A Gentle Revolution

On a Sunday evening in February 1870, a young journalist, Muḥammad Unsī, sat in one of the seats of the Khedivial Opera House. He watched the opera Semiramis. He immediately grasped that there was a connection between theater, language, and patriotism. “Oh, if such refined works were translated into Arabic successfully,” wished Unsī in a review he wrote about the performance, “and they were performed in the Egyptian theaters in the Arabic language as an innovation, that the taste [for theater] may spread among the local (ahliyya) groups. Because this is the sum of the patriotic (ahliyya) components that facilitated the advancement of the European countries and helped to enhance their internal conditions.”1

This chapter examines how intellectuals—in the Arabic press and in the Arabic theater—reacted to the spatial and sensorial transformation of Cairo and the work of the khedivate. The intellectual production within or associated with government circles constituted what I term a “gentle revolution.”2 This includes the use of the learned Arabic language (al-ʿarabiyya al-fuṣḥā) as official language of the khedivate and the retelling of Muslim history of Egypt as an Arab narrative. The keyword of this process was “the homeland” as a political argument.

A very short, gentle epistemological revolution occurred between the mid-1860s and approximately 1873. As an example of the gentle revolutionaries I follow the activity of ʿAbd Allāh Abū al-Suʿūd in this period, who printed al-Ṭahṭāwī’s Marseillaise in his 1842 book. His son was no one else than Muḥammad Unsī (d. 1885/1886), the journalist in the opera house. Abū al-Suʿūd and Unsī were genuine thinkers and belong to the nineteenth-century vanguard of Arab intellectuals. Their story, and their important printing press and journal Wādī al-Nīl, in turn, serve as the backdrop against which we can measure the activity of other intellectuals who became famous despite their actual insignificance, such as the writer James Sanua. The story of Sanua’s hasty, failed Arabic theater troupe can be seen as a competing project with Unsī for defining the content, or, direction of patriotism. Unsī’s was a vertical imagined community while Sanua’s was a horizontal construction. These imaginations clashed with each other almost invisibly behind the khedivial façade. Let us first examine the making of vertical patriotism in Egypt.

FUṢḤĀ ARABIC AS THE LANGUAGE OF POWER

Abū al-Suʿūd and Unsī were parts of a loosely defined group whose activity was related to the khedivial government and should be seen as the first attempt by local intellectuals to use government resources for reform. They are the ones who synchronize the imagined Muslim past with new spaces of power through print, education, sound, and language. What seems to unite these intellectuals was an unspoken but shared belief that educated Arabic, al-ʿarabiyya al-fuṣḥā, should become the language of the khedivate. They did not exclude the use of the vernacular for specific functions. But the vernacular was not useful to compete with European aesthetics and for negotiation with a Muslim sovereign because it had no textual historical dimension.

Making Arabic the language of power happened, in fact, officially. True to Benedict Anderson’s argument that dynasts adopt “some vernacular as language of state,”3 Ismail declared Arabic (al-lugha al-ʿarabiyya, undoubtedly the administrative version of fuṣḥā Arabic) the official language of the administration in 1870, instead of Turkish. Turkish remained important: in 1868 Ismāʿīl Ṣiddīq “al-Mufattish” still requested Turkish clerks in the governorates,4 and army leaders asked for and were granted an exemption in 1870.5 The administration of the island Taşoz facing the city of Kavala also continued to be conducted in Ottoman Turkish; and this language was taught in (military) schools until the twentieth century. However, it seems the khedive and Muslim intellectuals agreed in this period that learned Arabic was the official language for the khedivate. Is it possible that this happened because they shared only two features: Islam and the fact that their mother tongue was different? European Orientalists looked at Egyptians as Arabs. For instance, Ignác Goldziher in this period thought that “national literature” in Egypt is “Arab literature.” Ismail was happy to satisfy Orientalists by ordering printed editions of Arabic manuscripts.6 Typically, Arabic-speaking Christians and Jews also favored this language. A rabbi in Alexandria in 1862 thought that Arabic is the purest language.7 “Pure Arabic” embodied a middle ground since it did not belong to anyone.

Khedivial Education as a Result of Compromise

The making of official Arabic was a common effort by local Muslim intelligentsia. This is where we can see the compromise of the 1860s at work. From the mid-1860s, a number of institutions were created that accorded a special place to the learned Arabic language, and in which its teaching and use were controlled centrally. Between 1867 and 1873, in changing functions, ʿAlī Mubārak dominated the Department of Education (Dīwān al-Madāris); Dykstra convincingly suggests that his policies were also influenced by the new Chamber of Representatives.8

Mubārak executed, to some extent, the wishes of the aʿyān and shuyūkh, in the new, small but significant network of government schools (next to the thousands of village Koran-schools [kuttāb], which also came under government control after 1867);9 the Khedivial Library (1868), a new college to train teachers, Dār al-ʿUlūm al-Khidīwiyya (1872, in French called the École normale); and a school for girls (1873). Yet, most of the specialized government schools trained Egyptians for military or bureaucratic service,10 with some notable exceptions such as the School of Egyptology. The gentle revolution starts in these spaces.

In the khedivial schools, old sciences such as Arabic grammar, poetry, Muslim theology and law, and new ones, such as engineering and chemistry, formed a plural, hybrid core of modern, patriotic knowledge. Islam remained part of education in a re-Ottomanized form; for instance, only ḥanafī law was taught in Dār al-ʿUlūm, which became the dominant sharīʿa interpretation in khedivial Egypt (both the House of Osman and the Mehmed Ali family belonged to the ḥanafī school).11 Azharite sheikhs, however, resisted reforming their curriculum.12 Islam was important from another point of view as well. ʿAlī Mubārak was also Director of Religious Endowments (Awqāf), and it was in this capacity that he collected some waqf libraries in Egypt into one central institution, the “Khedivial Library” (Dār al-Kutub al-Khidīwiyya; often called in rather Ottoman Arabic al-Kutub-khāna al-Miṣriyya [the Egyptian Library]).13 Although the library also received donations from abroad, its foundations were the waqf libraries; books (manuscripts and prints) that the wealthy in Ottoman Egypt had collected and donated for education. While centralization represented an intervention in Islamic law (waqf is nonalienable), at the same time, because the central library served educational purposes, and was open to “everyone,” it preserved at least the donors’ intentions. Yet as a result, the supervision of knowledge passed into the hands of the government.

As for the students, a government publication in 1873 mentions 2665 schools in which a total of 96,141 students studied, out of which only 3,699 studied in the new “civil” schools. In this calculation “civil” includes military schools and primary schools as well.14 There is another estimate that 4,817 schools functioned in Egypt in 1875, of which 4,685 were the traditional Koran-school (kuttāb) and only nine were graduate, “civil” college-like schools,15 but in addition to military and missionary schools, the student missions in Europe, and the mosque-university al-Azhar. There were new styles of learning too, such as a lecture hall (“amphitheater”) open for public lectures in the main “hub” of education, the Department of Education (the former palace of Mustafa Fazıl, called Darb al-Jamāmīz);16 the first khedivial library, in the same building, was also open to the public. Young Azhari students were attracted to new knowledge through these lectures.17

Fuṣḥā Arabic for Khedivial Praise in Schools

The few but significant schools—even in the 1890s only 4.8 percent of the total population could read and write18—were sites of an unprecedented experiment with education in the Egyptian province. It would be unjust to reduce the fascinating production of knowledge, the sensitive balance between Muslim sciences and Western technology, and the openness of Muslim intellectuals in this period to the story of patriotism in Arabic. The first Copts as public figures also appear at this time. Nonetheless, the teachers and students had to participate in the praise of the absolute ruler, as they had during the reign of Mehmed Ali.

The makers of patriotism cherished fuṣḥā Arabic both as a patriotic and as a moral value. ʿAbd Allāh Fikrī, the Arabic teacher of Ismail’s sons, his secretary for Arabic correspondence, and later director of education, wrote in these years that “the best language in the world and the most brilliant one in which the human race ever talked . . . is the language of the Arabs.”19 This is perhaps not surprising if we note that he hailed from a noble family of ʿulamāʾ.20 He became subdirector in 1871 at Dīwān al-Madāris and later its minister. Indeed, one wonders whether it was due to ʿAbd Allāh Fikrī’s hidden influence on Ismail that Arabic became the official language of the administration.

The schools essentially served as the prime sites through which patriotism became an ideological tool that accompanied the acquisition of knowledge in Arabic. ʿAlī Mubārak’s department of education employed Ṣāliḥ Majdī (who was the wakīl of the ministry), and old al-Ṭahṭāwī himself, both writers of waṭaniyyāt. The exams and end-of-the-year celebrations were public occasions attended by the “princes” (often Tevfik, the heir presumptive),21 where, as ʿAlī Mubārak once wrote to the khedive, “the students can demonstrate in front of the noble zevat, the most learned ʿulamāʾ, and the esteemed merchants what they have learned from the sciences and arts in the shadow of his Highness the Khedive.”22 On these occasions, al-Ṭahṭāwī and others gave speeches in fuṣḥā Arabic, as had been the habit in the 1840s. The printed speeches23 attributed success to both divine providence and Ismail, as in the declaration that “God opened the gates of knowledge by the khedive of Egypt.”24

At the same time, however, multilingualism continued in everyday life. The teachers spoke versions of Egyptian Arabic as their mother tongue, and they often knew some Italian and French, as well. In addition, elites close to the khedivial household, such as ʿAbd Allāh Fikrī or Ismāʿīl Ṣiddīq, were fluent in Ottoman Turkish. Alongside the official projection of monolingualism, then, there was everyday multilingualism in all social circles.

