In the 1950s the heist film came into its own. There were a spate of not-so-memorable works from this era, but in the hands of more deft directors, the genre began to express idiosyncratic concerns across dramatic and comic modes, as in Jacques Becker’s taut elegy to an ageing gangster, Touchez pas au grisbi (1954), or Alexander Mackendrick’s splendid farce The Ladykillers. Moreover, the heist film hit two pivotal points that gave the genre a broader appeal to audiences: eliciting sympathy for the criminal gang and experimenting with widescreen and colour formats. In the first case, it was never inevitable the heist would continue to focus on likeable characters. Richard Fleischer’s Armored Car Robbery (1950) showcased a violent, precision-engineered robbery whose ‘militarisation of gang life’ recommend it as ‘the most typical of the heist sub-genre’ (Mason 2002: 99–100), just as his later work Violent Saturday (1955) presented the most unsympathetic of criminals. Samuel Fuller’s House of Bamboo (1955), meanwhile, the first Hollywood studio film ever made in Japan, also fore-grounded violence without sympathy for the gang as a whole.

More indicative of the shift was how Phil Karlson’s dark, anti-heroic

Kansas City Confidential (1952) differed drastically from his next film,

Five Against the House (1955), in which the audience sides with four college students motivated by the intellectual challenge of robbing a Reno casino. On the other hand, Fleischer’s

Violent Saturday and Fuller’s

House of Bamboo also anticipated the noir heist’s symbolic move away from its B-movie roots and innovated by experimenting with emerging wide-screen and colour formats (Bordwell 2008: 321). As important a factor as the audience’s reception of sympathetic thieves, then, Technicolor and CinemaScope presaged the inevitable inclination towards mainstream tastes before the colourful caper fantasies of the 1960s.

Most significant to the heist film’s history during this era, however, was its transformation into an allegory for collaborative creative activity. This arises in three foundational noir films from the middle of the decade – Jules Dassin’s Rififi, Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing, and Jean-Pierre Melville’s Bob le Flambeur – but also in two satirical works that bookend the decade – Charles Crichton’s The Lavender Hill Mob and Mario Monicelli’s Big Deal on Madonna Street. This chapter will examine the noir heist first before moving on to the comedies, though it should be evident each set profoundly shaped the genre. Dassin, Kubrick and Melville borrowed John Huston’s sociological interest in working class people or professional criminals living on society’s margins. The tragic outcome of their films – their ‘enigmatic fatal strategy’ (Telotte 1996: 163) – hones the post-war pessimism of film noir (see chapter one) in the face of a new corporate era, a pessimism abandoned by most post-1980 heists that induces us to characterise this manifestation of the genre as a noir heist (see Telotte’s two phases of the noir caper, 1996: 165–6). Yet despite the amusing tone and lack of violence of Crichton’s and Monicelli’s films, they share in common with these noir heists a pleasure in failure. These films are remarkable for energising the functional message of the heist by fully realising the genre’s potential as subtle mainstream parables about aesthetic and economic autonomy with a modernist edge that celebrates failure as the ineluctable end of artistic endeavours. Allistair Rolls and Deborah Walker’s observation about Dassin’s Rififi applies equally to the genre at large: ‘Rififi is notable for its emphasis on crime as work and the role of the skill and cooperation in transforming labour into art. In this … Rififi’s heist cries out to be read as an allegory of the film-making process itself as collective craftsmanship’ (2009: 154). These films each separately exploited the generic potential of a transgressive act – robbery – that lends itself particularly well to the sublimated desire for both economic and aesthetic independence, a potentiality of the form that remains a constant into the twenty-first century.

Contexts for the Mid-1950s Noir Heist

The noir heist’s entangled and sometimes contradictory strands in the 1950s may be interpreted in light of three interrelated contexts: the imminent demise of film noir at the very moment critical attention begins to recognise it as a distinctive film idiom operating both within and against Hollywood; the concomitant emergence of auteurism, the influential theory of film authorship championed by critics at the French film magazine Cahiers du cinéma; and the transatlantic exchange of ideas and forms of several heists of the period. James Naremore points out that auteurism and film noir worked in parallel: ‘film noir was a collective style operating within and against the Hollywood system; and the auteur was an individual stylist who achieved freedom over the studio through existential choice’ (1998: 26). The freedom or artistic autonomy embedded in the films examined in this chapter mark this moment as a watershed in the genre’s history and link the modest aspirations of the noir heist (even when comic) to modernism, the cultural current of the first half of the twentieth century, inflected by a wariness towards commodity culture’s effect on artists similar to what we find in a more restrictive sense in auteurism.

The major noir heists I examine in this chapter were released between 1954 and 1956, a felicitous moment in the history of film criticism when the concept of the

auteur arose in French film criticism. François Truffaut’s 1954 landmark essay in the

Cahiers du cinéma, ‘A Certain Tendency in French Cinema’, circulated his ‘

politique des auteurs’, a theory that celebrated the individual ‘author’ of a film. Truffaut and his fellow critics admitted that cinema, and Hollywood cinema in particular, was a mass art. But they venerated those directors and screenwriters who put signature touches on their industrial products. The critic Jean-Luc Comolli, for example, railed against the genre film spectator’s ‘conditioned’ desire ‘for familiar forms, recognized patterns, the whole homogenized apparatus’ (1986: 211), while praising those auteurs that ‘sought to opt out of Hollywood, or to subvert it’ (1986: 212). The auteur debate raised questions about the nature of film as a commercial art, and the status of its practitioners within and without the system. The

politique des auteurs debate matters here because it evokes the

independent stance assumed by those filmmakers working in and around, but also subversively against, Hollywood. The thematics of the heist in the mid-1950s and this critical discourse, while not causally linked, are substantively related.

Auteur theory’s wariness towards institution and commerce echoes similar concerns expressed by the older and more far-reaching agenda of aesthetic modernism (described briefly at the end of chapter one). The avant-garde practices of European modernism are characterised by a sharpened sense of form and medium, a desire for aesthetic autonomy and self-reflective attention to acts of artistic creation. Film noir, too, including the noir heist, could also be imagined as an attempt ‘to define artistic value in ways that … maximize’ filmmakers’ control over their art, and ‘to make specific claims about what art is or has been’ (Adamson 2007: 18). Film noir arose from within popular media but reacted to the very same commodity foe as did high-culture modernists. Dassin, Kubrick and Melville were in their own ways wary of the studio system’s all-consuming power and worked ‘as independent producers outside of – and in opposition to – the Hollywood establishment’ (Kaminsky 1974: 76). Dassin was shunned by Hollywood as a result of House Un-American Activities Committee suspicions and fled to England, France and eventually Greece. Kubrick, an East Coast American like Dassin, chose to work on the edge of Hollywood. Melville could admire America’s B-film culture from a safe distance in Paris, where he remained resolutely aloof from the French studio system. The autonomy these filmmakers carefully guarded – ‘a certain estrangement from the centres of movie industry power’ (Naremore 2008: 1) – cannot be overemphasised, as it aligns with the very thematics of independence in their heist plots.

Just as modernism was a transatlantic phenomenon, so too was the heist’s consolidation into a social and aesthetic parable. Although the noir heist may have an American patent, the sub-genre’s full realisation benefitted from a French-American collaboration (and a British twist, once we include

The Lavender Hill Mob). As Ginette Vincendeau reminds us, ‘noir is also a French word’: film noir borrows something of its everyday environments and the ‘ordinariness’ of its characters from 1930s French Poetic Realism (1992: 57). James Naremore adds that postwar French intellectuals essentially ‘invented the American film noir … because local conditions predisposed them to view Hollywood in certain ways’ (1998: 13). Rolls and Walker suggest that the ‘constant communication and transference’ between the two traditions, modernism and noir, formed a related response to the ‘psychological trauma of the Second World War and its aftermath’ (2009: 2). The two traditions also shared a suspicion of ‘capitalist-driven modernization’ (2009: 5) that differed from the technocratic policies and state-run markets of socialist states during this time, which may be why the heist is found more readily in western liberal democracies such as the United States, the United Kingdom and France. Though some French intellectuals feared the Americanisation of French cultural objects, no matter how Americanised the narrative syntax or directorial touch, the world portrayed was decidedly French. Instead of a flat transposition of forms, this cross-cultural encounter led to a congenial and ‘highly successful and influential generic matrix’ (Vincendeau 2003: 103). Modernist in spirit, several noir heists critique the corporatist, money-mongering compulsions of the new expansionism in effect on both sides of the Atlantic.

