I WAS IN LOVE ONCE. I THINK LOVE IS A BIT OF heaven. When I was in love I thought about that girl so much I felt like I was going to die and it was beautiful, and she loved me, too, or at least she said she did, and we were not about ourselves, we were about each other, and that is what I mean when I say being in love is a bit of heaven. When I was in love I hardly thought of myself; I thought of her and how beautiful she looked and whether or not she was cold and how I could make her laugh. It was wonderful because I forgot my problems. I owned her problems instead, and her problems seemed romantic and beautiful. When I was in love there was somebody in the world who was more important than me, and that, given all that happened at the fall of man, is a miracle, like something God forgot to curse.

I no longer think being in love is the polar opposite of being alone, however. I say that because I used to want to be in love again as I assumed this was the opposite of loneliness. I think being in love is an opposite of loneliness, but not the opposite. There are other things I now crave when I am lonely, like community, like friendship, like family. I think our society puts too much pressure on romantic love, and that is why so many romances fail. Romance can’t possibly carry all that we want it to.

Tony the Beat Poet says the words alone, lonely, and loneliness are three of the most powerful words in the English language. I agree with Tony. Those words say that we are human; they are like the words hunger and thirst. But they are not words about the body, they are words about the soul.

I am something of a recluse by nature. I am that cordless screwdriver that has to charge for twenty hours to earn ten minutes use. I need that much downtime. I am a terrible day-dreamer. I have been since I was a boy. My mind goes walking and playing and skipping. I invent characters, write stories, pretend I am a rock star, pretend I am a legendary poet, pretend I am an astronaut, and there is no control to my mind.

When you live on your own for a long time, however, your personality changes because you go so much into yourself you lose the ability to be social, to understand what is and isn’t normal behavior. There is an entire world inside yourself, and if you let yourself, you can get so deep inside it you will forget the way to the surface. Other people keep our souls alive, just like food and water does with our body.

A few years back some friends and I hiked to Jefferson Park, high on the Pacific Crest Trail at the base of Mount Jefferson. One evening we were sitting around a campfire telling stories when we spotted a ranger slowly walking toward our camp. He was a small man, thin, but he moved slowly as though he was tired. He ascended the small slope toward our fire by pushing his hands against his knees. When he met us he did not introduce himself, he only gazed into the fire for a while. We addressed him, and he nodded. He kindly asked to see our permits. We went to our tents and to our backpacks and brought the permits to him unfolded. He studied each of them slowly, staring at the documents as if he had slipped into a daydream. They were simple documents, really, just green slips of paper with a signature. But he eyed them like moving pictures, like cartoons. Eventually he handed our permits back to us, smiling, nodding, looking awfully queer. And then he stood there. He leaned against a tree only two feet from our campfire and watched us. We asked him a few questions, asked him if he needed anything else, but he kindly said no. Finally, I figured it out.

He was lonely. He was alone and going nuts.

He had forgotten how to engage people. I asked him how long he had been at Jeff Park. Two months, he said. Two months, I asked, all by yourself ? Yeah, he said and smiled. That’s a long time to be alone, I told him. Well, he said to me, this conversation has worn me out. He put his hands in his pockets and smiled again. He looked out into the distance and stretched his neck to look at the stars.

“Do believe I will head back to camp,” he said. He didn’t say good-bye. He walked down the little hill and into the darkness.

I know about that feeling, that feeling of walking out into the darkness. When I lived alone it was very hard for me to be around people. I would leave parties early. I would leave church before worship was over so I didn’t have to stand around and talk. The presence of people would agitate me. I was so used to being able to daydream and keep myself company that other people were an intrusion. It was terribly unhealthy.

My friend Mike Tucker loves people. He says if he isn’t around people for a long time he starts to lose it, starts to talk to himself, making up stories. Before he moved to Portland he was a long-haul trucker, which is a no-good job for a guy who doesn’t do well alone. He said one time, on a trip from Los Angeles to Boston, he had a three-hour conversation with Abraham Lincoln. He said it was amazing. I bet it was, I told him. Tuck said Mr. Lincoln was very humble and brilliant and best of all a good listener.

