Grandeur: Louis XIV and Versailles

In the seventeenth century the principal centre of power in Europe shifted from the Mediterranean to northern Europe. This fundamental geopolitical change was marked by the Treaty of Westphalia of 1648 which ended the Thirty Years War. In 1618, at the beginning of that war, Spain was still the dominant power in Europe, but by the time it ended everything had changed. Spain had been greatly weakened and was not even a signatory to the treaty which dealt mainly with the new arrangements in post-Westphalian northern Europe. The power of the Holy Roman Empire was much curtailed and the Protestant kings and princes were accorded full recognition. In one of the treaty’s constituent parts, known as the Treaty of Münster, the United Provinces were recognized as an independent state and became the Dutch Republic. This small but dynamic country was to dominate world trade for the rest of the century.

The country which now replaced Spain as the dominant power in Europe was France. For the rest of the century this power was engaged in the entrenchment of its position and in the further enlargement of its territory by steadily moving its frontier eastwards. In 1643 Louis XIII, who had been king throughout the Thirty Years War, died and his four-year-old son, Louis XIV, ascended the French throne. The country was run by a Regency with a dominant first minister, Cardinal Mazarin. The death of Mazarin in 1661 gave Louis the opportunity to assert his authority and he was able to take full charge of the government of his country. There were many who aspired to power of the sort which Mazarin, and before him Richelieu, had enjoyed but Louis was strong willed and did not allow this to happen. A later painting of the king emphasized this by depicting him as Jupiter with the inscription ‘Le Roi gouverne par luimême’ (The King rules alone).

Louis XIV carried on a great deal of the foreign policy of his predecessors but with far greater vigour and aggression. Most of his long reign was taken up with wars in which the French frontier moved inexorably eastwards, adding large parts of the Spanish Netherlands, Franche Comté and Alsace to the king’s domains. By the closing years of the seventeenth century the area of France had increased by about a third over what it had been a century earlier. By then the country also had the largest population in Europe and had become by far the continent’s strongest military and economic power.

Louis was determined to assert both the dominant position of his country and his own position of dominance in France. In seeking to achieve his goal, he embarked early in his reign on the building of a new centre of royal power. This was symbolic of his intentions and was intended to impress all who visited it with the power of his country and the magnificence of his monarchy. Paris had been the French capital since the country had first come into being in the ninth century and the Louvre, the splendid royal palace, was at its heart. The city had developed a hold on France far greater than either Toledo or Madrid ever had on Spain. ‘The reason why Olivares failed and Richelieu succeeded’, wrote Fisher, ‘is that in France conditions were favourable to centralization whereas in Spain they were adverse. All ways in France lead to Paris. No ways in Spain lead to Madrid.’1 Besides being the capital, Paris was also a great economic and cultural centre. It was the location of the Sorbonne, one of Europe’s earliest and most prestigious universities, and became a magnet for large numbers of people seeking to avail themselves of the opportunities which a great capital afforded. These ranged from merchants and craftsmen to students from both France and the neighbouring countries.

However, like Philip II of Spain in the previous century, Louis wished to detach himself from his capital. The reasons for this were not dissimilar from those of the Spanish monarch as the city had been far too closely associated with the turbulence of the recent past. Most alarming had been the outbreak of disorder known as the Fronde which had taken place during Louis’ childhood and had resulted in the monarchy for a time being in a precarious state and even being forced to flee the capital. With such associations in mind, when he assumed power in 1661 Louis did not feel that Paris was a safe place to be. An underlying motive for the move away was therefore the necessity to find somewhere where the monarch and the royal family could be more easily protected.

Louis also had another motive which was to design a centre of power which would reflect his ambitions for France and enable him to carry them out more easily. He was an absolutist and his idea of the monarchy was that it should wield total power. This was encapsulated in the famous phrase attributed to him, ‘L’Etat, c’est moi’. He wished to be unhindered by all the other elements that make up the kaleidoscope of a nation and are inevitably present in its capital city. However, since Paris was so much the undisputed centre of the country, he did not intend to disengage himself and his government totally from this prime location.

