CHAPTER ELEVEN

ACADEMIC ANTISCIENCE

Stupidity is the twin sister of reason: It grows most luxuriously not on the soil of virgin ignorance, but on soil cultivated by the sweat of doctors and professors.

—WITOLD GOMBROWICZ, 1988

Science and ideology are incompatible.

—JOHN S. RIGDEN AND ROGER H. STUEWER, 2004

Once the liberal democracies had prevailed against fascism and communism—vanquishing, with the considerable help of their scientific and technological prowess, the two most dangerously illiberal forces to have arisen in modern times—you might think that academics would have investigated the relationship between science and liberalism. The subject had come up before. In 1918 the president of Stanford University suggested that “the spirit of democracy favors the advance of science.” In 1938 the medical historian Henry E. Sigerist allowed that while it might be “impossible to establish a simple causal relationship between democracy and science and to state that democratic society alone can furnish the soil suited for the development of science,” it could hardly “be a mere coincidence…that science actually has flourished in democratic periods.” In 1946, the historian of science Joseph Needham argued that “there is a distinct connection between interest in the natural sciences and the democratic attitude,” such that democracy could “in a sense be termed that practice of which science is the theory.” Inquiring into why this might be so, the Columbia University sociologist Robert K. Merton considered, as a “provisional assumption,” that scientific creativity benefits from the increased number of personal choices found in liberal-democratic nations. “Science,” he wrote, “is afforded opportunity for development in a democratic order which is integrated with the ethos of science.” In 1952, Talcott Parsons of Harvard argued that “only in certain types of society can science flourish, and conversely without a continuous and healthy development and application of science such a society cannot function properly.” As befits scholarly inquiry, the tenor of these investigations was modest, the researchers cautioning that the subject was complex and their findings preliminary. Bernard Barber, a specialist in the ethics of science, portrayed the relationship this way:

Examination will show that certain “liberal” societies—the United States and Great Britain, for example—are more favorable in certain respects to science than are certain “authoritarian” societies—Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. We say that the latter countries are “less favorable” we do not say that science is “impossible” for them. This is not a matter of black-and-white absolutes but only of degrees of favorableness among different related societies.

A good start, you might think; something to build on. But instead, academic discourse took a radical turn from which it has not yet fully recovered. Rather than investigate how science interacts with liberal and illiberal political systems, radical academics began challenging science itself, claiming that it was just “one among many truth games” and could not obtain objective knowledge because there was no objective reality, just a welter of cultural, ethnic, or gendered ways of experiencing reality. From this perspective what are called facts are but intellectual constructions, and to suggest that science and liberalism benefit each other is to indulge in “the naive and self-serving, or alternatively arrogant and conceited, belief that science flourishes best, or even can only really flourish, in a Western-style liberal democracy.”

These recondite theories went by a variety of names—deconstructionism, multiculturalism, science studies, cultural studies, etc.—for which this book employs the umbrella term postmodernism. They became so popular that generations of educators came to believe, and continue to teach their students today, that science is culturally conditioned and politically suspect—the oppressive tool of white Western males, in one formulation. Teachers—some of them—loved postmodernism because, having dismissed the likes of Newton and Darwin as propagandists with feet of clay, they no longer had to feel inferior to them but became their ruthless judges. Students—many of them—loved postmodernism because it freed them from the burden of actually having to learn any science. It sufficed to declare a politically acceptable thesis—say, that a given thinker was “logocentric” (a fascist epithet aimed at those who employ logic)—then lard the paper with knowing references to Marx, Martin Heidegger, Jacques Derrida, and other heroes of the French left. The process was so easy that computers could do it, and did: Online “postmodernism generators” cranked out such papers on order, complete with footnotes.

It seemed harmless enough at first. The postmodernists were viewed as standing up for women and minorities, and if they wanted the rest of us to prune our language a bit to make it politically correct, that seemed fair enough at a time when many white males were still calling women “girls” and black men “boys.” Not until postmodernists began gaining control of university humanities departments and denying tenure to dissenting colleagues did the wider academic community inquire into what the movement was and where it had come from. What they found were roots in the same totalitarian impulses against which the liberal democracies had so recently contended.

An early sally in the postmodernist campaign came in 1931, when a communist physicist named Boris Hessen prepared a paper for the Second International Congress of the History of Science, in London, interpreting Newton’s Principia as a response to the class struggles and capitalistic economic imperatives of seventeenth-century England. In it, Hessen deployed three tools that became indispensable to his radical heirs. First, the “great man” under consideration—in this case Newton—is reduced to an exemplification of the cultural and political currents in which he lived and on which he is depicted as bobbing along like a wood chip on a tide: “Newton was a child of his class.” Second, any facts the great man may have discovered are declared to be not facts at all but “useful fictions” that gained status because they promoted the interests of a prevailing social class: “The ideas of the ruling class…are the ruling ideas, and the ruling class distinguishes its ideas by putting them forward as eternal truths.” Finally, the great man’s lamentable errors and hypocrisies, and those of the society to which he belonged, are brought to light through the application of Marxist-Leninist or some other form of illiberal analysis aimed at reclaiming science for “the people”: “Only in socialist society will science become the genuine possession of all mankind.”

Ordinarily a clear writer, Hessen couched his London paper in obfuscatory jargon, declaring it his central thesis to demonstrate “the complete coincidence of the physical thematic of the period which arose out of the needs of economics and technique with the main contents of the Principia.” Put into plain English, this says that the economic and technological currents of Newton’s day completely dictated the contents of the Principia—that the noblemen and tradesmen of sixteenth-century England got what they wanted, which for some reason was a mathematically precise statement of the law of gravitation, written in Latin. Hence the need for obscurantist rhetoric: Had Hessen’s thesis been clearly stated, it would have read like a joke.

