XLII

The Cross and the Crucifixion In Pagan and Christian Mysticism

O

ne of the most interesting legends concerning the cross is that preserved in Aurea Legenda,

by Jacobus de Vorgaine. The story is to the effect that Adam, feeling the end of his life was near, entreated his son Seth to make a pilgrimage to the Garden of Eden and secure from the angel on guard at the entrance the Oil of Mercy

which God had promised mankind. Seth did not know the way; but his father told him it was in an eastward direction, and the path would be easy to follow, for when Adam and Eve were banished from the Garden of the Lord, upon the path which their feet had trod the grass had never grown.

Seth, following the directions of his father, discovered the Garden of Eden without difficulty. The angel who guarded the gate permitted him to enter, and in the midst of the garden Seth beheld a great tree, the branches of which reached up to heaven. The tree was in the form of a cross, and stood on the brink of a precipice which led downward into the depths of hell. Among the roots of the tree he saw the body of his brother Cain, held prisoner by the entwining limbs. The angel refused to give Seth the Oil of Mercy,

but presented him instead with three seeds from the Tree of Life (some say the Tree of Knowledge). With these Seth returned to his father, who was so overjoyed that he did not desire to live longer. Three days later he died, and the three seeds were buried in his mouth, as the angel had instructed. The seeds became a sapling with three trunks in one, which absorbed into itself the blood of Adam, so that the life of Adam was in the tree. Noah dug up this tree by the roots and took it with him into the Ark. After the waters subsided, he buried the skull of Adam under Mount Calvary, and planted the tree on the summit of Mount Lebanon.

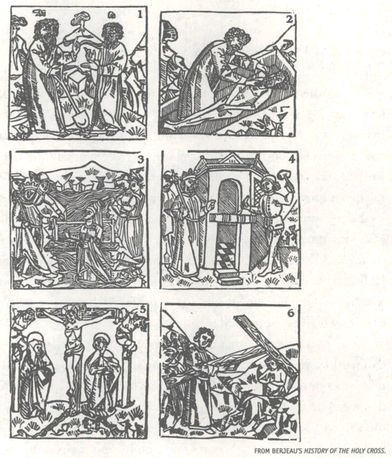

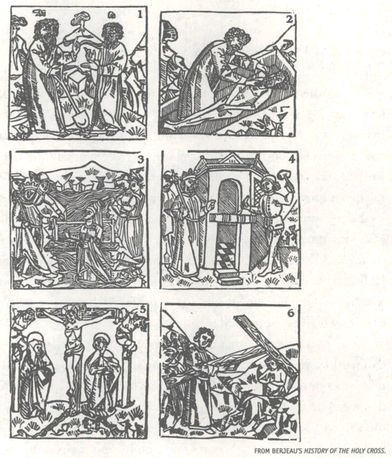

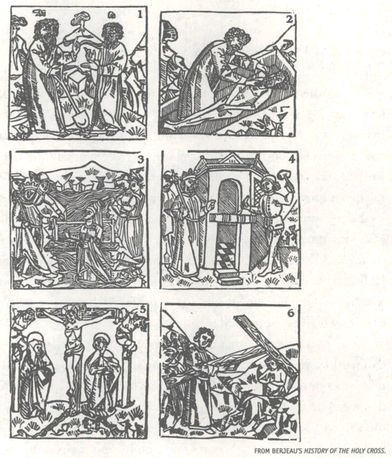

HISTORY OF THE HOLY CROSS.

(1) Adam directing Seth how to reach the Garden of Eden. (2) Seth placing the three seeds from the Tree of Life under the tongue of the dead Adam. (3) The Queen of Sheba, refusing to place her feet upon the sacred tree, forded the stream. (4) Placing the sacred tree over the door of Solomon’s Temple. (5) The crucifixion of Christ upon a cross made from the wood of the holy tree. (6) Distinguishing the true cross from the other two by testing its power to raise a corpse to life.

