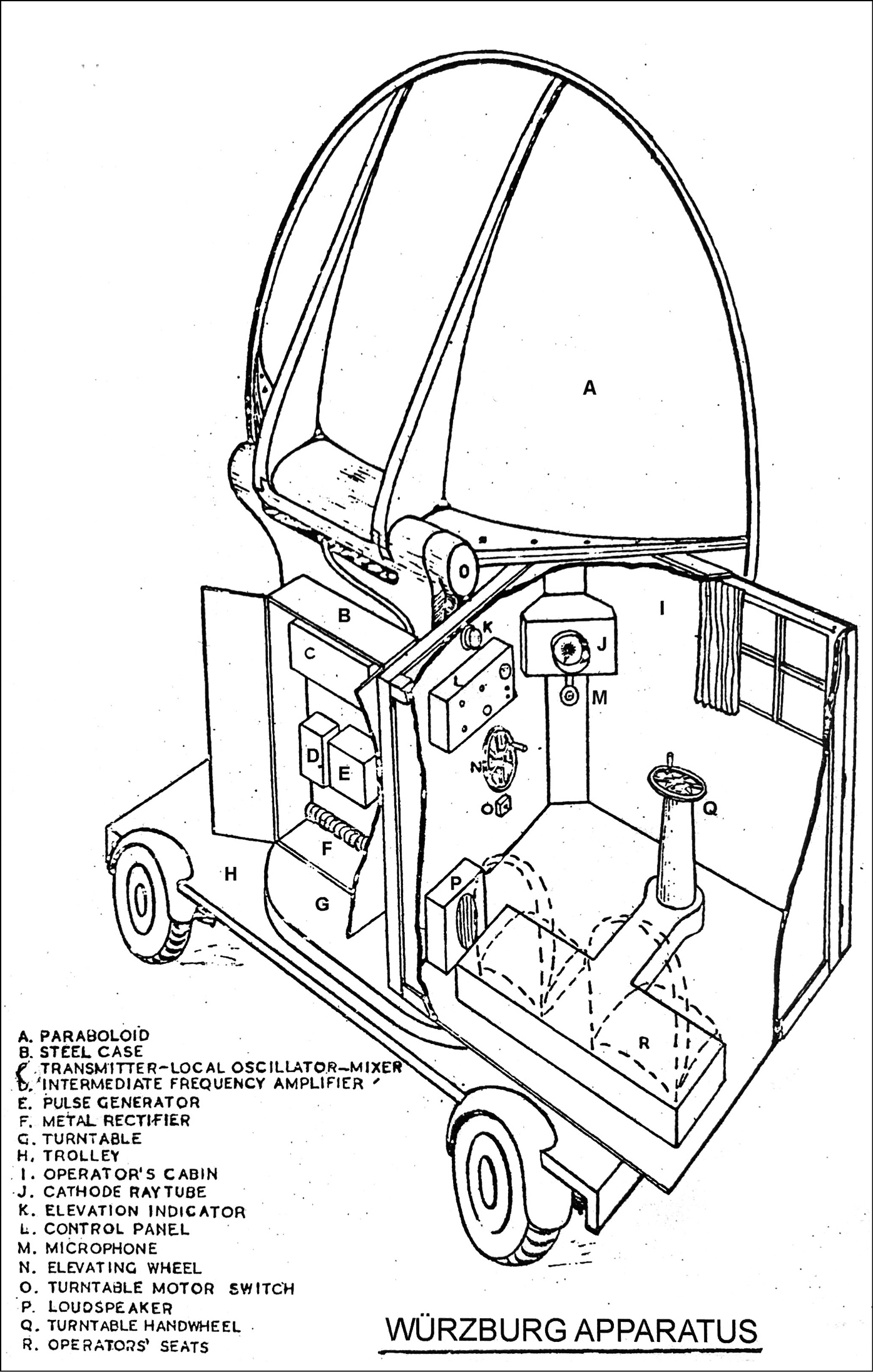

They discovered the set was mounted on a turntable bolted to a flatbed four-wheeled truck, surrounded by sandbags up to platform level. Cox said: ‘I found it to my surprise just like the photograph.’ The flight-sergeant made hasty notes and sketches while the engineers wrestled with the steel casing, five feet high by three wide and two deep. The airman scribbled: ‘Top of the compartment taken up by transmitter and what looks like first stage of receiver. Large power pack with finned metal rectifiers occupies bottom. Between the TX [transmitter] and power unit 1 the pulse gear and the receiver IF [intermediate frequency]. Everything solid and in good order.’