Jules Dassin: The Dark Work of Creation

Dassin’s adaptation adopts much of the coarseness of Auguste Le Breton’s source novel about the Paris

pègre (it was a title in Gallimard’s

Série noire), or criminal underground. Yet Dassin also pursued a modernist line of thinking, namely, the futility of any aesthetic project that seeks transcendence. One must aspire to break free, but

Rififi’s tragic ending hues to a Girardian formula, suggesting that desires between rival gangsters will inevitably lead to mimetic violence, and that Tony’s and the gang’s search for independence will ultimately fail. This has biographical resonance for Dassin as he was trying to find a place to pursue his art unhampered by the politics of the HUAC proceedings.

Rififi is ‘social noir’, a kind of noir film, as Rolls and Walker put it, that decries the ‘alienating excesses of free-market, consumer capitalism’ and expresses frustration over the failure of the New Deal that had promised to lead America out of the Depression into a progressive era (2009: 152). Having started in the working-class theatre milieu of New York, Dassin’s film combined a progressive social message with the theatrical milieu and pursuits of artists. But having fled the United States for France, he managed to convert a very small budget ($200,000), a set of B-list players, and drab location exteriors into a model heist that elegises manual and creative labour, thereby transforming failure into a triumphant paradigm for the heist. He did so by distilling Le Breton’s literary figures into graphic

leitmotifs, by representing the process of labour and violence as a mixture of choreographed physical exertion and inspired intellection, by transforming the lacklustre spaces of

bas-fonds Paris into a modernist tableau through an economical use of expressionism (Rolls and Walker 2009: 157), and by using sound judiciously to portray poetic creativity and mimesis.

Rififi’s main character Tony Le Stéphanois has an art. It is stealing. Fresh out of the prison, ageing ex-con Tony (Jean Servais) forms a team for one last job: to steal diamonds from a high-end jewellery store. It is a dangerous proposition because of the dishonorable criminals competing in the same marketplace for a share of the take: Pierre Grutter (Marcel Lupovici), who owns the L’Âge d’Or (‘Golden Age’) nightclub, and his drug addict brother, Rémi (Robert Hossein). Tony’s old flame, Mado (Marie Sabouret), has taken up with Grutter. Tony’s partners Jo the Swede (Carl Möhner) and Mario Ferrati (Robert Manuel) are married men who enjoy domestic satisfaction. Mario’s safecracking Italian friend, Cesar – played by Dassin himself, though he is credited as Perlo Vita – will betray the team, unintentionally, by divulging their plan to a lover, Grutter’s singer Viviane (Magali Noël).

Dassin maintained Le Breton’s image of the gangster’s eroding place in a new, post-war context without honour, even among thieves, but he also translated one of the novel’s figures into a central metaphor that underscores the value of manual labour. In Le Breton’s slang-laden novel, Tony catches a couple of cardsharps cheating. He tells one not to move his ‘mitts’ (

pognes) and another to keep his ‘claws’ (

griffes) off a gun, before Tony suddenly draws a gun from his own ‘fist’ (

poing) (1953: 18) and Jo riddles one in his

paluche (‘paw’) (1953: 18). Le Breton’s knack for the economy of dialogue comes in the French phrase ‘

pas de pognon, pas de cartes’ (‘no cash, no cards’) thrown in Tony’s face by one of the cardsharps.

Pognon is a metonym for ill-gotten money and derives from the French verb

empoigner, ‘to grab something with hand or fist (

poing)’. Le Breton’s title

Rififi is slang both for fire and hand-to-hand fighting, and by extension a firearm or handgun. The hand serves as a metonym for manual labour, craft and instrumental violence. The first thing Dassin presents on screen is men’s hands throwing cards and chips, smoking and gesticulating, finishing with a close-up of Tony’s hands holding losing cards. No faces, just hands. Later, during a sequence in which Grutter tortures Mario to learn the whereabouts of the diamonds, a low-angle medium shot captures Mario’s limp hand centred in the frame. Finally, the stunning symmetrical sequences in which Grutter captures Cesar and then Tony executes Cesar, are built around manual action. In the first, Grutter (out of frame) surprises Cesar in Viviane’s dressing room. A hand holding a gun comes into the right edge of the frame and gestures for Cesar to follow – Grutter is not in the frame, we hear an off-screen voice, then cut to a tracking POV of Cesar moving through the prop room until he is thrown into the frame and another hand reaches in from the left, shoving a diamond ring into his face. Dassin constructs a symmetrically parallel sequence later when Tony happens upon Cesar tied up at in the prop room at

L’Âge d’Or. Here Dassin uses the same tracking shot, this time from Tony’s vantage point looking towards Cesar through the doorway. As he exits the prop room, Tony executes Cesar. This mimetic, right-left counterpoint of threatening hands finds its full realisation in the final fire-fight between Grutter and Tony, in which Dassin’s shot compositions and editing might be characterised as ‘gun-line’ matches that aestheticise the work of death dialectically. Dassin distills the hand – also foregrounded in the manual labour of the robbery sequence – from Le Breton’s gristly prose into one of the film’s figurative or poetic grounds.

Grutter’s hand threatening Cesar in the prop room

The execution sequence is significant for its modernist theatricality. Dassin had the benefit of working with one of Europe’s finest production designers in Alexandre Trauner, whose highly adaptable career spanned from the silent period and Poetic Realist Films to the cinéma du look of the 1980s. Trauner claims that the film was not to have an ‘imaginary’ but rather a ‘quasi-documentary’ feel from footage taken in Paris streets (Berthomé 1988: 128). His triumph was the expressionist conversion of the nightclub’s prop room into a space redolent of the 1920s avant-garde: ‘Cesar is executed amid a bric-a-brac of surrealist symbols: naked mannequins evoking the ghosts of old comrades, masks and a guitar for dissimulation and “singing” betrayal, daisies for happy illusions and (broken) ideals’ (Rolls and Walker 2009: 155). In this fanciful mise-en-scène Trauner harmonised the theatricality of the nightclub with several latent aspects of theatricality of the film, notably in the central heist sequence.

Much has been written about the heist sequence, primarily because of its lack of dialogue or musical overlay. The ambient sounds of work are meaningful in and of themselves, because they draw our attention to the manual labour of these craftsmen. The robbery occupies a secondary place in Le Breton’s novel behind its seedy characters, and nowhere is process at issue. As Rolls and Walker rightly claim, ‘the dramatic intensity of the [robbery] sequence, still the quintessential reference in the genre, is wrought from an almost surgical attention to detail (the transformation of everyday objects into professional, precision tools), taut direction and camera work (cross-cutting between the closely framed action in the room, ticking clock on the wall, and the street below) and, of course, the Bressonian soundtrack, entirely without dialogue and music for 25 minutes’ (2009: 153). Rolls and Walker also emphasise the deep-focus group shots as a sign of Dassin’s attention to the collaborative work taking place before our eyes, an apt metaphor for ‘the role of skill and cooperation in transforming labour into [film] art’ (2009: 154). Thus, Dassin converts the robbery into the raison d’être of the film, the core aesthetic motivation.

I wish to extend Rolls and Walker’s insights by emphasising the per-formative and richly analogical aspect of the sequence. The heist unfolds as a stage spectacle and music concert – without music. The men work in concert, as if they were performing improvisatory jazz, with one working on a task – Jo methodically piercing through the floor, Tony on the alarm, Cesar on the safe – as others stand by ready with the next necessary tool, their movement interacting harmoniously. They have practiced and planned, but never before performed. Other analogies come to mind. The heist is indeed ‘surgical’: Cesar cuts into the safe as if into a body; Mario functions as a nurse by handing Cesar scalpel (screwdriver) and clamp. It is also a dance: the men’s gestures are choreographed as they move about and reposition themselves in relation to each other and the safe. The sequence never turns away from the attention to manual effort. Jo collapses into the chair after hours chipping away at the ceiling. We see the exertion in close-up as the other three gently lean the safe onto Jo’s back and then onto wooden blocks. And, of course, the final segment of Cesar rhythmically cutting through the safe’s back, intercut with shots of the ratchet, the tightly framed shots of the faces of Tony and Cesar, then of Jo and Mario in acute anticipation, as we hear the ratchet turn faster and faster, is a crescendo of energy and exertion leading to a climax of virile fulfillment – all without a second’s worth of music or dialogue.

