From Karakorum to Shakhrisabz: Centres of Power of the Imperial Nomads

The great empires and their imperial cities which have so far been examined were all basically regional and centred mainly on the Mediterranean and in the Middle East. Both Persia and Rome may have thought of themselves as being ‘world’ empires, but their worlds actually consisted of fairly limited areas of the globe. Most of the original creators of these empires were nomadic tribes who migrated from far poorer areas in search of a better life. The Arabs came from the desert regions to the south, while the Medes, Persians and Turks came from the steppes, the great temperate grasslands, of Central Asia. Their conquests of sedentary indigenous peoples then resulted in the establishment of powerful imperial states. The steppe peoples were also engaged in similar conquests in south and east Asia and, like those of the Mediterranean and Middle East, the empires resulting from this were powerful but also of an essentially regional character.

Many attempts had been made to bring peace to the Central Asian steppes by attempting to unite their warlike peoples, but until the thirteenth century none of these were successful. In the thirteenth century one of these peoples, the Mongols, was at last successful in defeating the others and the extent of their conquests resulted in the rapid creation of an enormous imperial state. Unlike earlier conquests, this was in Central Asia itself and eventually it became by far the largest empire to have existed anywhere up to that time. In view of this vastness, it could with some justification, more than any previous empire, be considered a ‘world’ empire.

The whole process was begun by Yesugai, the leader of the Borjigid tribe. Following his murder by the Tatars, a rival people, his efforts were taken up by his son Temuchin.1 Such was Temuchin’s success that in 1206 he was proclaimed ‘Genghis Khan’, the universal khan, at a kuriltai, a great assembly of the Mongol chieftains, which took place on the Onon river in eastern Mongolia. The new Genghis Khan then embarked on a series of conquests which were to take the Mongols across Asia from Europe to China and southwards into the Middle East.

The Mongols were a pastoral nomadic people whose origins lay deep in the heart of Central Asia. Their homelands were south of Lake Baikal around the headwaters of the Kerulen and Onon rivers, which flow eastwards into the basin of the Amur river. Life was hard in these poorer areas of the steppe grasslands. The reasons for their successful and dramatic expansion have been variously explained. Like others before them they were attempting to bring peace to a lawless region but they were also in search of better lands and in so doing became aware of the far richer life led by other tribes on the steppes and, more importantly, by the sedentary peoples around its fringes. This was made all the more obvious to them by the trade routes across Asia from China to the western lands, bearing riches they could barely have dreamed of. Most famous of these routes was the ‘Silk Road’ between the old Chinese capital of Sian and Constantinople. Linking the two greatest cities of West and East, this carried not just silk but an enormous variety of rare and costly products between Europe and Asia. In reality this ‘road’ consisted of a number of different routes across Asia, the northernmost of which passed close to the Mongol lands. At this time China, the power that had historically controlled much of Central Asia, was ruled by the Song dynasty which had concentrated its efforts on the improvement of the Han lands, so-called ‘China proper’, and had retreated from the peripheral regions that China had formerly occupied and in which it had usually enforced some kind of order. This Chinese retreat from their wider sphere of influence had added considerably to the lawlessness endured by these areas by the twelfth century. Genghis Khan himself had experienced this in his younger days and had spent much of his childhood in hiding. This was clearly a powerful motive for his desire to bring peace to the steppes. In the first instance, he proposed to do this by securing the dominance of his own people over the territory of what is now Mongolia. The Mongols were also influenced by the Uighurs, an advanced Turkic people who had formerly occupied these lands. What the Mongols learned from them would certainly have added considerably to their ability to secure a position of dominance over the surrounding peoples.

While Genghis Khan accomplished this with little difficulty, the whole project set the Mongols against other peoples living around the edges of the conquered areas. As a result, the khan came to believe that the best solution to this was to attack and defeat them, bringing them into the ever larger territories controlled – and so pacified – by his regime. According to the Secret History of the Mongols, a written record purporting to be from around this time, Genghis expressed the belief that, ‘To bring peace you must have war! … When you have killed your enemy all is quiet all around. But I have not yet killed my enemy … And the other half of the world is still not under my heel.’2 Given the nature of Central Asia, there was no natural or easily defined boundary to expansion and the Mongol conquests continued across the steppes, defeating one ‘enemy’ after another. As they moved, Genghis Khan and his horsemen were finding out about hitherto unknown places well away from the Mongol heartlands. They knew much about China, within whose sphere of influence they had been in the past, but the rest was largely unknown to them. The Secret History also talks of uniting ‘the two halves of the world’ and in doing this the great khan explored as far as the Russian lands in the west and the fringes of India and the Middle East to the south.

However, since China was the foreign land that they knew best, it was decided at another kuriltai that this should be the next country to be dealt with. The first to face the Mongol onslaught was the state of Northern Chin which, as the Sung dynasty declined, had gained power over the northern part of the country. By 1215 the Mongols had occupied much of its territory and established a military base in the Chin stronghold of Ta-tu. This was on, or very close to, the site of the city which was later to become Beijing. Genghis Khan was killed in 1227 while campaigning on this eastern front. His exact burial place still remains unknown.3

He was succeeded by his third son, Ogedei (1229–41), a thoughtful and careful man who was more administrator than warrior, which was why he was chosen by his father over the older brothers who took more after himself. Such a man was exactly what was needed at this time. However, although he concentrated on attempting to create an administrative framework for the enormous empire, Ogedei continued the expansion largely because by this time the conquest had gained its own momentum and because there were still many enemies who resented the great power which the Mongols had gained in so short a time. Further advances were made in northern China but the most important event in Ogedei’s reign was the attack on Kievan Rus and the subjugation of Kiev in 1237. The fall of Rus’ produced great geopolitical changes in the Russian lands, leading to the rise of Moscow and Muscovite Russia. The Mongols also moved southwards to Persia and there established a khanate under the rule of the Ilkhanids, another branch of the Chinghizid ruling family. This destabilized the whole Middle East and contributed to the weakening of the Baghdad Caliphate and eventually the rise of the Turks to a position of dominance in Islam. The great outpouring of the Mongols from Central Asia therefore had a profound effect on empires and empire building throughout the Middle East and Europe.