In considering the nature of his project Louis looked to other similar examples, but in Europe at that time there were few. Philip’s monastic Escorial palace was not what he had in mind at all and he was more interested in the great city which Shah Jahan was building in Delhi at this time. News of this was brought back by travellers, notably François Bernier who submitted to Louis a detailed description of what was taking place. To what extent this actually influenced the construction of the new palace is uncertain but in some respects there are distinct similarities. The objectives of the two monarchs were, after all, very similar. However, there was another great chateau nearer home towards which Louis looked with some admiration and much envy. This was Vaux-le-Vicomte, the palace built for himself by Nicolas Fouquet, his first minister of finance. This impressive and costly project typified what Louis had in mind for himself. He felt strongly that such a grand palace should be for a king and not a minister. His resentment towards Fouquet grew both on account of the power he wielded and his display of wealth. The minister’s fall as a result of charges of financial corruption freed Louis of this overpowerful and over-grand rival. Never after that was any minister of his allowed to attain such wealth and power.

Louis chose as the site for his palace the village of Versailles, some 20 km to the southwest of Paris. Here his father Louis III had a hunting lodge and it was around this that the building of the new royal palace began in 1664. The architect Le Vau was in charge of designing the first stage which consisted of enveloping the hunting lodge in a completely new structure. Later Le Brun and Hardouin-Mansart contributed to the building and its adornments and Le Nôtre designed the spacious gardens and their surroundings.

Despite the huge numbers of workers employed, the construction of the new palace was a slow and painstaking business and it was not until 1682 that the court was able finally to move to Versailles. In so doing the king made it his new centre of power and of the government of France. By that time the palace had grown to enormous proportions with hundreds of rooms intended to accommodate the large numbers who made up the court and government. All officials, members of the government, the royal family and, of course, aristocrats were expected to reside there either permanently or at least for part of the year.

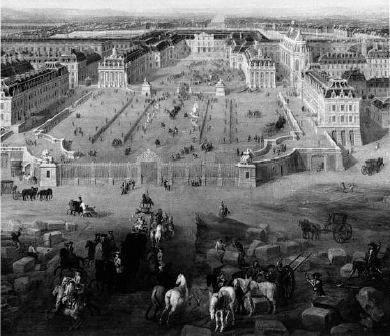

The approach to the palace was itself a highly impressive experience, as one travelled through the grid pattern of avenues on which the new town of Versailles was planned. A long avenue led to the vast expanse of the Place d’Armes around which were the Royal Mews, barracks and other official buildings. At the end of this were the great gates beyond which were the courtyard and the main entrance to the palace. The whole was built in the classical style and its awesome vastness was clearly designed to impress all who made the short journey from Paris with the power and splendour of the monarch.

In the middle of the palace was the Grand Appartement du Roi, which initially was where the king resided and was also the most important centre of government activity. It consisted of seven principal rooms, each named after one of the known planets. The plan was heliocentric and centred on the Salon d’Apolon, the Greek god most associated with the sun. It was from this that Louis came to be known as ‘le Roi-Soleil’, signifying that the king was to France what the sun was to the solar system. This was a very similar notion to that of the Chinese emperors who were proclaimed to be the ‘Sons of Heaven’ and derived their authority from this. The salon was also originally the Throne Room in the centre of which the solid silver throne of the monarch was situated. On the walls of this salon and of the other rooms in the Appartement were paintings by Le Brun of scenes of the exploits of heroic figures such as Cyrus, Alexander the Great and Augustus. Louis XIV wished to associate himself with these great historical figures, giving a clear indication to all that he saw himself in this heroic tradition. It followed from this that he saw France as an imperial state with a historic role akin to the great empires of ancient times

Parallel to the king’s apartment was the Grand Appartement de la Reine which consisted of another set of rooms decorated with similar splendour. Just as the king’s apartment was decorated with paintings of legendary heroic figures, those of the queen were decorated with the heroines of antiquity.

Some changes to the whole structure were soon needed for the addition of what was to be one of the centrepieces of the palace, the Galerie des Glaces – the Hall of Mirrors – which was designed by Hardouin-Mansart and completed in 1690. This hall was the most magnificent and highly decorated in the whole palace and was intended for the purpose of holding grand receptions and conducting state ceremonial.

