It was about three o’clock in the afternoon when the hearse ran away.

This was one of Singapore’s very hot days, when the heat sat in thick layers upon the dust of the streets and people moved as slowly as they could so as not to attract its attention. The hearse, one of the newer auto models, had been moving slowly. One moment it was trundling demurely along in the funeral procession, puffing gently; the next, it was shrieking down Victoria Street trailing clouds of steam and bruised mourners in its wake. A yawning fissure in the road skewed it a sharp left, and it ploughed through streets of terrified carpet merchants and songkok makers. Nobody tried to stop it, of course; any engine on wheels was liable to explode these days, and hearses were particularly contentious since the health of their passengers was no longer a standing issue. Instead, the runaway hearse went on gaining speed and losing pursuit, shedding flowers and tassels, until it crashed to a stop in the Malay cemetery.

By the time the funeral party caught up, the hearse was lying on its side, gaping, empty. The mourners looked to their leader, who swore violently in Cantonese, paused for breath and added, “It can’t have gone far.”

“No,” said another, “it’s a body.”

Still panting, their leader surveyed the wreckage of the hearse, the gathering crowd, the growing unease that traditionally followed the incursion of large groups of Chinese men into a Malay neighbourhood. How long did they have before the police showed up and started asking difficult questions? He weighed his options.

The hearse solved this dilemma for him by emitting an ominous whistling noise, and then blowing up.

The ensuing chaos meant that nobody noticed when, a few streets away, a door flew open, a dish smashed and a woman screamed.

~*~

“Weapons,” said the man at the door.

Ning Lam raised an eyebrow. She pushed her loose braid back over her shoulder, reached inside her paper cone of kacang puteh and popped a boiled chickpea into her mouth. This she chewed deliberately.

“Weapons,” growled the guard again. “You’re not going in to see the old man armed to the teeth. And throw away that stupid snack.”

Ning rolled her one good eye. The other merely clicked in her head, a gleaming clockwork eyeball, and remained pointing straight at the guard, a trick that most found disconcerting. Indeed, the man almost flinched, only just catching himself. Ning winked at him with the good eye, unclipped her butterfly knives from her belt and laid them on the table, followed by two boxes of bolts. From her back, she unstrapped her crossbow. ‘This I’m keeping,’ she added, waving the kacang puteh.

The man made an ill-advised grab for it. Ning tossed the paper cone to her left hand; with her right, she grabbed the oncoming fingers and twisted them halfway around. The man let out a yelp. Ning released him and strode past, fishing in the cone for roasted nuts.

She heard him spit in the doorway after her retreating back. “Fucking hybrid.”

Ning made her way across the gambling floor, past yelling men in singlets jostling elbows with bored housewives at the chap ji kee tables and the brassy new slot machines. The room beyond was dim and low-ceilinged; she had to stoop as she picked her way across the mess of thin copper pipes that snaked across the floor and curled up besides the shadowy figures lying prostrate on low bunks, sucking dreamily at the opium smoke flowering from the gutta-percha mouths of the pipes. Down another corridor, another man standing guard at the end. This one asked no questions, merely looked her up and down in her coolie trousers and her dirty kebaya that was once a light green, now loose and unbuttoned over a samfoo top. He held back the red beaded curtain for her to step through, saying as he did, “Miss Ning, Grandfather.”

“You are early, Miss Ning,” said the head of the kongsi. “If you will excuse me my unfinished business, I will be with you in a moment.”

He turned back to the table he was examining. On the table lay a carved tray carrying thirty or so fingers. Some of the fingers had gold rings on them and some had long scars. None was from the same hand. Ning popped kacang puteh into her mouth, discovered it was a dried pea and spat it out.

“Make sure you wrap them nicely before they go to Penang,” Grandfather said to the waiting men. “I want the Hakka scum who fester there to be able to tell which is whose. Let them think twice before they interfere with our shipments again. Not that one,” he added, pointing at a finger in the corner which had had its nail gnawed something dreadful. “That one is from Eng Siok, whom I once thought of as a son. Send it to his family in Keong Saik, to show them he has spit on our sacred oaths. Perhaps it will help them remember to whom their allegiance is owed.”

The tray of fingers was whisked away, replaced by two cups of steaming tea. “Forgive me the display, Miss Ning,” said Grandfather. “It is distasteful. I am but a humble businessman, trying to help my people get by. Unfortunately this makes me enemies, and they have—shall I say—forced my hand.”

Ning crumpled up the empty paper cone and sat down. “Longjing,” she remarked of the tea. “You honour me, Grandfather.”

“I have it shipped straight from Zhejiang,” replied Grandfather. “You have a good nose for teas, Miss Ning.”

“I have a good nose for many things.” Ning picked up the teacup, passed it delicately back and forth beneath her nose.

“So we hear.” Grandfather did the same. “We have need of such a skill now. There is a missing woman. Chinese, tall, heavily scarred about the body; you’ll know her when you see her. She was last seen near Kandahar Street.”

“Ah,” said Ning. That explained some things. She was fluent in Malay and familiar with the Kampong Glam area; few in the kongsi could lay claim to either. “That hearse business, that was your doing.”

Grandfather raised an eyebrow. “Quick of you, Miss Ning. Yes. The hearse was ours.”

“Now I don’t pretend to be an expert on hearses,” went on Ning, “but usually the folk inside them, they’re dead.”

“Shut your mouth!” came a voice from the back of the room. “No more of your lip to Grandfather, hybrid.”

Ning glanced at the man hunched in the shadows. Chee the Younger, Grandfather’s great-nephew, slouched on a stool picking his nails with a pocketknife. “Someone’s touchy,” she mused. “Let me guess. The hearse was your idea. Takes a genius brain like yours to balls up an errand that simple. But what do I know, I’m just a simple working girl.”

Chee leapt off his stool, came into the light. “Grandfather, I’ve said it already, there’s no need to bring in outsiders on our business, let alone a half-woman with no clan to her name, I said—”

Grandfather slammed his fist down on the table. The teacups sloshed. “You’ve said enough, is what you’ve said! I’ve lost enough men on this fool’s venture.” He sighed heavily. “Bringing all these machines into the business. It’ll be the downfall of us all. In the old days you threw an axe at a white man and he went away. None of this mechanical devil-shit.”

