Constitutionalism and Revolution:

The Arab Opera

How did the uncodified compromise between the khedive and local notables and intellectuals break down? Why couldn’t they agree in basic principles? The period from the mid-1870s to 1882 is an extremely complex one. There was a financial crisis, European takeover of the khedivate’s fiscal politics, social mobilization, and army revolt: the ʿUrābī revolution in 1882.

This chapter, instead of a linear progress to revolution, highlights two traits: the return of Egypt’s Ottoman attachment in public texts and the relationship of intellectuals to power. The ambivalent use of the word waṭan reappeared, denoting both the Ottoman Empire and Egypt. Ismail could still rely on the fragile support of local notables and intellectuals. But after he was deposed in 1879, his son Tevfik was unable to maintain this support. Importantly, all parties attempted to use Ottoman sovereignty for local change.

In this period, large groups of society were alienated, and traditional client-patron relations were broken. The ʿulamāʾ at al-Azhar disagreed over reforms and formed opposing alliances. The khedive and European controllers introduced new taxes, and reduced the number of soldiers in the army (94,000 troops in 1871 to 36,000 in 1879, 18,000 planned for later).1 The too knowledgeable Ismāʿīl Ṣiddīq was arrested and murdered in 1876 possibly by the order of Ismail. New political figures appeared: the anti-British Persian thinker Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī (1838–1897), living on a government pension in Cairo, found useful allies in Ottoman Syrians to fight European imperialism.

The events, and the role of General Aḥmad ʿUrābī, were immediately the subject of ideological readings.2 Scholars look at this period and the revolution as “proto-nationalist,”3 others as a double movement of a “struggle among social classes” and “regional patriotism.”4 Landau suggests considering the role of freemasonry and the conspiracies of Abdülhalim (Ismail’s uncle);5 Berque, Sālim, Schölch, and Cole prove the wide social basis of the movement with differing interpretations;6 EzzelArab refocuses the role of the elite and constitutionalism;7 and recently Khuri-Makdisi and Fahmy channel the cultural production of the period into the history of radicalism, and Egyptian vernacular nationalism, respectively.8

Through the intersection of patriotism and theater this chapter also explores how revolutionary culture informed the forgotten origins of Egyptian stardom. Salāma Ḥijāzī (1852–1917), the first Egyptian singer to sing in the Khedivial Opera House, appears during the turbulent spring of 1882 with the impresario Sulaymān Qardāḥī (1854?–1909). Egyptian stardom origins in a trans-Ottoman Arab enterprise: Ḥijāzī became a national star in the 1880s through his associations with Syrian troupes. We start with the Syrians, the new cultural entrepreneurs of Arab patriotism in Egypt.

KHEDIVIAL SYRIANS

Ottoman Syrian migration to Egypt in the 1870s was a potential source of loyal subjects in the khedivate. In the grand narratives of resistance, some of these individuals are destined to be revolutionaries. In contrast, I look upon their cultural activity as initially loyal to Ismail. Their behavior could change into public criticism because of their independent capital and their protection by rival pashas and European powers.

The Beirut-Cairo Connection

As we have seen in chapter 1, Ottoman Syrians remained aware of the power of the Mehmed Ali family after the 1830s occupation. There had also been small but important Syrian Christian trading communities in Egypt since the eighteenth century.9 Prompted by the changing economy of the Lebanon mountain, and Ottoman efforts of reintegration, Syrians migrated in larger numbers all around the world. Egypt was an attractive location, since no passport was needed for them and the ticket was relatively cheap (at least it was remembered as such in the Syrian diasporas).10

The image of khedivial Egypt in the Syrian Arabic public sphere was certainly attractive. We have discussed Said’s relations with the Beiruti elite, and Ismail further advanced the image of Egypt and his own rule by financing Ḥadīqat al-Akhbār, the most important journal, and the projects of the intellectual Buṭrus al-Bustānī in Ottoman Beirut.11 In Ḥadīqat al-Akhbār, and in al-Bustānī’s journals al-Jinān and al-Janna, Egypt was often described in the most extravagant words. But there was no need for khedivial money: according to al-Najāḥ, yet another Christian Arab journal in Beirut, which had no proven connection to Ismail, the khedivate of Egypt was “the most advanced country in the East” in 1871.12

As part of the growing public sphere in a city of merchants, there was a revival of Arabic theater in late Ottoman Beirut. In a new school for patriotic education, al-Madrasa al-Waṭaniyya, opened by Buṭrus al-Bustānī in 1863, teachers such as Nāṣīf al-Yāzijī encouraged theater activities,13 or wrote plays, such as al-Sayyid Salīm Ramaḍān and Ibrāhīm al-Aḥdab.14 The book Arzat Lubnān, publicizing Mārūn and Niqūlā Naqqāsh’s ideas and plays, was published in 1869, prompted by the Ottoman governor’s request.15 Coincidently, this was the year when the Comédie and the Opera House were constructed in Cairo. As we have seen, in 1871 plays were sent to Cairo from Beirut,16 and al-Jinān asked the khedive to establish Arab theaters.17 Perhaps al-Jinān’s correspondent made another proposition, because the correspondent of the Istanbul paper al-Jawāʾib ridiculed him (and the editor, al-Bustānī) for asking the khedive to “create a theater in which he can bring dancers and dancing girls to perform.”18 There is no known reaction from Beirut to Sanua’s theater troupe in Cairo. And after that amateur troupe dissolved in 1872, the floor was open for the more professional Syrians.

In the 1870s, Ottoman Syrians were already professionally instrumentalizing the past for community building. Luke Leafgren shows that Salīm al-Bustānī, editor of al-Jinān, used the phrase al-umma al-ʿarabiyya (the Arab community or nation) both in 1870 in his journal (which also had ḥubb al-waṭan min al-īmān – “the love of the homeland is part of faith” as its title slogan) and in 1874 in a historical novel about the Muslim conquest.19 In 1875, Al-Jinān also mentioned Arabic plays as helping al-umma al-ʿarabiyya.20 William Granara argues that Jurjī Zaydān’s later novel about Muslim Andalusia (1904) established the literary use of Andalusia as a chronotope in Arabic literature—a compressed past time and space that may be resurrected in the present.21 We shall see that Muslim Andalusia started to develop earlier in the Arab historical-political imagination as a topos in theater, connecting patriotism and dynastic loyalty.

A Patriotic Migration

The migration of the playwright, translator, and impresario Salīm Khalīl Naqqāsh (1850–1884) from Beirut represents a calculated migration pattern. It was a conscious decision that was preceded by contact and the survey of possibilities. Salīm was the nephew of Mārūn and Niqūlā Naqqāsh, the merchants-poets-playwrights. He studied French and Italian, and worked at the Customs in the Beirut port, perhaps as a protégé of his uncle (Niqūlā also worked at the Customs).22 He wrote and printed his Arabic tragedy Mayy or Mayy wa-Ḥūrās using elements from Corneille’s Les trois Horaces et les trois Curiaces in 1868 (perhaps translated earlier in 1866) and enriched it with songs.23 It is not known whether Salīm was involved in the performances of the 1860s.24 In 1874, he reprinted his Mayy with an introduction in which he praised Khedive Ismail and with a special dedication to a merchant in Alexandria. As a next step, in early 1875 Salīm Naqqāsh traveled to Egypt to look for better prospects.

The young man was charmed by khedivial Cairo, which seemed to him much more advanced than Beirut. In addition, he hoped to find financial patronage. He later explained to his Beiruti audience that “our city’s material means became too few for what I needed [for my theater], so I decided to realize my aims somewhere else . . . I saw that people enter [Egypt] as if it were the Paradise,” remarking also that Ismail had financed Salīm al-Bustānī.25 Likely through al-Jinān’s new local correspondent, Edward Ilyās,26 Salīm Naqqāsh contacted the superintendent Draneht, and watched a performance of Aida at the Opera House in the early spring of 1875. He discussed theater with Draneht, who was “satisfied with his [Naqqāsh’s] competence.” Sadgrove states that Naqqāsh persuaded Ismail Pasha “through the offices of Draneht” to support Arabic theater,27 which possibly included the establishment of two specifically designed buildings for Arab troupes, one in Cairo and one in Mansura.28 It is unclear who persuaded whom: the superintendent who recognized the value of a professional, and loyal, Arab Thespian in the service of the khedivate or the young Beiruti intellectual who needed financial support from a government. Be that as it may, Naqqāsh and Draneht exchanged ideas, which resulted in the khedive’s issuing an decree (irāda) that Naqqāsh should prepare Arabic plays for late-Ottoman Egypt.29 Naqqāsh framed this as a means that would help him to advance the social body and al-umma al-ʿarabiyya (the Arab nation).30

Preparations: The Arabic Aida and Isḥāq

Now there was a chance to include Arabic theater in khedivial culture. Salīm Naqqāsh undoubtedly prepared for an Arabic theater as part of the khedivial system or at least did everything possible to become acceptable. Unlike James Sanua in 1871–1872, this young man understood the requirements of the regime. Upon his return to Beirut, he immediately translated “parts of” the opera Aida into Arabic. It was the second translation of the libretto, the first having been undertaken by Abū al-Suʿūd in 1871. He dedicated the text again to Khedive Ismail and published it before July 1875 in Beirut.31

Naqqāsh’s ʿĀʾida is in five parts but the original Aida has only four acts. When later this Arabic Aida was performed, the original music and singing were also changed to “Eastern melodies.”32 The earlier translation of Abū al-Suʿūd was not for public distribution or performance. By retranslating Aida, the main work of early khedivial culture, into ʿĀʾida to be performed, and printing it for sale as a booklet, Naqqāsh fulfilled an important service to spread khedivial taste and its preferred historical imagery in Arabic.