PRINT ENTERPRISES AND MUSLIM AESTHETICS

Besides new spaces and pictorial images, the khedivial government used first the non-Egyptian press for the pasha’s public image. This image was designed as an external one. We have seen that Said and Ismail in the 1850s and 1860s financially supported Ḥadīqat al-Akhbār in Beirut, al-Jawāʾib, Turkish, and French journals in Istanbul (Ruzname-i Ceride-i Havadis received yearly support even in 1870; the editor of Basiret in 1877; and the Levant Herald throughout the 1870s), and a number of French journals in France. This shows that the pashas in Egypt, like the Ottoman imperial administration, were aware of international (and imperial Ottoman) public opinion as a powerful means in politics.25

Within the province, in 1866, a Press Office (Jurnāl Kalamı in Ottoman Turkish) containing five censors (including a Turkish officer) and led by a certain Trabi Efendi was established in the Department of Foreign Affairs.26 It was established in that department because at the time permissions to start journals were given mostly to foreign subjects. There were Italian, Greek, and French private journals and presses.27 The private Arabic lithographic and printing presses in Cairo and Alexandria were supervised by the governorates and the Interior Ministry, and sometimes asked the opinion of the grand mufti, but those presses did not produce periodicals at the time.28 (See more in chapter 7 on later censorship.) These measures were part of a general effort in the 1860s to assert control over European activity in late Ottoman Egypt.

At this time, a new “national” printing press was also imagined. There is an unsigned proposal in French in the Egyptian Archives possibly from 1866 that proposes an Imprimerie Nationale Égyptienne, the main purpose of which was to emphasize sovereignty and save money for the government (which had documents printed in various languages by firms in England or France), reasoning that “a government cannot trust its projects on a private printing press.” The project contains the unification of the French press of Antoine Mourès in Alexandria (after purchasing it) and the press of the État-Major (Department of War) in the Citadel, and suggests a staff of fifty-one persons. Even the text of a contract between Mourès and the government was prepared regarding the acquisition of machines and typefaces, and appointing him as director.29 There is no evidence that the press was ever established.

THE MUSLIM PRESS AND ARABNESS IN EGYPT, 1866–1873

The early Arabic press is often considered to have been, exclusively, a means of social mobilization that helped the ʿUrābī revolution.30 In contrast, others, such as Ami Ayalon, suggest that Ismail used the first Arabic journals in Egypt for propaganda.31 Here, I rethink these contradictory claims by examining early Arabic journalism as both a business enterprise and part of the complex mechanism of Arab patriotism. The periodicals functioned as interfaces between khedivial interests and interests of Arabic-speaking intellectuals.

Between 1866 and 1873, there were only three regular Arabic periodicals printed in Egypt: Wādī al-Nīl (The Nile Valley, 1867–1872?), Rawḍat al-Madāris al-Miṣriyya (The Garden of Egyptian Schools, 1870–1877), and the government bulletin al-Waqāʾiʿ al-Miṣriyya (Egyptian Events, 1828–today).32 There were some ephemeral private Arabic periodicals. In May 1870, a short-lived commercial periodical, al-Munbih al-Tijārī al-Miṣrī (The Egyptian Commercial Gazette) was printed in Italian and partly in vernacular Arabic in Cairo (see below). Another commercial publication was Jūrnāl ʿUmūmī li-Kāfat al-Iʿlānāt, printed by the Castelli Press in 1872. The elite Egyptian Ibrāhīm al-Muwayliḥī also printed, with his own press, the journal Nuzhat al-Afkār (The Promenade of Ideas) in August 1870; it was discontinued (possibly banned) after only two issues, which are now lost. These were all Cairo-based periodicals. From 1873 on, the center of Arabic journalism moved to Alexandria due to new Ottoman Syrian enterprises.

The primary goal shared by the early Cairo journals was the dissemination of old and new types of knowledge, including a great concern with fuṣḥā Arabic and Islam, and government propaganda, as opposed to the later more capitalist underpinnings of the Arabic press.33 Some of these early journals, like Wādī al-Nīl, were also part of printing businesses which aimed at profit. Yet they were not “journals” in the sense that we think of them today as a means to transmit news to the public as an economic activity and as a check on governments. They rather represent an intermediate stage between old and new regimes of public knowledge; their activity created a form of modern Muslim memory through printing and serializing selected medieval works. They created classics and themselves became classics.

I contextualize and rethink the activity of the two core Muslim periodicals Wādī al-Nīl and Rawḍat al-Madāris in this section. Their distribution was limited (a couple of hundred copies each), but given the oral culture in Egyptian streets, they may well have reached a much wider audience. A German traveler in 1870–1871, for instance, noted that Wādī al-Nīl was read aloud among groups of men “in the coffeehouses, at public fountains, and in the mosques” and had an “influence.”34 Reading journals aloud in streets is a familiar trope that is often repeated later. The papers also represent much wider projects than a journal. I call them “enterprises.”

The Wādī al-Nīl Enterprise

The first private Egyptian Arabic periodical, Wādī al-Nīl (The Nile Valley), was published in July 1867, through its own Arabic printing press, just a few weeks after the Ottoman firman of the khedivate. Some believe that it was the khedive’s instrument.35 Ibrāhīm ʿAbduh, the great press historian, ambivalently judges that “the idea for its establishment was the loyal service of the khedive” but adds that “it was the first national and popular periodical in Egypt.”36 Sadgrove differs, arguing that it was an “independent newspaper,”37 Cole suggests that government donations “did keep subscription and newsstand prices down,”38 and Barak terms it “semiprivate.”39

In fact, ʿAbd Allāh Abū al-Suʿūd funded the journal at great sacrifice without government involvement. The khedivial secretary ʿAbd Allāh Fikrī hoped that Ismail Pasha would help Abū al-Suʿūd since, Fikrī argued in a letter to the khedive, this first popular (ahliyya) journal furthered patriotic progress.40 The government bulletin celebrated its private “sister” journal, Wādī al-Nīl.41 Ayalon’s claim that Abū al-Suʿūd was “hired by Khedive Ismail to edit a government newspaper”42 seems to be incorrect. As a response to Fikrī’s request, Ismail may have encouraged the journal, which later did rely on government resources and which was indeed loyalist, as this was the condition of public speech.

The journal Wādī al-Nīl must be seen as part of a larger printing business enterprise and a quite successful one. The printing house of the same name was a major producer of fuṣḥā texts. Abū al-Suʿūd and his son Muḥammad Unsī were both the editors of the journal and the directors of the press; the typeface was owned by Unsī;43 the whole printing house was owned by his father.44 Unsī had earlier owned, with his brother Aḥmad, a printing machine with Latin and Arabic typefaces in Cairo; the brothers’ only surviving publication is an archaeological essay in Italian in 1865, which contains images of half-naked female Greek sculptures.45 He also had a lithograph and published popular mystical and theological texts in 1867.46

As table 4.1 shows, the printing press under Abū al-Suʿūd’s and Unsī’s direction published around fifty titles, often in multivolume formats, and four journals, over approximately eleven years (the majority between 1867 and 1873). This is an estimate. Some military and economic manuals, so far unlocated, must also be added to this number, and serialized books in the periodicals. The journal Wādī al-Nīl worked in symbiosis with its printing press: it often advertised the books and their prices.47 There was also a bookshop, run by Muḥammad Unsī and Mourès, where the journal could be contacted, and where the press moved in 1869 for a few years.48 The press printed and sold selected linguistic and adab works (some of them were published in a serialized format in the journal); and religious texts such as Koran interpretations. It also published calendars.49 It printed various materials: an Arabic primer,50 the translations of the Egyptian Museum catalogue in 186951 and of the librettos of the operas Les Huguenots52 and Aida in 1871,53 all by Abū al-Suʿūd; and a romantic Arabized novel, and the Arabic translation of Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo.54 The printing press, the journal, and the bookshop were elements of a real enterprise serving the owners’ own interests, as well as orders from the government and from private individuals.

