Anglo-Americans . . . conceive a high opinion of their superiority and are not very remote from believing themselves to be a distinct species of mankind.

Alexis de Tocqueville, 1835

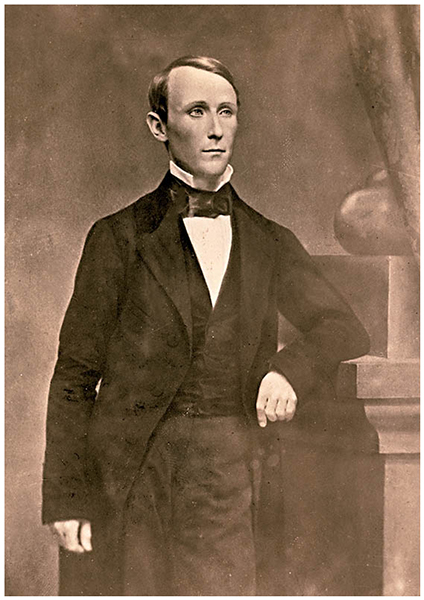

I n May 1856, the administration of President Franklin Pierce extended diplomatic recognition to the newly established government of the Republic of Nicaragua. This would seem a rather ordinary turn of events, except for the fact that the government of the new republic was headed by an American by the name of William Walker (1824–1860). Walker’s followers dubbed him “the grey-eyed man of destiny.”1 He was one of several “filibusters,” a term used to describe American soldiers of fortune in the 1850s who attempted to seize lands in Central America and the Caribbean through revolution and subsequently transform them into slaveholding states modeled after those of the South. Walker, with a private army of sixty men, intervened in a Nicaraguan civil war and successfully took over its government in 1855. As president of Nicaragua, Walker repudiated an 1824 edict emancipating slaves, intending to set up a new slave republic south of the Rio Grande. He also encouraged Americans to settle there as colonists in the same way Americans were invited by Mexico to settle in Texas in the 1820s.

Figure 1.1. William Walker, the “grey-eyed man of destiny”

But Walker was not of a mind to win friends in his new position. In addition to making powerful enemies all over Central America, Walker managed to alienate one of his chief American benefactors, Cornelius Vanderbilt. He seized control of Vanderbilt’s steamship assets and handed them over to his cronies. After being defeated in battle by a coalition of Central American forces, Walker was able to flee to the United States. And when he rolled the dice on another filibustering expedition in 1860, this time in Honduras, he was captured by the British navy, handed over to Honduran authorities, and executed by firing squad. If you are seized by curiosity, you can go to Trujillo on the northern coast of Honduras to see his grave.

Why on earth would anyone attempt such rash adventures? Walker’s motives were animated by the cause of “manifest destiny,” the idea that God by his providence had ordained that the United States would overspread the North American continent, and perhaps beyond. Walker sought to establish the institution of slavery in Nicaragua, as well as the English language, and fiscal policies that would attract and develop a white population in Central America. Walker hoped these policies would prepare the way for the United States to ultimately annex Nicaragua, in the same way it annexed Texas in 1845.

The story of the swashbuckling “man of destiny” William Walker, as bizarre as it seems to those of us on this side of sanity, is an example of what closed exceptionalism could lead to in the mid-nineteenth century. During the early national period, that is, the period from the ratification of the Constitution until the opening of the Civil War (1789–1861), closed American exceptionalism largely took shape. By the time the Southern states seceded from the Union in 1861, much of the American populace had accepted closed exceptionalism in the form of manifest destiny. By the end of the Civil War, slavery and secession were dead and another articulation of exceptionalism was championed—namely, the open exceptionalism of Abraham Lincoln. Thus, by 1865, the two forms of American exceptionalism, closed and open, were formed and continued to develop as the decades of the American experience progressed.

What are the origins of American exceptionalism? Where did the idea that America served as an exception to the norm of nations everywhere else in the world come from? How, why and when did closed and open exceptionalism develop, and who would be among their most persuasive spokesmen? These questions are the subject of this chapter.

Imagine for a moment that the idea of American exceptionalism is a tree. The tree’s root system is intricate and deep. The trunk of the tree splits into two near the ground, becoming a multistem tree, like a maple. One trunk develops its own branch system independent of the other, but they both originate from the same root system. Closed and open exceptionalism are like this multistem maple tree. They are two trunks forming the same tree arising from the same root system.

There are four main root systems of the tree of American exceptionalism. These root systems are theological, political, exegetical and historiographical. Out of these root systems grows one tree, American exceptionalism, which separated into two trunks, closed and open, during the nineteenth century. Territorial expansion and the spread of slavery shaped and nourished the trunk of closed exceptionalism. That of open exceptionalism was bent and twisted by opposition to slavery and pruned by Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War, preparing it for growth and development into contemporary times.

As an aspect of civil religion, exceptionalism entails distinct theological elements. Exceptionalism in general consists of an invocation to God; closed exceptionalism entails God’s special favor on the nation. Both closed and open exceptionalism acknowledge divine providence, although in differing ways. American exceptionalism’s theological roots are found in the Puritan worldview, and in particular, those Puritans who settled and flourished in the New England colonies during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

It is important to acknowledge here that the Puritans represent but one religious group among several in the colonial period. Religious diversity within the Christian tradition in the British North American colonies was a given, since a variety of religious groups were involved in most of the thirteen colonies’ founding. And as the Great Awakening got underway in the early to middle 1700s, that diversity became even more pronounced as evangelical groups such as the Baptists and Presbyterians became more populous. But the Puritans were perhaps the most influential intellectual group during the colonial period. In 1835, Tocqueville went as far as to say that “I see the destiny of America embodied in the first Puritan who landed on these shores, just as the whole human race was represented by the first man.”2 Through the enormous volume of Puritan writings in the form of sermons, books, pamphlets, newspapers, letters and so on, Puritan thought spread from New England to the Middle and Southern Colonies as well as to the western hinterlands. George McKenna wrote that the Puritans were, more than any other religious group, behind “an emerging sense of American nationhood, a realization that America was something more than a patchwork of villages, towns, and regions.”3

The history of the Puritans in England and America, while fascinating, is beyond the scope of this study. Suffice it to say here that many Puritans in England, after failing to reform the state church from within, migrated to America and established colonies in what became known as New England in the first part of the 1600s. Their theological positions were defined largely by Calvinism, and they sought to integrate theology into a worldview encompassing every aspect of life and thought.4 McKenna noted that Puritan thought provided what became a coherent framework or scaffolding around which American self-identification was constructed. It is my contention that three theological ideas in particular shaped that framework: the Puritan understanding of covenant, typology and millennialism.