His second activity was the training of a company with another theater-loving customs officer, the even younger Adīb Isḥāq (1856–1884). Isḥāq, born in Damascus, was a Greek Catholic Wunderkind of the Beiruti literary circles. By 1874, he had written poetry and a play, The Chinese Incident, which was staged in Beirut. In 1875, when he was only nineteen, he translated Racine’s Andromaque into Arabic, possibly as a preparation for serving the khedive. In accordance with the musical theater tradition, the young playwright recommended the use of several Turkish tunes in the performance of this play.33 He also translated Offenbach’s La Belle Hélène into Arabic, possibly in this year,34 which was the favorite operetta of Ismail. Naqqāsh and Isḥāq assembled seventeen actors and actresses and put on rehearsals in Beirut. They rehearsed al-Bakhīl and the Arabic Aida. We should not forget that such training was impossible in Cairo for Muḥammad Unsī or even for James Sanua four years earlier. Although the Beiruti troupe was ready by August 1875,35 an outbreak of cholera postponed their arrival for more than a year.

“Actors of the Khedivial Plays:” Music, Fuṣḥā, Nation-Ness

The 1875 summer and autumn articles in al-Jinān suggest that Naqqāsh’s goal was to serve Arabic plays for Khedive Ismail and Draneht Bey. The khedivate was a favorable regime for Ottoman Arabism. At this moment, Beiruti merchant culture was ready to join the production of patriotism in khedivial Egypt. The construction of an Arab cultural patriotism in which the khedive figured as a benevolent ruler also became the work of Syrians. The previous preference for fuṣḥā among Egyptian intellectuals gained an additional importance for the Christian Syrians since it was a means that subjected everyone equally regardless of religion or origin. Naqqāsh noted that the Egyptian and Syrian vernaculars are different and he decided to “perform Arabized plays in pure Arabic” (ʿarabiyya ṣaḥīḥa).36

The Naqqāsh-Isḥāq troupe reached Alexandria only in November 1876. This delay was critical because meanwhile, in response to Khedive Ismail’s suspending the payment of the enormous interest on foreign debt, his creditors, backed by the French and British governments, forced the ruler to accept a Debt Commission to control the finances of the province. The commission cut the expenditure of the government, and by 1878 had compelled the members of the khedivial family to transfer most of their estates to the government.37

The agreement between Draneht and Naqqāsh and the khedive’s order was known in Egypt. Rawḍat al-Madāris republished an article of al-Jinān about the history and modernity of Alexandria, in which the anonymous author speculated that the Syrian actors might first reach an understanding with the European actors in Alexandria, with whom they would share the same theater (perhaps the Zizinia). In the article the troupe is called “the actors of the khedivial plays” (mushakhkhiṣū al-riwāyāt al-khidīwiyya).38 Was this a hint that the Syrian troupe was intended to be an official, khedivial enterprise?

The would-be khedivial actors arrived in an Alexandria where the Syrian community was already large. They had help. Syrian journalist-capitalists, the Taqlā-brothers had just established their journal, al-Ahrām in the summer of 1876; there were Christian schools; and soon a number of Syrian Christian charity societies. The troupe of Naqqāsh also received help from Ömer Lutfi Pasha (the governor of Alexandria, perhaps the same man who had supported Sanua four years before), possibly from the khedive, and press support from al-Ahrām, the bookshop-owner Ḥabīb Gharzūzī, and the press-owner and journalist Salīm Ḥamawī. Upon their arrival, Al-Ahrām immediately praised the Naqqāsh troupe in an article. The paper reminded the public that theater was “one of the primary means to fuse society together” and that “all civilized countries give this matter the utmost consideration” therefore attendance at the performances was an obligation.39 In a later article, Isḥāq remembered that, like Jalāl and Mubārak earlier, they were indeed convinced that “theatre [was] one of the reasons for the progress of human society.”40

As we have seen, popular mimetic entertainment in Egypt was a vernacular one, and Sanua also tried a vernacular theater. In contrast, the Syrian plays were written mostly in fuṣḥā Arabic and were mostly historical or historicized (the staging, however, must have contained some vernacular). This made nation-ness the matter of an educated imagination. The Syrians employed local music to facilitate their acceptance. Mārūn Naqqāsh at the end of the 1840s had already chosen opera as the format of his first play, because he thought that musical theater would entertain “his people.”41 Salīm Naqqāsh and Adīb Isḥāq, twenty-eight years later, used music as a means to make the Beiruti troupe acceptable to the Egyptian audience. Naqqāsh deliberately favored “Arabic songs” (anghām ʿarabiyya) as opposed to “European” (afranj) ones in the plays. He argued that there is difference in taste.42 There was an additional reason. A Syrian in Alexandria, Buṭrus Shalfūn, taught Egyptian tunes to the members of the troupe, so that Egyptian music might sweeten the fuṣḥā of the plays and make the audience forgive their shāmī colloquial.43 We shall see that soon Egyptian singers would be involved in Syrian troupes establishing a pattern that would define Arab entertainment history up to the present. These developments, especially music, were important conditions in the communal experience of aural patriotism.

The Naqqāsh-Isḥāq troupe performed in Alexandria from late December 1876 until February 1877, for less than three months. They staged translated or Arabized French and Greek dramas (Mayy, al-Kadhūb, Andrūmāq, Sharlumān, perhaps Fidrāʾ), original Arabic plays (Mārūn Naqqāsh’s Hārūn al-Rashīd, al-Salīṭ al-Ḥasūd, Salīm Naqqāsh’ al-Ẓalūm) but possibly not ʿĀyida.44 These plays in fuṣḥā Arabic embodied either a translated version of European myths or an Arab historical imagination, or in fact, a mixture of both. This repertoire suggests a very different idea about patriotic Arabic culture from that of James Sanua’s vernacular comedies. The plays would likely have been approved by Muḥammad Unsī and ʿAbd Allāh Abū al-Suʿūd, had they ever seen the performances. The plots were on historical or historicized topics, conforming to educated patriotic conditions, and the use of fuṣḥā made them fit for presentation in front of the khedive.45

In order to fulfill the agreement, Salīm Naqqāsh traveled to Cairo in the summer of 1877, with the aim of finally arranging evenings for his troupe in one of the khedivial theaters. By that time, Isḥāq had already left Alexandria and the troupe, and set up a press in Cairo, which published a journal, Miṣr (Egypt), from July 1877. He immediately supported Naqqāsh in an article in Miṣr in his aim to perform within the frames of khedivial culture. Isḥāq wrote that “it has been the intention of [Naqqāsh] Efendi to let this [troupe] perform in Cairo in the service of the noble khedive.”46

However, no performance was arranged. From 1877 Draneht was mostly in Italy; Ismail seemingly lost interest in financing a loyal Arabic troupe. Even Rawḍat al-Madāris ceased to be published in 1877. Naqqāsh then left the troupe in Alexandria and joined his friend at the journal Miṣr; he then published the periodicals al-Maḥrūsa (1877), al-Tijāra (1878), and al-ʿAṣr al-Jadīd (1880). This was good business since soon Naqqāsh could afford a house worth of French Fr 16,000 in Alexandria.47 The young men (Isḥāq was only twenty-one in 1877) became vocal in criticizing foreign intervention through their periodicals, expressing a strong Ottomanism.48 While it might be striking that in his first visit in early 1875 Naqqāsh was blind to the autocratic nature of Ismail’s rule, it is equally striking how quickly he and Isḥāq switched from loyal theater to critical journalism. This was due to their meeting with Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī.

AN EMERGING ACTION FIELD: OTTOMAN CONSTITUTIONALISM IN EGYPT

We leave briefly the construction of patriotism in order to survey ideas deriving from Egypt’s Ottoman context. Excellent studies discuss the activity of the thinker al-Afghānī and his followers in khedivial Egypt: Landau and Kudsi-Zadeh stressed the role of the secret societies in political activity,49 and Cole added new sources about “the ideology of dissent” at the time.50 Here I further contextualize al-Afghānī within the Ottoman universe of the late 1870s. This context was defined by the Ottoman constitution, the Russian-Ottoman war, the 1878 Congress of Berlin, and the still-ongoing competition within the ruling zevat family of Egypt.

In my interpretation, efforts were directed at the repair of the khedivial system, not at its demise. However, there was no agreement on the diagnosis of the roots of crisis and on a coordinated solution. Hence the emergent social actions, although aimed at stabilization, unintentionally challenged the incumbents of power. Almost all “challengers have sold themselves on some collective identity to justify their position as challengers,”51 and this collective identity was mostly patriotism at the time. The clash, or failed synchronization, between interests and ideas of the main actors, however, is the subject of this subsection as much as it was related to our main topic: the Ottoman context and the relationship of intellectuals to power. Let us see the central figure in the master narratives of revolution—as an Ottomanist.