Moses beheld a visionary being in the midst of this tree (the burning bush) and from it cut the magical rod with which he was able to bring water out of a stone. But because he failed to call upon the Lord the second time he struck the rock he was not permitted to carry the sacred staff into the Promised Land; so he planted it in the hills of Moab. After much searching, King David discovered the tree; and his son, Solomon, tried to use it for a pillar in his Temple, but his carpenters could not cut it so that it would fit; it was always either too long or too short. At last, disgusted, they cast it aside and used it for a bridge to connect Jerusalem with the surrounding hills. When the Queen of Sheba came to visit King Solomon she was expected to walk across this bridge. Instead, when she beheld the tree, she refused to put her foot upon it, but, after kneeling and praying, removed her sandals and forded the stream. This so impressed King Solomon that he ordered the log to be overlaid with golden plates and placed above the door of his Temple. There it remained until his covetous grandson stole the gold, and buried the tree so that the crime would not be discovered.

From the ground where the tree was buried there immediately bubbled forth a spring of water, which became known as Bethesda.

To it the sick from all Syria came to be healed. The angel of the pool became the guardian of the tree, and it remained undisturbed for many years. Eventually the log floated to the surface and was used as a bridge again, this time between Calvary and Jerusalem; and over it Jesus passed to be crucified. There was no wood on Calvary; so the tree was cut into two parts to serve as the cross upon which the Son of Man was crucified. The cross was set up at the very spot where the skull of Adam had been buried. Later, when the cross was discovered by the Empress Helena, the wood was found to be of four different varieties contained in one tree (representing the elements), and thereafter the cross continued to heal all the sick who were permitted to touch it.

The prevalent idea that the reverence for the cross is limited to the Christian world is disproved by even the most superficial investigation of its place in religious symbolism. The early Christians used every means possible to conceal the pagan origin of their symbols, doctrines, and rituals. They either destroyed the sacred books of other peoples among whom they settled, or made them inaccessible to students of comparative philosophy, apparently believing that in this way they could stamp out all record of the pre-Christian origin of their doctrines. In some cases the writings of various ancient authors were tampered with, passages of a compromising nature being removed or foreign material interpolated. The supposedly spurious passage in Josephus concerning Jesus is an example adduced to illustrate this proclivity.

The Lost Libraries of Alexandria

Prior to the Christian Era seven hundred thousand of the most valuable books, written upon parchment, papyrus, vellum, and wax, and also tablets of stone, terra cotta, and wood, were gathered from all parts of the ancient world and housed in Alexandria, in buildings specially prepared for the purpose. This magnificent repository of knowledge was destroyed by a series of three fires. The parts that escaped the conflagration lighted by Caesar to destroy the fleet in the harbor were destroyed about A.D. 389 by the Christians in obedience to the edict of Theodosius, who had ordered the destruction of the Serapeum, a building sacred to Serapis in which the volumes were kept. This conflagration is supposed to have destroyed the library that Marcus Antonius had presented to Cleopatra to compensate in part for that burned in the fire of the year 51.

Concerning this, H. P. Blavatsky, in Isis Unveiled,

has written: “They [the Rabbis of Palestine and the wise men] say that not all the rolls and manuscripts, reported in history to have been burned by Caesar, by the Christian mob, in 389, and by the Arab General Amru, perished as it is commonly believed; and the story they tell is the following: At the time of the contest for the throne, in 51 B.C., between Cleopatra and her brother Dionysius Ptolemy, the Bruckion, which contained over seven hundred thousand rolls all bound in wood and fire-proof parchment, was undergoing repairs and a great portion of the original manuscripts, considered among the most precious, and which were not duplicated, were stored away in the home of one of the librarians. * * * Several hours passed between the burning of the fleet, set on fire by Caesar’s order, and the moment when the first buildings situated near the harbor caught fire in their turn; and * * * the librarians, aided by several hundred slaves attached to the museum, succeeded in saving the most precious of the rolls.” In all probability, the books which were saved lie buried either in Egypt or in India, and until they are discovered the modern world must remain in ignorance concerning many great philosophical and mystical truths. The ancient world more clearly understood these missing links

—the continuity of the pagan Mysteries in Christianity.

