Persepolis and the Persian Empire

Persepolis is one of the very earliest examples of a purpose-built imperial city. Here city, throne and power were fused together in a massive display of the magnificence of the Persian Empire which stretched across the ancient world from the interior of Asia to the shores of the Mediterranean.

The Persians were a nomadic people of Aryan stock who had moved southwards from Central Asia to the Iranian plateau around the end of the second millennium BC. Here they came into contact with a far more advanced people, the Medes, and for a time became their vassals. However, relations deteriorated when the Medes became fearful of the growing power of the Persians and decided that it was time to bring them to heel. The Medes invaded Fars, the Persian homeland in the Zagros mountains, but they were defeated at Pasargadae, south of the Zagros mountains, in 550 BC. The Persian king, Cyrus II, pressed home his advantage and attacked Ecbatana, the Median capital. There was little resistance; the Medes’ empire collapsed and Cyrus became master of an ever-larger territory. By the middle of the sixth century BC, Cyrus can be considered as having become the world’s first true emperor ruling over a huge landmass with a great diversity of peoples. The Persians took over the empire of the Medes and in so doing inherited much of their civilization, including their political organization and the concept of kingship. It was around this time that Cyrus assumed the title of ShahanShah – in ancient Persian ‘Khshayathiyanam Khshayathiya’ – meaning ‘King of Kings’ or ‘Great King’. The Medes always retained a special position in the Persian Empire and in some ways, as has been wryly observed, the Mede empire did not so much come to an end as undergo a change in management. In many statues and bas-reliefs, the Medes are often depicted as being virtual co-rulers of the empire.

Cyrus proved himself to be a good and wise ruler and invariably treated his new subjects with great care. He allowed them to keep their religions and often their political systems as well. Cultural attributes such as language and customs were not interfered with. He is especially remembered with respect and affection in the Bible for having ended the Babylonian captivity of the Israelites and for allowing them to return to their homeland. He even provided assistance for the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem. In this way, the new empire began as a model for future empires but this was, unfortunately, not followed up by Cyrus’s successors. Nevertheless, Cyrus’s dynasty, the Achaemenids, continued to rule the enormous Persian Empire for over 200 years.

Cyrus and his successors realized that the Persian dominance over a large part of the known world of the time required some justification and this was provided by religion. The religion of the Achaemenids was Zoroastrianism, a monotheistic faith that had originated in Persia probably in the seventh century BC. It is believed to have been established by the prophet Zoroaster – or Zarathustra – and it centred on the worship of Ahuramazda, the ‘Wise One’, who was invoked to protect the dynasty. Ahuramazda is usually represented as a winged disc known as the Faravahr, which is the sign of divine glory. The god has also sometimes been represented as a human figure. The Zoroastrian religion involved what has often been thought of as fire worship. In fact it was nothing of the kind and the constantly burning flame in the Zoroastrian temples was there to represent purity and goodness. Ceremonies associated with the eternal flame were central to the rituals of the religion. The whole world was seen as a place of conflict between the good spirit, Spenta Mainyu, and the evil spirit, Angra Mainyu. The rise and success of the Achaemenid dynasty was always closely associated with this religion and its kings were believed to hold their office directly from Ahuramazda. Zoroastrianism always retained a central role in the Persian Empire and in its symbolism. Its importance is seen very clearly in the temples and the inscriptions, in stone and precious metals, which have been found throughout Fars. One of the earliest of these is the gold tablet of King Ariaramnes, an indirect ancestor of Cyrus II, which is known to have been used by Cyrus. It reads as follows:

Ariaramnes, the great King, the King of kings, the King in Persia, Teispes the King and grandson of Achaemenes. Ariaramnes the King says : this country Persia, which I hold, which is possessed of good horses, good men, on me the great God Ahuramazda bestowed [it]. By the favour of Ahuramazda I am the King [in] this country Ariamnes the King says : may Ahuramazda bear me aid.1

It is believed by some historians that Cyrus may have found this tablet and transferred it to his own palace so as to be associated with both Ahuramazda and with his illustrious ancestor.

Early on Cyrus realized the importance of establishing a capital city from which the empire would be ruled and, following his victories in the west, he returned to the Persian homeland of Fars and there embarked on the building of a great palace at Pasargadae. Called in old Persian Pasragarda, meaning ‘camp of the Persians’, this had been an early gathering point for the nomadic Persian tribes. Later it was the site of the great victory over the Medes and so held a position of considerable importance for the Persians. It was seen as being where the Persian Empire had originated and so it rapidly gained the aura of being a sacred place. This was chosen to become Cyrus’s de facto capital for the rest of his reign.

