In the years that followed the last battle of Kawanakajima the rivalry and mistrust between Shingen and Kenshin ensured that the war continued by other means. In 1565 Kenshin revealed in a letter of 19 August to a castle commander in Kozuke province that he still wished to invade Shinano to liberate the province, but that ‘times had changed’. Fighting between them now went on in neighbouring provinces as each assisted his enemy’s enemies.

The siege of Minowa in 1566 is one outstanding example of this policy. Minowa castle in Kozuke was defended fiercely by a strong retainer of the Uesugi called Nagano Narimasa. For this reason Takeda Shingen had left it well alone, but when Narimasa died, fearful lest the Takeda should take advantage of this the Nagano followers kept his death secret for as long as possible while his heir Narimori consolidated his position.

The Takeda soon realised what had happened and launched their attack in 1566. The great swordsman Kamiizumi Hidetsuna took part in the defence of Minowa with the young heir leading at the front. Attack after attack was repulsed, with the action characterised almost exclusively by hand-to-hand combat, helped by some ingenious defence works that included piles of logs released beside the gate when an attack took place. Finally Hidetsuna took the fight to the Takeda and sallied out of the castle in a bold surge. The Takeda became demoralised, but then fate took a hand, for in another sally by the defenders the young heir Narimori was cut down and killed, and this time there was no opportunity to keep a commander’s death secret. The Takeda seized upon this huge psychological weapon, and the shattered defenders were forced to sue for peace.

Another scene from the re-enactment of Uesugi Kenshin’s departure for war at Yonezawa. Here the actor playing Kenshin is shown in a vivid white headcowl as he makes an offering at a Shinto shrine.

The head mound at Hachimanbara, where are interred the heads of the samurai that were taken during the fourth battle of Kawanakajima.

In 1568 the mountains and valleys on the border area between Echigo and Shinano were to echo to the sound of fighting for one last time. With Kawanakajima now firmly established as a Takeda island, the Uesugi sphere of influence in Shinano was confined to its northern tip. In 1567 the Ichikawa family, based north of Iiyama castle, declared for Shingen, and Shingen gave orders for the restoration of Nagahama castle on the border. This former Shimazu possession received extensive repairs and a castle town was created around it. Nagahama now provided a rival to Kenshin’s Iiyama.

After this, Shingen devised a complex scheme. In 1568 he worked on the daimyo of Etchu province to unite against Kenshin. Kenshin retaliated by invading Etchu, but while he was absent Shingen won over to his side Kenshin’s renowned general Honjo Shigenaga. Takeda Shingen judged that the time was ripe to take advantage of Kenshin’s problems and invade Echigo. Even if he could not reach Kasugayama, merely to wipe off the map Iiyama and the other border outposts would bring his long Shinano campaign to a successful conclusion after 26 years.

So Shingen led an army to Kawanakajima for the last time. He advanced to his secure and trusty base of Kaizu castle, from where on 3 August 1568 he sent a detachment forward to attack Iiyama. While they were on their way along the Chikumagawa route Shingen led his main body even further into the Togakushi/Iizuna than he had dared go during the glory days of 1553–64. From Togakushi he entered his new outpost of Nagahama castle, from where he could easily invade Echigo.

Kenshin responded immediately to the twin threats by sending reinforcements to Iiyama castle and to his newly built fortress of Sekida on the pass of the same name that had provided his means of entry into Shinano on so many previous occasions. In this Uesugi Kenshin displayed great determination and a sensible order of precedence. He was not so preoccupied with resisting rebels in his own province that he would neglect an invasion from Shinano by Takeda Shingen.

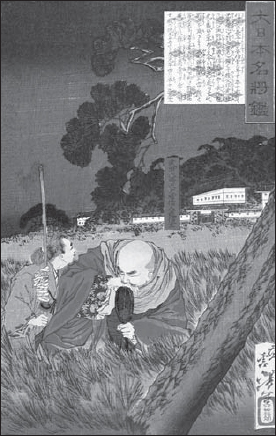

The death of Takeda Shingen at Noda in 1573. He was shot by a sniper from the walls of the castle.

