Chapter Two

Tools

Hardware

WITH TRAVIS MCELROY

We’re going to dive deep into the world of hardware here. If that sounds boring to you, you are very wrong! Once you learn a few basics, you’ll fall in love with this stuff just like I did.

If you are going to start a podcast, you are going to need a device to record it. You could try just going to every listener’s home to perform the podcast live, but I wouldn’t recommend it. The world of microphones and other audio devices can be daunting because of the wide array of options, so we’re going to do our best to simplify things by category.

Microphones

First, let’s start with the big one: MICROPHONES! When we started My Brother, My Brother and Me, Griffin was using the microphone that came with the video game Rock Band, and I was using a $15 combo headset/microphone that I got at Walmart. We would have gotten better audio quality if we had recorded using paper cups tied to pieces of twine. If you want an example of what you don’t want your audio to sound like, just listen to the first twenty episodes of My Brother, My Brother and Me. Just kidding! No one should ever listen to the first twenty episodes of My Brother, My Brother and Me. You know what, just skip to the mid-200s.

Since those horrible, horrible days, we have been on a search for the best microphone option for podcasting. In order to understand our recommendations, there’s some technical stuff we need to run you through. Try not to fall asleep.

There are three main types of microphones. I’m going to give you a pretty simplified description of each because I am no expert, and I’m guessing you aren’t either! They are as follows:

- Dynamic Mics: The workhorse of the mic world, dynamics tend to be sturdy and reliable. If you walk into any theater or live show venue, ninety-nine times out of a hundred you are going to find a dynamic mic in use. They do not require power to operate (more on that in a second) and can work in a studio setting or onstage. They aren’t as specialized as a condenser microphone, but they get the job done.

- Condenser Mics: Condenser mics pick up more detail than dynamics, but as such can require more fine-tuning in your gain settings. Condenser mics also require 48 volts of power to operate; this is referred to as “phantom power.” That means you can’t just plug a condenser mic into a computer and start using it. You are going to need a soundboard or some kind of interface between the mic and your recording device to provide those 48 volts. Condenser mics do very well in studio settings, especially for voice-over work and podcasting.

- Ribbon Mics: Ribbon mics are decidedly old school. They fell out of favor for a while, but there has been renewed interest in them recently. They are less sensitive to higher frequencies and tend to capture them without a lot of harshness. They’re great if you are going for a vintage-y feel in your recordings.

Recording Patterns

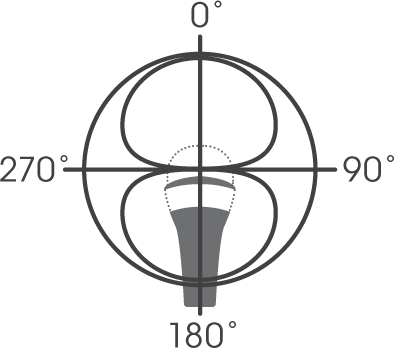

Recording patterns (sometimes called “polar patterns”) are the shape of the area that the microphone picks up sound from. Dynamic, condenser, and ribbon mics can come in any pattern you need.

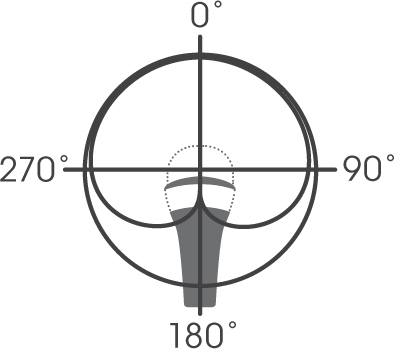

Cardioid

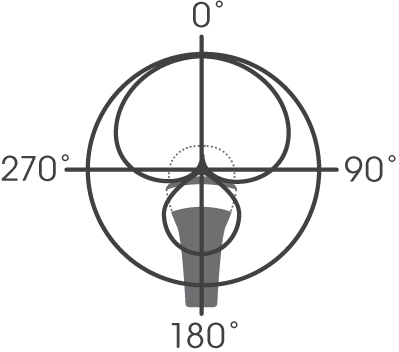

Supercardioid

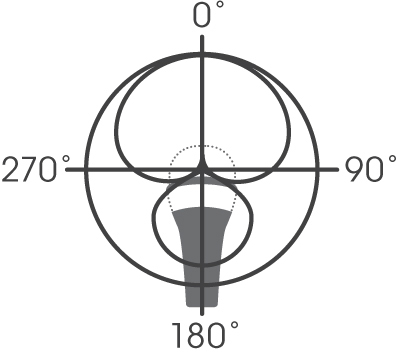

Hypercardioid

- Cardioid: Imagine blowing a bubble and you’ll be picturing a cardioid pattern. This means that the microphone is mainly picking up the sound directly in front of it. It will pick up some surrounding noise (that is how sound works, microphones are not magic), but it’s mostly only going to pick up sound from the person talking directly into it. This is perfect for scenarios where each person has their own microphone. There are also cardioid variations called supercardioid and hypercardioid. The super pattern has a slightly narrower field in front and a small bulb of sensitivity in the back. Hyper has an even narrower front field and a larger back field, which creates a more precise sound pickup but requires careful mic technique. In other words, when using this mic, if the sound being recorded moves off-center a little, you might lose it.