In addition to its own journal, this press published three periodicals in the early 1870s: Rawḍat al-Madāris al-Miṣriyya, the official journal of the Ministry of Education, between 1870 and 1871 (this journal lasted until 1877),55 Jarīdat Arkān Ḥarb al-Jaysh al-Miṣrī, the official journal of the General Staff of the Egyptian army in 1873 (it then was printed at another press until 1879); and Unsī’s new journal Rawḍat al-Akhbār from December 1874.56

Evidence of the entrepreneur spirit is that Unsī and Mourès owned another press (or a typeface) together in 1869 that could print with French characters.57 The enterprise at the beginning seems to have been sufficiently successful that, in September 1868, a certain De Morely asked permission to establish an Arabic press in Alexandria and to similarly publish an Arabic revue (he was not granted permission).58 In early 1870, Unsī’s French typeface was destroyed in a fire, and he suspected that this “devilish act” (faʿliyya shayṭāniyya) was intentional, committed either by a foreigner or by a local Egyptian, possibly for business reasons or against the journal itself.59

The Wādī al-Nīl enterprise was close to the government. In 1869–1870 they printed librettos in Arabic at Draneht’s personal order.60 One should not forget Abū al-Suʿūd’s job in the Translation Office. This press may even have been shrewdly conceived as a private business, which awaited official orders to gain extra profit in the private printers’ competition for Arabic publications.61 Or was it a consequence of the draft project for an Egyptian National Press in 1866? Is this the reason why it also printed Jarīdat Arkān Ḥarb and books for the army? Abū al-Suʿūd and Unsī had access to news over the telegraph through the government, and thus their journal was the first to publish telegrams in Arabic. In 1870, their press also printed at least six books for the Department of Education, serialized in Rawḍat al-Madāris. It continued to work at a smaller scale until around 1878 when it was taken over by new owners.62

The journal Wādī al-Nīl contributed to patriotism in various ways, first of all by framing government news within a literary context in fuṣḥā Arabic. As fitting nation-ness, the title—the Nile Valley—alluded to a territorial attachment without defining exactly the borders or announcing a polity. In its available issues,63 it regularly published news related to the khedive, such as his attendance in the khedivial theaters, the marriage of his daughter in 1869, his movements, his charities, or even the public sale of khedivial horses. It also reported on Majlis Shūrā al-Nuwwāb; published the train schedule and announcements from the khedivial post service; and often repeated those news items from al-Waqāʾiʿ al-Miṣriyya that the editors considered “patriotic” (ahlī, waṭanī), such as the results of school exams. The journal never printed critical reports from the foreign language press, although the editors regularly borrowed news from Italian and French papers.

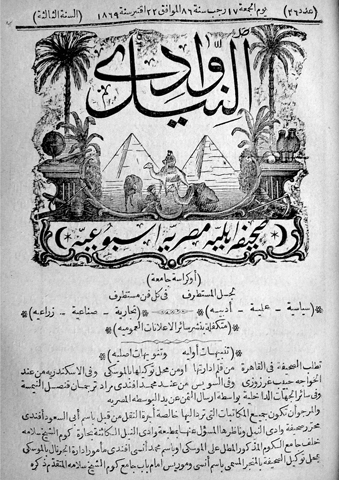

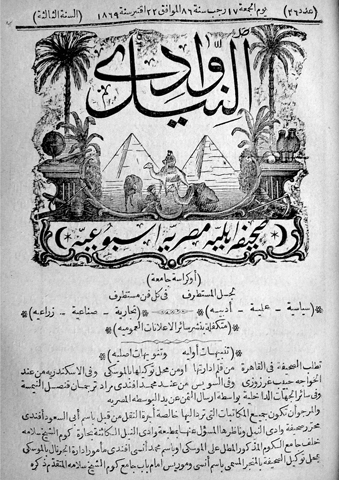

Its title page carried the first human images in Arabic journalism. An example from 1869 (figure 4.1) tells of an effort to bring together visually the various histories and features of khedivial modernism. We can see Ismail Pasha, presumably, on a camel, between two pyramids (pyramids had already been present in the title image of al-Waqāʾiʿ al-Miṣriyya), framed by two palm trees. At the front sits a man with two camels. At the base of the palm trees there are various instruments on both sides: on the one side perhaps representing agriculture and at the other possibly tools of navigation (technology). The great calligraphic title, Wādī al-Nīl, looms over the image.

FIGURE 4.1. Title page of Wādī al-Nīl journal, 22 October 1869

Source: author’s photograph.

Wādī al-Nīl could be bought in all the Ottoman Arab provinces, in theory even in Baghdad, while in Egypt in Cairo, Alexandria, Suez, and anywhere through the khedivial post. First, it was a weekly, then it was published two times a week, and from 1871 again weekly (appearing every Friday).64 In 1869 the yearly subscription was 100 qirsh (36 francs), and one issue was 4 qirsh (1.25 francs); in 1871, when it changed back to a weekly, the price was lowered to 3 qirsh. These prices made the journal available to the readers of Arabic with modest income but certainly not to peasants and workers; although oral dissemination may have reached them. It was often quoted by al-Jawāʾib in Istanbul. Wādī al-Nīl was part of the Ottoman Arabic public sphere.

This patriotic product was a Muslim journal and represented a new form of Muslim cultural memory through careful selections. While the use of news from the telegraph brought epistemological confusion by the parallelism of the Hijri-Gregorian calendars this novelty may not vindicate Barak’s judgment that the journal “became one of the technologies that formed the worldview of the colonial subject.”65 Wādī al-Nīl created rather a new, aesthetic sense of Muslim culture in print, which was influenced by new communication systems and European practices. It carried on its title page a motto that it “contains a great selection from all elegant arts” (jāmiʿa li-jull al-mustaṭraf fī kull fann mustaẓraf), which was an allusion to the medieval adab collection of entertaining stories and poems spiced with ḥadīth and Koranic verses, by Shihāb al-Dīn al-Ibshīhī (d. 1446), who wanted to collect all fann ẓarīf, “the elegant and witty arts.”66 The surviving issues do not contain congratulatory poems or other forms of direct dynastic praise; rather, the journal’s main activity was delivering news and serializing adab works. It also published Unsī’s articles, such as the one about the opera with which we began this chapter. Certainly, Abū al-Suʿūd and Unsī’s patriotism was not a secular one—Muslim scholarship and the Koran figured prominently in their activity, as Koran interpretations were printed in their press. Their journal highlights the co-existence of Muslim ideas and nation-ness together as intertwined textual traditions.

Abū al-Suʿūd and Unsī did not perceive their activity to be an exclusive form of linguistic dominance via print-based patriotism. This much is clear from their reaction to the Italian–vernacular Arabic al-Munbih al-Tijārī al-Miṣrī in 1870. They noted that, although it is not in “correct” Arabic, nor in the “pure” Ḥijāzī Arabic [!], “it is not without benefit and elegance.” As Barak points out, they approved of the printed vernacular as useful in terms of providing the speed needed for commercial transactions.67 Their press also printed the vernacular translation of Tartuffe by Muḥammad ʿUthmān Jalāl (though with a fuṣḥā introduction). The ultimate purpose of Wādī al-Nīl was self-refinement—to make one’s self ẓarīf, an educated and entertaining gentleman by both Muslim Arab and contemporary French standards. One may also detect some European Orientalist influence here in the selection of serialized texts. Still, in this project vernacular products could be fitted in if their subject or goal was considered useful. Overall, the press made a spectacular production of texts and journals, and thus their forgotten owners, Abū al-Suʿūd and Unsī, had much more importance at the time than the many “great men” who were later canonized.

It seems that the journal Wādī al-Nīl was suppressed by the order of the government in 1872.68 Sadgrove suggests that it was only suspended for a time, and continued to be published at least in 1875.69 Abū al-Suʿūd worked as a senior translator at the Translation Bureau, but in 1872 he was appointed the leading history teacher at the newly established Dār al-ʿUlūm, and was also promoted to head the Translation Bureau.70 He received the one-time sum of 280 LE in 1872, an extraordinarily high amount.71 His son Unsī’s new journal certainly also received financial support from Ismail in 1875.72 The historian Mohamed Sabry remarks that Abū al-Suʿūd defended Khedive Ismail until he died in 1878.73 As we shall see below, the journal’s suspension and Abū al-Suʿūd’s appointment in 1872 were perhaps connected. The press itself was taken over by others after 1878, and after 1882 there is no publication in its name.74

The Rawḍat al-Madāris Enterprise: Cairo as Abbasid Baghdad

The second enterprise clearly included an effort to make patriotism the ideology of the khedivate in schools. Rawḍat al-Madāris al-Miṣriyya was a government publication, appearing first on April 16, 1870, to be distributed among teachers and students in both the reformed schools and the new ones. For this reason, it featured more khedivial praise than Wādī al-Nīl.75 Edited by ʿAlī Fahmī, al-Ṭahṭāwī’s son, it was the organ of the new system of education, and connected with the new Khedivial Library,76 about which both Fahmī and ʿAlī Mubārak wrote in the first issue. Mubārak in his article connected the library to the “freedom” that Egyptians now enjoyed under Ismail’s reign.77 Soon it was printed by the Department of Education’s own printing press, which also published educational texts for school use. This project was a government branch’s enterprise for the distribution of knowledge and patriotism.

Rawḍat al-Madāris played a crucial role in connecting intellectuals in the new schools, and outside of them, by distributing information and organizing intellectual contests around puzzles. It often framed its articles as being in “the service of the homeland.” Among its authors were Copts who seized upon the forum to step onto the stage as patriotic intellectuals. It was more scientifically and technologically conscious than Wādī al-Nīl. Its history is well-known;78 Hoda Yousef highlighted its significance for rethinking the construction of the categories “modern” and “traditional” knowledge.79 Here I point out the way it framed the khedive as part of official nation-ness.

The first issue was centrally concerned with presenting itself to the khedive and convincing him of the publication and its authors’ absolute loyalty. In addition to the aforementioned articles, it also featured panegyrics by Ṣāliḥ Majdī and the student Aḥmad Naẓmī, which were greetings sent to the ruler on the occasion of the new hijrī year (the issue was published in Muḥarram, the first Muslim month) and which also contained chronograms (the hijrī year 1287). As before, Muslim concepts remained part of Arab patriotism. Aḥmad Naẓmī thanked God for Ismail because he was “the khedive of Egypt and its Mighty One / its owner [or king: malīk] and sum of its pure gold, the scion of [its earlier] lover” (possibly Mehmed Ali).80 Subsequent issues also contained instances of such direct praise.