Ning sipped her tea and did not point out that throwing the axe at the British head of the Chinese Protectorate had indirectly resulted in the violent crackdown on the Chinese secret societies, under which business had suffered since. Eventually Grandfather continued. “The woman you are to look for is not…all flesh.”

“A hybrid, then.”

“So to speak.” Grandfather paused, then added, “More hybrid, in fact, than anyone you will ever have seen.”

“Where’d you take her from?”

“None of your business,” growled Chee.

“It is my business,” retorted Ning, “because whoever that was, they’re going to want her back. And I need to know if they’ll get in my way.”

Grandfather said, “She was government property.”

Ning whistled. “Cheeky. You know I charge extra for tangling with British.”

“You’ll be paid for your time,” snapped Grandfather. “And for your discretion. If you are compromised, nothing is to come back to us.”

“What do you want her for, anyway?” Ning demanded. “If she’s got that much gear in her, there’s not a decent engineer in Chinatown who’ll know how to sort out her insides.”

“Now that,” said Grandfather, “is none of your business. Deliver her, that’s all you’re to do.”

Ning held her tongue. It was not hard to envision what the kongsi might want with a top-secret government experiment. The British crackdown had significantly crippled their activity; they were still searching for ways to hit back. Even if they didn’t know what to do with their prize, holding it ransom would deal enough of a blow to the government.

“We’ll expect to hear from you daily,” Grandfather went on. “I like to know what I’m paying for. And I don’t enjoy being kept waiting.”

He traced idly with his finger a pattern in the table’s wood where years of scrubbing had evidently failed to remove the bloodstains from the grain. “Naturally,” said Ning. “I am very prompt.”

“I should hope so,” said Grandfather. “Bring the woman. You’ll get your money then.”

“I’ll need some advance,” pointed out Ning. “Information costs.”

Grandfather paused, then motioned irritably. Chee came forward grudgingly with an envelope, which he dropped on the table before her.

“She likes the feel of money, I bet,” he sneered. “Of course, a girl who’s been sold for silver would know about that kind of thing.”

Ning said nothing. Grandfather coughed and said, “Thank you for your time, Miss Ning. We’ll be hearing from you.”

Ning said, “Thank you for the tea,” picked up the envelope and walked out. She walked past the dreaming smokers, through the hot noise of the gambling room, out into a street full of early monsoon rain.

~*~

Khairunnisa ran downstairs. She locked and barred the shop door. She did the same to the back door in the kitchen. She drew all the curtains.

There was a crash upstairs. Khairunnisa paused, then made herself turn and climb the stairs.