Al-Afghānī as an Ottomanist

Jamāl al-Dīn, a Shīʿī Muslim and a sayyid (descendent of the Prophet), widely traveled between Persia, Afghanistan, India, and Istanbul in the period 1857–1869. British imperialism had a thorough impact on his political views. He advised an Afghan emir against the British in 1867–1868 and may have developed relations with Russia.52 Then he arrived in Istanbul in 1869. Due to his networking skills, and magnetic personality, concealing his Shīʿī origins (calling himself “al-Afghānī,” though later in Egypt he signed his letters as Jamāl al-Dīn al-Ḥusaynī53), in February 1870 this unknown sheikh could give a speech at the opening ceremony of the first Ottoman university (Darülfünun), in which he urged the Islamic milla to be open to Western science.54 A later talk of his was, however, used by the Ottoman ʿulamāʾ to crack down on the new educational institution.55 This traveling figure of Western Asia resonates with the image of a wandering Sufi challenging the established men of religion.

The context of al-Afghānī in the 1860s was the so-called New Ottoman ideology, and his and his associates’ activity in 1870s Egypt was a late continuation of that Ottomanism. A loose association of intellectuals, statesmen, and Ottoman aristocrats, called New Ottomans (Yeni Osmanlılar), preached Muslim reforms in order to strengthen the Ottoman Empire in the 1860s. At the center was the demand for a constitution, which would help imperial regeneration. The sidelined Mustafa Fazıl, half-brother of Ismail, was their main supporter, and, in fact, staged himself as their representative in 1867–1868.56 After his death in 1875, Abdülhalim, who may have been involved earlier (his 1868 schemes in Egypt, especially Jamʿiyyat al-Maʿārif, resembled their program [see chapter 2]) continued to demand reforms. Al-Afghānī maintained his Istanbul contacts during his stay in Egypt.57

Mustafa Riyaz, the chief treasurer of Ismail at the time, invited the sheikh, who arrived in Cairo sometime in late March 1871.58 They may have already known each other from as early as 1866.59 Riyaz served in various government positions from the 1850s, and had accumulated large estates, but lived modestly. He was a devoted Muslim, of possibly Jewish origins, believing in the importance of Muslim revival, but was also impressed by modern technology. He was a fierce guardian of monarchical hierarchy and wanted just government, like the New Ottomans.60 In 1873–1874 he became Director of Education and maintained the work of ʿAlī Mubārak. Riyaz may have been a secret supporter of Abdülhalim (he was a member of Jamʿiyyat al-Maʿārif in 1868). The ideas of Riyaz and al-Afghānī seem to be in accordance for a long time. They only fell out after the establishment of the Nubar government (August 1878). Riyaz considered the reforms to be beneficial for just administration, even at the price of European ministers and high-salaried employees, while al-Afghānī thought allowing Europeans to control would lead to the colonization of the province.61 In December 1878, Riyaz Pasha was still mentioned as “the friend” of al-Afghānī.62 It is certain that al-Afghānī until this time enjoyed Riyaz’s protection.

The summer of 1877 was an Ottoman moment in Egypt. The Russian-Ottoman war started. After the deposition of Sultans Abdülaziz and Murad, the new sultan Abdülhamid II was forced to declare the constitution in December 1876, and in 1877 elections were held in all provinces, but not in Egypt or in Tunis. Despite poor beginnings, which even involved the beating of his first Egyptian follower Muḥammad ʿAbduh by Azhari students,63 by this moment in 1877 al-Afghānī was able to attract a number of followers: Syrian Christians, Muslim notables, Azhari students, even some Europeans.

This group instrumentalized print technology and capital professionally for bringing Ottomanism back in Egypt. ʿAbduh started to publish articles in the new journal al-Ahrām. The once “khedivial actors” Adīb and Naqqāsh also engaged in journalism in the summer of 1877, expressing Ottomanism. Adīb wrote an article in his journal Miṣr entitled “The King and the Subjects” (Al-Malik wa-l-Raʿiyya) in which he praised constitutional government, both the Ottoman and the khedivial ones! In the atmosphere of the Ottoman-Russian war, he compares the “wise, constitutional” (al-ḥakīma, al-shūrawiyya) Ottoman government to the backward, unconstitutional, Russian autocracy. He also announces that different regime types fit different peoples: for instance, the “republic” (jumhūriyya) is not fit for China and “despotic kingship” (malakiyya istibdādiyya) is not fit for England. In his wording, waṭan (the homeland) means the Ottoman Empire at this time—in Egypt.64 Al-Afghānī may have had the same opinion at the time, and after the Ottoman defeat he started a six-month period of mourning.65

Thinking about reforming Ottoman politics functioned as an umbrella ideology. It is unclear who benefited most in this network of intellectuals: al-Afghānī, a spiritual leader, instrumentalizing the young Muḥammad ʿAbduh and the Syrian actor-journalists in a sect-like atmosphere (Adīb especially uses magnificent Sufi titles for Afghānī [mawlānā]),66 or the young men utilizing al-Afghānī’s connections for permissions to establish journals as business enterprises (in 1878 his patron Mustafa Riyaz Pasha became minister of the interior). All these possibilities may have been true. Keddie and Cole’s suspicion about al-Afghānī preferring philosophical and political over Islamic teachings in these years can be corroborated by the memoirs of his student Ibrāhīm al-Hilbāwī (1858–1940). Al-Hilbāwī remembers that the lectures were “mixed with politics in which he took up those issues that concerned Egypt, India, Afghanistan, and Turkey.”67 This direction made his teaching acceptable for Christians as well as Muslims. The Ottoman Empire was used as a principle of solidarity in Egypt in a moment of war and defeat.

Freemasonry and Societies

How did these progressive Ottomanists in Egypt network? The most important format for socializing was freemasonry, which was an almost public institution. Freemasonry was related to household politics. Ismail, Tevfik, and other zevat were all freemasons for political reasons. Abdülhalim remained in contact with freemasons in Egypt after his exile in 1868 to Istanbul.68 (In 1868, Sanua was also a member of a lodge.) Al-Afghānī himself was in contact with French and Italian lodges from 1875 on, and in December 1877 he was elected to the Star of the East Lodge 1355,69 although from time to time he was invited to other lodges, such as La Concordia.70 The Star of the East was established by a British diplomat and until 1875 was secretly chaired by Abdülhalim from Istanbul.71 Next to Christian Syrians the membership also included Egyptian notables such as ʿAbd al-Salām al-Muwayliḥī, ʿUthmān and Sulaymān Abāẓa, ʿAbd Allāh Fikrī, Buṭrus Ghālī, and some Egyptian army officers. Even the sidelined Muḥammad Unsī, the intellectual demanding Arabic plays in the previous chapter, was a member.72

Freemasonry connected journalism and Ottomanism: the journal Ḥaqīqat al-Akhbār (The Truth of News) was printed in Cairo from April 1877 with freemason symbols on its title page. This was a pro-Ottoman, private periodical, edited by a certain Anīs Khallāṭ, bringing news of the Ottoman-Russian war, including translations of articles from the Istanbul-based Ottoman journals. The fact that Khallāṭ could use telegraphs extensively indicates that significant capital or government connections were involved. In this journal, waṭan clearly meant the empire, and “interior news” meant news from the empire, including Egypt but not only Egypt.

The Egyptian aʿyān and village headmen joined Syrian merchants and were also active as Ottomanists to some extent. In 1878 there was an effort to re-establish fragile ties especially between Lower Egyptian notables and Ismail Pasha through Ottomanism. In January 1878, a patriotic society was funded in Tanta. This city was the center of the 1860s alliances designed by Ismāʿīl Ṣiddīq (assassinated in 1876). In January 1878, al-Ahrām reported that local notables and merchants in Tanta had established a society out of “patriotic fervor and Arab defense” to help the injured Egyptians fighting in the Ottoman army and invited Ismail to a celebration (laylat al-uns) in February. The khedive accepted the invitation, and all members of his entourage, and hundreds of village headmen joined the occasion. Many singers sang, the government military band performed, and the evening ended with fireworks. Ismail distributed Ottoman medals to the local consuls (mostly Syrian Christians) and to many village headmen. Like the 1866 celebrations in the same city, this was organized or encouraged by the government, since Shāhīn Pasha, the mufattish now, oversaw the preparations together with the rich merchant Dimitri Duhhan (the German consul in Tanta) and ʿAbd al-ʿĀl Bey who was the president of the Gharbiyya provincial council and who were all the founding members of the society. The celebration was enacted again as a moment of affective community of vertical togetherness during which the local village headmen paid respect to the khedive. Al-Ahrām invited all “sons of the homeland” to participate in order to help the (Ottoman) army to defend the homeland (that is, the Ottoman Empire).73 Again waṭan in the moment of war becomes a transparent idea, an imagined territory, through which one can see both Egypt and the empire.