While initially the Grand Appartement du Roi was used as the centre of government, as the size of the palace increased and the Salon d’Apolon ceased to be used as the Throne Room, changes were made and the centre was moved to La Chambre du Roi, the king’s bedchamber. In the centre of this was the enormous royal bed with its impressive fittings and decorations. This soon came to be regarded as the real heart of the palace and so the centre of the government of France. This might seem an extremely bizarre arrangement but it accords with the idea that the monarch was a public figure to be viewed at – almost – all times. The principal axes of the palace and the gardens radiated from this Chambre, thus symbolizing the fact that all power in France also radiated from there. It was there that the most important formal and ceremonial events associated with the monarch took place. These began in the morning with the levée, the rising of the monarch, followed by the ceremony of dressing and the partaking of breakfast, all of which were watched by a large collection of people. Beside nobles and government ministers, this also included members of the public who wished to behold their monarch and to have some contact, however brief, with him. In order to enter the presence of the monarch it was necessary to observe a certain code of dress and swords had to be worn. Otherwise members of all classes could attend this ceremonial and were invariably greeted politely by the king. In the afternoon the king would often stroll in the gardens, and these walks too soon took on the role of ceremonial. In fact, the whole palace was designed as a backdrop for the grandeur of the king and through him the grandeur of the country over which he ruled. Louis’ life became in many ways a day-long spectacle and, as Seward put it, the king ‘resembled an actor perpetually on stage’.2 According to Saint-Simon, with a calendar and a watch one could tell what the king was doing at any hour of the day.3

The Palace of Versailles in the early 18th century.

At the rear of the palace were the great gardens designed by André Le Nôtre. Highly geometrical in form, they were planned so that the whole vista could be seen at a glance. These gardens were intended to complement the chateau and to provide a suitably impressive setting for the whole project. The symmetrical layout had a central axis which followed that of the palace itself. Trees and plants were brought from far afield, including 3,000 orange trees from Italy. Water was diverted to provide sufficient for the great elongated lake at the centre and for the fountains on statues of Neptune. Supplying sufficient water for the whole vast complex proved problematic and the military engineer Vauban was called in to help rectify this. He attempted to build an aqueduct over the river Maintenan but this failed to resolve the issue and the inadequacy of the water supply remained a persistent problem for the palace and its gardens. While the taming of nature was successfully accomplished, the cooperation of nature proved more difficult to achieve. Vauban’s precept that in order to tame nature it is necessary to obey her did not fit well with the prevailing ideas at Versailles. There the concept of man dominating nature fitted much better with the idea of the monarch dominating France and France dominating Europe. The best view of the whole garden was said to be from the Chambre du Roi itself and this meant that the centre of power was complemented by a vista to match. Or in Nikolaus Pevsner’s words, ‘Nature subdued by the hand of man to serve the greatness of the King, whose bedroom was placed right in the centre of the whole composition’.4

The palace of Versailles, together with its associated lodges, gardens and grand avenues, was the greatest and most impressive building project of the era anywhere in Europe. More than one commentator has dismissed it as being little more than a monumental piece of folly by a monarch who was intoxicated by his own splendour. According to Ashley, Versailles was ‘the place he designed for his magnificence, in order to show by its adornment what a great king can do when he spares nothing to satisfy his wishes’.5

Be this as it may, it can hardly be denied that the existence of Versailles played a major role in the eventual collapse of the Bourbon dynasty. It is certainly true that it reflected Louis’ love of the luxurious and the ostentatious and the monarch enthusiastically took on the role of principal actor on this massive stage. Nevertheless, as with the other great imperial cities which have been examined, there was more to it than this. Important raisons d’état underlay Louis’ magnificent and costly project.

As the palace grew in size, it became ever more the heart of the government of France and Louis also came to see it as a way of controlling the great nobles who in the past had possessed so much power that they rivalled that of the king himself. Members of the nobility were called on to serve in the government and some were chosen to be ministers. These were referred to as the noblesse de la robe and they often became so involved with Versailles and its affairs that they left their estates to decline. Many nobles were soon bankrupt and had to be bailed out by the king, thus increasing their dependence on him. This was exactly the situation that he wanted to achieve. Versailles became the only route to preferment for the nobility and regular attendance at court was therefore essential. Even if they did not have such positions they were nevertheless required to attend the court and to live for at least part of the year in Versailles. The splendour of the court turned their heads and the rural life became ever more boring for them. La Bruyère’s assertion that ‘provincials are fools’ became generally accepted. They were drawn to Versailles like moths to a candle. When their estates suffered, living in Versailles became their only option. In many ways it became a home for great nobles who were fast losing their raison d’être. Versailles had turned into the principal instrument for the taming of the nobility. The words ‘He is never seen’ became the greatest condemnation and the nobility fell in with this with surprising readiness. They came to believe that attendance on the king in Versailles was the only thing really worth doing and that remaining on their estates was very much a second best. The nobility, said Morris, had been placed in a gilded cage from which there was no real desire to escape.