Joe, Mario, Tony and Cesar labor as a team

Yet we fail to grasp the virtuosity of the heist sequence if we sever it from the entire sound-image economy of the film, especially the preparation montages, which function in concert with the theatrical work of the robbery. The music accompanying the initial practice-and-preparation montage effectively whisks the sequences along. George Auric’s score shifts between a playful and a modestly suspenseful tone, setting the spectrum of emotional response for the audience not merely for this sequence but for the film in its entirety. And before we ever enter the jewellery store, it too emphasises the talent of the work displayed, manual skills, intelligence and dexterity. From the street, Tony cases Mappin and Webb and the surrounding boutiques, while Jo jots down the comings and goings of the florist in a notebook. With Tony on the lookout and as Mario surreptitiously makes the imprint for the key, a light string and flute melody plays, with gentle brass, bass and woodwind accents. Significantly, as Mario finishes the copied key back in a workshop, the sound of a grinder run by Cesar in the background melds rhythmically with the string parts – the men are making music. Similar instrumentation continues throughout the montage, dipping occasionally into minor chords, and a brassier segment calling on timpani, flute and xylophone as the criminals test their escape in a car, until a crescendo completes the segment once Cesar reaches Mappin and Webb to determine which kind of alarm the store uses. Cesar’s visit is brief but almost as striking as the heist sequence. Certainly this segment adds to the work’s purity of medium. Unlike the previous sequences in the preparation montage, there is music without (heard) dialogue: a teasing flute and string intertwine while Cesar examines cigarette lighters before requesting to use a phone in the rear of the establishment. But what is unique in this ‘mimed sequence’ (Hayes 2006: 77) is that we also hear ambient sounds under the musical accompaniment – a female clerk’s shoes striking the floor, a male clerk in a creaky chair, and, most importantly, Cesar’s shuffling of bills. But the words mouthed by the clerk and Cesar remain unheard. Given the other diegetic sounds, this scene truly was played in mime! Gesture counts more than word; it works in conjunction with non-diegetic sound. Cesar slips into the back of the shop where, on the phone, he watches a clerk examining jewels, in a tightly framed low-angle medium two-shot, and glances around at the safe and alarm. The bass picks up, as does the volume, cymbals and drums clashing with the insert shot of the safe, brass sweeping everything away and a close up of the alarm. In these sequences, Dassin gives a nod to both theatre and silent film. What critics have failed to mention is that, differentially, it sets up the spectacular and performative nature of the central heist, which encodes the crime as an aesthetic act within the genre.

Graeme Hayes highlights the ‘professionalisation of criminality’ in Rififi (2006: 73). The criminals are trained craftsmen, working-class castoffs in a society turning increasingly towards technology for its salvation. The film ‘revels in the display of craftsmanship,’ an exemplary use of Murray Smith’s category of the ‘cinema of process’, and, for Truffaut, the film is ‘heroic, a celebration of the dignity of labor, its moral worth and social utility’ (quoted in Hayes 2006: 74). One might be tempted to differentiate between Cesar’s artificiality and the working-class efforts of the other gang members. But because Dassin juxtaposes Mario, Tony and Jo’s manual skill with Cesar’s mime, the latter’s playacting is necessarily associated with the manual effort of the former, while theirs is elevated to the status of stagecraft. The montage thus metaphorically fuses physical labour and art, shrewd professionalism and mimesis, crime and the aesthetic. As an elegy, it raises the status of the skilled labourer to that of artist.

As a final comment on process, I wish to address Tony’s particular genius as an innovator. Critics stress that because he uses a fire extinguisher to mute the alarm, he is not technologically oriented or the technology is outdated (presumably so as not to arouse the suspicion of censors). This may not be the fairest reading. Tony keeps running through possible solutions as the others look on, stumped as to what to do. Tony walks away from their objections, picks up a champagne bottle, and then looks over at the extinguisher on the wall, apparently realising the possibility of using compressed fluids that expand when exposed to air as a solution to disarming the device. I see three things here. First, it is Tony who comes up with the solution for the alarm – the team bears the burden for preparing and executing the plan, but Tony’s intelligence wins out. Second, it is a

technological solution, one that involves a simple transfer of knowledge from one domain to another. Third, the alarm sequence alone takes up about as much screen time as the elliptical prep-and-practice montage. As with that montage, this sequence emphasises work and collaboration. But it distinguishes Tony’s superiority and operates as process.

Rififi draws not merely from the ‘cinema of process’, but hints at mental processes that we are left to infer. We see that something is happening but we are not sure what – the process of problem-solving, of inventiveness, of creativity. Tony does to the alarm what Dassin does to Auric’s score: he mutes it. The result is genius.

The Criminal Bestiary: Of Poodles, Parrots and Fate in The Killing

Stanley Kubrick was notorious for controlling all aspects of his films.

The Killing, Kubrick’s first important film in terms of budget ($320,000), was no different. Distributed by United Artists, which catered to independent producers,

The Killing was based on Lionel White’s novel,

Clean Break, about a racetrack robbery. The ultimate independent producer-director, Kubrick must have been drawn to White’s wonderfully titled novel because it afforded the filmmaker an allegory of modernist aesthetic autonomy – the story of a clean break from the establishment. Yet the fatalism of early heist films, which dismantle the best-laid plans of thieves, is ostensibly at odds with Kubrick’s insistence on complete control over all aspects of his own filmmaking. At the very least

The Killing may be viewed as experimental in the sense that it lays out Kubrick’s intense film ‘modernism’, according to James Naremore, that encompasses among other things ‘a concern for media-specific form, a resistance to censorship, a preference for satire and irony over sentiment, [and] a dislike of conventional narrative realism’ (2007: 3).

Kubrick’s The Killing parroting the noir composition of Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle and Siodmak’s Criss Cross

The Killing’s modernist bent has deep roots in the aesthetic individualism of Romanticism and finds an idiosyncratic expression in the film when Maurice (Kola Kwariani), a chess-obsessed professional wrestler, doles out a life-lesson to the main character, the ex-con Johnny Clay (Sterling Hayden):

You have not learned that in this life you have to be like everyone else. The perfect mediocrity. No better, no worse. Individuality’s a monster, and it must be strangled in its cradle to make our friends feel comforted. You know, I often thought that the gangster and the artist are the same in the eyes of the masses. They are admired and hero-worshipped … but there is always present an underlying wish to see them destroyed at the peak of their glory.

Maurice’s theory of individualism in mass society is intrinsically hostile, facing the mediocrity of conformity against the adulation of the artist-gangster and requiring a metaphorical infanticide. It also presents a self-conscious reading of the gangster genre itself: the masses derive pleasure from the artist-gangster’s catastrophic rise and demise.

The Killing explores the possibility of independence from societal forces coupled with the economic power to break away from the constraints of everyday life on the margins. Johnny has assembled a crew to rob a racetrack of $2 million: Randy Kennan (Ted de Corsia), a corrupt cop looking to pay off debts to a loanshark; Mike O’Reilly (Joe Sawyer), a barman at the track whose sickly wife needs costly medical care; George Peatty (Elisha Cook, Jr.), a track cashier whose adulterous wife, Sherry (Marie Windsor), ridicules his masculinity; and Marvin Unger (Jay C. Flippen), a bookkeeper who bankrolls the operation. Sherry and her younger lover, Val (Vince Edwards), plan to double-cross them. Johnny hires two contract workers to create diversions at the track: Nikki Arcane (Timothy Carey), a sociopathic loner and weapons expert, who will shoot a racehorse; and Johnny’s mentor, Maurice, who will pick a fight with track employees. Johnny points out that ‘none of these men are criminals in the usual sense; they’ve all got jobs, they all live seemingly normal, decent lives. But they got their problems, and they’ve all got a little larceny in them.’ Though not the professional thieves of Huston’s

The Asphalt Jungle, the characters’ willingness to play mercenary shows that their social, economic or psychological marginalisation is enough to draw them into criminal activity.