Rawḍat al-Madāris published diverse articles, some of which were quite personal, such as the short, moving eulogy written by ʿAlī Fahmī after his father’s death.81 Yet even some of the more professional topics were connected to khedivial authority. Abū al-Suʿūd, for instance, translated a treatise on education from French, in which he praised Ismail for establishing Dār al-ʿUlūm (in the article mentioned as Dār al-Muʿallimīn).82 This happened after the legendary closure of his own journal in 1872. In fact, the entire end of Dhū al-Ḥijja 1290 (February 1874) issue was dedicated to Ismail, with Abū al-Suʿūd’s essay followed by Tādrus Bey Wahbī’s panegyrics celebrating three marriages within the dynasty and ʿAlī Fahmī’s poem for that occasion (see below).

The revival and reinvention of the Muslim past as an Arab one, connected to a strong sovereign, was central to making discursive nation-ness. Through the dissemination of loyal patriotic speeches Rawḍat al-Madāris contributed to a general sense of cultural revival. The cultural life of Baghdad in the ninth and tenth centuries, during the Abbasid Empore, seems to have served as a reference point. The speeches of al-Ṭahṭāwī usually contained poems; for example, there was this speech in June 1870: “And after giving thanks to God: indeed the progress / is firmly established in Egypt / arts make Ismail happy / he renewed an age, the time of trust! / and by him indeed Egypt became Baghdad / but the sciences of the Egyptian age are more / the beauty of Paris and the pride of London / the rich and the mighty traveled to Egypt.” 83 The poem actually announced the first Abbasid symbol of Egyptian modernization.

In sum, the available information suggests that the gentle revolution attempted to build patriotic culture through the government. When we look at the attention of Egyptians in high positions (ʿAbd Allāh Fikrī and ʿAlī Mubārak) to the needs of Abū al-Suʿūd, his press, and Rawḍat al-Madāris, we see not some kind of khedivial plan, but an effort on the part of learned bureaucrats to convince the khedive of their “patriotic service.”84 This was a clever manipulation of khedivial needs for a pre-emptive response to the critical European press.85

DEMOCRACY IN THE KHEDIVATE

History teaching, like the Arabic press, presented both a blessing and a curse for the regime. History was the core of nation-ness and was also one of the primary ways in which the ruler could be bound together with the notion of the homeland through narration.86 History, however, facilitated regime-type comparisons that could potentially undermine authority. Indeed, I suggest that comparative history caused the fall of Abū al-Suʿūd and the closure or suspension of the journal Wādī al-Nīl.

Abū al-Suʿūd was appointed as teacher of history in Dār al-ʿUlūm in 1872. He immediately wrote and printed The Complete Course in Universal History because there were no books to teach history (he does not seem to notice al-Ṭahṭāwī’s earlier work). Abū al-Suʿūd was arguably the ideal person for this task, as a devoted Muslim who had studied at al-Azhar, but who also translated Mariette’s ancient Egyptian history, Aida’s libretto, and French geography. His book is a mixture of translations from European histories and original passages from Arabic books “in the khedivial courtyard,” as the subtitle adds in large characters. The book is humbly credited as “collected and Arabized” by Abū al-Suʿūd. The intended audience was mostly Muslim students from al-Azhar who were the student body in Dār al-ʿUlūm.87

The Complete Course in Universal History was an original achievement. The book mixes French historical theory and Egyptology with Arabic linguistics, ḥadīth, medieval Muslim historians (Ibn al-Athīr, Ibn Khaldūn, et al.), Arabic poetry, and Abū al-Suʿūd’s own ideas. He certainly followed al-Ṭahṭāwī’s earlier discussions of European political forms and likely had first-hand experience in Paris (he visited the city, but it is not clear when). The book had to serve as both his own and his graduates’ teaching material. This is the reason why there are exam questions on the content following each chapter. Al-Dars al-Tāmm could function as a teach-yourself-how-to-teach-history manual.

At Dār al-ʿUlūm the subject was histoire universelle, as opposed to other schools.88 This time, the homeland is clearly the Nile Valley. Abū al-Suʿūd wanted to write a history of the Egyptian nation (al-umma al-miṣriyya) within a universal history, comparing Egypt to other nations, with a special place for the dynasty. He praises the amazing power of electricity and the telegraph. Ismail is evoked in the preface with the usual praise; for example, he is described as “the first missionary (dāʿin) leading in the path of civilization and happiness.”89 The khedive also figures among the definitions of the word tārīkh (“date,” “history”) when Abū al-Suʿūd shrewdly describes the use of chronograms with the example written to celebrate the change of the succession order in 1866: “‘Ismail’s clan inherits Egypt’ makes the year 1284” (yarith Miṣrā [!] Āl Ismāʿīl sanat 1284).90 This is the only indication of Egypt’s Ottoman attachment.

However, we do not know how he would have written about Egypt’s place in the Ottoman Empire. Al-Dars al-Tāmm, despite the obvious effort to please the khedive, seems to have been censored. Only the theoretical introduction and six chapters of ancient history remain out of the planned twelve chapters. All surviving copies that I was able to access stop abruptly at the beginning of chapter 7, third part, on page 400. We do not even know whether the book was actually taught in Dār al-ʿUlūm, although the truncated text was printed in several copies.

The introduction is a general methodology of history with a theory of politics, surpassing al-Ṭahṭāwī’s canonized earlier work. It contains the comparison of three regime-types: monarchical (mulūkiyya), aristocratic (al-ḥukūma al-aʿyāniyya), and popular (al-ahliyya) government. This last one Abū al-Suʿūd calls democratic (dīmūkrāsiyya): “[in this regime type] the administration of the resources of the community (milla) is in its own hands, I mean, it rules itself without the control of a king, a sultan, or a group of notables.”91

Abū al-Suʿūd also explains that, theoretically, a country’s regime expresses its “system of sovereignty or power” (niẓām al-mulk aw al-sulṭān), and constitutes, together with the laws and customs of the people, its “civilization.” He draws a distinction between two subtypes of monarchical government (al-ḥukūma al-mulūkiyya): absolute and constitutional (al-muqayyada aw al-qānūniyya). He then briefly adds another distinction, noting that a monarchy can be inherited in a family or be based on election.92 This sentence provides the first direct clue that Egyptian intellectuals saw the consequences of changing the succession order in 1866. The notion of election, in fact, was not new: there were texts in Arabic about election of kings, and Salāma Muṣṭafā al-Najjārī’s 1863 history also contained the notion of elected kings. After all, it was well known that the first caliphs of Islam were elected, too.

Abū al-Suʿūd’s work has a strikingly different approach to power than the short booklet of al-Ṭahṭāwī for disciplining students published in the same year in the Wādī al-Nīl press. Al-Ṭahṭāwī there explains that rulers in theory should obey the sharīʿa and the consensus of the ʿulamāʾ “but in reality, the order of the ruler (ḥākim) is compulsory.”93

We should not forget that in France the Second French Empire fell, the Commune was defeated, and a new republic emerged in 1871–1872. Abū al-Suʿūd (as al-Ṭahtāwī) was fluent in French and had access to such news; he may have visited Paris in this period. I suspect that this book and the general turbulence in France was the reason his journal Wādī al-Nīl was shut down in 1872. An additional reason may be that Abū al-Suʿūd was attacked by some ʿulamāʾ for his translation of a French geography, published in serial format in Wādī al-Nīl, which described the Earth as round.94 His son Muḥammad Unsī, as we shall see soon, had his own fight in 1872, although on a different front.

Marriage and Poetry: Ismail as “The Father of Arabs”

While the press and history carried potential subversion, poetry and rhythmic prose continued to fuse dynastic praise with patriotism. Sheikh ʿAlī al-Laythī took over the role of the leading poet from the deceased Muṣṭafā Salāma al-Najjārī in 1870. Al-Ṭahṭāwī and Majdī continued to regularly praise Tevfik,95 and Ismail96 in poetry, but we do not find poems from Abū al-Suʿūd. Fikrī was responsible for the khedive’s correspondence in Arabic with Arab sovereigns such as the sultan of Morocco or the leader of the Sanūsī order, and, of course, also composed congratulatory poems.97

Arabic poetry was featured on dynastic occasions such as the reception of sultanic firmans, marriages, and circumcision ceremonies. With regard to marriages specifically, there were two particularly noteworthy occasions of multiple weddings in 1869 and in 1873. The first was the wedding of Tevhide, the favorite daughter of Ismail, and Mansur Yeğen Pasha in the spring of 1869; at approximately the same time, the marriage of Zübeyde (a cousin of Ismail) and a rich zevat Ali Celal Pasha was also arranged. The second occasion was a giant dynastic union, four marriages in three weeks in 1873. Three sons of Ismail (Tevfik, Hüseyin, Hasan) and his daughter Emine married their cousins. As Kenneth Cuno argues, the introduction of endogamy—not an Ottoman custom—into the ruling family also imposed monogamy on the males since the marriage to a “princess ruled out the additional wives due to her standing.”98

The reason of dynastic monogamy was political. Ismail had already expressed to the French consul in 1866 that “it is dangerous to have many children of the same age. It would be important to prevent the rivalries of the harem.” Therefore, reports the consul, Ismail “started to look for men who know the Koran well and thus can help to create a new law by which he could force his children to have only one legitimate wife.” A committee of twelve religious scholars in Cairo declared that monogamy was not contrary to the Koran. A similar committee was to be formed in Alexandria and, if they also approved Ismail’s plan, the approvals were to be signed by all sheikhs and then presented to the sultan. The move to monogamy was regarded by the French consul as a step forward in “civilization.” 99 Although no such law was finally drawn, it is noteworthy that Ismail consulted the religious establishment and intended to have the approval of the local Egyptian notables and the sultan. This reflects the nature of the khedivate, and the imagined compromise between khedive and subjects. Yet, instead of legal means, the 1873 weddings were occasions for such public approval by symbolic ones.

