TAKE ME TO THE RIVER

Forming a Plan

Between my age and my manifest lack of talent, it was clear that a bite-size approach was in order. Knowing what I do about language from my day job as a developmental psychologist, I also strongly suspected that my only realistic hope of learning to play an instrument was to become completely immersed. I figured that I had no more chance of becoming musical by playing three minutes every other week than I had of learning to fly. Kids who learn second languages in immersion programs do vastly better than kids with more occasional exposure, presumably because it takes the human brain a great deal of exposure to learn anything complicated, and we tend to forget the new stuff if we take too long between practice sessions to consolidate what we’ve learned. It is no accident that popular music education paradigms like the Suzuki method are based on immersion, and there is no reason to expect that adults would be exempt from the need for high doses of regular exposure.

Why is it that skills like music require such profound dedication?

The cognitive psychologist Anders Ericsson, the world’s leading expert on expertise, mentions two vital keys to becoming an expert in any domain. The first is a ton of practice. The oft-quoted figure “ten years” or “ten thousand hours” is based on Ericsson’s research into experts in domains ranging from chess to violin. This is not to say that one gets nowhere with five thousand hours, but there can be no doubt that there is a strong correlation between practice and skill.

But practice alone is not enough. Hundreds of thousands of people took music lessons when they were young and remember little or nothing.

The second prerequisite of expertise is what Ericsson calls “deliberate practice,” a constant sense of self-evaluation, of focusing on one’s weaknesses rather than simply fooling around and playing to one’s strengths. Studies show that practice aimed at remedying weaknesses is a better predictor of expertise than raw number of hours; playing for fun and repeating what you already know is not necessarily the same as efficiently reaching a new level. Most of the practice that most people do, most of the time, be it in the pursuit of learning the guitar or improving their golf game, yields almost no effect. Sooner or later, most learners reach a plateau, repeating what they already know rather than battling their weaknesses, at which point progress becomes slow.

Ericsson’s notion of practicing deliberately, not just fooling around but targeting specific weaknesses, bears some relation to an older concept known as the “zone of proximal development,” the idea that learning works best when the student tackles something that is just beyond his or her current reach, neither too hard nor too easy. In classroom situations, for example, one team of researchers estimated that it’s best to arrange things so that children succeed roughly 80 percent of the time; more than that, and kids tend to get bored; less, and they tend to get frustrated. The same is surely true of adults, too, which is why video game manufacturers have been known to invest millions in play testing to make sure that the level of challenge always lies in that sweet spot of neither too easy nor too hard.

My own journey began with what we call in my trade a pilot study— a relatively small-scale exploratory study to see whether further investment might plausibly pay off: two weeks, at the end of August. My wife’s family owns a lakeside cottage in Canada, which we visit nearly every summer, and I decided that this summer I would devote those two weeks to music and nothing else. Fresh from my modest success with Guitar Hero, six months shy of my thirty-ninth birthday, I decided that now was the time.

To our annual summer retreat I brought nearly every piece of musical equipment I owned. Just because I couldn’t play didn’t mean I couldn’t buy. I had a Casio keyboard, a cheap acoustic guitar (an eBay special), and a small pile of books on music, including Play Piano in a Flash! and The Complete Guitar Player, along with a pile of ear-training applications on my cell phone. And I was serious about the immersion: I practiced every day, two, three, four, even six hours a day, roughly half on piano, half on guitar. Because I was a complete beginner, my goal was simply to become acquainted with some of music’s most basic elements, individual notes and, especially, chords, which are combinations of three or more notes played together.*

The rudiments of piano came relatively easy; guitar was brutal. On piano, it’s easy to find the notes and form the basic chords. Every twelve keys the same fundamental pattern repeats. The white keys play the notes C, D, E, F, G, A, and B before repeating; the black keys in between play the so-called sharps and flats, such as C-sharp and B-flat. Place your fingers on C, E, and G, and with those three notes you’ve formed your first chord, the C major triad. With a pair of simple rules it became relatively easy to play any of the major and minor chords. One can always form a major chord, for example, by starting with some particular note, known as the root, and then counting four keys (both black and white included) to the right, and then heading up three more.

