The scars and foibles and contradictions of the Great do not diminish but enhance the worth and meaning of their upward struggle.

W. E. B. Du Bois, 1922

In 1922, when W. E. B. Du Bois wrote in The Crisis that Abraham Lincoln was “of illegitimate birth, poorly educated and unusually ugly, awkward, ill-dressed,” and that he was a man of profound inconsistency, “[both] despising Negroes and letting them fight and vote; protecting slavery and freeing slaves,” many of his readers took offense.1 His African American audience rightly remembered Lincoln as their great liberator, and many of Du Bois’s readers could not add nuance to their conceptions of him. A few months later, Du Bois addressed those concerned readers, calling them to seek the whole truth of the matter and not merely an imagined ideal picture of the truth. He wrote of Lincoln, “I love him not because he was perfect but because he was not and yet triumphed.”2

Open exceptionalism is an expression of patriotism like Du Bois’s expression of love for Lincoln. At the heart of what it means to be an American is the act of calling America back to faithfulness to its first principles motivated by authentic patriotism. In an open exceptionalist account of America, we affirm that America is different because it is a nation in which dissent is not only allowed; it is a virtue. Dissenting colonists in the eighteenth century, after all, birthed the nation. Open exceptionalism opens the door for citizens to acknowledge, to address and to rectify real American flaws because, in so doing, citizens express true love for country.

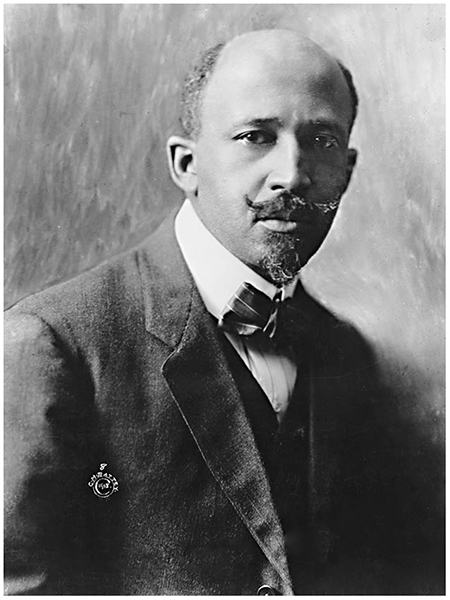

Figure 8.1. William Edward Burghardt Du Bois

We witness a clash between open and closed exceptionalism in a 1957 letter from Du Bois to Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. The State Department refused to issue Du Bois and his wife passports to travel to Ghana to attend its celebrations as a newly independent nation. This was despite the fact that the Ghanian people, led by Kwame Nkrumah, had invited the Du Boises. Not only that, Du Bois had been instrumental in establishing the Pan-African congresses that stood against European colonial rule. Du Bois wrote to Dulles to protest the situation, stating that he had committed no crimes to warrant the government’s limiting of his freedom to travel. True, Du Bois wrote, he had criticized the United States on a number of occasions. But he also gave it credit when credit was due. Du Bois challenged Dulles to be true to the American ideals of personal liberty, human dignity and self-determination. These were, in fact, ideals on which the two of them agreed when they personally met during the formation of the United Nations. Du Bois reminded Dulles,

When, Sir, in 1945 in San Francisco, I had an interview with you, we discussed the trustee provisions of the United Nations charter then in process of formation. I got from that talk an impression of your sympathy with Africa and hostility towards the colonial system. If I was right, I trust this was still your attitude and that you realize that Africa is starting forward and is asking not simply for investment in South Africa and the Belgian Congo, but recognition of black folk as human beings and citizens of a modern state. I therefore write to ask permission to visit Ghana on this occasion in response to their repeated requests, on the first day of the ninetieth year of my life.3

In this letter, we see a member of a socially rejected and persecuted minority appealing to a member of the dominant group, one who was a high-ranking officer of the American government, for justice in the name of the ideals upon which the United States was founded. Du Bois’s letter represents an act of civic engagement in the spirit of open exceptionalism—a citizen explicitly addressing a problem in American society in order to help rectify it. In this act of civic engagement, Du Bois expressed some of the highest American ideals—both in the act of writing and in the content of his writing.

We have come to the close of this book on American exceptionalism as an aspect of civil religion. In this concluding chapter, we will consider why exceptionalism as a civil religious belief matters. In short, open exceptionalist civil religion provides a basis for unity in the midst of diversity. Because of this, open exceptionalism fosters positive civic engagement by holding forth the ideals expressed in the American civil religious canon, recognizing that those ideals are always among the worthiest of goals for Americans to continually pursue within their national community.

