A week after Lucas met Kasey for coffee, he was still thinking a lot about both his time with Ted and the exercises Kasey had shared with him.

One evening at home, Lucas kissed the kids good night and left Sarah to tuck them in. Lucas assumed that Sarah would unwind from the day as she usually did, with her latest novel on loan from the library, and he decided to retreat to his study for a little while. Taking out his journal and pen, he began capturing some thoughts from his time with Ted and his coffee break with Kasey.

“It’s surprising how much of the time I default to the Problem Orientation,” Lucas wrote. He listed a few ways he had caught himself reacting to things recently. Just that morning, he had been in a staff meeting with his fellow customer service team leads. His boss was running the meeting. As Lucas listened to different people speak, he realized how often he heard whatever was being said—especially when his boss was saying it—as some kind of problem. He would then react to the perceived problem, at least in the privacy of his mind.

Just then, Lucas heard a light tap on his study door.

“What are you up to in there?” said Sarah, peeking into the study.

He motioned her in. “Pull up a chair.”

Then Lucas did his best to describe what Ted had taught him. He showed Sarah the FISBE diagrams—how a person’s focus engages their inner state, and how their behavior proceeds from that. He showed Sarah the diagram of the Problem Orientation FISBE with its focus on problems, anxiety, and reacting. Then he showed her the Outcome Orientation FISBE that leads to taking small empowering actions one at a time—actions Ted had called baby steps.

Sarah listened with interest. “I could use this stuff myself,” she concluded. “When do you think you’ll have a chance to learn more from this guy?”

“I really don’t know,” said Lucas. “It’s kind of a spontaneous thing. I hope it’s not too long, though. I’m already knee-deep in what he’s taught me so far, and I want to learn more!”

Sarah smiled and nodded. She seemed as curious as Lucas to hear what else Ted would have to say.

For the next couple of weeks, Lucas was working on a project that filled his afternoons with meetings. He still hadn’t seen Ted, and he was anxious for the next lesson. So one morning, Lucas checked in with Sarah to make sure she was okay with him staying late, on the off chance that he and Ted might connect. Sarah had enthusiastically agreed. “Anyway, it’s about time the kids had another pizza night,” she said. Then added, “Of course, if you do meet up with Ted, I expect you to fill me in.”

“It’s a deal.”

That night, Lucas finished reading a report from one of the members of his team and smiled when he realized there was very little editing he needed to do. Just as he clicked Save on the document, he heard a door open down the corridor and the unmistakable humming of a gentle tune.

Standing up, Lucas peered over the wall of his cubicle and said loudly, “Good evening, Ted! When you make your way down to this area, I’d love it if we could visit for a bit.”

“Absolutely, young man!” said Ted with a big smile. “Nice to see you! Should be coming by there about ten minutes from now.”

“Great!” Lucas pulled his journal out of his backpack. These days he always kept it nearby in case he wanted to capture some insight or observation. He looked through the dozen or so pages he had filled since his coffee with Kasey.

Lucas had to chuckle at one entry he’d written just a few days ago. It described how he had returned to his desk from yet another long meeting, sat down, and clicked Download on his email. As he watched the twenty or so emails stacking up before his eyes (he’d only been away from his desk for an hour). Lucas noticed his anxiety rising and realized he was seeing every email as a problem to react to.

As he continued reading his journal, he saw that there had been many times recently when he had caught himself in the Problem Orientation and noted his feelings of anxiety along with his resulting reactive behaviors and actions. It was a little discouraging to see how often he had engaged in that pattern. But on a positive note, he had been taking Kasey’s advice to also reflect on his experience anytime he noticed he was operating from the Outcome Orientation.

It was interesting how many of his reactions started with a single email. And what a big difference it made when he focused on the outcome as he made his way through these essential communications.

One recent email was from a senior manager who had criticized a report submitted by one of Lucas’s team members. Reading the critical comments, Lucas had felt himself tensing up. There was an immediate, strong impulse to do something—anything—to dispel his anxiety. He could either forward the email to the author of the report and add his own criticism, or reply to the senior manager’s email and defend his teammate.