Omnidirectional

- Omnidirectional: Well, it says it right there in the name! This pattern is a circle of sensitivity with the microphone in the middle. It picks up sound in every direction at equal levels. This is ideal in a scenario where you use only one microphone to record a bunch of people at the same time. It is trickier to get a “clean” recording with omnidirectional, though, so if you plan on using this mic, it’s even more important that you choose a place to record without a bunch of ambient noise.

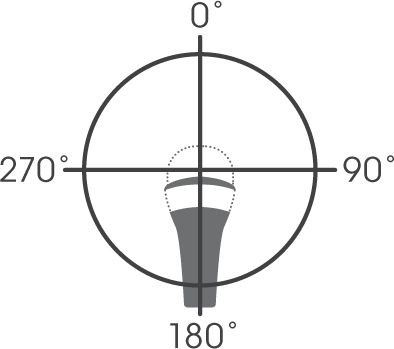

Figure 8

- Figure 8: With a figure 8, there is an area of sensitivity at the front of the mic and the back of the mic with very limited areas on the sides. This is great for a scenario in which there are only two people being recorded at the same time, though it’s not the best solution for a two-person recording, as it requires them to crowd around one mic. But it works great in a pinch.

Are you still with me? We’re almost done with the technical stuff, I swear! Only one last thing.

Cable Connections

How does your microphone connect to your recording device? Just like before, you can find all kinds of different mics with varying sound patterns that use either USB or XLR.

- USB: Simple to set up, a USB microphone cable plugs directly into your computer. Settings can be adjusted either on the microphone itself or through your computer. You have a lot less control over the recording, but it is also incredibly easy to get rolling. Though it’s the more straightforward option, only one USB mic can be connected at a time. If you want more, you’ll need . . .

- XLR: This is probably what most people would think of as a microphone cable. This cable connects to the mic and then into an amplifier, soundboard, or any kind of audio interface. Your recording will either be stored on a memory card in your interface or be saved to a connected computer. Because that interface serves as a middleman, you are usually able to tweak the recording way more than you would be able to with a USB connection. It can be the difference between one knob on the microphone versus thirty knobs on a soundboard. If you want to use more than one microphone in your recording, XLR is the only way (unless you want to involve multiple computers).

See, that wasn’t so bad! Now we can get into the fun stuff . . . shopping! You probably want to know which mic is best to start with. Well, it’s not really that cut and dry. First, you have to ask yourself: How committed are you to podcasting? If you want to try recording an episode or two or ten before you overcommit yourself, I would recommend a USB microphone in the lower-end range ($100 or less). There is a brand called Blue that has some really great, reasonably priced options. It might be a little awkward for you and your cohosts to keep taking turns talking into one mic, and the sound won’t be top-level studio quality, but you’ll be able to explore your newfound hobby without breaking the bank.

Here’s what I would not recommend as a budget option: a set of XLR mics for less than $40. It doesn’t sound like a lot at first, until you add in all the money you’re going to have to spend on cables and an audio interface (more on this in a moment). Getting a set of XLR mics should feel like an investment. When I first started podcasting, I made the mistake of always buying the cheapest set and then replacing it every time I could afford better. If I had just invested in a good-quality set of XLR mics to begin with, I would have saved a whole lot of money.

If you are ready to invest a little bit more in a USB mic, I highly recommend the Blue Yeti, which goes for about $130. Not only is the quality relatively good for the price, but you can also adjust the recording patterns among stereo (this is also called binaural; ASMR creators use this a lot), omnidirectional, cardioid, and figure 8. It’s a really versatile mic and very easy to set up.

It can be easy to get the impression that USB mics = low quality and XLR mics = good quality. This is not always the case. I used a USB mic for many years and was perfectly happy with it. I made the switch to XLR because I started recording with cohosts in the same room and I found that was easier to do with multiple microphones. To reiterate, you can really only use one USB mic at a time.

So, let’s say you are looking to switch from USB to XLR or you have decided to start with XLRs. There are some additional things you are going to need. First, you are going to need cables, XLR male-to-female cables specifically (the terminology is gross, I know). A good six-foot-long XLR cable is pretty affordable. Cables can be deceptively important when it comes to audio quality. I have found that a lot of audio issues end up being caused by loose connections or shorts in cables. I would also recommend having a few spare cables around; they can wear out over time (especially if you find yourself unplugging/replugging a lot). You would be amazed at how many times the answer to a technical or audio issue is “replace the cable.”

So now it’s finally time to discuss audio interfaces. Simply put, you plug your microphone into an audio interface and you plug the audio interface into your computer. They can range from a simple box with one input and one knob to a behemoth with a bajillion inputs, knobs, and switches. A simple interface isn’t going to break the bank, and a good-quality soundboard is going to start at around $100.

If you are like me, you may be looking to throw your whole self into podcasting right away and buy the “best” (read: most expensive) stuff right away. I would strongly warn against it. First, if you are inexperienced with a soundboard, one knob on the box interface is going to do you just as much good. Second, there’s no reason to splurge on a ton of expensive equipment before you know that you want to continue.

That said . . .

When you are ready to make that kind of investment, I highly recommend that you consider purchasing a Zoom. The Zoom, available in models H1 to H6, is a sound interface, recording device, and microphone all in one handheld machine. It’s perfect when recording audio at home or on the go. I have an H6, and I love it more than I love most people.

I hear you right now screaming, “Travis! Enough of this malarkey! Just tell me which mic to buy!” First off, there’s no need for that kind of language. Second, okay, you win! Here’s my suggestion . . .