Tuck said prostitutes would hang out at truck stops, going from truck to truck asking the guys if they needed company. He said one night he got so lonely he almost asked a girl to come in. He didn’t even want to have sex. He just wanted a girl to hold him, wanted somebody with skin on, somebody who would listen and talk back with a real voice when he asked a question.

Sometimes when I go to bed at night or when I first wake up in the morning, I talk to my pillow as if it were a woman, a make-believe wife. I tell her I love her and that she’s a beautiful wife and all. I don’t know if I do this because I am lonely or not. Tuck says I do this because I am horny. He says loneliness is real painful, and I will know it when I feel it. I think it is interesting that God designed people to need other people. We see those cigarette advertisements with the rugged cowboy riding around alone on a horse, and we think that is strength, when, really, it is like setting your soul down on a couch and not exercising it. The soul needs to interact with other people to be healthy.

A long time ago I was holed up in an apartment outside Portland. I was living with a friend, but he had a girlfriend across town and was spending his time with her, even his nights. I didn’t have a television. I ate by myself and washed clothes by myself and didn’t bother keeping the place clean because I didn’t know anybody who would be coming by. I would talk to myself sometimes, my voice coming back funny off the walls and the ceiling. I would play records and pretend I was the singer. I did a great Elvis. I would read the poetry of Emily Dickinson out loud and pretend to have conversations with her. I asked her what she meant by “zero at the bone,” and I asked her if she was a lesbian. For the record, she told me she wasn’t a lesbian. She was sort of offended by the question, to be honest. Emily Dickinson was the most interesting person I’d ever met. She was lovely, really, sort of quiet like a scared dog, but she engaged fine when she warmed up to me. She was terribly brilliant.

I had been living in that apartment for two years when I decided to cross the country to visit Amherst, Massachusetts, where Emily lived and died. Back then I imagined her as the perfect woman, so quietly brilliant all those years, wrapping her poems neatly in bundles of paper and rope. I confess I day-dreamed about living in her Amherst, in her century, befriending her during her days at Holyoke Seminary, walking with her through those summer hills she spoke so wonderfully of, the hills that, in the morning, untied their bonnets. My friend Laura at Reed tells me that half the guys she knows have had crushes on Emily Dickinson. She says it is because Emily was brilliant and yet not threatening, having lived under the thumb of her father so long. She thinks the reason guys get crushes on Emily Dickinson is because Emily is an intellectual submissive, and intellectual men fear the domination of women. I don’t care why we get crushes on Emily Dickinson. It is a rite of passage for any thinking man. Any thinking American man.

I only tell you all of this to show you how bad it gets when you aren’t around real people for a long time. I tell you of Emily Dickinson because she reminds me of the first time I thought, perhaps, I had lost my mind in isolation. I know now it was an apparition of loneliness, but I cannot tell you how very real it seemed that evening in Amherst. The other times I had seen her it was all invention; I was creating her out of boredom. But this was different.

I had driven from New York City to Boston the night before and had slept in my car. I stopped in Boston because I was too tired to drive the night. I was so cold under a towel I turned and rubbed against a seat belt that knotted itself in my back and against the handle of the door that crowded my head. I lay there in the backseat and stared at the roof of the car, thinking about Emily Dickinson. I hardly got any sleep. In the morning I doped up on coffee and started on the last leg of my journey, the leg that led to Amherst.

All the pretty girls at UMASS were running in their sweats that afternoon, the kids out smoking on the lawn, the trees behind them just sticks of things, just cobalt sky out for a walk. The place is lovely in the winter, very smart feeling, very bookish. The big houses are not close together. Red brick and ivy. Long lawns.

Across town from UMASS is Amherst College. Emily’s grandfather started Amherst College because he wanted women to know the Bible as well as men. He was all vision and no hands, it seemed, and the place went bankrupt nearly immediately. The school was saved years later by the man’s son, Emily’s father, who was not like her grandfather in that he did not believe in the freedom or equality of women. Emily’s father kept women down. Austin, Emily’s brother, not Emily, was expected by the family to publish, to be a great writer.