ʿAlī Fahmī published a long congratulatory poem on the khedivial marriages in 1873,100 as well as a short booklet of patriotism, Tasting the Branch in Its Root through the Love of the Homeland and its People,101 which celebrated yet another firman reaffirming the privileges of Ismail in the same year. In Fahmī’s wedding poem, Ismail, the Ottoman governor, is described as “the father of Arabs” (Abū al-ʿArab).102 As to the celebration of the 1873 firman, using ample chronograms, Fahmī thanks God for giving Ismail and his sons to Egypt and prescribes gratefulness to Ismail for every “sensible person” since “the Ismailite state of the Mighty One” (al-dawla al-ʿazīziyya al-Ismāʿīliyya) was reaffirmed “in the light of the greatest caliphate” for “both general and individual benefit.”103 This small poem together with al-Ṭahṭāwī’s Baghdad-Cairo parallel intended to naturalize the khedivate and Ismail in an “Arab” romantic revivalism.

There were other individuals who were not connected to the patronage systems, such as one young man of extraordinary literary talent, ʿAbd Allāh Nadīm (1843–1896), who worked as a telegrapher in the palace of Hoshyar Hanım, Ismail’s mother, during the gentle revolution. He would later go on to have a much more important role in the ʿUrābī revolution. But during the spring of 1873, perhaps at the last moment when Egyptian intellectuals may have seen Ismail as a potential monarch, Nadīm wrote a long fuṣḥā poem celebrating the khedivial weddings. Nadīm sent the long poem to the editor of the official bulletin, with the title “To Serve Kings Is to Praise Kings” (Khidmat al-Mulūk Fī Tahāniʾ al-Mulūk) but only a few strophes were printed.104

Finally, the first significant zevat poet in Arabic publically appeared in the person of Sāmī al-Bārūdī (1835–1904) who, next to his military appointments, also praised Ismail Pasha in Arabic in the 1860s. He undoubtedly recognized his power in panegyrics, in one especially addressing the pasha he wrote: “you have been blessed with kingship.”105 His and Nadīm’s further political actions, which contradict to their early poems, are discussed in the next chapter. In sum, in the early 1870s an extraordinary production of printed texts aimed at fabricating an Arabic image of Ismail Pasha, while patriotism gained solid territorial contours.

SPACE AND LANGUAGE: PERFORMING PATRIOTISM

How could ideas become a communal experience and feeling? While patriotic projects identified the khedive and the homeland in print Arabic, Ismail and Draneht built a very different spatial aesthetics of power (see chapter 3). Muḥammad Unsī’s demand for Arabic plays in the khedivial theaters in February 1870 is the first public sign of the recognition of the discrepancy between the two projects. Space and language had to be synchronized.

Unsī demanded Arabic translations of plays and not original works. The reason for this is possibly the acknowledgment that (Ottoman) Arab mimetic entertainment was not efficient for learning modern patriotism, since it lacked the historical dimension. Farces and karagöz (in Egyptian Arabic arāghūz) were oral, vernacular genres that typically mocked the powerful or criticized society and had no engagement with heroic narratives.106 Patriotism needed modern, historical plays that could be presented to the khedive. While Aida was intended by Ismail and Draneht to be a “national” opera in Italian, local intellectuals sought to create their own form of patriotic Arabic theater. One example is Muḥammad ʿUthmān Jalāl’s “Egyptianization” of Tartuffe, which, in fact, starts with a few fuṣḥā Arabic lines remarking that “plays (tiyātrāt) are made for learning and refinement” and, after the vernacular play, ends with the compulsory fuṣḥā praise of the khedive.107

The educated Muslim vision of theater is perhaps best characterized by the didactic novel ʿAlam al-Dīn by ʿAlī Mubārak which was written in the early 1870s (but published only in 1882).108 He drew a clear distinction between “obscene and dull” traditional entertainment (awlād Rābiya and singers) and the civilizing effects of European theaters. This difference is explained, in the conversation between a British Orientalist and an Egyptian sheik, by the fact that the European (or British) actors and opera singers are trained and educated while the Egyptian street entertainers are not. The Orientalist explains that theater could be also useful for the rule of law (sharīʿa) and religion (diyāna), because it helps people to imagine “hell.” The sheikh does not find this point extremely convincing.109

ʿAlī Mubārak, through these characters, emphasizes the teaching function of theater: “it is a channel that stretches between the members of the nation (umma) and in which the water of science and scholarship flows from top to down, from the scholars and the elite to the ignorant and the ordinary.”110 This understanding of the modern theater, resembling the Syrian bourgeois theory of entertainment, articulated an elite turn away from street entertainment. But it did not exclude the use of the vernacular for characterization. ʿAlī Mubārak himself suggested the use of ʿāmmiyya in the first “Egyptianized” play of Jalāl. In Molière’s Le médicin malgré lui Jalāl had Egyptianized both the language (using an unrhymed Cairene dialect) and the plot (giving Arab names, etc.) because ʿAlī Mubārak had “instructed” him to do so.111

Importantly, theater needs both cultural and financial capital. A troupe needs actors to be trained, texts to be written, and stages to be created. These were not provided by Draneht’s cultural system, which imported all its elements from abroad except for the security guards. Unsī’s first solution was translation, and as a next step, as we shall see, the very logical demand for a school of acting. But someone else hastily created an Egyptian troupe, without training, relying on the tradition of Egyptian farces and Italian comedies instead of the learned adab tradition.

Marginalizing James Sanua

This was James Sanua (Yaʿqūb Ṣanūʿ, 1839–1912), who applied for government funds for a vernacular theater, almost completely misunderstanding the nature of the khedivial regime. Sanua’s comedies embody a type of patriotism that did not grow out of Muslim Arab traditions, directed by learned men, but imagined instead an urban vernacular culture as a horizontal community. It was doomed to failure and was a quite marginal enterprise compared to the projects by Abū al-Suʿūd and many others loosely associated with the government. Notwithstanding Sanua’s mistakes in many respects, however, his troupe did provide a platform that could be used by more sophisticated playwrights.

Sanua’s education was financed by Mansur Yeğen Pasha in the 1850s (Mansur Yeğen would marry Ismail’s daughter in 1869). In the 1860s, he worked as a language teacher and a poet, a typical middleman or “cultural creole,” to borrow Julia Clancy-Smith’s term.112 He wrote poems in Italian and was an Italian subject (his father was an Italian Jew from Livorno), but also spoke vernacular Arabic, while calling himself “James” instead of Yaʿqūb. In the late 1860s he became a member of a Masonic society in Cairo and, possibly through the Yeğen household, eventually became a partisan of Abdülhalim Pasha.113 In 1878, he started a satirical political journal, Abū Naẓẓāra (Abū Naḍḍāra in the vernacular) and was almost immediately exiled. Until his death, he published various journals in Arabic and French in Paris, confessing himself an Egyptian patriot, and an enemy of the British.114

I have already argued that Sanua’s troupe was an isolated, short-lived project that sought khedivial patronage and wanted to be seen as loyal.115 Here, I modify my interpretation to some extent. Although no information survives regarding the acting of the troupe, I suggest that Sanua’s comedies (but not the full repertoire of his troupe) may have been interpreted as subversive, even if this was not his intention. Thus the performances, partly in vernacular Arabic, may have posed a potential challenge to khedivial absolutism, especially in 1872, when Abū al-Suʿūd also printed a historical theory about various types of government. However, such a reading only makes sense when understood against the backdrop of the earlier engagement with theater in the gentle revolution.

Theater in the Khedivate, 1869–1872

Sanua’s troupe developed out of the theater craze in Cairo caused by the new khedivial theaters. Draneht sent libretti for Arabic translation and printing during the summer of 1869.116 Translations were also made, in larger numbers, into Ottoman Turkish, and even from Italian to French.117 The khedive paid for the journalist of Wādī al-Nīl to have a seat at the Opera among the European journalists during the first season (1869–1870). The journalist was Unsī, who later called for Arabic plays, as we have seen, in February 1870. In November the same year, Donizetti’s La Favorite and Rossini’s Il Barbiere di Siviglia were printed in Arabic by the press of Ibrāhīm al-Muwayliḥī118 and were sent to Wādī al-Nīl for distribution with an informal letter from the chief of police, allowing them to be printed. In the introduction, theater is held up as a means of civilization and progress. No translator is credited, so Wādī al-Nīl assumed it was Muḥammad ʿUthmān Jalāl.119 It is possible that this remarkable Egyptian translator and poet was thought to be the translator because of his previous association with al-Muwayliḥī (they co-edited the short-lived journal Nuzhat al-Afkār) and because his translation of La Fontaine’s tales was reprinted the same year.120

