The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries saw a major shift in the power balance in East Asia as a new military power emerged. Up until the midnineteenth century East Asia had been dominated for centuries by the Chinese Qing empire. Although China had suffered periods of decline over the years, no regional power existed that could challenge the Qing empire’s supremacy. This all changed in the mid-nineteenth century when the historically isolated Japanese empire reluctantly began to open up its ports to Western traders. Many traditionalists in Japan were hostile to this trade and the resultant Western influence over the empire. Regardless of the complaints of traditionalists, a period of unprecedented modernization took place over just a few decades which created, at least on the surface, a forward-looking nation. Over the next forty years Japan rapidly developed from a traditional, almost medieval nation to a modern, ambitious state with an up-to-date army and navy. Some of the old military class chose to ignore this process, while others realized that this was the only way to stop European exploitation. The Meiji emperor actively encouraged his army to import the latest rifles, artillery and ships so that it could defend itself against any European military aggression. He saw what had happened to Imperial China following their defeat in the Opium Wars (1839–60). After China opened its ports to Western traders military force was used to compel the Chinese to buy Western goods, including opium.

This new Japan soon began to look to expand its influence onto mainland Asia and by 1894 was ready to challenge the ramshackle Chinese empire militarily. That year a dispute over control of supposedly independent Korea led to a full-scale war between the two powers, known as the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–5). Fought both in Korea and Manchuria, on land and at sea, the war was a disaster for the Chinese and ended with Japan’s complete victory. This left China open to further foreign exploitation as the European powers demanded trade concessions from the Qing emperor. A deeply humiliated Chinese empire was now forced to consider modernizing in preparation for inevitable further clashes with Japan.

Over the next sixteen years the empire faced further ignominy following the Boxer Rebellion of 1900 and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–5. The latter conflict saw China and its Manchurian provinces used as a battleground by the combatants. At the end of the war victorious Japan was now the undisputed power in Asia and, having taken over Russia’s territorial concessions in Manchuria, was now prone to dominating China. In 1911 the corrupt and inept Qing dynasty was finally overthrown and the emperor was replaced by a Chinese Republic which soon descended into chaos. The next seventeen years in Chinese history is known as the ‘warlord era’ when local military governors, or ‘warlords’, fought each other. The warlords ignored a series of weak civil governments in Peking and pursued their own power struggle, forming and breaking alliances throughout the 1910s and 1920s. Some warlords accepted Japanese military assistance as the latter hoped to exercise influence over whatever military group came to dominate China.

In the early 1920s a nationalist revolutionary party, the Kuomintang, began a campaign to reunite China under one government. Formed by a long-term revolutionary, Sun Yat-sen, the Kuomintang was taken over on his death in 1925 by the party’s military leader, Chiang Kai-shek. Chiang and his National Revolutionary Army (NRA) triumphed in a two-year crusade known as the Northern Expedition. By 1928 the Northern Expedition had succeeded in defeating all of the warlords, either in battle or by negotiation. Chiang and his NRA had finally beaten their enemies and formed a Nationalist government, with its new capital in the city of Nanking. Their victory was short-lived as Chiang’s leadership was never fully accepted by his rivals within the Nationalist camp. Fighting between these various factions in 1929 and 1930 ended again with victory for Chiang Kai-shek in the so-called ‘Great Plains War’. Again, Chiang’s success did not endure as the Japanese had been preparing to challenge the new Nationalist government of China. Japanese troops stationed in northern China had already clashed with NRA troops in 1928. For the first time Chiang had backed down when faced by Japanese garrisons that would not be moved from the concessions that had been granted to them in 1900.

