“How should we explain to someone what an epistolary novel is? I imagine that we should describe epistolary novels to him, and we might add: ‘This and similar things are called epistolary novels.’ And do we know any more about it ourselves? Is it only other people whom we cannot tell exactly what an epistolary novel is?—But this is not ignorance. We do not know the boundaries because none have been drawn. To repeat, we can draw a boundary for a special purpose. Does it take that to make the concept usable? Not at all! (Except for that special purpose.).”

With these words, Ludwig Wittgenstein explains the ambiguity of the concept of “game” (Philosophical Investigations 69)—slightly altered here to suit the purpose. The unstructured variety of games makes it impossible to name a common trait of, for example Soccer, “Duck, Duck, Goose,” skipping rope, or “World of Warcraft,” although all are called “games.” What Wittgenstein describes as the problem with any concept in human language is naturally also significant for the literary concept of genre. The intricacy of the genre of the epistolary novel in general is that it is almost impossible to define generic boundaries. This is, among other things, due to a “dangerous liaison”: the blending of two genres which in themselves have no fixed shape; neither the novel nor the letter can be described in a proper way without excluding texts which (should) belong to these two genres (for the ambiguity of the letter form, see Trapp 2003, 1–5; on the genre of “novel,” see Goldhill 2008). In the history of research on ancient epistolary novels, the uncertainty about the generic delineation is the leading question.

In 1697, Richard Bentley exposed the fraudulent character of some collections of letters of ancient prominent writers, as the tyrant Phalaris, Themistocles, Socrates, and Euripides. Though Bentley focused on this quest for authenticity, he nevertheless paved the way for subsequent classicists to read ancient epistolographic literature without regard of their presumed rhetorical character: it now became possible to analyze the texts without considering the relationship between addressee, addressor, and the epistolographic situation. Henceforward, however, classical philologists have still scrutinized ancient collections of letters under the leading question of their authenticity, ignoring the narratio of the (collections of) letters.

Only in the beginning of the twentieth century did an awareness of their literary character arise, though the ancient texts were read from their presumed modern counterpart. Richardson, the “father of the epistolary novel,” set the yardstick for the genre with his novels Pamela and Clarissa: “The archetype of this genre for one brought up in the English cultural tradition is obviously Richardson’s Pamela; and we expect certain criteria to be fulfilled if any other work of literature is to be classified as a member of the species” (Penwill 1978, 84).

The first to pay close attention to the genre was Sykutris in 1931. In Realenzyklopädie, he wrote two columns on the “ancient epistolary novel” in his article on “epistolography.” He compares ancient (Chion, Hippocrates, and Themistocles) with modern epistolary novels and concludes that the ancients do not show such “characteristic” elements as preface, marginal notes, and epilogue of the editor. Furthermore, he notes that the ancients are exclusively historic in orientation (based on ethopoiia), whereas the modern novels are set in the contemporary society and deal with the inner life and emotions of the protagonist. Thus, the genre aims at entertainment, not education.

Nevertheless, it took another 20 years before, in the course of critical editions, attention was drawn again on the literary character. Merkelbach popularized the genre with his attempt to reconstruct the source of the Alexander Romance from fragments of letters preserved on papyrus (Merkelbach 1947; 1954/1977, 11–19, 48–55, 70–72; Rosenmeyer 2001, 169–192, 251–252). By comparing the text of the letters with other letters from pseudo-Callisthenes, he argued that an epistolary novel was the nucleus of the later romance. He abstained from giving specific generic characteristics, though, and referred to the letters of Chion, Themistocles, the Seven Sages, and Alciphron. A coherent story and the connection of the letters by means of common motives and further links would be sufficient to attribute a collection of letters to the genre.

In his edition of the letters of Chion, Ingemar Düring (1951, 7, cf. 18; 23) narrowed the genre by claiming: “In epistolary literature the letters of Chion of Heraclea hold a unique position as the only extant example of a novel in letters.” The opposite position was taken by Norman Doenges in his edition of the letters of Themistocles (1954, published 1981). He proposed that any transmitted collection of letters should be analyzed with a narratological focus, instead of restricting the analysis to the question of authenticity or on the search for generic boundaries (Doenges 1981, 48; cf. Sykutris 1931, 213). Doing so, the question arises why the letters were passed down as a collection and whether different sequences of the letters in different collections reveal specific intentions. Though both come to opposing conclusions about the genre, they concur in respect to the characteristics of the novel: the collections have got to be a “unified work” (Doenges 1981, 8), a “coherent whole” (Düring 1951, 7); “not a random collection” (Doenges 1981, 11), they must be “composed like a drama” with exposition, retardation, peripeteia, and a moving exodus (Düring 1951, 7). Whereas for Düring this dramatic composition is realized by a chronological order (ordo naturalis) of the letters, Doenges sees the dramatic order (ordo artificialis) to be independent of the chronology. With respect to the intention of the genre (next to their entertaining character), Düring (1951, 7) highlights the moral philosophical tendency; Doenges (1981, 40) on the other hand favors an educational intention.

