Power over East Asia: The Forbidden City and the Middle Kingdom

The fall of the Yuan dynasty had been brought about by a successful rebellion against Mongol rule that had its origins in the middle Yangtze region of central China. It was a peasant revolt against the appalling conditions of life under the Yuan who, still possessing the psychology of pastoral nomads, always despised the peasantry. The revolt was led by Zhu Yuanzhang, a man of humble origins who soon proved himself a capable leader. Zhu proceeded to establish a new dynasty which, unlike its predecessor, was Han Chinese. To this he gave the name Ming, meaning bright, and Zhu himself took the imperial title of Hong Wu.

During the rebellion Nanjing had been Zhu’s headquarters and as the new emperor he decided that this city in the heart of China should become his dynastic capital. It had always been an important centre of power in the Yangtze region and had been favoured by indigenous as opposed to foreign dynasties. In any case, the Ming emperor considered Ta-tu/Khanbaliq to have been far too much identified with the hated rule of the Mongols.

During his 30-year reign (1368–98) Zhu returned to the traditional systems which had been either ignored or abandoned by the Yuan. As part of this the old Chinese class system was revived and the mandarins were reinstated to their prime position in government. The lot of the peasantry, which had been dire under the Mongols, soon greatly improved. There was also a revived interest in the south of China and in opening up trade with the east Asian maritime world. Despite their defeat, the Mongols were still considered a danger and the stated aim of the Yuan, now back in Karakorum, was to collect together sufficient force to reconquer China. In view of this the Ming continued to keep large forces in the north and among the generals in command was the emperor’s own son, Zhu Di.

Since the heir to the throne had predeceased his father, on the death of Hong Wu in 1398 the successor and second Ming emperor was his grandson, Zhu Yunwen. This young man proved to be an ineffective ruler and he was deposed in 1402 by his uncle Zhu Di who then ascended the imperial throne as the third Ming emperor, taking the title of Yong Le. A man of great strength and ability, but quite ruthless and brutal, he came to be known as ‘Black Dragon’. Until then he had spent much of his life on the northern frontier fighting the Mongols and other tribes in this dangerous and turbulent region.

On becoming emperor, Yong Le made the surprising decision to return the capital back north to the old Yuan capital. He did this despite the fact that the ruling house was firmly based in the Yangtze area, from whence it had always drawn its support. There had also been considerable emphasis under Hong Wu on China’s southern and maritime connections which had, for understandable reasons, been largely ignored by the Yuan.

However, the move to the north took place in 1417 and the building of a new imperial palace began. Three years later the capital was formally returned to Khanbaliq which was renamed Beijing, the northern capital. By this time the old Mongol city was mostly in ruins and a completely new city was rising in its place. For the Chinese, moving the nation’s capital to a different location involved more than just an adjustment to changed geopolitical circumstances. The site and situation of the capital had since the earliest times been governed by the geomantic principles contained in feng shui, a form of geomancy. The capital had ideally to be located at the ‘pivot of the four quarters’, the point at which the emperor was in closest contact with the realms above and below the earth. These always had to be borne in mind when planning a new city and the necessity to face in the right direction and to take into account the nature of the local topography were paramount. The legend of a holy man well versed in the principles of feng shui who strongly influenced the decisions of Yong Le helped give the necessary celestial approval for what was being done.

This decision by a southern dynasty to return the capital to the north has been considered by some to be inexplicable. The most plausible explanation appears to be that the new Ming emperor had been a military man and had spent most of his adult life around the northern frontiers. As a result he had grown to feel more at home in this area. However, in addition to this personal motive, a powerful geopolitical reason for the move, and for the particular choice of site, may also have been the perceived need to reinforce the power of the north as protection in the direction from which the greatest dangers in Chinese history had usually come. The new Ming northern capital was just to the south of the Great Wall which had been originally built in the time of the Qin dynasty but which had fallen into disuse, for obvious reasons, during the Mongol period. A priority was now the rebuilding and reinforcement of the Wall, together with the strengthening of the whole system of northern defences. The new Beijing was thus a ‘forward’ capital in the sense used by Cornish, and its location was linked to the overall defence of the country.1

Nevertheless, Yong Le was as aware as the first Ming emperor had been of the importance of the country’s south and its maritime connections. This was clearly demonstrated by the new emperor’s other major decision to equip a grand fleet of impressive ships under Grand Admiral Zheng He to explore the lands to the south and west of China and to forge links with them. Although these expeditions were largely discontinued after the death of Yong Le, there was a final one as late as 1433. After that there was a surprising reversal in policy and the whole great enterprise was wound up.