Echoes of Arthur Fellig (aka Weegee) crime photography in Kubrick’s The Killing

The Killing is about love, obliquely, and violent death, articulated to each other by money and fate, and organised through a comparison between two couples, Johnny and his girlfriend, Fay (Coleen Gray), and George and Sherry. Fate here is not culled from a mythological past. Rather, it comments on the cold abstraction and alienation of mass society, efficiently evoked by the film’s insert shots of crowds at racetracks engaged in a communal gamble. Johnny intends to settle down with Fay. Neither ‘pretty or smart’, Fay dresses soberly in stark contrast to Sherry; phonetically, Fay’s name evokes her faithful devotion to Johnny and their common fate. George and Sherry’s failed relationship stems foremost from Sherry’s cupidity and venality – she’d ‘sell [her] mother for a piece of fudge’, says Johnny. Fickle, sexually alluring, ever the intoxicating femme fatale, Sherry’s emasculating treatment of George pushes him to divulge the plan and then betrays him with her lover, Val.

In the true spirit of the process film,

The Killing’s most important procedural breakdown is that of the crime. It sews together discrete but overlapping events marked rhythmically by repeated stock footage and the racetrack loudspeaker’s voice repeatedly announcing the start of the eventful seventh race.

The Killing’s modernism rejects ‘conventional narrative realism’ (Naremore 2007: 128), portraying itself through the narrator as a ‘jumbled jigsaw puzzle’ and an ‘unfinished fabric’. But it is no postmodernist game of disturbed temporal jostling or perspective in which various points of view compete for truth. The structural effect of the loudspeaker’s repeated phrase is that we read the individual components of the robbery together as a larger whole coordinated in rhythm – and held together by various forms of violence. Maurice’s brute violence against the guards is counterbalanced by the sequence’s symmetrical compositional qualities that give his fight a poetic quality, only to be swept aside by racist, psychopathic violence in the subsequent segment in which Nikki berates a black parking attendant and then shoots the thoroughbred Red Lightning as planned. Another disturbing threat of violence comes in the form of Johnny’s mask and gloves. The clown mask tags Johnny as a mischievous trouble-maker and a monstrous social outcast, and its grotesque mimetic allusion realigns other moments in the film into a singular aesthetic, recasting the pseudo-scientific edge of the film’s dry voice-over against the carnivalesque, the absurd, the surreal. (

The Town and

Batman: The Dark Knight are only the latest heists to exploit the clown mask; another would be the Hughes brothers’

Dead Presidents, which used whiteface to great visual effect.) Within Kubrick’s oeuvre the mask anticipates the frenzied, grotesquely deformed visage of Alex (Malcolm McDowell) as an ‘ignoble savage’ in

A Clockwork Orange (1971) and, less directly, the Venetian masks of

Eyes Wide Shut (1999). The latter harp on the libidinal

eros, whereas

The Killing, by title, evokes

thanatos, death. Johnny’s gun also has a distorted quality. It was the subject of protracted negotiation between Kubrick and the Production Code Administration that had outlawed the use of automatic weapons. Though James B. Harris, Kubrick’s early producer and an important figure early in his career, and Kubrick himself tried to pass a trick shotgun off as an automatic weapon, the PCA disagreed by noting that as long as the audience perceived it as illegal, then the difference was pointless. In the end Kubrick mounted a special handgrip on a shotgun. Because ‘the gun’s odd appearance gives Clay a sinister, deviant menace and adds to the psychological power he wields over the employees’ (Prince 2003: 133), its ‘compromised form’ was well worth the fight with the PCA.

Kubrick’s frightening clown thief

Kubrick’s sardonic contribution to the genre distinguishes it in several respects. If the plot is a ‘fabric’, as the voice-over announces, then Kubrick embroidered a veritable bestiary of horses, dogs and birds into the narrative cloth. Horse racing provides an intertext with

The Asphalt Jungle. In Huston’s film the black mare Dix Handley’s (Sterling Hayden) family had once owned in Kentucky serves a nostalgic function, fixing pre-Depression tranquility in opposition to the city’s post-war decrepitude. In

The Killing, Hayden’s character Johnny asks Nikki to shoot Red Lightning: ‘You’d be killing a horse. That’s not first-degree murder. In fact, it’s not murder at all. In fact, I don’t know what it is.’ If anything, it is an unsentimental affront to his previous character Dix and an oedipally charged homage to Huston. The attention

The Killing gives Red Lightning also makes us question the voice-over’s lucidity. When, in an extreme point of omniscience, the voice-over announces that Red Lightning had only been fed ‘a half-portion of feed’ – quite literally, a tongue-in-cheek moment in the narration – the film pushes the limits of credulity and narratological purpose. Then, Johnny recruits Maurice because he knows he will not ‘squawk if the going gets rough’. This indicts Sherry and George as squawking informants, a fact borne out by the two matching scenes of the couple, hardly lovebirds, at the beginning and end of the film. The film’s first sequence, with the overlapping dialogue and jarring sounds of Sherry and George’s caged bird, foreshadows their last – Kubrick’s explanation of the term

cuckold. Sherry identifies herself as an informant by putting her hand on the cage as the bird squawks in the background – her adulterous ‘squawking’ to Val leads to violent death. When George shoots Sherry and collapses, he takes the birdcage to the floor with him.

The Squawker in The Killing

The last shot of this sequence is a close-up of George’s pockmarked face next to his gun on the floor, with a quick pan to the bird mimicking Sherry’s final words ‘not fair, not fair’. The bird becomes both a figure for the informant couple in opposition to Maurice, but also a mirror figure mocking the exchange between Sherry and George. Finally, Johnny stuffs the stolen money into a suitcase, a ‘Flamingo Hotel’ getaway bag branded with a pink flamingo sticker. Unable to take the suitcase on the plane, Johnny and Fay watch helplessly as a doting old lady lets her poodle, whose curls resemble Sherry’s, run onto the tarmac. A luggage carrier veers to avoid the pooch, the suitcase breaks open as it falls onto the ground, and the cash is released into a swirl of air funnelled by airplane engines. Flamingo Films is the name of the production company Kubrick started with his partner, James Harris, in 1955, and this was their first film. The Flamingo logo never appears in the film. But it takes little effort to read the flamingo suitcase as a playful figure for the producers’ desire to make their own clean getaway. Kubrick himself said that

The Killing ‘was a profitable picture for U[nited] A[rtists] … the only measure of success in financial terms’ (Philips 2001: 144). The narrative outcome constitutes a self-reflexive, poetic act of bad faith to the extent that, unlike what happens in the plot, the film as a product did not fail: it tripled Kubrick’s budget for his next project,

Paths of Glory (1957).

Bob le flambeur

Jean-Pierre Melville’s

Bob le Flambeur is a master

film policier elevated by its ironic unleashing of fate and its self-conscious approach to the genre. Melville claims to have written a serious version of

Bob as early as 1950. But feeling beaten to the punch by

The Asphalt Jungle, Melville abandoned his ‘dramatic or tragic’ screenplay without discarding the theme of the ‘futility of effort: the uphill road to failure’ found there (Nogueira 1971: 53). He rewrote his original screenplay, with assistance from Auguste Le Breton, Dassin’s

Rififi collaborator, turning it into a ‘light-hearted … comedy of manners’ (1971: 53). Melville managed to create in

Bob a dual ‘iconic’ figure that nostalgically resurrected both the American gangster film of the 1940s and the French, pre-war Parisian criminal milieu (Vincendeau 2003: 111). Vincendeau shrewdly proposes that we see in Melville’s mannerist aesthetic a ‘baroque minimalism’ and in his character Bob a self-reflexive cinematic identity, a rather nostalgic one searching to escape the present.

Bob Montagné as iconic gangster in Bob le Flambeur

Melville’s independent streak is legendary, yet his attitude towards collaboration in filmmaking may be misunderstood. Melville acknowledged riding on Le Breton’s success as a writer, but years later he was disappointed with how Le Breton’s underworld slang had ‘aged terribly’ in Bob: ‘Every time I collaborate with someone, something goes wrong. I have to work alone’ (quoted in Nogueira 1971: 55). Melville is not being disingenuous here; he always relied upon the most professional help, such as the editor Monique Bonnot. A more telling case would be his consistent reliance on cinematographer Henri Decaë. Decaë went on to become one of the most important behind-the-camera agitators for New Wave directors like François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol and Louis Malle and mainstream ones like René Clément and Gérard Oury. Nor is Melville overstating his own conception of the director’s lead role for films produced outside of the studio system: ‘I have always had offers to make films which I have always refused’ (quoted in Nogueira 1971: 64). Melville’s commentary on collaboration has more to do with his career-long effort to purify his cinema into a classical elegance than with a disregard for those who supported him. His was a calculating form of independence that found expression on-screen in Bob’s desire for ‘the job of a lifetime’ (‘L’affaire de ma vie’).