I was thinking about these things when I circled Amherst College and stopped at the Jones Library where some handwritten notes from Emily are kept, scribbles mostly, gentle pencil on a yellowed sheet within a glass case. It was like magic looking at them. I felt ashamed because I knew I had been reading her for only a year, and yet I felt as though I knew her, as though we were dear friends, what with her living in the apartment in Oregon with me and all.

The man at Jones Library told me where to find the homestead, not much of a place, he said, and indeed I had passed it on the way into town without knowing it. I thought I would have felt it in my chest or sensed it to my right. I thought it would have been largely marked. I followed the man’s instructions and walked from the library down along the shops back toward Boston a mile. Her house is not very much like what you would think. Though it is big it is not grand, and there is a large tree in front that takes the view. A side door is greeted by concrete steps, the cheap sort, and the driveway has been paved. There is a historical marker, but it is small, and so the first thing a young man realizes when he visits the home of Emily Dickinson is that the world is, in fact, not as in love with her as he is. I wanted to gather the leaves, you know, clean up the place. And I was looking all about the house, before making my approach, when I saw this thing that was not her but only in my mind was her, swing open the side door and set a foot quickly on the step. She met my eyes and went white, whiter than she already was, anyway, and like a wind she fled back into the house. The door closed as if it were on a spring. For a second I could not move.

I wrote in my journal that evening:

“I saw Emily Dickinson step out of a screen door and look at me with dark eyes, those endless dark eyes like the mouth of a cave, like pitch night set so lovely twice beneath her furrowed brow, her pale white skin gathering at the red of her lips, her long thin neck coming perfectly from her white dress flowing so gently and clean around her waist, down around her knees then slipping a tickle across her ankles. And then she went back into the house and it scared me to walk around the place.”

Penny says it is when they are in their twenties that people lose their minds. She says this is what happened to her mother. And when we talk about it, I think of myself in Amherst, so confident at the thing I saw, and at once confident there was nothing there because Emily is dead.

I stopped imagining her immediately. I never told anybody about this because nothing like this happened anymore, so there was no need, and what’s more I couldn’t bear to find out that I was going crazy, that I was indeed seeing things. I blamed it on loneliness of the biochemical sort. When a person has no other persons he invents them because he was not designed to be alone, because it isn’t good for a person to be alone.

There once was a man named

Don Astronaut.

Don Astronaut lived on

a space station out in space.

Don Astronaut had

a special space suit that kept

him alive without food or

water or oxygen.

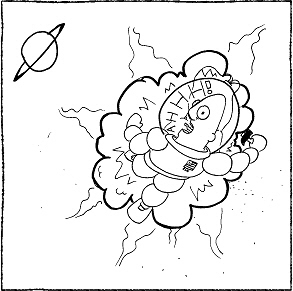

One day there was an accident.

And Don Astronaut was

cast out into space.

Don Astronaut orbited the earth

and was very scared.

Until he remembered his special

suit that kept him alive.

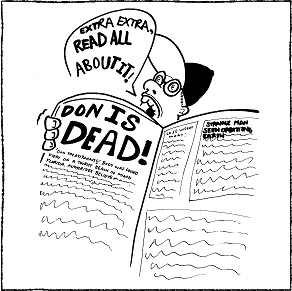

But nobody’s government came

to rescue Don Astronaut because

it would cost too much money.

(There was a conspiracy, and they

said he had died, but he hadn’t.)

So Don Astronaut

orbited the earth again

and again, fourteen

times each day.

And Don Astronaut orbited

the earth for months.

And Don Astronaut orbited

the earth for decades.

And Don Astronaut orbited the earth

for fifty-three years before he died a

very lonely and crazy man—just a shell of

a thing with hardly a spark for a soul.