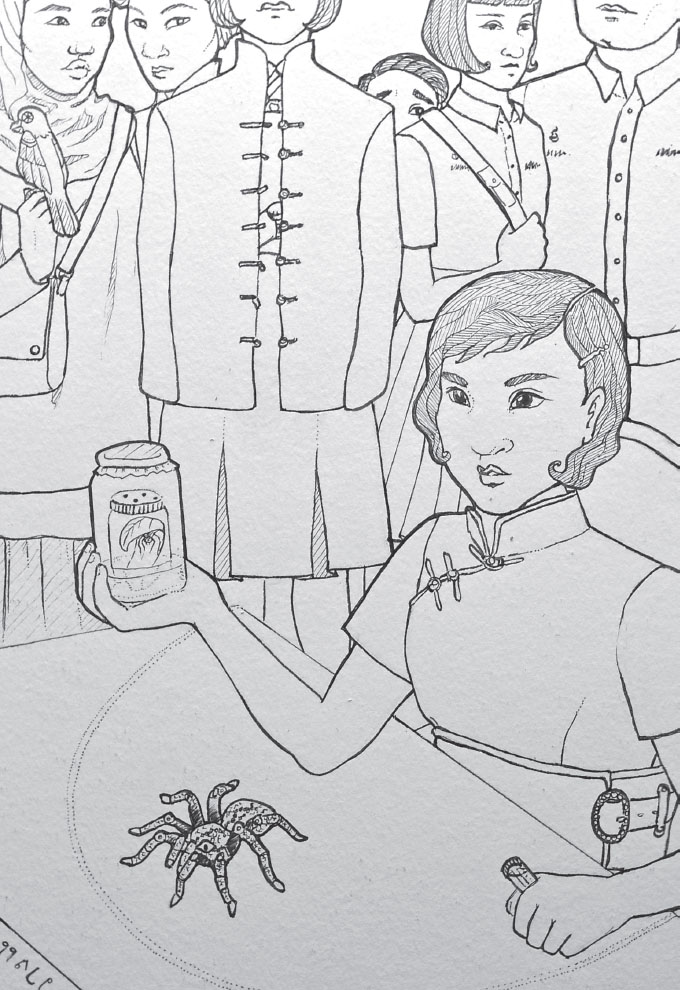

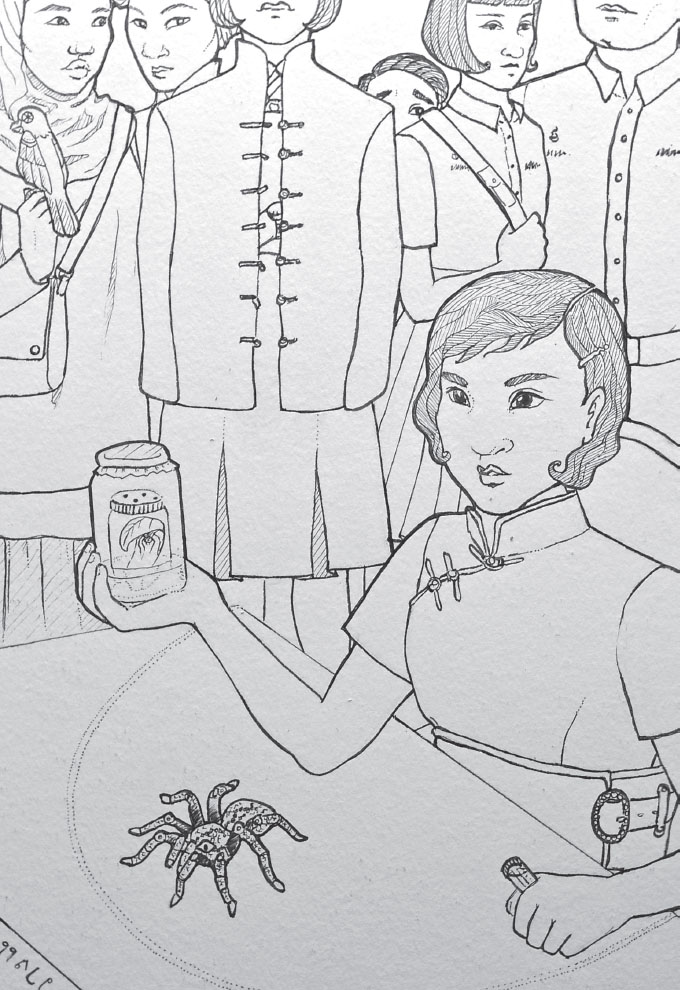

Khairunnisa’s life had not been very exciting since the event of her widowing. Nor had it been before that, but at least having a husband to talk to from time to time made things less monotonous, even if they had not quite succeeded in transcending social awkwardness in the one and a half years of their arranged marriage. This was punctuated by two surprises: first, when an ornihopter fell out of the sky in Batavia and hit, of all people, her husband trying to cross the street to a toy convention; second, when he left her the house and the toy shop in his will despite the simmering unhappiness of his family and hers. Still, she had been better at it than he had ever been. She made beautiful things, and they always worked. So she shut herself up in the workshop while people talked, about her living alone and running her husband’s business without a thought for his family; she made it so she could not hear them over the whirring of the gears and the tinkling of the music boxes. And the children loved what she made, and people would come from the ends of the island to Bussorah Street for her clockwork Javanese dancers and wayang singers, her tiny motorcars and rickshaw robots, her intricate mobile of glittering tin dirigibles floating lazily in circles on an engine she promised would last three years on guarantee. And it had been all very nice and calm, until a crazy Chinese woman had come in through her back door, covered in blood and raving in a language she could not understand.

The woman was thrashing in the corner of the workshop where Khairunnisa had left her. “No, please be still,” begged Khairunnisa, “someone will hear, I don’t think you’re even supposed to be here.” The woman stared at her, not understanding. She was immense, Khairunnisa realized, hulking shoulders, had to be nearly two metres tall. She wore odd clothes, dark blue and ill-fitting, torn in places through which Khairunnisa glimpsed scars lying thick on her flesh. She began shouting in what was definitely not Malay, but did not sound like Chinese either. Against all odds, it sounded like English.

Khairunnisa tried to make hand gestures to be quiet, which seemed to work until she realized the woman had been pacified not by her hands but by the sight of the Javanese dancer on the workbench, slowly articulating its feet in neat patterns, gently wobbling its elaborate gold foil headdress. “You like that?” said Khairunnisa, relieved. “I have lots. Here, look!” She wound up more dancers, which moved their arms and flexed delicate, shining fingers in uncanny synchrony. The woman was fascinated at first, but then her face clenched and she started to shudder. Her own fingers twitched in something like horror and she began to mutter, to point at Khairunnisa and the dancers and to claw at her own throat. “Please, what do you want,” begged Khairunnisa, “I can’t understand you, I can’t—”

The back of the woman’s neck had begun to run blood again. There was a nasty open wound on the back of her head, which Khairunnisa could not bring herself to look at. But now she glimpsed something flashing inside the pulped flesh, heard a familiar whirr and click beneath the incomprehensible cries. “Shhh,” she said, approaching slowly, trying to get behind the woman without her noticing. She had to stand on tiptoe to reach the wound. “Shhh,” she said again, and the woman made a confused expression halfway between a smile and a wince, as Khairunnisa reached deftly inside the wound, found what she knew had been there all along and pulled it, hard.

The woman collapsed onto her, heavy, something she had not been expecting. Blood pumped from the wound onto Khairunnisa’s face. She was looking up, into the intricate mess of wheels and discs inside the woman’s head, nestled tightly within her living flesh. Khairunnisa thought briefly of her dolls. But this was so much more.

~*~

The smell of food awakened her. Someone was in the room, singing softly, snatches of some song about an old bird. She forced her eyes open and saw the singing woman crouched at a low table, laying out dishes.

“You’re awake!” The woman put the food down and came over to her; she flinched, and the woman paused, then got down on her knees and put out her hand tentatively. After a while she allowed the woman to edge closer, touch her face, feel the back of her neck. “Is there pain? Can you hear me?”

“No,” she heard herself say. “No pain.”

“I reconfigured the language punch-cards in your head.” The words made no sense. “I didn’t understand anything you wanted, I was worried. Your punch-card was in English for some reason, but luckily I had a Malay sample I was trying out on some of the dolls. It’s not very developed, there are lots of things you still won’t understand.”

“There’s something else I should be speaking. Some other tongue.”

The other woman looked away sadly. “Chinese, yes. Or your home dialect. I don’t know. It was overwritten when they programmed you, I think. I’m sorry.”

Overwritten?

“My name is Khairunnisa,” continued the other, rising and moving over to the table. “Or Nisa, if you want. Yours?”

She shook her head. “Don’t know.”

“I feared so.” Khairunnisa knelt by the table and beckoned. “I got us some food from the padang stall. Lucky they were still open. I thought you might be hungry, you slept so long after I fixed your head.”

Nothing made sense still, but the food smelled better than anything she could remember eating. Not that she could remember eating, or remember anything. Khairunnisa pointed out chicken rendang, jackfruit curry, vegetables in coconut milk. Uncertain, she tried to copy Khairunnisa eating expertly with her right hand.

“You don’t remember where you came from? Who you are?”

She thought hard, trying to get a grip on a slithery chunk of unripe jackfruit. “I was in a box. Moving. I was trying to get out.”

“A hearse crashed into the cemetery near here,” said Khairunnisa. “I think you were in it. But why they were taking you to be buried I don’t know. You’re not dead. You can’t…I don’t think you would die in the normal way.”

“I’m like them.” She pointed at the clockwork toys that watched them eat from the bench. “Inside.”

“No,” said Khairunnisa. “You’re better than them. You’re better than anything I’ve ever seen. I don’t know, of course, I haven’t really looked inside you. But you’re talking to me. You’re eating my food. I don’t know if you’re a living person whose inside has been entirely replaced by clockwork organs, or if you’re a machine who somehow does living people things. Or both. It’s incredible. Have you tried the sayur lodeh?”

“You knew how to fix me.”

Khairunnisa shrugged. “It was simpler than I thought. These things make sense to me—more than words, or numbers, or cooking—gears always speak the same language.”