Cox said later: ‘I thought it a beautiful job, and I’ve been in wireless all my life.’ Each unit was mounted in an aluminium box for easy removal and exchange. He pulled aside the thick black rubber curtain across the entrance to the control cabin, then said to Peter Walker, standing with their Luftwaffe prisoner: ‘Hey, Peter, this thing’s still hot. Ask the Jerry if he was tracking our aircraft as we came in.’ Yes, the Jerries had been, albeit not this particular Jerry.

Within seconds the Demounting party discovered that to accomplish anything they must use flashlights, which soon drew fire from Rectangle. This intensified when Vernon set about taking photographs with his Leica, each flash in the darkness provoking a new spasm of German shooting. It is unsurprising that the lieutenant’s images afterwards proved useless, and that most of the thirty-six bulbs which he had optimistically borne into battle went undischarged. Frost told the lieutenant to abandon an almost suicidal activity.

The Germans’ subsequent narrative stated: ‘The commandos were nevertheless prevented from proceeding with their attack on the Freya position. The remainder of the Luftwaffe Communications Station unit … took part in this action’, meaning that Lt. Ruben now had his men shooting towards the Würzburg site. The after-action report represented, of course, a complete misreading of events. Frost’s men never intended to attack the Freya site, nor indeed to overrun the Gosset farm. Happily for C Company, however, the enemy supposed otherwise, probably because within the farm buildings was a Luftwaffe signals hub, which employed by far the largest proportion of the personnel posted on the Bruneval sites, interpreting and transmitting the information about British aircraft and shipping received by the radar plotters.

Lt. Huhne, the army’s representative in La Poterie, had in the meantime led his own men through the darkness towards the Gosset farm – and met Bren and rifle fire from Timothy’s Rodneys. The Germans went to ground; shot hesitantly back; but made no attempt to press on towards Frost’s group. The soldiers, like the Luftwaffe, sustained their belief that the British must aspire to break through to the Freya and plotting station. Thus, instead of seeking to launch a counter-attack to save the Würzburg, the Germans contented themselves with defending the larger installations – with containing the British, not knowing the latter were entirely happy to be contained within the ground they held. The defenders sustained their delusions, and their firing positions, almost until C Company began to withdraw an hour later, while Naoumoff and his Drakes, together with the Rodneys, more or less literally kept the enemy’s heads down, though without inflicting losses.

It is an interesting speculation, to which no clues survive, whether Jones and TRE ever considered requesting C Company to include the Gosset farm among its objectives, because the communications centre assuredly held technical secrets. The initial plan for Biting called for the Drakes to work around the farm buildings and open fire from their northern side, creating a diversion in the opposite direction to that in which Frost’s assault groups would be deployed. This idea had been abandoned, because of the likelihood that a small British party could find itself cut off from the rest of the paratroopers. Meanwhile, to overrun the densely-populated buildings, albeit only two hundred yards from Lone House, would likely have proved beyond the powers of Frost and his men. The Gosset farm nonetheless served its turn that night, because even if the British did not endow it with any priority, the Germans did.

On the Würzburg site, while the British engineers’ flashing photo-bulbs and torches provided aiming marks for the enemy, they were firing persistently high, and the sappers stuck to their work. One of Vernon’s men used a hammer and chisel to remove Telefunken labels and multiple number codes from the radar set, to provide Reg Jones and his boffins with indications of German production rates. As for the electronic elements, they discovered that their tools, even the longest screwdriver, were ineffective. Instead, impelled by the mingled urgencies generated by adrenalin, fear and desperation, they began to wrench whole sections from the set by main force, thus securing the pulse units and IF amplifier. When the aerial in the 2.8-metre scanner dish defied them, Cox told a sapper to take a hacksaw to it. The vital transmitter in the cabinet resisted until, in desperation, the airman and Vernon seized its handles while a third man plied a crowbar. The set, together with its frame containing the aerial switching unit, tore free.

As the engineers laboured on Henry, from below Bruneval hamlet they could hear the stammer of a German – in truth, French – machine-gun in action, together with the matching clamour of Brens, which must be Ross’s. They were also catching constant exchanges of fire from the north and north-east – Naoumoff’s and Timothy’s men shooting it out with Germans in the trees fronting the Rectangle, and on the approach from La Poterie. The Rodneys encountered new evidence of German pusillanimity. A stand-by section of the 685th arrived in La Poterie, and was persuaded to set forth to join Lt. Huhne’s firefight with the British. These men retired, however, after letting off flares and receiving the contents of two Bren magazines, delivered by Pte. Dick Scott, although again without inflicting casualties.

Frost speculated that the missing stick of Rodneys, seen to have landed south of Bruneval, might by now have descended to support the Nelsons. Then a messenger arrived from Timothy, who reported that his fourth section remained absent, but that he and the other three groups were still at their agreed positions further inland; everything was going according to plan – they were holding the Germans at a safe distance – except that their 38 wireless was dead, and one man had been wounded. Frost sent a runner to Naoumoff, in front of Rectangle, telling him to pull back through the Würzburg site, shouting the password ‘Biting!’ as often as may be, to reduce the risk from friendly fire in a confused situation.