It was Düring’s evaluation of the letters of Chion as the only extant example of the genre that formed the communis opinio, though this attribution was not based on a critical analysis of a sample of possible texts. Instead, the concept of the epistolary novel was derived mainly from modern examples of this genre, especially from Richardson’s novels, which are characterized by systematic plot development, coherent and cohesive structure, an identifiable series of developing themes, and consistent characterization (Penwill 1978, 84; Rosenmeyer 2001, 233).

In 1994, Niklas Holzberg took a different approach. He was the first to scrutinize multiple epistolary collections and thus established a set of generic criteria for the ancient epistolary novel. These texts were the letters of Plato, Euripides, Aeschines, Hippocrates, Chion, Themistocles, and finally the letters of Socrates and the Socratics. Through this synoptic reading, he discerned some common traits of the collections: they give insight in the life of a famous person from the fifth–fourth centuries BCE, and the principal motive is the reflection on the relationship between an intellectual and the political sphere (set in the polis), mostly his dealings with a tyrant. Since the main part of the texts were written or composed in their final form between the late second century BCE and the third century CE and deal with the question of personal integrity in facing an autocrat, Holzberg claimed the time between the decline of the Roman republic and the establishment of a Christian empire to be the golden age of the ancient Greek epistolary novel (and thus he excludes texts from the genre which do not fit his catalogue of criteria, as inter alia, Epp. Alex., Epp. Hippocr. 18–24; see also Rosenmeyer 2001, 220).

“How should we explain to someone what an ancient epistolary novel is?” There are three opposing answers to this question. The first one reads the ancient texts with the poetics of the modern epistolary novels in mind, especially Richardson’s. Here, the genre is confined to a very limited number of books of pseudo-epigraphical letters, mostly Chion (e.g. Düring 1951; Rosenmeyer 1994, 2001). The next approach reads a sample of collections of letters (which exhibit some similarities) and extracts a set of generic criteria for a typology of the ancient epistolary novel. Here, the scope of texts is wider than before; it is, however, arguable whether the pre-selection of some “ideal” historical novels in letters does credit to the genre and justifies the exclusion of other epistolary texts (Holzberg 1994; Luchner 2009). The third answer to the question makes use of the concept of genre as a hermeneutical device to interpret the texts by focusing on the construction of the narrative world (Sykutris 1931; Doenges 1981; Glaser 2009a). With a generic approach based on Wittgenstein’s concept of family resemblances, the question of the defining characteristics of the genre must remain unanswered. The best one can do is to follow Wittgenstein’s advice and describe some of the novels—bearing in mind that one might add to each example: “This and similar things are called ‘epistolary novels’.”

To classify epistolary fiction as a novel in letters within the third approach, it needs a collection of letters which are linked in such a way that the reader can discern a plot running through the letters which points to a story “behind” the letters. From this “definition,” three secondary consequences can be derived.

First, epistolary fiction is a kind of autodiegesis, a first-person narration. This implies that the starting point for the interpretation of epistolographic literature is the narrative world, not the real world. Any reference to historical incidents, persons, etc., cannot be taken as historiography or biography (see Rosenmeyer 1994, 147: “epistolary technique always problematizes the boundary between reality and fiction”). Second, in close connection with the first consequence, the letter is more a mask rather than a “mirror of the soul” (Demetrius de elocut. 227) (see also Rosenmeyer 2001, 5: “Whenever one writes a letter, one automatically constructs a self, an occasion, a version of the truth. Based on a process of selection and self-censorship, the letter is a construction, not a reflection, of reality”; cf. Trapp 2003, 3–4). The author of the letter book depicts the letter writer in a way which is not per se in accordance with the tradition on the presumed author (e.g. Euripides), nor does this picture of the hero have to aim for a specific impact on the outside world (e.g. an apology for the poet). Instead, the function of the references and the self-dramatization for the narrative world must be elaborated. Finally, a distinction must be made between the implicit (i.e. real) and the explicit reader (i.e. the addressee). Epistolary novels create the fiction of a real communication between the writer of the letter and its recipient. In reality, an epistolary exchange substitutes or complements direct communication (cf. Demetrius de elocut. 223), and thus the partners have a common history which the fictitious letter writer and the real reader do not share. Where the explicit reader has sufficient background knowledge to understand the allusions of the writer, the implicit reader has to decipher these. Partly, he or she can do this by combining hints spread over the entire book of letters (see Rosenmeyer 1994, 161: “For an epistolary novelist, the initial withholding of information from the external reader is a generic necessity.”); partly, he or she can fill in the gaps between the clues with knowledge from his or her “encyclopedia” (in U. Eco’s sense); and partly, it is not possible to decrypt every single allusion. This is not due to the fragmentary character of the tradition (though it can be), but is also a narrative device in epistolary fiction (on the oscillation between the explicit and implicit reader in epistolary fiction, see Glaser 2009b).