With the death of Cyrus in 528 there was a struggle for the succession and after the short reign of his son Cambyses II, during which the empire continued to grow in size, the throne passed to another branch of the dynasty and Darius I ascended the throne as Great King. While Cyrus had established his capital at Pasargadae, Darius, at first uneasy on his throne, decided that a new purpose-built capital was necessary as a clear demonstration of his own power. The new capital was intended to be a symbol of his own reign and so would distance him from his illustrious predecessor. However, Pasargadae was chosen as the site for the splendid white limestone tomb of Cyrus, built to reinforce its position as the most sacred place for the Persians. Darius chose a site some 50 kilometres to the southwest for his new capital Parsa, which was to become known to the Greeks as Persepolis. It was to be Darius’s greatest building project and the most important symbol of his power.

The city is located on the plain of the Marv-e Dasht, surrounded by high mountains. There appear to have been many reasons for the choice of this particular site for the project, a number of them relating to Persian history and mythology. The tales of the early Persian kings were collected by the great Persian epic poet, Ferdusi, in the Shahnameh, the Epic of the Kings,2 and the area around Persepolis was believed to have had associations with the mythical early kings of Persia. The most important of these was Jamshid, and Persepolis came to be familiarly known as Takht-e Jamshid, ‘The Throne of Jamshid’. The area is also traditionally the home of Rustum, the great Persian hero best known in English through Matthew Arnold’s poem ‘Sohrab and Rustum’. The importance of the sun, and possibly sun worship, can also be seen in the fact that the eastern entrance of the city has been aligned in accordance with the point at which the sun rises over the plain on the summer solstice.

The Tomb of Cyrus the Great at Pasargadae.

As is usually the case, besides these mythical origins, there were also more practical reasons for the selection of the site. The city is located deep in the Zagros mountains at a height of 1,500 m. This would have made it a cooler place for the court to reside than the low-lying land of Mesopotamia where Susa, the city where the day to day running of the empire actually took place, was located. The Persians, who had come from the north, would certainly have preferred this climate and the landscape which surrounded the city would also have been far more congenial to them. The site is also in the valley of the Kor river which would have provided a water supply for the population. As the population grew, ample water could also have been brought down from the surrounding mountains using the intricate system of underground watercourses, the canats, which the Persians had invented. The Kor followed a structural depression in the Zagros which is aligned from northwest to southeast, facilitating communication with Susa and other major centres of the empire. The great axis of communication of the empire was the ‘Royal Road’ which connected Sardis with Susa and was later extended eastwards to Persepolis itself. Finally the importance of the geology cannot be underestimated. The local limestone was easy to work and proved to be an ideal material for the great buildings and monuments of the city. Thus a powerful combination of mythological, historical and geographical factors combined to produce what must have been judged at the time to be the most appropriate site for the location of Darius’s imperial capital.

Work on Persepolis commenced around 520 BC. The city was built on an immense platform which rises some 15 m above the surrounding land. Besides providing stability for the foundations, this would have made the city visible from a greater distance and enhanced its effect on all those who approached it. It was intended above all to be a demonstration of the power of the ShahanShah and of the empire over which he ruled. The main entrance to the city was a flight of steps shallow enough to allow for horses. The whole city was clearly designed with ceremonial purposes very much in mind. Its architecture was derived from that of the conquered peoples, in particular the Assyrians and Babylonians, but it possessed a greater sophistication than either. The brutal ostentation of the Assyrians was softened by the Persian architects.3 At the top of the steps the Gate of All Nations leads into the Apadana, the great hall where many ceremonies of state took place. Another unfinished gate on the same side of the platform leads to the Hall of the Hundred Columns. This was also used for ceremonial purposes. In both of these halls at various times state business would have been conducted and the Great King would have received the homage of his subjects. There was also another massive building on the platform housing the state treasury. As Persepolis was the place where tribute was received, the stored wealth of the dynasty had to be safeguarded. The decoration of the Apadana centred on the twin bull capitals surmounting the pillars which are also to be found elsewhere in the palace.

