‘Look on my Works’: Ozymandias, King of Kings

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert … Near them on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal these words appear:

‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

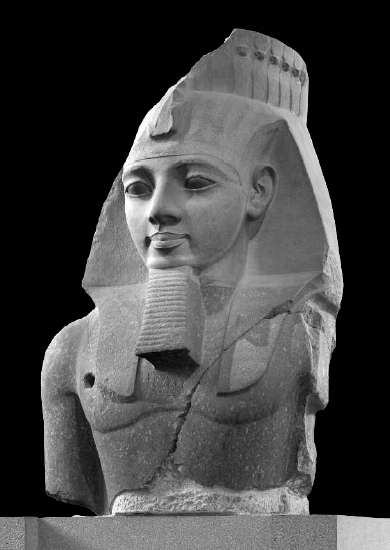

‘Ozymandias’ was written in 1818 and it was seemingly inspired by a visit which Percy Bysshe Shelley made to the British Museum to see the colossal statue of Ramesses II which had been brought there from Egypt a few years previously. This statue certainly astounded all who saw it with the sense of power which emanated from it. It told early nineteenth-century Britons of a great kingdom which had flourished when Britain had still been in the Stone Age.

Ramesses reigned from 1279 to 1213 BC, ruling over a powerful and prosperous kingdom. He was not backward in claiming his share of the credit for this and he left a legacy in which he was the central character and largely the instigator of all that was achieved during this ‘Golden Age’ of ancient Egypt. He clearly intended that the knowledge of his achievements should be widely known both to his own people and to future generations. An important feature of this self-aggrandizement was his new capital, Pi-Ramesses Aa-nakhtu – meaning the House of Ramesses II – but his most monumental display of power lay elsewhere. He had huge statues of himself placed widely throughout his domains, most significant among which was the vast complex at Thebes known today as the Ramesseum. This complex included a temple, a palace, a treasury and other buildings as well as large numbers of statues. Everything was designed to demonstrate the greatness of the pharaoh and it was here that the statue was found in the early nineteenth century. Originally discovered by Napoleon’s Egyptian expedition of 1798–1801, it was the British, one of the principal victors in the Napoleonic wars, who eventually had it removed to their own capital city.

The statue of Pharaoh Ramesses II in the British Museum.

With the Ramesseum the pharaoh sought to display himself as the supreme ruler, but it had another function and this was to present in stone the essentials of successful kingship. Paramount among these was that the king should be at all times visible to his subjects and this Ramesses sought to do through the multiplication of statues of himself throughout his kingdom. There was also the necessity for the king to have divine blessing for his endeavours, and this was ensured by the fact that in ancient Egypt the pharaoh was himself divine. A pronouncement in stone by Ramesses was, ‘Listen … for I am Râ, lord of heaven, come to earth.’ Braudel points out that this divinity was translated into the size and dignity of the monarch as he would have appeared in his statues.1 It was also essential that he behave as a strong ruler and have success against his foreign enemies. Ensuring prosperity was necessary too, in case of revolt by disaffected subjects, but that had to be a more long-term policy objective. In the words of Neil MacGregor, the director of the British Museum, ‘The whole of the Ramesseum conveyed a consistent message of imperturbable success.’2

MacGregor considers that Shelley’s poem was actually less a meditation on imperial grandeur than on the transience of earthly power. However, it is surely both because the poet stresses that the statue conveys powerfully the grandeur of earthly power which preceded its fall. During the time of this grandeur Egypt was one of the great civilizations of the world and its influence was widely felt. Despite the transience expressed in the conclusion – ‘The lone and level sands stretch far away’ – ancient Egypt had a profound effect on the whole story of humanity. This was the true legacy of Ramesses II and of the whole of Egyptian history, and the colossal statue in the desert is to be seen as a symbol of this as well as the desolate remains of a vanished empire.

