St Petersburg and the Imperial Vision of Peter the Great

Aquarter of a century after the transfer of the French seat of government to its new home in Versailles, on the other side of Europe another grand project with a very similar objective was getting under way. This was the foundation of the city of St Petersburg which took place in 1703. Located at the eastern end of the Gulf of Finland on the deltaic estuary of the river Neva, from the outset it was intended by its founder, Tsar Peter I, ‘the Great’, to be the new capital city of the Russian Empire.

Peter reigned from 1689 to 1725. He was therefore a slightly younger contemporary of Louis XIV of France and, like the French monarch, he had visions of greatness for his country. These, however, entailed a far more radical transformation than had ever been the intention of Louis. Although Louis built a completely new seat of government, it was very close to Paris, which had been the capital of France since the country came into existence. The basic geopolitical structure of the French state remained largely unchanged and France continued to be ruled from a seat of power at the centre of the Paris basin. Peter, however, was responsible for the complete transformation of the geopolitical structure of Russia.

Peter was the greatest modernizer in Russian history, and he saw his role as lifting his backward-looking country out of the Middle Ages into the eighteenth century. Europe was undergoing a massive transformation in virtually all fields and by the later seventeenth century this transformation was most in evidence in the countries of northwestern Europe, in particular the Netherlands and England. Peter desperately wanted Russia to be a part of this but he realized that nothing could be accomplished without massive changes. The establishment of the new capital was without doubt his most important step in bringing this about.

Although Moscow had long been a fortress in the forests of central Russia, after the fall of Kievan Rus it had been completely transformed into a magnificent capital city in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries during the reigns of Ivan III ‘the Great’, Vasili III and Ivan IV ‘the Terrible’. It was planned specifically to be the capital of Muscovite Russia – ‘Holy Russia’ – and this entailed the unity of state and Church at the heart of power. The Muscovite state saw itself as being essentially the heir to the Byzantine Empire and thus indirectly the heir to Rome itself. However, while the Roman world and its heirs had dominated Europe for the best part of 2,000 years, by the seventeenth century the principal centre of power in Europe had moved northwards and Russia had fallen well behind the new developments taking place there. Peter put this backwardness down to the fact that his country was virtually landlocked and had looked towards the east and south rather than westwards towards Europe. A further factor was the dominant role of the Orthodox Church in the affairs of the state and the continuing prevalence of ideas inherited from the now defunct Byzantine Empire. Geography and history had thus combined to make Russia a backward-looking country cut off from the mainstream of new political and scientific ideas which were increasingly dominating European thinking. Peter wanted to change all that and to open the doors of Russia to Europe. He envisaged the future of Russia as a modern European power. Peter was a ‘westerner’ but on becoming tsar he found that the ‘easterners’ were very much in control in his capital. His radical solution to this situation was to get away from them and all they represented by moving to a new capital.

Much of Peter’s thinking had its origins in his childhood experiences. Following the death of his father, Tsar Alexis, in 1676 problems arose due to the physical and mental weakness of the immediate successors Fedor and Ivan. Peter, the son by Alexis’s second wife, was marginalized by his half-sister, the Regent Sophia, and forced to live away from court in the village of Preobrazhenskoe. He was a strong and intelligent young prince and quickly learned much, especially from the foreigners in the nearby German colony. It was there that he became acquainted with what was happening in western Europe and he was especially fascinated by boats which he sailed on the nearby river. His increasing knowledge led him to the lifelong conviction that maritime power was essential if Russia was to develop. The acquisition of such power presented a huge problem for a virtually landlocked country and one which could only be solved by acquiring a more suitable coastline.

