2

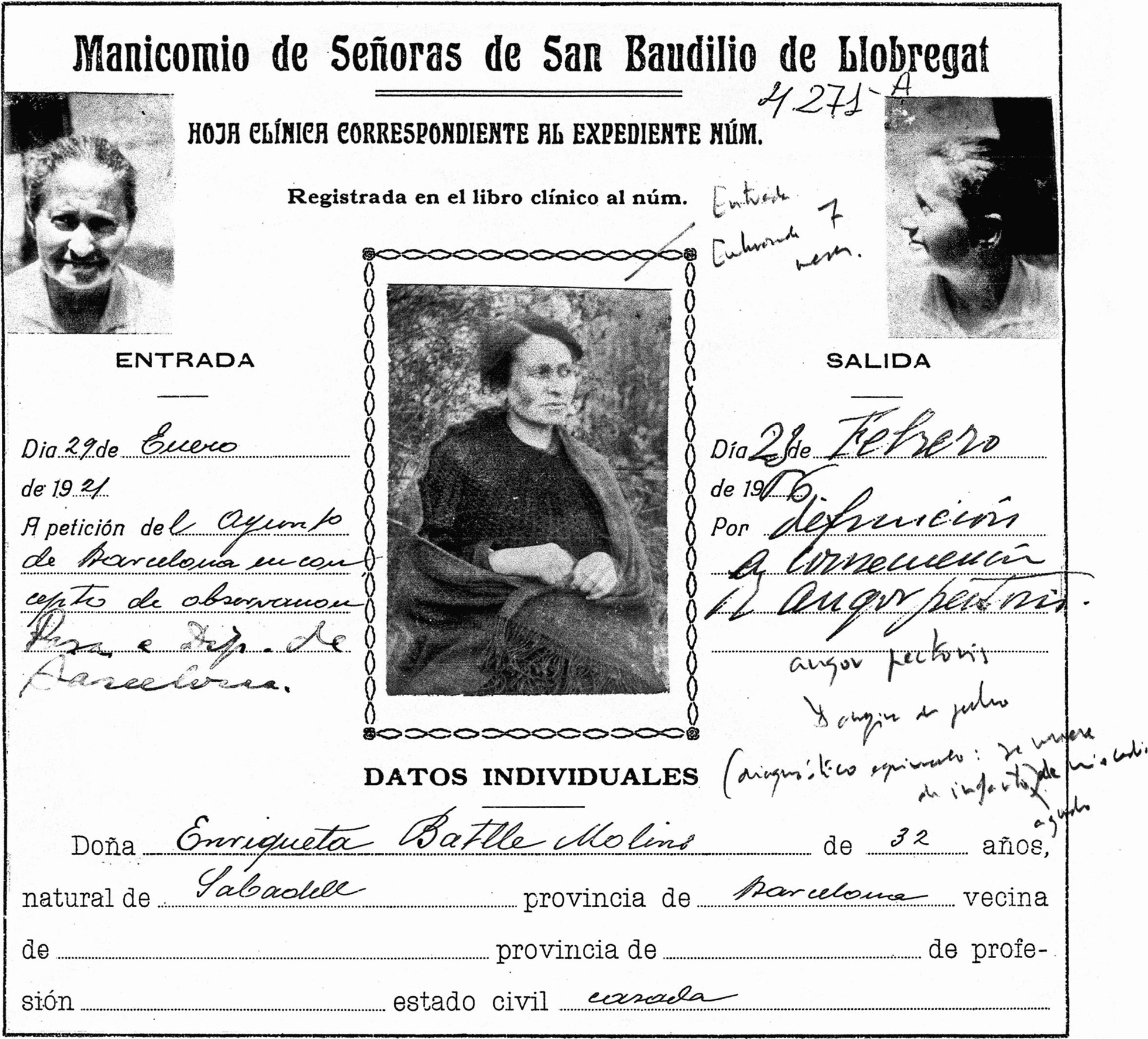

His mother was insane. Her name was Enriqueta Batlle Molins and, although Marco always believed that she had been born in Breda, a quiet little village in the Montseny massif, in fact she was from Sabadell, an industrial city near Barcelona. On January 29, 1921, she was admitted to the Sant Boi de Llobregat insane asylum for women. According to the asylum records, this was three months after she had separated from her husband, who had abused her; during this period, according to the records, she earned her living going from house to house doing domestic work.

She was thirty-two years old and six months pregnant. When the doctors examined her, she seemed confused, she contradicted herself, and she was plagued by paranoid thoughts; her initial diagnosis read: “Persecution mania with degenerative symptoms”; in 1930 this was changed to “dementia praecox”: what nowadays we know as schizophrenia. On the first page of the dossier there is a photograph of her, possibly taken on the day she was admitted. It shows a woman with long, straight hair and strongly marked features, a generous mouth and pronounced cheekbones; her dark eyes are not looking at the camera, but everything about her radiates the dark, melancholy beauty of a tragic heroine; she is wearing a knitted black cardigan, and her back, her shoulders and her lap are covered with a shawl that she gathers into her hands over her belly, as though she were trying to conceal her inconcealable pregnancy, or trying to protect her unborn child. This woman does not know that she will never again see the outside world that has abandoned her to her fate, locking her away and leaving her to become utterly engulfed by her madness.