However, despite all this frenetic activity, Ogedei’s priority was to give the empire, which was still in the course of formation, a coherent administrative structure. In order to do this he grasped the necessity for this nomadic people to have a fixed centre of power, a capital city, in the manner of the sedentary societies. This was, of course, something quite new to the Mongols who were constantly on the move and had never possessed fixed settlements of any sort. In the days of Genghis Khan the centre of power was where the khan happened to be at any time, and this was most often with his army. However, the Mongol homelands were the place to which the army always returned to recuperate after any campaign and this was where the kuriltais were held. These assemblies were called whenever major policy decisions had to be taken and, most importantly, on the death of the khan and the necessity to agree on his successor. Although the former great khan could express a wish as to who he wanted his successor to be, the Mongol ruling family, the Chinghizids, had an elective khanate. Usually the kuriltais were summoned to take place in the Mongol heartland of the Onon-Kerulen region on the slopes of the Burkhan Kaldun, the holy mountain. Initially the meeting places for these great gatherings gained the role of peripatetic capitals and they certainly had the decision-making function of a capital city. However, for the purposes of running the expanding empire, peripatetic capitals were not adequate and, in any case, this region was judged to be too remote. Genghis Khan on his return from his conquests normally pitched his tents, the Royal Ger, well to the west in the valley of the Orkhon river. This was part of the Selenge river system which flowed northwards into Lake Baikal. It provided far easier communications than the lands to the east, together with good grassland for the animals, always of the greatest importance for these pastoral nomads. In view of the increasing size of the Mongol army, the importance of adequate fodder became ever greater.

Thus even in the time of Genghis Khan a certain stabilization of the centre of power was beginning to take place and Ogedei continued with this. Soon after his accession to the throne, he began the construction of a capital city in the Orkhon valley very close to the place that Genghis had chosen for his Royal Ger. The new capital was named Karakorum, a Turkish word meaning the black stronghold. This provides another clue to the choice of location. The new capital was built close to an earlier capital which had belonged to the Turkish Uighurs who had established themselves in these lands in the middle of the eighth century. They were also a nomadic people but they had become sedentarized and went on to found a large and impressive state, the Orkhon Empire. Their capital was Ordu Balik, later known as Kara Balghashan, and the archaeological evidence shows it to have been a powerful stronghold. The Uighurs were among the first sedentarized nomads in Central Asia and they developed high levels of workmanship, including building and metal working. The achievements of the Mongols and their superiority over the other steppe peoples owed much to what they learnt from the Uighurs. These people also created their own script and this was something else which was adopted by the Mongols. This was the script used in most Mongol texts, including the Secret History. The advantages of having a fixed centre of power was perhaps the most important thing they learned from the Uighurs. They may even have thought of themselves as being heirs to the Orkhon Empire and they certainly moved rapidly to take over what had been its core region.

The walls of Karakorum were built in 1235 and by that time much other work had already been carried out. Much of what we know about what it might have been like comes from travellers who visited it during the time of the khans. Most of these came as ambassadors from European courts such as those of the pope and the Holy Roman Emperor. Famous among them were the Franciscan friars John of Plano Carpini, who visited the city in the 1240s, and William of Rubruck, who was there at around the same time. Both wrote about what they had seen, as did another traveller, Benedict the Pole, who travelled with his amanuensis, Simon of St Quentin. From these travellers we learn of the construction of walls and other building projects, most important among them the palace of the khan itself. We learn also that there were a number of religious buildings including Buddhist temples and Christian churches. The Mongols seem to have had great tolerance of most religions, and there was little desire to impose their own, something which was very rare among imperial peoples. Their own religion was a form of nature worship, widely practised throughout Central Asia at this time. At the centre of this was Tengri, the sky, a god-like presence which was the heart of their ideas of the universe. Their intermediaries with nature were the priests, the shamans, who were of great importance in Mongol life. They were called in to deal with evil spirits and to pray for rain or whatever weather the Mongols most needed at any given time.4 Tengri also gave the orders for the great conquests and it was always necessary to secure the active support of the god in order to ensure success.

Plano Carpini was in Karakorum at the time of the coronation of Ogedei’s successor, his son Guyuk (1246–8). This seems to have been a magnificent affair, the main ceremonies of which took place not in the capital itself in but in the Royal Ger just outside the walls. Although by then the Mongols had their one and only purpose-built city, they clearly preferred the old nomadic gers and used them whenever they could. The Royal Ger was closer to the hearts of the Mongols than the Royal Palace ever could be. Plano Carpini reports that during the ceremony homage was paid to the new great khan by members of the Chinghizid family and others of the Mongol aristocracy.

Today virtually nothing is left of Karakorum, even less than the remains of the much earlier Uighur stronghold of Karabalgas not far away. Russian archaeologists have dug the site of Karakorum and produced plans of what they think its layout may have been. These show the site of the palace of the khan, the treasury and the private quarters. They also reveal what is believed to be the site of the Great Ger retained by the khan within the precincts of the palace. If this is really the case, then the Royal Ger, formerly at some distance, must have been brought in to become part of the whole complex. In this way the old nomadic culture represented by the Ger, together with the new sedentary life represented by the palace, became fused into one over the years.