Covenant. Central to the Puritan worldview was the concept of the covenant, an earnestly solemn communal arrangement between the people and God. The Old Testament provided the model for a covenant community, specifically that covenant that existed between the children of Israel and Yahweh, mediated by the law of Moses. In short, the people of the covenant community committed themselves wholly to God’s care, trusting in him for protection, provision and blessing. Their responsibility as God’s covenantal people was to obey his commandments and walk faithfully in his ways. In response to the people’s faithfulness, God would bless them and establish them in the land, and demonstrate his own faithfulness to them by exalting them before other peoples as they humbled themselves before him. John Winthrop, the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, articulated this covenant concept in his famous treatise, “A Model of Christian Charity.” According to Winthrop, if the people were faithful to obey God’s commandments, then God would “please to heare us, and bring us in peace to the place wee desire, [and] hath hee ratified this Covenant and sealed our Commission.”5 If, however, they became unfaithful to their identity as God’s covenant people, then God was certain to punish them, to “surely breake out in wrathe against us, be revenged of such a perjured people and make us knowe the price of the breache of such a Covenant.”6

The covenant as a structural theme in the Puritan conception of culture was articulated brilliantly in the literary genre known as the jeremiad. Preachers and writers employed this unique style of literature to shake the people awake and out of their spiritual and ethical lethargy and call them to repentance from their sin and to return to faithfulness to God.

Unlike most of us in contemporary times, when some calamity befalls a group of people, the Puritans’ first thought was not to assign some natural explanation to it. When a hurricane devastates a community in our times, for example, most of our thoughts go to things like climate change, lack of wind shear, or elevated surface temperature of the ocean when we attempt to explain its course, its strength and why it happened in the first place. But the Puritans’ first thought after experiencing a crisis was simply God’s meticulous providence. This view of providence has in mind that every single thing that happens (or does not happen), down to the minutest of details, is directly attributable to God’s intentional activity in his world. A famine, a disease, a drought or an Indian raid—the Puritans habitually thought God used natural events like these to directly respond to their backsliding, their sinful neglect of their covenant with him.

During the second half of the 1600s, the jeremiad arose as an inimitable Puritan—and by extension, American—literary genre. It took on new efficacy in the wake of the disaster of King Philip’s War (1675–1678), in which the Puritan colonists and their Indian allies fought against the Wampanoag tribe under Metacom (King Philip to the English). Both sides were devastated. The native population was reduced from a quarter of all inhabitants in New England to a tenth, and one in sixteen English settlers were killed.7 Larry Witham wrote, “After King Philip was killed in August 1676, and his severed head stuck on a pike in Plymouth, ministers poured out their Jeremiah-like interpretations through the printing presses.”8 The first drop in a flood of jeremiads was likely Michael Wigglesworth’s 1662 poem, “God’s Controversy with New England,” written in response to a drought. Jonathan Mitchel wrote “Nehemiah on the Wall in Troublesome Times,” a 1667 election-day sermon. In 1670, Samuel Danforth preached his “Brief Recognition of New England’s Errand into the Wilderness,” which provided one of the first lists of Puritan sins. And in 1702, Cotton Mather published his monumental Magnalia Christi Americana, which was a providential history of the New England colonies. Witham called Magnalia “a sustained jeremiad.”9

This Puritan conception of covenant entailed a special calling on them as God’s chosen people with a divinely ordained mission. Even though they believed they existed as the people of God, they were always cognizant of the enormous responsibility that came with that privileged position. As they read the Old Testament, they saw not only the ancient Israelites existing in covenant relationship to God; they saw themselves.

Typology. In the Christian tradition of biblical interpretation, typology has served as a consistent method in demonstrating the symbiotic relationship of the Old Testament and the New. Christian biblical interpreters have recognized for millennia that the key to the harmony between the Old and New Testaments is the person and work of Jesus Christ. Christ made the Old Testament meaningful. Thus, for example, the Israelite exodus from Egypt served as a type, a foreshadowing, of the antitype, namely, the Christian’s passage from death to life made possible by the atoning sacrifice of Christ on the cross. David as the king of Israel served as a type of Christ, who is at once the eternal King of the Jews and the King of kings who will personally come to reign at his second advent. The return of the captives from Babylon in the late sixth century served as a type of salvation, which is the work of Christ alone. And there are many, many others.

Sacvan Bercovitch identified the significance of the Puritan practice of seeing themselves and their experience as colonists in New England in typological terms. The Puritans extended the hermeneutical method of typology from mere biblical interpretation to a providential interpretation of secular history as well. They were not the first to do this—this practice dates back to the earliest centuries of the church—but they consistently saw themselves as key players in salvation history. Scripture served as a benchmark for the interpretation of God’s work in both sacred and secular history, since God’s activities had not ceased with the death of the apostolic generation. Bercovitch wrote, “In effect, they incorporated Bible history into the American experience—they substituted a regional for a biblical past, consecrated the American present as a movement from promise to fulfillment, and translated fulfillment from its meaning within the closed system of sacred history into a metaphor for limitless secular improvement.”10 He also said, “It became the task of typology to define the course of the church (‘spiritual Israel’) and of the exemplary Christian life.”11 By employing this literal-historical interpretation to Scripture, the Puritans saw themselves as active agents in God’s overall program for human history. We will later see how typology’s relation to millennialism factors into the Puritan interpretation of history and their view of themselves.