The Cross in Pagan Symbolism

In his article on the Cross and Crucifixion

in the Encyclopœdia Britannica,

Thomas Macall Fallow casts much light on the antiquity of this ideograph. “The use of the cross as a religious symbol in pre-Christian times, and among non-Christian peoples, may probably be regarded as almost universal, and in very many cases it was connected with some form of nature worship.”

Not only is the cross itself a familiar object in the art of all nations, but the veneration for it is an essential part of the religious life of the greater part of humanity. It is a common symbol among the American Indians—North, Central, and South. William W. Seymour states: “The Aztec goddess of rain bore a cross in her hand, and the Toltecs claimed that their deity, Quetzalcoatl, taught them the sign and ritual of the cross, hence his staff, or sceptre of power, resembled a crosier, and his mantle was covered with red crosses.” (The Cross in Tradition, History and Art. )

The cross is also highly revered by the Japanese and Chinese. To the Pythagoreans the most sacred of all numbers was the 10, the symbol of which is an X, or cross. In both the Japanese and Chinese languages the character of the number 10 is a cross. The Buddhist wheel of life is composed of two crosses superimposed, and its eight points are still preserved to Christendom in the peculiarly formed cross of the Knights Templars, which is essentially Buddhistic. India has preserved the cross, not only in its carvings and paintings, but also in its architectonics; a great number of its temples—like the churches and cathedrals of Christendom—are raised from cruciform foundations.

On the mandalas

of the Tibetans, heaven is laid out in the form of a cross, with a demon king at each of the four gates. A remarkable cross of great antiquity was discovered in the island caves of Elephanta in the harbor of Bombay. Crosses of various kinds were favorite motifs in the art of Chaldea, Phœnicia, Egypt, and Assyria. The initiates of the Eleusinian Mysteries of Greece were given a cross which they suspended about their necks on a chain, or cord, at the time of initiation. To the Rosicrucians, Alchemists, and Illuminati, the cross was the symbol of light, because each of the three letters LVX is derived from some part of the cross.

The Tau Cross

There are three distinct forms of the cross. The first is called the TAU (more correctly the TAV). It closely resembles the modern letter T, consisting of a horizontal bar resting on a vertical column, the two arms being of equal length. An oak tree cut off some feet above the ground and its upper part laid across the lower in this form was the symbol of the Druid god Hu.

It is suspected that this symbol originated among the Egyptians from the spread of the horns of a bull or ram (Taurus or Aries) and the vertical line of its face. This is sometimes designated as the hammer

cross, because if held by its vertical base it is not unlike a mallet or gavel. In one of the Qabbalistic Masonic legends, CHiram Abiff is given a hammer in the form of a TAU by his ancestor, Tubal-cain. The TAU cross is preserved to modern Masonry under the symbol of the T square. This appears to be the oldest form of the cross extant.

THE TAU CROSS.

The TAU Cross was the sign which the Lord told the people of Jerusalem to mark upon their foreheads, as related by the Prophet Ezekiel. It was also placed as a symbol of liberation upon those charged with crimes but acquitted.

The TAU cross was inscribed on the forehead of every person admitted into the Mysteries of Mithras. When a king was initiated into the Egyptian Mysteries, the TAU was placed against his lips. It was tattooed upon the bodies of the candidates in some of the American Indian Mysteries. To the Qabbalist, the TAU stood for heaven and the Pythagorean tetractys. The Caduceus of Hermes was an outgrowth of the TAU cross. (See Albert Pike.)