The stage was set for another Uesugi advance down into the plains of northern Shinano and perhaps even a sixth battle of Kawanakajima. Times had changed for both protagonists, however, and the armies stayed on the border. There may not have been a sixth battle and the two commanders may not actually have been in Kawanakajima, but the stalemate that ensued with Takeda Shingen glaring down from Nagahama and Uesugi Kenshin glaring back at him from Iiyama differed only from the 1555 and 1564 scenarios in its precise location.

For Shingen it had been enough just to threaten Kenshin with an invasion. He was now almost literally sitting on the Echigo border, the monarch of all he surveyed in a southerly direction. He probably had no intention of attacking Kasugayama castle. Instead he had drawn a line in the snow to remind his rival of where they stood. After 26 years Shinano was his.

Kenshin too managed to satisfy himself with the inevitable situation. His border was secure, and he had long since given up his obsessive goal of seeking a final pitched battle with Shingen. Times had indeed changed, and both rivals knew that events occurring far off in the west were to alter the balance of power in Japan forever, and make the long Takeda/Uesugi rivalry seem a matter of little consequence. While Shingen and Kenshin were conducting their last eyeball-to-eyeball confrontation on the Shinano/Echigo border the up-and-coming daimyo Oda Nobunaga succeeded where every other daimyo since the Onin War had failed. He marched on Kyoto, secured the capital and set up his own nominee, Ashikaga Yoshiaki, as Shogun.

For Takeda Shingen in particular this meant a radical rethinking of his strategic position. No longer was it imperative upon him to head north towards the Sea of Japan. That part of the country was now an irrelevant backwater that could be left to Kenshin. The real seat of activity had shifted to the Pacific coast, from which landlocked Kai was separated by the territories of the mighty Hojo and another young daimyo allied to Oda Nobunaga called Tokugawa Ieyasu. Thus it was that Takeda Shingen’s new policy saw him heading south in 1569 for an unsuccessful siege of the Hojo’s Odawara castle. It was a dismal failure, and to add insult to injury the Hojo samurai ambushed him at the battle of Mimasetoge (Mimase Pass) on his return.

Takeda Shingen had much more success when he turned his attentions towards Tokugawa territory. At Mikata ga Hara in 1572 he won a cavalry victory in classic Takeda style but failed to consolidate his triumph by capturing Hamamatsu castle. He renewed his attempts to destroy Tokugawa Ieyasu when the snows melted the following year. The Takeda laid siege to Ieyasu’s castle of Noda in Mikawa province and were very successful, so the garrison prepared for a honourable surrender. According to an enduring legend the defenders, knowing that their end was near, decided to dispose of their stocks of sake (rice wine) in the most appropriate manner. The Takeda samurai in the besieging camp could hear the noise of their drunken celebrations and took note of one Tokugawa samurai who was playing a flute rather well. Takeda Shingen approached the ramparts to hear the tune, and a vigilant guard, who was less drunk than his companions, took an arquebus and put a bullet through the great daimyo’s head. The death of their beloved leader was kept secret for as long as the Takeda could manage, but the news eventually leaked out.

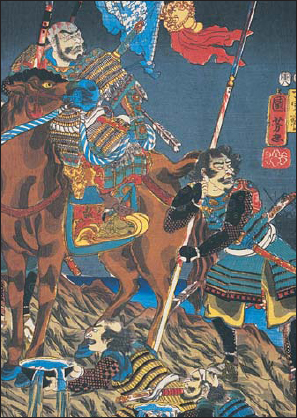

The death of Yamamoto Kansuke at Kawanakajima. Although handicapped by having only one good leg and one good eye, Yamamoto Kansuke had risen to be Shingen’s right-hand man and was nearly 70 years old at Kawanakajima. He accepted full responsibility for the disaster that his error of judgement had brought upon them, and resolved to make amends by dying like a true samurai.