For now, what were some of the figures in Puritan typology? In other words, how was typology applied in the Puritan theological system? Several examples can be readily identified. The nation of Israel was a powerful figure in Puritan typology. Samuel Danforth, in his “Brief Recognition of New England’s Errand into the Wilderness,” saw that the Puritans who were carving out a civilization in the wilderness of North America were much like the children of Israel wandering in the desert. The children of Israel were on God’s errand in the wilderness as were the Puritans. Danforth asked, “To what purpose did the Children of Israel leave their Cities and Houses in Egypt, and go forth in the Wilderness? Was it not to hold a feast to the Lord, and to sacrifice to the God of their fathers?”12 But during their sojourn, the Israelites forgot their God and turned inward. They became dull to God’s law, and God judged them because of their rebellion. Danforth went on to ask, “To what purpose then came we into the Wilderness, and what expectation drew us hither? Was it not the expectation of the pure and faithful Dispensation of the Gospel and the Kingdom of God?”13 Just as the children of Israel had turned their backs on God in the desert, so were the Puritans dangerously flirting with the same sin. Danforth was identifying ancient Israel with his own people, not just as a powerful sermon illustration, but as a type. As God’s new Israel, the Puritans could look to the example of ancient Israel and understand exactly how God would deal with them, for well or ill, depending on their faithfulness to him as his covenant people.

There were other powerful figures featured prominently as types in Puritan writings; for example, in Mather’s Magnalia, the churches established by the Puritans were the golden candlesticks of Revelation, shining the light of the gospel in the dark recesses of America. The prophet Nehemiah served as a type of John Winthrop. Mather referred to Winthrop in exalted terms, as Nehemias Americanus in the fourth chapter of the first volume of Magnalia. And the Puritans generally took the New World as a whole to be more than just a piece of land separated by the sea from Europe, but the stage on which God was about to bring to fulfillment all of history. The New World was Canaan, the Old World, Egypt. God had brought his chosen people out from the oppressions of the old country and into the wilderness. They were to prepare the way of the Lord, much as John the Baptist was to fulfill Isaiah 40:3-5 when he went into the wilderness to prepare Israel for the coming of the Christ. As Bercovitch wrote, “The remnant that fled Babylon in 1630 set sail for the new promised land, especially reserved by God for them. . . . Unmistakably, the New World was part of the history of salvation.”14

Millennialism. The third aspect of the Puritan theological structure I am identifying is the notion that history is progressing toward a Christian utopia, that God is using nations to bring about his kingdom on earth—and as Ernest Lee Tuveson wrote, “The finger of Providence had pointed to the young republic of the West.”15 The millennium is the biblical thousand-year reign of Christ, described in Revelation 20, to begin after the second advent. Satan will be bound and imprisoned, Christ will personally reign on the earth and his church will reign with him. The millennium precedes the final and absolute defeat of Satan, the creation of the new heaven and the new earth, and the ushering in of the eternal age.

Millennialism is a view of history that sees humankind progressing toward the second coming and the personal reign of the glorified Christ. According to this view, humans actually take part in laying the groundwork for the millennial kingdom, through obedience, spreading the gospel to the uttermost parts of the earth, and establishing the Christian ethical ideal through the expansion of Christian civilization. Further, God’s agents in preparing the world for the millennium are the nations, and particularly those nations that represent him faithfully. To the Puritans, and later the American colonists as a whole, America was the millennial nation.

Prior to the Reformation, Western civilization had not understood history to be progressing toward any particular telos through the active agency of human beings. During the Middle Ages and through the Renaissance, Augustine of Hippo (AD 354–430) provided the West with the prevailing view of history in his work The City of God. Augustine cast civilization in terms of two groups, or cities: one was the city of man, the other, the city of God. The city of man, for Augustine, consisted of the empires established by human strength and greatness, like the Roman Empire. Human empires, while powerful, were bound up in time and ultimately doomed to fall. But the city of God consisted of those who were faithful to Christ, that is, the church, which for Augustine equated to the kingdom of God on earth. The city of God would be persecuted by the city of man, but ultimately will prevail when Christ returns and judges the living and the dead at the great white throne (Revelation 20:11-15). The millennium described in Revelation, according to Augustine, is not to be taken literally, but allegorically. The thousand years in Revelation 20 denote a long and indefinite period of time—thus Augustine’s eschatological position is termed amillennialism (“no millennium,” no “thousand years”). Since his resurrection, Christ reigns over his people, the church, and Satan’s binding takes place from Christ’s resurrection until the second advent. At that time, Satan will be released only to meet his final destruction in the lake of fire. The city of man is doomed to follow him there.16

The upshot of Augustine’s view of history is that, even though Satan is bound during the age of the church, ills resulting from Adam’s fall still persist. This condition is not going to change, at least not until Christ’s return at the end of the age. If evils can still wreak their desolations upon humans, even while Satan’s power is muted, then surely nothing can be done by mere mortals to improve their lot. It is vain for humans to try and effect hope in this transitory and decaying world. The only answer is to wait for a better world in the afterlife. This was the prevailing view of things in western Europe during the roughly thousand-year period from the fall of Rome to the sixteenth century.