Instead, Lucas had paused. He had asked himself, “What outcome do I want here?” In the end, he wrote an email to the senior manager and copied his teammate—the email asked for more information about what kind of outcome the manager had wanted that the report had not addressed. As Lucas read this journal entry, he recalled how relieved and even joyful he had felt when the senior manager’s reply came back saying that, overall, the report provided good information, but one area had not been covered as specifically as it could have been. The senior manager even apologized for not stating clearly what he needed in the report! Then he spelled out in some detail how the report could be expanded to better meet his criteria.

What a savings in time, energy, and drama. In the past, Lucas might have spent a lot of effort reacting to the feedback, instead of focusing on how best to address the issue. When he focused on the outcome he wanted, the action he needed to take just seemed to present itself naturally.

Lucas skimmed through a few more of his journal entries. He noticed that, as Kasey had predicted, his thoughts had grown much more positive.

Many of his reflections had an “I can do this” quality about them. As he had written about his feelings and emotions, he had used upbeat words like optimistic, empowered, and energized. And Lucas noticed something else, too:

The actions he took when he was in the Outcome Orientation were different from the reactions he took when he got caught up in the Problem Orientation. At those times when he focused on the outcome, Lucas found himself more often collaborating with others, coming up with fresh ideas, and even taking risks to speak up. Of course, it had been a lot easier to speak up with his previous boss than it was now.

It surprised Lucas to realize that he actually enjoyed solving problems when he simply viewed them as barriers to the outcome he wanted to accomplish. He also noticed that from the Outcome Orientation, he dealt with mistakes and setbacks differently, making well-considered choices about how to move forward.

Lucas was lost in reflection when Ted rolled his cleaning cart up and parked it next to Lucas’s cubicle. “It’s good to see you again,” Ted said. “I was gone last week, so I hope you didn’t miss me.” He gave Lucas a wry smile.

“Oh?” Lucas replied. “Where did you go?”

“I was on vacation,” Ted said. “My wife and I went down to Southern California to relax, soak up some sun, and spend time with an old friend I’ve known for a few years. Went to the beach, of course. Beautiful! I ran into a young man out there and we ended up talking over some of the same stuff you and I have been getting into. Nice fella.”

“It sounds like you really enjoyed the time off,” said Lucas.

“We surely did,” said Ted. “So how’ve you been, my friend?”

“Things have been going pretty well,” said Lucas. “You gave me lots to think about. I’ve been reflecting on the first vital question and where I put my focus. I’ve been noticing how often I default to that reactive way of thinking as I go through the day.

“Hey, and I also connected with someone you apparently got to know when she was managing the Customer Call Center. Do you remember—”

“Kasey!” Ted interjected. “I do remember her, very well. Soon as you mentioned the call center, I knew who you were talking about. Kasey really absorbed the three vital questions—we had some wonderful conversations.”

“I could tell she learned a lot from those conversations,” Lucas replied. “She and I met for coffee several weeks ago, and she walked me through some of the exercises you taught her. Since then I’ve been journaling about my thoughts, feelings, and actions, as well as my reactive triggers and strategies. I can’t believe how often I’ve been reacting without even being aware of what’s behind it.”

“That’s great!” said Ted. “I think you may be experiencing an upgrade in your internal operating system.” He laughed. Then he added, “I’d like to hear some of those insights, Lucas, if you wouldn’t mind.”

“I’d love to.” Lucas took a few minutes to read some of his journal entries to Ted. It felt good to share what he had been noticing about his reactive patterns and how—even when problems presented themselves—he had tried to stay focused on outcomes and take action from the Outcome Orientation.

“Nice job applying your insights,” said Ted. “Sounds like you’re not just using the approach at work, you’re taking it back to the home front, too.” Then he added, “Before I tell you about the second vital question, I want to tell you something important about the ideas of Victim and Creator that will get us from the first vital question to the second. That is, if you have the time.”