Next to these “hermeneutical” consequences for the interpretation of epistolary fiction, there are some narratological structures that can be observed frequently in epistolary novels. The first sentence(s) of the first letter often summarizes the leitmotif of the novel (Eurip. 1.1; Themist. 1.1; Aisch. 1.1; Seneca 1.1.1; Titus 1.1–4). The last letter often is a farewell letter set at the eve of the writer’s death (Chion 17; Aesch. 12; Themist. 21; 2 Timothy). Especially in extensive novels, the letters are structured in blocks dealing with single topics (see Holzberg 1994, 47–52). Some of these traits can be illustrated on the subsequent pages. An English overview of ancient epistolary novels is given by Holzberg (1996), while an extensive bibliography is compiled by Beschorner (1994).

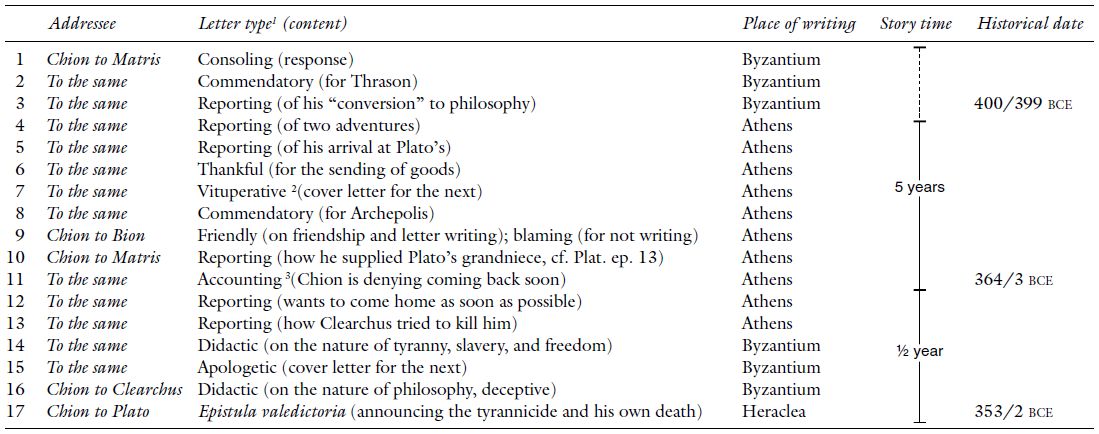

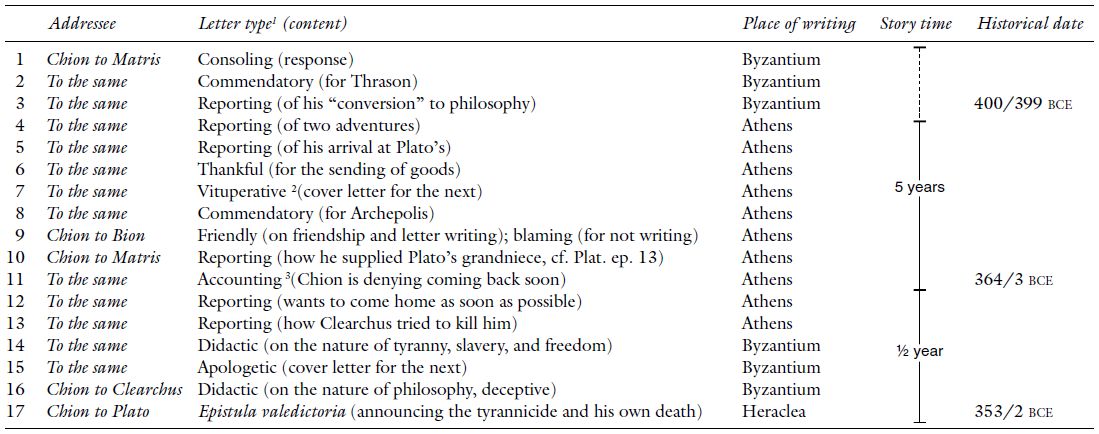

A generally accepted epistolary novel is the one about Chion, a young aristocrat from Heraclea on the southern coast of the Black Sea. The novel is made up of 17 letters, most of which are addressed to his father Matris, who was once a student of Socrates and wants his son also to study philosophy in Athens. Though young Chion is very reluctant to do so (he thinks philosophers to be idle folk and useless for their hometown), he nevertheless follows his father’s wishes and starts his maritime voyage to Athens. On the way, the ship stops for a few days in Byzantium where the young man experiences his “conversion,” as he informs his father in Ep. 3. Greek soldiers have just come back from their Persian campaign known as the “Anabasis” and are on the verge of plundering the city. Their captain Xenophon, a former student of Socrates, is hindering them by an impressive speech. Seeing this and after a short conversation with Xenophon, Chion starts to believe in the usefulness of philosophy and is eager to learn philosophy in Athens and become a courageous and valuable member for his polis. In the course of the letters, he informs his father about things happening to him of a mundane character; the uninformed reader who hoped to find easy knowledge of Platonic philosophy in this novel is disappointed. Instead, the reader learns how Chion acquires virtues of every kind within 5 years.