The Crux Ansata

The second type was that of a T, or TAU, cross surmounted by a circle, often foreshortened to the form of an upright oval. This was called by the ancients the Crux Ansata,

or the cross of life. It was the key to the Mysteries of antiquity and it probably gave rise to the more modern story of St. Peter’s golden key to heaven. In the Mysteries of Egypt the candidate passed through all forms of actual imaginary dangers, holding above his head the Crux Ansata, before which the powers of darkness fell back abashed. The student is reminded of the words In hoc signo vinces.

The TAU form of the cross is not unlike the seal of Venus, as Richard Payne Knight has noted. He states: “The cross in this form is sometimes observable on coins, and several of them were found in a temple of Serapis [the Serapeum], demolished at the general destruction of those edifices by the Emperor Theodosius, and were said by the Christian antiquaries of that time to signify the future life.”

THE CRUX ANSATA.

Both the cross and the circle were phallic symbols, for the ancient world venerated the generative powers of Nature as being expressive of the creative attributes of the Deity. The Crux Ansata, by combining the masculine TAU with the feminine oval, exemplified the principles of generation.

Augustus Le Plongeon, in his Sacred Mysteries Among the Mayas and Quiches,

notes that the Crux Ansata, which he calls The

Key to the Nile and the Symbol of Symbols,

either in its complete form or as a simple TAU, was to be seen adorning the breasts of statues and bas-reliefs at Palenque, Copan, and throughout Central America. He notes that it was always associated with water; that among the Babylonians it was the emblem of the water gods; among the Scandinavians, of heaven and immortality; and among the Mayas, of rejuvenation and freedom from physical suffering.

Concerning the association of this symbol with the waters of life,

Count Goblet d’Alviella, in his Migration of Symbols,

calls attention to the fact that an instrument resembling the Crux Ansata and called the Nilometer

was used by the ancient Egyptians for measuring and regulating the inundations of the river Nile. It is probable that this relationship to the Nile caused it to be considered the symbol of life, for Egypt depended entirely upon the inundations of this river for the irrigation necessary to insure sufficient crops. In the papyrus scrolls the Crux Ansata is shown issuing from the mouths of Egyptian kings when they pardoned enemies, and it was buried with them to signify the immortality of the soul. It was carried by many of the gods and goddesses and apparently signified their divine benevolence and life-giving power. The Cairo Museum contains a magnificent collection of crosses of many shapes, sizes, and designs, proving that they were a common symbol among the Egyptians.

The Roman and Greek Catholic Crosses

The third form of the cross is the familiar Roman or Greek type, which is closely associated with the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, although it is improbable that the cross used resembled its more familiar modern form. There are unlimited subvari- eties of crosses, differing in the relative proportions of their vertical and horizontal sections. Among the secret orders of different generations we find compounded crosses, such as the triple TAU in the Royal Arch of Freemasonry and the double and triple crosses of both Masonic and Roman Catholic symbolism.

To the Christian the cross has a twofold significance. First, it is the symbol of the death of his Redeemer, through whose martyrdom he feels that he partakes of the glory of God; secondly, it is the symbol of humility, patience, and the burden of life. It is interesting that the cross should be both a symbol of life and a symbol of death. Many nations deeply considered the astronomical aspect of religion, and it is probable that the Persians, Greeks, and Hindus looked upon the cross as a symbol of the equinoxes and the solstices, in the belief that at certain seasons of the year the sun was symbolically crucified upon these imaginary celestial angles.

The fact that so many nations have regarded their Savior as a personification of the sun globe is convincing evidence that the cross must exist as an astronomical element in pagan allegory. Augustus Le Plongeon believed that the veneration for the cross was partly due to the rising of a constellation called the Southern

Cross, which immediately preceded the annual rains, and as the natives of those latitudes relied wholly upon these rains to raise their crops, they viewed the cross as an annual promise of the approaching storms, which to them meant life.