The eponymous hero of

Bob le Flambeur, Robert ‘Bob’ Montagné (Roger Duchesne), a modish, silver-haired gambler from Montmartre, spends his nights doing battle with cards and dice. Bob has avoided illegal activity for some time, thanks in part to his friendship with Commissaire Ledru (Guy Decomble), whose life Bob saved during a gun battle. But sensing his age and down on his luck after a loss at the horse track, Bob decides to act on a tip from his friend Roger (André Garet) that the Deauville Casino safe will soon be overflowing with eight million francs. Bob plans to play the casino while his team waits outside for a dawn raid. A croupier at the casino, Jean de Lisieux (Claude Cerval), provides them with the building’s architectural layout and the safe’s specifications, but Jean’s avaricious wife, Suzanne (Colette Fleury), blackmails Bob. Another obstacle arises from Bob’s protection of Anne (Isabel Corey), a young woman on the streets in the seedy world of Pigalle, a neon quarter of Paris at the base of Montmartre, home to nightclubs and cabarets. Anne attracts the attention of Bob’s surrogate son and accomplice, Paolo (Daniel Cauchy), but also that of a brutal pimp, Marc (Gérard Buhr). In pillow talk, to prove his bravado, Paolo boasts of the heist plot to Anne, who accidentally blurts it out to Marc. The police learn of Bob’s plan beforehand, but in a delicious twist of fate, none of the planning will matter. Bob begins to win so well at Deauville on the eve of the robbery that he plays through the night, seemingly impossibly winning against the house, and so distracted by his good fortune, that he completely forgets the job. The team arrives at the casino at the same time as the police, shots are exchanged, and Paolo is fatally wounded. The plan turns out to be a complete failure, yet Bob walks away having taken the house for all of its holdings.

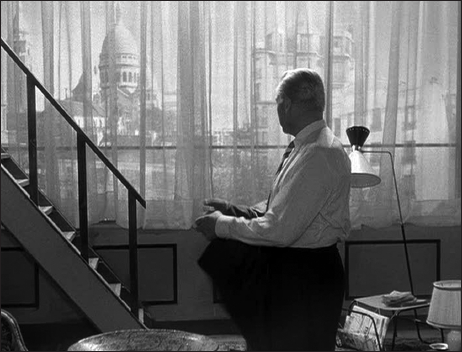

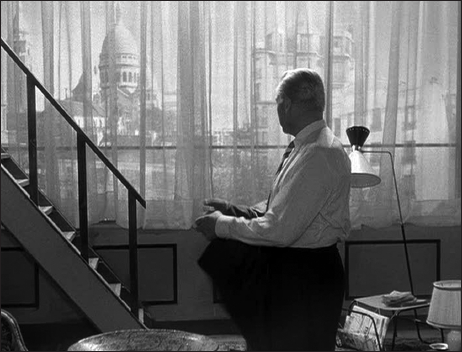

Bob as a modernist artist in Montmartre

The film identifies Bob as an artist and an innovator, a man nostalgic not just for the pre-war order of Paris, but, like the legendary Pigalle he inhabits, for a bohemian nineteenth-century Paris that cradled artists, poets and the

bas-fonds, an underclass of criminals and society’s spurned. Bob’s top-floor painter’s studio that looks through a bay window onto Sacré-Coeur Basilica was a location with special significance for Melville, who had lived in the area as a child. (Asked about the studio at 36 Avenue Junot, Melville answered that Roger Duchesne had actually lived and been arrested there.) When Bob complains about Paolo’s unkempt apartment, Paolo replies: ‘Not everyone can live in a painter’s studio. I’m not an artist [like you]’ (‘

Tout le monde ne peut pas vivre dans un atelier de peintre. Je ne suis pas artiste, moi’). At another moment, Commissaire Ledru mentions the ‘Rimbaud bank’ job that got Bob pinched, likely an allusion to the nineteenth-century poet Arthur Rimbaud, who haunted Montmartre during his brief time in Paris. When we also recognise that Bob is an ageing criminal, one of those ‘weary rogues’ that Truffaut praised; like

Rififi’s Tony le Stéphanois, it is clear that he is more than just an American-French iconic hybrid. His ‘refusal of modernity’ is decidedly modernist, as is his ‘penchant for

actes gratuits’ (Vincendeau 2003: 211). He is a hold-out from the past who recuperates several threads of the modernist tradition. Ultimately, the construction of Bob as an artist-idea-man from Montmartre places him in a constellation of figures of Parisian modernity that includes the painter, the poet, the gambler and the dandy (through his sartorial meticulousness), each a forebear to and proxy for the gentleman gangster in the fictional twentieth-century criminal world of Melville’s making.

The planning and heist sequences bear the marks of Melville’s attention to process, enhanced with a rich metaphorical layering akin to the representational strategies of Dassin’s

Rififi. The planning sequences entail work; the ‘

coup’, or job, is all about play. The voice-over says simply that the planning and setup constitute a ‘waltz’ (literalised at several moments by the score composed by Eddie Barclay and Jo Boyer). The planning montage in

Rififi evoked a concert through the relation of sound and image, and the robbery was performed as if it were a choreographed dance of manual labour. The self-conscious narrator of

The Killing, on the other hand, called his story a ‘fabric’ and a ‘jigsaw puzzle’. In

Bob, Melville’s self-conscious metaphorical recourse for planning and prep is, like

Rififi, to music and dance, which convey geometry and graceful movement in time. Colin McArthur links Melville’s cinema to the materialist philosophy of the French

nouveau roman, whose interest in the ‘brute facticity of objects in the real world’ inspired the filmmaker’s ‘cinema of process’ (2000: 191). The canonical texts for this ‘virtually wordless attention to physical actions’ (McArthur 2000: 192), post-date

Bob (

Le Doulos [1962],

Le Deuxième souffle [1966],

Le Samouraï [1967]), yet this aspect of Melville’s cinema can be found in

Bob (see M. Smith 1995: 218–23).

The planning sequences complicate a simplistic view of Melville as a filmmaker solely of materialist process. As Bob trains his platoon of ‘parachutist commandos’ – this military terminology stems not only from the war’s effect on film noir, but specifically Melville’s fascination with the French Resistance – he places the men in position in a vacant lot on which he has traced to scale the layout of the casino, as if they were actors working through their parts in a play that Bob was directing. And, in fact, following this practice run, Melville inserts a dreamlike sequence (one and a half minutes long) in which Bob imagines the heist unfolding according to his plan. Cued by the narrator, we experience the imaginary event as focalised by Bob. Everyone is in place, but the eeriness of the deserted space is only heightened by a melody of strings, muted wind instruments and xylophone. Strictly speaking, this is not a prolepsis foreshadowing what will happen, but it does set up expectations of what will follow. (Lenny Borgher’s ingenious English subtitles for the Criterion Collection DVD interpret the sequence in just such a way by rendering Melville’s spoken French narration ‘Voilà comment, d’après Bob, tout doit se passer’ [‘Here’s how, according to Bob, everything must happen’] as ‘Here’s how Bob pictured the heist’; emphasis added.) On the other hand, as an example of Melville’s visual eclecticism, the subsequent sequence showing Roger refining his use of technology to break the safe eschews the recourse to long takes and ambient sounds in favour of a more dramatic rhythmic editing. In this sequence Bob, Paolo and the fence McKimmie – and McKimmie’s German Shepherd – look on and listen attentively as Roger augments the sound of his work on the safe’s tumblers by means of a speaker and oscilloscope. The sequence cycles through a series of close-ups of each of the men watching Roger, interspersed with shots of the devices and the dog panting with his ears perking up, building towards a climax. The narrative point of the sequence is to show Roger perfecting his timing through technological enhancements, but its aesthetic consequence is to demonstrate Melville’s own stylistic variability.