Which, in grim reality, it appears to have been. Loren R. Graham, a historian of science at MIT and Harvard who has written widely on Soviet science, looked into the Hessen case in the nineteen eighties. He was puzzled by the fact that this dedicated communist, whose London paper was a model of Marxist analysis, was soon thereafter arrested, dying in a Soviet prison not long after his fortieth birthday. Why, Graham wondered, had this happened?

What he found was disturbing. Hessen’s communist credentials were indeed impressive. He had been a soldier in the Red Army, an instructor of Red Army troops, and a student at the Institute of Red Professors in Moscow. His scientific credentials were equally solid. A gifted mathematician, he studied physics at the University of Edinburgh and then at Petro-grad before becoming a professor of physics at Moscow University. And yet, Graham found, by the time Hessen “went to London in the summer of 1931 he was in deep political trouble.”

The cause of the trouble was science. As a physicist, Hessen taught quantum mechanics and relativity, but neither of these hot new disciplines comported with Marxist ideology. Marxism is strictly deterministic—full of “iron laws” of this and that—whereas quantum mechanics incorporates the uncertainty principle and makes predictions based on statistical probabilities. Relativity is deterministic but was the work of Einstein, who came from a bourgeois background and, even worse, had taken to writing popular essays about religion that showed him to be something of a deist rather than a politically correct atheist. Had Hessen been a cynic he might have faked his way through the conflict, but being an honest communist he stood his ground. He implored his comrades to criticize the social context of relativity and quantum mechanics if they liked, and to reject the personal philosophies of Einstein and other scientists as they saw fit, but not to banish their science—because the validity of a scientific theory has little or nothing to do with the social or psychological circumstances from which it arises. In a way his position resembled that of Galileo, a believing Christian who sought to save his church from hitching its wagon to an obsolete cosmology. As a faithful Marxist, Hessen tried to dissuade the party from continuing to oppose relativity and quantum mechanics, since to do so would blind students to the brightest lights in modern physics.

For his trouble, Hessen was denounced by Soviet authorities as a “right deviationist,” meaning a member of the bourgeoisie who fails to identify with the proletariat (his father was a banker), and as an “idealist” who had strayed from Marxist-Leninist determinism—which Marx and Lenin had learned from popular books about nineteenth-century science and then enshrined in the killing jar of their ideology. To keep an eye on him, the party had Hessen chaperoned in London by a Stalinist operative, Arnost Kooman, who just three months earlier had published an article declaring that

Comrade Hessen is making some progress, although with great difficulty, toward correcting the enormous errors which he, together with other members of our scientific leadership, have committed. Nonetheless, he still has not been able to pose the issue in the correct fashion, in line with the Party’s policy.

Hessen evidently hoped that his London paper would awaken the party to its folly by demonstrating that a social-constructivist analysis could be made even of Newton. Marxists accepted the validity of Newtonian physics, even though Newton lived in a capitalist England. So, therefore, should relativity and quantum mechanics be acceptable, regardless of their alleged political infelicities. Writes Graham:

The overwhelming impression I gain from the London paper is that Hessen had decided “to do a Marxist job” on Newton in terms relating physics to economic trends, while imbedding in the paper a separate, more subtle message about the relationship of science to ideology. He must have realized that by interpreting Newton in elementary Marxist economic terms, he could accomplish two important goals: first of all, he could demonstrate his Marxist orthodoxy, something being seriously questioned by his radical critics back in the Soviet Union; second, he could, by implication, defend science against ideological perversion by pointing to the need to separate the great merit of Newton’s accomplishments in physics from both the economic order in which they arose and the philosophical and religious conclusions which Newton and many other people drew from them.

If so, Hessen’s talk represented a scientist’s last desperate effort to preserve his life and his Marxist faith by exposing the absurdity of the party line. It failed, and Hessen was crushed. Yet his paper lived on, through decades of heedless scholarship on the part of radical academics who neither got the joke nor much cared about the fate of its author. Thousands of academic papers were published supporting precisely the points that Hessen had lampooned—that science is socially conditioned and ought to be subordinated to state control. Many teachers and students today continue to believe that scientific findings are politically contaminated and that there is no objective reality against which to measure their accuracy. In the postmodernist view any text, even a physics paper, means whatever the reader thinks it means. What matters is to be politically correct. The term comes from Mao’s Little Red Book.

The postmodern assault on science involved two main campaigns. One was to undermine language—to “deconstruct” texts—by claiming that what a scientist or anybody else writes is really about the author’s (and the reader’s) social and political context. Central figures in this effort included the German philosopher Martin Heidegger, the French philosopher Jacques Derrida, and the Belgian literary critic Paul de Man. The other campaign took on science more directly, as a culturally conditioned myth unworthy of respect. Here an influential figure was the Austrian philosopher Paul Feyerabend, who drew on the relatively liberal works of Thomas Kuhn and Karl Popper.

Derrida got the term “deconstruction” from Heidegger (who got it from a Nazi journal edited by Hermann Göring’s cousin, and used it to advocate the dismantling of ontology, the study of the nature of being) but found it difficult to define: “A critique of what I do is indeed impossible,” Derrida declared, thus rendering his work immune to criticism. In essence, deconstructionism demands that the knowing reader tease out the meanings of texts by discerning the hidden social currents behind their words, emerging with such revelations as that Milton was a sexist, Jefferson a slave driver, and Newton a capitalist toady.