Al-Afghānī’s Opinion of the Khedivate

What was al-Afghānī’s opinion about Ismail personally and his khedivate? Cole attributes an unsigned, unpublished essay from 1877 to al-Afghānī in which the author blames the Ottomans for Muslim decline but praises the Egyptian reforms and Ismail’s government.74 In February 1879, he called for the reform of the regime in his first public, enigmatic article entitled “Despotic Government” (al-Ḥukūma al-Istibdādiyya) in the journal Miṣr. This was perhaps influenced by a public letter of Ismail’s rival Abdülhalim in 1878.75 Al-Afghānī elaborates the topic of despotism, which, as we have seen, by that time had been a trope in Arabic thought. In this article al-Afghānī categorized the khedivial regime as an “enlightened despotism” but an “inexperienced one” which leads to ruining the people. Al-Afghānī thought that a professional enlightened despotism—a wise one—was necessary for “the sons of the East.”76 In a police interrogation al-Afghānī maintained that he was a supporter of Ismail and his son Tevfik, as we shall see below.

The “Patriotic Party” and The Fall of Ismail and Afghānī

While the spring of 1879 is characterized as a “spring of discontent” by Cole, strong voices supported, or at least recognized, Ismail Pasha in exchange for representation and protection of rights. In March, a significant group of notables, many of the members of Majlis Shūrā al-Nuwwāb, proposed an alternative fiscal plan and demands for a constitution to the khedive. This has been called “The National Program” (Lāʾiḥa Waṭaniyya) in scholarship.77 The document, emerging from “the politics of notables,” to use Albert Hourani’s concept, was shrewdly shown by Ismail to the European controllers as a sign of support from the “Patriotic Party” (often translated as the “National Party,” al-Ḥizb al-Waṭanī). In this “party,” many notables saw the khedive as a legitimate ruler who should represent their interests. However, under European pressure, Sultan Abdülhamid II deposed Ismail on 26 June 1879.

After the deposition of Ismail, al-Afghānī was also deposed from the presidency of the lodge with the accusation of “despotism [!] and intervening in political issues contradictory to the codes” on 1 July 1879;78 and was soon exiled from Egypt. He also broke up completely with Riyaz Pasha (Riyaz would be also briefly exiled). In a police interrogation before he left, al-Afghānī described a break in his freemasonry lodge over who would be the right successor of Ismail. He said that he preferred Tevfik while the earlier leaders of the lodge, and “some Syrians,” preferred Abdülhalim. While he denounced “some Syrians” during his interrogation, a devoted Syrian follower, Salīm al-Bustānī in fact showed up at the police station, ready to support him.79 Given that Tevfik indeed became the khedive, al-Afghānī’s claim must be handled cautiously. He referred to himself and his followers as from al-Ḥizb al-Waṭanī (The Patriotic Party; possibly in contradistinction to the Abdülhalim supporters).

“Patriotic,” or “National” as it is often translated, in the name of the party must have meant that the members were supporters of the constitutional proposal and regarded Ismail and Tevfik as legitimate rulers. Certainly there are overlaps among Afghānī’s supporters in the lodge and the signatories of the National Program, starting with ʿAbd al-Salām al-Muwayliḥī.80 Despite a much later recollection of Muḥammad ʿAbduh about discussing the assassination of Ismail,81 the evidence above suggests that, compared to European rule, al-Afghānī considered the khedive, and his son, the lesser evils.

Postscriptum to al-Afghānī and Riyaz

No coherent collective action emerged during the coming years after the summer of 1879. The important intellectual institution Al-Azhar was divided. Patriotic ideas among the ʿulamāʾ were connected to the defense of religion.82 In the autumn of 1881, when, shaken by cuts and the French occupation of Tunisia, the army demonstrated, the blind Sheikh Ḥusayn al-Marṣafī underlined the connection between the community—umma, often translated as “nation,” could be unified by language, location, or religion—and the geographical territory of living (waṭan) but this did not make him a patriot in the sense of giving priority to territorial community over Muslimness.83

Others, like the editors of al-Ahrām, cooperated, or were forced to cooperate, with the government, and it is possible that Salīm Naqqāsh also did so. For instance, al-Hilbāwī, the student of al-Afghānī, after the exile of his teacher, published an article in Naqqāsh’s journal al-Tijāra about the misuse of power in the countryside. He was arrested for this, and brought to the Interior Ministry in 1880. There he saw the original manuscript—that he sent by post to the editor—in the hands of the meanwhile reinstalled Riyaz Pasha, prime minister and minister of the Interior.84 Free speech did not necessary bring misery: after a short imprisonment, al-Hilbāwī in fact was given an editorship at the state bulletin al-Waqāʾiʿ al-Miṣriyya, which was headed by Muḥammad ʿAbduh at the time (1880–1881). This was a result of Riyaz’s renewed scheming, through the Egyptian pupils of al-Afghānī. He is also said to have protected the French journal L’Égypte in 1880–1881.85 Political change was accompanied by quickly changing ideas about solidarity, mixed with personal and business interests.

THE INVENTION OF HĀRŪN AL-RASHĪD: ARABIC THEATER AND LOYALISM

I propose to further explore political events through cultural history. This gives us the freedom to detect changes in ideology before they are manifest in social action. Between 1878 and the summer of 1882, there were performances of plays in Arabic that reflected these changes. These were performed for a relatively small and often a rather upper-middle-class or elite audience. The performances—apart from their economic or artistic goals—can be regarded as means of communication similarly to petitions. They asked for justice and solidarity from the ruler.

The Beiruti actors, left alone in Alexandria by Adīb and Naqqāsh, had to establish themselves in that city. One of them, Yūsuf Khayyāṭ, took over the leadership of the troupe.86 He was able to gain more popularity and even khedivial support in 1878–1879. This second Arab impresario instrumentalized a new means to build audience in Alexandria and Cairo, one that neither Sanua nor Unsī could make any use of in 1871–1872 in Cairo. This was charity.

The bourgeois connection between charity societies and theater had already been experimented with in Beirut. Now in Alexandria, this middle-class culture was further enhanced: for instance, on 10 January 1878 the Syrian troupe performed for the benefit of the Patriotic Society for Aid (for the injured in the Ottoman-Russian war) at the Zizinia Theatre. The growing number of Syrian migrants helped Khayyāṭ since they transferred their philanthropic activities to Alexandria and Cairo. We shall see in the next chapters that a working relationship developed between charity societies and Arabic theater in the 1880s.

Second, Khayyāṭ and the future Arab impresarios never gave up the pursuit of what had originally been agreed between Draneht and Naqqāsh about khedivial support. In the atmosphere of growing discontent in 1878, Ismail hastily turned to all available means to gain popularity: his interest now was to become truly the “father of Arabs.” This did not mean proper financing, only symbolic occasions were arranged. Khayyāṭ thus was able to collect on the agreement between Draneht and Naqqāsh.

Khayyāṭ’s troupe performed an Arabic piece in the Khedivial Opera House in February 1878 in the presence of Ismail. This was the first Arabic play staged in this symbolic space. The performance was Mārūn Naqqāsh’s Abū al-Ḥasan al-Mughaffal aw Hārūn al-Rashīd (1849), one of the most sophisticated Arabic musical plays in the nineteenth century. It is a musical comedy based on the 1001 Nights tale of al-Nāʾim wa-l-Yaqẓān usually translated as “The Sleeper Awakened.” It is a love story about Abū al-Ḥasan, a foolish older drunkard in Baghdad who is tricked by the caliph by making him believe that he rules Baghdad, although for only one day. The confused and petty Abū al-Ḥasan just brings disaster on himself. Hārūn al-Rashīd reappears at the end, reveals himself, explains the trick, and generously gives him money.87

The play contains references to the Ottoman context. At the end, Hārūn al-Rashīd is called a sulṭān and amīr al-muʾminīn and is portrayed as a generous and just ruler who helps the lovers, forbids the wrong, and rewards loyalty. At the time of its first staging in 1849, the Beiruti elite, as we have seen in chapter 1, could read the character of Hārūn al-Rashīd as a reference to Sultan Abdülmecid. However, in February 1878 in Cairo, in the Khedivial Opera House, the character of this caliph might have been a symbol for both the khedive and the sultan. This character would serve as the central hero of Arab patriotism in the khedivial opera in the 1880s. But even if it was a metaphor of the Ottoman sultan, an independent, strong, but benevolent ruler sent a clear message to the Ottoman Egyptian audience in early 1878 when the Ottoman-Russian war was being fought and the Debt Commission challenged the khedive’s power.

The performance of Hārūn al-Rashīd was the second instance of Ismail’s recognition of Arabic theater after Sanua’s briefly encouraged enterprise, at a time when Draneht lived abroad. Compared to Sanua, Khayyāṭ’s troupe was professional. This professionalism meant the use of fuṣḥā, well-chosen historical topics, and learned performance techniques.

Khedive Ismail and Arabic Theater

Khayyāṭ toured Cairo once more, first performing at the Comédie in front of Ismail Pasha, then at the Opera House, where the main attraction of his repertoire was again Hārūn al-Rashīd, attended again by Ismail, his family, and a number of ministers on 21 January 1879.88 These performances mean that Ismail and his elite considered Khayyāṭ and the troupe as appropriate, and, most importantly, loyal to the khedivate.

Al-Afghānī appeared also in the theater audience in the spring of 1879. This is the moment when Syrian artists further developed the idea of Mārūn Naqqāsh in musical theater by not only studying Egyptian tunes but in fact also involving Egyptian singers. This meant the recognition that Egyptian tunes had to be performed by an Egyptian, with proper Egyptian pronunciation, and, perhaps most important, by someone with a wonderful voice. In May 1879 in Alexandria, when Salīm Naqqāsh, in a momentary return to the theater, put on a play in the Zizinia, the famous female singer al-Sayyida Bazāda took part in the performance. This is the first known instance of the involvement of an Egyptian (female) singer in an Arabic theater performance. The performance was attended by Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī and the governor of Alexandria, Mustafa Fahmi Pasha.89 Was this a belated gesture, showing al-Afghānī’s support for the khedive?