There is no less dramatic way to say it. In the thirty-five years that Marco’s mother spent in the asylum, the doctors examined her only twenty-five times (typically once a year, but after her initial admission, eight years went by without her being examined), and the only treatment they prescribed consisted of forcing her to work in the laundry, “with excellent results,” according to a note from one of the doctors treating her. There are many such notes; though not all are as cynical, all are curt, vague and heartbreaking. In the beginning they record that the patient is in good physical condition, but they also record her self-centredness, her hallucinations (particularly auditory hallucinations), her sporadic violent outbursts; later, her deterioration gradually affects her physically, and by the late 1940s the notes describe a woman who is bedridden and has completely lost all sense of direction, her memory and any sign of her own identity; she is reduced to a catatonic state. She died on February 23, 1956, as a result of “angor pectoris,” according to her file. Even this diagnosis was inaccurate: no-one dies of chest pain; it is likely that she died of a heart attack.

Marco’s mother gave birth to him in the asylum, on April 14, according to him; this is the date that appears on his identity card and his passport. But it is false: Marco’s fiction begins here, on the very day he came into the world. In fact, according to his mother’s case file and his own birth certificate, Marco was born on April 12, two days earlier than the date he would claim. Why lie then, why change the date? The answer is simple: because, after a certain point in his life, this allowed him to begin his talks, his speeches and his living history classes with the words “My name is Enric Marco, and I was born on April 14, 1921, exactly ten years before the declaration of the Second Spanish Republic,” which in turn made it possible for him to present himself, implicitly or explicitly, as a man of destiny who has witnessed first hand the major historical events of the century and encountered its principal protagonists, as an emblem, a symbol or the very personification of his country; after all, his personal biography was a mirror image of the collective biography of Spain. Marco claims that the purpose of his lie was merely didactic; it is difficult, however, not to see it as an ironic wink at the world, as a blatant way of implying that, since his date of birth coincided with a momentous day in the history of his country, the heavens or the fates were signalling that this man was destined to play a decisive role in that history.

From the dossier in Sant Boi asylum, we know one more thing: on the day after he was born, Marco’s mother watched as her son was forcefully taken from her and given to her husband, the man she had fled from because he abused her, or because she said that he abused her. Did Marco ever see his mother again? He claims he did. He says one of his father’s sisters, his aunt Catherine—who breastfed him, since she had lost a child a few short weeks before he was born—took him to see his mother once or twice a year when he was a boy. He says that he clearly remembers these visits. He says that he and Aunt Catherine would wait in a huge bare white-walled room with the families of other patients for his mother to appear. He says that after a while his mother would emerge from the laundry rooms wearing a blue-and-white-striped apron, her eyes staring vacantly. He says that he would give her a kiss, but that she never kissed him back, and that in general she did not address a word to him, to his aunt Catherine, to anyone. He says that she often talked to herself, and that she almost always talked about him as though he were not there in front of her, as though she had lost him. He says that he remembers at the age of about ten or eleven, his aunt Catherine pointing to him and saying to his mother: “See what a handsome lad you have, Enriqueta: he’s named Enrique, after you.” And he says he remembers his mother fiercely wringing her hands and saying: “Yes, yes, he is a handsome lad, but he is not my son”; and, pointing to a two-year-old boy scampering around the room, he says she added: “my son looks like him.” He also says that at the time he didn’t understand, but that in time he realized his mother said this because her only memory of him was when he was no more than two or three years old, when she still had a vestige of lucidity. He says that he would sometimes bring her food in a lunch box and that sometimes he managed to exchange a word or two with her. He says that one day, after eating what he had brought in the lunch box, his mother told him that she worked hard in the laundry, that it was gruelling work but she didn’t care, because they had told her if she worked hard, they would give her back her son. He says he doesn’t remember when he stopped going to visit his mother. He says it was probably when his aunt and uncle stopped bringing him, perhaps when he reached adolescence, by which time the Civil War had already begun, perhaps earlier. In any event, he says, after that, he never again visited her, never again felt the slightest desire to see her, never worried about her—he forgot her completely. (This is not entirely true: many years later, Marco’s first wife told her daughter Anna María that she persuaded Marco to go and see his mother at the asylum after they were married; she also told her that they visited once or twice, and that all she remembered of these visits was the woman smelled strongly of bleach and did not recognise her son.) He tells me that he knows his mother died in the mid-1950s, but cannot even remember attending her funeral. He tells me that he cannot understand how he could have left her in an asylum for more than thirty years, how he could have left her to die alone, although he adds that there are many things from that period he doesn’t understand. He says he thinks about his mother often now, that he dreams of her sometimes.