It would seem that as a result of the move to the north, continental thinking had taken over and even under this indigenous southern dynasty the country had resumed its northern orientation. There were still those who yearned for a return of the capital to Nanjing, and on the death of Yong Le one last attempt was made to do this. However, by the 1440s the Ming northern capital was so well established that there could be no question of any further change taking place. In any case, by then a new city of surpassing magnificence was growing up among the ruins of the old Yuan capital and this was clearly intended to be a powerful demonstration of both Ming power and of the dynasty’s intentions.

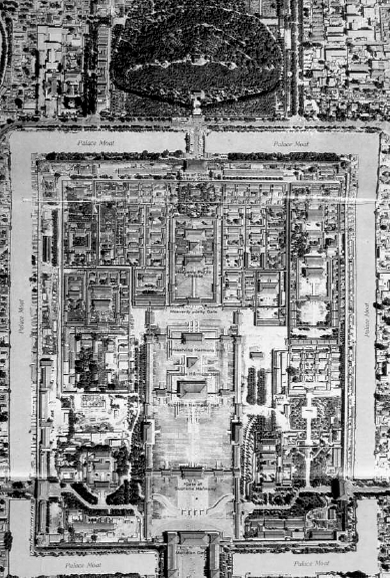

The new city which sprang up on and near the ruins of the old capital was in fact made up of four quite distinct quarters, all closely linked within a series of powerful walls. In the north was the ‘Inner City’, later known as the ‘Tartar City’, and in the south was the ‘Chinese’ or ‘Outer City’. Inside the area covered by the Inner City was the imperial city incorporating some of the beautiful lakes which had been originally made for Khanbaliq. In the heart of this Imperial City was the Forbidden City. This was ‘forbidden’ in that only the imperial family and the court and retainers were allowed to live there. Apart from those of the imperial family, the only males allowed were the palace eunuchs. These were the ‘servants’ of the emperor in the widest sense, some of them, like those of the Byzantines and Ottomans in Constantinople, eventually rising to the highest positions in the state.

Since the Forbidden City was intended to be the centre of Ming power it contained the major buildings directly associated with this power. Nevertheless, there were some important buildings outside it, notably the examination halls and a number of temples, the most important of these being the Temple of Heaven.

It has been said that the Ming capital represented the final stage in the development of traditional Chinese architecture and certainly the ideas which went into it were very similar to those of the earlier capitals. Not one of those, however, had been so clearly built to be a magnificent display of power. The nearest was perhaps Chang’an, the centre of power of the Sui and Tang dynasties, which was close to the first Chinese capital, Xianyang. This city was built on a geometrical pattern surrounded by gigantic protective walls. However, within the walls were palaces and gardens clearly intended more for the pleasure of the emperor, the empress, the harem and the court than for the display of power. The opulent lifestyle of the imperial family was kept well out of sight of their subjects.

In contrast to this, the Forbidden City was intended as a display of imperial power both for the Chinese people and for the foreigners who visited the capital. Most of the latter would be expected to be bringing tribute to the emperor. China was, after all, the Zhong guo, the Middle Kingdom, and it was necessary for both the Chinese people and the barbarians beyond to be kept fully aware of this fact and of its implications. As has been observed, the basic factors underlying its construction were the traditional Chinese ones enshrined in feng shui. The nature of the activities which took place within the Forbidden City, and for which it was built, also owed much to Confucian precepts which since early times had underlain the Chinese concept of government.