The novel takes a turn as soon as Chion is informed by his father that his fellow citizen Clearchus has established tyranny in Heraclea. Though the tyrant tries to kill his philosophical opponent by an agent (Ep. 13), Chion successfully convinces him of the idleness of philosophy (Ep. 16): The only thing philosophers want to do is sit or walk around and have the muse and quietness (hesychia) to be able to think. Political participation is of no interest at all for a true philosopher. This letter addressed to Clearchus is sent as a copy to his father with an accompanying letter that decodes the deceptive letter. In this, he assures Matris that he would come back as soon as weather allows, to free the polis from tyranny.

The last letter, a letter of farewell to his teacher Plato, informs the reader of the next step: In 2 days, a procession will take place in which Chion will find an opportunity to kill Clearchus. He is in no doubt that he will die himself in the attack. Yet, he has learned his lesson from Plato—that for a philosopher the welfare of the city and his kin is way more important than one’s own. With this prospect, the novel comes to its end.

As is obvious in this short summary of the plot, the novel shows a close resemblance to modern coming-of-age novels with its focus on the inner self of the young hero (Rosenmeyer 2001, 250, calls the novel “an epistolary ‘Bildungsroman’”). For this very reason, it is estimated “as the only extant example of a novel in letters” (Düring 1951). Yet, this novel can highlight a specific aspect of ancient epistolary fiction: one may ask, to what end is an epistolary novel written? It has long been argued that it is engaging the political discussion on how to face tyranny (politeuesthai is a central term of the novel; see Konstan and Mitsis 1990, 272; Düring 1951, 8–25). Indeed, it can often be observed, as Holzberg has elaborated, that the question of political participation is vital in a good deal of those novels. However, to what extent is this novel taking part in the discussion? Because it shows a young nobleman becoming vigorously opposed to a tyrant and ends with the plan to throw down tyranny, it was suspected that this novel was written by someone involved in the philosophical opposition against Domitian and was meant to be a kind of exhortation literature in the guise of art. This may be so, though there are clues in the novel that imply this reading strategy does not exclude others. These clues, to be sure, could only be discerned by the more sophisticated reader. The novel illustrates how the meaning of a text can change with differing background knowledge. If one only relates to the story communicated in the novel, the aforementioned way of reading the moral becomes intelligible. However, for the well-informed reader, the novel relates the opposite message.

The novel ends at the eve of tyrannicide. But the stories of what happened after is revealed by some authors, who are roughly contemporaries to the author of the letters, first–second century CE. Clearchus was dead and Chion was killed, as he suspected in his farewell address. What is more, Clearchus’ brother Satyrus followed him up in tyranny and became an even crueler autocrat. Chion’s whole family was extinguished, as were the families of his fellow-assassins (Phot. cod. 224, 222b–223a). Considering this end, the moral could also be: “Philosophers may make up ideal worlds and political ideas—but these are just a kind of cloud cuckoo-land; politics in the real world follow a different pattern and logic.” (This reading of the novel’s strategy was considered by Konstan and Mitsis 1990, 277, and Rosenmeyer 2001, 249; 1996, 162–163.)

This observation raises the question of how much background knowledge an author of an epistolary novel presupposes. And it stresses the importance of taking into account different ways of reading and evaluating literature. In the novel on Chion, it is interesting to observe where the story ends and what is not being narrated, whereas the novel about the poet Euripides seems to tell two stories at the same time: the story as well as the counter-story.

Ancient as well as modern biographies and historical sketches maintain that the poet Euripides went to Pella, the newly founded capital of Macedonia, to King Archelaos, in approximately 407 and died there a year and a half later (see Gavrilov 1996; Scullion 2003 for historicity of Euripides in Pella). The short epistolary novel (five letters) takes its starting point from this scenario. The author, writing at the beginning of the second century CE, explains how it came about that the poet went to Pella. The novel begins with Euripides in Athens giving his negative response to the king’s invitation. As is observed quite often with epistolary novels, the first sentences introduce the main points of the whole book. Here, these would be the generosity of Archelaos as patron of an artist, the independence of the poet, his influence on the monarch, and his philanthropia. In the course of the letters, the reader can follow how the poet uses his influence on the monarch to ameliorate his way of ruling. The last letter, then, is written from Pella to a friend in Athens who has reported to Euripides some malevolent rumors concerning his decision to court a king for the purpose of power and money.