The Shure SM58. I would say that nine out of every ten theaters we’ve done live shows at use them. Not only does the SM58 have good sound quality, it’s also very sturdy. Unless you are actively trying to destroy it, it’s going to last you a good long time. Now, the SM58 is going to cost you about $100, but it is totally worth it. So, if you are looking to get a set of mics for you and your cohosts and are willing to make an investment, this is the way I would go.

You may be wondering, “What kind of mics do the McElroys use?” We use CAD E100S microphones. We have tried out so many different mics, and we find that these work best with our voices and how we want our podcasts to sound. If you are really looking to make an investment and you want to sound like our show, there you go.

Now, let me tell you the dirty little microphone secret: more expensive doesn’t inherently mean better. Sure, you’re going to notice the difference between a $10 mic and a $500 mic. But what about between a $400 mic and a $500 mic? My rule of thumb is that once you get above $100, it comes down to personal preference. You might prefer the sound quality of a $200 mic over the $400 mic, and that’s totally valid. How do you know before you buy? Good news! There is a metric ton of microphone demos on YouTube that you can check out. Just search for the model you are looking for and have fun!

One last thing! An often-overlooked mic option is a lavalier or lapel mic. I have had success with a wired model that plugs directly into the XLR ports. I find this to be a perfect option if you are doing an interview-style podcast. You can easily clip the mic on to the guest and move on, which saves them from having to hold on to a mic or stay still in front of a stand. There tends to be a bit of a decrease in quality (these pick up a lot of background noise in my experience) but might be worth it for ease of use!

So, you’ve got your cables, interface, and microphones. Now, what else do you need?

Microphone Stands

You’ve got a couple options here. First, ask yourself: Do you want desktop stands or floor stands? The pros of a desktop stand are that it is compact, and if you are sitting at a table, it’s easy to position right in front of you. The con is that it will pick up vibrations and noise when you hit the table. The pros of a floor stand are you don’t have to worry every time you put your hands down on the table and it’s the only option if you are going to be standing up to record. The cons are that it’s larger and more cumbersome to position.

You can also decide between an articulated/scissor arm and a fixed stand. The scissor arm gives you a lot more maneuverability, but it is also a lot more sensitive to vibration sound. The fixed stand is sturdier but is limited in its positioning.

Headphones

I love headphones! There, I said it. It feels so good to finally get that off my chest. There are lots of people out there who don’t appreciate headphones as podcasting essentials, but not the McElroys. We use headphones in every single recording. This is partly because we are all in different locations and calling each other. However, even if we were recording in the same room, we would still consider headphones a pivotal part of podcasting production. Wearing headphones to hear your cohosts can improve the show in myriad ways. First, it can help you dial in and pay better attention to the conversation. It also allows you to hear the conversation the way the audience will be hearing it. You can monitor levels to make sure no one is too loud or too quiet. It can also help find audio issues that you may not be able to detect just by looking at the audio track.

No matter what, you should be editing the show using headphones. Once again, that is how most people are going to listen to the finished product, so it’s how you should be analyzing it. Whether recording or editing, I strongly recommend over-ear headphones. They reduce sound bleed when recording and allow for more isolation of sound when editing. Sound bleed is when you can hear the sound coming through the headphones in the recording. It creates a weird echo and can ruin a recording. If you are looking for more ways to avoid sound bleed, be sure to turn your headphone levels as low as you can.

If you are going to use headphones for recording with multiple people in the same room, be sure to get yourself a headphone splitter. A splitter is a cable that you can plug multiple headphones into and then plug that cable into one source. They range from a two-way splitter to a five-way splitter to a powered four-way splitter that allows you to set individual levels for each pair of headphones.

Windscreens and Soundproofing

At a bare minimum, you should get some foam covers for your microphones. I recommend getting the multicolored ones for reasons that I will explain in the next section. You might also opt to get yourself a windscreen. A windscreen is a thin layer of fabric stretched over a ring that you put between your mouth and the mic. If you, like me, have powerful plosives (p/k/t/g/b/d sounds), then this becomes a must-have.

There are also soundproofing options (foam squares, curtains, a panel that attaches to the mic stand) to help with your recording space, but I have found these to be, for the most part, unnecessary. They are effective, but podcasting doesn’t usually require a super pro sound quality level. However, if you are attempting to set up a full-blown recording studio space, it’s worth looking into.

Other Random Equipment

Get yourself a set of multicolored electrical tape and thank me later. You are going to use it to color-code your cables with your mic foam covers so you can quickly adjust levels for each mic without having to track which cables go where. You’re welcome.

You are also going to want to get a dog training clicker. While that sounds weird, it can make editing way easier. While recording, if you have an edit point, just add a few clicks right into the mic! When you are editing later, it will be very easy to spot the clicks in your track. Along those same lines, keep a notepad and pen nearby so you can make note of time codes for edits.

Looking for a pro-caster maneuver? Get yourself a cough button, my friend. Just like it sounds, it’s a button you can push to mute your mic while you cough, sneeze, take a phone call, or whatever. Release the button and it unmutes the mic.

If you are recording remotely (connecting with your cohosts/guests via the internet), you should be using an ethernet cable rather than Wi-Fi. It is almost always faster and more reliable.

This may seem obvious, but you are going to want comfortable chairs. You might be sitting there for hours and you don’t want to be shifting uncomfortably the whole time.