In the original plan, geomancy and cosmology played the major role, determining the disposition of all the major buildings. From the outset it was understood that the city would face southwards. This was the direction of the sun and in any case it always made sense for buildings to be orientated towards the maximum light. But besides these practical considerations, the sun was also seen as being the centre of the universe and the capital city had to reflect the fact that it was the seat of the emperor who ruled his domains as the sun ruled the sky. It was also essential that the precise orientation accorded with the celestial systems centred on the Pole Star. As it was the centre of the Chinese universe, the capital was therefore like the Pole Star in the sky. The emperor was considered to be the ‘Son of Heaven’ and it was his task to rule on earth as the Heavenly Being, Tien, rules in the Heavens. Tien is the Lord of Heaven and, as his son, the emperor has celestial authority bestowed on him. This son–father relationship tied the Ming into the celestial world and it was this above all that was deemed to give the dynasty its legitimacy.

The highly geometrical character of the Forbidden City was also intended to represent order as opposed to chaos. One of the principal functions of the emperor was to bring order to the country and therefore his own capital had to reflect this. In this way the capital demonstrated the contrast both with the disorder of nature and with the disorder that accompanies the lack of a firm and powerful authority.

The emperor having had the Tien Min bestowed on him is responsible for ensuring that there is peace and order throughout his lands and the achievement of this requires an overall situation of harmony. This is the harmonious linking together of all things in the empire so that they will live and work together peacefully and constructively for the good of the whole.

On earth the enforcement of this requires the use of power and its display is intended as being something to deter, and if necessary strike terror into, those who would upset the imperial state of peace and harmony. As Osvald Sirén put it, the Forbidden City was built ‘in accordance with the architectural principles and the ancient traditions of might and splendour, which have prevailed in the construction of all the great imperial palaces in China’.2 Sirén also noted that nothing could be seen as an individual creation but that everything was part of a greater whole and that symbols of imperial power were to be found everywhere. The most important of these was the dragon which was symbolic of many types and grades of power. The dragon of the emperor was always yellow and had five claws, while those of the nobility had only four. The lion was also a symbol of imperial power and was often placed in a position to guard the emperor and his palaces. In fact, everything in the Forbidden City was representative of something, none more so than numbers which were linked to mathematical principles and so to order. The number five always had a very special significance and this was because of the belief in the five elements which constituted the basis of the preservation of order. These were earth, wood, metal, fire and water and each had its particular place in the overall scheme of things. Every age was believed to be governed by one of these elements and the age possessed the virtues and also the weaknesses of that particular element.

Model showing the plan of the Forbidden City, Beijing.

Colours were also important and each had its own particular significance. An example of this is that while the name Forbidden City indicates the closed and mystical character of the place in which only the selected few were allowed to reside, the additional name of ‘Purple’ Forbidden City was a reference to the colour associated with the heavenly bodies. In this way the palace-city would proclaim the close relationship between the Lord of Heaven, who ruled above and dwelt in the ‘purple’ cluster of stars around the Pole Star, and the Son of Heaven who ruled in the Purple City below. This accorded well with the Confucian precept that ‘A virtuous ruler is like the Pole Star that keeps its place while all other stars do homage to it.’3 While its great walls protected the city from any dangers around it, the city was open to the heavens above. It was ‘the great within’, the heart of the Middle Kingdom, and from inside its walls all the important decisions concerning its government emanated.

The imperial throne in the Hall of Supreme Harmony at the heart of the Forbidden City, Beijing.

The plan of the Forbidden City was absolutely in accordance with the prime objective of displaying power. In the first instance, this was achieved by the routeway which was necessarily taken by those who visited the city on official business. They would have included imperial servants, provincial governors from distant provinces of the empire and embassies from the surrounding countries bearing tribute. On occasion there were foreigners from the barbarian lands beyond. These would all have been expected to enter through the Tiananmen Gate, the Gate of Heavenly Peace, which linked the sanctum with the Inner City around it. From there a walled avenue led to the Meridian Gate from where the emperor was displayed to his people on the great occasions of state. The emperor alone was allowed to pass through this gate which was otherwise normally kept firmly bolted. Only on the rarest occasions and for the most important of guests would it be opened; such guests included the candidate who came top in the imperial examinations. After this illustrious student had been accorded the honour of a congratulatory audience with the emperor he was allowed to leave in grand style through the Meridian Gate. Such students were then destined for the highest offices of state.