Ruins of the old Uighur stronghold of Karabalgas.

The reports tell us that the palace was itself of considerable splendour and that travellers were highly impressed on first catching sight of it. This is, of course, exactly what the khans intended. William of Rubruck describes it as being ‘like a church, with a middle nave and two side aisles’.5 There was always much gold and silver on display. The throne of the great khan was of gold and had been made by the Russian goldsmith Cosmas. It was raised on a plinth and there the khan would sit in state on ceremonial occasions. Among the most important of these ceremonies was the bearing of tribute by the subject peoples. In the manner of other great rulers, the khan would have wished the subject peoples to be impressed by his power and one of the principal functions of Karakorum, like Persepolis built by an earlier nomadic people, was to ensure that this was achieved.

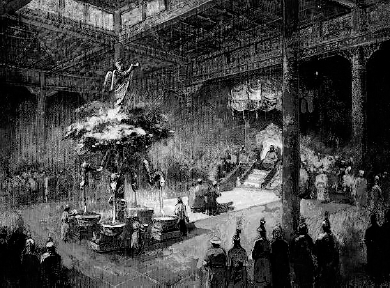

Another amazing feature in the centre of the great hall was a silver tree for the purpose of keeping the various beverages which were consumed most liberally by the Mongols. William of Rubruck describes this as follows:

Master William of Paris has made for him [the khan] a large silver tree at the foot of which are four silver lions each having a pipe and belching forth white mares’ milk. Inside the trunk four pipes lead up to the top of the tree. One of these pipes pours out wine, another caracosmos, that is the refined milk of mares, another bowl which is a honey drink and another rice mead, which is called terracina … At the very top he fashioned an angel holding a trumpet … The tree has branches, leaves and fruits of silver around which were four golden lions from whose jaws flowed wine, mead, fermented mare’s, milk and arak.6

A nice touch was that when the angel blew its trumpet it was time for the supplies of drink to be replenished. The Mongol artist Purevsukh has produced an imaginative recreation of what the whole amazing scene may have looked like. Such was the splendour with which the khans intended to impress their visitors and demonstrate the wealth and power of their empire.

By the middle of the thirteenth century the empire had reached a gigantic size and the exercise of control from the centre was becoming ever more difficult. Autonomous khanates were being established, most notably in Russia, the so-called ‘Golden Horde’, and in Persia. These khans were invariably members of the Chinghizid family and were subordinate to the great khan in Karakorum, but this subordination became ever more nominal after the reign of Guyuk. However, Mongolia itself remained the heart of the empire and it was there that the kuriltais continued to take place during which the overall strategy of the empire was discussed. However, the centre of the empire which Genghis had seen as unifying the two halves of the world was looking increasingly towards its eastern half. Even when the Chinese under the Song had retreated to their own Han heartland, the Mongols had always been subject to their influence. Although they had originally been highly influenced by the Uighurs, after attaining their great empire it was towards the Chinese civilization that they looked for further guidance. Genghis Khan had himself begun the move towards China and was influenced by the Chinese sage Chang Chun, who began to guide his ideas of empire. In the administration of the growing territories, Ogedei turned to Chinese mandarins. This privileged and highly educated class had been running the Chinese empire for centuries and Ogedei increasingly came to find them of great value. The Mongols needed their expertise and their new wealth meant that they were able to pay for it. It seems therefore that it was the combination of what they learned from the old Uighur steppe people together with the expertise they found in China that gave the nomadic Mongol tribes the ability to create an empire which was far larger and more impressive than any that had existed up to then.

The Main Hall of the Palace of the Great Khan at Karakorum, with the ‘Silver Tree’ in the centre.

Following the death of Guyuk there were disputes over the succession, and the imperial line moved to descendants of Tolui, the fourth son of Genghis Khan. The disputes came to centre on two sons, Qubilai (Kublai) and Ariq-böke, who represented very different views of how the empire should proceed. While Qubilai was in favour of continuing to concentrate on China, Ariq-böke believed, like his grandfather, that the centre of the empire should remain in Mongolia and that too much emphasis on China would result in the softening of the Mongols. It was Qubilai who eventually ascended the throne as great khan, although Mongolia remained for a long time in the hands of those who had been supporters of the views of Ariq-böke. In 1270 the Southern Song dynasty came to an end and the whole empire fell into the hands of the Mongols. This was the greatest prize of all and it largely determined the orientation of the empire from then on. During his years in China, Qubilai had been greatly influenced by the country and came increasingly under its spell. He was essentially an easterner seeing the Mongols as being part of the greater Chinese sphere which they had now come themselves to dominate.

Qubilai then took the most important geopolitical decision since Genghis Khan began his conquests – to move the capital of his empire eastwards to China. He decided that the location of this would be the old stronghold of Ta-tu, which had been the principal military base chosen by Genghis. This had the twin advantages of being in a strategic position for exercising control over China to the south and having good communications with Mongolia to the north. This facilitated ease of commerce between the two and enabled essentials from the steppes, above all cattle and horses, to be brought to China with relative ease. It was also congenial for the Mongols, since it had a climate as close as anywhere in China to that of Mongolia. The wet and humid conditions of the south did not suit them at all and they always felt alien to that part of the country.