Naoumoff’s retiring section soon reached the company commander, who ordered the Drakes to descend to reinforce Ross. The lieutenant passed the shoulder then headed towards the beach by a virgin route that took his men somewhat west of Ross, slipping and sliding down the hill only a few yards short of the cliff, where the defile became as deep and steep as any railway cutting. Amazingly unnoticed by the Germans, he and his men gained possession of an empty trench on the north side. From that position they began tossing grenades towards the Germans, though Treinies’ section was too well sited, up the opposite face, to take any harm. The defenders still blocked the passage to the beach, but were now closely besieged, by much superior numbers. Sgt. Bill Sunley crawled towards Ross and shouted that he could shift the knife-rest gate in the wire, opening a path through which the Nelsons could advance, though covering the last yards to Stella Maris under fire would still be a hazardous business. There were lulls in the little battle in the defile, but every British movement prompted renewed German fire. Ross sent a runner up to Frost, to report that he and the defenders were still deadlocked.

Around Henry, German shooting increased. Lt. Huhne’s machine-guns now joined the one borrowed by Lt. Ruben, sending tracer arching two hundred yards across the night sky from the Gosset farm. In Frost’s words, ‘it became extremely uncomfortable in our area’. One burst of fire caught two unlucky paratroopers outside the château, killing Pte. Hugh McIntyre with a bullet in the head and wounding Corporal Jeff Heslop in the thigh. McIntyre, it may be recalled, was the twenty-eight-year-old Ayrshire man who had breached security a week earlier to write to his brother about the raid, promising he would be ‘home next Saturday … I’ll be seeing you next week’. Though most of the incoming fire remained inaccurate, a couple of rounds pierced the Würzburg dish.

The major now felt the full weight of the loneliness of command in action. He had no radio contact with any other party, and so knew only what was happening within his line of sight. He mutely cursed Browning’s staff, which had imposed the organization depriving him of the headquarters that customarily formed a key component of an infantry company. Sporadic gunfire was audible both north and south, and he noticed the lights of vehicles flickering behind the thick belt of trees screening the Gosset farm. As the minutes ticked by, he envisaged the Germans setting up heavy weapons: if they started to use mortars or artillery, the company would be in deep trouble. The engineers’ labours seemed interminable, though the use of jemmies in lieu of screwdrivers hastened progress.

At last, Vernon reported that he and Cox had extracted most of the key components of the Würzburg, which they had loaded onto the one trolley that seemed necessary. As German fire intensified, the major made an abrupt decision: they would pull out. They had a Luftwaffe technician as their prisoner, and most of the innards of the radar set. The engineers had enjoyed just ten minutes’ access to the installation, instead of the half-hour the planners intended, but the longer span had always seemed wildly optimistic. Their only significant miss was failure to seize the display on which the operator viewed incoming radar signals: they ran out of time before they could address the technology inside the little crew cabin.

Frost now faced his next big uncertainty: about what he and his treasure-hunters would face, on their half-mile descent towards the beach through the moonlight and amid erratic fire. They began trudging and trotting towards the scrubby hillside that led down into the defile which offered the only approach to the sea, paratroopers covering the trolley party who, despite the assistance of the five unarmed Rodneys, struggled with their eighty-pound load on rough turf covered with several inches of snow. Gerry Strachan, that pillar of strength who had always seemed indestructible, was moving a little behind Frost at the head of the Hardys and Jellicoes, just below the pillboxes on the crest occupied earlier by Sgt. Tasker and four Nelsons, when a burst of German fire from the south side of the defile – the trenches above Stella Maris, some two hundred yards distant – caught him. He fell with three Châtellerault bullets in the stomach. One of the engineers, Reg Heard, was also hit, in the hand.

The major dragged Strachan beneath the concrete lip of the casement approach. He jabbed a morphia syrette into the CSM’s abdomen, then administered field dressings to the wounds. While firing intensified in all directions, the sergeant-major, delirious, began to shout incomprehensible orders. Frost ordered the engineer party to go to ground with their precious burdens until the enemy fire was suppressed, the path opened to the beach.

The paratroopers had triumphantly accomplished the purpose of their operation; done the job which Reg Jones had asked of them. Yet now they faced the further vital challenge: to get home. Everything thus far would have been in vain if they could not carry their booty safely to the beach, and make the rendezvous with the navy. And at that moment, the way to escape was barred by a handful of Germans who proved the only enemies that night to display determination and courage in confronting the airborne invaders.