“If I sleep tonight will you fix me again?”

“Do you want me to?”

She thought about it. “If somebody has to open me up, better it’s you. But I don’t like it.”

“Then I won’t fix you unless I have to,” said Khairunnisa, getting up. “I’ll have to open your sternum to load some coal in, but that won’t be for a while, and anyway I can teach you so you can do it yourself.”

“Thank you,” she said. “Thank you, Nisa. For this.”

Khairunnisa laughed lightly. “It’s nothing. You can sleep in here. I’ll get a mat.”

She waited alone before the food-stained dishes and the silent toys. A bottle of red saga seeds on the windowsill kept catching her eye. The colour reminded her of something, she just could not think what.

~*~

Ning did not enjoy speaking Malay. She had been forced to learn Baba Malay during her years of bondage in a Peranakan house; it had been over a decade since, but the sound of it still left the taste of beatings in her mouth. However, the language was now part of her stock-in-trade, and here in Kampong Glam she chatted up perfume-sellers, shisha smokers, anyone who might have seen a six-foot-tall Chinese woman with scars running around after the hearse crash. People were hesitant towards this uncanny woman with one eye, for all she might joke about in their tongue, but Ning was known to some and charming to others, and above all assured money under the counter for the good stuff. The old men at the teashop had maybe seen one such woman heading for Bussorah Street, though as they had been afternoon-sleepy they could not say which household she had graced. The owner of the Sufi bookstore on Bussorah allowed that perhaps some screaming had been heard from the shophouse of the late toymaker Al-Jazari, may Allah rest his soul in peace. A sweeper at the nasi padang stall on the corner recalled the widow Al-Jazari making a late-night trip to their premises to buy food for two. “But what to expect, her living alone like that?” she lamented to Ning. “Bound to be trouble sooner or later. You know what I mean?”

Ning watched the toy shop, waited till dusk when she would be less visible, and then did a little climbing until she sat straddling the roof of the Al-Jazari domicile. Delicately, she reached up and pushed two fingertips into her right eye, her fingernails found the faint grooves in the glassy surface above the irises. With a pop, the eye came loose from her head.

From her waist pouch, Ning pulled a device that seemed to be composed of multiple tiny abaci. The first two rows she deftly manipulated with a hairpin; this set the rest of the wooden beads snapping into motion of their own accord. With the same hairpin, she pried open a panel on the bottom of the eyeball and flipped a few minuscule levers, then replaced the panel and dropped the eye in the roof gutter.

The eye began to roll. It rolled along the gutter and dropped down onto the parapet below, where it swivelled rapidly to regain its balance. From there it rolled on industriously out of sight.

Ning got off the roof and went round the corner to the drinks stall, where she sat drinking black coffee for an hour.

Then she strolled back to a grassy patch near the Al-Jazari house, where the eye lay, slightly grimy.

Ning polished it on her blouse. Then she sat down, braced her back against a tree for good measure, and pushed the eye back into its socket.

The kickback nearly floored her. Her back arched from the shock of it, as volleys of images jittered through her brain, an hour’s memory registered in a second. Ning tried to ignore the resultant headache, piecing together what the eye had seen on its reconnaissance.

“Oh yes,” she said aloud, to the eyeball if nobody else. “That’s the house.”

~*~

The women get up at four in the morning to walk to the fields. The road is not well-made, but their feet are hard and they no longer feel it when the cracks bleed. When the sun rises, they are already hauling rock, shovelling coal, watching the great machines as they hiss and pummel the earth and vent columns of steam into the grey, humid dawn.

These are the dirigible fields of Changi. Vaster yet than anything the island has raised from its virgin swamps. Every day they call for more workers, more hands, and the fields seethe with blackened figures roaring work commands in half a dozen dialects. Among these masses, the women always know each other by the red headdresses they wear, bobbing brightly here and there across the treacherous walkways like saga seeds in the mud.

The oldest among them is well over fifty, the youngest just shy of her sixteenth birthday. Still unused to balancing her yoke while navigating the flimsy walkways, she stumbles sometimes, little Chai Sum, and the others watch her like hawks because if one falls, they all fall.

They only stop once, at mid-day, when the sun beats down so hot it seems to blister the very soot flakes as they cloud the thick air. Over their lunches of rice and pickles, they chat—about home, mostly, about the seven younger siblings Yip Soh left in her village, who she needs to send money to this week. About the unreliability of men: Man Lai, as usual, bares her bicep to show the burn scars from where her husband struck her with a boiling kettle, after which she fought her way onto a slow boat for the Straits of Malacca and never looked back. About the machines, how they get bigger every day, how they eat more coal. “If they keep bringing more in we’ll be out of a job,” grumbles Cheuk San. Yuk Hong, the tallest and broadest among them at over six feet, laughs. “They’ll never get in machines that work faster or better than us. They’ll have to keep paying us for all the crap they need done.” Ah Lei, the oldest and their de facto leader, does not laugh with the rest of them. “I don’t trust them, those machines. I hear they had an accident in Field Five the other day. Valve blew on a pumping engine. The men on the platform with it, their own mothers couldn’t recognize them now if they brought them over from the old country to sort the bits that are left.”

The women finish their meals, fill their bowls with water and slurp them clean so that they don’t leave a single grain uneaten in the bowl. They tighten the straps on their sandals, patched together from old car tyres, and head back to work. Today they are carrying coal to one of the giant drilling rigs, which makes a racket so deafening the women cannot talk; instead they follow Ah Lei’s quick hand signals with the ease of long practice.

It’s Cheuk San who sees the leak first. The engineers on the rig have not spotted it yet; they do not hear her shout. Ah Lei senses something is off; the women all down the line see her mouth open in a silent scream, see her slide the yoke from her shoulders and turn to run. What they do hear is the sound, the unmistakeable rumbling thunder, that seems to pour forth from her mouth and through their heads and into the hot, still air above them.

And then everything goes white.

~*~

She woke with a start to Khairunnisa shaking her. “You were crying. Bad dream?”

“In the dream,” she said slowly, “we are speaking. We are speaking but the words are lost to me.”

“You don’t know what they’re saying?’ murmured Khairunnisa.

“I know what they mean. I don’t know how they said it. The language—it’s gone.”

