Once again Lucas found himself sitting in front of his computer as those around him left for the day. In the cubicle behind his, he heard someone call out, “You’re not making this a habit, are you, Lucas? You’ll make us all look bad!”

“No, I’m heading home in a few more minutes,” he answered absently, staring at the remaining fifty or so emails in his inbox. He knew he needed to wade through them and respond. His new boss had made this nonnegotiable, imposing a “twenty-four-hour rule.” All client emails, internal or external, now required a response within one day’s time.

Lucas texted Sarah to tell her he had to stay a little late, but that he’d be home in time for dinner with the family.

He knew the drill all too well, even if he had risked leaving this task to the end of the day. As he had guessed, a good percentage of the messages were emails that were FYI (for information only) and could be quickly filed or deleted. Luckily, none of the other emails required more than a quick reply or an attachment of an existing document to fulfill the request. The process was moving along nicely.

As Lucas approached the last few emails, he heard a door open in the distance, along with the sound of humming. He looked at his watch. He had been hoping for another opportunity to ask Ted about those “few questions” he had mentioned when they first met, a little over a week ago.

Lucas was just wrapping up his last email reply—Whew! It had taken only a moment to send the monthly data on customer service wait-times to one of his internal clients—when, over in the next cubicle, he heard Ted emptying the trash can.

“Is that you, Ted?” Lucas reached over to shut down his computer for the night.

“One and the same.” Ted chuckled as he finished dusting and tidying up the desktop of the cubicle next door. “That sounds like Lucas keeping night hours again!”

Ted pushed his cart up to Lucas’s office.

Lucas replied, “Yeah, there’s always more work. Somehow I always have more left to do at the end of the day. I just finished a load of emails I had to respond to before I leave.” Lucas glanced at his computer as it finished shutting down. “Ted, I really enjoyed our conversation the other night. And I’m still curious about those questions you mentioned.”

Ted checked his watch. “Well, if you’ve got a few minutes before you need to go, I could briefly share the first question with you. I figure it’ll take about fifteen to twenty minutes.”

Lucas leaned back in his chair and smiled. “Perfect! If I leave here within a half-hour, I can still get home in time for dinner with my family.”

Ted glanced around. Lining the walls of the corridor running the length of the cubicles were a series of whiteboards. The one across from Lucas was blank. “You mind if I draw a few diagrams on the board there?”

“Not at all,” said Lucas. “I have some markers in my desk here—you can use these.” He pulled open a drawer and pulled out three colored markers. He handed them to Ted.

“Mind if I sit down?” asked Ted.

“Please do,” said Lucas, pointing to the guest chair next to his desk.

“There are actually three vital questions in all. Your answer to the first one will reveal how you see and operate in the world. According to many others I know who have taken this question to heart, it has changed the way their internal environment affects their behavior. And that, in turn, has transformed their relationships at work, at home … in so many aspects of their life.

“Are you ready for it?”

“Bring it on.” Lucas leaned in with a smile.

“Here it is,” said Ted. “Where are you putting your focus? Are you focusing on problems or are you focusing on outcomes?” He raised an eyebrow and waited.

“No doubt about it,” said Lucas. “All we seem to talk about around here are problems and what we’re going to do about them.”

Ted smiled. “Good for you! You just outlined the Problem Orientation, which is one of two primary orientations. The CEO I mentioned said that the Problem Orientation is the default mindset of most people and organizations. But that’s getting ahead of ourselves.

“There’s an organizing framework behind this first vital question that I need to share before we go any further. Guess you could say I am going to toss you a FISBE.”

“Toss me a Frisbee?” Lucas asked.

Ted made a “just a minute” gesture with his finger, got up from the chair, and stepped out into the corridor. On the whiteboard he drew three circles connected by arrows, forming a sort of loop. Above it he wrote: FISBE.

“Nope, it’s a FISBE, not a Frisbee,” he said with a chuckle.

Lucas maneuvered his chair to get a better look at the board.

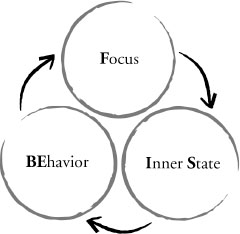

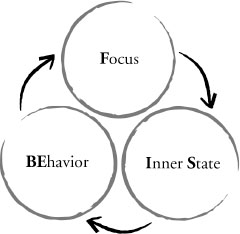

“FISBE is an acronym that describes the human operating system that every one of us is using, all the time,” said Ted. “The F in FISBE stands for focus,” he said, writing the word in the top circle, “and this focus sets up the rest of the operating system. That’s because whatever you focus on, that’s what gets your inner state going. Your inner state is your emotional response to whatever you place your attention on—what you’re thinking about. So the I and S stand for inner state.” Ted added IS to the second circle in the diagram.