The doctrines of Heidegger and Derrida were imported into America by de Man, who as a faculty member at Yale became, in the estimation of the literary critic Frank Kermode, “the most celebrated member of the world’s most celebrated literature school.” His was the appealing story of an impoverished intellectual who had fought for the Resistance during the war but was too modest to say much about it (except that he had “come from the left and from the happy days of the Front populaire”), was discovered by the novelist Mary McCarthy and taken up by New York intellectuals while working as a clerk in a Grand Central Station bookstore, and went on to become one of America’s most celebrated professors, demolishing stale shibboleths with proletarian frankness. “In a profession full of fakeness, he was real,” declared Barbara Johnson, famous for having celebrated deconstructionism in a ripe sample of its own alogical style:

Instead of a simple “either/or” structure, deconstruction attempts to elaborate a discourse that says neither “either/or,” nor “both/and” nor even “neither/nor,” while at the same time not totally abandoning these logics either. The very word deconstruction is meant to undermine the either/or logic of the opposition “construction/ destruction.” Deconstruction is both, it is neither, and it reveals the way in which both construction and destruction are themselves not what they appear to be.

However, de Man was a fake. Soon after his death in 1983, a young Belgian devotee of deconstruction discovered that de Man, rather than working with the Resistance and coming “from the left,” had been a Nazi collaborationist who wrote anti-Semitic articles praising “the Hitlerian soul” for the pro-Nazi journal Le Soir. Moreover he was a swindler, a biga-mist, and a liar, who had ruined his father financially then fled to America, promising to send for his wife and three sons when he found work but choosing instead to marry one of his Bard College students.

When these discomfiting facts emerged, Derrida came to his friend de Man’s defense but in doing so inadvertently called attention to deconstructionism’s moral abstruseness. “The concept of making a charge itself belongs to the structure of phallogocentrism,” Derrida wrote dismissively. Nor was he alone in flying to the defense of de Man—who had presciently exonerated himself in advance, writing, in a 1979 study of Rousseau, “It is always possible to excuse any guilt, because the experience always exists simultaneously as fictional discourse and as empirical event and it is never possible to decide which one of the two possibilities is the right one.” Years later, radical academics were still teaching de Man as if he were something other than a liar, a cheat, and a Nazi propagandist. As Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont remind us, in their book Fashionable Nonsense, “The story of the emperor’s new clothes ends as follows: ‘And the chamberlains went on carrying the train that wasn’t there.’”

The foundations of radical academic thought were further undermined when disquieting evidence came to light concerning Heidegger, the philosopher whose work stood at the headwaters of Derrida’s deconstructionism, Jean-Paul Sartre’s existentialism, and the structuralism and poststructuralism of Claude Levi-Strauss and Michel Foucault. Regarded in such circles as the greatest philosopher since Hegel, Heidegger celebrated irrationalism, claiming that “reason, glorified for centuries, is the most stiff-necked adversary of thought.” He flourished in wartime Germany, being named rector of Freiburg University just three months after Hitler came to power. The postmodernist party line was that Heidegger might have flirted with Nazism but had been a staunch defender of academic freedom. In 1987, a former student of Heidegger’s found while searching the war records that Heidegger had joined the Nazi party in 1933 and remained a dues-paying member until 1945—signing his letters with a “Heil Hitler!” salute, declaring that der Führer “is the German reality of today, and of the future, and of its law,” and celebrating what he called the “inner truth and greatness of National Socialism.”

As might be expected of a dedicated Nazi holding a prominent university position, Heidegger worked enthusiastically to exclude Jews from academic life. He saw to it that the man who had brought him to Freiburg University—his former teacher Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology—was barred from using the university library because he was Jewish. He broke off his friendship with the philosopher Karl Jaspers, whose wife was Jewish; secretly denounced his Freiburg colleague Hermann Staudinger, a founder of polymer chemistry who would win the Nobel Prize in 1953, after learning that Staudinger was helping Jewish academics hang on to their jobs; and scotched the career of his former student Max Müller by informing the authorities that Müller was “unfavorably disposed” to Nazism. Heidegger lied about all this after the war, testifying to a de-Nazification committee in 1945 that he had “demonstrated publicly my attitude toward the Party by not participating in its gatherings, by not wearing its regalia, and, as of 1934, by refusing to begin my courses and lectures with the so-called German greeting [Heil Hitler!]”—when in fact that is exactly how he started his lectures, for as long as Hitler remained alive. In a similarly revisionist vein, Heidegger rewrote his 1935 paean to the “inner truth and greatness of National Socialism,” making it appear to have been an objection to scientific technology—an alteration that he repeatedly thereafter denied having made.

Particularly distressing, considering the subsequent spread of Heidegger’s fame through the American academic community, was his attitude toward the relationship of universities to the political authorities. Upon becoming rector of Freiburg, Heidegger declared that universities “must be…joined together with the state,” assuring his colleagues that “danger comes not from work for the State”—an astounding thing to say about the most dangerous state ever to have arisen in Europe—and urging students to steel themselves for a “battle” which “will be fought out of the strengths of the new Reich that Chancellor Hitler will bring to reality.” Suiting his actions to his words, Heidegger changed university rules so that its rector was no longer elected by the faculty but rather appointed by the Nazi Minister of Education—the same Dr. Rust who in 1933 decreed that all students and teachers must greet one another with the Nazi salute. Heidegger was rewarded by being appointed Führer of Freiburg University, a step toward what seems to have been his goal of becoming an Aristotle to Hitler’s Alexander the Great.