However, the overthrow of Ismail and the closure of khedivial theaters thwarted Yūsuf Khayyāṭ’s plans. The troupe, or at least Khayyāṭ, remained mostly inactive until 1881. The period saw the development of three features, which will remain characteristic of Syrian intellectuals and actors in Egypt: their ability to reach the khedive (but unsuccessful institutionalization), their cooperation with Egyptian singers, and their attempts to achieve an Arabic historical repertoire to unite the audience through the celebration of a past hero.

The Play Homeland: Theater as a Means of Patriotic Petition

As Avriel Butovsky emphasized, “when Tawfiq came to power, new ways of thinking about the relationship of the khedive to society and the process of social change had come into the public sphere.”90 The break-up of Khayyāṭ’s troupe does not mean that there were no more occasions for communal experiences and communications to the khedive through Arabic performances. In fact, from around 1879, Arabic theater became an integral part of public patriotism. Between 1879 and 1882, Egyptian playwrights offered new imaginative representations about the community. They were, unlike the Ottoman Syrians, explicit about waṭan being “Egypt;” and it was an Egypt inhabited by “Arabs.” The new ruler Tevfik was attentive at the beginning.

The first Egyptian play that can be considered a petition was the work of ʿAbd Allāh Nadīm, a former telegrapher and poet once in the service of Hoşyar Hanım. In 1879 he established the first patriotic Muslim Egyptian society for teaching the poor in Alexandria, and there he also created a dramatic society and group. Nadīm, a man of linguistic virtuosity, a “literary bohemian,”91 wrote a play entitled al-Waṭan wa-Ṭāliʿ al-Tawfīq (“The Homeland and the Star of Success,” a pun on Tevfik’s name). The play was first staged in April 1880 in Nadīm’s school, then in July in the Zizinia Theatre before Tevfik and a number of dignitaries, including ʿAlī Mubārak. The school and the society had a record income on this occasion: Tevfik alone donated 100 LE and an additional total of 350 LE was raised.92 Compare this with the monthly sum of 8 LE, the relatively high salary of Ibrāhīm al-Hilbāwī, as an editor of the official bulletin in this year.93 Seemingly, al-Waṭan and the cause of the school attracted support.

The reason for this success is that the play discloses a patriotic conception in which the ruler and the poor are united. There are hints that this union is against the European Dual Control (called in Arabic kumsūn, “commission”)94 or against the rich (al-aghniyāʾ). The play calls for general education and for the establishment of patriotic societies. Contrary to the later female gendered images of Egypt as a woman,95 in this first theatrical anthropomorphization the Homeland is an old man. He sits on stage and listens to the dialogues between various representatives of the people, such as peasants, hashish addicts, or urban educated individuals. They do not recognize Waṭan as the Homeland (in a funny moment one character says būnū suwār yā Musyū al-Waṭan—“bon soir Monsieur Homeland”).96 He tries to open their eyes, at one point crying out: “where are my people, where are my children, where are my men, I have become lost in my cause, I do not know what may happen to me”;97 or, “you are my people and you left me.”98 Some recognize him and his message; one character confirms “I say to God oh brothers . . . that we all belong to one homeland.”99 While the poor complain about food and scarcity of resources, Waṭan condemns them for their ignorance and says that if they would unite their forces (“if you would agree on one word”) and turn to the government or “the greatest leader” (al-raʾīs al-akbar) they would surely receive help.100 Finally, the representative character of the educated patriots, ʿIzzat Efendi, who works at an embassy and knows foreign languages, decides to establish a school by gathering support and donating a small amount in “the age of success” (or “age of Tevfik,” ʿaṣr al-tawfīq, again a pun on the name of Tevfik).101 When even idle and poor characters decide to send their children to this school with the support of Efendīnā (the khedive), the play turns into a celebration of Tevfik. Its last sentences wish “a happy khedivial day” (yawm al-khidīwī saʿīd) and warns that all should turn to “look at the prince.”102 We can imagine the effects of these last words in the theater where the ruler was present.

Compared to the theatrical fashion of the time, al-Waṭan is exceptionally ahistorical and without music, but it is didactic and evokes the khedive. It is, as if it was written directly to teach the use of nation-ness to the ruler, almost in the mode of a medieval mirror for princes or a petition. Nadīm masterfully characterizes the protagonists with their dialect,103 but Waṭan and the Arab (Bedouin) talk mostly in pure fuṣḥā. This work poses a problem to teleological histories of national revolt and is usually left out;104 even Samah Selim, who analyzes the play for its image of the peasant, remarks that “the play begins and ends with an extended dialogue between them [Homeland and the peasants].”105 But this is not the case. The play ends with a praise sang by girls to the khedive and the calling of all the “Arabs” to watch the prince.106

There were other attempts to involve the ruler in patriotic activities related to education and theater. Copts also put on a school play at the Zizinia and at the al-Qubārī school in the presence of Tevfik, both in August 1880. There were other school plays in Alexandria, in the Qardāḥī-school (see below). These were also the years when ʿAlī Mubārak published his novel ʿAlam al-Dīn with the chapter praising the theaters that was already quoted. The Jewish Charitable Society asked Yūsuf Khayyāṭ to help in staging the play Ḥifẓ al-Wudūd at the Opera in April 1881. This performance might have increased the value of Arabic theater for nurturing nonsectarian patriotism. This time Khayyāṭ also submitted a request to use the Comédie in Cairo in the coming theater season. This was granted, but the financial aid—Khayyāṭ asked for 6,000 LE107—was refused.108 The lack of financial support especially hurt because the government subsidized the foreign troupes in the Opera and the Comédie with 225,000 francs in the 1880–1881 season.109 However, adding these to Nadīm’s theater activity there was a remarkable interest in theater.

Exactly at the moment when Khayyāṭ’s sponsorship was rejected, Tevfik asked ʿAbd Allāh Nadīm to restage al-Waṭan in the Zizinia in July 1881. This proved a dismal failure because the enemies of Nadīm, perhaps at the instigation of Riyaz Pasha, did their utmost to discourage the audience. There is no clue why Riyaz opposed Nadīm when he had previously supported dissent as in the case of al-Afghānī, ʿAbduh, and al-Hilbāwī. Nadīm the next day resigned from the school and the Islamic Charitable Society.110 This event may have contributed to Nadīm’s turning to the rebellious army officer Aḥmad ʿUrābī, who asked him to travel in the countryside to deliver patriotic speeches in his support in the following spring.111

Arabizing the Egyptian army

A political crisis accompanied the cultural stirrings. The Egyptian army, led by colonel Aḥmad ʿUrābī, demanded the restoration of their pensions and the sacking of the European advisers. The summer of 1881 continued with a troubled autumn. On 23 September 1881, the army openly demonstrated in front of the Abdin Palace against French and British control and against their pay cuts. The army became the central force to unite all dissenting challengers, and created “a coalition” of forces which is a condition of an action field.112

Now the government made a more conscious effort to collect support through the Arabic public sphere. Although journalism is often counted as a revolutionary activity in the period, the government in fact paid 2505 subscriptions in 1881 to various journals (al-Ahrām 336, al-Waṭan 265, al-Burhān 232, al-Maḥrūsa 235), which was possibly both support and control.113

In addition, Tevfik received Yusūf Khayyāṭ at a private audience and allowed him to perform at the Comédie from November 1881 to January 1882. Now ʿAbd Allāh Nadīm once more tried to reach the khedive, by giving a speech when Khayyāṭ’s troupe staged again the play Hārūn al-Rashīd in front of Tevfik. However, the attendance was poor.114 In January 1882 Khayyāṭ’s troupe dissolved, and Nadīm eventually turned into the “orator of the revolution.”

The army then entered the public sphere. Nadīm started to print a satirical journal, al-Tankīt wa-l-Tabkīt, between July and October 1881; and now was editing al-Ṭāʾif (from November 1881 to the summer of 1882). In these journals he called ʿUrābī a “hero” (fāris) and ridiculed the efendis who imitated the European life-style. An explicitly pro-military journal was al-Ḥijāz (July-November 1881), edited by a certain Ibrāhīm Sīrāj al-Madanī, a Muslim scholar from Medina, who bought his press in Cairo on money from the officers of the 3rd Infantry in the Citadel.115 It was known as “the journal of the colonels” and finally was suppressed by the government. Al-Ḥijāz praised the new laws after the army demonstration in September 1881 by employing Muslim symbols and figures of speech both in prose and in poetry. Al-Madanī advertised a favorable Muslim Arab image of the army: “our army places the claims of humanity and the state above personal interests,” and even praised Tevfik’s (in reality Riyaz’s) economic measures. There were articles about Arab greatness in Andalusia, the past Arab empires, the British in India, and the contemporary French occupation of Tunis and Algeria. The editor also published the letter of the Azharite Sheikh Ḥasan al-ʿIdwī to the sultan which accompanied his book-gift to Istanbul in 1881. Al-Madanī connected Islam, moral and racial categories whose embodiment he found in the Egyptian army within the Ottoman frames.116 This ideological description made the army the representative of patriotic defense, the ideal symbol of nation-ness constituted by Islam and empire.