The letters of Euripides are especially interesting to illustrate how epistolary novels can create their story with reference to prior stories. The biographical tradition about the poet refers mainly to his plays as well as those of Aristophanes. Through this medium, they conjure up a mysterious, romantic picture of a reclusive hermit who lives in his cave at the shore, avoids people, hates and is hated by women, and in these circumstances and conditions writes his ingenious plays (Jouan and Auger 1983). The novel, on the other hand, depicts him as someone who lives amidst people, shows a sense of societal responsibility, and hardly ever becomes visible as a playwright.4 This different display of Euripides is explicitly stated in the letters by the relationship to his colleague and rival Sophocles as he writes in the final letter (Ep. 5.5): “Concerning Sophocles, I was not always the same as it might be known,” before proceeding to report how the two became inseparable friends, once he realized that Sophocles was not that eager for honor as he first believed him to be.

At this point, the biographical tradition could rely on the letters, or vice versa. Euripides says (Ep. 5.6): “I never hated him [Sophocles], to be sure, and I always admired him, but I did not always love him as I do now. I thought he was a man rather given to ambition (philotimoteron) and so I looked askance at him, but when he proposed to make up our hostility I eagerly accepted him” (trans. Kovacs 138–139). A quite similar point is made in the genos (34), yet with a different focus, bringing to light the antithetical character of both poets: “It was for this reason that he was rather proud and pardonably stood aloof from the majority, showing no ambition (philotimia) as regards his audience. Accordingly this fact hurt him as much as it helped Sophocles” (trans. Kovacs 8–9). The “charge” of striving for philotimia or the reluctance to do so, respectively, is formulated from two different perceptions. Now, letter two becomes intelligible, which is otherwise unconnected to the Archelaos story: Euripides is being portrayed as a close friend of Sophocles who worries about him and looks after his affairs while he is out of town.5

While the biographical tradition has stylized the two poets as antithetical (already rooted in Aristophanes’s account in Frogs 76–82, 787–793), the novel exhibits them in perfect harmony: on Sophocles, the vita lines 31–32 states that “he was loved by everyone and everywhere” (Καὶ ἁπλω̑ς εἰπει̑ν τοσαύτη του̑ ἤθους αὐτ γέγονε χάρις ὥστε πάντῃ καὶ πρὸς ἁπάντων αὐτὸν στέργεσθαι). As an opposition to Euripides, one can read the following statement (lines 37–38): “He [Sophocles] was filled with such a love for Athens that he wasn’t willing to leave his native city, though a lot of kings did call him” (Οὕτω δὲ φιλαθηναιότατος

γέγονε χάρις ὥστε πάντῃ καὶ πρὸς ἁπάντων αὐτὸν στέργεσθαι). As an opposition to Euripides, one can read the following statement (lines 37–38): “He [Sophocles] was filled with such a love for Athens that he wasn’t willing to leave his native city, though a lot of kings did call him” (Οὕτω δὲ φιλαθηναιότατος  ν ὥστε πολλω̑ν βασιλέων μεταπεμπομένων αὐτὸν οὐκ ἠθέλησε τὴν πατρίδα καταλιπει̑ν). Compare to this the statements in the dialogical Euripides biography of Satyrus (third century BCE), which is only preserved in fragments (P.Oxy. 9.1176), fr. 39.10: “Everyone became his enemy, the men because he was so unpleasant to talk to, the women because of his abuse of them in his poetry. He ran into great danger from both sexes” (translation by Kovac 21); fr. 39.15: “He, partly in annoyance at the ill-will of his fellow-citizens…” and in the following his renouncing Athens and going to Macedon is told (fr. 39.17–19).

ν ὥστε πολλω̑ν βασιλέων μεταπεμπομένων αὐτὸν οὐκ ἠθέλησε τὴν πατρίδα καταλιπει̑ν). Compare to this the statements in the dialogical Euripides biography of Satyrus (third century BCE), which is only preserved in fragments (P.Oxy. 9.1176), fr. 39.10: “Everyone became his enemy, the men because he was so unpleasant to talk to, the women because of his abuse of them in his poetry. He ran into great danger from both sexes” (translation by Kovac 21); fr. 39.15: “He, partly in annoyance at the ill-will of his fellow-citizens…” and in the following his renouncing Athens and going to Macedon is told (fr. 39.17–19).

Here, it can be observed how the letters contradict other stories.6 However, what is even more interesting in the way the letters construct their story is the following: a principal motive behind the letters is the apology of the poet against charges leveled at him for his being at a tyrant’s court. Throughout the novel, he argues for the benefit that a monarch can draw from the association with intellectuals. Yet, such a charge is virtually absent from the whole Euripides tradition.7 It is only by means of the apology that the charge is created; that is to say, by creating the story, the novel also creates the counter story. As soon as this “play with stories” is regarded as the principle aim of the author, it becomes comprehensible why there is no positive explanation for Euripides’ association with the king, though he is promising the recipient that “he will cease to be ignorant of the causes and at the same time to condemn me—as is natural for one in ignorance to do—as greedy for gain” (Ep. 5.2, translated by Kovacs 137).