In Ta-tu, Qubilai embarked on the construction of his new capital city which, although originally intended to be the capital of the whole Mongol Empire, became increasingly the capital of China alone. By doing this Qubilai made his empire ever more Chinese and as such heir to the Song and earlier dynasties. The Mongols replaced the Song with their own dynasty, the Yuan, and, following the Chinese custom, Qubilai gave himself the Chinese dynastic name of Yuan Zhi. By this time the Chinese influence was very strong, and the mandarins were made much use of in the administration of the Yuan empire. The building of the new capital also owed much to the skills of Chinese architects and craftsmen.

In 1272 the new capital was officially named Ta-tu, ‘the great capital’, but it seems doubtful whether most people would have used this name. Marco Polo, who visited it soon afterwards, called it Khanibalu which was his version of Khanbaliq, Turkish for City of the Khan. Once more, even in China itself, some of the old Turkish influence must have lingered. The city was built on a strict geometrical plan, quite different from the higgledy-piggledy of Karakorum. This was obviously also something learned from the Chinese and earlier Chinese capitals, such as Chengdu, which had been built in this way. Marco Polo emphasized that if one stood by the gate at one end of the city it was possible to look right through to the other end, a fact which clearly impressed the traveller. Running through the city was the river Kao-liang Ho which was dammed to form two large lakes. Besides beauty and tranquillity at the heart of the empire, these also supplied fish and helped the city’s water supply. Marco Polo described the whole plan as being like a chessboard, having a number of walls, one inside the other, with the palace of the Yuan emperor in the middle.7

At that time this palace was the residence of Qubilai and as such was the heart of the power of the empire. Ceremonial took place in the Great Hall which Marco Polo describes as being painted in all sorts of vivid colours and ornamented with carved dragons, figures of warriors and representations of battles. The roof was also gilded and had colourful paintings. In the centre of this Great Hall was what he called a ‘contrivance’, which seems to have borne a striking resemblance to the silver tree in Karakorum:

In the middle of the hall where the Great Khan holds the banquet, stands a beautiful contrivance, very large and richly decorated, made like a square coffer and cunningly wrought with beautiful gilt and sculptures of animals. In the middle it is hollow, and in it stands a great vessel of pure gold, holding as much as a large cask; it is full of wine. All around this vessel … there are smaller ones … in one there is mare’s milk, in another camel’s milk, and so on.8

These ‘milks’ were actually alcoholic and it seems that many of the old habits and customs of the steppe nomads had been transferred to the magnificence of the new Yuan capital. The ceremonial as witnessed by travellers to Khanbaliq appeared in many ways to replicate on an even grander scale what took place in Karakorum.

Nevertheless, despite all this wealth and splendour, it soon came to be widely felt among the Mongols that living in China was debilitating to those very qualities which had enabled them to get there in the first place. Ariq-böke may have been defeated by his brother but his ideas had survived. Genghis Khan himself would have agreed with these when he set out his ideas of how the empire should be governed. His plan was that the Mongols should use the knowledge and skills of the Chinese and other subject peoples to fulfil those functions which they were unable to fulfil and to produce those things they could not produce. In this way, they should use Chinese expertise whenever possible and necessary. But the Mongols themselves should always preserve their own culture. In order to do this they should continue to live in the steppe lands and maintain their pastoral nomadic lifestyle. They should also continue to rear an ample supply of horses and other livestock and bring up the next generation of young warriors to be well versed in steppe ways and warfare.9

By moving into China, his grandson had ignored this advice. Qubilai, himself a great warrior in the Mongol tradition, had become increasingly seduced by the ease and luxury that the conquered country had to offer. Nevertheless, the Mongols still took every opportunity to return to the steppes to ride their horses and enjoy the old lifestyle. Qubilai had a summer capital built at Chang-du to which he and the court retreated in the summer when it became unbearably hot in Ta-tu. This was the Xanadu of Coleridge’s poem where Kubla Khan did ‘a stately pleasure dome decree’.10

This city was situated close to the steppe lands lying to the northeast of the capital and to a degree replicated the physical conditions in Mongolia itself. There is little evidence of the pleasure dome or of Alph, the sacred river which, according to Coleridge, was supposed to run through it, but archaeologists have discovered evidence of a large complex of buildings and of the summer palace itself. Here it was possible for the Mongol rulers to engage in such traditional sports as archery and horsemanship and, for a time at least, to return to the traditional Mongol ways. Kuriltais remained a regular feature and some of these actually took place in Chang-du, but most of them were still in Mongolia itself, usually in the Onon-Kerulen heartland.

In Mongolia the Mongols had been nature worshippers and the old shamanistic religion, focusing on Tengri, was central to their beliefs. However, apart from this, the religion which appears to have had the greatest appeal was Buddhism and there were a number of Buddhist temples in Karakorum. Qubilai Khan, being inclined towards all things Chinese, appears to have taken readily to Buddhism which by this time had become an important religion in China. As part of the whole Ta-tu project, a great temple complex was constructed on the northern flank of the city. This was the Miao Ying Temple and it included, among other things, a large lamasery dedicated to ‘Greatness, Longevity, Everlasting Peace and Tranquillity’. These were sentiments which Genghis Khan, at least after his conquests had been completed, would certainly have endorsed. In the centre of the temple was a magnificent pagoda which at the time must have been one of the most impressive structures in the city. Completed in 1279 and known as the White Pagoda, it stands to this day as evidence of the importance of Buddhism to the Yuan. The design of the pagoda is that of an alms bowl and its splendid interior contains many treasures including an effigy of the enthroned Buddha and other Buddhist deities. This pagoda was the largest to be constructed anywhere in China during the Yuan period. The khan himself worshipped in this pagoda. The magnificence of the Miao Ying Temple complex must certainly have rivalled that of the palace itself and demonstrated the importance of Buddhism to the Mongols during the Yuan period. Although never a theocracy, Buddhism was a demonstration of the Chinese character of the Yuan, and their adoption of a religion which was so widespread in China served to give added legitimacy to the dynasty.