THE ARAB OPERA

The experience of patriotism occurred in the theater again. The general discontent and the army grievances prompted Tevfik to appoint a new government in February 1882 led by the poet and soldier Maḥmūd Sāmī al-Bārūdī, and in which Aḥmad ʿUrābī became minister of war (in reality he was the strong man in the government).117 ʿAbd Allāh Fikrī became minister of education and his undersecretary was ʿAlī Fahmī. That spring saw increased struggle between the European controllers, ʿUrābists, the khedive, and constitutionalist zevat and aʿyān. Tevfik approved an Organic Law for the Assembly of Deputies in February 1882 which brought all legislation and contracts of Egypt to the power of the Assembly. While it has been regarded as a constitution, it does not regulate the status of the ruler, his dynasty, nor does it announce popular sovereignty, or deal with the status of Egypt as an Ottoman province.118

There was a conflict within the army between the “Turks” (or “Circassians”) in leading positions and the “Egyptians.” In this closing section, we continue following intellectuals and artists and their relation to power in an increasingly unstable atmosphere.

The Patriotic Munshid: Salāma Ḥijāzī

Revolutions are lucrative periods for the arts. The career of the most important singer-actor in fin-de-siècle Egypt starts during the spring of 1882. Unlike ʿAbduh al-Ḥamūlī, whom we met in chapter 2, Salāma Ḥijāzī lacked the khedivial touch; he is not known to have sung for the khedive, or to have been exposed to late Ottoman culture. In contrast to ʿAbduh al-Ḥamūlī, “the nightingale of weddings,” Ḥijāzī was later often described as “the village headman” (ʿumda) of the Arabic theater. He was fully immersed in nonofficial Egyptian Muslim culture. He was a munshid, a half-religious half-entertaining singer from Alexandria. His career gives a model of patriotic entertainment through local Muslim traditions.

Ḥijāzī’s father died early, and the child, raised by a barber, was supported by a leader of a Sufi order (the Raʾsiyya). He participated in Sufi ceremonies and festivals, and also knew the Koran by heart at the age of eleven. He was taught by Aḥmad al-Yāsirjī, Khalīl Muḥarram (the leading singer in Cairo, ʿAbduh al-Ḥamūlī was once in his troupe), and Kāmil al-Ḥarīrī, all famous munshidīn of the time. He became the leader of the Raʾsiyya at a young age, and, although he was not trained, Ḥijāzī announced regularly the morning prayer in a neighborhood mosque in Alexandria. At the age of twenty-two he married a girl named ʿĀʾisha and soon Muḥammad their first child was born, who died early. Perhaps because of the need to finance his family he formed a takht, a group of musicians, with whom he performed in popular celebrations and marriages.

There is uncertainty, even by those biographers who knew him in person, how Ḥijāzī transitioned from a munshid in the 1870s into a theater star in the 1880s.119 This uncertainty, I suggest, is deliberate. Oftentimes the narratives emphasize that Salāma Ḥijāzī stepped on stage after the ʿUrābī revolution (1882). He himself remembered once that he had made up his mind about musical theater only around 1884 and after a discussion with al-Ḥamūlī and his musicians in the presence of Khedive Tevfik.120 This memory was an attempt to connect his rise to a politically loyal setting. Yet Ḥijāzī had already performed for Aḥmad ʿUrābī in Cairo during the spring of 1882.

Ḥijāzī must have been performing even earlier. It is said that, being in Alexandria, Ḥijāzī first thought that the modern theater was a condemnable innovation (bidʿa) and rejected the first enquiries from Naqqāsh or Khayyāṭ in the late 1870s.121 In his earliest biography, his first role was Horace (Kūriyās) in Salīm Naqqāsh’ Mayy, arranged by his “teacher” of acting, Sulaymān al-Ḥaddād, yet another Syrian intellectual.122 There was one performance of Mayy by Sulaymān al-Ḥaddād on 4 June 1881 in Alexandria,123 which may have been Ḥijāzī’s first performance. He in fact remained attached to the Ḥaddād family through his life.124 This attachment did not prevent Ḥijāzī from “forgetting” his performances in front of ʿUrābī, for which the explanation must be the fear of punishment after the failed revolution. We shall see in the next chapter that in the 1880s he actively participated in rebuilding an Arabic façade for Khedive Tevfik. His origins, education, and social setting contributed to his public patriotic image and leading role in the musical theater.

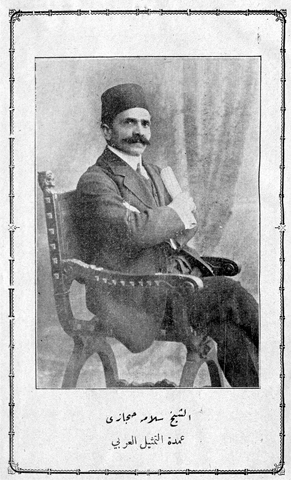

FIGURE 5.1. Sheikh Salāma Ḥijāzī, possibly in 1913

Source: al-Ḥaddād, Muntakhabāt, unnumbered [2].

Qardāḥī and the Establishment of the Arab Opera

Sulaymān Qardāḥī’s life, by contrast, is an example of mobility in the eastern Mediterranean, or better to say, in the whole world, since he lived for a short time even in South America (see next chapter for his later years). Qardāḥī was born in Dayr al-Qamar in Mount Lebanon into a Christian Arab family.125 He was already an orphan in 1860 at the time of the bloody conflict in Mount Lebanon and Damascus. The young Sulaymān was then educated in France.126 It is not known when he returned to Beirut or when he migrated to Egypt from there. He may have participated in Naqqāsh and Khayyāṭ’s troupes and was possibly related to another actor, Sulaymān Ḥaddād, the first acting “teacher” of the singer Ḥijāzī.127 Christine Qardāḥī, Sulaymān’s wife, established a “Patriotic School for Girls” (Madrasat al-Banāt al-Waṭaniyya) in Alexandria in the late 1870s. Sulaymān Qardāḥī worked for the journal al-Ahrām in 1879.128 He also put on plays in Arabic and French with the pupils (girls) at the end of the school-year celebrations in 1879 and 1880.129 However, as opposed to Adīb, Naqqāsh or even Ḥijāzī, he had no creative talent: he was not a translator, playwright, or a singer. His talents seemingly were acting and, foremost, management.

Qardāḥī involved women in his theater troupe. In February 1882 he established a troupe in Alexandria with two women: his wife, Christine, and an actress or singer, called Ḥunayna who may also have been a relative.130 He himself took to the stage, and Anṭūn Khayyāṭ, the brother of Yūsuf, may have also have been a member of the troupe.131 His greatest addition was the singer Salāma Ḥijāzī, who in association with Qardāḥī would become a widely known artist. Other, presumably Egyptian, singers (Sheikh Maḥmūd and Sheikh ʿAlī) also performed with them. Music defined the new troupe: it became known as the Arab Opera (al-Ūbira [!] al-ʿArabī).

The Arab Opera and Politics

The alliance of Syrian actors and Egyptian singers in the production of patriotic entertainment was an answer to the ʿUrābist atmosphere. During February and March 1882, under the Bārūdī-government, in Cairo and Alexandria societies and notables held gatherings and evenings, where the two central Muslim figures, ʿAbd Allāh Nadīm and Muḥammad ʿAbduh, gave patriotic speeches and demanded constitutional government (al-ḥukm al-qānūnī). In this tense political atmosphere, an advertisement appeared in the Arabic press in 28 March 1882, calling the patriotic notables of Cairo to the performances of the Arab Opera:

An Arab Opera will be presented in the capital’s Opera [House] in the middle of April [18]82, under the leadership of its director, Sulaymān Qardāḥī. [This troupe] consists of twenty-five individuals who are the most famous singers with pleasant voice and with perfect declamation and theatrical abilities. . . .

I [Sulaymān Qardāḥī] proceeded with this theatrical art whose joyful excellence and educative (adabiyya) advantage is not hidden from you. Thus I have arranged an Arab troupe with a special consideration for the performing skills of the participants, their pleasant voice, and their perfect declamation. I have also chosen good and gentle plays for this art, sacrificing money, working day and night in order to perfect it.132

The Arab Opera’s guest evenings in Cairo may have not been entirely Qardāḥī’s idea. There must have been an informal connection between Qardāḥī and the military engineer Maḥmūd Fahmī, the minister of public works, who was legally responsible for the Opera House (see chapter 7). Qardāḥī’s official request for the free use of the Opera House is dated 25 March 1882, yet the previous day al-Ahrām had already published the news that the troupe had received permission to use the Opera House gratis, from Maḥmūd Fahmī, who even promised to pay for the gas lighting.133 Qardāḥī in his written request asked for eight evenings, the necessary equipment, and the gas.134 The ministry granted the request, however, on condition that he “should conform to the current regulations.”135

This was the first Arabic “season” in the Khedivial Opera House. Qardāḥī emphasized the political utility of theater. In his application, he argued that his troupe was a patriotic (waṭanī) enterprise. He wrote to the minister of public works that “I have started to teach some Arabic plays to an Egyptian troupe,” although it may have contained more Syrians than Egyptians. The Arab Opera was considered in the Syrian-owned Arabic press as an expression of patriotism (waṭaniyya), mostly in the journals al-Ahrām and al-Maḥrūsa.136 On the other hand, the Egyptian-owned periodicals in print during the spring 1882 (al-Kawkab al-Miṣrī, al-Burhān, al-Ittiḥād al-Miṣrī, al-Mufīd, al-Muntakhab, al-Najāḥ, Nadīm’s al-Ṭāʾif, al-Zamān, al-Waṭan) either do not mention Qardāḥī’s troupe or are not available today. This silence remains curious. Was there a competition between Syrian and Egyptian intellectuals for representing patriotism?