Perhaps the most important piece of hardware you can have . . . a beverage. Podcasting is just a whole lot of talking, my friends, and your mouth is going to get dry. Have a beverage handy—sip away!

Software

WITH GRIFFIN MCELROY

One of the biggest misconceptions about podcasting I frequently hear is that the technical aspects of pod-making are the big roadblocks. Talking for an hour with your buddies? That’s easy. You do that all the time. But when it comes to making the computer hear your talking, generating a good-sounding file, and then getting other people to hear that talking? Now that’s hard.

The inverse, in my experience, has always been true: once you scale the extremely scalable technical learning curve, working with software is a breeze. It is much, much simpler than being entertaining for an extended period of time, and also, you can eat snacks while you’re doing it (which you really shouldn’t be doing while recording, because yuck).

Unless it’s an ASMR podcast!

Actually Trav, I checked, and still, yuck.

Before breaking down the types of software you’re going to need in order to put together your podcast, I think it’s helpful to look at the goals you’re trying to accomplish with said applications. To get your mouth sounds into a computer brain and then onto the internet, you’re going to need:

- A way to record audio on your computer

- A way to edit audio files together

- A way to talk to remote guests or cohosts, if necessary

- A way to record backups of remote calls

- A way to make audio files sound better

- A way to create music for your show, if necessary

- A way to input the metadata (i.e., episode number, author, thumbnail image) on your finished audio file

- A way to upload your show to your hosting service

If you’re starting from scratch here, I’d be willing to bet you could solve a couple of those right now. You probably use Skype, Discord, Zoom, or some other VoIP (Voice over Internet Protocol) software to chat with remote friends; there is a bevy of serviceable options for chatting with distant cohosts. You can upload your show using any ol’ internet browser once you have a platform that can host your audio files—a whole ’nother kettle of fish that we’ll get into later in the book.

That’s good news #1. Good news #2: most of those requirements can be handled by a single application. One piece of software designed to streamline every part of the audio creation process. One executable to rule them all, and in the darkness bind them.

Your Digital Audio Workstation

I adore this terminology, because it sounds so overtly professional for the work I’ve often done with it. Oh, what software did I use to cut together this audio of three grown men talking about sexual Garfield fan art? My digital audio workstation. The episode where I ate, like, forty pizza rolls in nearly as many minutes? Well, that’s another opus lovingly crafted on my digital audio workstation.

As far as I can tell, any piece of software that allows you to manipulate audio files to create newer, better audio files counts as a digital audio workstation, or DAW. As you might imagine, it’s a pretty broad umbrella, as the term “audio” covers, well, a lot of stuff, obviously. Music, podcasting, narrative fiction, news reporting, atmospheric soundscapes—there are DAWs that are more targeted for each of those specific purposes.

For podcasting, I’d recommend going with a DAW that’s designed for spoken word content rather than the more musical end of things—though, really, it all comes down to user preference. I know plenty of producers who use Logic Pro X, Apple’s music-making software, to edit their podcasts.

Those three pieces of software—a VoIP, a DAW, and a browser—are really all you need to make a podcast. If you’re looking to go a little more high-touch, you can add music or really master your audio using external specialty tools. I’ll provide some recommendations later in this section.

But before you go any further in this book, you’ll need a basic understanding of what recording a podcast actually looks like. Computationally speaking. Physically speaking, in our case, it looks like a tired man wearing gym shorts, looming over his desk with unspeakably bad posture. You don’t need to emulate that. You should not emulate that.

The Digital Audio Workstation and You

Welcome to the most controversial section in this entire book. The software I use to make our podcasts, from single-track episodes of Wonderful! to thirty-track, highly produced Adventure Zone finales, is Audacity, an open-source, completely free DAW that I’ve been using for a decade now.

My brothers despise me for this fact. They harbor an open, profound hostility toward me because of my choice in DAW. I’m sure there’s some kind of sidebar here with one or both of them sounding off about how Audacity is unreliable, and their shit is so much better, and they don’t know why I was assigned to write this section of the book.

Fucking Audacity. Lemme ask you a question: How many times would a DAW have to crash, consuming your show and hours of work and shitting it into the obsidian nothingness, before you’d invest the literal minutes it would take you to learn new software? One? Two? A dozen? I’m seriously asking, because my little brother seems to have no discernible ceiling. I beg you to learn REAPER. It’s, like, $60 and there’s a generous free trial.

Audacity is a monster that has eaten my recordings in front of my face while I cried literal tears. I would never use it to record ever again. That said, I do use it for editing because it’s very user friendly.

I don’t think we’re allowed to do sidebars in our own sections, but I edit all the shows we do together, and I’ve only ever really lost, like, one file in more than ten years of doing podcasts. My brothers are actual babies.

Here’s the thing: Audacity is completely free, is really easy to start using, and has a nice, high skill ceiling for anyone looking to improve the quality of their audio work. You can easily pick it up, make some stuff, edit it, and export it for publishing like that, and as time goes on, if you want to get more detailed with your work, there’s plenty of stuff under the hood for you to learn how to mess with.

In short: it’s perfect for an amateur podcaster.

The best part about Audacity is that it can teach you the ins and outs of what you need out of a DAW with very little friction. If you find Audacity not to your liking, you’ll have that general knowledge of how DAWs work and what you prefer, which will make it that much easier to find your weapon of choice. I guess you could say it’s a gateway drug. Except for me. I still get very, very high on Audacity several times a week.