“You bet!” said Lucas. “In fact, I stayed late today hoping we’d have another chance to talk.”

“Good man.” Ted continued, “I want to explain how the Problem Orientation is actually a Victim Orientation, because usually we feel victimized by the problems we’re reacting to. On the other hand, the Outcome Orientation is really a Creator Orientation, from which you create outcomes and the baby steps you’ll take to accomplish those outcomes. As you’ve already noticed, sometimes the steps you take are setbacks or mistakes. Those unexpected events make the whole process quite interesting. So there’s your operating system in a nutshell. And out of this operating system you can consciously choose how you’re going to respond to whatever comes your way.”

Lucas responded, “It’s been a real eye-opener to be able to notice how I’m thinking and acting throughout the day.”

“That’s great news, Lucas! Now that you’ve got a handle on the Victim and Creator Orientations, we can move on to the second of the three vital questions. You’ll see that the answer to this question depends heavily on which of the two orientations, or FISBEs, you are operating in.

“The question is this: How are you relating? There are actually a few layers to this one, as I learned from my CEO friend. One is, How are you relating to other people? Another is, How are you relating to what is going on in your life? And the third is, How you are relating to yourself?

“The key here is, are you relating in ways that are going to produce or perpetuate drama, or are you relating in ways that empower yourself and others to be more resourceful, resilient, and innovative?”

As Ted spoke, Lucas felt he was listening in a whole new way, as though he was claiming this second vital question as his own. As the words “produce or perpetuate drama” resonated in his mind and memories, Lucas shook his head. “Gosh, Ted, I can’t tell you how much drama goes on around here. Sometimes I feel like I’m living and working in a soap opera!”

“Yes,” said Ted. “Drama goes unchecked in most workplaces, I’d say. Unfortunately, it seems to be the default system that takes over many of our life situations. Drama is the natural product of an environment rooted in the Problem Orientation, which we know is also the Victim Orientation.” He paused as Lucas nodded in agreement.

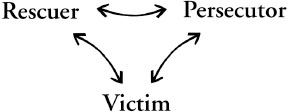

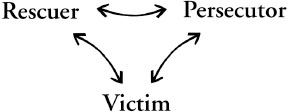

“Years ago,” Ted continued, “a psychiatrist by the name of Stephen Karpman identified a triangle of relationship roles that make up what you might call the Dreaded Drama Triangle, or DDT. You may know that DDT is a very toxic chemical, so it’s a fitting name for the toxic way these roles work their drama on one another.”

Ted picked up a marker and turned to the whiteboard across from Lucas’s cubicle. On it Ted drew a downward-pointing triangle. At the bottom point of the triangle he wrote Victim.

“The central role in the DDT is the role of Victim, Lucas. And here’s a rule you can go by: anytime you find yourself complaining—whenever there is something you want or care about that you feel powerless to have, do, or be—then you know you’re stuck in the Victim role,” Ted explained.

“That’s how I feel a lot of the time here at work,” said Lucas. “And, when things get really bad, I feel a bit hopeless that it will ever get any better.”

“I’m sure there are times when you feel victimized by things that are happening in your life, whether it’s here or elsewhere,” Ted said. “We all feel victimized from time to time. You can think of victimization along the lines of the old ‘scale from one to ten.’ Maybe at one, you’re waiting in a long line at the grocery store, while on the other end of the scale, say ten, you could be in a war zone or in the midst of an earthquake, or really any situation that poses an immediate threat to your physical safety.”

Lucas nodded. “Okay. I see what you mean.”

“But feeling victimized is very different from victimhood,” said Ted. “Sadly, victimhood can become a whole self-identity, a way of being in life that keeps you feeling like you have no choice, that life is just happening to you and you can’t do anything to change it.

“When you ask yourself this second vital question, How am I relating? it’s a direct challenge to that stance of victimhood. But at the same time you’re acknowledging, ‘Hey, this feeling of victimization is all part of the human condition. It’s not who I am, it’s just part of my experience.’”