Beyond mere national “team spirit,” American exceptionalism matters because it generates powerful assumptions in citizens’ minds about their national identity. Exceptionalist assumptions—unstated reasons people hold to justify their words and actions in the public square—entail ramifications affecting how they engage society. Furthermore, Christian people in particular have a long history of civic engagement going back to the early centuries of the church in the Roman Empire. Specifically, Christian Americans have always been engaged in culture, and indeed, Christian ideas were deeply influential (but not exclusive) in the nation’s founding.4

Many Christians assume that God chose America to be his special people to do his work in the world. Many uncritically accept patriotic expressions as a part of church worship services. Christians often sing songs linking patriotic devotion with love for God and think little about what the words mean and how those words fit into their overall theological matrix of beliefs. For many Christian people, patriotism equals spirituality because their assumption is that America is God’s country. Anyone who stands with America is, therefore, holy, good and just. Anyone who stands against America is scandalous, immoral—perhaps even demonic.

By linking the American nation with God in the ways we have seen in this book, closed American exceptionalism produces harmful assumptions leading to a form of civic engagement that divides people into groups, namely, the Chosen and the Inferior Other. Closed exceptionalism takes the ideals like federal democracy, individual freedom, equality, natural rights and government by consent and spiritualizes them, so that they become normative and binding in their uniquely American expression for all people at all times regardless of contingent factors. Closed exceptionalism breeds injustice.

Open exceptionalism is an intellectual framework that situates American ideals in history and experience. It accounts for flaws and imperfections in the American nation. Open exceptionalism does not envision a nation divided into groups, but one united around commonly held ideals applied to all and places enjoyed by all. And open exceptionalism does not conflict with Christian teaching by idealizing or idolizing the nation.

An open exceptionalist civil religion potentially brings unity out of a diverse populace. One of the ways it promotes unity is through symbols and practices. For example, Arlington National Cemetery is a powerful civil religious symbol. Arlington is a hallowed place Americans set aside for those who gave the full measure of devotion to their country, that they may rest in their graves. As you enter the grounds of the cemetery, you see signs admonishing all visitors to observe “silence and respect.” The signs are everywhere, but most visitors do not need reminding. During the height of the tourist season, you will find people from a wide variety of ethnic, linguistic, (presumably) religious and national backgrounds. You will find children, teenagers, young adults and elderly people. Many are visiting graves of loved ones, but most of them are there to see John F. Kennedy’s tomb, the Tomb of the Unknowns, and the rows of neatly laid out plots and headstones. The majority of the visitors exhibit unity through their respectful behavior, as well as their observance of the civil religious practice of visiting the cemetery. There are a host of symbols and practices in American civil religion, and vast majorities of Americans generally know and understand them and demonstrate solidarity when practicing them. Peter Gardella referred to the displays of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution at the National Archives in Washington, DC—two documents of the American “Old Testament” canon—saying that “every day, people from around the world line up—many with an attitude that resembles that of pilgrims—to visit these documents.”5 Gardella identified four values that bring coherence to civil religion: “Personal freedom . . . , political democracy, world peace, and cultural . . . tolerance.”6 While more values could be added to the list, and while not everyone agrees on the exact definitions for these values, Gardella insisted that these values “are denied by no one who claims to speak in the tradition of the United States.”7

Open exceptionalist civil religion focuses on these liberal ideas. But they are more accurately understood as values more than they are hard and fast doctrines. They are ideals that Americans perennially pursue, and often fail to attain. Nevertheless, Americans have shown themselves to be a uniquely self-examining people, with a remarkable ability to reflect on past mistakes and work to avoid repeating them. This does not mean Americans are always successful. But a strong reforming tradition historically exists among Americans, and American history can be read largely as a series of often logically connected, social, political, economic and religious reforms in the direction of human flourishing and freedom.

Gardella wrote that most Americans come to accept the open exceptionalist values of civil religion not through reason but through symbols. “They have learned to value liberty, democracy, peace, and tolerance through the monuments, texts, and images of American civil religion.”8 If Gardella is right, and I believe he is, then an open exceptionalist account of civil religion shows that Americans have much more in common than they may think—during a national election cycle, for example, or while waiting for a controversial Supreme Court decision. And such a civil religion allows religious people to practice their faith untainted by a militant, closed exceptionalist Americanism that effectually diverts attention away from the truly sacred and toward national glory, which is merely fleeting.