You’re going to be using your DAW for two distinct purposes: for recording and then for editing. Always in that order. (Please don’t try to edit audio you haven’t recorded yet, because that would mean you’ve slipped loose from the time-field and now somebody has to come get you.) We’re going to cross those two respective bridges when we get to them—for right now, it would be useful for you to have a basic understanding of how a DAW accomplishes those goals. I’m going to give a quick rundown on Audacity; if you’re at home, willing, and able, you may want to go ahead and download it yourself. It’s free, and it works on Windows, Mac, and Linux.

If you’re playing the home version of our game, I’ll give you a minute to finish the installation.

Okay, let’s proceed.

It’s beautiful.

It is objectively not. It’s a big gray block.

Travis is wrong.

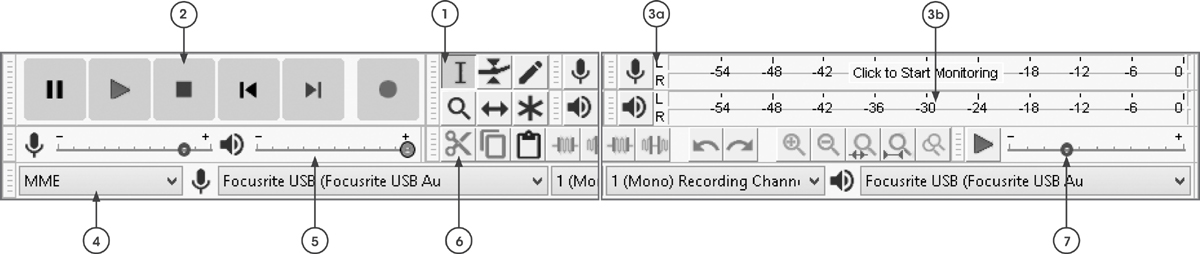

If you’re at all acquainted with any kind of media-editing software, that layout should look somewhat familiar to you. At the top, you’ve got all the tools you’ll need to move around the tracks you record, monitor them in real time, or manipulate them however you need. Below that is a single track in the project timeline, filled with my mellifluous voice, as represented by those sound waves. The menu bar at the top of the screen contains all the other functions of the software—effects, file management, etc.

The basic workflow of Audacity is fairly simple. After making sure your recording settings are on point—selecting the correct microphone, number of recording channels, and so on—you’ll record your audio. After you stop recording, you’ll have your one big chunk of raw audio that you can trim, apply effects to, or mix with other clips and tracks as your projects get more sophisticated.

Still, there’s probably some unfamiliar stuff on that screen, so let’s run through that real quick. (It’s okay if you don’t remember all this stuff; we’ll be dipping back into Audacity in later chapters, when it comes time to actually use it.)

We have our Tools Toolbar (1), which, yes, is a bit redundant. It speaks to the ease of use of Audacity that nearly all its main functions can be summarized in these six tools. (Honestly, I only ever use four of them!) These allow you to select sections of audio, adjust your zoom on the track, move clips around the timeline, and adjust volume levels at different points across the timeline.

Next is the Transport Toolbar (2), which should seem pretty familiar to you if you’ve ever, you know, watched or listened to any media. Pause, Play, Stop, Skip to Beginning, Skip to End, Record. Do you really need me to tell you what these buttons do? Shit, y’all. Get it together.

Next we’ve got two handy tools for making your audio actually audible: the Recording Meter (3a) and the Playback Meter (3b). The Recording Meter is what you’ll use while recording audio to make sure you’re coming in at a good level. The Playback Meter is what you’ll use while you’re editing and mastering your finished track, to make sure you haven’t made things too sonically unpleasant with all your ceaseless tinkering.

Below those is the Device Toolbar (4). You can use this to select the microphone and audio output device you’ll want to use for the project—or you can pick those through the Preferences menu, accessible (like most other functions of the software) through the menu bar at the top of the screen. You can also use the Device Toolbar to select the number of channels you want to record to, which is a slightly more complicated concept to grasp.

By default, Audacity will have you set to record on one channel, which is called “mono recording.” For, like, 99.9 percent of you, you’re going to want to leave that there. Think of a mono recording as being “flat,” where all the sounds contained within it are being delivered to the listener in a uniform manner. In stereo, your mic will pick up two channels of recording: left and right. Your voice has depth now. If you record the audio of an entire room—around the table for a board gaming podcast, for instance—you’ll simulate the positions of the people speaking.

Now, imagine your listener is riding their bike to work and only has their right earbud in. Everyone on the left side of the room? They sound like ghosts, wailing down the corridors of a very old pirate ship. That’s a dramatic example, but it’s one of many reasons you shouldn’t do your podcast in stereo sound. It’s disquieting to have the voices you’re listening to pinging around in your skull or, worse, to have two cohosts sharing the same mic divided up between earphones. It’s a pitfall I’ve seen a lot of early podcasts fall into, and you can avoid that same fate: keep it mono.

For the record, I do my show The Empty Bowl in stereo. I have a stereophonic track of crashing waves that I leave in stereo to give it a kinda cool surround sound effect. But what do I know, I’m just an artist.

Moving on from there, we have the Mixer Toolbar (5), where you can adjust your recording and playback volumes; the Edit Toolbar (6), which has a few handy functions that are also mapped to keyboard shortcuts (Cut, Paste, Trim, Silence, etc.); and, finally, the Play-at-Speed Toolbar (7), which lets you listen back to your project at whatever speed you choose.