C major, for example, is formed by starting with C, heading to E, and ending with G.

Following the same rule but starting from D, one counts up to F-sharp and A, yielding the three notes in the chord of D major: D, F-sharp, and A. It seemed so simple.

As straightforward and mathematical as piano is, I knew it wasn’t the instrument for me. I had spent enough of my life at a keyboard already. Something about the physical intimacy of plucking guitar strings called to me. The guitar was obviously going to be harder to break into, but within a week or two I was convinced that it was the instrument I really wanted to play.

At first, I regretted my decision. Everything, even something as simple as playing a single note all by itself, seemed harder on the guitar. Whereas playing an isolated note on a piano requires nothing more than striking a key, playing a single note on the guitar (unless it’s a so-called open string) generally requires two actions, one from each hand, coordinated in synchrony.

For a right-hander such as myself, the left hand does the job known as fretting, which means holding down the right set of strings at the right time at the right place along the neck of the guitar. Frets are the thin metal wires that run across the narrow width of a guitar’s neck. The left hand’s mission is to clamp the strings down, close to the upper side of a given fret— not halfway between frets, as a beginner might imagine— so as to minimize extraneous vibrations. Meanwhile, the other hand (right for a right-hander) has the job of plucking or strumming the strings. (At first this all seems backward, since the weaker hand has to contort itself into all sorts of rapid shapes; it’s only when you start fantasizing about playing flamenco that you see how hard the job of the right hand can become.)

Playing a chord is even more complicated, in part because you can play only one note on any given string at any one time; forming a chord requires you to form weird left-hand shapes that span across several strings. Even if you know the four-up/three-up mathematics of how to form a major chord on a piano, it’s often not at all immediately obvious where to find the requisite notes on the guitar; instead, the beginner has little choice but to memorize an obscure series of shapes. And even once one memorizes where one’s fingers are supposed to go, there is the by no means trivial matter of holding them all down at the same time, each perfectly aligned, without creating a foul noise known as fret buzz. For the first several weeks, that challenge alone seemed almost insurmountable; the idea of shifting my hand from one chord to the next in time with a song seemed almost comical.

Yet somehow I remained undeterred. The weather by the lake was nice, and much to the amusement of my in-laws, I kept at it, practicing every day— rarely appearing as if I had the slightest idea what I was doing.

My first real breakthrough came a couple weeks later, when, on a road trip to a family reunion in a small town in Vermont, I stopped in a music store and poked through its section of beginning guitar books. And it was there that I discovered David Mead’s Crash Course: Acoustic Guitar.

For the next seven days, Mead’s book became my bible; I worked through it exercise by exercise. Mead had no magic bullets; the contortions of the hand that the guitar required remained difficult, but his “crash course” broke guitar down into just the sort of bite-size morsels that an old owl like me could easily digest. It gave me a better sense of the basics of rhythm and helped me move beyond simple chords and isolated notes to grasp the significance of larger units, such as scales.

Scales are ascending (or descending) sets of notes that fit together naturally, conveying a particular mood or feel, such as the happy major scale or the sadder minor scale. The most famous scale is the C major scale, represented by the white notes on a piano keyboard: C, D, E, F, G, A, B, and back to C (think do-re-mi-fa-sol-la-ti-do). As I was to discover later, different scales elicit different moods, in part because of the different relationships between notes and in part because each scale has its own set of strong cultural associations with different scales. The song “Happy Birthday,” for example, is an arrangement of notes from the major scale, while the haunting melody of the Rolling Stones’ “Paint It Black” is an arrangement of a scale known as the harmonic minor.