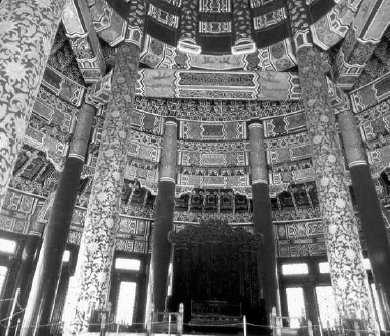

The main avenue through the Forbidden City went on past this outer Gateway to the Gate of Supreme Harmony which led to the centrepiece of the whole city, the Hall of Supreme Harmony. As has been observed, harmony was at the heart of the imperial purpose and a central function of the emperor was to preserve this at all costs. It was in this Hall that some of the most important ceremonies of state took place, including the observation of the Chinese New Year and the solstices. The Hall itself was built on the top of three terraces known as the Dragon Pavement and so raised on a great platform above the level of the other buildings of the city. At the top of the steps stood a pair of bronze tortoises which symbolized the strength of the empire and the firm foundations on which it was built. In the Hall was the Dragon Throne which was elevated on a great dais, lifting it well above the already high level of the Hall. Here the emperor would be seated in order to be the main focus of all ceremonial. The Hall was filled with symbolism including the dragon and the repetition of the number five which appears in the five colours and the five directions leading out of the Hall.

On the occasion of the great ceremonies of state the emperor was conveyed on the Chair of State covered by a yellow canopy and on his arrival heralds would cry, ‘The Lord of Ten Thousand Years approaches’. He then ascended the throne but was covered so that he could be seen only by those closest to him. The ‘Great Presence’ was too sacred to be seen by others on these ceremonial occasions. All present were then instructed to give thanks for the imperial bounty and to kowtow to the emperor.

Behind the Hall of Supreme Harmony was a succession of lesser halls which were also associated with imperial ceremonial and government. The Gate of Heavenly Purity led on to the Palace of Heavenly Purity which was another place where the emperor presided over ceremonies and also met with his ministers and the high officials of state. Most of the activities of the emperor took place within the Forbidden City but some ceremonies were also held outside it. For this purpose the great Meridian Gate was thrown open and the emperor emerged. The populace were then ordered to prostrate themselves as the emperor passed by. They were certainly never allowed to look on the sacred one. The most important of all such ceremonies took place in the splendour of the Temple of Heaven located in the Chinese or Outer City to the south. This was the most important temple in the city and it had functions analogous to those of the church of Hagia Sofia in Constantinople. At the centre of the Temple of Heaven was the great Altar of Heaven which was a magnificent circular building constructed in the fifteenth century. It was here that the emperor came to pray for good fortune for the Chinese people and, most importantly, for the harvest. However, the longest of all the ceremonies was the annual celebration of the Chinese New Year. This was also considered to commemorate the birth of the Chinese empire and was an event of the greatest significance, taking many days and involving much complicated ritual. Nearby in the complex were many other temples including the Altar of Soil and Grain and the Temple of the Imperial Ancestors. They all had their place in the endless rituals and ceremonials which took place throughout the year and at the most important of which the emperor would normally be expected to officiate.

Interior of the Temple of Heaven, Beijing.

Besides these great state occasions, the Forbidden City was intended to impress both those who saw it from outside and the privileged few who were allowed to pass through its sacred portals. The intention to link Heaven and Earth, the human and the celestial, is clearly seen from the description of one traveller many centuries later. In the early twentieth century Osbert Sitwell described how ‘The huge buildings floated upon clouds, were borne up by them … The glory that shone from the ground imparted a brilliance beyond belief to the interiors, to the great red pillars, up the length of which golden dragons clawed their way to doors and frescoed walls.’4 By that time most of the glory of the empire had passed away but the great buildings continued to impress as they had in earlier centuries.

Immediately to the north of Beijing the Ming dynasty constructed two further important symbols of their power. The first of these were the Ming tombs which covered a large area some 20 km from the capital. This vast complex contains the mausoleums of thirteen of the Ming emperors but by far the largest and most splendid of these was that of Yong Le himself. Entry to the tombs is via the Sacred Way, guarded by massive statues of animals including camels, lions, elephants and horses. A huge underground chamber containing vases, incense burners and candlesticks puts one in mind of the great subterranean tomb complex of the first emperor Qin Shi Huangdi, which contained all the preparations for the afterlife together with the terracotta army to guard him.