At the same time, in 1870, young Egyptians in Cairo wanted to stage a play entitled Alexandre dans les Indes, which had been translated into Arabic. We know this from the French report of a secret agent who called himself Agent Z. The agent attributed the desire of “the population” for theater in Arabic to a combination of recent events: a book of Arabic dramas printed in Beirut (probably Niqūlā Naqqāsh’s edition of Mārūn’s plays, Arzat Lubnān, 1869); a speech about Arab theater buildings delivered in Cairo’s New Hotel (probably by the architect Hector Horeau); and Arabic translations of libretti (“Don Juan, Moïse, Barbier du Seville”). One of these was among the libretti that al-Muwayliḥī sent to Wādī al-Nīl. The Qaṭṭāwī family, an Egyptian Jewish banker dynasty, also wished to stage Arabic dramas in their own house, possibly employing the same young Egyptians mentioned above, but had to postpone their patronage due to a family tragedy. Agent Z suggested to the government that it should support theater in Arabic with a view to educating the masses, by erecting a national theater building and une école filodramatique et musicale, as well as by introducing a copyright law [!]. In this suggestion, no distinction was made between fuṣḥā and vernacular Arabic. The project suggested by Agent Z would have served to “enlighten” the people, luring ordinary Egyptians to the theater rather than leaving them to “sing obscene songs” in the cafes. Thus, it was argued, theater in Arabic would usher in a new morality to khedivial Egypt.121

It is important to note that Unsī’s public Arabic and Agent Z’s secret French suggestions both framed Arabic theater as an instrument of progress. Both intended to reach the ears of the khedive. Their suggestions fit well with the imagination of Abū al-Suʿūd, Mubārak, and their colleagues. The belief in progress and in ethical purification through theater indicates that these suggestions were part of a general worldview. Unsī believed that theater in the “national” language was a key to progress in Europe and wanted the same to be established in Egypt. These utterances, from an educated Egyptian, and from a secret agent, highlight the connection between nation-ness and “progress” in learned patriotism.

Sanua himself was possibly encouraged by the fact that in the spring of 1871 the interregional Arab press also seemed, in different ways, to seek to convince the khedive of the necessity of an Arabic-language theater.122

Sanua’s Troupe as Part of Khedivial Culture, 1871–1872

In early 1871, James Sanua organized a theater troupe with some of his students. In all likelihood, their first public performance took place somewhere in Cairo on July 8, 1871, before a large audience. Al-Jawāʾib remarked that the Cairenes chose al-Qawwās, “an Englishman’s play,” despite the fact that Arabic plays from Beirut were available to them.123 On July 27, the troupe performed in front of Ismail in Qaṣr al-Nīl palace. They started with short pieces in vernacular Arabic written by Sanua, followed by the performance of two longer, more refined plays, al-Bakhīl and al-Jawāhirjī.124 The evening was arranged under the direction of Jamʿiyyat Taʾsīs al-Tiyātrāt al-ʿArabiyya (Society for the Establishment of Arabic Plays). James Sanua was the only member of this society mentioned in the press. There is no evidence as to whether the society was the same as the theater troupe that staged the performances. This evening performance before the khedive may have been a test: was theater in Arabic eloquent enough to be included among the arts of the khedivate?

In October 1871, Sanua’s troupe again performed short comedies/operettas in Arabic, this time in the al-Azbakiyya Garden.125 Meanwhile, Verdi’s Aida, the main cultural project of Ismail and Draneht, premiered on December 24, 1871, in the Opera House. Parallel to the Italian product for the khedivate, by January 1872 the Arabic theater in al-Azbakiyya had become popular among Egyptians,126 but then ceased for some time. This theater was a potential space for new communal experiences, and it later indeed became a center of learned patriots.

First, it seemed that the khedivate finally would have an Arabic stage. Ismail entrusted the arrangements for an Arabic theater to Sanua, who planned to reopen it on April 10, 1872, in the al-Azbakiyya Garden.127 By April, the Arabic theater (al-malhā al-ʿarabī) was indeed popular among the “modern and idle people,” first with dancing girls from Beirut, then without them. The troupe prepared to perform in the Comédie on April 22, which was the first occasion of an Arabic performance in a khedivial theater.128 The Azbakiyya Garden was crowded that month as a result of rumors that tickets would soon be introduced, replacing the system of free entrance.129 In May, the advertisement of an Arabic drama, known as Laylā, by the Azhari student Muḥammad ʿAbd al-Fattāḥ al-Miṣrī, mentioned “the Arabic theater [troupe]” (al-tiyātrū al-ʿarabī) “now performing in the garden of al-Azbakiyya.”130 In the preface of this drama, the author thanks his friend, “the esteemed director James,” for his advice. He also hails James as a pioneer and dedicates the play to Ismāʿīl Ṣiddīq (“al-Mufattish”), at that time minister of finance.131 ʿAbd al-Fattāḥ al-Miṣrī considered Sanua and Ismāʿīl Ṣiddīq as his patrons or at least as supporters of Arabic theater.

The troupe performed Laylā at least twice in June or July 1872. The first performance was probably part of the garden’s inauguration.132 Le Nil reported that in the theater of “M. James” the audience thought that the actors had actually killed each other during the performance and, when reassured to the contrary, demanded an encore.133 This is the last contemporary report available on the theater of Sanua.

Draneht, Unsī, and the Question of Language

How did Draneht, the master of early khedivial culture, react to Sanua’s Arabic troupe? More important, how did Muḥammad Unsī react, who demanded Arabic plays earlier? Draneht had already made some efforts to publicize opera in Arabic. In the summer of 1869, he hed opera libretti translated into Arabic to “instruct the audience.”134 The prices of the boxes in the Opera House were communicated in Arabic in the journal Wādī al-Nīl, together with a report about the first show.135 But the program of the Opera House in the first season, unlike the Circus of Rancy, was not advertised in Arabic. Only in February 1870 was the opera Semiramis announced in Wādī al-Nīl, together with a definition of the genre of opera, and Muḥammad Unsī’s call for Arabic performances.136 Draneht likely disapproved of the staged amateur, local, and satirical comedies.137 He preferred and always opted for “dignified” or professional Italian or French musical theater. But because Draneht spent the summer of 1871 in Italy (mostly in Milan) and France, dealing with the arrangements for Aida,138 he had no direct control over what happened in Cairo. It was in this context that Sanua’s troupe made its debut and performed in front of the khedive himself in July 1871. Sanua’s later recollections testify that Draneht, upon his return, was not supportive of Sanua’s project.139

Neither was Muḥammad Unsī, for his part, happy with the first Arabic troupe in Egypt. He had initially supported Sanua’s troupe,140 but it seems that he soon changed his mind. Together with the French teacher Louis Farrugia (d. 1886), who worked at the École des Arts et Métiers,141 Unsī proposed a rival Arabic theater enterprise to the government. They submitted their project in April 1872, when the popularity of Sanua’s theater was at its zenith and seemed to be institutionalized by Ismail Pasha. They argued that “the experiment” had not reached a “good result.”142 Their own project, written in French and proposed quite clearly to counter Sanua’s project, was personally recommended to the khedive by Draneht several times, and through the intermediary of Khayri, the khedive’s secretary.143 But why did Draneht support the idea of an Arabic theater project at all?

The imagined Arabic theater of Unsī and its school [!] were planned as a part of Draneht’s administration. Unsī proposed a troupe called the Théâtre National in which young Egyptian boys and girls would be trained to become professional singers and actors. It would use the “Kiosque” of the Garden Theater in al-Azbakiyya, and sometimes the Comédie. The troupe would perform in fuṣḥā and would draw upon the great medieval pool of Arabic texts. Unsī suggested in French that “the Arabic language is amazingly applicable in the art of drama and in the intellectual amusements.”144

Importantly, Unsī’s competition with Sanua does not seem to have been motivated by envy. Rather, Unsī was deeply concerned about the style of official patriotic entertainment. We have seen that his printing press published adab works, journals, and language manuals. The way Sanua realized Arabic theater, mostly in ʿāmmiyya (by April 1872 Laylā was not yet staged), was likely not viewed by Unsī as contributing to the progress of Egypt. In the following years Unsī composed at least four books on Arabic language in his capacity as a language teacher. The first was a language book of Arabic for foreigners, the second a new method in reading Arabic for elementary schools, the next taught fuṣḥā for beginners, and finally he published a new Arabic grammar for elementary schools in three volumes. These works were all printed by his press, perhaps at the order of ʿAlī Mubārak, for the new khedivial schools.145 It was this educational attitude and engagement with the learned Arabic language, coupled with a respect for adab, that informed Unsī’s theater project. We see here the intellectual’s desire to shape modern culture according to his own tastes, representing possibly the whole educational spirit at the time. Unsī’s proposal was backed by Draneht because doing so offered the latter a way to control theater in Arabic, in addition to the European troupes. However, no reply to the proposal survives from the khedive or the government. Instead of Unsī or Sanua, intellectuals from Ottoman Syria took advantage of the momentum to create Arabic theater for the khedivate in the 1870s.

The Repertoire of Sanua’s Theater and Patriotism

Before concluding, since Sanua’s theater was the first enterprise to create a communal experience in the modern Arabic theater in Egypt, it is worth mentioning the images of the patriotic community presented in the performed works. Did these plays conform to the dominant technique of musical theater, that is, history and historicization? Were they comparable to Aida, and could they compete with it?