The Augustinian view of history was supplanted by a new view, one that came about as a result of the Protestant Reformation in the sixteenth century. A general reconsideration of the meaning and authority of the Bible was central to the project of the Reformation. Included in this reconsideration was a new interpretation of the book of Revelation, and with it, the meaning of the millennium. Perhaps Revelation pointed to an actual thousand-year period in the not-too-distant future, when true Christian civilization would reign triumphantly over the forces of the devil and the Antichrist. Could it be possible that God would actively use the nations to bring about this triumph? If so, then it would seem that humanity could bring about the culmination of history after all. Instead of forlornly waiting around for Jesus to return, humans could effect the glorious reign of Christ by their own efforts of cooperating with divine providence, as God actively and purposefully brought about the culmination of history.

Many Protestants saw the Reformation as the major turning point in God’s program for history. The Reformation struck a death blow to the Roman papacy, which English Protestants in particular considered to be the Antichrist. And what a mystery was revealed when America was discovered in 1492, a land hidden by providence until the very eve of the Reformation! The discovery of America and the dawn of the Reformation, occurring at roughly the same time, appeared to many Protestants as the beginning of the end of an old order. Tuveson described it this way: “Mankind might be over the hump at last. Thus the Reformation became the assurance that the long era of superstition, injustice, and poverty was ending and that light was breaking over the world. A great age of achievement had begun.”17

In the millennial view of history, as opposed to the Augustinian view, progress was the defining factor in the human experience.18 The events of Revelation were not allegories, but were literal events, taking place at a future date, but nevertheless, in real time. This notion comes through in the apostle John’s recounting of Jesus’ command to write down everything in his apocalyptic vision—“the things that you have seen, those that are and those that are to take place after this” (Revelation 1:19). If anything, Jesus seems to be referring to literal “things” to be “seen” with the eyes—things in the past, present and future time. It hardly seemed possible, especially to Protestant thinkers that we will consider shortly, that Jesus could be referring to an allegorized set of circumstances.

As the Reformation opened and developed in the sixteenth century, the New England colonies were established in the seventeenth, and the colonial wars in America culminated in the mid-eighteenth, the lines were clearly drawn. The New England Puritans (and most of English Protestantism) considered the French Roman Catholic kingdom to be the physical manifestation of the forces of the Antichrist. Specifically, the Louisbourg expedition of 1745 provided an occasion for English colonial thinkers to divide the French and English forces into those of darkness and light respectively. For example, Mark Noll pointed to William Stith of Virginia who showed “how biblical precedents”19 framed the conflicts between Britain and France. But with the rupture between the American colonies and Britain at the close of the French and Indian War in 1763 came a new conception of the division between the forces of light and darkness. From the mid-1760s through the early 1780s, Americans increasingly saw England as tyrannical, pursuing the people of the colonies as Pharaoh pursued the ancient Israelites under Moses. Ultimately, many Americans came to see their Revolution as a logical historical upward trend toward the millennial triumph from the discovery of America to the Reformation to the founding of the United States of America.

The theological roots of the tree of American exceptionalism go deeper and are more intricate than the other roots supporting it. You might say that theology is the taproot of the tree, anchoring it firmly to the ground. But exceptionalism is supported by a system of roots. Let us move on from theology and now consider the political roots of the concept of exceptionalism.

The United States originated in the Revolution as a political union of independent states. This union coalesced into a federal republic under the Constitution, which was signed in 1787 and went into effect in 1789. But the union of the thirteen original states did not emerge out of thin air. The states joined together around the common cause of independence from Britain, and that cause was undergirded by the liberal ideas expressed in the Declaration of Independence. And the ideas expressed in the Declaration had their origins even further back. The Western philosophical tradition has included liberal ideas for a long time, but for our purposes here, let us trace those liberal ideas back to England during its tempestuous seventeenth century.

The English Civil War (1642–1651) and the Glorious Revolution (1688) were two crucibles in English history that ultimately helped shape that nation into the liberal constitutional monarchy that we recognize today. The trend toward the making of England’s liberal government is long indeed, and space does not permit an extended analysis of that trend. But in the seventeenth century, things definitely came to a head. The English confronted the issue of the extent of monarchical power. Would the monarchy (read, the executive) hold the reins of power, or would the Parliament (the legislature)? Is power arbitrary, and does it rest in the hands of a divinely appointed monarch? What is the relationship between the people and their government? Does the king rule a people like a father rules his children? Or do the people delegate power to their rulers? Does power rest in an elected body of legislators, and is the monarch answerable to that body? Do the people have the right to change their government, if that government abuses its power over the people? Is government ordained by God, or does it exist by the consent of the people? And what is the proper relationship between the church and the state?

These were some of the questions contended over during the seventeenth century in England. Often those questions were dealt with on the battlefield, as at Marston Moor in 1644, Naseby in 1645 and Preston in 1648. The forces loyal to Charles I (1600–1649), known popularly as the Cavaliers, were defeated by the Puritan New Model Army under Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658). Charles I was put on trial and publicly beheaded on January 30, 1649. No one can tell the story of Charles’s execution like Will and Ariel Durant:

Prince Charles [Charles I’s son, later Charles II] dispatched from Holland a sheet bearing only his signature, and promised the judges to abide by any terms they would write over his name if they would spare his father’s life. Four nobles offered to die in Charles’ stead; they were refused. Fifty-nine judges, including Cromwell, signed the death sentence. On January 30, before a vast and horror-stricken crowd, the King went quietly to his death. His head was severed with one blow of the executioner’s axe. “There was such a groan by the thousands then present,” wrote an eyewitness, “as I never heard before and desire I may never hear again.”20

After Charles was executed, the monarchy was replaced by the Protectorate under Cromwell until just after his death. In 1660, the English monarchy was restored with the coronation of Charles II, who ruled until 1685. When Charles’s son James II ascended the throne, it was said that his desire was to return England to Roman Catholicism and rule as an absolute monarch. Parliament was in no mood to take chances with James, and the body invited William of Orange and his wife Mary (James’s Protestant daughter) to cross the Channel, land in England and replace James. The catch was that, as monarchs, they would have to recognize the supremacy of Parliament. They agreed, and landed in England with fourteen thousand soldiers on November 5, 1688. James, having little support, and thus no real ability to control events, fled for his life to France. The ascension of William and Mary to the throne in 1688 is known as the Glorious Revolution—a bloodless affair, unlike the Civil War.