She rolled up her sleeve. There, the burn mark. She had known all along, in the incongruous moles and birthmarks, in her impossible height, in the scars that mapped her body in the uneasy badlands between memory and skin. And the memories, the memories, of her sisters skipping in the yard and the sun in the mountains and early rheumatism and weak rice and the sounds she made when the boiling kettle seared her skin. Of the ocean. Different boats, same ocean. The dozen moments she set foot on Singapore for the first time. She knew what she was.

She began to moan, rocking back and forth. “What, what,” begged Khairunnisa, trying to hush her before someone heard. She could not tell her; knew if she told that Khairunnisa would not want to fix her any more, would not lay a finger on her ever again. She wanted to tear her limbs from her shoulders, hands from wrists, heart from steam chamber, to put everything back in the charnel heap from whence it came. Somewhere out in the night, the rest of her lay festering, unburied. The ashes never to be sent back to the dozen villages she knew as home. And this body, this abominable patchwork of flesh and metal that should never have been. She dragged her fingernails down her collaged face and screamed. Khairunnisa bit her nails and did not know what to say.

~*~

Ning waited till all the lights in the house had gone out again. Then she scaled the drainpipe again and deftly unlatched the workshop window using a hairpin.

It was dark in the workshop. Ning trod carefully, but the floor betrayed her with a drawn-out creak.

Something moved, rose, silhouetted against the window. Ning stayed still. The sound of a match striking, then the flare of a candle.

A huge woman was staring at her. Her face odd, something off about it, like someone had described it to an artist who had never seen a woman before. Ning knew this was the woman she wanted. She levelled her crossbow at her.

“Easy now,” she said. “We’re just going to take a little walk.”

The woman moved towards her.

“This is a crossbow,” hissed Ning. “I will shoot you!” A lie: the kongsi would not pay for a dead woman. “Oh, for—”

The woman slapped the crossbow away. Ning turned to dive out of the window again, but the woman hauled her back. Then she punched Ning in the face. Stunned, Ning watched the world turn upside-down and bloom into agony.

~*~

This is the dream from before she was Ning. Ah Mui is the name they call her in the dream.

Ah Mui thinks she should leave. She should leave the house now, because she has scratched the tempat sireh. The bibik has said before that if Ah Mui ruins any more of her things, she will beat her to death. And the tempat sireh, with its delicate gold leaf, is a favourite of the bibik, who likes to have her friends admire it while they chew betel until their mouths are red as if they have drunk blood.

Ah Mui thinks she should leave, but where will she go? She has never been outside the house, from as long as she remembers. She has barely even been allowed upstairs. And now the bibik is coming, she is coming down into the kitchen, calling for Ah Mui. From where she is hiding in the woodpile, Ah Mui sees her feet first, in their beaded slippers, then the print of her sarong, then her beautiful kebaya. The bibik has seen the scratched tempat sireh. She stops in the middle of the kitchen. Then she begins to shriek and overturn the kitchen to look for Ah Mui. The kitchen is not large. Ah Mui is dragged sobbing from the woodpile and the bibik begins to slap her, crying stupid girl, bastard girl, I’ll kill you. I’ll kill you and nobody will notice. You are not anything to anyone. Your parents sold you for money. Even then they charged too much and I should have got you for cheaper because you are not worth the food I have to feed you, you get nothing right.

Ah Mui is trying to curl up, to hide her face with her arms. The bibik pulls her hair to force her head up. Ah Mui sees herself reflected in the polished sides of the stove, the bruises rising to her skin, the tears leaking from both her eyes. Then the bibik smashes the right side of her face into the corner of the table, over and over. Pestle and mortar. When she comes back up, Ah Mui can no longer see anything of herself. There is nothing left to see.

~*~

Ning swam in and out of consciousness, hovering above the horror of the old memory. Someone was talking. A young woman in Malay.

“…this is incredible. It’s European make, I think, but there have been so many modifications it’s hard to tell what it used to be—the lensing is marvellous, you don’t get that sort of work anywhere off the black market. Where on earth you would get something like this—”

“I got if off a Bugis pirate,” mumbled Ning. She was sitting down, she realized, tied to a chair. Her head felt like it had been mined for tin ore. “He couldn’t pay me, but luckily for him I’d taken a liking to his eye. Most of the extra work I got done by a watchmaker in Geylang. I could give you his address, if you liked.”

The Malay woman—Khairunnisa Al-Jazari, if she wasn’t wrong—was staring at her open-mouthed. She seized Ning’s crossbow and aimed it at her. “Tell us who sent you!”

“You don’t even know how to take off the safety catch,” said Ning. She tried her hands, but they were well and truly bound behind the chair.

The other woman rose from where she had been squatting in a corner. She was truly immense. Closing her fingers around Ning’s throat, she rasped, “Who sent you?”

“The people who stole you,” Ning choked out. “Surely that’s obvious.”

From the expression on both their faces, neither woman had any idea who that was. Ning attempted to change the conversation. “How come you speak Malay?”

“So? You speak Malay,” pointed out the tall woman.

“I am gifted beyond your wildest dreams,” said Ning. “But I’m guessing you picked it up even quicker than me, no?”

Both of them ignored her. “What do they want her for?” demanded Khairunnisa.

“I actually have no idea,” said Ning. “I’m just the delivery girl, right? I hand you over. They pay me. Nobody needs to lose any eyeballs. Speaking of which, can I have mine back now?”

“No,” snapped Khairunnisa, hiding the eyeball somewhere in her sleeve.

“Oh well,” said Ning. “You should let me take her, you know. Not one, but two surprise Chinese women appearing in your house. Headache, I tell you.”

This earned her a slap from the tall one. Ning’s head rang with it like a bell.

“We’re doing this the wrong way,” Ning went on blithely, ignoring the risk of being throttled. “Let’s be nice. Hello, my name’s Ning Lam. What’s yours?”

The other stared at her a moment, then walked off brusquely. She returned holding one of the dolls, a Chinese bride in scarlet robes. “You speak the language I’m meant to speak, yes?”

“Chinese?” hazarded Ning. “Cantonese? Probably.”

The woman pointed at the doll’s garments. “What colour is this? In that language.”

“Red? Um—hong, I suppose—”

“Right then. That’s what I want to be called.”

“That’s nice,” said Ning. “Hong. Ah Hong. Nice to meet you. You too, Khairunnisa. We’re going to get along so well.”

“There’ll be more like her coming,” said Ah Hong to Khairunnisa. “We ought to kill her. I can carry the body, easy.”