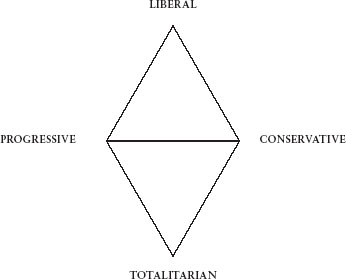

These and other revelations about the fascist roots of the academic left, although puzzling if analyzed in terms of a traditional left-right political spectrum, make better sense if the triangular diagram of socialism, conservatism, and liberalism is expanded to form a diamond:

Such a perspective reflects the fact that liberalism and totalitarianism are opposites, and have an approximately equal potential to attract progressives and conservatives alike. (Try guessing who, for instance, said the following: “Science is a social phenomenon…limited by the usefulness or harm it causes. With the slogan of objective science the professoriate only wanted to free itself from the necessary supervision of the state.” Lenin? Stalin? It was Hitler, in 1933.) The diagram also suggests why American liberals did at least as much as conservatives to expose the liabilities of communism, even when the USSR and the United States were wartime allies. In 1943, two liberal educators, John Childs and George Counts, cautioned their colleagues that communism “adds not one ounce of strength to any liberal, democratic or humane cause; on the contrary, it weakens, degrades or destroys every cause that it touches.” The following year, the liberal political scientists Evron Kirkpatrick and Herbert McClosky sought to correct procommunist sympathies among leftist academics by pointing out similarities between the Nazi and communist regimes—e.g., that both prohibited free elections, freedom of speech, and freedom of the press; were dominated by a single political party whose views were broadcast by an official propaganda network and enforced by state police; and were dedicated to expansion of their power by force. Because liberalism is diametrically opposed to totalitarian rule, these and many other liberals were alert to fallacies of illiberal rule that escaped those leftists and rightists whose focus on promised results blinded them to present dangers.

How did academics fall victim to authoritarian dogma? The story centers on the traumas that befell France between the two world wars. The Great War left France with over a million dead, a million more permanently disabled, and a faltering economy. The Great Depression—made worse by Premier Pierre Laval’s raising taxes and cutting government spending—brought the economy to its knees, while increases in immigration, intended to bolster France’s war-depleted workforce, spurred resentment among workers who complained that foreigners were claiming their jobs. These woes were then capped by the unique humiliations of France’s rapid surrender to Hitler’s army and its establishment of the collaborationist Vichy government. A consensus arose among French academics that democracy was bankrupt and socialism their salvation. Some went over to the Nazis, who had the temporary advantage of seeming to be the winning side. Others adhered to communism, which became the winning side on the Eastern Front and had gained respectability by virtue of the fact that many members of the French Resistance were communists. The resulting clash of right-wing and left-wing French intellectuals drove political dialogue toward illiberal intemperance. As the social scientist Charles A. Micaud observes:

A counter-revolutionary extreme right and a revolutionary extreme left, pitted against each other, emphasized the respective values of authority and equality at the expense of liberty…. Each coalition was kept together, not by positive agreement on a program, but by the fear inspired by the other extreme.

The result was what Micaud calls “a strong disloyal opposition” characterized by a contempt for liberalism and a romantic attachment to revolution. “Left and right alike felt a distaste for the lukewarm and were fascinated by the idea of a violent relief from mediocrity,” writes the historian Tony Judt. The faith of French intellectuals in the power of revolution took on the trappings of a religion. Micaud:

This psychological interpretation of the need for revolution explains reactions that would be incomprehensible at a more rational level—the impossibility of expecting reasonable and calm answers to certain pertinent questions concerning capitalism or socialism, reformism or communism; the impossibility of penetrating the charmed circle of a priori assumptions, based on faith, with arguments of fact and logic, the “moral and intellectual absolutism” characteristic of many left-wing intellectuals; a curious absence of any realistic analysis of economic and social problems; an extreme symbolism that abstracts reality to the point of meaninglessness or to what would seem, at times, intellectual dishonesty.

In terms of logic, postmodernism maintained that inasmuch as science involves induction, and induction is imperfect, science is imperfect. But since everybody already knew that—scientists claimed perfection for neither their results nor their methods—it was necessary to portray scientific research as not only imperfect but somehow subjective. This involved making much of there being no single, monolithic scientific method. Theoretical physicists work rather differently from molecular biologists, and both work differently from the anthropologists and sociologists upon whose examples the postmodernists tended to rely. (Many radical critiques of science acquire a certain coherence if read as describing social scientists, dispatched from the first world to study the third.) Hence the postmodernist argument took on the following odd, and oddly popular, form: There is no single scientific method, replicated in every detail in every science, and therefore—here comes quite a leap—scientific results are no more trustworthy than those obtained through any other procedure. Such arguments often began by trying to celebrate the prescientific beliefs of indigenous peoples, but soon ripened into attacks on science and logic so sweeping as to destroy the grounds on which the postmodernists themselves could critique any system of thought whatsoever.

The foundations of this endeavor were laid, to some extent unwittingly, by the Viennese philosopher Karl Popper and the American historian of science Thomas Kuhn.

Popper embraced Marxism as a youth but later evolved to a more liberal stance, eventually expressing dismay that liberal democracy was being “so often betrayed by so many of the intellectual leaders of mankind.” His studies of science wrestled with the “problem of induction.” Briefly put, this is the problem that if you observe a thousand white swans and then publish a paper declaring that all swans are white, you will be proven wrong should a black swan turn up. David Hume identified the problem of induction in 1739. His point was that if all knowledge is based on experience—as the empiricists maintain—then all conclusions, from the colors of swans to the laws of thermodynamics, are vulnerable to disproof.

It cannot be said that physicists lose much sleep over the problem of induction. They neither require, nor have they often resorted to, the claim that their findings are absolutely determined. Even the laws of science—the highest category of scientific near-certitude—are to some degree provisional. If you open a bottle of perfume and leave it in a sealed room, the perfume will eventually evaporate. Once that has happened and the perfume molecules are adrift throughout the room, they will never get back into the bottle unless a lot of work is exerted to bring about that result. This situation is expressed quantitatively in the laws of thermodynamics, which are rooted in calculations of probability. What those calculations say is not that it is impossible for the molecules to return to the bottle of their own accord, but that it is highly unlikely—so unlikely that if the entire observable universe consisted of nothing but open perfume bottles sitting in sealed rooms, not one bottle anywhere would yet have refilled itself with perfume. That’s certain enough to satisfy most physicists.