Indeed, such sentiments applied not only to the nobility but to all who had the honour to serve the king. Cardinal Richelieu, Mazarin’s predecessor, is on record as having said, ‘I should rather die than not see the King.’ Although this had been said before Louis XIV came to the throne it was very much a sentiment that came to be widely felt among the king’s subjects. The visibility of the monarch was at the heart of the whole great project.

As the nobles luxuriated in their gilded cages, the king moved to secure tighter control over his domains. He placed royal officials, the intendants, as his representatives in different regions, thereby increasing his own direct grip on the country. They were the forerunners of the prefects, and this was the beginning of the process which was to make France the most centralized country in Europe.

The sheer magnificence of the monarchy was on display at Versailles and the splendour of the palace and its grounds spoke louder than words. All who visited, and there were many, were awestruck by what they saw. Colbert, Louis’ finance minister after the fall of Fouquet, viewed the palace as being a ‘showcase’ for France. His aim was that everything, from the decor to the paintings and furniture should be French. The widespread belief of the time was that a country was stronger when it was self-sufficient and this was something that Colbert wished to bring about for France. Thus while Versailles was symbolic of the grandeur of the monarchy, it was also intended to be symbolic of the strength of France as the leading power in Europe.

The geometrical plan of the palace and the gardens also symbolized order, an order which tamed nature and imposed an organized pattern on it. Le Nôtre’s idea of the ‘jardin d’intelligence’ accorded well with the planned order which it was Louis’ aim to bring to France. This was all very much in line with the developments in science taking place in the later seventeenth century, which were transforming the way Europeans thought about the world and the role of mankind within it. What was in nature diverse and chaotic was being unified into an organized and intelligent system. Far from ‘obeying’ nature as Vauban proposed, Versailles represented the imposition of order upon what was regarded as chaos. In the same way, in the human world, what had been diverse and chaotic was now also being given order and purpose. A unified taxation system was introduced, unified laws promulgated and even a unified culture promoted. This was accomplished by means of the establishment of academies. The Académie Française, Académie des Beaux-Arts and Académie de Musique were intended to exercise control over the French cultural scene and make it part of the system designed to unify the state. This search for order was epitomized in France by the ideas of Descartes. Cartesian logic underpinned most thinking, imparting the same mathematical order to the human world as was being discovered to exist in the physical. The overall objective was to create a France which through its unity of purpose would be the centre and focus of the new emerging Europe. As it turned out, it also entailed the creation of the first of those nation-states that were to become the principal heirs to medieval Christendom. Over this ordered world presided Louis, ‘le Roi-Soleil’, shining like the sun at the heart of his own solar system.

This represented a final break with the Middle Ages and the central role for Christianity and Christendom. Spain was the last power to devote itself to the preservation of this system and in this it had failed. The European world had undergone a massive change both geopolitically and in the realm of ideas, and the France of Louis was the principal exponent of this new post-Westphalian model. While the Catholic Church was still part of the new France, like most other things within the state it was also given more national characteristics. The idea of the ‘Gallican’ church fitted more readily into a state in which all the elements were linked together in a kind of living whole. The principal representative of this view was Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, the bishop of Meaux, who believed in a balanced and tolerant Catholicism which would play its role as a component part of the French state. Bossuet drew up the ‘Four Articles’ which affirmed the independence of the French Church from that of Rome. He was an exponent of absolutism and talked of a ‘loi fondamentale’ which regarded the king as being God’s image on earth. Louis himself paid sufficient heed to the important role of the Church within the state. He had his own chapel in Versailles and attended Mass every morning. Still, in what has been called ‘the pagan paradise’, religion had lost the central position it had held in Christendom. The main purpose of Philip II’s state had been to promote Catholic values and support the Church. In Louis’ France the opposite was true. The role of the church was to play its part in supporting and strengthening the monarchy. The whole idea of a sun king, after all, was hardly a Christian one. It and the god Apollo were drawn from the beliefs of the pagan world. Louis came to be regarded, and to regard himself, as a kind of god figure. In an early address to the sovereign, the Paris parlement effused, ‘the realm’s estates pay you honour and duty as they would to a god who can be seen’.6 They referred to him as ‘Louis le Grand’ and considered that his was ‘the throne of the living God’. This all represented a massive break with the past and the beginning of that marginalization of religion that was to reach its apogee in the French Revolution. The unified and centralized state which Louis produced was also the most powerful in Europe and by the second half of the seventeenth century it had taken over from a much weakened Spain as the new centre of power on the Continent. The objective of creating a Europe united around France and subservient to it was seen as another way in which the mathematical order of the universe was being transposed to the human world.