“Depending on this emotional response,” he continued, “this inner state then drives your behavior.” He wrote capital BE, for behavior, in the third circle. “So FISBE stands for focus, inner state, and behavior. Got it?”

Lucas looked at the board for a minute and thought it over. “I get the diagram and how the focus leads to an inner state that drives behavior. But why do you call this the human operating system?”

“Good question! Because,” Ted continued, “as my CEO friend pointed out, we human beings are cognitive—or thinking—creatures. Our thoughts set up our focus. We’re also emotional beings. Our emotions determine our inner state. And, of course, as individuals and groups, we take actions and engage in behaviors,” Ted explained.

“Hmm,” said Lucas, squinting at the diagram.

“Your FISBEs—you could also call them mindsets or orientations—have everything to do with how you move through your day and, ultimately, your life. Your primary FISBE drives your behavior, just like the operating system drives that computer you just turned off.

“So here’s where it gets really interesting, Lucas. In the same way you can upgrade the operating system in your computer, you can upgrade your internal operating system as a human being.”

“Interesting analogy,” Lucas said. “I’m listening.”

“Let me share an example of how different FISBEs, or operating systems, can change our experience. Are you game?” Ted leaned against the whiteboard, glanced at the diagram, and crossed his arms.

“Absolutely!” said Lucas.

“So,” Ted said, “here in the Pacific Northwest, we love our beaches. Imagine you’re walking along the beach and it’s a beautiful sunny day. The water of Puget Sound is smooth and lapping gently on the shore. Not far offshore, you see a sloop gently sailing by. Got the picture?” Ted asked.

Smiling, Lucas said, “Sure do!”

“Now let’s assume there are two different people walking along that same beach. One of them looks out at the sailboat and recalls happy memories from childhood when her family often had fun playing at the beach and occasionally going out on a neighbor’s boat. Her inner state is one of happiness and contentment. So, she stops for a moment, smiles, and takes a deep breath, enjoying the salt air.” Ted paused.

“See her FISBE, Lucas? Her focus is on pleasant memories triggered by the boat, her inner state and emotions are positive and serene, so her response—her behavior—is to pause and drink in the moment.”

“Makes sense,” said Lucas.

Ted continued. “Now the other person walking on that beach looks out over the water and sees the same sailboat gliding by. His focus goes to a time in childhood when he and his family were out on a boat and he fell overboard and nearly drowned. His heart starts beating faster as he feels the anxiety and fear of that experience all over again. He turns and quickly walks away from the shore and heads toward the parking lot.

“You can see how the same situation triggered positive thoughts for one person and negative thoughts for the other—their focus was different. This caused them to experience very different inner states, which then led to very different actions, or behaviors. The same situation, with different FISBEs, created two totally different experiences.”

“Interesting,” mused Lucas. “Do those two different examples illustrate the two orientations you mentioned earlier?”

“You’re a quick study, Lucas!” Ted turned to the whiteboard and drew two more loop diagrams.

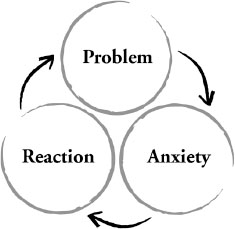

Above one diagram, Ted wrote: Problem Orientation.

“This and the other FISBE is called an orientation. That just means whatever you put your focus on—your orientation—is what sets the whole operating system in motion. This first one, the Problem Orientation,” Ted said, pointing to the board, “is your default orientation as a human being, as I’m sure you’ll quickly see.” Ted paused with a wink and turned back to the board. “It’s also the one you said is so common around here.”

“As you might suspect, the focus here is on problems,” he said, and he wrote Problem in the focus circle. “A problem can show up in all kinds of ways: maybe someone emails you, or calls or texts you. Or maybe someone walks into your office and starts talking about a problem. “As you take in this new information as a problem,” said Ted, “your inner state arises—and that’s going to be some kind of anxiety.” Ted wrote Anxiety in the inner state circle. “Then, depending on how bad you think the problem is, your anxiety could be anything from a little irritation to intense fear. Either way, the inner state of anxiety will trigger you into action.

“This action you take—that’s your behavior, of course—is some form of reaction. There are four ways you might react: fight, flight, freeze, or appease.”

“It sounds pretty dramatic,” Lucas said.

Diagram 3. The Problem Orientation

“It sure can be! At least until you start to see what’s happening in your FISBE,” said Ted. “You might fight the situation in some aggressive way, to try to protect yourself. Or try to get away—take flight, like a bird escaping a barking dog. Or maybe you’re not sure how to react, so you do nothing—you freeze and hope the problem goes away. Last of all, you could react by playing nice and trying to appease, or smooth things over. Whichever way you go, you are caught in a reaction,” Ted concluded. Then he wrote Reaction in the behavior circle.