In the social sciences, however, the limitations of induction come up more often, and have to do less with black and white swans than with shades of gray. Political opinion polling, for instance, is an empirical, highly competitive business—if your company fails to make reliable predictions of election results, it will lose clients to competing firms that do a better job—so pollsters pay a lot of attention to improving their sampling techniques. They don’t need to be told that induction is less than perfect; they swim against the currents of inductive uncertainty all the time. But to claim that these limitations invalidate science is like saying that the sun is not spherical because it is not perfectly spherical. Science studies nature, and nothing in nature is ever a perfect anything.

Philosophers, however, tend to see things differently; in a sense, that’s their job. Popper came up with the salient point that scientific hypotheses may be distinguished from other sorts of pronouncements by virtue of their being vulnerable to disproof. The statement that “man is born unto trouble, as the sparks fly upward” (Job 5:7) is not scientific, since it is too vague to be disproved, whereas the statement that “the charge of the proton is 1.602176487×10–19 Coulombs to within an error bar e” is scientific, since it can be checked experimentally and might turn out to be wrong (although that would be a very black swan indeed). Popper’s intention was mainly to debunk “pseudoscientific theories like Marx’s [and] Freud’s,” but the postmodernists made a bonfire of its little spark, arguing that if scientific findings are falsifiable then they are no better than the findings of any other endeavor—about which more in a moment. But first, Thomas Kuhn.

Kuhn studied physics at Harvard before becoming a historian of science. He was fascinated by revolutions. His first book, The Copernican Revolution, examined how Copernicus had shown that a sun-centered model of the solar system could fit the observational data as well as did the earth-centered cosmology of Claudius Ptolemy that had preceded it. His second, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, extended the concept to science more generally. In it, Kuhn stressed the provisional nature of scientific knowledge—as scientists themselves often do, referring for instance to Darwin’s theory of evolution. Kuhn depicted the history of science as consisting of long, relatively docile periods of normalcy punctuated by spasms of revolutionary change. Kuhn called such changes “paradigm shifts.” He defined paradigms as developments “sufficiently unprecedented to attract an enduring group of adherents away from competing modes of scientific activity [and] sufficiently open-ended to leave all sorts of problems for the redefined group of practitioners to resolve.” As an example, he cited the discovery of the planet Uranus by the British astronomer William Herschel in 1781. On more than a dozen prior occasions, Kuhn pointed out, other astronomers had observed Uranus without recognizing that it was a planet. When Herschel spotted Uranus through his telescope, he noted that it looked like a disk rather than a starlike point. He then tracked it for several nights and found that it was slowly moving against the background stars. He thought that the object might be a comet, but further studies of its orbit revealed that rather than crossing the orbits of the planets, as most visible comets do, it remained outside the orbit of Saturn. Only at that point did Herschel conclude that it was indeed a planet. Writes Kuhn, “A celestial body that had been observed off and on for almost a century was seen differently after 1781 because…it could no longer be fitted to the perceptual categories (star or comet) provided by the paradigm that had previously prevailed.” This interpretation is very forced. There was little or no such thing as a “star or comet” paradigm against which Herschel had to battle. What happened was that Herschel, an exceptionally sharp-eyed observer using a finely honed telescope that he had constructed with his own hands, was able to discern the disk of Uranus, as other astronomers who lacked his skill and his optics had not. (Viewed through inferior optics, the stars all look like blobs rather than points.) Having made that observation, Herschel checked to see if the object was moving against the stars, as a planet or comet would do. When he found that it was moving, he hypothesized that it was a comet. He had at least two good reasons for doing so: Comets were being discovered all the time, whereas nobody in all recorded history had yet discovered a planet; and to have claimed that it was a planet would have also been to insist that he, Herschel, should be accorded worldwide fame—not the sort of thing that a modest, responsible scientist would want to assert on his own behalf without stronger evidence. When, in the normal course of scientific investigation, the object’s orbit revealed it to be a planet, it was so designated. Herschel’s discovery was important, but few informed historians aside from Kuhn have found it useful to claim that it involved some sort of shift in the scientific gestalt or that it opened scientists’ eyes to phenomena about which they had previously been blind.

Consider the subsequent discovery of Neptune, the next planet out from Uranus, in 1846. Neptune’s existence was inferred from anomalies in the orbit of Uranus. Consulting these calculations, astronomers in Germany and England looked for a new planet in the particular part of the sky to which the mathematicians had pointed them. One such observer, James Challis in Cambridge, actually spotted Neptune through his telescope and noted that it seemed to have a disk—but he failed to examine it at a higher magnification or to follow up on his observation, leaving the discovery solely to the Germans. Evidently Challis hadn’t received the Kuhnian memo: A half century after a paradigm shift was supposed to have changed the way astronomers looked at the sky, they were still apt to fall into the same lapses that, for Kuhn, ought by then to have become obsolete.

Like so many of the postmodernist “science studies” that followed in its wake, Kuhn’s thesis was accurate only insofar as it was trivial. It may be useful to speak in terms of scientific revolutions, but they are rare and getting rarer (there has not been one that satisfies Kuhn’s criteria in over a century), they do not result in the discrediting of all prior knowledge in the field (the Apollo astronauts navigated to the moon using Newtonian dynamics, having minimal recourse to Einstein’s relativity), and it is usually extraneous to invoke new paradigms to explain why scientists thereafter are able to discern phenomena they had previously ignored. The physicist Paul Dirac in 1928 derived a theoretical equation for the electron which accurately described how electrons couple to electromagnetic fields. The Dirac equation also implied the existence of an unknown, oppositely charged particle, the positron, that was soon thereafter discovered. Dirac’s name would be more widely known today had he predicted that positrons existed, but he downplayed that aspect of his own equation because he was unsure whether it was real or just a mathematical artifact. (Asked years later about his reticence, Dirac attributed it to “pure cowardice.”) It is unclear how describing this as a paradigm shift adds to Dirac’s own characterization of it, and anyway the facts differ substantially from Kuhn’s prescription. Carl Anderson in 1932 discovered positrons accidentally, not because Dirac had predicted their existence, so once again the absence of a new “paradigm” failed to retard scientific progress.