Melville’s approach to gambling and chance have far-reaching ramifications for the noir heist film as a narrative of fate and failure, and for narrative dynamics generally. In reworking Huston’s plot, Melville places the robbery at the very end of the narrative; it never materialises as planned, becoming instead ‘an ironic non-event which in fact never takes place’ (Kavanagh 1993: 144). This too is part of what the narrator introduces as the ‘curious’ story of Bob. It plays off the expectation and build-up to a climactic event, only to veer in another direction, a let-down that still manages to fulfill its promise of process – but through gambling sequences that occupy the final fifteen minutes of the film and not the planned robbery. Bob had promised Roger not to gamble until after the job, but when de Lisieux fails appear to give access to the safe, Bob decides to wait for the job by doing just that. At first he plays casually, but is slowly drawn into the games: roulette at first, then the French card game

chemin de fer. He wins so well that he departs for the higher stakes of the private rooms. While there is ellipsis in these sequences (Bob starts at 1:30 a.m. and moves to the private rooms at 2:45) and a tightly edited montage of play, Melville also extends the process of playing and winning in much the same way he had done for the planning and practice sequences. Bob’s ‘old mistress’ Luck returns, he forgets why he is there, and in a completely unforeseeable turn of events, his winning streak continues, unabated, until he entirely breaks the house. (See Kavanagh’s intricate explanation of the games Bob plays and the mathematical improbability of his wins; 1993: 154–6.) When he finally looks at his watch, it is already 5 a.m., the moment his gang is to carry out the ‘raid’. The police, tipped off by the scheming Suzanne, arrive at the same moment, a gunfight ensues, and Paolo is mortally wounded.

The title establishes Bob as a risk-taker whose mode of existence is based on chance.

Flambeur is a French slang term that entered common usage in the nineteenth-century. It connotes a person devoted to high-stakes casino gambling and stems from a figurative use of the verb

flamber, which, properly speaking, means to burn quickly and violently. Here, it touches on the sense of a mad, rapid expenditure of one’s fortune, as if consumed by flames. This connotation takes our reading in the direction of Thomas Kavanagh’s absorbing analysis of

Bob le Flambeur, which opens onto the theoretical assumptions surrounding chance and gaming; Kavanagh shows that Melville’s self-conscious work meditates on ‘the ironies to which we expose ourselves in claiming to be [chance’s] masters, and on its corrosive relation to all narratives of human planning and control’ (1993: 145). Melville makes explicit the underlying irrationality of human endeavours that rely entirely on rational control, a lesson the noir heist borrowed from film noir and refined for its own purposes. Moreover, Kavanagh underlines our surprise at Bob’s ‘faith … in the technical skill of the master

casseur [robber] rather than in the luck of the consummate

flambeur’ that had defined his life to that point: ‘Bob defines his future not as an exploitation of chance, but as the execution of the carefully planned narrative’ (1993: 148). The exquisite yet biting irony for Bob is that in winning so magnificently, he has utterly destroyed his rational plan and undermined the good faith of his collaborators. Melville’s mannerism ensconces the genre in a meditation on (narrative) aesthetics and money, idolising the risk-taking criminal as a stand-in for the filmmaker, who must navigate an entrenched post-war consumer society with which he was at odds.

Comedy Breaks into the Genre: The Lavender Hill Mob and Big Deal on Madonna Street

Among Kim Newman’s insights into the ‘caper’ film is that it individuated as a heist sub-genre when it ‘evolved’ from its ‘embryonic form’ as a gangster film in double fashion, from ‘serious’ to ‘glamorous’ films, and from dramatic capers towards ‘such glossy, stylish fantasies such as

Ocean’s Eleven, which with its self-mocking stars and flip punchline might be considered the first real caper movie’ (1997: 71). Underscoring the ‘victory of style over morality’ in romantic caper comedies from 1960 onwards, Newman’s concise history blends the phases of the heist film with typological aspects that rightly segregates the ‘caper’ from gangster films and films noirs. The glamorous caper was preceded by foundational comic heist films from the 1950s that overlapped with the foundational noir heists already mentioned, most notably the groundbreaking 1951 Ealing Studios productions,

The Lavender Hill Mob, and Mario Monicelli’s 1958 Italian-language satire,

Big Deal on Madonna Street. The significance of these films lies in their reliance on the familiarity with dramatic works worthy of parody. In one sense, these films borrowed against the dramatic force of the noir heist while channelling similar semantics and syntax for comic ends. The distinction in mode between tragic and comic plots is thus a historical and structural feature of the genre that exists from the outset.

Ealing Studios Capers

Charles Crichton’s The Lavender Hill Mob is an original film, by all accounts the first fully emerged heist from Great Britain, which laid the groundwork for Alexander Mackendrick’s 1955 comedy The Ladykillers. The Ladykillers came out as the round of gritty American and French crime thrillers examined above were solidifying the noir heist. In retrospect, the two films are clearly at the forefront of the emerging heist genre, though they were not necessarily recognised as such by their directors and producers, who approached the heist in a unique way long before comedy became a mainstay in the years following 1960. But this elides the fact that they were also among the most visible titles in the Ealing Studios’ ‘eccentric’ comedies of post-war Britain. This is no laughing matter, since Ealing comedies, despite their relatively small number, may be taken as a metonym for ‘British cinema’ of this era because of their far-reaching and enduring influence, ‘project[ing] a view of British character’ founded in respectability and coupled with a ‘mild anarchy’ (Pulleine 2001: 81) that sat well with the social message of the heist.

The cultural projection of ‘Englishness’ was the conscious agenda of Ealing’s studio head, Sir Michael Balcon. The Ealing films of the late 1940s and early 1950s were not so much genre-oriented as thematically aligned around ‘the social process that ratified notions of right and wrong’ (Harper and Porter 2003: 60). Several of the Ealing films thus relied on criminal activity for their humour and moral message, though Balcon felt there was little moral ambiguity in his narratives: children thwarting a robbery in

Hue and Cry (Charles Crichton, 1947), outrageous multiple murders in

Kind Hearts and Coronets (Robert Hamer, 1949), a major theft by villagers in

The Titfield Thunderbolt (Charles Crichton, 1953) and murder and robbery in

The Ladykillers. Balcon’s influence over subject matter went hand in hand with an exaggerated sense of the familial culture of his artistic teams over whom he wielded enormous power. So much power, it appears, that Balcon’s inflexibility may have contributed to the eventual disintegration of Ealing in the late 1950s. He misperceived the changing social tides in Great Britain, a major flaw in itself, but more germane for our purposes is the fact that he doggedly refused greater freedom to his creative teams and argued for the artistic quality of film in the face of Hollywood’s consumerist attitudes while he increasingly treated film as an industrial product (Harper and Porter 2003: 58).

Among Ealing’s most profitable films were The Lavender Hill Mob and The Ladykillers, which enjoyed critical and box-office success at home and abroad (Harper and Porter 2003: 284, n2). Balcon felt their good-humoured fun did not threaten police authority, and critics have agreed that they ‘allow no space for meditation’ over right and wrong, bringing their thieves ‘round to knowing guilt and experiencing justice’ by narrative end (Harper and Porter 2003: 61) and ‘reducing the action to a game in which the powers-that-be have an inbuilt right to win’ (Pulleine 2001: 82). Comedies of manners tend to be conservative in their reestablishment of the social order at the end. Nevertheless, this position betrays the very ludic qualities that define these comedies, which may yet express aspirations for artistic autonomy and creative control in a way that Balcon seems never to have surmised. Balcon may have had the first laugh, so to speak, in ‘limit[ing] the directors’ freedom of choice and interpretation’, given that ‘conditions at Ealing were extremely unconducive to the development of a personal “signature”’ (Harper and Porter 2003: 62, 63). But the resonances these two Ealing comedies share with the noir heists of Dassin, Kubrick and Melville, in allegorising creative processes through crime, tell us they also encode artistic aspirations for film as an art of collaboration in commercial society. All of these films end in disastrous failure, but the Ealing works end in a failure that is disastrously hilarious. Whatever the modal differences between the dramatic and the comic, The Lavender Hill Mob begs to be read in conjunction with its noir counterparts.