There are four basic elements (according to both ancient philosophy and modern science), and the ancients represented them by the four arms of the cross, placing at the end of each arm a mysterious Qabbalistic creature to symbolize the power of one of these elements. Thus, they symbolized the element of earth by a bull; water by a scorpion, a serpent, or an eagle; fire by a lion; and air by a human head surrounded by wings. It is significant that the four letters inscribed upon parchment (some say wood) and fastened to the top of the cross at the time of the crucifixion should be the first letters of four Hebrew words which stand for the four elements: “Iammin

, the sea or water; Nour,

fire; Rouach,

the air; and lebeschah,

the dry earth.” (See Morals and Dogma,

by Albert Pike.)

That a cross can be formed by opening or unfolding the surfaces of a cube has caused that symbol to be associated with the earth. Though a cross within a circle has long been regarded as a sign of the planet Earth, it should really be considered as the symbol of the composite element earth, since it is composed of the four triangles of the elements. For thousands of years the cross has been identified with the plan of salvation for humanity The elements—salt, sulphur, mercury, and Azoth—used in making the Philosopher’s Stone in Alchemy, were often symbolized by a cross. The cross of the four cardinal angles also had its secret significance, and Masonic parties of three still go forth to the four cardinal points of the compass in search of the Lost Word.

The material of which the cross was formed was looked upon as being an essential element in its symbolism. Thus, a golden cross symbolized illumination; a silver cross, purification; a cross of base metals, humiliation; a cross of wood, aspiration. The fact that among many nations it was customary to spread the arms in prayer has influenced the symbolism of the cross, which, because of its shape, has come to be regarded as emblematic of the human body. The four major divisions of the human structure—bones, muscles, nerves, and arteries—are considered to have contributed to the symbolism of the cross. This is especially due to the fact that the spinal nerves cross at the base of the spine, and is a reminder that “Our Lord was crucified also in Egypt.”

Man has four vehicles (or mediums) of expression by means of which the spiritual Ego contacts the external universe: the physical nature, the vital nature, the emotional nature, and the mental nature. Each of these partakes in principle of one of the primary elements, and the four creatures assigned to them by the Qabbalists caused the cross to be symbolic of the compound nature of man.

The Crucifixion—A Cosmic Allegory

Saviors unnumbered have died for the sins of man and by the hands of man, and through their deaths have interceded in heaven for the souls of their executioners. The martyrdom of the God-Man

and the redemption of the world through His blood has been an essential tenet of many great religions. Nearly all these stories can be traced to sun worship, for the glorious orb of day is the Savior who dies annually for every creature within his universe, but year after year rises again victorious from the tomb of winter. Without doubt the doctrine of the crucifixion is based upon the secret traditions of the Ancient Wisdom; it is a constant reminder that the divine nature of man is perpetually crucified upon the animal organism. Certain of the pagan Mysteries included in the ceremony of initiation the crucifixion of the candidate upon a cross, or the laying of his body upon a cruciform altar. It has been claimed that Apollonius of Tyana (the Antichrist) was initiated into the Arcanum of Egypt in the Great Pyramid, where he hung upon a cross until unconscious and was then laid in the tomb (the coffer) for three days. While his body was unconscious, his soul was thought to pass into the realms of the immortals (the place of death). After it had vanquished death (by recognizing that life is eternal) it returned again to the body, which then rose from the coffer, after which he was hailed as a brother by the priests, who believed that he had returned from the land of the dead. This concept was, in substance, the teaching of the Mysteries.

The Crucified Saviors

The list of the deathless mortals who suffered

for man that he might receive the boon of eternal life is an imposing one. Among those connected historically or allegorically with a crucifixion are Prometheus, Adonis, Apollo, Atys, Bacchus, Buddha, Christna, Horus, Indra, Ixion, Mithras, Osiris, Pythagoras, Quetzalcoatl, Semiramis, and Jupiter. According to the fragramentary accounts extant, all these heroes gave their lives to the service of humanity and, with one or two exceptions, died as martyrs for the cause of human progress. In many mysterious ways the manner of their death has been designedly concealed, but it is possible that most of them were crucified upon a cross or tree. The first friend of man, the immortal Prometheus, was crucified on the pinnacle of Mount Caucasus, and a vulture was placed over his liver to torment him throughout eternity by clawing and rending his flesh with its talons. Prometheus disobeyed the edict of Zeus by bringing fire and immortality to man, so for man he suffered until the coming of Hercules released him from his ages of torment.