One of the motives of Genghis Khan as he built up his empire had been to secure control over the trade routes crossing Central Asia, and this the Mongols succeeded in doing. Since their conquests produced peace in the steppes, the trade routes became far safer than they had ever been. This Pax Mongolica greatly stimulated trade between West and East and the ‘Silk Road’ thrived during this period.

While the location of the Yuan capital made it quite accessible to this Central Asian communication system, the city also became the focus of a comprehensive network of roads across China. These could be used by travellers and merchants, but their main purpose was to enable the khan, his army and his emissaries to reach all parts of the country as speedily as possible. This enabled the Mongols to keep control of an increasingly restless Chinese population for the best part of a century.

One of the most spectacular projects in the improvement of the transport network was the rebuilding of the Grand Canal which by this time had fallen into disuse. It had originally been constructed during the Sui dynasty (581–618) with the aim of connecting the basins of the two great rivers Yangtse and Huang He. As a result of this, the two independent axes of China and its civilization were linked together for the first time. Under the Mongols this canal was extended northwards from Hangchow, the old capital of the Southern Song, as far as the Yuan capital. The prolific and diverse produce of the south, notably tea, silk, cotton and spices, and, most important of all, rice, was transported more cheaply and with greater ease to the capital. This added greatly to the wealth of the Yuan and to the commercial importance of Khanbaliq itself, since much of what was then taken westwards on the Silk Road was also brought in the same way.

Despite the influence which China had on them, the Mongols remained quite separate from the Chinese population they ruled. They never really became fully part of China in the way that other, even foreign, dynasties had eventually done. The Mongols always had one eye on the steppe lands, their true home, and this led to their being regarded as outsiders in the Middle Kingdom. They always ‘ruled from the saddle’ and to the end they ruled as conquerors. This contrasted starkly with the Song, their immediate predecessors, who had been the most peaceful dynasty in Chinese history. This marked contrast between the two dynasties made the Chinese even less willing to accept the Mongols as their overlords. Even during the reign of Qubilai, Marco Polo reported on the fear of rebellion which made the Mongols reluctant to allow large numbers of Chinese to live in their capital. As the Yuan weakened in the middle of the fourteenth century there was a succession of revolts against the current incumbent of the throne and Karakorum also played some part in this destabilization. The chronicles of Ibn Batuta report how the khan was away in the steppes for this reason when the Arab traveller paid a visit to the capital.

In the 1340s there was a successful Chinese revolt against the Yuan and this had its origins, like so many other Chinese revolts, in the Yangtse valley of central China. By this time the Mongols had certainly become debilitated and, disliking the south of China, they were eventually defeated by this peasant army and forced to retreat northwards. In 1368 Toghon Temur, the last Yuan emperor of China, was forced to flee and he returned to the old capital, Karakorum. Officially it was announced that this move was a strategic one and the khan was assembling new forces in order to deal more effectively with the rebels. But this was never to be and the khan died in Karakorum two years later. For a time his Yuan successors continued the fiction that they were still the emperors of China, and this went on until 1388 when the last of the Yuan dynasty, Togus Temur, was murdered in the old capital. After barely two centuries, the great Mongol imperial venture came to an end in the city which had been built to commemorate its triumphant beginnings. However, by this time much had changed in Central Asia and a new centre of power had arisen in the west.

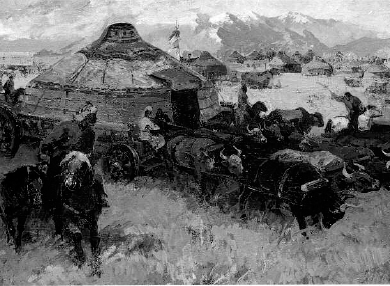

The great khans had built capitals in Karakorum and Ta-tu/Khanbaliq. In both, the splendid buildings were potent demonstrations of their power. Yet in Karakorum it was in the Royal Ger that the khans clearly felt more at home, and when in China the desire to return to the steppe life always produced a certain uneasiness. Perhaps the most potent symbol of Mongol power was really the Royal Gerlug, a ger on wheels which was carried across the steppes by horses or oxen. Purevsukh produced an artist’s impression of how this might have looked as it was travelling across the Central Asian steppe. It was the nomadic lifestyle of these people that engendered their unsurpassed martial qualities in the first place. Despite the splendour of the capitals they built, this ger on wheels was most evocative of the way in which this steppe people had created an empire extending across Eurasia from Europe to China. It had linked the ‘Two Worlds’ in a way that had never been done before. Yet in the end, despite the immense wealth and economic power which it gave to the Mongols, it was China that eventually destroyed them.

The Royal Ger on wheels; this ger was the real centre of power in the Mongol Empire during the great period of conquests.

In 1370, when news of the last Yuan emperor’s death reached the western regions of Central Asia, a warlord of the region proclaimed himself to be the successor to Genghis Khan and so to the Chinghizid dynasty. He was Timur Lenk, the Emir of Transoxania.11 Timur was a member of the Turkish Barlas clan who originally came from near Fez, now known as Shakhrisabz, then a small settlement to the south of Samarkand. Ambitious for himself and his clan, Timur had attained power as a young man by defeating the Chinghizid ruler of Transoxania. Claiming to be of mixed Turkish-Mongolian descent, he sought to find links to the Chinghizid family itself. After the proclamation of 1370 his stated aim became the revival of the great Mongolian empire which had completely disintegrated. By 1380 he had established control over the whole of the Chaghatai khanate and went on to use this as a base for the further expansion of his domains. In his conquests he displayed great cruelty to those he regarded as his enemies, and usually this included any who had the temerity to stand up against him. Although a cultured man with a love of Persian art and literature, and enjoying nothing more than having discussions with other educated men, he retained this cruel streak throughout his life.