ʿAbd al-Fattāḥ’s Laylā is a historicized Arab love story resulting in a blood bath between proud tribal Arab leaders in the desert. The trope was based on ancient Arabic epics. The tragedy, with its educated language (though some vernacular words, such as ashūf, are interspersed), including a quotation from the ancient poet ʿAntara b. Shaddād, evoking a moral concept of Arabness. For instance, the father Amīr Zaydān warns the hero Ḥasan not to employ any trick against his rival because “treason is not an Arab or heroic quality” (al-khiyāna laysa hiya min shaʾn al-ʿarab wa-l-fursān).146 When the rival lover, Amīr ʿImrān, plays false, Amīr Zaydān accuses him of not being an Arab because “Arabs do not act in this way, tell me, did you go mad?”147 The drama contained the same intellectual principles that were expressed in Unsī’s proposal: the use of fuṣḥā and tribute to the great Arab literary heritage. The early Egyptian formulation of moral Arabism in this tragedy fit in with the ideal form of a national drama, and indeed it was written, as ʿAbd al-Fattāḥ remarked, “for the sons of the homeland” (abnāʾ al-waṭan).148 Another indication of this intention was Laylā’s immediate publication (in contrast to Sanua’s plays in vernacular Arabic, which remained in manuscript form). ʿAbd al-Fattāḥ’s tragedy represented an early patriotic Egyptian Arabic play.

There was no historical core similarly grounding Sanua’s works, which were written in colloquial Arabic (mixed with French, Italian, Greek, and fuṣḥā Arabic). These can be reconstructed as approximately twelve texts with songs; seven of them were printed posthumously.149 The humor of the plays relies on language mistakes and mutual misunderstandings. There are no heroes, no battles, no myths. A short dialogue ridicules an English tourist. Six comedies are about love and marriage. The main characters are urban Syrians and Egyptians, members of modestly wealthy Arabic-speaking merchant families, interacting with Frenchmen, Greeks, and Englishmen. The play al-Ḍarratayn is an exception; its male protagonist is a hashish addict, and its theme is polygamy. In general, however, the Egyptian characters do not mention subversive ideas; this is especially true of the servants (there are also two European maids), who are portrayed neutrally.150 In contrast, the comedy al-Ṣadāqa praises the government for encouraging foreign investment.151 An Egyptian character in al-Amīra al-Iskandarāniyya asserts that he would give up his status as a French protégé to become a subject of the khedive again. Another character admires the fact that “the governor of Egypt transformed his kingdom’s capital into a garden.”152 These texts, contrary to Moreh and Sadgrove’s interpretation, are not concerned only with “themes far from politics.”153 They ridicule ignorance while praising the khedive. This is why their staging had the potential for irony—even if unintentional irony. In 1872, the lines “The governor of Egypt transformed his kingdom’s capital into a garden” could be made into a barbed joke with the right body language and intonation.

Most important, Sanua did not understand, or could not use, historicization, the principal vehicle of patriotic imagination. Nor did he recognize the fuṣḥā modernity in the works of Abū al-Suʿūd, Unsī, and others. But the Azhari student ʿAbd al-Fattāḥ did use a historicized plot in fuṣḥā Arabic in Laylā. Had the theater troupe survived longer, it might have performed more plays using historical or historicized themes. The troupe had the potential to become a forum for other playwrights in Arabic and thus a vehicle of patriotism. But Sanua misread the horizon of possibilities, looking for fame and money from Ismail, without securing the cooperation with Abū al-Suʿūd, Unsī, and ʿAlī Mubārak, or even the aggressive Europeanizer Paul Draneht. The form of discursive nation-ness that the Muslim intellectuals created was contradictory to Sanua’s vernacular imagination as expressed in his plays.

The idea of a nation without history was unacceptable in early khedivial culture, and realism coupled with irony was not welcomed. In a way, Sanua not only faced the khedive but also the intellectuals who were busy with making fuṣḥā Arabic the language of the khedivate. Ismail did not grant financial help, and the troupe dissolved in the summer of 1872. Sanua tried twice to return to the stage: in 1873 and next in 1876 with a comedy in Italian. In 1877, the inauguration of Théâtre Ismail was advertised with his participation (with the “Egyptian Molière”). The audience did not receive his comeback well.154 At this point the disappointed Sanua joined the circles of the political thinker, Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī. Their activity and the next group of theater-makers are the subjects of the next chapter.

CONCLUSION: THE INVENTION OF MUSLIM MEMORY AND THE LACK OF CAPITAL

The gentle revolution was an attempt to make patriotism the official ideology of the khedivate. This involved the formulation of a language and a historical imagination based on selected cultural motives. This new Muslim memory had to compete with and conform the European aesthetics of Ismail and the actual Ottoman belonging of Egypt. Spatial transformation brought politics to be performed in front of the powerful. Thus the language as a public representation had to be adjusted.

In this period, the Ottoman attachment of Egypt recedes in the background and the Nile Valley is clearly the content of the idea of waṭan. Abū al-Suʿūd, for instance, writes in a well-commented translation in 1872 that he wants to “substitute the details of the French Kingdom’s description, which is the author’s beloved homeland, with the details of Egypt’s geography, God willing, since she is our beloved homeland” (waṭanunā al-ʿazīz).155 This switch of national homelands clearly indicates the territorial meaning of waṭan.

Note that the adjective of “homeland” in Arabic is often ʿazīz which is exactly the title given to Ismail in official Arabic texts, and what he demanded from the sultan in vain. The khedive was discursively identified with the land of Egypt. Fuṣḥā Arabic transplanted the physical body of the pasha into a patriotic symbol by identifying personhood and geography.

The learned language, and the new textual pool associated with it, helped the appearance of Arabness as a moral and communal category. The failure of vernacular modernity as an accepted official representation (though it would eventually be the main language of the entertainment market)156 was partly due to the un-historicity of the vernacular language(s). The religious status, the historical corpus, and the reinvented tradition made fuṣḥā Arabic the perfect candidate for a common ground between khedive, Muslim intellectuals, European Orientalists, and as we shall see soon, Arabic-speaking Christians, with which no version of vernacular Arabic could compete.

The common feature of Unsī’s and Sanua’s enterprises is the lack of capital. Ismail spent hundreds of thousand francs for Italian opera, but gave very limited support to patriotic education and press. The manipulation of absolutist rule by patriotic means in Arabic was thus limited by the absence of funding. Why did Abū al-Suʿūd, Unsī, and even Sanua not apply for private support from Egyptian merchants and aʿyān is a complicated question and needs further research. What did the aʿyān do in this period when they were, in fact, involved in administration through the Consultative Chamber?

Around 1873, it thus became obvious that the khedivate as a regime type is no more than the allocation of some possibilities for aʿyān capitalism through the Consultative Chamber. Ismail started to appoint again more zevat in administrative positions. ʿAlī Mubārak was reduced to being a simple supervisor in 1872. In the coming years, the Ottoman Empire forcefully returned as another homeland in Egypt as we shall see in the next chapter.

1 Muḥammad Unsī, “Malʿab al-Ūbira bi-Miṣr al-Qāhira,” Wādī al-Nīl, 28 Dhū al-Qaʿda 1286 (28 February 1870, 1869 is wrongly printed on the cover page), 1332. Both Sadgrove and Ayalon translate the word ahliyya in the subtitle of the journal Wādī al-Nīl as “popular” to English. Sadgrove, “The Development,” 74; and Ayalon, The Arabic Press, 41. I have translated ahliyya as “local” but in the second sentence as “patriotic,” as a synonym to waṭaniyya. I base this on the use of ahliyya and waṭaniyya as synonyms by ʿAbd Allāh Fikrī in a contemporary letter celebrating the establishment of the journal Wādī al-Nīl as al-ṣaḥīfa al-ahliyya al-waṭaniyya. Fikrī, ed., Al-Āthār al-Fikriyya, 261.

2 Juan Cole characterized the period 1852–1882 as “the long revolution.” I suggest that time was even more accelerated. Cole, Colonialism and Revolution, 110–111.

3 Anderson, Imagined Communities, 85.

4 Letter dated 8 Dhū al-Ḥijja 1284 (1 April 1868), from Ismāʿīl Ṣiddīq to Maʿiyya, 43/227, MST, Microfilm 202, DWQ.

5 Letter dated 21 Shawwāl 1286 (24 January 1870) from Shāhīn Kanj, Nazir-i Cihadiye, 411/46, MST, Microfilm 204, DWQ; Sāmī, Taqwīm al-Nīl, part 3, vol. 2: 849.

6 Goldziher, “Jelentés,” 9.

7 Hassoun, “Les Juifs,” 58.

8 Dykstra, “A Bibliographical Study,” 243–261.

9 Heyworth-Dunne, An Introduction, 362–370.

10 Heyworth-Dunne, An Introduction, 346–347.

11 On Hanafization see Hatina, ʿUlamaʾ, Politics, and the Public Sphere, 36–38; Cuno, Modernizing Marriage, 123–125.

12 Hatina, ʿUlamaʾ, Politics, and the Public Sphere, 32–36.

13 Cf. letter dated 5 Dhū al-Hijja 1286 (8 March 1870), from ʿAlī Mubārak, Nāẓir al-Awqāf, 468/46, Microfilm 204, MST, DWQ.

14 Programme de l’enseigemment, 11.

15 Heyworth-Dunne, An Introduction, 376.

16 Rawḍat al-Madāris, “Iʿlān,” 15 Ṣafar 1288, 3.

17 Heyworth-Dunne, An Introduction, 376–377.

18 Fahmy, Ordinary Egyptians, 32–33.

19 Fikrī, Rasāʾil al-Inshāʾ, Manuscript, 5115 Adab.

20 Fikrī, ed., Al-Āthār, 4–5.

21 Shafīq, Mudhakkirātī, 1:8.

22 Letter dated 31 Ramadan 1288 (14 December 1871), from ʿAlī Mubārak, Mudīr Dīwan al-Madāris to al-Maʿiyya, 447/48, MST, Microfilm 205, DWQ.