Concerning the crucifixion of the Persian Mithras, J. P. Lundy has written: “Dupuis tells us that Mithra was put to death by crucifixion, and rose again on the 25th of March. In the Persian Mysteries the body of a young man, apparently dead, was exhibited, which was feigned to be restored to life. By his sufferings he was believed to have worked their salvation, and on this account he was called their Savior. His priests watched his tomb to the midnight of the vigil of the 25th of March, with loud cries, and in darkness; when all at once the light burst forth from all parts, the priest cried, Rejoice, O sacred initiated, your God is risen. His death, his pains, and sufferings, have worked your salvation.” (See Monumental Christianity.)

In some cases, as in that of the Buddha, the crucifixion mythos

must be taken in an allegorical rather than a literal sense, for the manner of his death has been recorded by his own disciples in the Book of the Great Decease.

However, the mere fact that the symbolic reference to death upon a tree has been associated with these heroes is sufficient to prove the universality of the crucifixion story.

The East Indian equivalent of Christ is the immortal Christna, who, sitting in the forest playing his flute, charmed the birds and beasts by his music. It is supposed that this divinely inspired Savior of humanity was crucified upon a tree by his enemies, but great care has been taken to destroy any evidence pointing in that direction. Louis Jacolliot, in his book The Bible in India,

thus describes the death of Christna: “Christna understood that the hour had come for him to quit the earth, and return to the bosom of him who had sent him. Forbidding his disciples to follow him, he went, one day, to make his ablutions on the banks of the Ganges * * *. Arriving at the sacred river, he plunged himself three times therein, then, kneeling, and looking to heaven, he prayed, expecting death. In this position he was pierced with arrows by one of those whose crimes he had unveiled, and who, hearing of his journey to the Ganges, had, with a strong troop, followed with the design of assassinating him * * *. The body of the God-man was suspended to the branches of a tree by his murderer, that it might become the prey of vultures. News of the death having spread, the people came in a crowd conducted by Ardjouna, the dearest of the disciples of Christna, to recover his sacred remains. But the mortal frame of the redeemer had disappeared—no doubt it had regained the celestial abodes * * * and the tree to which it had been attached had become suddenly covered with great red flowers and diffused around it the sweetest perfume.” Other accounts of the death of Christna declare that he was tied to a cross-shaped tree before the arrows were aimed at him.

The existence in Moor’s The Hindu Pantheon

of a plate of Christna with nail wounds in his hands and feet, and a plate in Inman’s Ancient Faiths

showing an Oriental deity with what might well be a nail hole in one of his feet, should be sufficient motive for further investigation of this subject by those of unbiased minds. Concerning the startling discoveries which can be made along these lines, J. P. Lundy in his Monumental Christianity

presents the following information: “Where did the Persians get their notion of this prophecy as thus interpreted respecting Christ, and His saving mercy and love displayed on the cross? Both by symbol and actual crucifix we see it on all their monuments. If it came from India, how did it get there, except from the one common and original centre of all primitive and pure religion? There is a most extraordinary plate, illustrative of the whole subject, which representation I believe to be anterior to Christianity. It is copied from Moor’s Hindu Pantheon,

not as a curiosity, but as a most singular monument of the crucifixion. I do not venture to give it a name, other than that of a crucifixion in space.

* * * Can it be the Victim-Man, or the Priest and Victim both in one, of the Hindu mythology, who offered himself a sacrifice before the worlds were? Can it be Plato’s second God who impressed himself on the universe in the form of the cross? Or is it his divine man who would be scourged, tormented, fettered, have his eyes burnt out; and lastly, having suffered all manner of evils, would be crucified?