Perhaps the first task before Christian people, when considering what open exceptionalist civic engagement looks like, is to differentiate the church from the nation while situating the church within the national community. By doing this, Christians understand that patriotism does not equate to spirituality. By simultaneously distancing the church from the nation and placing it within the nation, Christians need not sacrifice their unique confession of faith, their loyalty to the nation or their prophetic voice when the nation acts unjustly.

One of the earliest Christian voices to situate the church in relation to the nation was the second-century apologist Justin Martyr (ca. 114–165). Justin addressed his First Apology directly to the Roman emperor Antoninus Pius (r. 138–161), to the Senate and to the Roman people. In the Apology, he sought justice for the Christians—a socially rejected and persecuted minority in the Roman Empire. Appealing to reason and good faith, Justin sought to clarify what Christians believed, dispel evil rumors about them and demonstrate their unmatched loyalty to the nation. Justin’s Apology is helpful for Christians today who confuse America with the kingdom of heaven. America is not the kingdom, and American patriotism does not equate to godly devotion. But sacrificial loyalty to the nation is not incompatible with the faith, provided that Christians follow Christ’s admonition in Mark 12:17 to “render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.”

Justin wrote that the Christians were not seeking after an earthly kingdom, but a heavenly kingdom. In this, they were following Christ’s statement to Pontius Pilate while he stood trial prior to being crucified: “My kingdom is not of this world” (John 18:36). Justin said, “If we looked for a human kingdom, we should also deny our Christ, that we might not be slain. . . . But since our thoughts are not fixed on the present, we are not concerned when men cut us off.”9 Nevertheless, Justin wrote, it was impossible for the emperor to find more loyal subjects among the Romans than the Christians. “And more than all other men are we your helpers and allies in promoting peace, seeing that we hold this view that it is alike impossible for the wicked . . . to escape the notice of God,” Justin wrote.10 In other words, Christians were the most loyal subjects of the empire, because in their subjection to the emperor they were demonstrating their subjection to God. Christians’ love for God, the greatest of duties, moved them to bow before Caesar, the civil authority established over them by God.

Christians’ loyalty to Rome, according to Justin, reached even to absurd levels, at least to human eyes. Again, love for God and obedience to Christ’s specific commands motivated this absurd loyalty. “And concerning our being patient of injuries, and ready to serve all, and free from anger, this is what [Christ] said: ‘To him that smiteth thee on the one cheek, offer also the other; and him that taketh away thy cloak or coat, forbid not. . . . And let your good works shine before men, that they, seeing them, may glorify your Father which is in heaven.’” Justin quoted Luke 6:29 and Matthew 5:16 to demonstrate the lengths Christians would go to show their loyalty to Rome. In fact, Justin told the emperor and Senate, Christians even paid the tax collectors every penny they were assessed, even when the collectors raised those taxes by extortion. “And everywhere we, more readily than all men, endeavor to pay to those appointed by you the taxes both ordinary and extraordinary as we have been taught by Him.” Still, even while the Christians went to these great extents to demonstrate their submission and loyalty to Rome, there were limits. Justin wrote, “Whence to God alone we render worship, but in other things we gladly serve you, acknowledging you as kings and rulers of men, and praying that with your kingly power you be found to possess also sound judgment.”11 In other words, God alone was due worship and first-order love and obedience; yet Caesar was God’s established ruler over all things of a civil nature for the Christians.

Thus, Justin situated the church within the Roman imperial order. No one was more devoted to the flourishing of Roman society than the Christians. No one served the emperor more faithfully and with more subservience than the Christians. The Christians even paid extorted tax monies in the spirit of Christ’s teaching: “Him that taketh away thy cloak forbid not to take thy coat also” (Luke 6:29 KJV). And even though the Romans persecuted the Christians, Justin wrote, the Christians were committed to love their persecutors. “And of our love to all, [Christ] taught thus: ‘If ye love them that love you, what new thing do ye? for even fornicators do this. But I say unto you, Pray for your enemies, and love them that hate you, and bless them that curse you, and pray for them that despitefully use you.’”12 And yet, Justin reminded his hearers, Christians worshiped neither Rome nor its emperor, but God alone. “But just so much power have rulers who esteem opinion more than truth, as robbers have in a desert. And that you will not succeed is declared by the Word, than whom, after God who begat [Christ], we know there is no ruler more kingly and just,” wrote Justin.13 Here he insisted that Rome’s persecution of the Christians would not succeed in blotting them out. Rome’s rulers, in unjustly pursuing the Christians, were destined by God to fail in their attempts because they were also under the rule of God. Justin said, “If you pay no regard to our prayers and frank explanations, we shall suffer no loss, since we believe . . . that every man will suffer punishment in eternal fire according to the merit of his deed, and will render account according to the power he has received from God.”14