In 1689 Peter became joint tsar with his feeble-minded half-brother, Ivan. This arrangement lasted until 1696 when Ivan died and from then on Peter reigned alone. Only then was he able to begin his grand project of modernization which had been in his young mind for so long. In order to achieve this, in 1697 he embarked on a great journey to western Europe in order to see for himself the wonders which he had been told about by the foreigners he had met in his childhood. This was the ‘Grand Embassy’ and in the first instance it went to the Netherlands, regarded as the most technologically and scientifically advanced country in the world at the time. There he was able to see for himself – and actually take part in – the advances in shipbuilding, navigation, artillery and a variety of other industries and to marvel at the construction of the huge dams and water-control projects. The Anglo-Dutch king William III invited him to visit England, an offer he accepted with alacrity. There he was able to witness similar activities and to see the commercial and industrial activity taking place in the English capital. He also experienced the rich cultural, scientific and political life of the great city. Unsurprisingly, the English Parliament does not seem to have impressed the Russian autocrat and political freedom was one thing he did not desire to import into Russia. As a result of these travels, he now knew how an advanced modern country worked and it prepared him to undertake the transformation of his own country along the same lines.

There was, of course, huge opposition to the envisaged changes and this was especially the case in Moscow, the centre of the old order. In 1698 the revolt of the powerful palace guard, the streltsy, gave Peter a warning of the problems which the project of modernization would face. Seemingly this was one of the factors which finally made him determined to move the centre of government to a new capital, well away from Moscow, where he would be able to put his ideas into practice without interference. He combined this with his other great desire to open up Russia by giving the country a more satisfactory maritime frontage and ready access to the sea. This presented Peter with his first major geopolitical problem and in order to resolve it he realized that he would have to go to war. This war, when it came, was to last for most of the rest of his reign.

In the west, Russia was hemmed in by three powerful states which completely prevented access to all but the icy northern seas. In the south was the Ottoman Empire which had controlled the eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea since the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453. As the self-proclaimed successor to this empire, the Russians had always felt a powerful pull of destiny in this direction. They retained an underlying desire to liberate Constantinople and to free all Orthodox Christians from what they regarded as Islamic interlopers. However, the immense power of the Ottomans had always made this project unrealistic. In the centre was Poland, at the time a large and formidable country which itself had ambitions to unite all the Slavs around it. It was Catholic in faith and so was hostile to Orthodox Russia. Poland blocked the most direct contacts with Continental Europe by land or sea. In the north lay Sweden which in the late seventeenth century was at its most powerful and which, after the Thirty Years War, had converted the Baltic Sea into a Swedish lake.

It was to the north that Peter decided to make his principal move, since the Baltic provided the best maritime route westwards to the North Sea and to those advanced countries which he had visited. In 1700 war broke out between Russia and Sweden over a territorial dispute. This was the Great Northern War and it was to last more than two decades.

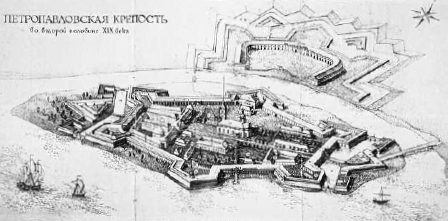

In 1702 Peter’s forces captured the Swedish stronghold of Noteborg and so secured access to the Gulf of Finland. The following year construction commenced of a Russian fortress on one of the islands in the Neva delta. This was the beginning of St Petersburg. Traditionally, the date of its foundation was 16 May 1703 and the site chosen was on the island of Ianni Saari, close to the Swedish fortress of Nyenchants. Peter talked triumphantly of planting the Russian flag on this fortress in place of that of the Swedes.1 The island was close to the northern bank of the Neva and many reasons have been given for its choice, including the more suitable terrain and the greater security afforded by this particular island. Many myths later arose, notably the one that Peter saw an eagle hovering in the sky above the island and immediately set about digging the first turf. This has resemblances to the myths associated with the choice of other sites, including Constantinople, showing that the links with old Russian beliefs and traditions were far from being entirely severed. Peter had a log cabin built nearby so that he could supervise closely, and even take part in, the work. It was a massive project and large numbers of Swedish prisoners were forced to labour on it. Since this was still very much in a war zone, the first building was a fortress which Peter named the Sancta Petropavlovsk (St Peter and Paul). It was the very first part of the construction of what was to become the new capital of Russia. From the outset, Peter seems to have made it clear that he intended his new capital to be there. In letters he used the Russian word stolitsa, meaning capital, rather than gorod, meaning town or city. It is significant that the stolitsa was first given the Dutch name of Pieterbruk and the first foreign merchant vessel which arrived in that year was Dutch. Likewise Noteborg was renamed not with a Russian but with a German name, Schlüsselberg, meaning the ‘key’ fortress. This indicated its importance for the defence of the new city. The new Russian fleet was soon to be based on another neighbouring island, renamed Kronstadt. These Dutch and German names clearly demonstrated the direction in which Peter was heading with his new Russian Empire. It seemed that becoming more European meant that it was also going to be less Russian.