Ted continued, “You don’t strike me as someone who lives his life in a state of victimhood, Lucas. From what you’ve shared with me, it seems you have a wonderful home life. But it definitely sounds like you feel victimized by some of what’s happening here at work. Is that a fair impression?”

Lucas nodded. “Yes, that’s right. I’m pretty happy in life, for the most part. Though I guess you’ve heard me doing quite a bit of complaining about work.”

“Makes sense to me.” Ted raised his marker again and turned back to the whiteboard. “So anytime you—or anyone else—inhabits the Victim role, there has to be a Persecutor. That’s the second role in the Dreaded Drama Triangle.” Ted wrote Persecutor at the upper right corner of the triangle.

“While you might think of a Persecutor as a person—like your new boss, maybe—there are other forms a Persecutor can take. It might be a health condition, such as heart disease or diabetes. The Persecutor also could be a situation such as a hurricane or earthquake, or any of the other tragic events we see on the news. Or it could just be one of those everyday annoyances like getting stuck in rush-hour traffic or being stuck in line at the grocery store, like I mentioned earlier.”

Lucas sat back and considered Ted’s diagram. “Okay, now I want to make sure I understand this. A Persecutor could be a person, or a condition, or a situation. I can think of a few examples. You already mentioned my boss, so that’s a person. My dad was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes about ten years ago, and I remember him really feeling down about that, so I guess you could say he felt victimized by the disease. And you are absolutely right about the news! Wars, hurricanes, earthquakes, gun violence. It seems like the list of Persecutors could go on forever!”

“Those are all good examples,” said Ted. “When the Persecutor is a person, often they seek to control and dominate the drama. They actually fear their own victimization, so they become aggressive. Then they can easily blame the Victim for whatever is happening.

“And whatever form the Persecutor takes, he, she, or it is dominating the time, attention, and energy of the person in the Victim role. The Persecutor is ‘the problem’ that the Victim is reacting to out of fear or anxiety.” Ted put down his marker. “Does that sound familiar?”

Lucas smiled. “Yes. I think you’re describing the FISBE of the Problem … I mean, the Victim Orientation.”

“You got it!” Ted turned back to the whiteboard. “There’s one last role to complete our DDT here.” As he wrote the word at the upper left corner of the triangle, he said, “And that’s the Rescuer.”

“Someone coming to save the day?” asked Lucas.

“Could be,” responded Ted. “It could definitely be a person, but not necessarily. I’ll come back to that in just a minute.

“There are three ways a Rescuer can come in and complete the DDT. One, the Victim goes looking for a Rescuer and invites them into the drama. Second, someone intervenes to either take care of or fix the Victim, or goes after the Persecutor to protect the Victim. Then the third kind of Rescuer could be someone or some situation that the Victim hopes will emerge to, as you say, ‘save the day.’

“When a Victim goes looking for a Rescuer,” Ted continued, “they may be seeking something to help them get some distance, or numb out their feelings of powerlessness or hopelessness. That something could range from zoning out and binge-watching a TV series to having an extra glass of wine, or worse. That’s why I call the Rescuer the ‘pain reliever.’”

“Hmm,” Lucas responded. “I can see how I sometimes go home and retreat into my study to escape into social media or news sites on the internet—and sometimes, I admit, with that extra glass of wine. And when I stop to think about my situation here at the office, I can see I’ve been thinking of Kasey as a sort of Rescuer.”

“That’s a great insight, Lucas,” Ted said. “If Kasey is practicing what she and I talked about—and I would bet she is—then I think you’ll find she knows how to be a helpful support, without falling into the Rescuer role. See, the shadow side of the Rescuer individual is that, while their actions are usually well-intended, taking care of or fixing the Victim only reinforces the Victim’s feelings of powerlessness and resentment about their victimization.”