The heist film frequently distinguishes between fine art and commercial or mercantile objects as a metaphor for its own place in a consumer society that transforms the value of mass art. That the heist film is aware of the apparently mutually exclusive relation between art and commercial products becomes strikingly clear in an extraordinary exchange of letters between British film representatives and officials of the 1951 Venice Film Festival over the fate of the

The Lavender Hill Mob. In the months leading up to the festival, Balcon and festival director Antonio Petrucci engaged in a flurried disagreement over the film’s place in the festival as one of four official British entries. (The correspondents included Petrucci; Balcon; John Davis of Ealing’s distributor, the J. Arthur Rank Ltd. Organisation; and Henry French, chairman of the British Film Producers Association Festivals committee.) When the Ealing production got off to a promising box-office start, Petrucci called it a ‘commercial rather than a festival film’ and predicted that it would not win a prize (June 29, 1951, letter sent to Davis). A clearly irritated Balcon dismissed Petrucci’s assessment:

From Ealing’s point of view, we would not care whether the film won a prize or not; we would not even care if it were hissed off the screen; because although there are no absolute values as far as an art form is concerned … we know enough to realise that all that matters on these occasions is that the small proportion of a film festival audience that is not parasitical, should see the best that this country has to offer. (July 2, 1951, to French)

French in turn wrote to Petrucci that it should not be the festival’s purpose to ‘draw … or encourage the wholly artificial distinction between commercial and festival films’ (July 4, to Petrucci). Petrucci’s riposte was that ‘commercial success does not often mean that a film is artistically superior’ (July 7, to French). Balcon was to get the last laugh in the matter; the jury awarded the prize for best screenplay to screenwriter T. E. B. Clarke. The sense that life imitates art here is a point Balcon and Petrucci apparently overlooked in their assessment of the film’s reception. The point is far too valuable to ignore because the film itself poses this very dichotomy between art and commerce, between an imaginative and a thick-headed quantitative mentality, even as it exploits the difference for purposes equally commercial and aesthetic.

The Lavender Hill Mob was indicative of a momentary turn in early 1950s British crime films away from the overt violence and underworld milieu of spiv-gangster movies (McFarlane 2001: 276; see also Robertson 1999). Despite the film’s moralising or ‘parochial’ conclusion, in which Scotland Yard captures the culprits, it still manages to privilege a crucial commitment to failure – a strategic commitment beyond studio censorship that gives the film community with the post-war noir heist. Most heists of the 1950s were dramatic and predominantly fatalistic; the comic heist’s less elevated style and gentle mockery of its characters, though not fatalistic (let alone cynical), still ends in catastrophic failure.

The Lavender Hill Mob is built around the exceptional writing of T. E. B. Clarke and acting of Alec Guinness. Clarke’s screenplays (he also wrote Hue and Cry and The Titfield Thunderbolt) elevate oft-ignored small-society and working-class types, a fruitful tie to the social outcasts who populate the heist film, and sustain a gentle suspicion of commercialism that surely applies to the plot of The Lavender Hill Mob (Dacre 2001: 236). Alec Guinness plays the unassuming banker Henry Holland, who for twenty years has dutifully escorted gold bullion from the refinery to the bank, quietly biding his time for the right moment to hatch his plan. He eventually forms a ‘mob’ to steal gold bullion, recast it as Eiffel Tower souvenirs, and export them to France, where he and his partner will recoup the gold shipment and live in financial prosperity. Of course, everything goes awry in Paris, and the partners are forced to return to England to recover a handful of gold towers that accidentally get away. The flashback structure of the narrative accentuates the sense of Holland’s failure. The film begins in South America, where Holland has been living it up for a year in the lap of luxury. He recounts in voice-over how he had been ‘merely a non-entity among those thousands who flock every morning into the city’ – an evocation of modern mass society, which exploits the nameless and faceless for the benefit of a few – as the frame dissolves to a shot of a London bridge where teeming hordes of workers cross on foot. Holland’s narration shifts us back in time to when he was working in London, where in his staid, dark wool suit and bowler hat – a man of ‘no imagination, no initiative’ say his superiors – he observes refinery workers pouring molten gold into bar molds.

The film valorises invention and creative ingenuity, in the context of a distinction between fine art and commercial objects. If Holland is to somehow steal the gold bars, he needs both an accomplice and a means for getting the gold out of the country. This comes in the form of Alfred Pendlebury, a new pensioner in Holland’s building in the unassuming, unexciting quarter of Lavender Hill. When Pendlebury moves in, he brings with him busts and other art objects, much to the chagrin of the proprietor, Miss Evesham (Edie Martin), who mistakes his objects for merchandise. She tells him he cannot conduct his ‘business occupation’ there, but he proclaims: ‘Ah, my dear lady, this is not my business occupation. No! These are my wings … My business occupation is something unspeakably hideous.’ Pendlebury sells souvenirs to British tourists at home and abroad, ‘propogat[ing] British cultural depravity’ to the masses of consumers who unknowingly buy abroad what is made within miles of their own homes. During a visit to the factory’s casting, Holland discovers the Eiffel Tower paperweights Pendlebury exports to France. A tower on a pedestal music box plays the can-can above the din of machinery as the camera pans to the casting vat, where two workers pour molten lead into a mold; when a fleck falls on Holland’s shoe, he instinctively flicks it back into the mould and is reminded of the gold refinery. In this shot, the camera pans up to Holland’s transfixed face. Holland transforms into Vulcan, an inventor-genius with a creative, rather than quantitative, mind. (The sequence anticipates the trial-and-error mental process by which Tony Le Stéphanois comes to realise he can use an ordinary fire extinguisher to mute the sound of a jewellery store alarm in

Rififi.) The frame then dissolves to Holland looking intently off-screen at Pendlebury, who is busy sculpting a bust and mumbling to himself: ‘I shall call him “The Slave”.’ The sequence reiterates the heist’s restlessness with modernity and the latter’s occupational ennui and enslavement, including its outrageous commodification of culture.

The Lavender Hill Mob’s finale links it to the modernist aspirations we examined previously, extending the backdrop of modernity so frequently associated with Paris as a primary locus of the modernist avant-garde into mainstream film. Holland and Pendlebury successfully export their contraband to Paris, where they have planned to recover the precious souvenirs from Pendlebury’s vendor on the Eiffel Tower. She has unwittingly sold them to a group of British schoolgirls.

Pendlebury to his female vendor: I told you never to use a crate marked ‘R’!

The woman, with a heavy French accent: But that is not an ‘ahr’, Monsieur. It is an ‘err’ [eh-rr]!

Pendlebury, discombobulated: It’s an ‘r’ [‘are’] in English!

As the irony of Pendlebury’s comment about cultural depravity now becomes clear, the two bumbling thieves take off to track down the objects for fear that, once in England, the objects could be traced back to them. The girls having taken an elevator, Holland and Pendlebury hurry down a winding service staircase. The standout two-minute sequence of their vertiginous descent is marked by rapid cross-cutting between Holland, Pendlebury and the elevator, intercut with shots from the interior of the Tower towards Paris in the background. The men circle the staircase in an overheard shot made by the camera spinning wildly on its axis, until the image itself spins out of control onto the ground. As they spin, a wide angle lens distorts their shapes and the Tower in the background, its iconic frame teetering back and forth in vertigo.

The verbal wit and formally self-conscious visuals of this sequence recall several avant-garde moments, whether Crichton intended this or not. They include 1920s New Photography (part of Robert Siodmak’s background and visual style in

Criss Cross and

The Killers), Dadaism and other modernist film experiments. Dada may be behind the verbal play of the sequence, since Marcel Duchamp’s infamous readymade urinal

Fountain (1917), signed ‘R. Mutt’, and one of his pseudonyms, Rrose Sélavy, a pun on

Eros, c’est la vie (‘Eros is life’), which featured in his short

Anemic Cinema (1926), both play with the French ‘er’, the very phoneme that produces the catastrophic error in

The Lavender Hill Mob. The City Symphony films, fascinated and repulsed by the rapid technological change, uncanny spaces and demographic concentration of the modern metropolis, were ‘poetic records of the camera’s ability to capture the dynamic rhythm and kaleidoscopic pattern of city life’ (Barsam 1992: 59). Another possible precursor would be René Clair’s Dadaist experiment

Entr’acte (1924) or his fantastical

Paris qui dort (1925). The final segments of

Entr’acte involve a funeral procession that (quite literally) turns into an unhinged roller-coaster ride through the city of Paris, thanks to rapid editing and swirling camera effects. The science-fiction comedy