It is interesting that at the time of its foundation Pieterbruk was legally still on Swedish territory and it required a considerable act of faith, and also of audacity, for Peter to begin the building of his new capital on the territory of another state which was still very powerful. However, Russia was becoming each year more confident both on land and sea. In 1709 the Swedes were defeated at the battle of Poltava and in 1714 came the decisive battle of Hangö which was Russia’s first ever naval victory. This heralded the country’s arrival on the scene as a naval power and also brought to an end the half century during which the Baltic had been a Swedish lake. In an address after the battle of Poltava, Peter asserted that ‘now with God’s help, the final stone has been laid in the foundation of St Petersburg’.2 The following year, 1710, the court finally moved away from Moscow and settled in the new capital. However, it was not until 1721, with the Northern War ending in victory for Russia, that the country’s capital was legally on Russian soil. By this time a considerable city had already arisen in the marshes and islands of the Neva delta. The Treaty of Nystadt ending the war also transferred to Russia the provinces of Karelia, Ingria, Estonia and Latvia, giving her control over the Gulf of Finland and ready access to the Baltic. The new capital was still highly peripheral to the enormous Russian Empire which stretched eastwards as far as the Pacific Ocean, leaving it dangerously vulnerable to attack. However, it was soon well protected by the forts in the Gulf of Finland, and the new acquisitions on the Baltic. Above all Russia now had a formidable navy which was based on the island of Kronstadt downstream of the capital. This build-up of power in the Baltic region represented a major geopolitical shift in the Russian Empire both from south to north and from continental to maritime.

The original St Petersburg was thus built on an island in the Neva river and was initially little more than a defensive fort, one of the many guarding the new Russian presence in the Baltic. It was designed in the Vauban style, another west European feature which displayed knowledge of the latest military engineering. Inside its massive walls there was ample room to accommodate other buildings. It was, in fact, a kind of maritime Kremlin which sheltered the combined elements of military, state and Church. In this way, despite the vigorous westernization in which Peter was engaged, the traditional Russian concentration of power within a fortress was still in evidence. Construction continued throughout the reign of Peter and into that of his successors, and western European architects were always prominent. At its centre is the Cathedral of SS Peter and Paul designed by the Swiss architect Domenico Trezzini. This was built in the European classical style hitherto unknown in Russia. The grand entrance gateway to the fort was also designed by Tressini. It is in the form of a triumphal arch with the two-headed imperial eagle prominently displayed and is topped by a bas-relief which gives thanks for Russia’s victory in the Northern War. The tomb of Peter himself, together with those of all the subsequent tsars until the revolution, was in this magnificent building. Close to the cathedral is a small building housing the skiff in which Peter sailed during his childhood. This was intended as a reminder of how the great transformation of Russia had started.