Notwithstanding its severe limitations, Kuhn’s thesis—which he immodestly described as “a historiographic revolution in the study of science”—was popular enough to make The Structure of Scientific Revolutions the most cited book of the twentieth century; even Science magazine called it “a landmark in intellectual history.” Students intimidated by science were relieved to learn, as the historian Gerald Holton summarized their impression of Kuhn’s argument, that “science provides truths, but now and then everything previously known turns out to have been entirely wrong, and a revolution is needed to establish the real truth.” (Why bother to learn science, if it’s all soon to change anyway?) Cultural critics were delighted to be reassured that sociological interactions among scientists had so great an influence; if scientific findings are but social constructions, then perhaps they are no better than any other. Through that imaginary breach flooded such oddities as “feminist algebra,” “nonwestern science,” and the assertion that it was parochial to prefer particle physics to voodoo. Kuhn’s Structure became the indispensable starting point for academics out to diminish science without learning any.

The radicals wove Kuhn and Popper into an academic version of bipolar disorder: Everything real was depressing, everything desirable imaginary. Real science needed to be replaced by a “particularist, self-aware” science that would yield different answers depending on who—a woman, say, or a Sufi, or an Aborigine—was asking the questions. As the science critics could formulate no such particularized sciences, they fell back on celebrating their efforts to do so, filling their papers with self-congratulatory descriptions of how hard they were working to shuffle ideas around and create new projects. As the historian Robert Conquest observes, postmodernist theories “are complex, and deploying them is often a complicated process, thus giving the illusion that it is a useful one.”

The Austrian philosopher Paul Feyerabend, inspired by Popper, crafted a critique of science that was for decades regarded as significant. A colorful figure—he was a German army veteran who walked with a limp, having been shot in the spine during a quixotic attempt to direct traffic in a combat zone on the Russian front, the wound rendering him permanently impotent although he went on to be married four times—Feyerabend was studying in postwar London when he happened to attend a lecture by Popper. “I am a professor of scientific method,” Popper began, “but I have a problem: There is no scientific method.” Popper was being hyperbolic, but Feyerabend inferred that having no one method meant having no method whatever. “Successful research does not obey general standards; it relies now on one trick, now on another,” Feyerabend wrote, adding, in breathless italics, “The events, procedures and results that constitute the sciences have no common structure…. Scientific successes cannot be explained in a simple way.” But this was just an elaborate way of saying that scientific creativity, like all creativity, is somewhat mysterious.

Like many philosophers lacking firsthand experience in scientific research, Feyerabend thought of science as a species of philosophy, centered on logic and only incidentally entangled in the actual workings of the material world. (He boasts in his autobiography of having set a roomful of astronomers squirming by lecturing them on cosmology “without mentioning a single fact.”) Starting from this flawed premise, he imagined that science needed to be freed “from the fetters of a dogmatic logic,” and that this meant deconstructing scientific language. “Without a constant misuse of language there cannot be any discovery, any progress,” he claimed, sounding rather like Lenin. “We can of course imagine a world where…scientific terms have finally been nailed down [but] in such a world only miracles or revelation could reform our cosmology.” That is demonstrably false. Scientific terms get nailed down all the time, yet this has not inhibited the progress of cosmology. For example, astronomers studying the expansion of the universe discovered in 1997 that, to their astonishment, the cosmic expansion rate is accelerating. The enormous force responsible for the acceleration was subsequently, and rather unhelpfully, named “dark energy,” but that was after the fact. The discovery that cosmic expansion is speeding up was not made by changing prior scientific terminology, but by employing existing terminology, tools, and concepts, a feat that Feyerabend claimed was impossible.

What Feyerabend was really attempting was to discredit Enlightenment values, which the radicals regarded as a mask for power politics. “I recommend to put science in its place as an interesting but by no means exclusive form of knowledge that has many advantages but also many drawbacks,” he wrote.

There is not one common sense, there are many…. Nor is there one way of knowing, science; there are many such ways, and before they were ruined by Western civilization they were effective in the sense that they kept people alive and made their existence comprehensible.

This charge should be examined closely, given that it has been widely entertained among Westerners lamenting the sins of colonialism. Feyerabend states that the ways of knowing of indigenous peoples “kept people alive.” But people are kept alive by traditional ways of knowing only to the degree that such ways are themselves scientifically valid. If a medicine man gives you an herb that actually cures your disease, the cure is scientifically defensible—and scientists have learned a lot about herbs from just such individuals—but if the herb is of no empirical value, the only thing that may keep you alive is the placebo effect of your faith in the treatment, which improves the health of something like a fifth to a third of patients in Western doctors’ offices and thatched huts alike. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami killed over 200,000 persons, but spared those whose traditions had alerted them to head for higher ground when an earthquake struck. The tradition worked because it was empirically valid, having been inducted by ancestors who inferred a causal relationship between earthquakes and tsunamis. Those whose traditions asserted something empirically invalid—say, that an earthquake means we’ve offended the sea gods, so we should all wade into the ocean and pray—would have been following bad advice, even though it too was a “way of knowing.” Feyerabend’s other claim for indigenous knowledge, that it “made their existence comprehensible,” is flatly patronizing. Should doctors deny malaria vaccines to indigenous peoples on grounds that the local mythology claims that malaria is contracted by working too hard in the fields, or is a punishment wrought by the gods? Granted, some field researchers and physicians may have given short shrift to the knowledge and wisdom of the peoples they studied and treated. But it is a wild exaggeration to write, as Feyerabend did, that “the ‘progress of knowledge and civilization’—as the process of pushing Western ways and values into all corners of the globe is being called—destroyed these wonderful products of human ingenuity and compassion without a single glance in their direction.”