Paris qui dort portrays a small group of people saved from a mad scientist’s device that instantaneously immobilises everyone else in the city. They walk through the streets, briefly experiencing a life of ease and hedonistic pleasure, thieving where necessary from the inhabitants frozen in time. They bring their booty to the top of the Eiffel Tower where they take in the full view of the city. This reminds us of Clair’s conversion of the Eiffel Tower into a cinematic apparatus, a ‘viewfinder’ and veritable tripod for unique tilts and crane shots: ‘The [T]ower, then, is not only a complex, infinitely stimulating set; it provides a range of low- and high-angle positions, a vocabulary of movement, a play of light and shadow, of solid and void, which generate visual tension, a range of kinetic responses’ (Michelson 1979: 39). Likewise, in

The Lavender Hill Mob the Eiffel Tower becomes a cinematic playground and apparatus for unusual visual effects for the DP Douglas Slocombe, production designer William Kellner, editor Seth Holcome and special effects supervisor Sidney Pearson, all Ealing regulars. (The film’s score was written by Georges Auric, the prolific composer who slipped easily between the Paris Opera and film, including

Rififi.) Whatever its flaws (Harper and Porter call the traveling mattes in back-projection ‘ham-fisted’; 2003: 203), Crichton’s team appeared to absorb visual practices of urban modernity into the sequence, introducing them in a controlled way into a mainstream film. Thus,

The Lavender Hill Mob’s disarming comic effects belie a sophisticated visual strategy that places it squarely alongside the modernist affirmations of the noir heist. Unlike the utopian hopes in the ‘new man’ manifest in interwar avant-garde film and photography, however, this post-war sequence undoes the ‘new man’s’ invincibility through comic as opposed to tragic failure.

Spurred by The Lavender Hill Mob’s success, Ealing would strike again with its darkly comic heist The Ladykillers. Despite showcasing Guinness and newcomer Peter Sellers, the film may have suffered from its ‘caricatural’ depiction of old and new Britain (Pulleine 2001: 83) or its ‘cartoonish’ set design (Harper and Porter 2003: 203). What is more certain is that it succumbed to the very tensions between studio and director behind so many 1950s heists, if not the genre in general. Balcon insisted director Alexander Mackendrick cut his first version by a full eight minutes. Besides dropping extensive parts with Guinness, Mackendrick was forced to splice the robbery sequence, whittling down the crucial process at the heart of the heist. Nevertheless, viewing this set of Ealing comedies from the standpoint of the heist genre reminds us that their success rests in part on breaking new ground in terms of genre.

To close out this chapter, I will briefly pause on one final film, Mario Monicelli’s

I soliti ignoti (

Persons Unknown in the UK,

Big Deal on Madonna Street in the US). Monicelli’s film is a milestone comic heist for its tenderhearted, yet highly intelligent parody of the fatalism and the methodical, quasi ‘scientific’ efforts of the noir heist. Already in 1951

The Lavender Hill Mob had shown the distance the genre could take from the seriousness of Siodmak’s or Huston’s noir heists, but it still relied upon the creative intelligence of its planners and the perfect execution of the robbery and smuggling plan. The satire in

I soliti ignoti goes one step further in self-consciously undermining and overplaying heist semantics for comic ends: the bungling thieves never even get close to the cash hidden in a pawnshop safe. Furthermore, just as the powerful metonymic qualities of

The Lavender Hill Mob made it emblematic of ‘Ealing’ comedy and ‘British’ film,

I soliti ignoti is a ‘foundational film’ in the successful run of late 1950s and early 1960s Italian comic works grouped together as the

commedia all’italiana (Celli and Cottino-Jones 2006: 88; see also Bondanella 2009: 180–1 and Brunetta 2009: 164).

As parody,

I soliti ignoti’s specific intertext was Dassin’s

Rififi, but it also seamlessly incorporated elements from Italian theatre and film. In Italianising elements of a French-American crime film, Monicelli broadened the borders of the genre without bending the rules too far from topical cultural concerns surrounding work and economic opportunity. The story takes place in Rome, emphasising the Roman dialect (Brunetta 2009: 181), though regional accents and stereotypes appear along the way. The crew resemble typical heist characters, yet they clearly draw on ‘ancient character types from the theatrical tradition of the

commedia dell’arte’ (Celli and Cottino-Jones 2006: 88; see also Bondanella 2009: 180). The crew’s hard-knock leader, the boxer Peppe (Vittorio Gassman), represents a kind of

miles gloriosis captain. Peppe turns to a rag-tag crew for the job: an out-of-work photographer named Tiberio (Marcello Mastroianni); the fiery Sicilian Michele Ferribotte (Tiberio Murgia), a

zanni clown figure representative of Sicily; the young apprentice Mario Angeletti (Renato Salvatori), who crosses Michele when he falls for Michele’s kept sister Carmelina (Claudia Cardinale); and the elderly lookout Capannelle (Carlo Pisacane), whose technical utility never seems worthy of the task because he too is a clown, the Harlequin-like ‘dispossessed worker from Bergamo’ (Celli and Cottino-Jones 2006: 88). The crew receive instruction from a professional safecracker, Dante Cruciani (played by the inimitable Totò), who is a Neopolitan-style

zanni; as a black-market capitalist, he makes a respectable living by renting tools to thieves. To get to the pawnshop’s safe, the crew must break through the wall of an adjacent apartment owned by two spinsters, so Peppe sets about seducing their flirtatious Venetian maid, Nicoletta (Carla Gravina). Despite the crew’s repeated attempts to approach the job ‘scientifically’, a phrase Peppe repeats at key moments during the planning and robbery sequences, the crew fails to meet his high expectations. They do break through a wall in the spinsters’ apartment – in a clear reference to

Rififi, Peppe is sweating profusely from the hard drilling – but they only manage to pierce through the kitchen wall. Capannelle sets a table of leftover

pasta e fagioli, and the crew expends its final hours eating and bickering about the job instead of pulling it off. As they split up, Peppe and Capannelle hide from two beat cops in a crowd of men waiting for work calls; the crowd drags them along behind a worksite fence against their will – Peppe and Capannelle represent a will

not to work. The massive worksite fence resembles a prison. Capannelle escapes and calls to Peppe, ‘They’ll make you work!’ but Peppe accepts his lot. Celli and Cottino-Jones describe ‘the return to stock characters in the cinema [as] a comfort, even a reassurance of cultural identity in the impending consumerism, migration, and continuing industrialization of the Italian economy’ (2006: 90).

Among the self-conscious charms of Big Deal on Madonna Street is its parody of filmmaking itself. Tiberio, the photographer, is assigned the task of filming the pawn shop to lift the safe’s combination. Monicelli’s comic genius is to build this self-reflexivity around a character type devoid of ‘self-awareness’. The crew assemble to watch the film together, as if they were in a theatre, but the experience is a disaster. Tiberio’s film is out of focus, the frame is jumpy, and there is no logic to the editing (shots of the safe are intercut with ones of his own baby). His disclaimer? ‘It’s not Hollywood!’ At the crucial moment, when Tiberio is supposed to film the safe’s combination, a clothesline drags in front of the camera, blocking the view. Dante declares: ‘As a film, it’s a failure.’ Monicelli must have taken great pleasure in consciously keeping his distance from Hollywood, even as he has the young apprentice Mario, his namesake in the film, break off from the gang for a job taking tickets at the local movie theatre.

Parody’s parasitic nature recognises, instrinsically, the conventional formula against which it makes its statement. But parody does have a shelf-life: the otherwise successful Nanni Loy directed a slack sequel to

I soliti ignoti two years later,

Audace colpo dei soliti ignoti – ‘The Audacious Crime of the Usual Suspects’, which reunited several characters to rob the cash receipts of a Milan football match. Monicelli’s films, possible only as a ‘reversal of the generic expectations of the caper film’ (Bondanella 2009: 181), intimated that the noir heist was a fully realised criminal sub-genre in need of tweaking, renewal, or a new social function. Before the glamorous Hollywood capers of the 1960s made their mark, Monicelli found his way to a satirical model by embedding ‘a cynical sense of humor reflecting the human drive for survival in the face of overwhelming obstacles’ (ibid.), much in the spirit of the noir heist. Monicelli shows that heist comedy can be every bit as forceful a weapon as the fatalism of the noir heist for commenting on real social and economic problems, without losing sight of its utility for reflecting on film as art. The best practitioners of the heist as a vernacular modernist enterprise find moments to acknowledge its precariousness. At least this was the case in the foundational noir heist films, and here we see it in the finest early comic heists as well.