In 1931 the Japanese finally struck when their troops stationed in parts of the three Chinese provinces of Manchuria staged an ‘incident’. The ‘Mukden Incident’ saw fighting between Japanese and Chinese units in southern Manchuria in September 1931. The Japanese took over the city of Mukden and then gained ground into the rest of Manchuria, facing little resistance. Chiang Kai-shek had instructed his commanders in Manchuria to withdraw in front of the Japanese advance. This was in order that the world would see the Japanese as the aggressor and China as the victim. International outrage at Japan’s actions did not worry them, however, and by mid-1932 they had taken most of Manchuria, setting up a client state called Manchukuo. A well-organized Chinese boycott of Japanese goods in retaliation for their invasion of Manchuria badly hurt the Japanese economy. When some Japanese residents in Shanghai, the main trading city in China, were attacked by Chinese rioters the Japanese military struck again. Japanese marines were landed in the city in late January 1932 and fighting with the local Chinese troops continued until May. The fighting ended with a peace treaty but before long Japan’s territorial ambitions were to result in further conflict.

In 1933 the Japanese took over the Chinese province of Jehol, which bordered their newly conquered client state Manchukuo. Japan was not worried by the disapproval of the League of Nations and they began their invasion of Jehol in late February 1933. The action was followed on 27 March by their withdrawal from the League of Nations. Japan had simply claimed that Jehol was historically part of Manchuria and therefore should be included in the territory of Manchukuo. Resistance to the Japanese invasion was poorly organized and the ease of their victory led the Imperial army to plan further acts of aggression. The Japanese moved troops southwards into northern China and although the Chinese fought hard, the Japanese advanced to the gates of Peking. Again, a peace treaty was signed in May 1933 with the Japanese demanding the demilitarization of Chinese territory south of the Great Wall. They insisted that the Great Wall should form the boundary between Manchukuo and northern China and the demilitarized zone would avoid further clashes. Once more the Chinese had to concede territory and other rights to the Japanese, who threatened more aggression unless Chiang Kai-shek’s government agreed to their terms. Chiang Kai-shek was obsessed with his campaign to defeat his Chinese Communist enemies and saw the loss of some territory in far-off northern China as temporary.

Over the next few years the Japanese and their secret service made further incursions, both militarily and politically, into northern China. During the last few years before the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War the Japanese constantly looked for weak spots in the Nationalist government’s hold on northern China. They formed several short-lived local governments within the demilitarized zone and in the remote Chinese provinces of Chahar and Suiyuan. Between 1935 and 1937 fighting also took place in the outlying Chinese province of Suiyuan when ‘proxy’ Inner Mongolian forces attacked several towns. The poorly trained Inner Mongolians were supplied with Japanese arms and undercover Imperial army officers advised the rebels. Japanese troops in Mongolian uniforms also operated tanks and artillery donated to the Inner Mongolians, while pilots flew a handful of planes for them. Although the Mongolians were surprisingly beaten by the local Chinese troops, their withdrawal was temporary and they returned at the start of the Sino-Japanese War.

The Nationalist army that prepared to meet any further aggression by the Japanese in 1937 was a large force of approximately 1,700,000 regulars and 518,400 reservists. It was almost entirely an infantry force with only one or two mechanized units equipped with a few tanks and armoured cars. Artillery was in short supply with most guns being leftovers from the 1920s and only a few dozen modern guns imported from Germany, Sweden and other European countries. Loyalty to the central government of Chiang Kai-shek amongst large sections of the army was questionable with only 380,000 troops described as being 100 per cent loyal. A further 520,000 troops belonged to units which although ‘traditionally loyal to Chiang’, could not be totally counted on. The rest of the army was a mixture of units loyal first and foremost to their commander or units that were ‘politically’ doubtful.

A typical, exotic-looking Chinese Nationalist soldier fighting the Japanese in Manchuria in 1932 is pictured before going out on patrol. His sheepskin hat and padded uniform are well adapted to the severe weather of the 1931–2 fighting. With a MP-28 sub-machine gun over his shoulder, he looks resolute enough but the odds were against the Chinese defenders. A lack of any real support from the government in far-off Nanking meant that the struggle against the Japanese was in the end futile.

A Japanese Imperial army mountain gun fires towards positions held by Chinese troops in the northern Chinese province of Manchuria in 1931. The Japanese had been gradually increasing their influence in Manchuria since their victory over the Chinese in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–5). In 1931 they made their first major land grab of Chinese territory with the invasion of Manchuria. Within a few months they had set up a client state called Manchukuo which they effectively ruled through a puppet emperor until August 1945.