Immediately to the north of the fortress was the first part of the emerging city. Known as the St Petersburg side, it is actually on another island between two arms of the Neva. It was there that Peter’s log cabin was built. The Troitskaya Ploshad (Trinity Square), slightly to the east of it, was the first real centre of the city. On the northern side of this square stood the wooden Church of the Trinity and on the other side was a German hostelry, named rather grandly the Triumphal Hostelry of the Four Frigates. This was where Peter availed himself of ample alcoholic refreshment during respite from his labours.

However, Peter never intended the centre of the new capital to be there at all but on an adjacent island. This was Vasilievsky Island, located downstream between the Bolshaya and Malaya – Great and Little – Neva. He envisaged this as a kind of ‘Baltic Amsterdam’, possessing all the facilities for a great port and with waterways winding through it. To achieve this ambition he embarked on the construction of a canal system crossing the island. He also ordered the construction of official government buildings and houses for the army of civil servants and administrators whom he intended to bring from Moscow. One of the first buildings there was the Menshikov Palace, the residence of the governor of the city. The island, with its docks and ready access to the sea, soon became the city’s first centre of commerce. However, there were as yet no bridges and the only links to the island were by sailing boat, on which Peter insisted in preference to the more practical rowing boats. Highly dependent on the weather, these proved to be to be unreliable and often hazardous and the Vasilievsky project had to be abandoned before the end of Peter’s reign. As a result it came to be realized that the most practical place for future development would be on the mainland immediately to the south of the river. However, the eastern spit of Vasilievsky island, known as the Strelka, was soon to gain its own special character with the opening of the university in 1725, followed by a number of libraries, museums and institutes. In this way it evolved into the intellectual and cultural centre of the new capital. The island also remained the city’s commercial and financial hub, retaining its port facilities and stock exchange. In the following century, with the erection of the Rostral Columns, it became more than anywhere else representative of the capital. These two impressive columns at the eastern end of the Strelka were intended to commemorate Russian naval victories and were imitative of the Roman practice of erecting symbols of victory. The figures at the base of the columns represented the four great rivers of Russia – the Dniepr, the Don, the Volkhov and the Volga. In this way the symbols of the overwhelmingly maritime character of the city, and of Peter’s new Russia, were linked with symbols of the Russian past, so acknowledging the importance of the rivers in earlier Russian history.

Plan of the Peter and Paul Fortress, St Petersburg.

From the outset Peter wished his new stolitsa to be beautiful as well as functional. To achieve this he not only took great interest in the architecture but sent for large numbers of plants and trees to fill the new parks and gardens which he was planning. As well as being the spearhead for the new orientation of his empire, Peter saw his new city as being a ‘paradise on earth’. It was, he said, like living in Heaven. After his trials and tribulations in Moscow one can understand the emperor’s sense of liberation when he established his own capital well away from the old one. The city was thus to combine the roles of paradise and centre of a revived Russian Empire.

In the opinion of Hughes, it was far from being another ‘Third Rome’ but rather more a recreation of the ‘First Rome’ – pre-Christian, imperial and pagan.3 It certainly came to possess many features which could be termed pagan, but there were also many churches and the Christianity of Muscovite Russia was by no means abandoned. It was certainly intended to be the new Rome for Peter’s Europeanized, and powerful, Russian Empire.

Those who were forcibly transferred to work in the new capital did not by any means share Peter’s rosy image of it. Rather than being any kind of paradise, they were more likely to view it as a cold, damp, sunless and unhealthy place in which they had been forced to live under duress. For them, what were commonly referred to as ‘the unhealthy Finnish marshes’ were far from having that image of desirability which Peter sought to impart.

Whichever was the truer picture of the new capital, and its physical setting, for Peter it had one immense physical advantage over the old capital. It had maritime access and, as well as being the capital, it was also a vibrant port and the country’s main naval base. In fact, in Peter’s mind these factors were fused together in the forward thrust of his dream of a modern and European Russian Empire.