Among the most telling carvings are those along the wall of the monumental staircase leading up to the Gate of All Nations. Here basreliefs depict the subject peoples climbing the steps and bearing the annual tribute for the Great King. In many cases it is possible to make out from their dress and appearance, and from the gifts they are bearing, the lands from which they came. This is confirmed by the inscriptions found in and around the city. While on the gold tablet of Ariaramnes there was great emphasis on Persia and its virtues, by the time of Darius it was rule over the vast imperial possessions which was being justified. Such an inscription in Persepolis reads:

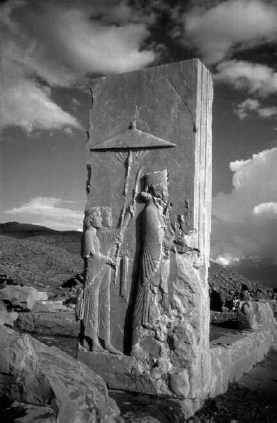

|

Persepolis: Bas-relief of Darius the Great at the head of the Great Stairway. |

I am Darius, the Great King, the King of kings, the King of countries, which [are] many, the son of Hystaspes, an Achaemenian.

Darius the King says: by the favour of Ahuramazda these [are] the countries, which I acquired, with this Persian people, which had fear of me [and] bore me tribute – Elam, Media – Babylonia – Arabia – Assyria – Egypt – Armenia – Cappadocia – Sardis – the Ionians, those of the mainland, and those of the sea – Sagartia – Parthia – Drangiana-Bactria – Sogdiana – Choriasmia – Sattagydia – Arachosia – India – Gandara – the Scythians – Maka.4

On the bas-reliefs the Elamites bring a snarling lioness, the Bactrians a two-humped camel, the Egyptians a bull and the Ethiopians elephant tusks. The Indians have axes and a donkey. The Armenians are shown holding a horse and a large vase and the Assyrians a bull and spears. Undoubtedly many of these things would have been symbolic and the real tribute would be of gold and other precious metals destined for the treasury.

The Medes are also depicted on the bas-reliefs. Although also subjects of the Persians, they were always accorded a privileged position and were respected as the people who had made possible the great achievements of the Persians. The Persian relationship to the Medes was similar to that of the Romans to the Greeks; they were the civilizers and mentors of the imperial people. On the grand staircase, while the Medes had the honour of leading the procession, they are also shown in the role of officials conducting the ceremony.

Halfway up the grand staircase, on the wall behind the guards, was the Faravahr, the winged sun disc and symbol of Ahuramazda. Forbis considered this staircase to be ‘perhaps the most engrossing socio-historical documentary ever put into stone’ and ‘a hand-chiselled filmstrip of obeisance to the emperor’.5

The two doorjambs of the Gate of All Nations at the top of the stairway are faced with the figures of the winged bull, bearded and crowned. Over the gate is another bas-relief of the winged god Ahuramazda. The level of the Apadana audience chamber was raised above that of the rest of the platform. There Ahuramazda is also protecting the Throne of the Great King. It was in this hall that Darius and his successors would have received the homage of the representatives of the subject peoples and the tribute which they brought.

Bas-reliefs on the Great Stairway at Persepolis showing subject peoples of the Persian Empire bearing gifts to the Great King.

It is not possible adequately to understand any great Persian building project without including the gardens surrounding the buildings. These were always of great importance as they were both places of relaxation and demonstrations of wealth and power. The Persian word for garden, paradiso, actually means an enclosed space and this has given rise to the word ‘paradise’. This also later became associated with a whole complex of buildings and gardens. It therefore represented an integrated townscape proclaiming both the splendour and the power of the Great King. This holistic Persian concept was later taken up by the other peoples who were influenced by them.

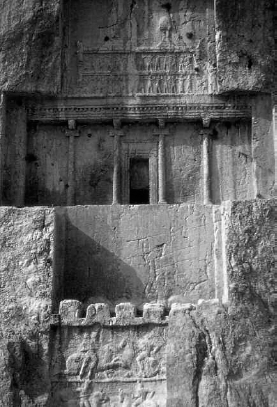

The building work at Persepolis begun by Darius was later continued by his son and grandson, Xerxes and Artaxerxes. The whole area around the capital became part of an extended sacred region for the Persians but Pasargadae retained its special position as the site of the tomb of Cyrus the Great and so of veneration for the founder of the imperial dynasty. The two were close enough to be linked both as twin symbols of the Empire and as justifications for its existence. It was in Pasargadae rather than Persepolis that the elaborate coronation ceremonies of the Great Kings were conducted. However, other royal tombs were located in Persepolis or nearby. The tombs of the successors of Darius I, including Artaxerxes II and III, are on the hill immediately overlooking the city. Some 10 kilometres to the north of Persepolis is Naqsh-i Rustam where the tombs of Darius and other successors were carved out of the rock face. On the tomb of Darius there is again an inscription justifying the world dominance of Persia. It includes the following :

Darius the King says: Ahuramazda, when he saw the earth disturbed, after that bestowed it on me; made me king. I am the King … Ahuramazda bore me aid until I did what has to be done … Me may Ahuramazda preserve from harm, and my house and this country … I am the friend of right. I am not the friend of wrong … He who does harm, he according to the harm so I punish.6

This constitutes one of the first clear statements of imperialism. Thus within this small area the Great Kings were crowned, buried and the record of their achievements was recorded in the rock.