Although he represented himself as a friend to freedom and creativity, Feyerabend supported repressive governmental controls on scientific research. He even imagined that such interventions would open up science to new modes of thinking—a process that he called “proliferation”:

It often happens that parts of science become hardened and intolerant so that proliferation must be enforced from the outside, and by political means. Of course, success cannot be guaranteed—see the Lysenko affair. But this does not remove the need for non-scientific controls on science.

His sole example of such a success was a 1954 campaign by the British Ministry of Health to stress “traditional medicine,” such as acupuncture, over Western “bourgeois science.” Feyerabend credited this Marxist-inspired project with “making a plurality [actually a duality] of views possible.” By these lights, Hitler could have increased scientific open-mindedness and creativity by ordering German astronomers to validate his pet theory that the earth was hollow. Feyerabend’s offhand dismissal of the Lysenko affair, which involved the persecution of talented scientists whose views deviated from the party line, was consistent with his generally opaque ethical views. These were his remarks on the Chinese Cultural Revolution, in which scientists and intellectuals were murdered and cultural artifacts wantonly destroyed:

Scientists are not content with running their own playpens in accordance with what they regard as the rules of scientific method, they want to universalize these rules, they want them to become part of society at large and they use every means at their disposal—argument, propaganda, pressure tactics, intimidation, lobbying—to achieve their aims. The Chinese communists recognized the dangers inherent in this chauvinism and they proceeded to remove it. In the process they restored important parts of the intellectual and emotional heritage of the Chinese people and they also improved the practice of medicine. It would be of advantage if other governments followed suit.

When Feyerabend’s book Against Method was first published, in 1975, such demonstrations of ignorance and inadvertent cruelty—a philosopher recommending that governments follow the communist example of dispatching gangs of thugs to torment scientists—occasioned what might politely be called negative reviews. Feyerabend protested that the critics weren’t getting his jokes, and that this showed them to be close-minded: “‘New’ points of view,” he sniffed, “…are criticized because they lead to drastic structural changes of our knowledge and are therefore inaccessible to those whose understanding is tied to certain principles.” In a similar vein he complained that his ideas were being embraced by New Age mystics who failed to consider that science does, for some reason, work.

But by then, academics on hundreds of campuses were routinely disparaging science. “Science is not a process of discovering the ultimate truths of nature, but a social construction that changes over time,” wrote the “ecofeminist” Carolyn Merchant of the University of Wisconsin, while the sociologist Stanley Aronowitz, of the City University of New York, declared that “neither logic nor mathematics escapes the ‘contamination’ of the social.” The more hyperbolic the claim, the more celebrated its creator. A particularly astounding hypothesis was forwarded by the sociologist Bruno Latour, who imagined that “since the settlement of a controversy is the Cause of Nature’s representation not the consequence, we can never use the outcome—Nature—to explain how and why a controversy has been settled.” If so, science would amount to no more than a solipsistic game. But it is not so. Prior to the soft landing of space probes on the moon, geologists feared that lunar dust, accumulated over 4.5 billion years of asteroid impacts, might be so deep that the Apollo astronauts would simply sink into it and disappear. The question, debated at length, was settled once robotic probes landed on the moon and did not sink into deep dust; further confirmation came when Neil Armstrong stepped onto the lunar surface and found it firm. But according to Latour this outcome cannot possibly explain “how and why” the controversy came to an end, since the discovery—in this case, that lunar dust is typically only a few inches deep—was somehow a “consequence” of the controversy itself. If science ran by postmodernist rules it could scarcely function at all—which, essentially, was the radicals’ intent. Science, like liberalism, is anathema to ideologues.

The culture wars came to a head, though not to an end, with the Sokal Hoax of 1996. Alan Sokal, a physicist at New York University and one of the few scientists who paid close attention to the postmodernists, wrote a deliberately meaningless paper—rather like the ones created automatically by the online postmodernism generators—and submitted it to the journal Social Text, which published it. The article began with an apt summary of the radical consensus regarding science:

There are many natural scientists, and especially physicists, who continue to reject the notion that the disciplines concerned with social and cultural criticism can have anything to contribute, except perhaps peripherally, to their research. Still less are they receptive to the idea that the very foundations of their worldview must be revised or rebuilt in the light of such criticism. Rather, they cling to the dogma imposed by the long post-Enlightenment hegemony over the Western intellectual outlook, which can be summarized briefly as follows: that there exists an external world, whose properties are independent of any individual human being and indeed of humanity as a whole; that these properties are encoded in “eternal” physical laws; and that human beings can obtain reliable, albeit imperfect and tentative, knowledge of these laws by hewing to the “objective” procedures and epistemological strictures prescribed by the [so-called] scientific method.

What followed was five thousand words of utter gibberish, duly adorned with citations from Kuhn, Feyerabend—and Derrida, rattling on about a (nonexistent) “Einsteinian constant.” Sokal studded the paper with clues that he was joking, writing, among other deliberate howlers, that “the p of Euclid and the G of Newton, formerly thought to be constant and universal, are now perceived in their ineluctable historicity”—which if you stop to think about it, as the editors of Social Text evidently did not, means that even such universal constants as the ratio between the diameter and circumference of a circle, and the rate at which planets orbit stars, depend upon the historical circumstances of their discovery.

“The conclusion is inescapable,” wrote Paul A. Boghossian, a professor of philosophy at New York University, “that the editors of Social Text didn’t know what many of the sentences in Sokal’s essay actually meant; and that they just didn’t care.” What they cared about was ideology. In the end, the postmodernist brew of socialism and cynicism was literally perverse—in the etymological sense of the word, as meaning to look in the wrong direction. Rather than pursuing knowledge about science, radical academics assumed a posture that the mathematician Norman Levitt calls “knowingness, an attitude that gives itself permission to avoid the pain and difficulty of actually understanding science simply by declaring in advance that knowledge is futile or illusory.”