Japanese troops guard one of the Nationalist armoured trains captured during fighting in Manchuria between 1931 and 1933. The fleet of armoured trains in Manchuria belonged to the Nationalist North-Eastern Army of Chang Hsueh-liang. Most of the captured trains were repaired by the Japanese and used on the open plains of Manchuria and northern China until August 1945.

Chiang Kai-shek, the ‘Generalissimo’ of Nationalist China, ruled the country from the late 1920s. He had faced opposition from the Chinese Communists since he took power and open aggression from the Japanese empire since 1931. When full-scale war broke out between China and Japan in 1937 Chiang proved a stubborn leader. He was not willing to surrender to the Japanese even in the face of heavy defeats or to come to terms with them as they expected.

In a pre-war manoeuvre a Chinese Nationalist Vickers 6-ton light tank armed with a 37mm Puteaux gun moves along a road. Modern armoured vehicles like this were imported by the Chinese in the 1930s but never in sufficient numbers to form large mechanized units. The Nationalists suffered from a confused purchase policy which saw several types of tank imported.

Nationalist artillerymen practise with rangefinders during training in the year before the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War. The more successful Nationalist units received the best weaponry and equipment leading to a sharp contrast between the best and worst Chinese divisions in 1937.

Soldiers of the Nationalist army on parade to celebrate the fiftieth birthday of their leader Chiang Kai-shek on 30 October 1936. They are parading in the southern city of Canton which Chiang was visiting for the first time in ten years. Canton had been the original base of the Kuomintang Party and its Nationalist army which defeated the Chinese warlords between 1926 and 1928. Men on the right of the parade are armed with Daido fighting swords worn in scabbards on their backs.

By 1936, when this photograph was taken, Chiang Kai-shek was supposedly the undisputed leader of Nationalist China. He is seen in discussions with General Lung Yun, the ‘wily’ governor of Yunnan from 1927 who ran his province more or less as his own fiefdom. Lung’s loyalty to Chiang was always uncertain and the Nationalist leader could never really trust him. Unfortunately for Chiang, there were many of his generals and their troops, especially in the outlying provinces of China, whose support was questionable.

General Pai Chung-hsi, the leader of the Nationalist troops in Kwangsi province and one of the commanders who proclaimed his intention to fight against the Japanese in 1936. Many of the independently minded Nationalist commanders ran their provinces in the same way as they had in the warlord era of the 1920s. Pai had rebelled against Chiang Kai-shek several times in the 1930s and although allowed back into the Nationalist fold, had little loyalty to his leader. He was one of the generals who were frustrated at the Nationalist leader’s perceived ‘appeasement’ of the Japanese from 1931 to 1937.

Massed ranks of Nationalist Chinese troops march past the review stand in a show of force by Chiang Kai-shek’s government in 1936. The Chinese were never short of manpower and in most cases the Nationalists could at least arm their men with rifles and basic equipment. It was when it came to modern heavy weaponry that the Chinese army revealed weaknesses that were not going to be corrected by 1937. These troops were just as likely to be fighting Communist or other rebellious elements within China as the Japanese.

After the formation of the ‘United Front’ between sworn enemies the Communists and Nationalists, these Red Army troops in Shensi march off to join the Nationalist army in September 1937. In theory the uneasy alliance would hold as long as China was threatened by the Japanese invader. In reality an undeclared civil war existed almost from day one between Chiang Kai-shek’s and Mao Tse-tung’s followers. The banner flown behind the Communist volunteers proclaims their support for the Republicans fighting their own civil war in Spain.

Two of the most prominent Chinese Communist leaders are pictured at their Yenan headquarters in the aftermath of the Long March of 1934–5. Mao Tse-tung, the leader of the party, had finally managed to consolidate his position at the head of the Communists during the Long March. Chou En-lai, in the cap, was the Political Director of the Red Army and was the main negotiator in talks with Chiang Kai-shek. His diplomatic skills when dealing with the Nationalists led to the United Front agreement to fight the Japanese in early 1937.