Ted stepped back and regarded his handiwork. “So you see, here in the Problem Orientation, you focus on problems, which turns on your anxiety, and that drives a reactive behavior. Sound familiar?” Ted asked.

Lucas leaned back in his chair and let out a deep sigh. “Wow. You just described what it’s like almost every day around here!”

“Can’t say I’m surprised.” Ted shook his head. “It’s what I’ve seen in most of the companies I’ve been around. The Problem Orientation seems to be the main operating system within us as individuals. And it’s the main way we relate with others as well. That’s why my CEO friend called it the default orientation.”

“I can see that,” said Lucas. “It’s kind of discouraging, though.”

“Only if you don’t know you’re doing it!” said Ted. “Once you start noticing it, things look a lot more hopeful.”

He scratched his ear. “There’s something deeper here, though,” he went on, “that I should caution you about. Embedded in this orientation, there’s a false assumption and a false hope.”

Ted paused and faced Lucas. “Let me ask you something. When you’re faced with a problem around here and your anxiety flares up, what do you tell yourself you’re reacting to—the problem or the anxiety?”

“The problem, of course!” Lucas quickly answered.

“See, there’s the trick!” exclaimed Ted. “That’s the false assumption.”

Lucas frowned.

Ted continued, “You’re telling yourself you’re reacting to the problem, when really you’re reacting to the anxiety you feel about the problem. If you didn’t feel some level of anxiety, you’d let the situation pass on by. The false assumption is that the problem is driving this operating system. But it isn’t—the Problem Orientation, the operating system, only sets it in motion. It’s actually your anxiety that’s driving the whole shebang.” Ted chuckled, looking over his drawings.

“Wow, I can see that,” Lucas agreed. “I’m not sure what to make of it, but I see what you’re saying.”

“There’s one other thing you have to be careful of,” Ted added. “There’s a false hope underlying this whole way of being, too.” He raised an eyebrow. “The false hope is that if you can just solve the problem, then everything will be okay … or that you’ll then be able to focus on something more important. Right?”

“Of course. That makes sense to me. Why would that be false?” Lucas said.

“Well, let’s see. You said the Problem Orientation describes your experience of your typical workday. So let me ask you something else.” Ted crossed his arms. “Say you’re lucky enough to solve a problem—what typically takes its place?”

Lucas didn’t have to think long. “Another problem. Seems like there’s always a new issue lurking under the last one. I’m just waiting for the next incoming problem!”

“And that’s why it’s a false hope that problems will go away,” Ted responded, and he uncrossed his arms. “As long as you’re working in this operating system—the Problem Orientation—then for every problem you seem to solve, another one will pop up in its place. It’s like that old game of Whack-A-Mole, where as soon as you get rid of one nuisance critter, another one pops up.”

Lucas shook his head and was silent for a few seconds. “Yeah, it’s a downer,” was all he could think to say. “A false assumption and a false hope. But both of those ring true to me.”

“I know what you mean,” said Ted. “So, can you see why you need an upgrade from this operating system?” he asked, pointing over his shoulder at the Problem Orientation FISBE.

Lucas leaned forward and said, “I really do, Ted. No joke. Would you please, please show me a better way to work?”

“And live,” Ted added with a smile. “Sure thing.”

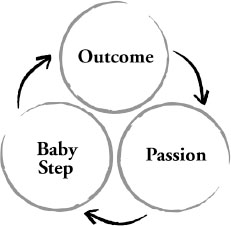

Turning back to the whiteboard, Ted wrote Outcome Orientation above the second diagram.

“I think you’re going to find this one a little easier to stomach,” he said. “It’s a lot more positive, for one thing, and it may feel more familiar than you’d expect. I’m sure you’ve had some experience operating from this orientation, at least from time to time.”

In the focus circle, Ted wrote the word Outcome.

“In this orientation, you have a much different focus. Here your thinking is oriented toward envisioning an outcome. Sometimes the outcome you have in mind is clear—you know almost exactly what it is and how you want it to happen. Other times this outcome may be somewhat vague in your mind, but you have a general idea of the direction you’re heading.

“What’s important is that you care about the outcome you envision. Because when you really care about it, that ignites an inner state of passion,” said Ted, and he wrote the word Passion in the inner state circle. In the behavior circle he wrote Baby Step, then turned to face Lucas.

“That passion,” he continued, “provides the motivational fuel to take the next step in your process toward creating the outcome—whatever that step may be.

“So, in the Outcome Orientation here, the behavior is referred to as a baby step. Because the action you take is usually something that happens little by little, step by step. It could be as small as making a phone call or doing some research or … really anything that’s the next step in your process of creation. I could say more about the idea of baby steps, but let’s save that for when we get into the third vital question.”

“Sure,” Lucas said. He laughed. “My brain is pretty full already! But I’d like to understand the Outcome Orientation a little better.”