Postmodernism’s lasting legacy—aside from having misled millions of students and made a laughingstock of the academic left—was its call to “democratize” science. This sounds nice, but in practice usually means wielding the power of the state to restrict scientific research. Hence it was not surprising that the “democratization” of science gained favor among authoritarian political thinkers of many stripes, from British socialists to right-wing Indian theorists to the Bush White House. When the mayor of Cambridge, Massachusetts, sought in 1976 to ban recombinant DNA research at Harvard, he exclaimed, “God knows what’s going to crawl out of the laboratory!” The university prevailed, and as the biologist Carl Feldbaum reported, a generation later:

What eventually “crawled out of the laboratory” was a series of life-saving and life-enhancing medications and vaccines, beginning in 1982 with recombinant insulin and soon followed by human growth hormone, clotting factors for hemophiliacs, fertility drugs, erythropoietin, and dozens of other additions to the pharmacopeia.

When confronted with fear tactics based on Faustian science-fiction fantasies, a useful exercise is to ask yourself which facts, adduced by science in the past, you would prefer had never been learned. The list is unlikely to be long.

How did it come to pass that so many teachers and students, in some of the freest and most scientifically accomplished nations in the world, entertained such an illiberal, illogical, and politically repressive account of the relationship between science and society? Part of the answer may be that universities generally, and humanities departments in particular, are more backward than is universally recognized. For most of their history, universities functioned primarily as repositories of tradition. It was professors, not priests, who refused to look through Galileo’s telescope, and who drove genuinely progressive students like Francis Bacon and John Locke to distraction with their endless logic-chopping and parsing of ancient texts. Similarly it was twentieth-century humanities professors who, confronted with the glories of modern science and the triumph of the liberal democracies over totalitarianism, responded by denigrating virtually every political philosophy except totalitarianism. Campus enthusiasm for authoritarian rule today is predominantly leftist (one gets an impression that professors and students who live in university housing and eat at the commons think that everybody else should also enjoy life in a socialist paradise), but historically it has often come from the right as well. In 1927, years before Hitler came to power, 77 percent of the German student organizations were sufficiently in tune with the Nazis to ban non-Aryans from joining their clubs; by 1931, university support for Hitler was twice that of the German population at large. The Nazis book-burnings of 1933—where the works of Einstein, Thomas Mann, and H. G. Wells went up in flames—were staged by students and professors out to shape up Germany’s youth for the trials ahead. The villains of the piece for right-wing socialists were Jews and bankers; for today’s leftists they are big corporations and globalization. “Globalization has produced a world economic system and trade laws that protect transnational corporations at the expense of human life, biodiversity, and the environment [and by] greater levels of unemployment, inequality, and insecurity,” reads a paper selected at random from the postmodernist literature. No facts are presented to support this claim, nor need they be. The statement is an assertion of shared belief, equivalent to the ritual incantations uttered to reassure the faithful at the outset of a religious service.

To say all this is not to condemn academics generally. The proponents of antiscientific, illiberal academic fads were mostly lackluster scholars, many of whom (e.g., Derrida, de Man, and Feyerabend) traded on their outsider status, while their defeat was wrought principally by liberal academics—debunkers like Paul R. Gross and Norman Levitt, whose book Higher Superstition critiqued the postmodernists; Frederick Crews of the University of California, Berkeley, English department, who lampooned them in his bestselling Postmodern Pooh; and Allan Bloom of the University of Chicago, whose The Closing of the American Mind sold a million copies. (Bloom was pilloried by leftist critics as politically conservative, although he was a liberal Jewish homosexual who wrote his book at the behest of his friend the novelist Saul Bellow, and who protested, about as plainly as possible, “I am not a conservative.”)

It may be useful to summarize the campaigns of the radical academics in terms of their principal errors. First, they ignored science as a source of knowledge and instead depicted it as a source of power, a distortion which ultimately led them to discount the validity of all objectively verifiable knowledge. Second, they thought that since scientific research is a social activity, the knowledge it produces must be nothing more than a social construct; this was like claiming that if various teams of mountaineers climb the north face of Eiger via different routes, there must be no real Eiger at all. Finally, they turned their back on learning. This may seem an odd thing to say of college professors—but academics, like most people, tend to form their political beliefs early on and then cease examining them, settling instead into blinkered judgments about how to realize their presumptively superior goals. The result is an academic shell game that was already well under way when Galileo, centuries ago, noted that it was the habit of many professors “to make themselves slaves willingly; to accept decrees as inviolable; to place themselves under obligation and to call themselves persuaded and convinced by arguments that are so ‘powerful’ and ‘clearly conclusive’ that they themselves cannot tell the purpose for which they were written, or what conclusion they serve to prove!”

Perhaps the most sympathetic thing to be said of the postmodernists and their sympathizers is that in witnessing the environmental degradation and decline of indigenous cultures that attended the postwar rise in global technology and trade, they feared that the wonderful diversity of our world was shrinking into something akin to the “single vision” of William Blake’s Newton. Such concerns are not baseless, but the worst way to address them is by championing subjective ways of knowing over objective scientific knowledge. “Epochs which are regressive, and in the process of dissolution, are always subjective,” noted Goethe, “whereas the trend in all progressive epochs is objective…. Every truly excellent endeavor turns from within toward the world [and is] objective in nature.” A recent image transmitted from Mars showing a tiny blue crescent Earth adrift in the blackness of space reinforces the sentiment declared a half century ago by the eminent bluesman Huddie Ledbetter, known as Leadbelly:

We’re in the same boat, brother

We’re in the same boat, brother

And if you shake one end

You’re going to rock the other

It’s the same boat, brother.