Jesus versus the Warrior Spirits

Sorcery faded into the background for many weeks, overshadowed by attention to the rice fields and the demands of everyday life. As the rains diminished in May and June, hunting picked up. Men returned from the forest burdened with peccary, armadillo, game birds, and the occasional monkey. Huascayacu’s passionless flirtation with Christianity continued, sustained by prayer meetings on Sunday mornings.

Two young men, Jaime and Samuel, led services when Tomás was away. They read Bible passages and taught the congregation songs from the Wycliffe Bible Translators’ hymnal. They encouraged children to mime the lyrics by pointing to heaven or stamping their feet as they marched to Jesus. “I reject sin. It’s bad, bad,” a favorite hymn declared. “God’s path is a good path, better, better. This path goes to heaven.” The two earnest converts—youths awkwardly trying on adult gravitas for size—quizzed the adults to make sure they understood the sermon about sin and forgiveness. What the small congregation thought or felt during the services was hard to gauge. As much as anything, they seemed to be there because Christianity was modern, even if they never talked about it in those terms. “God, Apajuí, helps us to think better,” people would say. There was a genuine feeling that something in their lives was changing, had to change. The destination of the change remained indistinct.

Then witchcraft elbowed its way to center stage again, this time in another community that bordered the Marginal Highway. News came first in trickles and then as a flood, each story adding lurid details.

A prominent senior man, head of a large household, collapsed and died suddenly. The symptoms described by witnesses suggested catastrophic stroke or cerebral aneurysm. For the surviving kin, the abrupt death of a vigorous, middle-aged man was no mystery: the cause had to be sorcery—spiritual murder. The only mystery was the identity of the perpetrator.

Relatives of the dead man prevailed upon a kinsman named Genaro, the Alto Mayo’s most active shaman, to take yáji, the potent hallucinogenic brew used by healers throughout much of the western Amazon. They hoped that Genaro’s shamanic vision would reveal the killer’s face. It did. The secret sorcerer, Genaro said, was Pedro, a teenage visitor from the Río Potro area. Pedro’s remote home community had no school, and he was living with relatives in the Alto Mayo to complete his primary education. Enraged by what they saw as an unforgivable betrayal of trust, several of the deceased man’s kinsmen vowed to take Pedro’s life.

Pedro’s local kin hustled him onto a truck headed out of the region. Genaro and three other men got wind of the escape and set off in pursuit. In their own hired truck, the posse managed to overtake the vehicle in which Pedro was a passenger. Somehow they convinced Pedro’s driver that the young man had to return with them so that a problem could be sorted out back in the village. Whether Pedro went with them willingly was never made clear. The pursuers took him into the forest not far from the highway, disemboweled him with knives until he bled to death, and buried his remains nearby.

The immediate dilemma for the teachers was whether the killing should be reported to the authorities. The region’s police investigators were not known for nuance or a willingness to get under the skin of a case involving exotic understandings of guilt and innocence. It seemed likely that they would arrive in force and arrest the wrong people. If the body remained hidden, there might not even be a prosecutable case.

A teacher close to the case eventually sought my advice. Should he report the murder? Would I be willing to do it instead? His request potentially drew me into the matter. It was, on the face of it, a classical dilemma of fieldwork ethics. But to my way of thinking, the specific circumstances settled the ethical question. I had little relevant knowledge. I was privy only to hearsay several steps removed from events. And I shared the Awajún’s skepticism about the ability of Peruvian police and courts to sort out the crime in a way that would be just. In the end, the police were never informed of the killing. Everyone awaited an eventual settling of accounts by other means.

Later, when I came to know the men involved and was forced to witness and, to a limited extent, share their fear of reprisal, the full human dimensions of the affair became hauntingly clear. But at that moment, distanced from it by twenty-five miles of rainforest, rice fields, and derisory roads, it felt abstract, like news of an earthquake on the other side of the planet.