The epistolary novels analyzed so far by classicists treat the “dangerous liaisons” between a hero of Greece’s classical past and political power (Euripides/Socrates vs. Archelaos; Chion vs. Clearchus; Hippocrates vs. Artaxerxes; Plato vs. Dionysios; Aeschines vs. the Athenian polis; etc.), and are set to the final stage of the hero’s life. Christian communities adopted this genre in the second century to tell similar stories of their “heroes.” Since the letter was the commonly used device for communication between the communities scattered about the Empire, the epistolary novel was an appropriate genre to deal with comparable questions.

In the early second century, an author used this genre to answer the question how the Apostle Paul stayed in contact with his communities once he left, how he organized them, how he fought against heretics and opponents, and how he turned into a martyr. In the small collection of Pastoral Epistles, which are preserved in the canon of the New Testament, this moving story can be followed. By reading them from Titus via 1 Timothy up to 2 Timothy, the reader can see how Paul is changing gradually and what happened to him after his imprisonment. Where Acts end with the depiction of Paulus victor (cf. Acts 28:30–31: kerusson…meta pases parresias akolutos) and leaves the end of the Apostle open, 2 Timothy depicts Paul left alone and surrounded by his true fellows at the eve of his death in a Roman prison (4:6–22; see Pervo 1994; Glaser 2009a).

Later in the second century, another author has used an unknown martyr named Ignatius for providing an epistolary novel on the topic of Christian identity in the Roman Empire (although the majority of scholars estimate these letters as authentic, Hübner 1997 and others have demonstrated their fictional character). The plot of the novel runs as follows: Ignatius, Bishop of Antioch in Syria, having received death sentence there, is on his way to Rome, where he will be thrown to the beasts. On this journey through Asia Minor, he finds opportunity to receive delegates from the surrounding churches and involves heretics in theological discussions. The preserved seven letters he wrote from Smyrna and Troas to the communities in Ephesus, Magnesia, Tralles, Rome, Philadelphia, Smyrna, and to Polycarp, Bishop of Smyrna. In these letters, he exhorts the communities to follow their bishop, to fight against heretics, and he reflects on his impending martyrdom. The entire collection reveals an elaborate construction with many of the literary techniques which can frequently be observed in epistolary novels. Different from non-Jewish/Christian fiction, this novel takes up motifs such as travel, religion, and cultural identity (see Zeitlin, Stephens, and Romm in Whitmarsh 2008), and the genre in general to tackle current theological discussions. By reading the Ignatian letters as an epistolary novel, it becomes obvious why the author chose such a novel to promote this specific picture of a martyr bishop in dealing with the question of Christian identity. Dating the Ignatian letters to the time of Marcus Aurelius, they represent a voice in the debate on the relevance of the charismatic character of prophecy, of the martyr/confessor, and the resulting conflicts with ecclesiastical authorities. In the fourth century, the novelistic momentum of the Ignatian letters was enforced by augmenting and reediting them. In this so called “long recension,” the parallels between Ignatius and Paul are stressed by using the Pastoral Epistles extensively.

Also to the fourth century dates a book of (14) fictional letters that stages the epistolary communication between the Apostle Paul (imprisoned in Rome) and the Stoic philosopher L. Annaeus Seneca. Whereas in the “classical” epistolary novels the letter writer directly addresses a potentate, this scenario was implausible in early Christian epistolary fiction. The letter exchange between Paul and Seneca veers toward the pagan antecedents. Though Paul is not yet addressing his letters to Nero, his words and ideas are presented to the emperor by the intermediary Seneca, who informs the Apostle of the impression he made: confiteor, Augustum sensibus tuis motum…mirari eum posse ut qui non legitime imbutus sit taliter sentiat (Ep. 7). With this novel, the reader can observe how the Christian religion becomes more and more socially acceptable (see Pervo 2010, 110–116).

The intention of this tour d’horizon was to acquaint readers with the variety and flexibility of the ancient epistolary novel. By attributing Wittgenstein’s concept of family resemblances, books of letters can be understood as novels—“for a special purpose.” By reading epistolary books as novels, the reader becomes a detective, collecting the hints which build up the story “behind the letters,” and the focus of interpretation shifts to the construction of the narrative world and the masquerade of the letter writer. This does not imply that each collection of letters is a piece of fiction. For example, the letters of Synesios, fifth-century bishop of Cyrene, are an example of the use of the epistolary “I” for an artful self-portrayal (Hose 2003). These traits can also be observed in the letters from exile of the former bishop of Constantinople, John Chrysostom (Mayer 2006). Like Ovid’s letters, these letters display a highly stylized picture of an ostracized individual.