An open exceptionalist civil religion affirms how Justin situated the church within the nation. The church and the nation are distinct. While the civil leaders are established by God (see Romans 13:1-5), they are not flawless. While the nation is devoted to high ideals like religious freedom, the nation is not morally regenerate. This conception of the nation cannot be styled, “America, right or wrong” or “America, love it or leave it.” Authentic patriotism—taking the form of sacrificial devotion and love for the national community—is entirely appropriate. But when the nation offends justice, then the church must find its prophetic voice and call the nation to amend its ways. Martin Luther King Jr. was such a prophet. So was W. E. B. Du Bois.

Du Bois was one of the most prolific writers and profound thinkers in American history. His thought and writings cover a multitude of topics, and he conducted his ideas through a variety of literary genres such as history, fiction and poetry. I like to refer to Du Bois as a black Aristotle, because like the ancient tutor of Alexander, his thought and writings are so ample, innovative and profound. He lived into his nineties, and few lived a richer, more productive life. His voice rang through the America of Jim Crow and inspired millions of blacks to stand against the innumerable limitations, injuries and indignities placed upon them by official American persecution. In fact, Du Bois’s voice is, in many ways, like Justin’s. Like Justin, Du Bois was a member of a persecuted minority. Like Justin, Du Bois appealed to a Christian ethic in his plea for justice. Like Justin, Du Bois warned a racist American society that God would not abide wickedness forever. And like Justin, Du Bois exposed false Christianity and explained true Christianity to those hypocritical ones professing the faith but refusing to live by the faith. Just as Justin wrote to Emperor Antoninus Pius, Du Bois wrote to President Woodrow Wilson in 1913, “We want to be treated as men. . . . We want lynching stopped. We want no longer to be herded as cattle on street cars and railroads.” Further, he appealed to the best of American ideals in his letter to Wilson in behalf of African Americans chafing under institutional racism: “In the name of that common country for which your fathers and ours have bled and toiled, be not untrue, President Wilson, to the highest ideals of American Democracy.”15 Note that Du Bois emphasized that it was not whites alone who sacrificed all for the nation. African Americans had borne the burden for liberty alongside whites; they had earned their rightful place as equally valuable and acknowledged citizens in American polity and society.

Du Bois has been characterized by many historians as irreligious, or even anti-Christian. Nothing could be further from the truth. Edward J. Blum demonstrated this fact in his religious biography of Du Bois, subtitled American Prophet. Describing the presence of religion in Du Bois’s life and writings, Blum said it was “ubiquitous.” Blum wrote, “Du Bois was an American prophet; he was a moral historian, a visionary sociologist, a literary theologian, and a mythological hero with a black face.” By the end of his life in 1963, Blum said, “Du Bois became a rogue saint and a dark monk to preach the good news of racial brotherhood, economic cooperation, and peace on earth.”16

But Du Bois was not a Christian according to the pattern of early to mid-twentieth-century Christianity, defined as it was in America by a white culture that systematically oppressed him and his race. Christianity, as defined by whites, was a perversion of true Christianity because it was built on racial hubris. Du Bois said that “white Christianity is a miserable failure” because, in its racial superiority over African Americans, whites “denied Christ” by “claiming super-humanity” and consistently “scoff endlessly at our shortcomings.”17 In contrast, African Americans embodied the truest form of Christian ethics as they bore up under institutionalized racism. Concerning faithfulness to the teachings of Christ and the Golden Rule, Du Bois said, “In these matters the American black man occupies a singular place . . . [in that] he himself as a group exemplifies Christian ethics to an astonishing degree; he represents the meek and the lowly; he has been ‘slow to wrath and plenteous in mercy.’ He has attempted . . . to forgive his enemies and turn the other cheek.”18 In holding out African Americans’ faithfulness to Christ’s ethical standards to the persecuting majority, Du Bois reads much like Justin, who advocated for the Christians in Rome during the second century in similar ways.