Talk of witchcraft elsewhere revived similar fears in Huascayacu. Soledad, a recently divorced mother whose parents had abandoned the village for other parts, said without hesitation that sorcery was the cause of their departure. The sorcerer in question was Tiwijám, one of Eladio’s sons. Tiwijám, she said, was responsible for the illness of her mother, her uncle, and other members of the family. She revealed this while showing me her father’s abandoned house. Beams of sunlight, slanting in through the palm-slat walls, illuminated the dusty air. Well-made baskets and fish traps still hung from the crossbeams. On the dirt floor stood beer pots and two handsome chimpuí, carved hardwood stools used only by men. The house also warehoused rusted car parts, fragments of electrical equipment, a battered suitcase, and a dog-eared set of playing cards with pictures of naked women on the back. Soledad’s eccentric father, Utiját, was known as a packrat. Why he had carried heavy car parts to a house miles from the nearest road was a mystery. Most likely he planned to salvage the metal for a quirky project of one sort or another.

In many societies, witchcraft accusations are commonly leveled at individuals who are socially marginal or deviant in some way. Tiwijám proved an unlikely target on those grounds. He was average almost to a fault. He lacked his brother Kayáp’s good looks and ebullience but was just as hospitable. He got on well with his wife, Simira, and was a dutiful guardian to two children fathered by Simira’s first husband, Tii, prior to the latter’s murder nearly a decade earlier. He and Simira had lost their share of infants to unknown illnesses. He was neither richer nor poorer than anyone else in Huascayacu.

What made him the focus of suspicion was a healing session he had attended some years before. It was conducted by Genaro, the same healer implicated in the recent murder. While in his trance, Genaro, accompanied by two less experienced iwishín, inspected Tiwijám’s body and found tiny, glowing tséntsak or sorcery darts. These darts can be used to kill or to heal. Genaro reported that Tiwijám’s chest, neck, and mouth were full of darts. They were also visible from his shoulders to his elbows. Genaro sucked one out—a tiny colored ball that he called a killing bead—to confirm their presence. When the darts reached Tiwijám’s fingertips, Genaro said, he would become a full-fledged killing sorcerer. His only hope was to begin the arduous process of domesticating this power through months of fasting, constant consumption of hallucinogens, and apprenticeship to a healer.

Villagers speculated about how Tiwijám had come to harbor these darts. Some people proposed that they had been planted there years ago without his knowledge, perhaps as he slept, by a witch named Chamikán, now dead. Others held that the source was a woman named Puwái, who prior to her suicide may have been given darts by her iwishín husband. Still others claimed that Tiwijám had actively sought them on his own. Whatever the original source, Tiwijám had been marked as a man with hidden killing power that he needed to discipline and bring into the light of public scrutiny. But he was unwilling. He hadn’t the heart for it, he said. The path of the iwishín was too hard, too full of deprivation and danger.

Later Tiwijám went to another iwishín to see whether Genaro’s judgment would be overturned. This iwishín told Tiwijám that he detected no darts but later informed others in secret that Tiwijám was a hidden sorcerer.

This legacy of suspicion erupted in bitter recriminations after Tíwi and one of his wives, Chapáik, took their gravely ill infant son to an iwishín named Táki in the community of Dorado and returned days later with the lifeless baby in their arms. A paramedic had earlier diagnosed the child’s illness as anemia, but the medicine he prescribed did little good. Táki took yáji and, once his visions began to intensify, discerned that the real cause of the child’s illness was sorcery. “Táki saw that the baby’s stomach was filled with something black, like dark clay or pitch,” Tíwi said to those gathered in his house. “This black clay is hard to cure. It makes the victim’s stomach become bloated until it explodes.” They fed the baby mashed gingerroot in water to make it vomit or defecate the substance revealed in Táki’s vision. In the baby’s feces the iwishín found small pieces of clay, bits of something that looked like rice husk, and fragments of the rough bark of a manioc tuber. This was sorcery, he confirmed. For those who crowded around him in Huascayacu, Tíwi unwrapped a small banana-leaf packet. Inside lay the incriminating evidence. To me it looked fresh, undigested. Tíwi also showed us a lock of the dead baby’s hair.

While Tíwi spoke, Chapáik mourned in the odd, singsong keening voice that greeted death among the Awajún. Little children cried in the same distinctive style by the time they could walk. Chapáik would wail, clap her hands softly, and then suddenly break off to add detail to Tíwi’s account in a normal speaking voice.