A final example for the adaptability of the genre can be found in Islamic literature. In the eighth century, a Christian Syrian secretary at the court of the Omayyad caliph translated a sixth-century Greek (presumably Christian) epistolary novel on Aristotle and Alexander into Arabic. This book of letters was intended as a Fürstenspiegel for the young monarch. Thus, the author provided, as it seems, with the reception of classical Greek literary tradition in the form of a “modern” genre, the first piece of Islamic prose fiction (Maróth 2006).

1 On the tupoi epistolikoi given by Ps.-Demetrius and Ps.-Libanius, see the edition by Malherbe 1988.

2 Ps.-Demetrius defines: “when we bring to light the badness of someone’s character or the offensiveness of (his) action against someone” (trans. Malherbe 1988, 37).

3 Ps.-Demetrius defines: “when we give the reasons why something has not taken place or will not take place” (trans. Malherbe 1988, 39).

4 The letters are, in addition, virtually unknown to the tradition on Euripides. The biographical tradition knows nothing of Euripides as a letter writer or hints to the content of the letters, and the letters are not handed down to us in conjunction with his plays; no edition of his works, which come mostly with biographical introductions, are supplemented with the letters. The first and only antique reference to our letters dates from the third century in the Aratus vita. See Gösswein 1975, 3 n. 1, 6–12, 24, 28; Jouan and Auger 1983, 186–187.

5 See Xen. Mem. 2.3.12 and Bentley’s reproach 1697, 127: “Must Euripides, his Rival, his Antagonist, tell him, That his Orders about family affairs were executed: as if He had been employ’d by him, as Steward of his Household?”

6 With regard to Sophocles, the letters make it explicit that tradition was changed. An uncommented change is made with regard to Cephisophon who, as the addressee of the last letter, appears as a close and loyal friend, while everywhere else he is named as the rival in love to Euripides’ wife; see Kovacs 1990.

7 Arist. Frogs 83–85 can be read as a similar charge against Agathon for his going “to the feast of the blessed” (Ἐς μακάρων εὐωχίαν 85; Kovacs 1994, 90–91), which is interpreted in some of the scholia as referring to the golden tables of Archelaos (see Chantry 2001). Possibly, Satyrus fr. 39.17 hints at such a charge against Euripides. There, an interlocutor (A) reports the protest Euripides brought forth against Athens in the form of a choral ode which states: “There are golden wings about my back and the winged sandals of the Sirens are fitted on my feet, and I shall go aloft far into the heavens, there with Zeus…” At this point, the fragment breaks off, while the next one (fr. 39.18) goes on “… began the songs. Or do you not know that it is this that he says? (Diodora:) What do you mean? (A:) In saying “mingle my flight with Zeus,” he hints metaphorically at the monarch and at the same time increases the man’s preeminence. (Di.:) It seems to me that you speak with more subtlety than truth. (A:) You may understand it as you like. At any rate, he went over and spent his old age in Macedonia, enjoying very high honor with the king…” (trans. Kovacs 25). The “golden wings” may hint at the charge of going there for money. However, as this is the only instance in the whole tradition, and due to the fragmentary character, one cannot be certain on this point. Diodora, however, does not give credence to the rumor. This could indicate that the author was not sure about it himself. As it seems, this was at least not widespread knowledge and could only have been known to the more sophisticated reader of the novel.

Bentley, R. 1697. A Dissertation upon the Epistles of Phalaris, Themistocles, Socrates, Euripides, and Others; and the Fables of Aesop. London: Buck.

Beschorner, A. 1994. “Griechische Briefbücher berühmter Männer. Eine Bibliographie.” In Der griechische Briefroman: Gattungstypologie und Textanalyse, edited by N. Holzberg. Classica Monacensia 8. Tübingen: Narr, pp. 169–190.

Chantry, M. 2001. Scholia in Aristophanem: Pars III. Ib Scholias recentiora in Aristophanis Ranas. Groningen: Forsten.

Doenges, N. 1981. The Letters of Themistokles. Monographs in Classical Studies, New York: Arno.

Düring, I. 1951. Chion of Heraclea. A Novel in Letters. Acta Universitatis Gotoburgensis 57.5. Göteborg: Wettergren & Kerber.

Gavrilov, A. 1996. “Euripides in Makedonien.” Hyperboreus, 2.2: 38–53.

Glaser, T. 2009a. Paulus als Briefroman erzählt. Studien zum antiken Briefroman und seiner christlichen Rezeption in den Pastoralbriefen. Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus 76. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Glaser, T. 2009b. “Erzählung im Fragment. Ein narratologischer Ansatz zur Auslegung pseudepigrapher Briefbücher.” In Pseudepigraphy and Author Fiction in Early Christian Letters, edited by J. Frey, et al. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 246. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, pp. 267–294.

Goldhill, S. 2008. “Genre.” In The Cambridge Companion to the Greek and Roman Novel, edited by T. Whitmarsh. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 185–200.

Gösswein, H.-U. 1975. Die Briefe des Euripides. Meisenheim am Glan: Anton Hain.