Diagram 4. The Outcome Orientation

Ted chuckled. “It always makes me laugh when I say thank you to someone and they say ‘No problem.’ Shows how common the Problem Orientation is in our culture. But, to your question … Let’s see, can you think of a time you were operating from this Outcome Orientation?” he asked.

“Hmm, let me think,” Lucas began. “A time I was focused … on an outcome that I cared about and then took some baby steps to accomplish. Yeah—got it! Finishing my computer science degree.” He took a breath.

“Sarah and I were married then,” Lucas said, “and we knew we wanted to start a family, but I wanted a college degree that was marketable and could support us. I really cared about that—doing everything I could to help take care of my family—though I’m not sure I was all that passionate about computer science. But that’s another story.

“Anyway,” said Lucas, “I was working as a waiter at a decent restaurant, taking classes at night and working my job schedule around daytime classes while Sarah worked as a nanny for a family with a toddler. She had already completed her associate’s degree in early childhood education, but she wanted a job with flexibility so we could work our schedules around each other’s. Sarah was a rock—she really supported me in juggling it all. I guess you could say that every class I took was a baby step.”

Lucas glanced at his desk, at the framed picture of Sarah and the kids. “I feel so lucky and supported by Sarah to this day,” he said. “We love being parents, and I learn a lot from her—and with her.”

“Great example, Lucas!” Ted chimed in. “While you and Sarah were working through your degree, you were plugged into this Outcome Orientation operating system, and you didn’t even know it. The key to this first vital question is to upgrade to the Outcome Orientation as your primary way of thinking, here at work and, really, throughout your life.”

Ted looked at his watch. “Got a few more minutes? I could point out a few differences between these two orientations, if you have the time and interest.”

Lucas looked at his phone and scratched his chin. “Let me text Sarah and ask her if she minds holding dinner for another fifteen minutes. I’ll tell her I have something very interesting to share with her when I get home. That’ll get her attention.”

As Lucas was texting Sarah, Ted turned and wrote the word AIR on the board between the two FISBE diagrams. “Speaking of attention, Lucas,” he said, “that’s one of the differences here, between the Problem Orientation and the Outcome Orientation. AIR stands for three major distinctions between the two FISBEs: your attention, intention, and results. You’ll see these two operating systems have very different ‘airs’ about them.” Ted smiled as he made the air quotes.

“As I said, the A here stands for attention,” he said, pointing to the board. “Here in the Problem Orientation, your attention is on the problem, of course. When this is your default way of being, you go through your day focusing on the things you don’t want and don’t like—which is why you call them problems. You’re almost always scanning your environment for what’s wrong or what’s not working—or you’re on the lookout for another nuisance critter to pop up.”

“Have you been following me around?” Lucas chuckled. “That is exactly how my days seem to go lately.”

“Well, as you adopt the Outcome Orientation and start to use that operating system more consistently,” Ted said, “your attention begins to move naturally toward whatever it is that you do want, and what you really care about. That doesn’t mean you won’t have any more problems, but it does mean there will be a big shift in your relationship to those problems. Instead of seeing problems everywhere you look, you start taking on only the problems that need to be solved to create the outcome you want. And that brings us to the I in AIR—which stands for your intention.

“But first I have a question for you, Lucas.”

“Sure,” said Lucas.

“In the Problem Orientation, your intention is to get rid of, or get away from … what?” Ted asked.

“The problem!”

“You got it, but if this was a game show, you would lose a point there!” Ted shook his hands in the air and laughed. “That was actually a trick question. Remember the false assumption I mentioned?”

“Oh yeah,” Lucas said. “The assumption is that I’m reacting to the problem itself, when really I’m reacting to the anxiety I feel about the problem. Is that it?”

“Smart fella.” Ted nodded. “Your intention is really to get rid of, or get away from, your anxiety through various behaviors—either fight, flight, freeze, or appease. Behaviors you hope will solve the problem. But, as we’ve already said, it’s the anxiety that is really the driver in this problem-focused operating system. And in just a minute you’ll see why that is.

“But first, look at intention in the Outcome Orientation. When you operate from here,” said Ted, pointing to the Outcome Orientation FISBE, “your intention is to move toward the outcome and, through the baby steps, or the actions you take, to bring that intention into being over time.”

Lucas joined in. “So, the difference is between moving away from what you don’t want—the problem—and moving toward the outcome you do want.”

Ted grinned. “Yep!”

“That’s great, Ted,” said Lucas with a smile. “So, the A stands for attention, and the I stands for intention. Tell me again what the R stands for?”

“Ah, now you’re going to see why these two operating systems are so very different,” said Ted as he turned back to the whiteboard.

Below each of the FISBEs, Ted drew what looked like a backward L lying on its side. Alongside the short vertical line, he wrote Results. Below the longer horizontal line, he wrote Time.

“Here’s the real whopper between these two orientations. Over time, they lead to two very different patterns of results.”