Confession time: when I’m in a hurry, sometimes I’ll edit My Brother, My Brother and Me while playing it back at double speed. Ostensibly, I get through it twice as fast, though it makes it sound like I’m listening to a weirdly foul-mouthed Chipmunks holiday album.

If that seems like a lot, let me assure you: you’re not going to need to use most of these tools when you’re just starting out. The stuff you will use slots into a really logical workflow. You’ll find yourself needing a tool for a specific purpose—how do I move this clip from here to there?—and then you’ll find the solution just a few dozen pixels away.

Some Other Software You Should Know

Your DAW is by far the most important piece of software in your production pipeline, but you’ll probably end up using a few others to get your show made.

Here are some that I can think of:

- Skype, Discord, Slack, or some other VoIP to connect you and your distant cohosts. Assuming you have remote cohosts, you’ll need some way to talk to them. You likely have this figured out. We’ve used a few over the years, and don’t get it twisted: they’ve all got their little peccadilloes that make them problematic for podcasting purposes. Skype’s audio quality isn’t great, Discord has a tendency to duck audio when folks cross talk, Slack introduces delays from time to time, and so on. We’ve recently become big fans of a service called CleanFeed, which offers a browser-based voice chat solution that sounds fairly good—but its biggest selling point is that it also works perfectly as . . .

- An application for recording your VoIP calls. Most VoIP apps offer some method of recording right there in the app, which is what we do every time we record. This will give you one audio file with everyone talking on it. This should not be your first choice, if you can help it. The person recording the file will sound great; their mic is being recorded directly. Everyone else’s is going to get chewed up and spit out through the internet’s cavernous maw. You’ll have a version of your conversation saved, and if something goes horribly wrong with one of your cohost’s local recordings, you may need it for backup. But the recorded VoIP call will never sound as good as several local recordings edited together. CleanFeed is capable of recording each caller to separate tracks—but only if you’re paying for the premium version. It’s an improvement, but again, using locally recorded audio should be your goal.

- External audio processing tools. Your main editing software will likely include everything you need to get your audio in ship shape, but there’s plenty of stand-alone apps that can help streamline the post-production process before you get in too deep. I use an app called Levelator for virtually everything I edit. It’s free, and it can be used on Windows, Mac, and Linux. You take a WAV file (the most common audio format we use throughout the production process), drag and drop it into Levelator, and it will process the file and establish smooth, uniform audio levels throughout. It’s a shortcut I heavily rely on, and you should too.

- A DAW for making music for your show, if that’s something you’re into. I use Logic Pro X, which is Apple’s professional music production software, to make all the music for The Adventure Zone. If you’ve got a Mac, you should have free access to GarageBand, which has a metric ton of loops and instruments for you to futz around with, but I don’t really have time to provide a tutorial for that here. (You should go goof around with those, though, because they’re rad as hell.) There’s a cornucopia of options for other operating systems as well—Ableton, Pro Tools, FL Studio, you name it. There are massive online communities dedicated to these DAWs, and learning how to use them isn’t nearly as difficult as you might think.

- An application for finalizing your metadata. Like I mentioned earlier, your finished show will need some baked-in information that can surface for listeners when they listen to it. You know how iTunes tells you the artist behind a song and the name of the album it’s on and shows you the cover art of said album? That’s all metadata. Audacity will let you set pretty much all of that when you export your file, but I use an app called ID3 Editor to finalize all our episodes, just as a means of double-checking that everything looks good from the listener’s end before we publish.

- An internet browser. You’ll need one to upload your show to your hosting platform, which we’ll cover when it’s time to talk postproduction.

If I can add one more consideration when you’re getting your slate of software ready to go: don’t be afraid of this stuff, especially your DAW. Audacity is about as user-friendly as software gets, but even if that weren’t true, remember that nobody has to hear everything you create with it.

Record yourself singing some random garbage, then go up to the Effect drop-down menu and get weird with it! Make some shitty harmonies over multiple tracks! Do impressions, and then try to chop and screw them into lo-fi beats. Then delete them! That kind of toy box approach to learning a DAW is an effective—and fun!—way to start gaining experience and confidence with its suite of tools.

Where to Record

WITH JUSTIN MCELROY

You tug on the heavy door of the studio and hear an odd shwush as air rushes out of the room. The walls are covered by weird divots, giving the impression of the world’s largest egg carton. The lighting is dim but comforting. The chairs? Beyond comfortable. And then there’s the strangest bit: the way sound seems to die as soon as it escapes your lips. The team of engineers you’ve got monitoring your every word gives the nod and presses the Record button. This is a professional studio and . . . you don’t have one. (Well, we’re assuming you don’t have one; it would be weird that you’re spending your precious life minutes reading this if you had one of those.)

The good news is that with no more than a few bucks and a little know-how, you can fashion a recording space that’ll be just fine.

Besides, studios can smell weird. Think about how many people have gotten their spit all over those microphones. Trust us, our dad worked in radio for years and the smell still haunts us. (To simulate: find the oldest blanket in your closet and find some old dudes to blow cigarette smoke into it for thirty years. Ugh, pass.)

Less Than Ideal Is Ideal

Even though your own private recording studio isn’t realistic, it is a useful metric to work off of.