John Locke (1632–1704) wrote his famous Two Treatises on Civil Government, which was published in 1690, largely to bring credibility to the actions of Parliament, particularly in inviting the rule of William and Mary. Locke said that governments ruled by the consent of the people. Rulers possessed political power, but they possessed it in trust from the people, and they maintained their power by protecting the basic rights bestowed on them by nature at birth. Thus, rulers do not have the power to rule arbitrarily. Rulers may only legitimately exercise their power in such as way as to protect the natural rights of the individual. Locke wrote, “[Power] can have no other end or measure, when in the hands of the Magistrate, but to preserve the Members of that Society in their Lives, Liberties, and Possessions; and so cannot be an Absolute, Arbitrary power over their Lives and Fortunes, which are as much as possible to be preserved.”21 Locke also penned his famous Letter Concerning Toleration, which advocated for religious toleration. According to Locke, the state only possessed power over temporal affairs. It had no jurisdiction over the individual conscience.

Events in England leading up to the Glorious Revolution led to the formation of two strong political parties oriented around the liberal ideas articulated by Locke in his Two Treatises, namely, the Tories and the Whigs. The Tories were conservatives who favored aristocratic privilege, a strong bond between ecclesiastical and civil authority, and the passive obedience of subjects to the political/ecclesiastical order. The Whigs were firmly against these positions. Their liberalism won the day in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Seventeenth-century thinkers such as John Locke, Algernon Sidney, John Milton and James Harrington articulated liberal views such as religious toleration, liberty of the press, parliamentary supremacy and rule by consent. Later thinkers, influenced by these and other earlier figures, sharpened and focused liberal ideas in the face of what they saw as overreach by George II’s prime minister, Robert Walpole, in the 1720s. In particular, John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon advocated for religious freedom and individual rights in their 1720–1723 collection of essays titled Cato’s Letters. They represented well the ideas of Real Whig ideology, a body of thought that stressed the most sweeping liberalism yet seen. Real Whig thought, as expressed by Trenchard and Gordon, was popular not only in England but also in America, especially during the 1760s and 1770s. During these years, Real Whig thought became the driving intellectual force of the Revolution. The Real Whigs took Locke’s views on toleration to their logical terminus, advocating for complete religious freedom. Religious freedom became a hallmark of the writings of Trenchard and Gordon, for example. Pauline Maier wrote of Real Whig political philosophy that “the [American] revolutionary movement takes on consistency and form only against the backdrop of English revolutionary tradition.”22 And the writings of Trenchard and Gordon were those that were among the most influential Real Whig writings on this side of the Atlantic.

How does Real Whig ideology fit into American exceptionalism? The answer is simple—it is manifested through what Mark Noll called “Christian republicanism.”23 Christian republicanism is an amalgamation of Real Whig ideology and Protestant theology occurring in American literature and rhetoric in the years leading up to and during the Revolution. The unifying themes between these two strands of thought are freedom of religious dissension, a reaction against ecclesiastical privilege and a millennialism that saw America as God’s chosen nation to bring about the final defeat of the forces of the Antichrist.

Christian republicans in America, like Jonathan Mayhew of Boston, sought to biblically justify rebellion against the mother country. Mayhew’s sermon “A Discourse Concerning Unlimited Submission,” which he gave on January 30, 1750 (the 101st anniversary of the execution of Charles I), defended the justice of the Puritans’ overthrow of Charles I. Romans 13:1-5 served as Mayhew’s text, and he preached that Charles’s overthrow was entirely just. In his letter to the Romans, Paul was not writing about submitting to a government that was evil, but a government that was a “servant for your good” (Romans 13:4). Just as it is entirely right for a child or a servant to disobey a parent or a master who rules them unjustly, a people who resist the rule of a tyrant are innocent of wrongdoing. Mayhew appealed to the principle of self-defense here—a people have the right, even the responsibility, to protect themselves against a tyrant, just as the people did in 1649 when they executed Charles I. Mayhew thundered,

A PEOPLE, really oppressed to a great degree by their sovereign, cannot well be insensible when they are so oppressed. . . . Nor would they have any reason to mourn, if some HERCULES should appear to dispatch him—For a nation thus abused to arise unanimously, and to resist their prince, even to the dethroning him, is not criminal; but a reasonable use of the means, and the only means which God has put in their power, for mutual and self-defence.24

Mayhew serves as an important figure in the years leading up to the Revolution for several reasons. First, Mayhew was a New England preacher heavily influenced by Real Whig political thought, like the idea that rulers rule by the people’s consent. Second, he was a Christian who accepted republican ideas despite the fact that, as Mark Noll has pointed out, republicanism is at odds with key aspects of Christian theological doctrine.25 And third, Mayhew, like many others in his generation, baptized Real Whig ideas in the waters of biblical theology. Mayhew is representative of a Christian republicanism that began occurring in the mid-eighteenth century, and continued into the revolutionary and early national periods. That religious brand of republicanism forms the foundation of a distinctive American civil religion, which Mayhew, along with many other figures, helped to create.

Puritan theology, Real Whig ideology and Christian republicanism are key elements in the development of the notion that America is normatively exceptional, set apart by God for a special identity and purpose. What brought these sources together to help shape this notion was the exegetical tradition of late-eighteenth-century America expressed through sermons, including jeremiadic literature. Sermons have been a powerful medium through which Americans, especially Protestant Americans, have understood who they are and what their place in the world should be. And sermons demonstrate how many, if not most, Americans have interpreted the Bible over the centuries, and read themselves and their unique story into it. Witham described this reality when he said, “To the extent that America is an idea, and owes its shape to generations of religious rhetoric, the heritage of the sermon tells the national story like no other chronicle.”26 And because of this fact, the biblical exegesis and preaching of the eighteenth century deserves consideration as a conspicuous source of civil religion in America, and thus exceptionalism.