The second symbol was both a very real statement of Ming power and also something of practical use. This was the Great Wall which, originally dating back to the first Chinese empire, had long fallen into decay. During the Yuan period its existence had been of no relevance but now it became important again. The rebuilding instigated by Yong Le was done over a long period during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. However, by the time it was finished, the lingering threat posed by the Mongols, and later on the far more real one from Timur, had long passed and the Khalkha Mongols had once more submitted to the Chinese as their overlords. As a result it turned out after all that the newly restored Great Wall had become to all intents and purposes little more than a symbol. Its enormous size and length was both a demonstration of Ming power and a clear demarcation between the civilized Middle Kingdom and the barbarian lands beyond.

Despite its early power, by the middle of the seventeenth century the dynasty was in a much weakened state. A series of natural catastrophes such as earthquakes, floods and bad harvests had brought great suffering and had shaken the faith of the people in their rulers. In 1628 there was a severe famine in which millions died. It was coming increasingly to be believed that the dynasty had lost that Tien Min – Mandate of Heaven – which was essential for the successful governing of the Zhong guo. The last Ming emperor, Chongzhen, who came to the throne in 1627, inherited a discredited administration. In desperation he turned to the Jesuits who had been present at the imperial court for some time. This powerful religious order, which had first come to China in the wake of the Portuguese in the sixteenth century, was able to acquaint the Chinese with many of the technical advances taking place in Europe, but even they could not help a dynasty in the terminal stages of decline. All their intervention did was to cause more trouble by making even the mandarins, always suspicious of the Jesuits, begin to doubt the legitimacy of the emperor and of the Ming dynasty itself.

Beyond the Great Wall, historically always the place of greatest danger to the Chinese, there had been further menacing developments. The peoples living immediately to the north were becoming increasingly restive. These were the Manchus, the people of Manchuria, who had been historically within the Chinese sphere of influence but had usually been strong enough to maintain independence. Whenever China was weak this was seen as an opportunity by the peoples of the north. China was now showing all the signs of degenerating into chaos and the Manchu, who had been expanding their territories for some time, saw their opportunity. By the 1630s their army reached Shantung where they displayed their martial prowess and were successful in defeating a far larger Ming army. In 1644 they breached the Great Wall and soon reached the gates of Beijing. In response, the last Ming emperor called a council and proclaimed that, ‘I, feeble and of small virtue, have offended against Heaven.’5 He proceeded to remove his imperial robes and retired to the hill north of the Forbidden City where he committed suicide. The Ming dynasty, which had been so triumphant in removing the Mongols, had been forced to submit to another non-Chinese people.

Very soon afterwards the Manchu army entered Beijing and a Manchu dynasty was proclaimed. This took the name of the Qing, and the Manchu king, Aisin-Gioro Fu Lin, became its first emperor. He took the imperial title of Shun Zhi. The reign of this young man was dominated by his uncle Dorgon and it was mainly spent in consolidating Manchu power over the whole of China. It was the second Qing emperor, Kangxi (1661–1722), who set the seal on what was to be a very successful dynasty by showing himself to be deeply respectful of all aspects of Chinese culture and prepared to continue the system of imperial governance which had been developed and perfected by the Ming. First and foremost the imperial capital was to remain in Beijing and very few changes were made to it for fear that the whole system of imperial governance would come tumbling down. Qing Beijing remained essentially Ming Beijing. As Cotterell put it, the new dynasty saw that nothing was to be gained in disturbing the cosmic layout of the imperial capital ‘which had been built in the centre of the earth in order to govern the whole world’.6

The only major innovation was the building by Kangxi of the summer palace to the north of Beijing. The site chosen included hills and lakes and this magnificent natural location was used to great advantage. Kangxi wrote:

In harmony with the natural contours of the country I have built pavilions in the pine groves thereby enhancing the natural beauties of the hills … I have made water flow past the summer houses as if leading the mountain mists out of the valleys … I think of virtue.7

In this place an imperial palace, temples and other buildings constituted a magnificent retreat well away from the heat and dust of summers in the capital.