Complicating the drama was news that in a nearby house, Tíwi’s daughter Hermina claimed to have taken poison because she was distraught over her half sibling’s death. Hermina was a slip of a girl, perhaps fourteen. Sitting on a bench with Margarita, an aunt, she was surrounded by agemates and younger children who watched her with curiosity. Her eyes were red-rimmed and she was spitting frequently. Otherwise, she looked unaffected by whatever she had swallowed. Despite the apparent seriousness of the situation, there was a fair amount of laughing and joking. When Tíwi came to find out what was going on, he thought he saw green leafy matter on her teeth and gums—possibly the poison tsúim, although now Hermina denied having eaten any. Tomás said he was certain that Hermina would die because she had tried to kill herself before. She had swallowed laundry detergent with the improbable English name of Ace, which in Spanish and Awajún is pronounced with two syllables. That attempt had been provoked by an argument with her mother. She was saved that time, Tomás said, but surely she would die now.

There was no ipecac in my medical kit, but I had some mustard that when mixed with warm water might induce Hermina to vomit whatever she had swallowed. Returning with the mustard water, I met two teenage boys coming down the path, laughing and mocking Chapáik’s weeping. The atmosphere was festive except in the house of the grieving parents.

Hermina first refused to drink the mustard water but finally agreed after being chided by her father. She swallowed a bowlful. Then she moved to a bed and began to pull her clothes and other small personal items out of a waterproof basket. Tomás pronounced this to be another sign of her imminent death: “She’s looking at her possessions. She’ll die soon.” Hermina began to tear the better of her two dresses into shreds, to general laughter. Soon she was laughing, too, as she sat on a bed with other girls. She drank more mustard water and finally went outside to vomit, with others trailing behind to watch the spectacle. The two young men who had led the prayer service tried to convince her that God was offended by suicide and that she shouldn’t try it again. She said that she had chewed part of a tsúim leaf but hadn’t swallowed much. There were no signs of poisoning.

Back in his own house, Tíwi announced that there was too much witchcraft in Huascayacu and that he intended to move to another community as soon as he could plant a garden and build a house there. As he spoke, Tiwijám was spotted walking our way. There was soft tittering from those who considered Tiwijám the source of the witchcraft.

On Sunday, five days later, Eladio convened a village meeting. After a brief Christian service, Tomás spoke of the need to complete construction of the new school as soon as possible. It was also important, he said, for the men of the village to build a palm-wood jail that would be used to punish people who shirked communal work or offended community sensibilities. Discussion then shifted to the sorcery problem. Tíwi was leaving; Utiját, Wayách, and Arturo had already abandoned their houses and fields. If things carried on like this, Tomás said, eventually everyone would move away and the community would cease to exist. Referring to Tiwijám by implication but not by name, Tomás said, “Genaro saw a witch here while another iwishín, old Táki, could see nothing. How can this be if a curer sees the truth? The way to settle this is to bring a third iwishín to look at everyone in the village and find the witch.” He proposed inviting a mestizo shaman from Rioja, the brother-in-law of an Awajún woman. “If the shaman finds a witch among the men, he’ll be forced to leave. If it’s a woman, she’ll be punished. We’ll cut her ear.”

People began to argue about Tomás’s proposal. Tiwijám, obviously fighting for his reputation and perhaps his life, was prominent in the exchanges. He defended himself vigorously, but his face was etched by worry. Tíwi, Katán, and others dredged up quarrels and unexplained deaths dating back a decade or more. I could understand the discussion only imperfectly because so many people were shouting at the same time. After an hour of accusations and rejoinders, everyone drifted away. Nothing had been settled.

This noisy discord might suggest that the village was always an unhappy place. But the conflict remained puzzlingly episodic. Once the ill feeling had been aired, it dissipated for a time. Tíwi was determined to join the exodus from Huascayacu, but his departure would take months to complete. There were crops for his wives to harvest in their present location, fields to clear and plant in the new one. There was the rhythm of the school year to contend with. After a good day’s hunting, men still invited other households to join them for plates of meat and boiled manioc. Beer parties—less frequent in the dry season than they had been during the rains—continued to be convivial affairs that drew in most members of the community.

Schoolboys learning to march, Huascayacu, 1977.

Photograph courtesy of Michael F. Brown.