In 1388 he attacked and defeated the Golden Horde, forcing them to flee northwards. There they became an easy target for the growing power of Muscovite Russia, which was soon able to begin the process of freeing itself from the hated ‘Tatar Yoke’. By now Timur had gained control of a large territory covering much of the western part of Central Asia but he did not feel confident enough of his credentials to take the title of khan. Rather he preferred to install a puppet khan of the Chinghizid family to be the nominal ruler of his expanding domains. However, he married a princess of the Chinghizid line and from then on he always referred to himself as ‘Gurgan’, meaning the son-in-law.

Timur’s capital and centre of power was Samarkand which he had taken in 1366. As the ancient city of Maracanda it dated back to the time of the Achaemenid dynasty and had been one of the most important trading centres on the Silk Road. Timur always returned to this city after his conquests to rest and prepare for his next campaign. During these interludes he began to embellish the city with many fine buildings, including mosques and madrasas. He lavished wealth and resources on the city, founding academies and libraries, with the intention of making it into a great centre of the arts and learning. The Spanish ambassador Ruy González de Clavijo tells us that ‘Samarkand … was the first of all the cities that he had conquered and the one that he had since ennobled above all others, by his buildings making it the treasure house of his conquests’.12

At the centre of the city was his highly fortified stronghold, the Gok Sarai – the Blue Palace – around which were laid out beautiful parks and gardens. After his visit in 1404 Clavijo observed that Samarkand was a town set in the midst of a forest in which there were gardens and running water, fruit trees, olive groves and aqueducts.13 One of Timur’s favourite gardens was the Baghi Dilkusha, the Garden of Heart’s Delight, which had been laid out to commemorate his marriage to Tukal-khanum, the daughter of the khan. Babur, writing over a century later, was of the opinion that the magnificent summer palace in the middle of it was ‘a building of imperial dimensions’.14 Everything about it was calculated to dazzle the visitor. The largest and most splendid of the mosques was the Cathedral Mosque built in Timur’s later years. This has been described in glowing terms as being of surpassing grandeur with pillars, arches, much marble and gilt doors. The traveller Yazdi considered it to be a building of perfect beauty and in Marozzi’s opinion it was ‘the apotheosis of Timur’s architectural creation’.15 Like Baghdad before it, Samarkand was above all a city of culture. At the heart of the empire, which had been won with much blood and destruction, lay this oasis of tranquillity, this ‘Rome of the east’ built with the spoils taken from the rest of the vast empire. In creating this gem, Timur laid the foundations of what was to be the great age of the Timurid khanate during the following century, when Samarkand was its glittering capital.

However, Timur also needed a capital that would reflect his great power and military achievements. This reflected the hard side of his nature in which he saw himself as ‘emperor of the world’ rather than the softer side in which he was the patron of cultural and intellectual attainments. With this in mind, he embarked on the building of another capital which was very different in character from Samarkand. For this he chose Shakhrisabz, in the territory of the Barlas clan. The new city was adjacent to the old settlement and centred on the Ak Sarai, the White Palace, the building of which commenced around 1385. This was the largest building ever built by Timur and its sheer size amazed and over-awed all those who saw it. Clavijo described in some detail how it looked in 1404. On approaching it, the first things to be seen were the huge twin entrance towers rising 200 ft from the ground and flanking a grand entrance arch 130 ft high. From there a courtyard led to a series of chambers which extended straight to the hall at the heart of the palace. This was the magnificent domed reception hall where Timur received ambassadors and other distinguished visitors. ‘The walls are panelled with gold and blue tiles, and the ceiling is entirely of gold work’, reported Clavijo. It was there that visitors first met ‘the Terror of the World’, who also styled himself ‘the Shadow of Allah on Earth’, a title which was written in Arabic above the entrance. At such receptions he would be seated on a splendid golden throne raised above the floor level of the hall. However, in contrast to all this splendour, it is reported that he himself was usually dressed quite simply in a plain gown and had little decoration on his person.

The scale of the palace was tremendous and was clearly intended for the specific purpose of impressing visitors and making them aware that they were at the court of a great and powerful king. Here more than anywhere was to be seen the truth of Timur’s assertion: ‘Let he who doubts our power look upon our buildings.’ At the other end of the great avenue leading from Ak Sarai, Timur began the construction of a mosque which was on an equally gigantic scale. This was the Kok Gumbaz mosque, and its size and location fittingly demonstrated that this was the other, although less evident, pillar on which Timur’s empire was founded.

While Samarkand, his great love, was first and foremost intended as a display of the civilization of his empire, Shakhrisabz, on the other hand, was intended as a demonstration of his overwhelming power. This and many other buildings were still under construction when Timur set off on his final military expedition. We hear of ‘feverish construction’ in Samarkand at this time and this contrasted markedly with the destruction which the conqueror left elsewhere. According to Marozzi, ‘Timur threw himself into the glorification of his capital with all the furious energy of war.’16 By the early fifteenth century, Timur’s empire stretched from its Central Asian core into Persia, Mesopotamia, the Caucasus and Afghanistan. He had defeated the Golden Horde, the Chaghatai khanate and, most significantly, the Ottoman Empire. This emerging power, which was soon to dominate Islam, clearly struck terror into the hearts of the Europeans of the time. Timur joined the list of fearsome eastern conquerors who incarnated that ‘danger from the east’ which had become an entrenched belief in the European mind. The sixteenth-century English playwright Christopher Marlowe, who called Timur ‘Tamburlaine’, presents a picture both of his power and his destructiveness. In his play Tamburlaine the Great the Ottoman emperor, Bajazeth (Bayazit I), is captured and displayed in a cage so that all can see his humiliation. The formidable power which had already crossed into the Balkans and conquered its people had been itself defeated by a far more fearsome warrior. The fear this engendered is expressed vividly by Marlowe:

The god of war resigns his room to me

Meaning to make me general of the world;

Jove viewing me in arms, looks pale and wan,

Fearing my power should pull him from his throne.