Plato learned his theology in Egypt and the East, and must have known of the crucifixion of Krishna, Buddha, Mithra [et al].

At any rate, the religion of India had its mythical crucified victim long anterior to Christianity, as a type of the real one [Pro Deo et Ecclesia!

], and I am inclined to think that we have it in this remarkable plate.”

The modern world has been misled in its attitude towards the so-called pagan deities, and has come to view them in a light entirely different from their true characters and meanings. The ridicule and slander heaped by Christendom upon Christna and Bacchus are excellent examples of the persecution of immortal principles by those who have utterly failed to sense the secret meaning of the allegories. Who was the crucified man of Greece, concerning whom vague rumors have been afloat? Higgins thinks it was Pythagoras, the true story of whose death was suppressed by early Christian authors because it conflicted with their teachings. Was it true also that the Roman legionaries carried on the field of battle standards upon which were crosses bearing the crucified Sun Man?

The Crucifixion of Quetzalcoatl

One of the most remarkable of the crucified World Saviors is the Central American god of the winds, or the Sun, Quetzalcoatl, concerning whose activities great secrecy was maintained by the Indian priests of Mexico and Central America. This strange immortal, whose name means feathered snake,

appears to have come out of the sea, bringing with him a mysterious cross. On his garments were embellished clouds and red crosses. In his honor, great serpents carved from stone were placed in different parts of Mexico.

THE CRUCIFIXION OF QUETZALCOATL. (FROM THE CODEX BORGIANUS.)

Lord Kingsborough writes: “May we not refer to the seventy-third page of the Borgian MS., which represents Quexalcoatl both crucified, and as it were cut in pieces for the cauldron, and with equal reason demand, whether anyone can help thinking that the Jews of the New World [Lord Kingsborough sought to prove that the Mexicans were descendants of the Jews] applied to their Messiah not only all the prophecies contained in the Old Testament relating to Christ, but likewise many of the incidents recorded of him in the Gospels.”

The cross of Quetzalcoatl became a sacred symbol among the Mayas, and according to available records the Maya Indian angels had crosses of various pigments painted on their foreheads. Similar crosses were placed over the eyes of those initiated into their Mysteries. When Cortez arrived in Mexico, he brought with him the cross. Recognizing this, the natives believed that he was Quetzalcoatl returned, for the latter had promised to come back in the infinite future and redeem his people.

In Anacalypsis,

Godfrey Higgins throws some light on the cross and its symbolism in America: “The Incas had a cross of very fine marble, or beautiful jasper, highly polished, of one piece, three-fourths of an ell in length, and three fingers in width and thickness. It was kept in a sacred chamber of a palace, and held in great veneration. The Spaniards enriched this cross with gold and jewels, and placed it in the cathedral of Cuzco. Mexican temples are in the form of a cross, and face the four cardinal points. Quexalcoatl is represented in the paintings of the Codex Borgianus nailed to the cross. Sometimes even the two thieves are there crucified with him. In Vol. II. plate 75, the God is crucified in the Heavens, in a circle of nineteen figures, the number of the Metonic cycle. A serpent is depriving him of the organs of generation. In the Codex Borgianus, (pp. 4, 72, 73, 75,) the Mexican God is represented crucified and nailed to the cross, and in another place hanging to it, with a cross in his hands. And in one instance, where the figure is not merely outlined, the cross is red, the clothes are coloured, and the face and hands quite black. If this was the Christianity of the German Nestorius, how came he to teach that the crucified Savior was black? The name of the God who was crucified was Quexalcoatl.”

The crucifixion of the Word in space, the crucifixion of the dove often seen in religious symbolism—both of these are reminders of pagan overshadowing. The fact that a cross is formed by the spread wings of a bird in relation to its body is no doubt one of the reasons why the Egyptians used a bird to symbolize the immortal nature of man, and often show it hovering over the mummified body of the dead and carrying in one of its claws the sign of life and in the other the sign of breath.