The magnificence of Versailles, itself far more splendid than any other royal palace in Europe, symbolized this ambition. The geometrical plan of the great palace and its gardens focusing on the Chambre du Roi was akin to the geometric plan of a Europe in which France was the sun, the focus of power, around which the smaller and less powerful states revolved. This was the new – and even natural – political order replacing the old order of Christendom. However, this grand ambition was never to be fully achieved as a result of the coalition of states led by the Netherlands and England which were determined to restrain the territorial ambitions of the French monarch.

Louis XIV died in 1715 after one of the longest reigns in European history. The Treaty of Utrecht, ending the long War of Spanish Succession, had been signed two years earlier and had produced a very different order from that envisaged by Louis and his ministers. Rather than one power dominating, the new eighteenth-century Europe was to be one in which a number of rival powers sought advantage for themselves but in the end tended to balance one another out. Alliances formed among them kept aspirants for the prime position from achieving their goal. France certainly for the time being remained the most powerful of the European states but the others stubbornly refused to revolve around her alone. The sun with its satellite planets was certainly not the appropriate celestial analogy for the new Europe in the making. If there was such an analogy it was of many stars in the firmament, some bright and some less so but each maintaining its place within the whole.

Versailles remained the residence of Louis’ successors and it continued to be the heart and symbol of that unified and centralized state which was his main legacy. However, to an increasing number of French men and women it also symbolized wealth and privilege and was the focus of the discontent that grew in the country as the gap between the privileged and the underprivileged, wealth and poverty, continued to widen. The things Versailles had been intended to symbolize came under increasing scrutiny as the military and economic power of France began to wane. The need for change came to be widely felt throughout the country, except in that ‘gilded cage’ which was Versailles itself. There the parade of power and privilege went on much as before. In 1789, three-quarters of a century after the death of Louis XIV, the country erupted into revolution. The famous – or infamous – remark put into the mouth of Queen Marie Antoinette in response to the growing conditions of famine, was ‘Let them eat cake’. Whether this is true or not it is illustrative of the great chasm which had opened between a court isolated in luxury and the mass of the people in poverty.

Following the Revolution, the king and the royal family were forced to return to Paris where they were certainly confronted by the poverty and anger of the people. In 1793 both king and queen were guillotined alongside thousands of those aristocrats whom Louis XIV had made obsolete. They had nevertheless been able to retain their privileged positions and this is what sent them to the guillotine. From then on Versailles became an empty shell, its halls filled only with the memories of past greatness. For those regimes which ruled France during the nineteenth century, Paris was once more the undisputed capital.

However, the vast palace was still used occasionally for great ceremonial events. Ironically, one of the most splendid of these was the proclamation of the creation of the new German Empire after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71. While the building of Versailles had signalled the beginning of French hegemony in Europe, it was the unlikely setting for the rise of another hegemonial power. Half a century later the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in the Galerie des Glaces aimed to set the seal on yet another new European order after the First World War. With the beginning of the age of mass tourism, the palace became a magnificent museum visited by millions who marvelled at the wealth and power that had created something so incredible.

The most lasting legacy of Versailles was the creation of the highly centralized French nation-state. While the sun and its satellites had long ceased to be appropriate, the geometrical representation of France as a hexagon, its towns and cities arranged in a quasi-geometrical fashion around Paris, continued to give the idea of an order which could not and should not be interfered with. The order which had been enshrined in Versailles and its gardens became the model which modern France has continued to follow.