Tamburlaine the Great, Part One, Act V, Scene 1

Nevertheless, the more creative side of Timur is also acknowledged by Marlowe, who sees this as having been used to promote his glory. The conqueror boasts:

Then shall my native city Samarcanda …

Be famous through the furthest continents;

For there my palace royal shall be plac’d,

Whose shining turrets shall dismay the heavens

And cast the fame of Ilion’s tower to hell

Tamburlaine the Great, Part Two, Act IV, Scene 3

Marlowe calls Timur a ‘Scythian Shepherd’, so going along with the myth of the close association between his empire and that of Genghis Khan’s nomads. However, this was never really the case. The Barlas clan had become more urban than rural and Timur always sought solace in the beauties of Samarkand rather than in a ger on the steppes as preferred by Genghis Khan. Here we have a clear case of a sedentary people attempting to take over the empire of pastoral nomads and justifying it by creating their own myth. There would certainly have been many pastoral nomads from the steppes recruited into Timur’s army but its leadership was firmly of urban and sedentary origins.

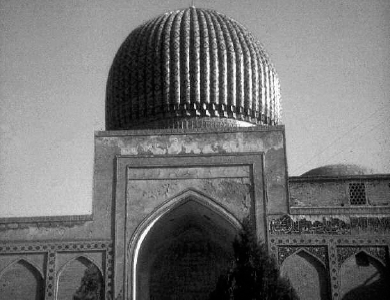

The one major part of the old Mongol Empire which had not been conquered by Timur was China. In 1405 the conqueror decided that this was to be his next and last conquest and he spent that summer assembling a formidable force which set forth eastwards from Samarkand in the autumn. Timur intended to conquer China as Qubilai Khan had done a century and a half earlier. However, the old warrior was now 69 years old and had been in poor health for some time. On the border of northern China the army ran into ferocious winter weather which held it up for weeks. Timur’s health deteriorated in the appalling conditions and he died there in January 1406. This put an end to the attempted conquest of China. His body was brought back to Samarkand where he was buried in the Gur Emir mausoleum built by his successor. The inscription on his tomb reads, ‘Here lies the illustrious and merciful Lord Timur … Conqueror of the World.’ Illustrious he may have been but he was certainly not merciful and his empire, while enormous by European or Middle Eastern standards, was only a fraction of the size of that of his alleged ancestor, Genghis Khan.

Perhaps it is in the splendour of his capitals that one can see the most marked difference between Timur and the earlier conqueror. Genghis Khan was always happier in his ger and he thought of a fixed capital as being a Chinese idea which had to be reluctantly accepted. Timur, on the other hand, saw both his capitals as being the centres of his empire and statements of its ultimate purpose. Geoffrey Moorhouse pointed out that while Genghis Khan had laid waste to Samarkand and to many other cities, Samarkand in particular was Timur’s greatest pleasure. ‘Marlowe’s “Scourge of God and terror of the world”’, as Moorhouse put it, ‘never failed to send back treasure and skilled craftsmen from his conquests, with one end in view; to make Samarkand worthier than ever of its long renown: not only Mirror of the World, but garden of souls and Fourth Paradise as well. He had a creative streak which was lacking in Genghis Khan or his heirs.’17

The tomb of Timur Lenk (Tamerlane) in Samarkand.

Nevertheless, the fear of the eastern conqueror, so vividly expressed by Marlowe, continued to influence European perceptions of Asia. It was seen as a place of barbarism and violence more than of any real cultural or intellectual attainment. Yet this was very far from being true of Timur. Samarkand had already become in his lifetime one of the great centres of science, learning and the arts. However, Shakhrisabz was designed to present quite a different image, which was the one with which Europeans of the time had become far more familiar.

Following Timur’s death in 1406 the period of Central Asian imperial conquest came to an end. It was exactly 200 years since Temuchin had been proclaimed Genghis Khan at the great kuriltai of 1206 and during this time Central Asia had been home to the largest and most fearsome empires on the globe. The size of these great empires was never to be repeated and from then on Central Asia changed its role to a place of conquered people rather than of conquerors. This was not just a matter of warlords and dynasties but was the result of important underlying geopolitical changes. Following the death of Timur the great land routes across Eurasia soon lost their importance. Even during his lifetime they had been in decline and his fearsome reputation was already beginning to deter traders from venturing across his domains. The Pax Mongolica, which had for so long ensured the safety of merchants and travellers, came to an end and the political divisions and strife which had preceded it again came to characterize the area.

In addition to this, the peripheral peoples were themselves becoming stronger and more powerful and were seeking other ways to ensure the safety of their growing commerce. These were soon provided by the new sea routes which were pioneered during the fifteenth century. Little more than a decade after Timur’s death the Portuguese Prince Henry the Navigator began the great maritime explorations which were to change the world communications system for good. The death of Timur was thus momentous since it saw not only the collapse of a great Asiatic empire but also the end of an age. The ‘Chinghizid’ age, which had been most symbolized by the so-called Silk Road, came to an end and the ‘Columbian’ age was about to begin. However, the immediate legacy of Timur was not what might have been expected. It was the legacy of his civilization rather than his power which was to be most in evidence during the following century.