Thus far, we have seen some hints at how Puritan theology and Real Whig ideology influenced biblical exegesis and preaching. The Puritan jeremiad is a potent example of how New England preachers interpreted the Bible and used it to their purposes. But let us consider some more specific examples of sermons in the colonial and revolutionary periods to see how exceptionalism as a concept began to take shape.

First, how was the idea of covenant expressed in colonial sermons? In 1662, Michael Wigglesworth wrote his famous poem, “God’s Controversy with New England.” The poem, an early jeremiad, starts off with a reference to Isaiah 5:4—“What could have been done more to my vineyard, that I have not done in it? wherefore, when I looked that it should bring forth grapes, brought it forth wild grapes?” Clearly, Wigglesworth meant to apply the biblical passage to his own people, even though it was originally directed at ancient Judah. With this passage, and this exegetical method in mind, it is appropriate here to quote some of Wigglesworth’s lines to see how the theme of covenant comes through so strongly, and how the Israelite covenant is shifted over to apply to New England.

Are these the men that erst at My command

Forsook their ancient seats and native soil,

To follow Me into a desert land,

Contemning all the travel and the toil,

Whose love was such to purest ordinances

As made them set at nought their fair inheritances? . . .

With whom I made a covenant of peace,

And unto whom I did most firmly plight

My faithfulness, if whilst I live I cease,

To be their Guide, their God, their full delight;

Since them with cords of love to Me I drew,

Enwrapping in My grace such as should them ensue?

If these be they, how is it that I find

Instead of holiness, carnality;

Instead of heavenly frames, an earthly mind;

For burning zeal, luke-warm indifferency;

For flaming love, key-cold dead-heartedness;

For temperance (in meat, and drink, and clothes), excess? . . .

Ah dear New England! Dearest land to me!

Which unto God has hitherto been dear—

And may’st be still more dear than formerly

If to His voice thou wilt incline thine ear.

Consider well and wisely what the rod,

Wherewith thou art from year to year chastised,

Instructeth thee: repent and turn to God,

Who will not have His nurture be despised. . . .

Cheer on, sweet souls, my heart is with you all,

And shall be with you, maugre Satan’s might.

And whereso’er this body be a thrall,

Still in New England shall be my delight.27

Notice the covenantal language Wigglesworth used here—God called the colonists of New England out of their native land and to go to a land where he would show them. He promised that he would demonstrate faithfulness and blessing to them if they would follow him and his ways. But they sinned against their God, and God was punishing them—with a drought, in this case—for departing from the covenant. But with punishment, God invites the people to repent and return to him. They are still his chosen people, and they can be restored to God and to a state of blessedness that far exceeded anything before, if they would but return to him. These themes we see repeated in the Bible again and again, but Wigglesworth presented the New England colonists as God’s covenantal people, and New England itself as the apple of God’s eye.

Next, consider how typology appeared in the exegesis of colonial sermons. Recall that typology is a common premodern approach to work out redemptive history spanning Old and New Testaments together in and through Christ. Further, premoderns traditionally used typology to cast post–New Testament events in redemptive terms. Whether any given premodern exegete followed an Augustinian or millennial view of history, the belief was always that God, by his providence, was overseeing all events to culminate in Christ’s return. Because of this, premodern biblical exegetes like those of the revolutionary period frequently saw biblical types in modern individuals and events.

One example is the 1777 sermon in East Haven, Connecticut, by Nicholas Street. In this sermon, Street defined the Americans in explicitly biblical terms. Specifically, he envisioned the Israelite exodus from Egypt as the type for the American struggle for independence from Britain. Table 1.1 supplies the subjects of this particular sermon and the typological figures Street assigned them.

In classic jeremiadic style, Street called the people of East Haven to repent from their complaining about the strife of the struggle, and to renew themselves to faithfulness to the American cause. He said, “Are you not ready to murmur against Moses and Aaron that led you out of Egypt, and to say with the people of Israel, ‘It had been better for us to serve the Egyptians, than that we should die in the wilderness’ Exod. 14.12.”28 Street’s primary argument was that God deals with his people in the same way he always has—to test them to see what is in their hearts. Street preached that just as God tried and tested his people Israel in biblical history, he is trying and testing his people in America to see if they will be faithful to him. Street’s closing exhortation is, “Let us be humble, kiss the rod and accept the punishment of our sins—repent and turn to God by an universal reformation—that God may be intreated for the land, spare his heritage, and not give it up to a reproach but restore to us our liberties as at the first, and our privileges as at the beginning.”29

Table 1.1. Comparisons in Nicholas Street’s 1777 sermon

| Biblical Figure | Typological Fulfillment |

|

Children of Israel (Exodus) Post-exilic Jews (Ezra, Nehemiah) |

American colonists |

| Moses and Aaron | Leaders of the revolution |

|

Egypt Medo-Persia Assyria |

Britain |

| Wilderness | Time of trial and testing |

|

Egyptians Sanballat (Nehemiah) Haman (Esther) |

British Tories |

| Red Sea | Military struggle |

| Canaan | Victory, freedom and blessing |

|

Pharaoh of Egypt (Exodus) Hazael of Syria (2 Kings) |

George III |

Lastly, we have considered how many colonial thinkers saw millennialism as a way to situate America’s significance in history. Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758) believed that God had hidden American shores from the eyes of civilization until such a time as to prepare it for the culmination of salvation history in Christ’s second coming. Edwards wrote, “This new world is probably now discovered, that the new and most glorious state of God’s church on earth might commence there.”30 More and more thinkers held the belief that the American colonies represented a turning point in history, and was destined to advance human civilization to the millennial reign of Christ as the eighteenth century progressed. Abraham Keteltas, preaching in 1777 to the Presbyterians in Newburyport, Massachusetts, equated the cause of America with the cause of God. America’s cause against Great Britain was the cause of liberty, justice, rule of law and individual rights—not only for those who were living, but also for those generations yet to be born.