The dream studio would be:

- Completely accessible to you at all times

- Completely silent and impermeable to outside noise

- Perfectly treated to dampen sound waves (more on that in a second)

- Perfectly comfortable

You won’t be able to meet these ideals (that would be a professional studio, right?), so the trick is trying to get as close as reasonably possible. Imagine those four criteria like little sliders. You want them each to be as high as you can get them. They don’t have to be at ten, but if any of them are at zero, you’re not going to have much success.

If you have a space that’s usually accessible to you that’s sort of insulated from outside noise and basically treated to dampen sound waves while still being kinda comfortable, you’ve got an ideal space to start podcasting in.

I’m going to assume that the concept of accessibility is one that needs no further explanation, but let’s take the other three factors one at a time.

Secret Pro Shortcut

Sorry, I should have said this earlier, but there’s a really easy solution to this whole thing, and if it makes sense for you, I don’t wanna waste a bunch of your time. So, here it goes:

Record in a closet, specifically one filled with clothes. That’d be ideal. If you could just shove yourself into a closet and record by yourself (or squeeze in a bunch of your friends), read no further. Just do that.

This is a short-term fix probably (especially since the closet might get a little muggy during a lengthy recording session), but if you just wanna get started immediately, it’ll meet most of the criteria, trust me.

Silent but Deadly

There are two different kinds of sound you have to consider when you’re recording: the kind you make while recording your show and the preexisting kind. We’re gonna talk about the second one first, because I’m a structural rebel who never learned to play by The Man’s Rules.

Close your eyes right now and really—oh, crud, you stopped reading. Hmm, I’ll wait until you open them again. Okay, so close your eyes—not yet—but in a second, close your eyes and really focus on what you hear. See how many different sounds you can isolate.

Welcome back! First, wasn’t that relaxing? You should really try to do that more often. Second, how many different sounds did you notice? I’m on my porch, so I heard my baby’s white noise machine through the window, a car, some birds, the wind in the trees, a distant Weedwacker, and the Twin Peaks soundtrack, which I listen to while I write to give my prose the appropriate amounts of melancholy and nostalgia. Any one of these noises could be really bad for a recording, so I would recommend that you not record on my porch. Let’s find a more secluded corner of the house, okay?

Small spaces on the top floor are nice, because you’re not going to get foot traffic noises from higher floors. Basements are good, unless there are a lot of creaky floorboards above you or the Wi-Fi can’t reach. Unless you’re on a top floor, it’s a good idea to have someone jump up and down and scream right above your recording location to see how much sound leak you can expect into your recording space.

At the very least, your space needs to be behind a closed door so anyone you share your home with (pets included) can go about their lives without messing up your show.

There are less obvious, more insidious noises to be aware of as well. You’ll want to shut off any fans in your space. Also, crank up the air-conditioning and listen for a hum or buzz. If it comes through on playback, you’ll want to shut it off before you record.

There have been episodes of My Brother, My Brother and Me (especially from the early days) that we’ve had to dispose of because we couldn’t be troubled to turn our AC off. Don’t be like us, you’re better than that.

Processing Audio Complaints

I’ve actually found listener feedback on audio quality to be one of the most useful tools when troubleshooting your space. Much like you don’t notice the smell of your own home, your ears (especially if you’re just starting in audio) may have learned to ignore certain sounds. You may no longer hear echoey voices, air-conditioning, pet noises, your children asking you to stop writing your podcasting book long enough to look at their drawing they made at school, etc., but your listeners will pick up on it instantly.

Other culprits to look out for: noisy PC or game console fans that you’ve learned to tune out, space heaters, and aromatherapy machines that make a bubbling sound that drives your younger brothers absolutely apeshit.

P.S. I’m so fucking sorry that I have an anxiety disorder and I like a little lavender in the air to help me unwind, Travis. Maybe you should find a different brother who’s a little less complicated, eh, Griffin? What’s that, you haven’t got another brother? Oh, weird, maybe you should start treating this one a little nicer then.

If you’re ever in doubt about how much ambient noise is bleeding into your studio, there’s only one reliable fix: turn on your microphones, record the room without any speech, and then play it back. You’ll probably never get complete silence, and there are some tools you can use after the fact to clean it up, but get it as close as you can.

Intentional Noise

Podcasts are, of course, a creative medium and as such have no actual rules per se, even as it pertains to your recording space. Background noise may be very important to providing a sense of place—for example, crickets to convey that you’re recording on a quiet, peaceful night.

I would contend that even if the noise is intentional, you’d be better served recording your audio in a silent room and then recording your background noise separately to give you control over how loud those background sounds will be.

Sydnee and I once did an episode of our TV podcast Satellite Dish while driving. We thought it would give the whole thing a fun road trip vibe, but the noise of the engine made it almost unlistenable.

These days, I’m smarter. For example, I mentioned my meditative show The Empty Bowl earlier, which includes the sound of waves crashing. I keep these background sounds on a separate track so I can lower the volume when I need to.

A Beautiful Pillow Room

Just a warning that I (Justin) am getting way the hell out of my depth here in this section, as it deals with a lot of acoustic science that I barely understand. But listen, you just need to trust me, okay? I’m a professional podcaster, and you’ve already paid for the book.

Once you’ve eliminated as much exterior noise as you can, you’ll need to control how the sounds you make with your mouth and kazoo (applicable to kazoo-centric shows only) bounce around the room.