ʿUrābī and ʿAntar

Since there was an irreconcilable political tension between the khedive, the foreign advisers, and the Egyptian army officers, public events carried extra weight during the spring of 1882. It seems that there were moments of temporary balance. The equilibrium was expressed in cultural terms through the public performances of Qardāḥī. This is the time when a new hero replaced Hārūn al-Rashīd. This is ʿAntar, an ancient pre-Islam warrior and poet, who would serve as a symbol for Aḥmad ʿUrābī. The warrior replaced the caliph as symbol of unity.

The Arab Opera performed in the Khedivial Opera House altogether on seven evenings and one public rehearsal (Qardāḥī advertised only six performances but gave one encore).137 Their repertoire consisted of four plays: Tilīmāk (Telemachus), Fursān al-ʿArab (The Arab heroes), Zifāf ʿAntar (The wedding of ʿAntar), al-Faraj Baʿd al-Ḍīq (The release from suffering). Three of these plays feature a hero: Tilīmāk (Telemachus) and the legendary ʿAntar. ʿAntar (or ʿAntara) b. Shaddād was a pre-Islamic poet and warrior in Arabia whose life and battles (Sīrat ʿAntar) were enshrined in oral and written poetry. Arab coffeehouse culture had cherished storytellers who read aloud the manuscripts of “The Life of ʿAntar.”138

The hero ʿAntar (on stage portrayed by Salāma Hijāzī) and Colonel ʿUrābī offered a potential symbolic pair. In my interpretation, both ʿAntar and ʿUrābī represented fighters who resisted oppression and injustice. It is worth remembering that Said Pasha also loved the story of ʿAntar, and Said’s time was a good period for the young ʿUrābī.139 The portrayal of the martial virtues of an Arab warrior must have been well received among the army officers in the government.

The political context, however, alludes to a more complex understanding of the image of the hero. April 1882 started with a strike of coal heavers in Port Said, one of the first modern workers’ strikes in Egypt.140 Though possibly unconnected, the first performance of the Arab Opera was delayed for a week and coincided with yet another important event. This was the discovery of a presumed plot against ʿUrābī Pasha on 11 April 1882. Most of the men arrested were of Circassian or Turkish origin. Salīm Naqqāsh in his pro-dynastic chronicle, written just after the revolution, remarked that the people in Cairo were terrified when the news arrived.141 A military committee investigated the issue, while, according to the memoirs of Maḥmūd Fahmī, the ʿUrābists tortured the accused officers in the prison of the Citadel.142 Finally, forty-two officers were condemned to death. Khedive Tevfik, however, intervened and changed the sentence to exile to the Sudan.143 While the performances of the Arab Opera were cheered in the Opera House during April, this trial was possibly the major talk of the town as we can see in table 5.1.

The performance of Zifāf ʿAntar on 23 April was especially successful: the audience was so enthusiastic that they demanded the repetition of the third act with Salāma Ḥijāzī. The journals highlighted the bravery of ʿAntar and the gentleness of the acting and voice of Sheikh Salāma. Other actors, especially Christine Qardāḥī, were also praised. Al-Maḥrūsa, Naqqāsh’s journal, did not miss the opportunity to underline that this art was so far the privilege of Europeans and expressed hope for more government support for Arab acting. Meanwhile, the military investigation proceeded, and more suspects were arrested, now numbering to 48, but there were rumours that as many as 150 officers had been taken into custody.144

TABLE 5.1. Political Events and the Performances of the Arab Opera, April 1882 |

|

Performances of the Arab Opera, 1882 |

Political Events in Cairo, 1882 |

13 April—Tilīmāk |

11 April—arrest of Circassian/Turkish soldiers |

16 April—al-Faraj baʿd al-Ḍīq |

|

(19 April a private rehearsal) |

around 20 April—trial |

20 April—Fursān al-ʿArab |

|

23 April—Zifāf ʿAntar |

around 22 April—sentence to death (khedive intervenes) |

28 April—Tilīmāk |

28 April—sentence to exile in the Sudan |

30 April—Fursān al-ʿArab |

30 April—public announcement of exile |

The bravery of ʿAntar, a black slave turned tribal hero, embodied by Ḥijāzī, had the potential of a powerful political allegory for the new leader. The last performance of the Arab Opera, Fursān al-ʿArab (The Arab heroes) took place on 30 April 1882. This was yet another play about ʿAntar, the hero. Since ʿUrābī Pasha was also called a hero (fāris) in the periodicals of ʿAbd Allāh Nadīm, this play can be seen as a subtle statement to support him. On this evening, the actors were cheered and continuously asked for encores by a clapping audience. This was the day when news of the exile of the forty-eight army officers to the White Nile was released. After the performance, Qardāḥī, as the director of the group, stepped on stage and greeted ʿUrābī and thanked him for the support of the government. This was an important gesture, because so far the khedive had been thanked by impresarios (Sanua, Naqqāsh, Khayyāṭ), even if he had not done anything. And in fact, not ʿUrābī, but Maḥmūd Fahmī, minister of public works, had provided the support for the troupe. Furthermore, other statesmen in more elevated positions were present in the Opera, such as the president of the National Assembly (Majlis al-Umma), but they were not mentioned in Qardāḥī’s speech, or, at least, not in the reports.145

THE UMMA AND THE SHAʿB: “A GARDEN WITH MELLOW FRUITS”?

Before concluding with the well-known story of the 1882 summer events, the revolution that led to the British occupation, it is worth highlighting a competition that discloses two ways of imagining an Egypt without a khedive. Two petitions for the concession of the Opera House and the Comédie contain these unique patriotic proposals. The petitions were prompted by the fact that the Bārūdī government had decided upon a 9,000 LE subsidy for the following theater season (1882–1883).146 The petitions highlight a possible trajectory of the non-khedivial state culture in Egypt and a competition between Arab theater directors.

The first one arrived from Yūsuf Khayyāṭ and ʿAbd Allāh Nadīm from Alexandria. This unexpected couple submitted a request in April 1882 for the free use of the Comédie. They wanted to offer forty evenings during five months in the following theatrical year. The Syrian Christian impresario and the Egyptian Muslim intellectual requested the costumes, the building, and the right that during their concession no one else would stage theatricals in Cairo without their prior consent. This last element may well have been due to the competition between Arab troupes. The theater monopoly, requested by Khayyāṭ and Nadīm, entails a regulation of the market with help from the state.

In the Khayyāṭ-Nadīm short proposal, theater, “the art of representing historical events” (fann tashkhīṣ al-waqāʾiʿ al-taʾrīkhiyya), is “among the enlightened means [to produce] ever-circulating ideas.” In their view, education in advanced states is conducted through scenes “about their own history, in the language of their people, including some events of the other nations;” so “as a result understanding [theater] is easy because their people already possess the capacity to grasp the essence of the play.” In this conception, before using theater as an educational means, it has to match the people’s language (no reference to which form of Arabic) and history. The keyword is umma or umma miṣriyya (translated here as “people”). Khayyāṭ and Nadīm add that until this moment “no Egyptian troupe was formed among the Egyptian people that would conform to their own language and their own manners.” This later remark implies that these two intellectuals did not consider the troupes of Sanua, Naqqāsh, Khayyāṭ’s own, and Qardāḥī’s as Egyptian or conforming to Egyptian manners, or, at least, they wanted to convince the government of this.147 It is remarkable that Khayyāṭ and Nadīm professionally highlighted the main components of patriotism: language and history.

Another request arrived from the victorious impresario Sulaymān Qardāḥī. With the encouragement of the minister Maḥmūd Fahmī, he proposed to perform fifteen different theatrical pieces in Arabic, with thirty actors and fifteen actresses in the Comédie in the next season. Qardāḥī described his efforts and losses that he sacrificed to establish the “Patriotic Arab Troupe” (al-Jawq al-ʿArabī al-Waṭanī), another name for the Arab Opera. This remarkable letter is not simply another offer for the government to promote theater as a means of education but is also a personal expression of devotion to theater in Arabic:

Indeed, a strong zeal for this fine art has taken me to try to use it in Arabic until we will be able to [perform plays] in our language perfectly and we won’t need [theater] in foreign languages anymore. . . . I was sure that if I asked the Exalted Government it would give a helpful hand when I notify the leaders about my zeal in refined education (adab) and my passion for the renewal of this useful project.