America’s cause, for Keteltas, was the cause of good against evil. As such, it was God’s own cause. And Americans could take comfort in the fact that God will be faithful to champion the American cause because, in doing so, he was safeguarding his own cause. Keteltas did not envision the struggle with Britain as merely a political struggle. He saw it as part of the struggle of good against evil that had been going on since the fall in the Garden of Eden. Not only that, he saw the Revolution as part of the same cosmic struggle that Christ himself engaged in with the devil in his Passion. “Our cause,” wrote Keteltas, “is not only good, but it has been prudently conducted: . . . it is the cause of truth against error and falsehood; the cause of righteousness against iniquity. . . . It is the cause of reformation against popery. . . . In short, it is the cause of heaven against hell—of the kind Parent of the universe, against the prince of darkness, and the destroyer of the human race.”31

Keteltas preached this sermon from Psalm 74:22—“Arise, O God, plead thine own cause” (KJV). His sermon clearly reveals a particular exegetical method guided by millennialism. He envisioned the American colonies as being engaged in the apocalyptic struggle of the forces of Christ against the forces of the devil. Samuel Sherwood is yet another example of a preacher reading Scripture and the events of his time in this way. His 1776 sermon, “The Church’s Flight into the Wilderness,” is one of the most strikingly millenarian sermons of the time. His text was Revelation 12:14-17,32 and his exegesis is strongly typological. Sherwood’s typology, not surprisingly, is informed by millenarianism. And what is further interesting about Sherwood’s exegesis of the text is how he conflated the church with the American colonies. For instance, Sherwood preached that God brought the church into North America, a land of enormous size and bounty, and planted the church here to flourish. God, said Sherwood, “brought her as on eagles’ wings from the seat of oppression and persecution . . . nourished and protected her from the face of the serpent.”33 But Sherwood had in mind more than merely religious people of a Protestant persuasion. He had all the people of the colonies in mind when he spoke of “the Church.” Sherwood spoke of how the British civil and ecclesiastical powers had inflicted their abuses of power upon the colonies. These abuses of power were to destroy the people’s liberty and property, so that they themselves became the property of the state. Sherwood recounted the situation in this way:

Now, the administration [of the dragon, typified by Britain] seems here described, that has for a number of years, been so grievous and distressing to these colonies in America, claiming an absolute power and authority to make laws. . . . I say, the administration seems described, and appears to have many of the features . . . of the image of the beast. . . . And the language of our pusillanimous foes, and even their adherents amongst us, seems plainly predicted, Rev. xiii.4[:] “Who is like unto the beast? Who is able to make war with him[?]”34

The exegesis of colonial religious leaders, as seen in their preaching, clearly displays the theological themes found in Puritanism. And it is fascinating to see how the American premodern preaching reflects an exegetical style that has a long history dating back to the earliest centuries of church history. The sermons of the colonial period, especially those from 1763 through the end of the eighteenth century, contributed powerfully to the idea that Americans were an exceptional people in the eyes of God.

Our final root of the tree of American exceptionalism is historiography. Historiography is, broadly speaking, the study of how historians write history. Let’s keep in mind the fact of the difference between history and the past. Historians recognize that the past and history are not one and the same. The past is simply the events and persons of the days, months and years previous to the present. History is the product of those intellectual types who take the things left behind in the past and seek to make sense of them for a present-day audience. Because history is the product of human beings living in a time removed—sometimes far removed—from the past, there is a subjective element to history. And in that regard, it is important to remember historian John Fea’s admonition that all history is revisionist to some degree. Historians make use of sources and evidence that may not have been available to earlier historians studying the same subject. Fea wrote, “As new evidence emerges and historians discover new ways of bringing the past to their audiences in the present, interpretations of specific events change. This makes history an exciting and intellectually engaging discipline.”35 And if I may add to Fea’s observation, it is this fact also that can solidify a particular way of seeing the past in the minds of an entire culture, sometimes to the extent that a historian’s perspective on the past becomes a kind of orthodoxy in and of itself.

Historians of the nineteenth century who studied the origins of the United States both experienced and oversaw changes in how history itself was written. American historians writing at the end of the eighteenth century shared common backgrounds and assumptions. Figures like Mercy Otis Warren, Jeremy Belknap and Hugh Williamson were not like the professional historians we have serving in history departments at colleges and universities. These historians of the Revolution were usually wealthy elites who thought and wrote about history from a leisurely standpoint. They saw history as containing strong moral messages. They were strongly nationalistic, even though most of them wrote histories of the Revolution from a local perspective. And they generally treated the leaders of the Revolution as heroes who could do no wrong.

By the early nineteenth century, historians were becoming more and more specialized and academic. They were more interested in objectivity. They placed a higher premium on primary sources. And they saw history as a discipline separate from ethics, philosophy or theology. In other words, history was becoming a modern academic specialty in the nineteenth century. Eileen Ka-May Cheng noted that “if [antebellum] historians were in many ways even more committed than their predecessors to the nationalist function of history, they at the same time, unlike their predecessors, increasingly came to view history as an autonomous discipline.”36 This was a trend occurring in Europe as well as in America. During the antebellum period, some of the most noteworthy historians were from New England, and cast the story of America’s development as the story of New England writ large. Figures such as Edward Everett,37 Richard Hildreth, William H. Prescott and John Gorham Palfrey were part of an elite group of Bostonian historians. George Bancroft (1800–1891) was also a member of this elite group.