Takeda Yoshinobu, who had fought so bravely at Kawanakajima, had died young in 1567, so Shingen was succeeded by his able but headstrong son Takeda Katsuyori. He was the son of the lady of Suwa whom Shingen had seized in one of his earliest incursions into Shinano province. To many people she had brought a curse on the family, and their doom would be accomplished through the son she had born to Shingen. This prophecy was to come true all too soon in 1575 on the battlefield of Nagashino. Katsuyori’s defeat marked the end of the Takeda as a military force of any consequence in central Japan. The clan lingered on for seven more years, but never again would a Takeda army leave Kai to bring war to its neighbours.

As for Uesugi Kenshin, still the nominal ‘lord of the Kanto’, he battled on against the Hojo on one side and Oda Nobunaga on the other. In fact Kenshin inflicted upon Oda Nobunaga one of the few defeats of his career. This was the night battle of Tedorigawa in 1577, a considerable victory gained by using a manoeuvre that had echoes of Kenshin’s crossing of the Chikumagawa at Amenomiya at the fourth battle of Kawanakajima in 1561.

Kenshin now looked destined to be one of the few daimyo who would have the resources and the skills to oppose the seemingly irresistible rise of Oda Nobunaga. But a year later a servant heard cries from inside Kenshin’s lavatory and found his lord dying and unable to speak. He had probably had a stroke, but his death was so fortuitous for Oda Nobunaga that ninja were suspected. On his death the Uesugi domains were divided between his heir Kagetora, the son of Hojo Ujiyasu whom the celibate Kenshin had adopted, and his nephew Kagekatsu, son of his brother-in-law Nagao Masakage.

The rivals of the Uesugi were already gathering like vultures, and in a scenario that could not have been any more favourable to their enemies the two cousins went to war with each other. Within a short space of time Uesugi Kagetora was dead. Kagekatsu was now the undisputed lord of the Uesugi, but their power had been broken forever.

By the early 1580s, when the territories of Takeda and Uesugi had ceased to mean anything in the context of Japanese politics, the Kawanakajima area became a backwater in more ways than one. Ueda, the town just to the south of the battlefield, became the seat of the Sanada family, who were descended from one of Shingen’s Twenty-Four Generals. It grew in importance because it lay on the Nakasendo road. This was one of the two main highways between Kyoto and Edo, the city now called Tokyo that became the capital of the Tokugawa family, who had destroyed the Takeda in 1582.

During the Tokugawa Period, Kawanakajima as battlefield gave way to Kawanakajima as myth. The five battles became a popular topic for woodblock printmakers during the 19th century and depictions of Shingen and Kenshin sold in their thousands. Because both families had died out there was no danger of embarrassing the Tokugawa government, so the censors left pictures of Kawanakajima alone. As for the site of the great encounters, the plain was farmed and yielded much fruit. So remote was the area that Matsumoto castle (the former Fukashi) was fortunately spared the loyal and modernising demolition mania that afflicted so much of Japan in the late 19th century and remains to this day the oldest extant tower keep in arguably the most beautiful castle in Japan.

Following the Meiji Restoration, Shinano province became Nagano Prefecture. Not many years later the mountains beyond Matsumoto that had provided the backdrop to the Kawanakajima campaigns were ‘discovered’ by an English missionary called Walter Weston. He christened them the ‘Japan Alps’ and introduced the modern concept of mountaineering to Japan. While Victorian enthusiasts hiked along the paths once trodden by Shingen’s raiders the great Zenkoji temple continued to display the exact copy of Japan’s first Buddhist statue every seven years. Meanwhile the city of Nagano gradually spread around it. Both the Susohanagawa and Chikumagawa changed their courses, while down on the plain modern roads and railways began to cut their way across what had once been the site of five battles. A century later the cross-country skiers of the 1998 Winter Olympics raced each other through the passes that had echoed to the Takeda/Uesugi border wars. Only the Saigawa stayed roughly where it had been all those centuries ago, still creating with the help of the Chikumagawa a curious triangular island between them that would always bear the stirring name of Kawanakajima.