“Oh for your mother’s sake,” muttered Ning.

“I would really rather not kill anybody,” whispered Khairunnisa.

“Me too,” added Ning. “I wasn’t going to kill anyone to begin with. I was just going to bring you to these nice people, they don’t want you really, they just want to have you so that the British or whoever made you get mad.”

“Look me in the eye,” said Khairunnisa. “Look me in the eye and tell me they won’t hurt her.”

Ning tried to hold her gaze. “Well—”

Khairunnisa turned away coldly. Ah Hong said, “I won’t be given away. I won’t be taken apart like a dead thing. I won’t be bought and I won’t be sold. You don’t know what that’s like.”

Ning was silent for a while. Then she said, quietly, “You’d be surprised.”

Ah Hong squatted in front of her, till she was almost nose to nose with Ning. “If you had even the slightest idea, then you wouldn’t be about to do it to someone else.”

Ning said nothing.

There was a knock on the door.

“Don’t open that,” said Ning, instinctively.

Khairunnisa hesitated. “Maybe… one of the neighbors…”

“At this hour?’

“I’ll just go see…” The knock came again. Khairunnisa headed for the stairs. “Don’t make any sound.”

She was at the foot of the stairs when the door crashed open.

“Untie me,” hissed Ning. “Untie me now.” Ah Hong stared at her, wordless with panic.

From downstairs Khairunnisa screamed. “I have to—” gasped Ah Hong, starting for the door. Khairunnisa’s scream was cut short. Ah Hong froze as footsteps sounded on the stairs.

Ning began, without subterfuge, to scratch at the rope with the tiny blade hidden in her fake jade ring.

A man came through the door. A Gurkha, judging from his uniform and the curved Kukri blade he held lightly before him. “Number 24,” he said in English.

Ah Hong had begun to shake. “No,” she said. It was the first time Ning had heard her speak English. “You will not call me that.”

“Number 24,” repeated the Gurkha, “everything is fine. I’m taking you home.”

“Where’s Nisa?”

“She’s fine,” said the Gurkha. “She’s just unconscious. We want her alive too.”

Ah Hong howled. Lowering her head, she charged the Gurkha. She was at least two heads taller, but the Gurkha did not flinch. Moving fast—faster than anyone Ning had ever seen—he slid out of Ah Hong’s path and dropped her with a blow to the back of her knee with his kukri handle. As she stumbled, he was suddenly behind her; with a flash of his blade he opened a huge gash at the back of her head before she could grab for him. Ah Hong screamed. Grabbing her in an expert armlock, the Gurkha reached inside her head, feeling about, and ripped something out.

“No,” gasped Ah Hong, “n-n-n-n-n-n—” She crumpled face-first into the ground.

The Gurkha ignored Ning and called a command down the stairs. Two other men entered nervously and carried Ah Hong’s body out. The Gurkha walked over to Ning and calmly removed the ring from her finger.

“I know who you are,” he said simply. “You’re like me. The hired help.”

“I expect I’m paid a damn sight better than you,” snarled Ning.

“It’s not about the money. And you won’t be paid this time.” The Gurkha leaned over her. “Take this message from my master to yours. Don’t come for her again. We know how they did it. We know who they are. There will be blood. You understand?”

Ning bit his ear.

The Gurkha yelled in pain and backhanded Ning so hard she flew across the room into Khairunnisa’s workbench. The chair legs snapped under her. Teeth buried in her lip, Ning scrabbled behind her till she felt a file in her fingers.

The Gurkha came on, his kukri a blur. Ning barely ducked the first blow and rolled under the bench, the remnants of the chair crunching. The file clenched between bleeding fingers, she scraped furiously. Little clockwork dancers went flying as the Gurkha upended the bench to get at her. She felt the last strand give just as his blade caught her in the thigh. Ning hissed, tore herself free of the chair and sprang for her crossbow, lying in the debris of the bench.

The Gurkha only just eluded the first volley of bolts by diving to the ground. Ning rocked up and fired again as he scrambled for the door. Lights came on in the neighbouring windows, and people were shouting.

The Gurkha made it down the stairs, Ning storming after him, and leapt into the waiting motorcar at Khairunnisa’s door. It clattered off down the street and out of sight before she even cleared the threshold.

Ning swore profusely in Hokkien, the dialect she favoured for profanity. Then, as the neighbours started flooding into the street to see what was happening, she too had to slip away.

~*~

“Extraordinary,” said Dr. Horace Bradford. “Simply extraordinary. You’re quite sure it was her?”

“Her alone, sir,” replied the Gurkha. “I was watching the house. They had no visitors till the Chinese agent. When I entered to retrieve 24, it had been reactivated and was speaking Malay.”

They were in Bradford’s laboratory, staring down at the prone form of Khairunnisa on one of the operating tables.

“But such work from a native,” marveled Bradford. “And a slip of a girl, at that.” He removed his goggles and began to polish them absent-mindedly with a fistful of his coat. “Why, I doubt my so-called colleagues in Bencoolen could get 24 to even twitch a finger. We’ll have to keep her around, this girl, see what makes her tick.”

“Her disappearance will have raised some alarm,” said the Gurkha. “I fear that in retrieving them I was… indiscreet.”

“Ah, someone will take care of it, I’m sure,” muttered Bradford. “A pity you had to disable 24 though, Narayan, I’ll have to cobble together its spinal cord all over again.”

“Apologies, sir.”

“Astonishingly tenacious though,” went on Bradford, “the bodies of these, er, samsui women.” He had turned to where Ah Hong lay in shambles on another table, peering into her various ruptures. “I must say, they are eminently suited as subjects. We’ll have to put in an order for some more.”

Khairunnisa had begun to stir. As she took in her surroundings, she let out a whimper.

“The girl’s awake.” Bradford donned his goggles and advanced upon Khairunnisa, who flinched from him and began to call desperately for Ah Hong. “Have you a clue what she’s saying, Narayan? I haven’t the faintest.”

“I believe it’s the name she has for 24, sir.”

“How quaint,” said Bradford, trying to keep Khairunnisa pinned to the table. “Women have such funny ways. I say, my dear, would you keep still a moment? Narayan, do give us a hand.”

A bell started to ring. The Gurkha went over to the speaking tube on the laboratory wall. “Yes?” After a while, he said, “Sir, somebody to see you.”