Here’s the layman’s version of this: when you talk you make sound waves. Some of those waves go into the microphone, but some go shooting around the room and bounce off any hard, flat surfaces they can find. Those sound waves are reflected back to your microphone just a nanosecond or so after your initial burst of mouth audio, creating a bunch of very tiny echoes. These sound bad, generally speaking.

Wanna hear a great sample of this effect? Download episode fifty-five of My Brother, My Brother and Me. It’s one of the only times we ever recorded all in one room outside of a live show. We recorded in our dad’s office, and it was completely untreated, so you’ll hear some pretty harsh echoes. Why were we all in the same room, you ask? Well, our Mawmaw Lou passed away, and Travis and Griffin were in town for the funeral. And I . . . don’t know why I just told you that. Let’s get back to podcasting.

The solution? Eliminate as many of those hard, flat surfaces as possible. Here are a few possibilities:

- Spend a bunch of money on acoustic panels to hang on the walls and ceiling: Great choice, but pricey. There are cheaper tiles you can buy online in bulk, but I haven’t found them to provide much noise dampening.

- Build them yourself on the cheap (tutorials are all over YouTube): Also a good choice, but it’s a ton of work, and what if you accidentally staple your fingers to them?

- Put a bunch of bookshelves in the room: This was my strategy for the first few years we made podcasts. Books are fantastic at absorbing sound, and their irregular shapes make them ideal for diffusion.

- Moving blankets: You know, the big boys that you throw on your armoire to keep it from getting dinged up in a move? These are cheap and thick, and you can hang them basically everywhere. They just don’t, you know, look great.

- A rug: Oh God, look down—what’s that giant reflective surface? That’s right, your floor. Hey, don’t panic! Maybe just toss a rug down there.

- Clothes: Like in a closet? But you better not have a closet you can record in, because then you spent all that time reading this section for nothing.

One solution I wouldn’t mess with are mic isolation shields. These are like giant foam binders, and you prop them in front of your face while you record. They block your view of your computer and other people you’re recording with, and they’re not all that effective to begin with.

The best fix for you is probably some combination of all these treatments. I record in a carpeted room with plenty of bookshelves and acoustic panels that I installed a couple of years ago. It’s still not perfect, because I have a large desk, computer monitors, and a TV that all reflect sound. But it’s pretty good, and that’s okay by me.

If you’re using a really great directional microphone for podcasting, this may not be that big of an issue, because they’re designed to pick up just the mouth sounds as much as possible. But having a well-soundproofed recording space certainly doesn’t hurt.

Testing is the answer here: make a recording before you start fooling with soundproofing. Talk, cry, scream, laugh, whatever, and then play it back and listen. If the echo isn’t bothering you, it probably won’t bother your listeners.

Getting Comfortable

This isn’t the first factor everyone considers when they’re picking a studio space, but that’s not a surprise. You can live with discomfort, right? Sure, the woodshed you record in is sweltering for half the year and freezing for the other half; sure, its “chairs” are rusty wrought-iron benches and the windows are positioned specifically so the sun can shine directly into your eyes sixteen hours every day. But it’s quiet, isn’t that enough? Friend, I’m here to tell you it’s not.

You’re an artist, after all, and you can’t make your podcast art if you’re distracted by how much you’d like to watch your folding chair fall silently into a bottomless well.

When my wife, Rachel, and I started recording podcasts together, she would sit on a piano bench in my office while I sat in my futuristic, orthopedically optimized Big Boy chair. The discrepancy between our situations was untenable, so I picked up a padded folding chair from Target—which Justin, upon viciously criticizing me, one-upped with an even fancier Big Boy chair he gifted her for her birthday. This is a long way of saying that I am, all things considered, a deeply thoughtless person, cohost, and husband.

That’s not to say you should be sitting at all, of course. Ideally you’d be standing. It’s better for your health, vocal performance, and energy levels if you stand.

I mean . . . I don’t. I don’t stand, I sit, and I’m wild about it. But I should stand, and you should too. So, comfortable chairs are a must. Just make sure they’re not squeaky (for obvious reasons).

Back to temperature. I always have my air-conditioning off when I record, so I run it at full blast right before I record to get the room comfortable.

Good lighting is important too, but that’s really more a question of preference. I find overhead light really oppressive, so I tend to rely on lamps or open the blinds during the day.

Clutter is something I wish I’d taken more seriously when I started making podcasts. If your recording area is messy, you’re just not going to be in the best headspace for making great stuff. (This obviously doesn’t apply to you if you’re the kind of total dirtbag who just has to have it filthy. I’m not here to judge.)

Hey, you know, a bit of decoration might be nice. I like to surround myself with things that inspire me creatively, which is why I’ll never take down my seven-foot-tall Borat poster, no matter how much sound it reflects.

Okay, I could go on and on here, but I’m basically spiraling into home decor advice that I’m wildly unqualified to give. You get the idea.

Every Little Bit

If there’s one consistent theme to our podcast advice, it’s one of iterative improvement. No one is going to be perfect at the start, because no one is ever perfect. That’s absolutely applicable to recording environment.

Are you going to have a perfect home studio from episode one? Probably not. Have there been plenty of successful podcasts that have launched in the exact same scenario? A ton of them.

The key thing is that you’ve put a bit of thought and energy into making the best recording environment you can reasonably create. From there it’s just a matter of making improvements to your space when it makes sense.

And at least try standing.