Ted went on, “And what’s more, the Rescuer takes actions based on fear, too, just like the Persecutor does. The Rescuer’s fear is that they will not be needed—so they seek out a Victim they can ‘help.’ This renews the Rescuer’s sense of purpose—to fix or protect or take care of the Victim. When three individuals are involved, then all three roles—Victim, Persecutor, and Rescuer—are locked in reaction to fear, each using a different strategy to stave off that fear, of things spinning out of control.

“So, there you have it—the Dreaded Drama Triangle, better known as the toxic DDT.” Ted gestured to the simple diagram he had drawn.

Diagram 9. The Dreaded Drama Triangle

Lucas took out his journal and drew the DDT. “I’d like to hear more, Ted. But first I want to take a few minutes to capture some notes, okay?”

“Great. I’ll work my way down this corridor a little ways,” Ted said, and he gave the cart a push to get it moving. “Just holler when you’re ready to hear about the antidote to the toxic DDT.”

“The antidote?” Lucas asked.

“Absolutely,” Ted called as he headed down the aisle between the cubicles. “It’s all about upgrading your orientation—your internal operating system—from the Victim Orientation to a Creator Orientation. Once you can do that, you’re in for a whole new dynamic!” He waved. “I’ll be happy to swing back by and share that with you when you’re ready. Just holler.”

Lucas scribbled a few notes from what Ted had shared about the DDT. He was looking forward to telling Kasey about what he’d just learned. He wondered how she dealt with drama in her area of the organization. And he wondered if Kasey had been able to apply any of Ted’s wisdom during her time working under the same boss that Lucas worked for now.

Lucas also reflected a bit on how he and Sarah and the children could get into contentious situations at home. He could certainly see there were times when they got swept up in the DDT.

After several minutes, Lucas stood up and looked down the corridor. He could hear Ted humming, but couldn’t quite see him. Then Lucas saw Ted’s head pop up from several cubicles down.

“Ready when you are!” Lucas called out.

“Be there as soon as I finish dusting up over here,” said Ted.

When Ted returned, he asked Lucas for a whiteboard eraser.

“Thanks,” he said as he turned to erase the Dreaded Drama Triangle diagram.

“Wish I could say it’s just this easy to erase the Victim, Persecutor, and Rescuer roles from the way we relate to one another, but I’m afraid these roles are deeply wired in human beings, and we all fall into them sometimes,” said Ted.

He turned around and leaned against the whiteboard, facing Lucas. “Now that you have seen the Victim Orientation, I suspect you can see that it’s our default operating system. It can run our entire lives if we let it. But, what if I told you we could take this whole thing one step further?”

“I can’t wait,” said Lucas.

“There’s a much more effective and enjoyable way to relate, once you start to develop a Creator Orientation,” Ted continued. “The CEO I told you about—he really opened my eyes with this one. And, I have to say, I now take it rather personally.”

“What do you mean?” Lucas asked.

Ted raised his marker to the whiteboard and wrote TED* (*The Empowerment Dynamic) at the top.

“Oh, wow!” Lucas exclaimed. “Did he name it after you?”

“Nope, I wish he had.” Ted chuckled. “But I’m honored to share the same name as the triangle of roles and relationships I’m about to show you.”

Lucas turned to a fresh page in his journal, picked up his pen, and smiled. “Ready when you are!”

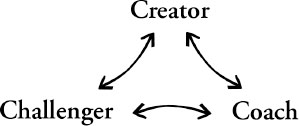

Again Ted drew a triangle on the board, but this time it pointed upward. “Remember how I said the DDT thrives in the Victim Orientation. And how the acronym DDT is symbolic of the toxic relationships in the Dreaded Drama Triangle?”

“Absolutely.”

“Well,” Ted went on, pointing to the new triangle, “the roles in TED*—The Empowerment Dynamic—are the antidotes to the toxic roles of the DDT.” Ted grinned. “I already gave you a hint about what the primary TED* role is, Lucas.”

“You did?” Lucas squinted at the empty triangle on the whiteboard.