The Nails of the Passion

The three nails of the Passion have found their way into the symbolism of many races and faiths. There are many legends concerning these nails. One of these is to the effect that originally there were four nails, but one was dematerialized by a Hebrew Qabbalist and magician just as they were about to drive it through the foot of the Master. Hence it was necessary to cross the feet. Another legend relates that one of the nails was hammered into a crown and that it still exists as the imperial diadem of a European house. Still another story has it that the bit on the bridle of Constantine’s horse was a Passion nail. It is improbable, however, that the nails were made of iron, for at that time it was customary to use sharpened wooden pegs. Hargrave Jennings, in his Rosicrucians, Their Rites and Mysteries,

calls attention to the fact that the mark or sign used in England to designate royal property and called the broad arrow

is nothing more nor less than the three nails of the crucifixion grouped together, and that by placing them point to point the ancient symbol of the Egyptian TAU cross is formed.

In his Ancient Freemasonry,

Frank C. Higgins reproduces the Masonic apron of a colossal stone figure at Quirigua, Guatemala. The central ornament of the apron is the three Passion nails, arranged exactly like the British broad arrow. That three nails should be used to crucify the Christ, three murderers to kill CHiram Abiff, and three wounds to slay Prince Coh, the Mexican Indian Osiris, is significant.

C. W. King, in his Gnostics and Their Remains,

thus describes a Gnostic gem: “The Gnostic Pleroma, or combination of all the Æons [is] expressed by the outline of a man holding a scroll * * *. The left hand is formed like three bent spikes or nails;

unmistakably the same symbol that Belus often holds in his extended hand on the Babylonian cylinders, afterwards discovered by the Jewish Cabalists in the points of the letter Shin,

and by the mediaeval mystics in the Three Nails of the Cross.” From this point Hargrave Jennings continues King’s speculations, noting the resemblance of the nail to an obelisk, or pillar, and that the Qabbalistic value of the Hebrew letter Shin,

or Sin,

is 300, namely, 100 for each spike.

The Passion nails are highly important symbols, especially when it is realized that, according to the esoteric systems of culture, there are certain secret centers of force in the palms of the hands and in the soles of the feet.

The driving of the nails and the flow of blood and water from the wounds were symbolic of certain secret philosophic practices of the Temple. Many of the Oriental deities have mysterious symbols on the hands and feet. The so-called footprints of Buddha are usually embellished with a magnificent sunburst at the point where the nail pierced the foot of Christ.

In his notes on the theology of Jakob Böhme, Dr. Franz Hartmann thus sums up the mystic symbolism of the crucifixion: “The cross represents terrestrial life, and the crown of thorns the sufferings of the soul within the elementary body, but also the victory of the spirit over the elements of darkness. The body is naked, to indicate that the candidate for immortality must divest himself of all claims for terrestrial things. The figure is nailed to the cross, which symbolizes the death and surrender of the self-will, and that it should not attempt to accomplish anything by its own power, but merely serve as an instrument wherein the Divine will is executed. Above the head are inscribed the letters: I. N. R. J. whose most important meaning is: In Nobis Regnat Jesus (Within ourselves reigns Jesus). But this signification of this inscription can be practically known only to those who have actually died relatively to the world of desires, and risen above the temptation for personal existence; or, to express it in other words, those who have become alive in Christ, and in whom thus the kingdom of Jesus (the holy love-will issuing from the heart of God) has been established.” One of the most interesting interpretations of the crucifixion allegory is that which identifies the man Jesus with the personal consciousness of the individual. It is this personal consciousness that conceives of and dwells in the sense of separateness, and before the aspiring soul can be reunited with the ever-present and all-pervading Father this personality must be sacrificed that the Universal Consciousness may be liberated.