One of my new housemates, Stacy, wants to write a story about an astronaut. In his story the astronaut is wearing a suit that keeps him alive by recycling his fluids. In the story the astronaut is working on a space station when an accident takes place, and he is cast into space to orbit the earth, to spend the rest of his life circling the globe. Stacy says this story is how he imagines hell, a place where a person is completely alone, without others and without God. After Stacy told me about his story, I kept seeing it in my mind. I thought about it before I went to sleep at night. I imagined myself looking out my little bubble helmet at blue earth, reaching toward it, closing it between my puffy white space-suit fingers, wondering if my friends were still there. In my imagination I would call to them, yell for them, but the sound would only come back loud within my helmet. Through the years my hair would grow long in my helmet and gather around my forehead and fall across my eyes. Because of my helmet I would not be able to touch my face with my hands to move my hair out of my eyes, so my view of earth, slowly, over the first two years, would dim to only a thin light through a curtain of thatch and beard.

I would lay there in bed thinking about Stacy’s story, putting myself out there in the black. And there came a time, in space, when I could not tell whether I was awake or asleep. All my thoughts mingled together because I had no people to remind me what was real and what was not real. I would punch myself in the side to feel pain, and this way I could be relatively sure I was not dreaming. Within ten years I was beginning to breathe heavy through my hair and my beard as they were pressing tough against my face and had begun to curl into my mouth and up my nose. In space, I forgot that I was human. I did not know whether I was a ghost or an apparition or a demon thing.

After I thought about Stacy’s story, I lay there in bed and wanted to be touched, wanted to be talked to. I had the terrifying thought that something like that might happen to me. I thought it was just a terrible story, a painful and ugly story. Stacy had delivered as accurate a description of a hell as could be calculated. And what is sad, what is very sad, is that we are proud people, and because we have sensitive egos and so many of us live our lives in front of our televisions, not having to deal with real people who might hurt us or offend us, we float along on our couches like astronauts moving aimlessly through the Milky Way, hardly interacting with other human beings at all.

Stacy’s story frightened me badly so I called Penny. Penny is who I call when I am thinking too much. She knows about this sort of thing. It was late, but I asked her if I could come over. She said yes. I took the bus from Laurelhurst, and there were only a few people on the bus, and none of them were talking to each other. When I got to Reed, Penny greeted me with a hug and a kiss on the cheek. We hung out in her room for a while and made small talk. It was so nice to hear another human voice. She had a picture of her father on her desk, tall and thin and wearing a cowboy hat. She told me about her father and how, when she was a child, she and her sister Posie spent a year sailing in the Pacific. She said they were very close. I listened so hard because it felt like, while she was telling me stories, she was massaging my soul, letting me know I was not alone, that I will never have to be alone, that there are friends and family and churches and coffee shops. I was not going to be cast into space.

We left the dorms and walked across Blue Bridge, a beautiful walking bridge on the campus at Reed that stretches across a canyon, fit with blue lights, which, when you look at them with blurred eyes, feels like stars lighting a path winding toward heaven. The air was very cold, but Penny and I sat outside commons and smoked pipes, and she asked me about my family and asked me what I dreamed and asked me how I felt about God.

Loneliness is something that happens to us, but I think it is something we can move ourselves out of. I think a person who is lonely should dig into a community, give himself to a community, humble himself before his friends, initiate community, teach people to care for each other, love each other. Jesus does not want us floating through space or sitting in front of our televisions. Jesus wants us interacting, eating together, laughing together, praying together. Loneliness is something that came with the fall.

If loving other people is a bit of heaven then certainly isolation is a bit of hell, and to that degree, here on earth, we decide in which state we would like to live.

Rick told me, a little later, I should be living in community. He said I should have people around bugging me and getting under my skin because without people I could not grow—I could not grow in God, and I could not grow as a human. We are born into families, he said, and we are needy at first as children because God wants us together, living among one another, not hiding ourselves under logs like fungus. You are not a fungus, he told me, you are a human, and you need other people in your life in order to be healthy.

Rick told me there was a group of guys at the church looking to get a house, looking to live in community. He told me I should consider joining them.