“Yes! Didn’t I tell you I’d have a quiz for you occasionally?” Ted laughed, playfully wagging his marker.

“So, here it is: What is the antidote or—here’s a big clue—the upgrade to the Victim Orientation?”

“Oh sure! It’s a Creator Orientation,” said Lucas, relieved.

Ted wrote Creator at the top of the triangle. “You got it. The antidote to the role of Victim is the role of Creator. And Creator is the central role of TED*—The Empowerment Dynamic.

“Now, being a Creator has two main characteristics. First, a Creator focuses on creating outcomes, just as we talked about earlier. The second characteristic—and this is really important—is that a Creator takes responsibility for the way they respond to whatever happens in their experience. Creators do this even when they feel victimized.”

Lucas frowned. “Wait a minute. Are you saying that a Creator chooses a fight, flight, freeze, or appease reaction to whatever is going on? Isn’t that what Victims do?”

“You’re so right,” Ted said. “The choosing is the big difference here, as well as the range of choices. There is actually a big difference between just reacting to a situation and choosing how to respond to it.”

Ted put down the whiteboard marker. He reached into his back pocket, took out his wallet, and pulled out a folded piece of paper. As Ted unfolded it, Lucas could see it was well-worn around the edges.

“My CEO friend gave me this,” Ted said. “Right here are three quotes from a guy named Victor Frankl, who was imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps when he was a young man—talk about being victimized! During that awful experience, Frankl had an epiphany that he credits with allowing him to survive. He explains, better than I can, why choosing our response is so much more powerful than merely reacting.”

Ted handed Lucas the piece of paper. “Read it out loud, my friend.”

“Sure,” said Lucas. He read:

“Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

“When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.”

“Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

When Lucas finished reading, he sat for a moment in silence.

Ted cleared his throat and rubbed his chin. “These words came from a man—he was a psychiatrist—who lived through one of the most horrible experiences imaginable. Yet he came to these great insights. Can you see the difference here, between reacting as a Victim, which Frankl easily could have done, versus choosing to respond as a Creator?”

“I’m almost speechless,” Lucas said slowly. “This makes my challenges with my team and my new boss look like a walk in the park.” He started to hand the piece of paper back to Ted.

“You keep it—it’s yours now,” Ted said. “I have them memorized anyway.” He turned back to the board and picked up a marker. At the lower left corner of the triangle he wrote Challenger.

“The antidote to the DDT role of Persecutor … is the TED* role of Challenger. Challengers spark learning and growth. When something happens and you feel victimized, if you can ask ‘What can I learn from this person, this condition, or this situation?’ instead of reacting to it as though it’s your Persecutor … well, then you’ve unlocked the secret to the Challenger role. That’s what Victor Frankl did.” There was a moment of silence, then Ted continued.

“Challengers call forth learning and growth. Sometimes the Challengers in your life are aware of the role they’re playing. These are conscious, constructive Challengers who inspire and evoke learning. Have you ever had a boss who actively challenged you to learn and grow?”

Lucas thought for a moment. “Sure,” he said. “Actually, my previous boss was good at giving me assignments that really made me stretch. In fact, he named me team lead of my group just before he was promoted. That’s how I ended up reporting to my new boss. When my former boss gave me the job assignment I have now, he said it was intended to be a developmental experience—in learning to lead others. I can definitely say I’m learning a lot, even if it’s not always pleasant.”

Ted nodded, “Yes, exactly. Yet oftentimes the Challengers in our lives are unpleasant situations, or people …”

“Like my new boss,” Lucas interjected.

“Like your new boss,” Ted agreed. “You learn from the tough, unwanted, and unwelcome experiences as much or more than you can learn from the positive things that happen. Just one unpleasant jolt can really provoke you to learn and grow. You might call these unconscious, deconstructive Challengers.”

Lucas frowned a little. Ted continued: “What I mean by that is, sometimes there’ll be people who aren’t intentionally challenging you, but you may experience them that way. When Victor Frankl had his epiphany, it gave him the amazing insights that enabled him to see his Nazi captors as Challengers, rather than as Persecutors. And he did it by ‘deconstructing’ the situation to discover what he could learn from it.”