Communist machine-gunners are seen training with their Browning heavy machine gun before the war. These men belong to one of the better Communist guerrilla units which fought the Japanese after 1937. The civil war between the Nationalist government and the Communists weakened the Chinese ability to resist Japanese incursions into their territory. In the accompanying caption to this photograph its states that the average age of a Communist soldier was 19 in 1936.

Japanese youth volunteers assembled near Tokyo in the 1930s serve to demonstrate the empire’s total preparation for war. The boys’ headgear shows that they belonged to several organizations, all of which were designed to prepare them for military service. Japan was like Nazi Germany, a militarized state with military style uniforms worn by school children, students and many workers.

Like their male compatriots, the women and girls of Imperial Japan were brought up from birth to be prepared to serve their nation. The girls in the foreground belong to the Showa Association, the main patriotic organization in Japan in the 1930s. Public support in Japan for the war in China was almost total and the young girls and women of the empire played their part. Although their role in Japanese society was generally subservient, they were expected to fulfil many male roles when war began.

In this pre-war photograph the crew of a camouflaged Japanese Imperial army Type 95 75mm field gun prepare to fire their weapon. Based on the French Schneider Mle 1931, this gun was first made in 1935 and was intended to replace the Type 41, which dated from 1908. The crew are taking part in a large-scale manoeuvre and wear white hat bands as a field sign to distinguish the competing armies.

Soldiers of the Japanese Imperial Guard march through Tokyo in a pre-war parade in front of Emperor Hirohito. The Imperial Guard was established in 1871 exclusively from ex-Samurai warriors and remained an ‘elite’ formation. However, it had not fought in action since 1905 and was not to do so until the Pacific Campaign of 1941–2. Most of the Japanese Imperial army was far less concerned with the ‘spit and polish’ of the parade ground and fighting capability was its major concern.

Japanese Emperor Hirohito posing in his full dress uniform for an official portrait in the mid-1930s. The emperor, who had acted as regent since 1922, came to the throne in 1926 and was formally enthroned in 1928. Although worshipped by the Japanese people as a god, in reality his power in modern Japan was largely symbolic. His status is perhaps best explained by saying that Japan was not ruled ‘by’ the Emperor but in the ‘name’ of the Emperor. This symbolic status does not excuse his role in wartime Japan and how much responsibility he had for the war against China and the Allies is open to debate.

Soldiers of the Inner Mongolian Army which fought a ‘proxy’ war against the Nationalist government in Suiyuan province in 1936. Before the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937 the Japanese supported several rebel groups in China that were willing to fight Chiang Kai-shek. The Inner Mongolians were fighting for a separate state in Suiyuan and Chahar provinces and received small arms, artillery and clandestine air support from the Japanese. These same troops were to join the Japanese advance through their region in September 1937 serving as irregular cavalry.