Just as Ramesses emphasized the necessity for kings to be visible, such visibility was intended to convey something specific and this also was accomplished through the medium of stone. ‘The frown’ and the ‘sneer of cold command’, as Shelley put it, were intended, in the poet’s imagination, to be displays of power.3 The citizens of the budding British Empire were certainly astounded and amazed by the sense of power conveyed by this ancient statue. It may have been a power which had by then long vanished, but it had clearly been dominant in the world of its time. And 3,000 years later, early nineteenth-century Britain was about to enter a similar position of dominance but on a far larger world scene. At the end of the same century in which Shelley wrote ‘Ozymandias’, Rudyard Kipling expressed similar sentiments about the British Empire which was by then about to enter its own period of decline.4

The Ramesseum, then, was a kind of textbook for the achievement and retention of power. In many ways, it can be seen as being a kind of stone version of Machiavelli’s Il Principe, instructions forged in stone for would-be imperialists. It is not clear who might subsequently have read these stones because the remains were found deep in the sands of Egypt by later empire builders, but the principles continued to be followed by subsequent power-seekers. The demonstration of overwhelming power, success against enemies and the achievement of prosperity have all been inherent in subsequent imperial ventures. Until the twentieth century at least, divine approval and guidance have also been vital prerequisites and these have been built into the display of power in stone. Most significant of all, perhaps, has been the visibility of the ruler and of the regime in order to demonstrate its close association with the symbols being displayed.

The transposition to stone of a whole imperial edifice has been found throughout the ages to be an effective way both of overawing the populace and intimidating opponents. It can take the form of statues, pictures, temples, palaces and grand edifices of many sorts. Of course, these must also be linked with other elements in the Ramesseum textbook, most notably effective government, heroic achievements and divine support. All combine to produce the necessary justification for the wielding of power. It is in the city as the centre of power that all these things can most effectively be brought together and combined into a powerful statement. It is there also that the power which is displayed can be wielded to greatest advantage.

Power and Domination: Empires and their Symbols

The idea of empire goes far back into human history and is closely associated with the parallel idea of power and the impulse to control and to dominate. Such organized control can first be observed in the cities of the early civilizations originating in the valleys of the Nile, Tigris-Euphrates and Indus. The word ‘civilization’ derives from the Latin civitas – city – and the beginnings of civilization are closely linked with the first cities. Stated in the most general terms, civilization can be defined as the culture of cities.5 There has clearly been a close relationship between the development of humanity, the process of civilizing and the existence of cities.

In the first instance cities came into existence as specialized centres where trade and manufacture could most effectively take place. They were the hubs of the new and more complicated economy which emerged out of the earlier agricultural and pastoral societies. They rapidly accrued other functions and for these, ever more specialist workers were required. Builders were needed for construction and, with increasing sophistication, architects and artists for the design and adornment of churches, temples, castles and the grand palaces of the rich and powerful. This in turn called for the provision of a guaranteed food supply for the increasing numbers who were not actively engaged in producing it. The creation of cities was thus possible only after the development of more intensive food production and this necessitated the domestication of farm animals and the growing of food crops.

Another urban function which appeared early on was the political one, that of the government of the city and of its surrounding region. This required the existence of a state powerful enough to maintain control within the city and to defend it from any external dangers. A class of leaders – kings and princes – arose and their power was associated with that of the cities. They began to build strongholds from which to exercise this power and to ensure their own safety from other would-be leaders who might seek to remove or replace them. The prime external function of these early wielders of power was the defence of their city and its surrounding lands from which came the essential supplies of food and raw materials. As a result of this the whole operation began to assume a wider territorial dimension. Particular cities were chosen as centres for the exercise of power and this was the origin of the ‘capital’ city from which power was exerted over ever-larger territories. To ensure law and order in the city, leaders required enforcers which necessitated various forms of policing. For the defence of their territory, and eventually for its extension, rulers recruited professional armed forces.

It was out of such enlargement of the territory controlled that the idea of empire was born. More and more territory was added to the emerging system both for the purpose of ensuring its security and in order to increase its wealth-producing capacity. Usually this entailed adding areas and populations which initially at least may have had little in common with the original state. This stage of development may have been accomplished by the dominance of one particular city over others but more usually, and especially in Asia, it was accomplished by an external force which was not initially associated with any one particular city. Such force generally emanated from those pastoral societies which continued to exist in areas more suitable for animal herding than for agriculture. The aggressiveness of such rural populations was motivated by a variety of factors, most commonly centring on the improvement of life and conditions. Their naturally nomadic existence, which often led to confrontation between tribes, adapted them both to rapid movement and to the use of weaponry. They were thus well able to attack and subjugate urban societies which, in spite of their wealth, were often quite unable to defend themselves against the onslaught of such powerful invaders.