However, the Qing dynasty, like their predecessors, ruled most of the time from the Forbidden City and dutifully carried out the Ming rituals. Although Manchus, they adapted well to China and came rapidly to be looked on as virtually an indigenous dynasty. Already subjected to Chinese influences in their homeland, they were accepted easily by their new subjects. This was something the Mongols had never been able to achieve.

By the eighteenth century, large parts of the world were either under direct European political control or at least were in the sphere of the maritime powers. However, like the Ming before them, the Qing were not interested in having much to do with the ‘foreign devils’, as the Europeans were by this time known, and did all they could to keep them at arm’s length. Like the Ming, they found the Jesuits both interesting and, to a certain extent, useful, but they were certainly not prepared to accept the notion of European superiority in any way or to make any real concessions to them.

As Britain moved into its position as the leading world maritime power in the eighteenth century, the urge to forge closer relations with China became irresistible. China had been able to retain its position as a closed kingdom outside the Eurocentric global system that had been in the course of creation for two centuries. Despite the huge changes taking place around it, the Zhong guo still considered itself the centre of the world and far superior in the arts of civilization to the barbarians outside its borders. However, the Europeans were becoming ever less prepared to accept this Chinese isolation and were bent on the creation of their own maritime version of the Silk Road. Largely as a result of pressure from the East India Company, which dominated the eastern trade, in 1792 a British diplomatic mission led by Lord Macartney was dispatched to Beijing for the purpose of paving the way for the opening of diplomatic relations which would lead to trade. It was the biggest mission ever sent to China by a western power and was at first received with great courtesy and formality. An audience with the Qianlong emperor was arranged and this took place in the summer palace. However, despite many meetings with officials and the exchange of presents and platitudes, in the end the mission proved unsuccessful. Among other failings in the eyes of the Chinese, the British did not show the required degree of deference. The idea that the British would treat the Zhong guo as some kind of equal power was quite shocking to them. As the mission drew to a close, the reply of the emperor was finally delivered at a grand ceremony in the Hall of the Gate of Supreme Harmony in the Forbidden City. The emperor was not present and the imperial letter of reply to King George III was placed on the imperial throne and had to be itself kowtowed to as though the emperor were actually sitting there. In the reply, the request for an exchange of embassies was flatly refused in the most peremptory terms. The emperor referred to ‘wanton’ proposals for an ambassador to stay at ‘the Celestial Court’, something which was quite out of the question. It was firmly ruled out as being ‘not in harmony with the state system of our dynasty and so will definitely not be permitted’.8 It is significant that this final meeting took place at the Gate of Supreme Harmony and that the word ‘harmony’ was also used in the imperial letter. This was, after all, the ultimate and supreme function of the emperor and he certainly was not going to allow it to be interfered with by these dubious foreigners. For the emperor to have had anything to do with foreign devils would certainly not have accorded with the required harmony prescribed by the names of the halls of the Forbidden City itself.

However, despite this display of contempt, the reality was that China was already much weakened in both actual and relative terms. The idea of the all-powerful Zhong guo, which might still have been a reality during the rule of the Ming, became more and more unreal during that of their successors. This was soon realized by many within China itself and a few years after the Macartney Mission the conflict between the traditionalists who wished to keep the foreigners at bay and the modernizers who were prepared to allow them in had come to a head.

By the nineteenth century the material progress of the Europeans had become spectacular. Those inventions which the Jesuits had in earlier centuries displayed to the Chinese were nothing compared to what the Europeans, led by the British, now possessed. The introduction of such wonders as the railway, the telegraph and coalmining was something the modernizers saw as necessary if China was to keep up, but the traditionalists resisted them tenaciously. They believed that such things did not accord with feng shui and so would destroy the harmony so essential to the smooth and proper functioning of the celestial empire. This opposition was led by the mandarins who had always been suspicious of the Europeans and their inventions.