Hicks saw Persepolis as having been ‘a gigantic living monument – a conspicuous demonstration of the Persians’ rise from rude nomads to world masters, a colossally immodest salute to their own glory’.7 It was certainly perhaps the most ambitious building project ever undertaken up to that time.

The Tomb of Darius the Great at Naqsh-i Rustam near Pasargadae. |

|

The Greeks were the only significant people the Persians failed to add to their empire. Their cause was championed by the Macedonians, whose aristocracy was highly Hellenized, and this military people were to be the downfall of the Persian Empire. In 335 BC Alexander of Macedon (Alexander the Great) attacked the Persians and defeated them. The last Achaemenid king, Darius III was killed by his bodyguards and in 331 Alexander was himself proclaimed ‘King of Kings’. He reached Persepolis in 330 BC and, as a demonstration of his victory and his contempt for the Persians, set it on fire. The city was reduced to ruins and was never used as a capital again. It had been the symbol of an empire that was always alien to the Greeks and Alexander had other plans for his new empire. He endeavoured to Hellenize the conquered lands and planted cities, modelled on the Greek polis, across them. These cities, among them many ‘Alexandrias’, were key to the process of Hellenization.8 Immediately to the east of Persepolis he established the polis of Gulashkerd, which was one of many in the historic Persian lands. Alexander intended the capital of his new empire to be at or near to Babylon, but he died there in 323 at the age of 36, well before his empire could be consolidated. Greek cities were established as far east as Afghanistan and Central Asia but Hellenization was patchy and many of these cities soon lost their Greek identity, merging into their oriental surroundings. Alexander’s only real legacy in this respect was Alexandria in Egypt which, although a splendid city that for a time became the centre of the Greek world, was never the centre of an empire.9

The Persian King Shapur I accepting the surrender of the Roman emperor Valerian; rock relief near Naqsh-i Rustam.

After the Hellenistic period and a Parthian interlude, the Persians resumed their imperial power and the Sassanian dynasty was established in AD 224. The first king of this second Persian Empire was Ardashir I, himself from Fars, a fact he used to claim legitimacy for his dynasty as successor to the Achaemenid. His own successor was Shapur I, who resumed the style ‘ShahanShah’ and adding the title ‘of Iran and non-Iran’. Although the capital of this new empire was Ecbatana on the route to Mesopotamia, the ‘sacred lands’ around Pasargadae and Persepolis retained their significance. Here are found the tombs of the Sassanian kings and rock carvings of events in Persian history dating from this period.

The main external confrontation of this second Persian Empire was with the Romans who were by this time bent on extending their power eastwards from the Mediterranean into the Middle East. The Persian-Roman confrontation was to last for many centuries and dominated the foreign policies of both empires. One of the most noteworthy of the carvings at Naqsh-i Rustam dating from this period depicts the triumph of the Persians over the Romans. Shapur I, on horseback, is seen receiving the surrender of the Roman emperor Valerian who had been captured in battle in AD 260. The humbled emperor is on his knees before the ShahanShah. While this second Persian Empire did not have the triumphant success of the first, it certainly proved a match for Rome.

The Persepolis capital region continued to retain its significance until the fall of the Persian Empire to the forces of Islam in 651. Nine years earlier the Arabs had swept through the ruins of the old capital and many of the carvings with human figures were defaced. They were deemed to be un-Islamic as was the old Zoroastrian religion. Persepolis soon disappeared beneath the dust and sand of the semi-desert and the main centres of Islamic power were located elsewhere.

While Persepolis remained a legendary capital, evidence of its existence was lost in the sand for many centuries. It was rediscovered by travellers in the eighteenth century and excavated by archaeologists in modern times. In the 1970s it was to have one more moment of quasi-imperial glory when Reza Shah Pahlavi used it as the backdrop for a great – and final – celebration of his country’s dynastic heritage.