“I have no appointments,” snapped Bradford, as Khairunnisa toppled off the table and scrambled behind a cabinet. “Tell them I’m indisposed.”

“It’s Mr. Stroud and Mr. Murchison, sir.”

“Well, that’s bloody tedious of them.” Bradford fumbled irritably with his goggles and leather apron. “See that you lock her in.”

They left, the Gurkha bolting the door after them. After a while, Khairunnisa crept out from behind the cabinet.

She tried the door first, but of course it would not give. Then she checked the lifeless Ah Hong, running shivering fingers over the ruin of her. She cast her eyes around the laboratory, and froze.

There were other bodies. Lying on slabs or in glass drawers, stacked on top of one another. Some of them, like Ah Hong, had machinery worked into them. Some were in pieces.

Khairunnisa turned to look at the cabinet she had taken refuge behind. When she opened it, it gave off an icy gust. Inside, packed in ice like cuts of meat, were body parts sorted neatly in rows. Arms, thighs, livers, tubes.

Khairunnisa fell back against the table. Her trembling hand brushed against Ah Hong’s limp one. Slowly, unwillingly, her eyes moved from the cabinet of flesh to the scars on Ah Hong’s body, multitudinous. To the odd discolorations of her skin. Khairunnisa clapped her hand to her mouth and was sick on the laboratory’s smooth white tiles.

~*~

Ning limped stubbornly through the night. Her lip was split; her trouser leg was stiff with blood. Occasionally she pulled out the abacus device and checked it, before hobbling on. When she passed under gas-lamps, her eye socket gaped harsh and empty.

~*~

It was a warm night. The black-and-white blinds in Bradford’s living room had been raised to admit the weak breeze, along with the flying ants and tiny night moths that lived in the bungalow gardens. Stroud and Murchison, despite the heat, had not shed their coats.

“I do apologize, gentlemen,” Bradford was saying with obvious discomfort, “I’d offer you refreshments, but you see the servants have gone for the night… this is quite unexpected…”

“So were your recent escapades,” responded Stroud.

“But that’s all sorted,” Bradford hastened to add, “the subject’s been retrieved, you know…”

“An explosion in the Malay cemetery.” Murchison wore strapped over his coat a slim aether tank, the nozzle propped on the arm of Bradford’s chaise longue. Bradford’s eyes kept flicking anxiously to it. “A midnight house raid. Neighbors’ complaints. Police reports. And on top of that, the secret societies nipping at our heels. I would be worried, old boy, really I would.”

“We give you top-notch equipment,” went on Stroud. “Fresh supplies. Your own personal guard. And you’re still letting the side down.”

“I beg your pardon,” exclaimed Bradford, “the project’s really making unprecedented leaps—why, 24 is fully integrated and utterly functional—”

“Functional?” scoffed Murchison. “Derailed a fully-powered hearse, rampaged through Kampong Glam—your man had to put it down.”

“We wanted tame golems, not a time bomb,” remonstrated Stroud. “Look at Narayan there. Why go to all that trouble if your creations won’t be half as tractable as he and his lot are? We’ve barracks of them, after all—boys who, when we say ‘jump’, say ‘how high, sir?’”

“I need more time,” pleaded Bradford, “it’s just a defect in the cognition engine, I’ll overwrite it in a jiffy…”

“Face it, man, you’re through,” Stroud said. “All this uproar has got the attention of the… shall we say more liberal factions under the Governor. There’s already been talk of an investigation.”

“You’re to be repatriated immediately,” added Murchison. “The rest of it will have to go, of course, the lab and all. The higher-ups want a full clearance report tomorrow. Where do you think you’re going?”

Bradford had got up and was fumbling in the liquor cabinet. “Do excuse me, I’m quite—something to steady the nerves—”

“Sit down, Bradford,” barked Murchison.

Bradford swung round. He was holding an antique shotgun. “Narayan, please see the gentlemen out.”

“Bradford…”

“I’m almost there,” Bradford shouted, “if you pull the plug now, you—”

Stroud shot him in the chest. It was a small, gleaming pneumatic pistol that slid easily back into his sleeve. Bradford dropped to his knees.

“Frightfully sorry it had to go this way, old chap,” continued Stroud, “but you see how it is. No hard feelings.”

He and Murchison rose. Stroud beckoned to Narayan. “The servants are gone, you said?”

“Yes,” said Narayan. His eyes were fixed on his master choking on his own blood.

“Take us to the lab, there’s a good fellow,” called Murchison. “Do step lively, we haven’t got all night.”

In the lab, Khairunnisa was elbow-deep in blood and metal springs. Ah Hong lay with her back to her. “Come on,” whispered Khairunnisa through gritted teeth, “come on…”

“What’s this then?” said Stroud cheerfully. “Our Dr. Bradford had himself a taste for the local flavour?” Murchison powered up the aether tank and aimed the nozzle at the drawers of bodies. Flames licked the blackening glass. “Oh well,” said Stroud, “she’ll have to go too. Narayan, you know what to do.”

Narayan stared at him.

Stroud gestured impatiently. “Everything has to go. Dispatch her first, then we’ll do you. Hare and I weren’t for it, you must know, but—orders. They’re saying you’ve lost your touch, what with that fiasco in Bussorah Street. You understand, of course.”

Narayan stepped towards the table. Khairunnisa’s hands kept moving. Her lips too, in prayer.

The flames were spreading. Murchison moved on to torch the ice cabinet, which resisted stubbornly. “Get on with it,” Stroud said irritably to Narayan.

Khairunnisa was crying, getting blood in her eyes when she tried to wipe away the tears. Narayan turned away from her.

“You can do your own dirty work, sir,” he said calmly. “There comes a time when a man tires of asking how high.”

The shot made Khairunnisa drop her instruments. Before her, the Gurkha collapsed quietly. He had made no move to dodge the bullet. Even in dying, his face did not change expression.

“Bollocks.” Stroud was angrily reloading the pistol. “Bloody natives. Can’t rely on them for anything.” He lifted the pistol again, meeting Khairunnisa’s frightened eyes.

On the table between them, Ah Hong sat up and tore the pistol from his hand.

Then she was on him, blow after blow to the face, pulping it against the tiles. The wound on her neck still gaping, the mechanisms within whirring furiously. Stroud’s hands scrabbled ineffectually against her broad back. Ah Hong crushed his lower jaw, then strained until it ripped free from his face.