Ted went on, “Also, when you experience something like an illness or an accident, you can’t really say those circumstances or situations are conscious in the human sense. So you may have to dig to find the lessons hidden in them. You mentioned that your dad had diabetes. I’ll bet he learned a lot from that situation.”

Lucas responded, “As a matter of fact, he did. Dad shared with me some of the lessons he learned about the importance of diet and exercise and how the body processes sugar, that sort of thing. So, yes, I can say he learned from diabetes as a Challenger.”

“There you go,” said Ted. “The bottom line is that Challengers call out our potential for learning and growth. And, when you take on the role of a Creator, you can look at virtually any experience as an opportunity to learn.”

On the whiteboard Ted wrote the word Coach under the lower right corner of the TED* triangle and said: The antidote to the role of Rescuer in the DDT is the role of Coach in TED*.

“A Coach supports a Creator,” said Ted, “by asking questions that help clarify that Creator’s intended outcomes or help the Creator to see their current reality more clearly. Coaches also help Creators understand what they’re learning and support them in deciding what actions they’ll take.

“In the Dreaded Drama Triangle, a Rescuer may be well-intentioned, but they actually end up reinforcing the Victim’s sense of powerlessness. In The Empowerment Dynamic, a Coach respects the person or group they are supporting by seeing them as ultimately creative and resourceful. A true Coach will never try to take away a Creator’s power to choose their own responses and actions. Unlike a Rescuer, a Coach knows how to help while leaving that power with the Creator, where it belongs.”

Lucas nodded as he finished copying the TED* triangle into his journal. “I know some people, like our friend Kasey, work with an executive coach when they’re engaged in executive leadership development.”

“That’s true—and that is a professional coach,” said Ted. “But the role of Coach we’re talking about in TED* here, that doesn’t have to be a trained professional. Not at all. You can act as a Coach right now in your leadership role with your team. You can be a Coach with your friends and family members. Believe it or not, you can even be a Coach with your boss.”

“You’re kidding!” Lucas laughed.

“Anytime you’re asking questions to clarify outcomes, to help others and yourself think through things, you’re being a Coach. It’s an important part of being a leader,” said Ted.

“Hmm.” Lucas mused. “I’ll have to sit with that idea for a while. It’s pretty hard to imagine being a Coach with my boss.”

Ted chuckled. He placed the cap on the marker and set it down in the tray of the whiteboard.

“One more thing,” Ted said, “and then it’s back to work for me.

Diagram 10. TED*

(*The Empowerment Dynamic)

“Just as all three roles in the DDT are Victim-oriented … in TED*, the roles of Creator, Challenger, and Coach are Creator-oriented. And you can shift in and out of these three roles as you go about co-creating outcomes and choosing responses to any challenges you have with others.” Ted pointed to the new triangle on the board.

Lucas looked down at the TED* triangle in his journal, then flipped back to the previous page, where he had drawn the DDT. As Ted returned to his cart, Lucas said, “I just noticed the TED* triangle is pointing upward while the DDT points downward. Is there a reason for that?”

“Nothing gets past you, does it?” Ted laughed. “There’s definitely a reason for that! The DDT points down to show that this triangle of relationships is unstable—it symbolizes the ‘downer’ or negative energy between the three roles.

“On the other hand, the TED* triangle sits on a solid base and points upward, quite optimistically. It symbolizes how, as a Creator, you’re focused on continuing to grow and develop, and to create positive outcomes.”

“I like that.” said Lucas. “The upward energy of being a Creator and learning to co-create with others as a Challenger and Coach—that’s what I want. Oh, and I’m having coffee with Kasey again in a couple of days. I’m looking forward to talking with her about the DDT and your namesake—TED*.”

As he began rolling the cart away, Ted grinned. “You can learn a lot from that Kasey. Give her my regards, my friend.”