The Europeanization which Peter instigated in decrees issued from his new capital covered most aspects of Russian life. He decreed that the wearing of beards was henceforth forbidden and all the men were ordered to shave them off. Later, in the face of massive opposition to this decree, Peter compromised and introduced a beards licence. This was symbolic of the massive break with Moscow and the religious traditions of that city, since from the beginnings of Russian Orthodoxy the wearing of a beard had been a sign of saintliness. Furthermore, the introduction of European dress at court also represented a powerful symbolic break with the old culture.

Besides these externals, huge changes were made in political arrangements. A Senate was established which was given limited powers for the discussion of important issues and for lawmaking. This was, however, no parliament in the English sense and it was never allowed to interfere with the ultimate authority of Peter himself. The body remained advisory rather than legislative. The administration of the empire was divided into a new system of colleges, each of which was responsible for the handling of a particular aspect of state business. To bring Russia more closely into line with Europe, the old Russian calendar, which started from the beginning of the world, was abolished and a new European one was introduced that began on 1 January 1700. Finally, Peter himself took the Roman title of imperator in place of tsar. He ignored the Byzantine version, basileus, further emphasizing the strong message that he was modelling his new empire on Rome rather than Byzantium. Even in his view of the ancient world, Peter was looking to the west rather than the east. This alienated him all the more from the traditional Muscovite hierarchy which had looked to Constantinople rather than Rome and based itself on Byzantine rather than Roman religious and political traditions.

While the whole Russian Christian tradition had always been an Orthodox one, Peter set about its modernization by looking to western practices. He abolished the patriarchate and replaced it with a synod. The architectural style of the cathedral of SS Peter and Paul, at the centre of the great fortress bearing their name, was essentially European and this was also the style of most other churches later built in the capital. Most fundamentally, the role of the church in state affairs became more limited. The close link between Church and state, which was spectacularly symbolized in the Moscow Kremlin, was broken and the dominance of the state was asserted. While Peter professed to be Christian, his actions were increasingly driven by secular considerations. As Marc Raeff put it:

The administration ceased to play a religious role … In the place of the most pious tsar we find the sovereign emperor, wearing a European-style military uniform, residing at the western extremity of his empire, and isolated from the spiritual and religious life of his people.4

In face of all these massive changes, the ‘Old Believers’ became the centre of the fight to keep the old Russian culture alive. To them, the Petrine reforms were an abnegation of the very nature of what was to them ‘Holy Russia’. Their firm belief was that Moscow was the ‘Third Rome’ and the new capital was little more than a den of iniquity. The determination of the Old Believers to protect the culture gave rise to what Raeff termed the ‘“two nations”, two cultural universes, between which there was little, if any, exchange’.5 Raeff saw the process of westernization as having resulted in the erection of what he called a ‘great wall’ separating the political elite from the masses.

It is difficult to see how these great changes could possibly have been brought about were it not for the existence of St Petersburg, located well away from the old centre of power at the western extremity of the empire. There were indeed ‘two nations’, with two capitals. They may have been inhabiting the same territory but they were inhabiting different cultural universes. The new and the old capitals were geographical representations of this situation. The imperial vision of the old Russia was to liberate the Christian terra irredenta in the east, regain Constantinople from the Infidel and unite the whole of the Orthodox Christian world under Russian hegemony. The imperial vision of Peter’s ‘new’ Russia was quite simply to convert a still medieval country into a modern European power.

The triumph of the new secular vision was also the triumph of St Petersburg and of the power, military and naval, scientific and commercial, which Peter was able to muster around him there. It was the triumph of the modern over the medieval but it also resulted in the opening up of a divide in Russia from that time on. The common complaint that Peter was foreign to Russia was voiced by disgruntled aristocrats who allegedly asserted that ‘we don’t have a sovereign any more but a substitute German’. The idea took hold that with the active encouragement of Peter, Germans were taking over the country. Whether this was true or not in Peter’s time, it would certainly become more the case during the reigns of his immediate successors. Of course, Peter had first learned of the wonders achieved by foreigners from the Germans and later from the Dutch. This all amounted to much the same thing in the minds of the Russians, for whom ‘Germans’ and ‘foreigners’ became in many ways virtually interchangeable terms.