Registan Square in Samarkand, which Lord Curzon considered to be the most beautiful square in the world.

Timur was succeeded by his son Shah Rukh who, together with his grandson Ulugh Beg, presided over a golden age of achievement in Central Asia. This Timurid age spanned architecture, science, painting, astronomy and many other fields. It was at this time that perhaps the most magnificent addition to Samarkand, the Registan Square, was completed. The British statesman Lord Curzon, while journeying across Asia in the late nineteenth century, expressed the opinion that this was the most beautiful square in the world. Ulugh Beg was more comfortable as an astronomer than as a ruler and he constructed a huge observatory on a hill overlooking Samarkand. The astronomers of Samarkand went on to make significant advances in astronomical knowledge. The Samarkand region also produced many scientists and scholars at this time who went on to make important contributions in the wider Islamic world. This changed the whole picture of a region which had been at the heart of one of the largest and most ruthless of empires. It was the legacy of the Timur of Samarkand which now went on to define the region for the following century, while the legacy of the Timur of Shakhrisabz, ‘the once luminous jewel of an ever-expanding empire’, as Marozzi put it, died with the great conqueror in the snows of China.18

Statue of Ulugh Beg, grandson of Timur Lenk, outside the observatory which he built in Samarkand. The ‘Timurid’ dynasty produced some of the greatest Islamic art and science. |

|

While Samarkand went on to become one of the greatest and most renowned cities in Central Asia, Shakhrisabz soon declined into insignificance. By the twentieth century the Ak Sarai had deteriorated into a colossal ruin and little remained except its vast size to indicate what it had once been. While ‘Look on our buildings’ may have been Timur’s comment on his power, few of those built to demonstrate his power have actually survived.

In Karakorum, the old heart of the Mongol Empire, great changes were also taking place. Following the murder of Togus Temur, the last of the Yuan, in the city in 1388, Mongolia soon broke up into two halves. The eastern Mongols, the Khalkha, continued to be ruled by a branch of the Chinghizids, while the western Mongols, the Oirats, broke away and established a separate state. In the early sixteenth century Altan Khan, a Khalkha leader, using Karakorum as his power base, endeavoured to reunite the Mongols and by the middle of the century he had become the acknowledged ruler of the whole country. There was again prosperity thanks to trade with Central Asia and China. In 1575 came a visit by Sonam Gyatso, an eminent Buddhist lama from Tibet. He soon had a profound effect on Altan Khan who, as a result, converted to Tibetan Gelugpa (Yellow Hat) Buddhism. Buddhism had, of course, been present in Mongolia since the time of Genghis Khan and was strong at the court of his grandson Qubilai. However, after the return of the last Yuan emperor there was little sign of Buddhist influence remaining. Altan Khan became so impressed with his guest that he proclaimed Sonam Gyatso to be the ‘Dalai Lama’, the Universal Lama, and after his death his successors were declared to be his reincarnations. Mass conversion to Buddhism soon took place and Mongolia became a deeply Buddhist country, this time looking to Tibet for its spiritual inspiration. However, Sonam Gyatso’s successors eventually decided to return to Tibet, taking the title of Dalai Lama with them. This left the Mongols bereft of the very reincarnation which Altan Khan had proclaimed and it was decided that Mongolia must have its own separate reincarnation. This reincarnation was given the title of khutuktu. He was believed to be the ‘Living Buddha’ and immediately became and remained the central figure of Mongolian Buddhism.

After his conversion, Altan Khan began the construction of a massive lamasery, Erdene Zuu, in Karakorum. Stones and other materials from the old city were used in its construction. It was surrounded by massive walls which contained over 100 stupas, dome-shaped Buddhist memorial shrines. The lamasery included living quarters for the lamas together with temples and secular buildings for administration. The temples were filled with statues of the Buddha and major figures in Tibetan Buddhism. They were eclectic in their architectural style, displaying Chinese, Tibetan and Mongolian influences. It is said that at its maximum size over 10,000 lamas lived in it. Karakorum now became the residence of both the khan and the khutuktu. A theocratic state was established in which Buddhism played a major role and the close religious links with Tibet were retained. In the great courtyard at the centre of the monastery was the Royal Ger of the khan and this was also the place where kuriltais took place. The tombs of Altan Khan and other Khalkha nobles were within the walls of this lamasery. In this way, Karakorum resumed for a time its old position as capital, but now it was the capital of a far smaller theocratic state in which the Buddha had replaced Tengri.

In 1691 at a kuriltai that took place in Inner Mongolia, the Mongolian nobles made a formal submission to accept the hegemony of the Ming dynasty. After nearly 700 years of Mongolian independence, during which the largest empires the world had ever seen had risen and fallen, the Chinese were once more back in control.

Karakorum remained the religious centre and the residence of the khutuktu until the nineteenth century when he transferred his capital to Urga, now renamed Ulaan Baatar. This was on the newly opened routeway from Russia to China via Mongolia and so in a far more convenient location than Karakorum. After 500 years the centre of power in the country had moved back eastwards, closer to the old Mongol heartlands.

While the imperial cities of Karakorum and Shakhrisabz both fell into ruins, the fate of Ta-tu, the second Mongol capital, was to be rather different. While much of the old Mongol city disappeared, it soon became the site of the building of yet another imperial capital which was to prove far more enduring than either of the others had been.