Murchison turned in alarm, the nozzle flaring. A crossbow bolt thudded into his hand.

Ning limped into the room. She fired another bolt, which bounced off the tank. The nozzle, which Murchison had lost control of, was spilling flame wildly across the room. Khairunnisa scrambled out of its path.

Ning tossed the empty crossbow aside and went for her butterfly knives. Murchison pulled out a gun similar to Stroud’s, but could not fire properly for his wounded hand; Ning ducked his shot easily. Murchison tackled her. They went down together in a pool of blood and vomit, Murchison’s good hand landing blows where he could. Writhing to avoid him, Ning managed to force a knife up and stabbed Murchison through the eye. Ning clutched the hilt for dear life as he died above her face.

Across the room, Ah Hong was pounding what was left of Stroud into the floor. Ning got unsteadily to her feet. “Eh,” she said, “he’s giamcai already, you can stop.”

Ah Hong took a muzzy swing at her. Ning stayed well out of range. “Will you stop it? I’m not your enemy.”

“Still want to sell me?” snarled Ah Hong.

“I’m not sure you’ve noticed,” retorted Ning, “but trying to do anything with you is stupidly exhausting. And I’ve had it up to here with this night.”

“Everybody,” said Khairunnisa from the corner, “this room is on fire. I would really like to go.”

Outside the black-and-white bungalow, they took deep, welcome breaths of the night air. “Didn’t you stop working?” Ning demanded of Ah Hong.

“I fixed her,” said Khairunnisa. “Easier the second time round, actually. Didn’t you get left behind in my house?”

“Wasn’t hard to keep track of you,” panted Ning. “Speaking of which, please give me my eye back now, because I can hear trouble coming and I would like to be able to look it full in the face.”

A group of men was approaching. Ning recognized Chee in their lead. Chee was scowling. “Grandfather wants to see you.”

“Are you joking,” groaned Ning, “can a girl not get cleaned up first.”

“Grandfather said now,” repeated Chee grimly.

Ah Hong had her fists clenched, ready to attack. “Just go with them,” Ning told her in Malay. “Let me do the talking, it’ll be fine.”

“And if it’s not?” said Ah Hong through gritted teeth.

“Then you can punch them to death, whatever you like. Come on.”

~*~

Grandfather was eating a pre-dawn breakfast at a dimsum bar attached like a parasite to a garment factory. A great knot of pipes siphoned steam from the factory and vented it onto small columns of bamboo dimsum trays, which then went rolling out on little mechanical trolleys through the breakfast crowd. Everyone glanced at the stinking, bloodied women as they entered, but said nothing.

Grandfather picked up siewmai with his chopsticks. “Miss Ning,” he said without preamble. “You have not been discreet.”

“In my defense,” said Ning, “I was not the one who set fire to everything.”

“You have also worked too slow,” said Grandfather. “The tide has turned. The woman is now worthless.”

“Wait, wait.” Ning cocked her head at him. “You mean you don’t want her now? And I went to such trouble.”

“What for do I want her?” demanded Grandfather. “The only man who would pay ransom for her is dead. Now, if the British even realize she is still alive, we won’t see any money from them, just an extermination squad. This whole thing has been a waste of time.”

“I think it was more of a waste of my time,” snapped Ning. “I’m not getting paid?”

“You have the audacity, Miss Ning,” thundered Grandfather, ‘to ask for payment at this stage?”

“Grandfather,” said Ning with dangerous calm. “I have had a very bad day. I have been shot at. I have been punched in the head. I have been stabbed. And I smell like vomit. With all due respect, Grandfather, I think I should be paid.”

“That’s too bad, Miss Ning, because you won’t be.”

Ning gave a bark of laughter. “How far the secret societies have fallen indeed. Can’t even pay those they contract. Thought you were old school in this kongsi, but you’re cheap as any upstart crook.”

A ripple of anger ran through Grandfather’s retinue, stationed around the restaurant. “Perhaps a compromise,” said Grandfather. “We’ll cover the medical bill for whatever wounds you sustained.”

“And I get to keep the advance,” said Ning.

“Yes.”

“And I get her.” She pointed at a startled Ah Hong.

Grandfather raised his eyebrows. “Why would you want her?”

Ning shrugged. “You don’t. I’ll take her elsewhere. Maybe somebody else will be willing to pay.”

“The British will come after you for this,” pointed out Grandfather. “Be it on your head.”

“I’m not scared of the British,” said Ning. “Unlike some.”

She turned on her heel and strode out, Ah Hong and Khairunnisa following uncertainly. Nobody made to stop her.

“What happened?” Ah Hong wanted to know.

“Nothing much. I bought you. You were damn expensive.” Ah Hong stared. “I want breakfast,” Ning continued, “and then I want to never wear these clothes again.”

They ended up at a roadside coffeeshop. Ning drank black coffee and mashed liquid eggs with soy sauce in the saucer. Khairunnisa opted for milky tea. The whole ritual confused Ah Hong, who drank whatever Khairunnisa ordered for her and consumed mountains of thick toast smeared with coconut jam.

“What do I do now?” asked Ah Hong.

“I’m in the market for an associate,” said Ning. “I’ve begun to think that if I had a partner, preferably one who can squeeze out a man’s eyeballs with her fist, then I would spend less time bleeding and more time watching other people bleed. Also people would think twice about not paying me. That happens depressingly often.”

Ah Hong considered this. “Would you teach me back my language?”

Ning gazed at her thoughtfully. “I’d try.”

“We could put you back in touch with other samsui women,” suggested Khairunnisa. “Find people who knew you… knew the people you were from before…”

“No,” said Ah Hong quietly. “Nobody will come near me. Not when they know what I am.”

Khairunnisa stared into her tea. “What I saw down there. At the house. Allah will not forgive it.”

“He’s dead,” said Ning curtly. “The man who made her. He’s probably having a great time explaining it to Allah or whoever right now.”

“They’ll come looking for me, you know,” remarked Ah Hong. “They’ll always be coming.”

“When I ran away from the people who took my eye,” said Ning, “they kept trying to get me back. Eventually I proved to them it was more trouble than it was worth.” She looked at Ah Hong approvingly. “You’re going to be a lot more trouble than I ever was.”

Ah Hong smiled.

In a companionable silence, they finished breakfast and watched the sun rise over the island.