At the six-month mark, I was joined in the field by Margaret Van Bolt, whom I had met in the graduate program of my university. A lanky, soft-spoken midwesterner, Margaret had effortlessly aced the department’s most challenging courses. But she eventually tired of academic theorizing that struck her as pretentious and detached from real life. After completing a master’s degree in anthropology, she left the program to develop her talent for scientific illustration, a skill in great demand at the university. She was also an accomplished photographer. As a couple, we had been through ups and downs. Her visit seemed like a way to clarify a relationship unlikely to survive two years of complete separation.

Margaret’s abrupt immersion into the life of an indigenous village in the Upper Amazon must have been a profound shock, yet she adapted to its challenges with good humor, staying far longer than either of us expected. Unburdened by pressure to complete a degree, she was free to focus her attention on things that genuinely interested her. Over the following weeks and months she pieced together the genealogy of Alto Mayo families, eventually achieving knowledge of their family lines that surpassed their own. She made pots with women and learned how to make passable manioc beer. Once she got the hang of the language, she was able to talk to women about fertility, garden magic, and dealing with husbands, matters that were mostly off-limits to me. During her time in the Alto Mayo Margaret was the object of courtly treatment by men and unfailing kindness by their wives and daughters.

The arrival of my compañera was the talk of Huascayacu for days. It was rare for a man to live alone in Awajún society. Gender roles were rigid: men did not cook, make or serve beer, work in manioc gardens, or wash clothes when they could possibly avoid it. That meant that single men felt obliged to attach themselves to a household that included at least one adult woman. I had dealt with this by taking meals with Tomás’s family and washing my own clothes as discreetly as possible—not that I had enough privacy to keep anything secret for long. Single men were also presumed to be sexual predators. I had adhered to the code of propriety laid out by Tomás months earlier, to the point that some men began to pity me because of my celibate condition. Kayáp was once moved to give me a late-night tutorial on how to seduce Soledad, the appealing divorcée whose unattached status provoked great interest among Huascayacu’s men. It was an amusing lesson in Awajún courtship technique but not one I was prepared to put into practice.

If Margaret’s arrival had a normalizing effect, it was only temporary. Within days, people wanted to know why we didn’t have children. A typical Awajún woman in her mid-twenties would already have had as many as a half dozen pregnancies and, accounting for miscarriages and the high rate of infant mortality, perhaps three children in tow. Our childlessness served as a wearisome talking point for months.

Setting up an autonomous household created new complications. We had to carry a small kerosene cookstove to Huascayacu and provision it with fuel, still scarce in the region. Securing food became a burdensome chore. We were able to supplement canned foods with eggs, peanuts, manioc, plantains, and maize purchased from our neighbors. I packed in blocks of locally made brown sugar, called chancaca, for breakfast oatmeal. Chancaca, boiled down from pressed sugar cane in huge outdoor pots, contained so many honeybee parts and bits of other insects that it may, in fact, have been a significant source of dietary protein. A small kitchen garden produced occasional tomatoes as well as radishes of near-Jurassic immensity. The shotgun shells that I distributed to hunters ensured that we were regularly invited to meals with game meat, although Margaret never acquired a taste for monkey, armadillo, wasp larvae, and other Amazonian foods that I had learned to eat in order to survive.

Several government agencies had proposed meeting with Awajún leaders in Shimpiyacu, a remote community with one of the largest land grants of the Alto Mayo. Two boatloads of officials were to travel upriver from Moyobamba, but from Huascayacu travel to the meeting required a day and a half’s hike through the forest. On the day of departure, Margaret and I joined Eladio, Kayáp, Oscar, Tomás, and two youths on a path leading out of the village. The muddy trail sucked at our feet. Streams swollen by recent rains could only be crossed by balancing on bridges made of a single slender log, which in one case lay under several inches of fast-moving water. As Oscar walked ahead to scout for game, Eladio pointed out overgrown gardens and house sites abandoned years before. We saw a white capuchin monkey, a game bird called Spix’s guan much favored by hunters, and a pair of collared peccaries. The guan and one of the peccaries were shot by Tomás and Oscar, which lifted everyone’s mood.

We made camp near a stream about an hour before dark. With great economy of motion, Kayáp and one of the young men threw together two simple shelter frames—one large, one small—and then roofed them with leaves of a palm called tuntúam. Leaves from a different species of palm, shímpi, served as ground cover. Oscar started a fire, singed the hair off the peccary he had killed, and then carved it into chunks suitable for grilling. He spitted the liver on a stick and set it over the coals. As the meat cooked, the young men talked about their romantic prospects in Shimpiyacu. Eating was serious business, though, and conversation ceased until everyone was sated by the meat.

