Why does it rain?

It rains because warm air can hold more water than cool air; when wet air cools down, it can no longer hold as much water, so the water condenses and falls to the earth as rain, snow, or hail.

Temperatures fall as altitude increases, so warm, wet air cools down as it rises. Warm air is less dense than cool air, so warm air will tend to rise on its own. It can also be forced upward by terrain or by another air mass. Each of these scenarios leads to a different type of rain.

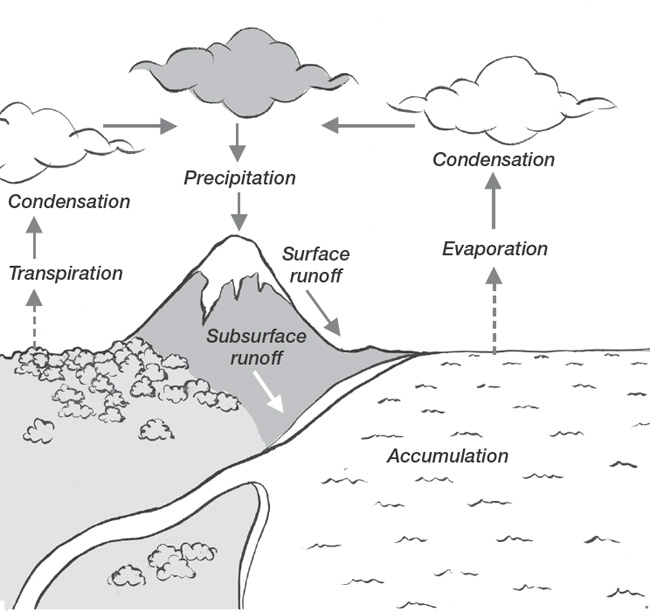

When water evaporates from a puddle of water, some of the water molecules in the puddle will be moving about as fast as if they were at boiling point, and some of these will escape from the puddle and into the air as water vapor. The air can only hold so much of this water vapor; once it reaches its limit, the extra water will condense into visible droplets, forming clouds or fog, and some of these droplets will fall as precipitation or rain.

The amount of vapor the air can hold depends on temperature. Warmer air can hold more vapor, but because it is not as dense as cool air, it will tend to rise. The atmosphere cools by about 44°F for every 3,000 feet you rise. As the warm, wet air rises, it also cools demonstrably, and above a certain point, water vapor condenses into droplets.

Not all rains are exactly the same

Convective rain falls when pockets of warm, wet air rise because they are less dense than the surrounding, cooler air. This occurs when the ground is heated by direct sunlight on a warm day. Warm, wet air can also be forced up as it passes over mountains, causing orographic rain, or it can be forced up when it runs into a mass of cold air. The warm and cold air masses don’t mix; instead, the warmer one is forced up and over the denser, colder air, creating a weather front, which leads to frontal rain. A typical weather front consists of a billion tons of warm air overlaying more than 800 million tons of colder air.

The clouds that form as a result can be enormous: A typical cumulus cloud (the individual fluffy cloud that might be seen floating around on a mostly sunny day) weighs just over 1.1 million pounds, equivalent to about 100 elephants. That’s enough water to fill 7 average-sized backyard swimming pools. A storm cloud, on the other hand, can hold over a million tons of water.

Compared to the water in the oceans and ice caps, and even to the water in rivers and lakes, the amount of water in the atmosphere is relatively small—if the water in the atmosphere fell as rain all at once, the oceans would only get around an inch deeper. But try telling that to the people who live in Mawsynram, India, probably the wettest place in the world, where the average annual rainfall is about 468 inches, or to the inhabitants of Waialeale in Hawaii, which has an average of 335 rainy days a year. They probably long to visit Arica, Chile, which boasts 1 day of rain every 6 years.

The water cycle