By the end of Peter’s reign the new capital was still far from being the magnificent city it was to become later in the eighteenth century. Many of the buildings were of wood and most of them were either on the islands or on the St Petersburg (north) side. The growing city consisted of four distinct quarters, each separated from the others by water. The fortress was at the heart of it and adjacent to this was the St Petersburg side, which had some of the earliest buildings and was the original social hub. Thirdly there was Vasilievsky Island which by then centred on the strelka and still possessed some of the most splendid buildings. However, it had become obvious that future development should now be on the mainland and the south bank was the chosen place for this.

Here in 1705 was erected what to Peter must have been by far the most important building. This was the Admiralty which was central to the whole south bank development. In 1711 further improvements were made to the building and later on in the century it was altered once more. From there radiated the major avenues leading to the south and along the banks of the Neva. Most important among them was a grand avenue, the Nevsky Prospect, which was planned to lead southeast-wards to the Alexander Nevsky monastery. From 1710–11 a house was built for Peter slightly to the north of the Admiralty at the junction of the Neva and its tributary, the Fontanka. This was designed by Trezzini and was known as the Summer Palace. Around it were laid out magnificent gardens with fountains, lakes and conservatories. Most of Peter’s architects for these projects, including Andreas Schlüter, Georg Johann Mattarnovy and Gottfried Schädel, were German, and nearby was the quarter known as the German Suburb. The German and Dutch input was decisive for the character of the new capital but a notable exception to this was that of Jean-Baptiste Alexandre Le Blond who arrived from Paris in 1716. It was he who laid out Peter’s gardens, using Versailles as the model. He also drew up the plans for the Nevsky Prospect which later in the century was to become the most splendid grand boulevard of the city. In addition he planned the building and gardens for Peter’s retreat at Peterhof on the south bank of the Neva just outside the city.

The Admiralty, St Petersburg. For Peter the Admirality would have been the true heart of his city; it is centrally located at the intersection of the major roads and avenues south of the river.

After the great emperor’s death in 1725 most of his successors throughout the eighteenth century were women, and this succession of remarkable empresses continued the work of consolidating the new capital as the accepted centre of the empire and further embellishing it with buildings in the European architectural style. These were mostly on the south bank of the river which from then on became more and more the real centre of the city.

THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SUCCESSORS OF PETER THE GREAT

1725–7 |

Catherine I, second wife of Peter the Great |

1727–30 |

Peter II, grandson of Peter the Great |

1730–40 |

Anna Ivanovna, daughter of Ivan, early co-tsar of Peter the Great |

1740–41 |

Ivan VI, great-nephew of Anna Ivanovna |

1741–62 |

Elizabeth Petrovna, daughter of Peter the Great and Catherine I |

1762 |

Peter III, grandson of Peter the Great |

1763–96 |

Catherine II, ‘the Great’, wife of Peter III. A German Princess, Sophia Augusta, she became the empress by staging a coup and deposing her husband |

The most impressive additions were made by Catherine the Great during whose reign the Russian Empire became more firmly European and more powerful than ever. It was said that when Catherine came to the throne her capital was built of wood and when she died it was built of stone.6 This might have been something of an exaggeration, but a number of catastrophic fires had shown how unsafe the old wooden buildings were. Besides this, the empress required that her capital should have more buildings of greater splendour and this was another reason for brick and stone. Catherine was said to have been the second founder of St Petersburg. However, the building of the great imperial palace, the Winter Palace, in place of Peter’s Summer Palace, had already been started as early as the reign of Anna and was continued under Elizabeth. Catherine greatly extended it and added the Hermitage which was later to become one of the great art galleries of Europe. During her reign the avenues were also built up and the quays, unstable from the outset, were strengthened and consolidated in stone. At that time the Commission of Stone Buildings which she set up did much to enhance the appearance of the city. The baroque architecture of Rastrelli’s Winter Palace gave way during Catherine’s reign to a more restrained classical style and the empress engaged new architects, notably Vallen de la Motte, Rinaldi, Cameron and Quarengi, to introduce and develop this style. It was as a result of the work of Catherine that St Petersburg attained its true classical splendour. Voltaire expressed the opinion that ‘The united magnificence of all the cities of Europe could not equal St Petersburg.’