We broke camp the next day two hours after dawn. Crossing a stream called Sukiyacu, “testicle river,” Eladio explained that the name came from a painful accident involving a man who lost his footing and made a hard landing astride a log bridge. By midmorning, there were signs of human presence—an abandoned camp, the ruins of an old house—and the pace increased. Before approaching the first occupied house, the men spruced up next to a small stream. They washed their face and hands, donned clean clothes that had been carried in waterproof baskets, and carefully combed their hair. With red achiote paste, Kayáp and Eladio painted thick stripes under their eyes. The goal was to make a good impression. Unfortunately for Huascayacu’s reputation, the pair of kirínku attached to the delegation were too mud-spattered and bedraggled to meet the prevailing standard of personal grooming.

Shimpiyacu had a population almost double that of Huascayacu and was more conservative. Some men still wore itípak, the cotton kilts that had been abandoned in Huascayacu in favor of trousers. Houses were built in the traditional oval style and on a grand scale. We were given use of a sleeping platform in the house of a man named Chumpík, whose wife immediately fed us manioc and boiled howler monkey. As the food was being served, Chumpík spoke of life in Shimpiyacu. In response to a question about whether the community had an iwishín, a curer, he responded, “No, we get along here. We don’t have a problem with sorcery.” This observation, shared almost as an aside, was an instant lesson on the ambivalent moral status of iwishín, whose training and healing activities serve as daily reminders of the ubiquity of sorcerers.

A slight disfigurement of Chumpík’s nose marked him as someone afflicted by leishmaniasis, a disease spread by a species of biting fly. Leishmaniasis typically appears first as a skin lesion and then enters a chronic phase that attacks tissue in the nose and throat. In the most advanced form of the disease, a victim’s nose may be completely destroyed, leaving only a gaping hole. Various drugs can cure leishmaniasis, but treatment must continue over weeks or months, a requirement rarely satisfied by patients who live far from medical posts and pharmacies.

Conversation with Chumpík was interrupted by news that the government dignitaries had arrived. There was bedlam on the riverbank as men from the Ministries of Agriculture, Health, Nutrition, and Education, as well as the Civil Guards and the Forestry Police, were greeted by the community’s ápu and teachers. The visitors unloaded their gear from two boats under the watchful eye of scores of Awajún, young and old. I recognized the Civil Guard officer, Ensign Quiróz, from a previous friendly encounter in Moyobamba. Today he was dressed in a Jungle Jim ensemble, complete with camo jacket, Australian bush hat, knee-high boots, and sidearm.

The guests were taken to a house that the community had built to accommodate them. We joined them for dinner. Their conversation was spiced with tidbits of jungle lore, mostly fallacious. They badgered the teachers for useful Awajún words that they then massacred through mispronunciation or inappropriate use. Ensign Quiróz walked about the village saying “Pégkeg pujájai,” “I’m fine,” to everyone he met and was puzzled when he got no response. It probably didn’t help that he addressed men as “sister” in their language.

The nights at Chumpík’s were among the first that I spent in an occupied Awajún house because Huascayacu had provided me with my own. The experience offered nothing like the Western ideal of a good night’s sleep. Young children nodded off not long after dark and their parents soon afterward. The sounds of barking dogs, crying babies, or young revelers returning from social visits elsewhere punctuated the night. At about 3:00 A.M., Chumpík’s wife, Mamái, peeled manioc tubers and set them to boil. As they awoke during the night, people could be heard talking quietly on their sleeping platforms. Some arose and fanned the fire back to life so that they could warm themselves. At dawn, Mamái brought bowls of warm water that men used to rinse out their mouths. She followed this with warm manioc beer and, later, food.

The quiet bustle of the morning was interrupted by an explosive thump upriver. The officer for the Forest Police, whose job was to educate the Awajún about the nation’s conservation laws, was apparently using dynamite to fish in the Río Huascayacu.