23 For instance, the issue of Ghāyat Shaʿbān 1288 (14 November 1871) contains only speeches.

24 “Ṣūrat al-Khuṭba allatī Iftataḥa bi-hā Imtiḥān Maktab al-Marḥūma Wālidat al-Marḥūm ʿAbbās Bāshā,” Rawḍat al-Madāris al-Miṣriyya, Ghāyat Shaʿbān 1294 (9 September 1877), 8–9.

25 Şiviloğlu, “The Emergence of Public Opinion.”

26 Letter dated 15 Jumādā al-Ukhrā 1283 (25 October 1866), from Ismail Ragib to Khedive, 374/39, and letter dated 23 Rajab 1283 (1 December 1866), from Khārijiyya to Khedive, 63/40, both in MST, Microfilm 199, DWQ.

27 Sadgrove, “The European Press,” 114–117.

28 Schwartz, “Meaningful Mediums.”

29 Undated, unsigned note Projet de création d’une Imprimerie Nationale Egyptienne présenté à son Excellence Chérif Pacha Président du Conseil des Ministres; and undated, unsigned [Contract] Entre le Gouvernement Egyptien d’une part et Antoine Mourès, Imprimeur, domicilié à Alexandrie, d’autre part. These are next to a letter dated 11 August 1866, and therefore I believe this is the right year; 5013–002616, DWQ.

30 Cole, Colonialism and Revolution, ch. 4. Fahmy, Ordinary Egyptians, 7–8.

31 Ayalon, The Arabic Press, 19.

32 The only governmental periodical was al-Waqāʾiʿ al-Miṣriyya, which was intermittently published, and in Ottoman Turkish as well. This journal published dynastic praise in addition to official and some local news regularly since the 1830s. Next was a scientific circular for doctors in Arabic, Yaʿsūb al-Ṭibb, which was printed in the governmental Būlāq press from 1865, and a military periodical, but the distribution of these journals was not public.

33 Barak, On Time, 130.

34 Stephan, Das heutige, 174, 325.

35 Sabry, Le Genèse, 113; Ayalon, The Arabic Press, 41.

36 ʿAbduh, Taṭawwur, 60–61.

37 Sadgrove, “The Development,” 73.

38 Cole, Colonialism and Revolution, 127.

39 Barak, On Time, 117.

40 Fikrī, ed., al-Āthār al-Fikriyya, 261–263.

41 Al-Waqāʾiʿ al-Miṣriyya, 18 and 25 July 1867.

42 Ayalon, “Sihafa,” 269.

43 Sadgrove, “The Development,” 74.

44 The final colophon says that the press is owned by Abū al-Suʿūd in al-Harawī, Al-Talwīḥ (1285 [1868]).

45 Vassalli, D’una rappresentazione di Sirene. Muḥammad Unsī’s brother is known from a hand-written note at the end of the manuscript “Tarjamat al-Fāḍil ʿAbd Allāh Abī al-Suʿūd Afandī,” manuscript, Tārīkh Taymūr 1098.

46 Like Dardīr, Ḥāshiyat; Al-Nasafī, Kitāb Kanz al-Daqāʾiq.

47 For instance, Wādī al-Nīl, 25 Dhū al-Ḥijja 1287, 7–8. It also advertised other publishers, such as the government’s Būlāq press, or the publications of Ibrāhīm al-Muwayliḥī.

48 Physically, the press was moved between Bāb al-Shaʿriyya neighborhood in Cairo where Abū al-Suʿūd lived and Kawm al-Shaykh Salāma neighborhood in al-Mūskī.

49 Barak, On Time, 118–119.

50 Schwartz, “Meaningful Mediums,” 425–428.

51 [Mariette,] Furjat al-mutafarrij.

52 Letter dated 31 January 1872, from Draneht to Khayri Pasha, in Abdoun, Genesi dell’ “Aida,” 109–110.

53 [Ghislanzoni], Tarjamat al-Ūpīra [!] al-Musammā bi-Ism ʿĀyida.

54 Schwartz, “Meaningful Mediums,” 304, n. 184.

55 The printing press of the journal changes to Maṭbaʿat al-Madāris al-Milkiyya bi-Darb al-Jamāmīz in Cairo; starting at vol. 2., n. 4 (Ghāyat Ṣafar 1288 = 22 May 1871).

56 Sadgrove, “The Development,” 93.

57 De-Marchi, La fiesta dei Khalidj in Cairo printed by “Imprimerie Onsy et Mourés au Mouski” in 1869. It is unclear whether the “Imprimerie Onsy et Mourés” and the earlier “Imprimerie franco-arabe Onsy frères” were identical with Maṭbaʿat Wādī al-Nīl.

58 Letter dated 19 September 1868, from Charles François Antoine De Morely to the Khedive, 192/44, MST, Microfilm 203, DWQ.

59 Wādī al-Nīl, 3 Rabīʿa 1287, 2–4.

60 However, the first translation of Offenbach’s La belle Hélène (Hīlāna al-Jamīla) was printed at the Būlāq press. Perhaps because it was not Abū al-Suʿūd’s translation.

61 More on the private printers in Schwartz, “Meaningful Mediums.”

62 In the colophon of Mubārak, Kitāb Nukhbat, the owners are two brothers Muḥammad Rifʿat and Maḥmūd Fāḍil. It is possible that the press was taken over by them after the death of Abū al-Suʿūd in 1878. Ibn Nujaym’s Kitāb al-Ashbāh wa-l-Naẓāʾir was printed at Maṭbaʿat Wādī al-Nīl at the end of Ramaḍān, 1298 (August 1881); and Ibn Miskawayh’s Tahdhīb al-Akhlāq at the end of Shawwāl 1299 (August 1882); its multazim (contractor) was a rival printer, Aṣlān Bey Kāstilī (Castelli), which may indicate that the press was no more profitable. For the Castellis see Schwartz, “Meaningful Mediums,” 293–325. There is a later Wādī al-Nīl press and journal in the early twentieth century that should not be confused with this one.

63 Two volumes between April 1869 and March 1871 (corresponding to 1286 and 1287 hijrī years). However, Sadgrove had access to the first issue in 1867.

64 Cf. the announcement in Wādī al-Nīl, 25 Dhū al-Ḥijja 1287, 2.

65 Barak, “Outdating,” 23.

66 Al-Ibshīhī, Al-Mustaṭraf, 1.

67 Wādī al-Nīl, 3 Rabīʿ al-Awwal, 1287, 5–6.

68 “Tarjamat al-Fāḍil ʿAbd Allāh Abī al-Suʿūd Afandī,” manuscript, Tārīkh Taymūr 1098, Microfilm 12979, Dār al-Kutub al-Miṣriyya. Al-Rāfiʿī, ʿAṣr Ismāʿīl, 1: 250.

69 Sadgrove, “The Development,” 76.

70 “Tarjamat al-Fāḍil ʿAbd Allāh Abī al-Suʿūd Afandī,” manuscript, Tārīkh Taymūr 1098, Microfilm 12979, Dār al-Kutub al-Miṣriyya.

71 Cole, Colonialism and Revolution, 127.

72 ʿAbduh, al-Taṭawwur, 66.

73 Sabry quoted in Heyworth-Dunne, An Introduction, 345.

74 However, the early 1880s publications of al-Maṭbaʿa al-ʿIlāmiyya use very similar fonts to the Wādī al-Nīl fonts.

75 It was related to that journal in several ways. It was printed on its press in the first year, it was supervised by al-Ṭahṭāwī until 1873, who was Abū al-Suʿūd’s teacher, and Abū al-Suʿūd himself published articles in this journal.

76 Letter dated 5 Dhū al-Ḥijja 1286 (8 March 1870), from ʿAlī Mubārak (Nāẓir al-Awqāf), 468/46, MST, Microfilm 204, DWQ.

77 ʿAlī Bāshā Mubārak, “[untitled letter],” Rawḍat al-Madāris al-Miṣriyya, 15 Muḥarram 1287 (16 April 1870), 7–10.

78 Ḥasan and Dusūqī, Rawḍat al-Madāris.

79 Yousef, “Reassessing Egypt’s Dual System of Education.”

80 Aḥmad Naẓmī, introduction to the greeting poem, Rawḍat al-Madāris al-Miṣriyya, 15 Muḥarram 1287 (16 April 1870), 14.

81 Rawḍat al-Madāris al-Miṣriyya, 15 Ramaḍān 1290 (6 November 1873), 3.

82 Rawḍat al-Madāris al-Miṣriyya, Ghāyat Dhū al-Ḥijja 1290 (19 February 1874), 3–7.

83 Rawḍat al-Madāris al-Miṣriyya, Ghāyat Rabīʿ Awwal 1287 (1 June 1870), 3–6, here 4.

84 Fikrī, ed., Al-Āthār, 262.

85 Sadgrove, “The European Press.”

86 Although there are a number of studies of Egyptian historiography, these early years are typically left out. For instance, Di Capua, Gatekeepers.

87 Abū al-Suʿūd, Kitāb al-Dars al-Tāmm.