Du Bois eloquently described some of his most cherished convictions at the beginning of his work Darkwater, published in 1920. In his “Credo,” Du Bois explained his vision of justice and brotherhood of all humanity, regardless of artificial racial distinctions. He wrote, “I believe in God who made of one blood all nations that on earth do dwell. I believe that all men, black and brown and white, are brothers, varying through time and opportunity, in form and gift and feature, but differing in no essential particular, and alike in soul and the possibility of infinite development.”19

This belief animated his belief in the sinfulness of racist America in the early and mid-twentieth century. In Dusk of Dawn, Du Bois inserted a fictional character to illustrate and explain this racism. Du Bois’s character is a white man of stature in American society—an Episcopalian, a Republican, an opera enthusiast, a member of the American Legion, with a host of other associations. And he is middle-aged, married, making an income of $10,000 per year. His pastor, the Reverend J. Simpson Stodges, DD,

preaches to him Sundays (except July, August, and September) a doctrine that sounds like this . . . : Peace on Earth is the message of Christ, the Divine leader of men; that this means Good Will to all human beings; that it means Freedom, Toleration of the mistakes, sins, and shortcomings of not only your friends but of your enemies. That the Golden Rule of Christianity is to treat others as you want to be treated, and that finally you should be willing to sacrifice your comfort, your convenience, your wealth, and even your life for mankind.20

Rev. Stodges’s preaching sounds good, until he tells the man that, since “we can’t always attain the heights, much less live in their rarefied atmosphere,” then the thing to do was to “at least live like a Gentleman with the ‘G’ capitalized.”21

Since the preacher taught that the Christian moral system was entirely unattainable, and thus futile, the logic brought the upstanding man from “Christian” to “Gentleman.” As a “Gentleman,” he is concerned about his country’s standing on the international scene, especially during the conflagration of World War I in Europe. Concern for America logically entails a further progression from “Gentleman” to “American.” As an “American,” the man believes he is to support the country no matter what, “thick and thin,” and that America “must sit among the great powers of the earth.” America should be considered by other nations “as a sort of super-power, umpire of humanity, tremendous, irresistible.”22 From these hyperpatriotic sentiments, logic brought the man to the final stage of “White Man.” As “White Man,” he realized that “his whiteness was fraught with tremendous responsibilities” and that “colored folks were a threat to the world. They were going to overthrow white folk by sheer weight of numbers, destroy their homes and marry their daughters.”23 As “White Man,” the man’s attitudes toward the world were defined by “War, Hate, Suspicion and Exploitation.”24

Each stage of mental, spiritual and emotional development in this man—Christian, Gentleman, American and White Man—was defined by a set of codes. In table 8.1 we see how the progression of stages logically took shape along with their corresponding codes.

Table 8.1. Character development in Du Bois’s Dusk of Dawn

| Christian | Gentleman | American | White Man |

| Peace | Justice | Defense | War |

| Good Will | Manners | Caste | Hate |

| Golden Rule | Exclusiveness | Propaganda | Suspicion |

| Liberty | Policy | Patriotism | Exploitation |

| Poverty | Wealth | Power | Empire |

In Du Bois’s fictional story of the white man’s progression from Christianity to militant white supremacy, we see a progression from Christianity to closed American exceptionalism. But we must understand Du Bois’s warning. First, it is important to note carefully that Du Bois was not saying that Christianity per se leads to closed exceptionalism. Recall that Rev. Stodges preached a good message, but divorced his message from reality in his conversation with the man. The Christian message, for Stodges, was an impossible ideal, a futile aspiration. The best anyone could hope for, according to Stodges, was to live like a gentleman. So, the white supremacy of closed American exceptionalism logically flowed not from the Christian ethic but from the denial of its truth and power in favor of something counterfeit. Thus, from this counterfeit ethic logically flowed the white supremacy of closed exceptionalism.

Many Christians today, in their conflation of the Christian message with Americanism resulting in closed exceptionalism, exhibit similar patterns of thought. They hear Christianity taught and preached. They read the gospel in their Bibles. But many professing Christians wave off the Christian ethic with sayings like, “Christians aren’t perfect, just forgiven.” Or, they envision God as an American, who continually reminds his chosen nation that “if my people who are called by name humble themselves, and pray and seek my face and turn from their wicked ways, then I will hear from heaven and will forgive their sin and heal their land” (2 Chronicles 7:14). And they take Christ’s words to his disciples, which he gave to them in the upper room the night of his betrayal to explain the meaning of his impending death—“Greater love has no one than this, that someone lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:13)—and apply them particularly to American soldiers dying in battle.