Bancroft was one of the most significant American historians in the nineteenth century. He wrote a ten-volume history of America from colonial foundings to the Constitution over the forty-year period between 1834 and 1874. And Bancroft was, simply put, an American exceptionalist historian. Like many Puritans before him, Bancroft saw the Reformation as a central turning point in history because through it individual liberty was introduced into the souls of common people. The American Revolution was a logical progression of the Reformation because it represented how liberty was growing and taking root in not just the religious realm, but in the economic, social and political realms also. Not only was it a logical progression from the Reformation; the Revolution was inevitable for Bancroft, because it was part of a providential plan for all human history.

Bancroft wrote his history in a context in which Americans’ confidence in themselves as a people was growing. Jack Greene wrote that Americans already saw themselves as set apart from their European cousins. They lived in a New World after all, a land of enormous promise and potential. This was a clean slate in so many ways for so many people emigrating to the American colonies from overpopulated urban centers, religious persecution, poverty and a host of other ills of a civilization set in its ways. But the notion that America was superior to other nations was new in the nineteenth century. It came about because of American independence, but also because the new nation had survived a second confrontation with Britain in the War of 1812. Although the war was not a decisive victory of America over Britain, it did prove that the republic could meet an existential threat and emerge from it intact. This view of superiority that began to prevail in the early nineteenth century formed the basis of the idea that America would serve as an example to the rest of the world in the near future. As Greene wrote, “British North America, reconstituted as the United States after 1776, would project their hopes for a better world into the future, and it would thereby make a significant contribution to the Enlightenment and its program of social and political reform.”38

Bancroft, as an exceptionalist historian writing in the tumultuous and formative years bestriding the Civil War, was a contributor to this idea of a superior America serving the world as exemplar. He conceived of nations as having a life span, much as individual persons do. Persons are born and develop through a childhood, an adolescence and an adulthood. Bancroft historian Jonathan Boyd termed this notion “organic nationalism.”39 According to Boyd, for Bancroft, “the United States no less certainly existed in embryonic form throughout the colonial period as the various parts of its body formed, grew in strength and coordination, and ultimately cut the umbilical cord from its European mothers.”40 America’s growth and development as an exceptional nation would continue, but not for its own sake. American exceptionalism pointed to what other nations could become. In that sense, there is a distinct internationalism to Bancroft’s nationalism.

Bancroft believed that God’s providence is the agent bringing all this to fruition. Bancroft, as a member of the Boston elite, was heavily influenced by the Puritanism of his forebears. He was also influenced by German idealism and the Hegelian view of history, through his intellectual upbringing at the University of Göttingen. Bancroft thought that God had indeed chosen America for a special mission in the world, to serve as an example of religious, moral and political liberty. And in doing so, God was manifesting a providential plan for all humanity, thus acting to bring human history to completion. America was the civilization that was ushering in a new chapter of human history. It was the agent of advancement, of progress. In Boyd’s words, “Bancroft’s chief end in writing the two million words of his history [was] to show one nation fulfilling its divine calling. Hence, he would argue that, although the work centers on and even glorifies America, his historiography serves a universal purpose.”41

To sum up, the ideology of American exceptionalism has a multistructured intellectual root system: theological, political, exegetical and historiographical. By the early nineteenth century, Americans largely took it for granted that their nation represented a break from the past and a decisive turn toward a future defined by progress and advancement. And millions of people emigrated to the United States in the nineteenth century to tie their own personal destinies to that of America, whose destiny seemed poised to advance from triumph to triumph.

A civil religion, with exceptionalism as one of its essential aspects, developed after the Revolution. The Declaration of Independence was one of the foundational documents in a civil religious canon that was taking shape. The Declaration made objective, transcendent, authoritative statements about the nature of humanity, the role of the government in relation to the people it represented, and God’s having established a particular order that could not be thwarted or overturned. The Declaration was followed by other documents that formed the civil religious canon: the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, Washington’s Farewell Address and others.

As the nation grew in numbers and in territorial size between the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 and the Mexican War ending in 1848, American exceptionalism divided into two articulations. One of these articulations was more strongly religious, and more certain of God’s providence concerning the future of the United States and its status alongside other nations. It was also decidedly racist. The other articulation was more agnostic concerning the providence of God, but was nonetheless certain that God had set it apart to be a moral example to the rest of the world. America could show other nations what a nation conceived in liberty might look like, how it might behave and what ideals it might pursue for the benefit, in theory if not in practice, of all humanity.

Americans struggled to figure out their place in the nineteenth century after their break with their mother country, Great Britain. They looked for their place, not only in the world doing “all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do,” as the Declaration of Independence suggested, but also their place in human history. As they struggled, they did many things that seem strange to us in the twenty-first century. William Walker is an example of such a person. But someone who most Americans have come to admire and acknowledge as the greatest president ever to hold the office—Abraham Lincoln—was motivated by the idea of American exceptionalism, as Walker was. The tree of American exceptionalism, fed by its roots, was taking its shape in the antebellum period during the nineteenth century. It continued to grow and flourish well into the twentieth and into our own century. It has yet to cease growing and developing as a civil religious idea that Americans continually look to for guidance as they try and make sense of their significance in space and time.

Bercovitch, Sacvan. The Puritan Origins of the American Self. 1975. Reprint, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011.

Gamble, Richard M. In Search of the City on a Hill: The Making and Unmaking of an American Myth. London: Continuum, 2012.

Greene, Jack P. The Intellectual Construction of America: Exceptionalism and Identity from 1492 to 1800. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

McKenna, George. The Puritan Origins of American Patriotism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

Stout, Harry S. The New England Soul: Preaching and Religious Culture in Colonial New England. 1986. Reprint, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Tuveson, Ernest Lee. Redeemer Nation: The Idea of America’s Millennial Role. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968.