Among the scales a beginner might learn, one of the simplest is the bluesy minor pentatonic, which consists of just five notes. The minor pentatonic, I soon found out, is a mainstay of rock and roll and the blues, used in countless guitar solos, from Jimi Hendrix’s “Hey Joe” to Dire Straits’ “Money for Nothing.” Soon it became a staple of my musical life—and a first hint that I might someday be able to make up my own music. Once I began to be comfortable with my first scales, my fumblings started to become faintly musical. My mother-in-law looked up. When she listened to my playing for the first time, even if it was only for a few seconds, I felt I was finally on to something.

Thus encouraged, I set aside all the books I was reading, stopped watching television, and devoted myself full-time to the pursuit of music. I committed myself to practicing every day, even buying a travel guitar so that I could keep practicing when I was on the road to give lectures, trundling it through train stations and airports from New Zealand to Abu Dhabi.

And loved every minute of it.

Learning about music soon became, for all intents and purposes, an addiction. Each new note, each new chord, each new scale, and each new rhythm brought me closer to something that I desperately longed for: the capacity to make my own music. Even basic observations like “the snare drum usually comes on the two and four” came as revelations. When I read some new neuroimaging studies that suggested that new knowledge can bring the same sort of surge of dopamine one might get by ingesting crack cocaine, I could only nod my head in agreement. Pressing plastic buttons in time with someone else’s song was one thing; creating my own music another, an adventure that seemed to bring me into a new place altogether: meditative, beautiful, intoxicating.

Along with all that beauty came something else: a first step in what was to be a long process of rewiring my own brain.

One of the first studies to examine the effects of musical practice on the brain came when a team of neuropsychologists led by the German neuroscientist Thomas Elbert combined an array of different brain-imaging techniques together in order to investigate what happens to the brain’s representation of fingers as a person learns to play an instrument.

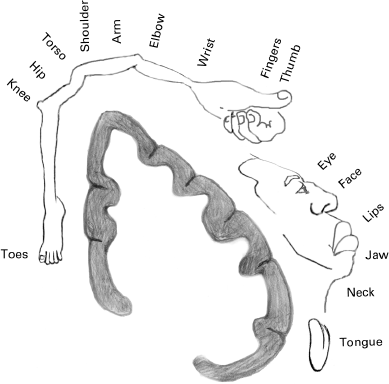

If you have taken a class in psychology or neuroscience, you may recall a famous picture that looks like this:*

The point of the illustration is twofold. First, the picture makes clear the fact that each part of the body has a specific piece of neural tissue assigned to it in the area of the brain known as the primary motor cortex; second, it also illustrates the fact that the exact amount of cortical real estate allocated varies from one body part to the next, with more sensitive areas getting more brain tissue. Fingers and lips get a lot, the back of the knee hardly any. (You can confirm this with the aid of a pin and a trusted friend. Close your eyes as the friend gently pokes you with the pin. In areas with heavy cortical representation, you will be able to easily discriminate closely spaced pinpricks; in areas with light cortical representation, you will sometimes be unable to distinguish two pinpricks that are close together but not identical.)

Earlier work by Michael Merzenich and others had shown that the boundaries between these areas aren’t entirely fixed; a monkey that lost its middle finger, for example, might reallocate some of the primary cortex that was assigned to its middle finger to an adjacent finger. Similarly, in people who are born congenitally blind, the brain sometimes winds up taking some of the neural tissue that would normally be used for vision and using it for hearing. Could music practice similarly rewire the brain?

Indeed it could. Focusing on nine string players (six cellists, two violinists, and a guitarist), Elbert and his team discovered that string players dedicated an unusually large amount of cortical representation to the fingers of their note-selecting left hands, likely yielding two benefits. First, it gives string players greater control of their fingers, and second, it may make them more sensitive to the feedback that their fingers receive, allowing them a more precise mental picture of where their fingers are, and even of how taut a given string is—vital for playing with the correct touch.

Since then, dozens of studies have furthered Elbert’s basic conclusion, that the brains of musicians differ from those of nonmusicians, and not just in the sensorimotor cortex but also in other brain areas such as the planum temporale (an area just behind the auditory cortex that is implicated in pitch perception), the cerebellum (implicated in rhythm), and the anterior (frontward) part of the corpus callosum, the thick set of fibers that connects the two sides of the brain, perhaps because of its role in coordinating the left and the right hands.