The problem with these, and many other Americanized distortions of the gospel, is not that they are patently false. There is some truth to each of these platitudes. But if we honestly evaluate them biblically, these platitudes amount to a counterfeit, Americanized Christianity. They lead well-meaning Christian people down a path to closed American exceptionalism, and to potential for wrong in the name of right.

Du Bois, in the style of a prophet, warned Americans of this downward progression in Dusk of Dawn and a host of other writings. While the rock bottom of this progression was militant white supremacy, a key step was closed exceptionalism, the idea that America was always right and must be defended and justified at all costs. The irony of Du Bois was that even though he was not, strictly speaking, an orthodox evangelical Protestant, he had a better understanding of the disconnect between the Christian gospel and exceptionalist religious nationalism than many, if not most, church people of his day. Blum put it this way: “The supposedly irreligious Du Bois seemed to have more faith in the social power of Christianity than many of its proclaimed believers.”25

Juxtaposing Justin and Du Bois in an attempt to build an open American exceptionalist model for civic engagement may seem strange. They lived seventeen centuries apart and in vastly different historical situations. But both were members of a persecuted minority. Both voiced messages of justice, brotherhood and freedom. Both sought to capture the meaning of the Christian ethic and apply that ethic to the public square. And both Justin and Du Bois registered dissenting voices from the respective majorities of their times. In these ways, they model an open exceptionalist civic engagement that was edifying and enduring. Dissent in the direction of just reform is squarely within the American civic tradition. Many of the most dedicated American patriots were those who raised their voices to call their country back to the liberal ideals at the basis of the nation’s founding. Many of those patriots were professing Christians, although they represented a variety of denominational, confessional and practical differences. But the open exceptionalist model for civic engagement tends toward justice—where every person receives their due, and where each is afforded the dignity they deserve as being created in the image of God.

Ronald Reagan, when he spoke to the National Association of Evangelicals in Orlando, Florida, in 1983, was best remembered for calling the Soviet Union an “evil empire.” In fact, most people may not remember anything about that speech except that particular reference. In reality, Reagan spoke about a variety of issues, and he did not get to the Soviet “evil empire” until close to the conclusion of the speech. For instance, he spoke about the injustice of abortion, saying “until it can be proven that the unborn child is not a living entity, then its right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness must be protected.”26 He also spoke about the injustice of racism, particularly in the churches. He urged the gathered clergy in attendance to “use the mighty voice of your pulpits and the powerful standing of your churches to denounce and isolate these hate groups in our midst. The commandment given us is clear and simple: ‘Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.’”27 Interestingly, Reagan used a line from a document in the American civil religious canon and a reference from the Bible to extol not just an American, but a human, ideal: the dignity of every human soul. Du Bois often used the same method to emphasize the same ideal. In this way, perhaps Reagan and Du Bois—two figures not often associated together—are alike in important ways. To be sure, Reagan and Du Bois would have parted ways on many, if not most, social, economic and political issues. But on the broad values of American civil religion, especially as Gardella identified them—liberty, democracy, world peace and cultural tolerance—there is likely more common ground between them than not. As Du Bois would likely have heartily agreed with Reagan’s words on basic human dignity for the defenseless and oppressed, Reagan would likely have resonated with this prayer on humility from Du Bois. May it be so for each of us.

May the Lord give us both the honesty and strength to look our own faults squarely in the face and not ever continue to excuse or minimize them, while they grow. Grant us that wide view of ourselves which our neighbors possess, or better the highest view of infinite justice and goodness and efficiency. In that great white light let us see the littleness and narrowness of our souls and the deeds of our days, and then forthwith begin their betterment. Only thus shall we broaden out of the vicious circle of our own admiration into the greater commendation of God. Amen.28

Blum, Edward J. W. E. B. Du Bois: American Prophet. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007.

Du Bois, W. E. B. W. E. B. Du Bois: Writings. Edited by Nathan Huggins. New York: Library of America, 1986.

Hawkins, J. Russell, and Phillip Luke Sinitiere. Christians and the Color Line: Race and Religion After “Divided by Faith.” Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Sommer, Carl J. We Look for a Kingdom: The Everyday Lives of the Early Christians. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2007.

Tocqueville, Alexis de. Democracy in America. With an introduction by Alan Ryan. New York: Knopf, 1994.