As custodians of Chinese culture and civilization they saw their pre-eminence at the heart of government being threatened by the Europeans. The attempt to force trade on the Chinese, later done in the most brutal and disastrous manner by the British in the Opium Wars, caused many Chinese to distrust and hate foreigners, especially the British, even more. Nevertheless, it also made them realize that these foreigners could no longer be resisted. The defensive walls of China were quite inadequate to keep out this new and all-pervasive invasion.

No Great Wall could keep out the modern world for ever and by the end of the nineteenth century the great powers had secured a number of bases in the country by various means, including the use of military force. By then they had been accorded territorial ‘concessions’ in many ports and were permitted to set up embassies in Beijing. The British had established themselves in Hong Kong as an entry point into China from the south and were using it to extend their trade. The diplomatic quarter housing the embassies in Beijing was close to the Forbidden City and so was a constant reminder to the imperial government of the much changed world situation in which the country now found itself. A century after Qianlong’s dismissive letter the outside world was closing in on the Zhong guo. At the same time the ‘harmony’ which isolation had promoted and encouraged was fast breaking down and with it the hold of the dynasty itself. After 250 years in power the Qing dynasty were losing the Mandate of Heaven but, like all dynasties before them, they were extremely reluctant to accept that the end was in sight.

The last effective Qing ruler of China was the Empress Dowager Ci-xi, daughter of a Manchu nobleman and one of the wives of Emperor Xian Feng. She was the real ruler of the country for half a century, following the death of her husband in 1861. She was able to maintain her power through intrigue and manipulation during the reigns of a succession of weak or child emperors. For most of this time rebellion was in the air, and in 1900 came the rebellion of the Society of Harmonious Fists, more popularly known as the Boxer Rebellion. The Boxers sought a return to traditional values and blamed the dynasty for allowing outsiders to gain such a hold and bring with them such things as the railway. This aroused great suspicion and was widely felt to represent the unwelcome changes being imposed on the country. In order to protect their embassies and their concessions, which were under threat of violence, the powers assembled a joint military force and intervened. Their success in breaking through Boxer resistance to reach Beijing and relieve their embassies was a clear demonstration of their power and of the weakness of China. The Empress Dowager and her court were forced to flee from Beijing and the great powers were left virtually in charge of the city. The heart of the Zhong guo was now at the feet of the foreigners and the humiliation of China was complete.

It is significant that the Empress Dowager fled to the old Qin capital, Xianyang, and for a time set up her court there. When she was at last allowed to return in 1902 her magnificent imperial procession made a detour to visit the former capitals, beginning with Chang’an, before arriving back in Beijing. The final part of her journey to the capital actually took place by rail, a clear demonstration that the modernizers had in effect won. During her final years in power, the Europeans continued to tighten their grip on the country.

The Empress Dowager and the puppet emperor Guang Xu, in whose name she ruled, both died within months of each other in 1908. The funeral of Ci-xi was the last great imperial event not only of the Qing dynasty but in the whole of Chinese history. Ci-xi’s great nephew Pu Yi ascended the dragon throne as the last emperor, taking the title of Xuan Tong. Two years later an uprising took place, centring on the middle Yangtze region, and the country was again thrown into turmoil. On 1 January 1912 a republic was proclaimed in the southern capital, Nanjing, and a month later Pu Yi abdicated the throne. The official announcement of the abdication, which came from the Forbidden City, was accompanied by the pronouncement that ‘Tien min is clear and the wishes of the people are plain.’9

With this announcement the power of Beijing, which had dominated China for most of the previous 650 years, came to an abrupt end. The new nationalist regime was firmly southern in its origins, its attitudes and its choice of capital. While the former emperor Pu Yi was allowed to go on living in Beijing for a few more years, the Forbidden City was otherwise empty and abandoned. The mystique that had surrounded it over the centuries had vanished.

Within two decades China was to face a whole generation of massive turmoil caused by the invasion by the Japanese and the subsequent Civil War. During this turbulent and divisive period in the country’s history, what was left of it was ruled from a number of capitals, mainly in the south and centre. Yet, as had been the case with the Ming centuries earlier, with the return of stability a new government would again be seduced by the lure of the north. Although it might have seemed highly unlikely in 1912, the role of Beijing as the centre of power was far from being over.