After this diversion, blasts from a snail-shell trumpet announced the day’s first session. Ápus and teachers from several neighboring communities were in attendance, as were perhaps eighty other Awajún men and women. Through an interpreter Ensign Quiróz reminded them that they were not allowed to steal, beat their wives, or kill one another. Everyone should obey the orders of the community’s ápu. Communities were permitted to construct a jail, a calabozo, if they wanted to. They could exile troublemakers. But violent crimes were to be dealt with by the police, not the community.

While Quiróz and other officials spoke to the assembled men, a doctor gave a talk on public health to a large group of Awajún women. His remarks focused on child care and sanitation. He urged women to wash their babies daily with soap and water and to powder them liberally with talcum, a product that most women had never seen and in any event weren’t in a position to buy. During much of the doctor’s lecture, women chatted and giggled among themselves. His presentation to a mixed group of men and women, offered the next day, garnered greater attention. He urged women to stop swallowing the head lice that they harvested while grooming one another because, he said, lice harbor microbes that cause stomach disorders. A hullabaloo immediately arose among the men, who mocked their wives and ordered them to stop eating lice, an activity in which several were at the time avidly engaged. The men’s sense of superiority was dented moments later when the doctor criticized their habit of frequent spitting. “A most unsanitary practice,” he said. He was unaware that spitting was less a nervous tic than an obligatory, ritualized element of men’s formal speech.1

A memorable moment in the last of the public events was a talk by Winston Vásquez, a representative of the Ministry of Education. Vásquez expressed disapproval of the way the Awajún arranged their houses. Gesturing toward the surrounding village, he said, “Just look at this community! It’s ugly. You need to construct a central plaza, locate government buildings next to it, and then situate houses around it in straight rows. That’s what a well-organized place looks like.”

The specific phrase that Vásquez used for the urgently needed village square was plaza de armas. In Hispanic America, this marks the local apex of civil authority as well as the store of weapons that were used to defend it in colonial times. The apparently innocuous recommendation that the Awajún reorganize themselves around a plaza de armas was a condensed nugget of the central political values of civilization: social hierarchy, centralized governance, and physical separation of rulers from the ruled.

More profoundly still, Vásquez’s notion of order was blind to the logic of the Awajún’s accommodation to life in the rainforest. In Shimpiyacu and Huascayacu, house sites were chosen for their privacy, good drainage, proximity to water, and other practical considerations. The scruffy mix of packed soil and erratically distributed plants that surrounded most houses was, upon close inspection, a living cache of essential raw materials. There were chili peppers and edible fruits to enliven meals; herbal medicines, including ginger, nettle, and dozens of others, to treat everyday skin infections or muscle pain; trees such as achiote and huito that provided dyes; gourd squashes that served as drinking bowls and beer strainers; and psychoactive plants such as tobacco and angel’s trumpet (Brugmansia sp.), used in healing. What seemed like a contest between order and disorder, developed and underdeveloped, was in fact a struggle between civilization’s need to encode power relations in built space and an Amazonian logic of pragmatism and household self-sufficiency.

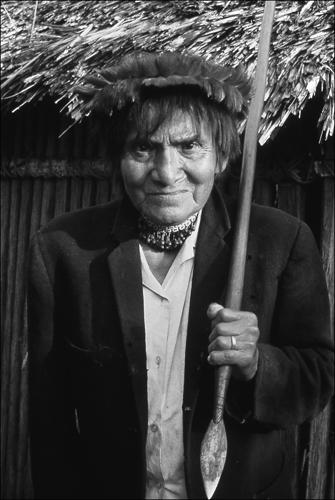

It was during house-to-house socializing in Shimpiyacu that I first met Míkig, one of the oldest men in the Alto Mayo. I guessed that he was in his seventies, but there was no reliable way to fix his age. Like other old-timers, Míkig spoke with a deliberate formality that gave him substantial presence, far more than his thin, leathery form could account for. Wrinkles creased his face like lines on a topographic map of the Peruvian montaña. Circles and crosshatches tattooed long ago into his chin, cheeks, and nose had faded to blue-black shadows. His gravelly voice wasn’t easy to understand at first. Beneath the formality was a dry wit that had survived the ravages of time. This, along with a penchant for colorful turns of phrase, made him a compelling storyteller. In the coming months I returned to Shimpiyacu several times in the hope that Míkig would pull more stories out of the vast library of his memory. I was rarely disappointed.