Throughout human history there have been many types of empire. These can be classified into three types: continental, marginal and maritime. In this classification, the nature of the empire is dependent largely on the geographical conditions in which the imperial process takes place. The terminology used here is derived from the historical geographer Halford Mackinder, who saw the evolution of political systems as closely related to the location and geographical potential of the areas in which they were located.6

The continental empires originated particularly with the peoples of central Asia. These nomadic pastoral societies centred on the steppes, the temperate grasslands of Eurasia, which extend across the continent from the Far East to the Ukraine. From there the pastoral nomadic peoples gradually spread out into the surrounding regions. This spread was caused by many factors, important among which appear to have been population pressures and climate change, both necessitating the search for better grasslands and a more reliable food supply. These societies came to view the sedentary agriculturalists and city-dwellers around the margins of Eurasia with much interest, eventually invading these lands with the aim of being able to have the kind of life which the inhabitants of the cities were perceived to enjoy. An early example of such an aggressive nomadic people were the Assyrians who, in Byron’s poem, ‘The Destruction of Sennacherib’, ‘came down like a wolf on the fold’, overrunning large areas of the Middle East and establishing a powerful imperial state during the early centuries of the first millennium BC. These were then followed by other similar peoples such as the Medes.

The first great empires, then, were established by these ‘imperial nomads’ of central Asia, flourishing in both the Asiatic heartland and in the marginal lands around it. Trading contacts between the marginal lands of west and east took place intermittently over the centuries but often the dangers in central Asia made such trade difficult or even impossible. This eventually motivated the nations of the maritime fringes, in particular those of Europe, to seek safer and more reliable routes to the east, leading to the development of sea routes and the beginning of a new form of empire. From the sixteenth century, maritime imperialism produced the dominant form of empire, and by the nineteenth century these empires, based mainly in Western Europe, covered much of the globe. The great exception to this was the enormous Russian Empire, which was highly continental and was viewed by some analysts as being a kind of successor state to that of the Mongols.3 Its rivalry with the leading maritime empire of the time, the British, led Mackinder to contend that the continental–maritime rivalry was the basic phenomenon of universal history, a contention which has come to be much discussed.

With the approach of the end of maritime imperialism in the middle of the twentieth century, a form of neo-imperialism replaced it. This centred particularly on the United States of America, which was able to build up immense hard and soft power, constituting in effect a non-territorial form of imperialism. It was certainly not empire in the old sense but it represented the projection of power over vast areas, giving the USA the same kind of ascendancy that the old maritime empires held in their heyday. The rivalry between Britain and Russia was now replaced by that between the USA and the Soviet Union. The Cold War between the two continued for most of the second half of the twentieth century. It was not until the twenty-first century that the situation changed radically but, as will be seen, the idea of empire was by no means at an end.

From the outset of the urge to achieve domination over lands and peoples, the symbols for the display of power have always been in evidence. These have been the tangible expressions of the might and magnificence of those who wielded it. It is in cities that such symbols have been brought together most effectively for the purpose of impressing all those who behold them. The principal objective of this was to influence the behaviour of those who beheld it towards a state which possessed such formidable power. While the buildings and their adornments spoke far louder than words, a number of the wielders of power also expressed their meaning and significance. Timur Lenk proclaimed, ‘Let he who doubts our power look upon our buildings.’7

The main purpose of this book is to examine cities which have been built as symbols of empire and so have been used to display ‘power in stone’. While such cities share many common characteristics, there are also many differences among them. Much depends on the nature of the power being wielded and what those who wield it wish to convey. A selection of cities will be examined in terms of what they reveal about power and the way in which they have not only represented it but also contributed to its achievement and maintenance. The cities chosen have been the centres of those great states which have in one way or another been dominating forces in the world of their time. While there have been powerful imperial states in other parts of the world, notably in South America and parts of Africa, it is those of Eurasia which have had the greatest effect on the world as a whole and these will be the main ones to be examined.

The first great power of this type was Persia, and its ceremonial capital Persa, the Greek Persepolis, was the first city to be built specifically for the purpose of displaying power and ensuring that the subject peoples and others were very much aware of it. It was the first capital of a ruler who could assert, with little fear of contradiction, ‘Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair.’