In this letter Qardāḥī understood theater as a “garden with mellow fruits,” providing knowledge to which everyone has access. He also requested money for the translation of “historical and scientific books.” Coming from a school environment, based on the Beiruti tradition, similar to Khayyāṭ-Nadīm, to his thinking theater was an instrument of education. But in contrast to Khayyāṭ-Nadīm, Qardāḥī deployed other ideas to describe the people who are to be educated: they are not umma, but they are shaʿb (people) or ahl al-bilād (the locals) or jumhūr (the public). None of these words have religious connotations. Thus his theater would not only educate the people, but this education would also contain a sense of nonreligious equality. His main intention was to produce “well selected plays which suit the taste of the people and are useful for the public.” In locating the taste(s) (adhwāq) of the Egyptians, Qardāḥī found music indispensable: he wanted to improve performances through the study of Arabic singing, and have more actors and actresses, with musicians. To boost the troupe, he requested financial support from the government, though he also expected the “wealthy” of the country to contribute. In his words, this was a musical enterprise that would result in “public benefit” (fāyida [fāʾida] ʿumūmiyya).148

The khedive is missing from the submissions of Khayyāṭ-Nadīm and Qardāḥī—this would have been unimaginable even a year earlier. There is no mention of dynastic support; they presented patriotic conceptions only to the government. Both petitions assume a concept of community, and both imagine this community to be taught by the government through the theater. The proposals themselves were already part of education, explaining the meaning of theater to Maḥmūd Fahmī, the minister, who was a military engineer. The use of umma and shaʿb distinctively does not disclose major differences at this moment, though Qardāḥī’s shaʿb has no religious connotations. While Khayyāṭ-Nadīm thought language and history to be the main features of patriotism, Qardāḥī emphasized the role of music to match “the taste” of the people. These Arabic submissions were never answered.

THE LAST ACT

At about the time when Qardāḥī and Ḥijāzī left Cairo in May 1882, at a gathering of Egyptian notables (many of them from the Consultative Chamber), the army officers demanded to depose Tevfik and to ask for a new khedive from Sultan Abdülhamid II. The notables declined first, preferring a compromise.149

The political tension resulted in a riot in Alexandria. The events accelerated with foreign intervention invited by Tevfik. After the British bombardment of Alexandria on 11 July, the khedive, who had secretly urged the bombing,150 declared ʿUrābī a rebel on 24 July.151 A few days later, an assembly of notables and army leaders announced that Tevfik had “deviated from the rules of God’s noble law and the sublime law [of the sultan]” (kharaja min qawāʾid al-sharʿ al-sharīf wa-l-qānūn al-munīf) and requested a new khedive from the sultan.152 Within the army, the decision was explained that “the khedive had betrayed the nation” (al-khidīwī fī khidāʿ al-umma) and “he sided with the British instead of returning to our Exalted [Ottoman] State which entrusted him with this glorious emirate.” The leaders asked that the decision be passed on to all soldiers and “every single member of the Egyptian nation (umma).”153 Empire was an argument for Egyptian nation-ness at this moment.

The 24 July decision, signed by learned patriots such as ʿAbd Allāh Fikrī and ʿAlī Fahmī, indicates the complete breakdown of Tevfik’s authority but not the breakdown of the Ottoman khedivate as an institution. On the contrary, the rebels claimed that they were supporting the Ottoman caliph. Abdülhamid II suspected, though, that ʿUrābī was paying only lip service to his authority (the sultan seems to have favored Abdülhalim as a new khedive at the time).154 Finally, the sultan denounced the Egyptian general as a rebel.155 Qardāḥī and his family rushed back to Beirut with other migrants, including Naqqāsh and Khayyāṭ. Hijāzī with his family hid in Rashīd (Rosetta) to become a muezzin in the Zaghlūl mosque.156 The Arab Opera dissolved. The British army occupied the province of Egypt.

CONCLUSION: THE RETURN OF THE EMPIRE

There were competing visions of what the khedivate was. Local intellectuals nurtured various ideas, of which the defining one was that it was a polity whose official language is fuṣḥā Arabic and whose history is plural. The majority seems to have thought that it was a Muslim state with attachments to the Ottoman caliph. For Ismail himself, the khedivate was all of these but most importantly a security measure against pretenders. Critical thinking typically aimed at the improvement of the khedivial system, to achieve an “enlightened despotism” to use the words of Adīb and al-Afghānī. Politically, the main breaking point seems to have been the acceptance or rejection of British and French controllers vis-à-vis khedivial authority. The Ottoman Empire became important again for intellectuals in Egypt.

There are traces of a discursive competition for talking to the khedive in the name of the nation. Arabic-speaking nonlocal Ottomans and locals such as Nadīm used patriotism. A continuous communication in culture occurred through works addressed to the ruler. It is this effort that resurrected two powerful characters as symbols of justice and power: Hārūn al-Rashīd as an allegory of the khedive and ʿAntar as an allegory of ʿUrābī. Didactic works, such as Nadīm’s al-Waṭan, targeted the ruler and called for solidarity. Through these efforts, the discursive Arabization of the khedive developed further. In sum, the various representations, staging, and performance of Arabness point at a moral quality offered also to the Ottoman elite to be included.

The Egyptian army’s intervention into the affairs of governance made it possible to formulate national images in which the khedive no longer figured. In his place ʿUrābī appears as leader of the homeland. This change symbolizes a break in ideology, or, in the learned imagination about the army, since legally the khedive remained the leader of the army but his loss of control had already been expressed on the Arabic stage. This was an unprecedented development: a radical change in the realm of ideas before the actual revolt.

1 Reid, “The ʿUrabi revolution,” 220.

2 Mayer, The Changing Past; Di Capua, Gatekeepers, 172–174.

3 Reid, “The ʿUrabi Revolution,” 218.

4 Cole, Colonialism and Revolution, 268.

5 Landau, “Prolegomena.”

6 Sālim, Al-Quwa al-Ijtimāʿiyya; Schölch, Egypt for the Egyptians; Cole, Colonialism and Revolution.

7 EzzelArab, European Control; see his other articles in the following notes.

8 Khuri-Makdisi, The Eastern Mediterranean, 115–116; Fahmy, Ordinary Egyptians, 55–60.

9 Philipp, The Syrians in Egypt, 17–25.

10 Letter dated 16 March 1984, AAC.

11 Al-Khūrī received 1,000 wīntū, order dated 18 Jumādā al-Akhīra 1281 (18 November 1864), Sāmī, Taqwīm al-Nīl, part 3, 2:579. The subsidy for al-Jawāʾib and al-Jinān was reduced to 300 pounds in 1879, thus these journals must have received a larger amount before that date. Letter dated 20 January 1879, Maḥfaẓa 1, Juzʾ 2, Niẓārat al-Dākhiliyya, CMW, DWQ.

12 Al-Najāḥ, 9 Kānūn al-Thānī, 1871, 11–12; next number, 29–30, next number 43–45, next number 60–61 (khedivial music), next number 76–77; then 221–222.

13 Hanssen, Fin de siècle Beirut, 168.

14 Moreh and Sadgrove, Jewish Contributions, 68.

15 Sadgrove, “Syrian Theatre,” 273.

16 As Agent Z reported in his letter dated 27 January 1871 to Mr. Nardi, the Inspector of Police in Cairo in 5013–003022, DWQ.

17 Al-Jinān as quoted in al-Jawāʾib, 10 May 1871, 2.

18 Al-Jawāʾib, 27 March 1872, 2.

19 Leafgren, “Novelizing the Muslim Wars of Conquests,” 51–52.

20 [Al-Bustānī], “Al-Riwāyāt al-ʿArabiyya al-Miṣriyya,” 443.

21 Granara, “Nostalgia, Arab Nationalism,” 57–73.

22 Shaykhū, Taʾrīkh al-Ādāb al-ʿArabiyya, 106.

23 Sadgrove, Egyptian Theatre, 130; Najm, al-Masraḥiyya, 204–206. It is unclear when it was staged; it was produced together with his uncle’s play al-Bakhīl. An anonymous article in al-Jinān (Salīm al-Bustānī?) states that it was staged “after Salīm Efendi arrived from the mountain,” in “Al-Riwāyāt al-Khidīwiyya al-Tashkhīṣiyya,” al-Jinān, 1 Tishrīn al-Awwal (October) 1875, 694–696. Moosa believes that it was in 1868, Moosa, The Origins, 33; Sadgrove states it was in 1875, Sadgrove, Egyptian Theatre, 130.

24 Sadgrove supposes that the young man aided his uncle Niqūlā in performances. Sadgrove, “Syrian Theatre,” 283.

25 Naqqāsh, “Fawāʾid al-Riwāyāt aw al-Tiyātrāt,” 519–520.

26 Letter dated 10/22 June 1871, from Salīm al-Bustānī to Zaki Pasha, attachment to 219/48, Microfilm 205, MST, DWQ.

27 Sadgrove, Egyptian Theatre, 130. Moosa, The Origins, 34.

28 Revue de Constantinople, 13 June 1875, 594. It cites Phare d’Alexandrie as a source. Sadgrove refers to al-Jawāʾib, 16 June 1875.

29 [Al-Bustānī], “Al-Riwāyāt al-ʿArabiyya al-Miṣriyya,” 423.

30 Naqqāsh, “Fawāʾid al-Riwāyāt aw al-Tiyātrāt,” 520.

31 Abul Naga, Les sources françaises, 110; Garfi, Musique et Spectacle, 222.

32 Najm, Salīm Naqqāsh, page b.