Míkig’s accounts of his early encounters with non-Awajún people were simultaneously strange and hilarious. He lavished special attention on enigmatic gringos whom he depicted as bosses of the local mestizos. “These gringos were tall and substantial-looking,” Míkig said. “They wore special coats, and as they walked the coats sounded like this: sáku, sáku, sáku. They were great talkers, and they loved to joke around.” The identity of these jovial gringos was a mystery, as was the sound of their coats. Perhaps they were military officers or European-looking government officials from Lima.

Míkig told more serious stories, too. When asked how long the Awajún people had been dealing with sorcerers, he answered, “A very long time. The first witch was named Púnku. Back then, it was easy to become a vision-bearer, a wáimaku. One could touch the ant called tíiship and become wáimaku.” Vision-bearers, Míkig implied, were nearly impossible to kill. They were protected by their spiritual strength. So Púnku, the first sorcerer, set out to undo this. “Púnku bewitched the ant tíiship so that men couldn’t use it to obtain a vision. This witch also created malaria and influenza. One day Púnku played with his niece and bewitched her arm and nose, the places where he had touched her. He was evil. They were collecting a fruit called inák. He told his niece to come down from the tree. He tried to have sex with her, and she said, ‘Uncle, why are you doing that?’ She returned to her house and became ill with fever. Before dying, she told her family of the attempted rape. Púnku had bewitched her, she insisted. The people came to kill Púnku for being a witch. It rained, and then the sun came out. Púnku began to cry, pretending to repent. ‘How bad witches are!’ he said. ‘Why did I do this to my niece?’ The people attacked him, speared him to death. When he died, witchcraft declined a little. But it never went away, because he had created it.”

Formal portrait of Míkig Daicháp, Shimpiyacu, 1977.

Photograph courtesy of Michael F. Brown.

Míkig’s story touched on a key element of traditional life whose current status was uncertain. In common with other Jivaroan peoples, the Awajún believed that the well-being of men, and to a lesser extent of women, depended on the acquisition of powerful visions. In the past, adolescent boys undertook a vision quest that might last weeks or months. They fasted from desirable foods, eating only a few roasted plantains each day. They slept in special high beds that shielded them from contamination associated with sexual activity, human wastes, and domestic animals. Above all, they consumed mind-altering plant substances: tobacco; juice squeezed from the angel’s trumpet, a close relative of jimsonweed; and the bitter, stomach-churning brew ayahuasca, made from the Amazon’s famed visionary vine. Sitting alone in a forest shelter adjacent to places that harbored ancient warrior spirits called ajútap, they sang and fasted and stood their ground against terrifying apparitions unleashed by the hallucinogens. With courage and a bit of luck, they were eventually visited by an ajútap who pronounced them to be ruthless, invincible warriors destined to ravage distant enemies and sorcerers closer to home. People insisted that a man in possession of this kind of vision was transformed almost beyond recognition. His thinking and speech became clear, and he acted with unshakable confidence in his invincibility.2

Women, it was said, sometimes sought similar visions. But instead of receiving the power to kill, they saw a future marked by healthy children, gardens dense with manioc stems, and frothy pots of manioc beer.

All the middle-aged men of Huascayacu had sought visions in their youth. But the introduction of primary schools and the arrival of Awajún teachers sympathetic to Christianity put a stop to this. Men expressed few regrets, although elders often grumbled about the misbehavior of youths regarded as sex-crazed because they had never submitted to the privation and self-discipline of the vision quest. In essence, the complaint was that today’s young men were psychologically unbalanced because they hadn’t taken powerful drugs that would show them how the world really worked behind the façade of everyday appearances.

Míkig shared a story that in compressed form revealed the values embedded in the search for visionary power. “Long ago young men couldn’t have intercourse with women because when the woman’s ‘dirt’ entered a man’s body he would become pregnant. This dirt, called shúpa, is like a child. A youth named Dáwa became pregnant this way. There was a party at his house, but Dáwa could only warm himself by the fire like a pregnant woman. He lay on his wooden shield. To tease him, the partiers sang, ‘How can they say that Dáwa is a man? Uh au uh au.’ People flipped the shield over to torment him. All he could say was, ‘Please leave me alone!’

“His brother said, ‘What made you like this? What happened to your courage? I’ve watched you like this for a long time. Why is your stomach bloated?’ His brother picked him up, handed him a small net bag, and said, ‘Go to the forest shelter.’