In keeping with these physical differences, the brains of musicians respond more sensitively to slight deviations in musically relevant parameters such as pitch, rhythm, and timbre (the sonic properties differentiating one instrument from the next, such as the sound of a violin versus the sound of a flute). The differences between musicians and nonmusicians depend in part on a musician’s instrument of choice; the brains of violinists are especially sensitive to the sounds of violins, and the brains of trumpeters appear to be specialized for trumpet. Opera singers show specializations in the part of the primary somatosensory cortex that represents vocal articulators and the larynx. (One can only wonder about Prince, who has been known to play guitar, keyboards, bass, drums, saxophone, and harmonica.)

These studies all raise an important question, especially salient for a beginner like me: Are musicians’ brains different because they are born that way or because of all the hours they put into practicing? With respect to initial differences (which could represent a physiological basis for what is colloquially known as talent), nobody yet knows for sure, but one recent study made it very clear that practice does indeed at least contribute to neural differences.

A team led by the Harvard neuroscientist Gottfried Schlaug tracked two groups of children for two years, starting at the age of five, half of whom were taking lessons in a musical instrument (piano or violin) and half of whom weren’t. At the outset, there were no apparent differences between the kids who took lessons and those who didn’t. Just fifteen months later, there were already clear neural changes: children who took lessons— especially those who had practiced extensively— showed greater growth in the brain regions that control hand movements, in the corpus callosum, and in a right primary auditory area known as Heschl’s gyrus. Practice might not make perfect, but it definitely has an effect on the brain.

Of course, evidence for practice is not evidence against inborn talent. Schlaug might have the best evidence for the importance of practice, but he still leaves room for talent, too. When I asked him about his own children, he didn’t hesitate. Practice matters, he said, but it was still important that each child find a musical instrument that was a good fit to his or her innate talents. In all likelihood, the brains of musicians differ from those of less musical counterparts for two reasons, not one: both practice and talent.

Brain studies have, of course, reflections in behavior. It’s not just that musicians have thicker corpora callosa; it’s that their brains are better at comprehending music, in processes such as detecting differences in pitch and slight variations in rhythm. In the brain-imaging study of five-to seven-year-olds, the magnitude of children’s brain changes correlated with the size of behavioral changes. In tests of motor skills and melodic and rhythmic discrimination, kids who took music lessons quickly overtook kids who didn’t, and the kids who showed the most improvement on these tasks were the ones whose brains changed the most.

All told, aspiring musicians must master at least three distinct sets of skills. They must develop their ears and brains so that they can recognize melodies (the basic tunes that serve as a song’s foreground) and harmonies (which serve as accompaniment). They must master time, tempo, and rhythm. And they must harmonize their muscles, coordinating their two hands together at a rate that on a piano can approach eighteen hundred notes in a minute (in complex chords, wherein every digit of both hands works full-time). The kicker is that ultimately all of these skills must be so well integrated that they can all be performed simultaneously, and continuously, throughout the course of any individual piece of music.

Engineers might call this taxonomy a task analysis; I’d call it a gigantic challenge. The sheer amount of brain rewiring that must be done is almost overwhelming. I wished desperately that there were shortcuts to all that neural rewiring, but as a cognitive psychologist I knew better. Playing smoothly would entail rewiring my whole brain, from my temporal lobes to my prefrontal cortex, and there was no way around that. It was time to get cracking.

* As I was to learn later, some guitarists extend the definition of chords to include certain pairs of notes, such as the “power chords” (see glossary), neither major nor minor but somewhere in between, that give rock and heavy metal their aggressive feel.

* The careful reader will note the absence of genitals in this G-rated version of the sensorimotor cortex. Luckily for the reproduction of our species, the genitals receive considerable coverage in the neural representation of haptic space.