Holzberg, N. 1994. “Der griechische Briefroman. Versuch einer Gattungstypologie.” In Der griechische Briefroman. Gattungstypologie und Textanalyse, edited by N. Holzberg. Classica Monacensia 8. Tübingen: Narr, pp. 1–52.

Holzberg, N. 1996. “Novel-like works of extended prose fiction II.” In The Novel in the Ancient World, edited by G.L. Schmeling. Mnemosyne Supplements 159. Leiden: Brill, pp. 619–654.

Hose, M. 2003. “Synesios und seine Briefe. Versuch der Analyse eines literarischen Entwurfs.” Würzburger Jahrbücher für die Altertumswissenschaft, 27: 125–141.

Hübner, R.M. 1997. “Thesen zur Echtheit und Datierung der sieben Briefe des Ignatius von Antiochien.” Zeitschrift für Antikes Christentum, 1: 44–72.

Jouan, F. and D. Auger. 1983. “Sur le corpus des “Lettres d’Euripide.” Mélanges Edouard Delebecque. Aix-en-Provence. Publications Université de Provence. Marseille: Diffusion J. Laffitte, pp. 183–198.

Konstan, D. and P. Mitsis. 1990. “Chion of Heraclea: A philosophical novel in letters.” In The Poetics of Therapy: Hellenistic Ethics in its Rhetorical and Literary Context, edited by M. Nussbaum. Edmonton: Academic Printing & Pub, pp. 257–279.

Kovacs, D. 1990. “De Cephisophonte Verna, Ut Perhibent, Euripidis.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 84: 15–18.

Kovacs, D. 1994. Euripidea. Mnemosyne Supplements 132. Leiden: Brill.

Luchner, K. 2009. “Pseudepigraphie und antike Briefromane.” In Pseudepigraphy and Author Fiction in Early Christian Letters, edited by J. Frey et al. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 246. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, pp. 233–266.

Malherbe, A. 1988. Ancient Epistolary Theorists. Sources for Biblical Study 19. Atlanta: Scholars Press.

Maróth, M. 2006. The Correspondence between Aristotle and Alexander the Great: An Anonymous Greek Novel in Letters in Arabic Translation. Documenta et Monographiae 5. Piliscsaba: The Avicenna Institute of Middle Eastern Studies.

Mayer, W. 2006. “John Chrysostom: Deconstructing the construction of an exile.” In “Was von Anfang an war.” Neutestamentliche und kirchengeschichtliche Aufsätze, edited by T.K. Kuhn et al. Basel: Reinhardt, pp. 248–258.

Merkelbach, R. 1947. “Pseudo-Kallisthenes und ein Briefroman über Alexander.” Aegyptus, 27: 144–158.

Merkelbach, R. 1954, rev. ed. 1977. Die Quellen des griechischen Alexanderromans. Zetemata 9. München: Beck.

Penwill, J.L. 1978. “The letters of Themistocles: An epistolary novel?” Antichthon, 12: 83–103.

Pervo, R.I. 1994. “Romancing an oft-neglected stone: The Pastoral Epistles and the epistolary novel.” Journal of Higher Criticism, 1: 25–47.

Pervo, R.I. 2010. The Making of Paul: Constructions of the Apostle in Early Christianity. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

Rosenmeyer, P. 1994. “The epistolary novel.” In Greek Fiction: The Greek Novel in Context, edited by J.R. Morgan and R. Stoneman. London: Routledge, pp. 146–165.

Rosenmeyer, P. 2001. Ancient Epistolary Fictions: The Letter in Greek Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Provides a lively and accessible introduction for readers approaching the subject for the first time.

Scullion, S. 2003. “Euripides and Macedon, or the silence of the frogs.” Classical Quarterly, 53: 389–400.

Sykutris, J. 1931. “Epistolographie,” Realenzyclopädie, Supplement 5, 185–220.

Trapp, M. 2003. Greek and Latin Letters: An Anthology with Translation. Cambridge Greek and Latin Classics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Whitmarsh, T., ed. 2008. The Cambridge Companion to the Greek and Roman Novel, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Frey, J., M. Janssen, and C. Rothschild, eds. 2009. Pseudepigraphie und Verfasserfiktion in Frühchristlichen Briefen: Pseudepigraphy and Author Fiction in Early Christian Letters. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 246. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. Offers a wide range on up-to-date scholarship on the topic of Pseudepigraphy in Late Antiquity both in German and English.

Holzberg, N., ed. 1994. Der griechische Briefroman. Gattungstypologie und Textanalyse. Classica Monacensia 8. Tübingen: Narr. Offers the most thoroughly elaborated analysis of the genre of epistolary novel in Antiquity, some case studies, and an extensive bibliography.

Rosenmeyer, P.A. 2006. Ancient Greek Literary Letters: Selections in Translation. Routledge Classical Translations. London: Routledge. Can be used as a supplementary sourcebook for Rosenmeyer’s 2001 Introduction.