The Winter Palace, St Petersburg. In the 18th century this became the centre of power of the Russian Empire and remained so until the Revolution.

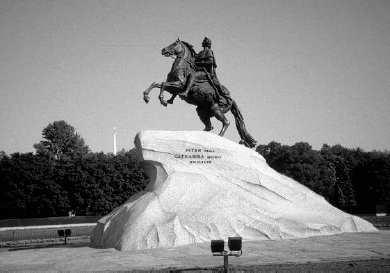

The Bronze Horseman, equestrian statue of Peter the Great by Etienne-Maurice Falconet. Commissioned by Catherine the Great to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the beginning of Peter’s reign, it was unveiled with great ceremony in 1782.

Catherine also made St Petersburg a far more desirable place for aristocrats and government officials to reside. No longer did they have to be cajoled into living there. By the end of the eighteenth century the capital had a vibrant social and cultural life and all the facilities necessary for luxurious living. The Russian upper classes came flocking to the capital both for the civilized life which was possible there and, more importantly, because without their presence in the capital they had little chance of promotion in government service. All this had echoes of Louis XIV’s Versailles, which the aristocrats were encouraged to believe was the only place to live.

To link herself to Peter the Great and to further consolidate both her own legitimacy and that of St Petersburg itself, Catherine commissioned what has become one of the capital’s most impressive symbols, the great bronze statue of Peter which was erected close to the Admiralty in 1782 to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the coronation of the city’s founder. The Bronze Horseman by Falconet show Peter in a dramatic pose. The Latin inscription on the great granite base refers to Peter as ‘Imperator’. Catherine, a German princess before she became empress, was completely European in her attitudes and she was quick to assert that the Russian Empire was a European rather than an Asiatic power.

Yet, it was not until after her reign that the centre of the city really achieved its present architectural form. The Palace Square, with its triumphal arch and the General Staff Building, was not completed until 1820, during the reign of Alexander I, and the new Admiralty building, with its distinctive twisting steeple, was not completed until 1823. By then St Petersburg had became the most perfect example of a European classical city. It symbolized a Russian Empire which was very much part of Europe and its literature, art and music were integrated into the wider European cultural scene. The transformation of Russia, begun a century earlier by Peter the Great, was complete and by the end of the Napoleonic Wars the orientation of the country was firmly to the west.

Arnold Toynbee summed up the truly radical nature of the move of the capital to the Gulf of Finland. As a result, he asserted,

Moscow was temporarily deprived of her prerogative as a result of her rulers’ decision to open their doors to the West … Moscow was compelled, for more than two hundred years, to see her empire governed from a capital which was not only given a new name but was planted on virgin soil on a far-distant site … The transfer of the capital of the Russian empire by Peter the Great from Moscow in the heart of Holy Russia to Saint Petersburg on the banks of the Neva, within a stone’s throw of the Baltic, is comparable to Nicator’s choice in its cultural and geographical aspects.7 In this case, as in that, the seat of government of a landlocked empire was planted at the corner of the empire’s domain in order to provide the capital with easy access by the sea to the sources of an alien civilization which the imperial government was eager to introduce into its dominions. In its political aspect, however, Peter’s act was much more audacious than Nicator’s; for, in seeking to supplant Moscow by Saint Petersburg, Peter was ignoring the feelings of the Orthodox Christian ruling element in Muscovy with a brusqueness reminiscent of the revolutionary acts of Julius Caesar.8

The very existence of St Petersburg transformed Russia. From continental it had become maritime and from Eastern it had become Western. It was this which made Russia one of the acknowledged great powers of nineteenth-century Europe. In fact, during that century it transcended Europe and became a global power. The other major nineteenth-century global power was Great Britain, and Russia became for a time Britain’s main rival on the world scene.9 Together they became the dominant powers of the age, strongly influencing events in both Europe and the rest of the world. It would have been very difficult to envisage such a situation a century earlier and it would certainly have been impossible without the move to St Petersburg and all that followed from this.