“Dáwa came to the shelter. In another shelter nearby some ajútap spirits were talking. One said to the others, ‘Let’s see whether he comes of his own free will.’ One ajútap, a jaguar, sent the bird súgka to look. The súgka said, ‘He comes not because of his own desire but because he is pregnant with shúpa.’ The jaguar sent the mouse katíp to confirm this. The mouse said, ‘He comes because he has shúpa.’ The jaguar emerged from the shelter with a terrifying sound. Hearing the roar, Dáwa tried to escape. The jaguar ajútap knocked him down. With its paws it squeezed out the shúpa baby in his belly. The baby began to cry, and the jaguar ate it.

“Dáwa received a vision. A great storm arrived, with much wind. His brother, still drinking beer at the party, began to weep because he thought that a falling tree would surely kill Dáwa.

“Dáwa returned to the stream near his house, washed and combed his hair, and entered the house carrying his lance. His stomach had returned to normal size. He spoke of his vision. They killed a hen for a feast and served him manioc beer. They celebrated his good fortune. ‘This is why I sent you to the shelter,’ said Dáwa’s brother.

“They formed a war party. They killed many enemies and took their heads. Dáwa arrived with a tsántsa, a smoked trophy head. He sent a messenger ahead to say that he wanted to perform the special tsántsa dance with the girl who had laughed at him most when he was pregnant. The messenger informed the girl, and she was frightened. ‘What will I say?’ she asked. She could only speak nonsense like ‘Opening his mouth, the man laughs.’ She threw herself under a sleeping platform, began to shit polliwogs, and died. She died of shame. Her name was Yancháp.”

The story emphasizes the corrupting, emasculating effect that contact with women was said to have on young men, who were pressured to achieve spiritual maturity before they engaged in sexual adventures. It is no accident that the tale shifts immediately from Dáwa’s vision to his participation in a killing expedition. Possession of a vision meant not just protection from enemies: vision-bearers were fated to defeat their adversaries and harvest heads for rituals that brought life-giving energies to their families. A man named Héctor once told me, apparently without ambivalence, that his late father’s status as a visionary warrior made it easy for him to kill others. “He was small and looked like a boy, but he was a wáimaku. He killed for pleasure, like a hunting dog.”

For men of Míkig’s generation, warfare and head-taking directed against distant enemies—notably, the Wampis people—had already faded into the past. Their adversaries were family members, sometimes close ones. One of Míkig’s neighbors, Santiago, spoke of this in response to a question about past conflicts: “We fought to execute sorcerers who killed even their own family members—their fathers, brothers—by witchcraft. My brother-in-law went to visit in the Río Potro, and there his brother gave him sorcery darts. He came back here having become a sorcerer. A woman died, and he was blamed. My relatives waited for him on the trail. He had gone to fish with poison and returned with his wife. He carried his gun. They began to shoot at him. He ran away, unhurt, but his wife called him back to fight. She said he was a wáimaku, a vision-bearer, and could not be killed easily. He came back and fired his gun, in vain. They killed him. His family wanted vengeance, but they couldn’t get it.”

Santiago said he had murdered his father’s brother after his father died from sorcery. “I killed the sorcerer with the help of others. It didn’t matter that he was in our family. He was a sorcerer. He lived in the same place, very close by. His relatives demanded payment, and I paid. But they continued the feud and attacked another uncle of mine. He left the house to defecate. They attacked him as he came in the door. He came in covered with blood, but he was just wounded. He had won. There were four of them, just boys. They didn’t defeat us. Again we made an agreement not to fight. They wanted to continue the feud, though.… Then the teacher Humberto arrived and the fighting ended.”

These histories of murderous visions and fratricidal violence, about which Míkig, Santiago, and other mature men spoke so matter-of-factly, were steadily losing relevance. Warrior values were still in place, but the realities of the colonization frontier were shifting power toward those with new skills: literacy, bilingualism, nimbleness in adapting indigenous cultural understandings to those of Peruvian national society. Evangelical Christianity represented another new avenue of power as well as a challenge to tradition. Young men and a few talented young women were gaining purchase on these assets. Pushed aside were the monolingual middle-aged men who should have been reaching the peak of their influence. They and their incendiary visions of martial virtue were fast becoming obsolete.