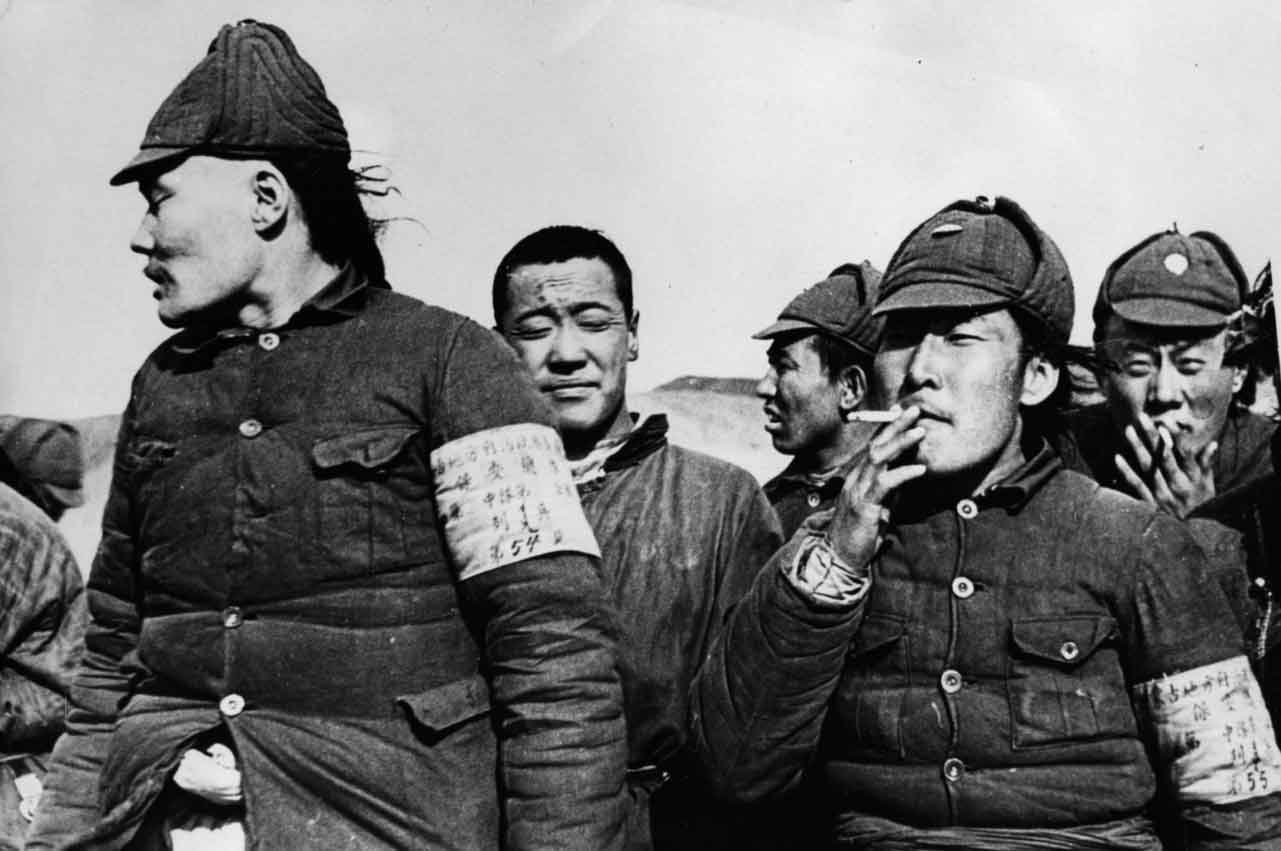

Tough-looking soldiers from northern China pictured during fighting against Mongolian rebels in late 1936. They had fought in an undeclared war between the Nationalist government and the Japanese and their Chinese ‘puppets’ in the remote provinces of Chahar and Suiyuan. Although the Chinese had been largely victorious, they were soon to be overrun by the Japanese when full-scale war broke out.

In the last weeks before the outbreak of full-scale war between China and Japan in July 1937 a civil defence drill takes place in the city of Hankow. As the fear of a Japanese invasion of China increased more and more air raids and other drills took place. The Kuomintang Party organized its members into various first-aid, air-raid patrol and firefighting forces in preparation for the coming conflict.

A Nationalist mountain howitzer being used in a pre-war manoeuvre with the crew sheltering underneath camouflage netting. The gun is an imported Swedish Bofors 75mm M1930 model, one of the few modern types used by the Nationalist army at the start of the war. There were never enough artillery pieces in the Chinese army and most guns were kept under the strict control of commanding officers. One of the Nationalists’ greatest weaknesses was their fear of losing precious weaponry in battle. For this reason some guns were kept at divisional headquarters instead of at the front line where they were needed.

This Nationalist propaganda poster of the Sino-Japanese War has the ‘brave’ and athletic Chinese soldier killing the ‘cowardly’ and animal like smaller Japanese soldier who cowers in fear. Racial stereotypes were used widely by both sides in this brutal war with the intention of de-humanizing the enemy.