However, the existence of St Petersburg continued fundamentally to divide Russia. Moscow, the old capital, retained its position as the acknowledged heart of old Russia. Here was the centre of the Russian Orthodox Church and here the emperors continued to be crowned as tsars in the Uspensky Cathedral in the age-old manner. In this city the heart of traditional and unchanging Russia continued to beat. The old ways of life in the rural areas surrounding it, together with their traditional industries, the kustari, continued to flourish. This was all very different from the life of the capital. There the clothing was European, the preferred speech of the aristocracy was French, and a class of artists, writers and intellectuals had emerged who thought in an essentially European way.

Besides all this, the capital had become the site of much new industrial development. The industries set up there were very much like those of western Europe and as a result a class of industrial workers had come into being who were very different from the crafts people who worked in the kustari industries around Moscow. Those involved in the industrial life of the old capital were still closely associated with the land and remained essentially semi-urbanized peasants.

St Petersburg had no such large surrounding rural population and industrial workers moved there from other parts of Russia. They soon lost their association with the land and became, in Marxian terms, an industrial proletariat. This development was fraught with problems for the future. By the late nineteenth century new political ideas were in the air which advocated change to the way the autocratic country was run and the establishment of a democracy on the European model. Even more ominously for the existing system, there were new ideas about changing the nature of the economy so as to make it more equitable. The most significant of these ideas were those of the German Karl Marx who became ever more influential in the early twentieth century.

In 1904 revolution broke out in the capital and the autocracy was shaken to its foundations. St Petersburg, which Peter had deemed to be the safest place for his own revolution two centuries earlier, had now become the least safe place for his twentieth-century successors. Emperor Nicholas II conceded the establishment of a Duma (parliament) but it had little real power. The rumblings of revolution were in the air. Little more than a decade later the October Revolution took place. It was uncompromisingly Marxist and resulted in the overthrow of the Romanov dynasty and the transformation of the enormous Russian Empire into the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. It is ironic that the last act to take place in the capital of Imperial Russia was the overthrow of that dynasty which had originally established it. It is equally ironic that after the fall of the regime the capital was forsaken by the revolutionaries and the centre of power was transferred back to the old pre-Petrine capital.

St Petersburg had come into existence shortly after Versailles and was, in many ways, modelled on the magnificence of Louis XIV’s creation. Both had a crucial role in the radical transformation of the states of which they were the capitals. This resulted in considerable modernization and it is significant that both the French and Russian monarchies were subsequently overthrown by revolutions. Both revolutions owed much to the modernization which had prepared the ground for further change. While in each case modernization had centred on the purpose-built capitals, after the revolutions neither Versailles nor St Petersburg were able to regain the central role they had once possessed. Despite the glitter of Versailles, Paris was regarded as the ‘natural’ capital of France while, to many Russians, Moscow had always been the heart of the ‘real’ Russia. The post-revolutionary regimes later used these cities to fulfil their own particular purposes.

In the early twentieth century, around the same time that revolutionary activity was rocking the Russian Empire, its great global rival, the British Empire, was also in the process of change. This was considerably less revolutionary in character and, in the first instance at least, was intended to prolong its existence. In particular, a major change was being planned for India, that most strategically vital of British imperial possessions. This considerably altered the geopolitical character of British India and brought it closer to that of earlier empires in the subcontinent.