Japan Triumphant, 1939–42

After two years of hard fighting and a series of unbroken defeats the Chinese Nationalist government was totally demoralized by the end of 1938. The dawn of 1939 brought no respite for the Nationalists and in February Hainan Island, off the coast of southern China, fell to the Japanese. The Japanese wanted Hainan to use as a base for the bombing of China’s southern provinces and to reinforce its naval blockade. Japan hoped that by stopping supplies getting into China the Nationalist government would finally come to a settlement. Nationalist guerrilla forces withdrew to the centre of the island where they met the strong Communist guerrilla force based there. In late April, Nanchang, the capital of Kiangsi province, fell to the Japanese, who had been attacking the city since mid-March. The city, defended by a 200,000-strong garrison, was surrounded by a 120,000-strong Japanese army.

At the end of 1939 the Nationalists hopefully launched their large but poorly organized winter offensive against the Japanese. Chiang had managed to gather a large force for this campagin, using 550,000 front-line troops and guerrilla forces. The offensive was spread across nine provinces and lasted for much of the 1939–40 winter before petering out in February 1940. Although the Nationalists did make some progress at a heavy cost, the winter offensive was ultimately a failure as they could not hope to hold on to what they had gained. With a shortage of artillery and other heavy weaponry on the Nationalist side, any units that did gain ground were soon bombarded into submission by superior Japanese artillery. Most of what little heavy equipment and weaponry the Chinese had was lost in the fighting and with thousands of newly trained troops killed Chiang Kai-shek knew his forces were shattered. At the end of the offensive in early 1940 Chiang determined that from now onwards any Nationalist offensives in China would be purely regional with nothing approaching the scale of the 1939–40 offensive. Although Chiang tried to keep his generals’ morale up by talk of future attacks against the Japanese, he privately admitted that his army was no longer up to the task.

It was in fact the Communists who launched the next large-scale offensive against the Japanese between August and December 1940, although the main fighting ended in September. The so-called Hundred Regiments Campaign was aimed at the Japanese army in northern China and involved 115 regiments of the Eighth Route Army. In 1940 the Eighth Route was still officially a unit within the Nationalist army but received its orders from Mao Tse-tung rather than Chiang Kai-shek. With a total of 400,000 regulars and guerrillas, the Communist forces involved looked impressive on paper but the men taking part were poorly armed. Communist forces attacked railways and roads and targeted isolated Japanese strongpoints and forts. Fighting was heavy and the Japanese and their ‘turn-coat’ or ‘puppet’ Chinese troops who fought for them were defeated on several occasions by the Communists. Despite some successes, the offensive died out for the same reasons as the Nationalists had failed. The end of the campaign was followed by a Japanese counter-offensive which brutally punished the civilian population who had supported the Communists.

Another result of the Communist offensive was the heavy Japanese attacks on the Nationalist army which had not taken part. This led to resentment by the Nationalist command who were unhappy with the independent stance taken by the Eighth Route Army. The discord between the Nationalists and Communists resulted in the end of their uneasy alliance. The United Front alliance of 1937 saw an agreement for co-operation between the Nationalist government and the Communists. It included Communist units serving under Nationalist army command until the Japanese were defeated. In an incident in January 1941 the 15,000-strong New Fourth Army, one of the two main Communist formations serving in the Chinese army, clashed with Nationalists, which resulted in the deaths of up to 5,000 Communists. Any hope of future co-operation against the Japanese was now over and the Nationalists spent the rest of the war blockading the Communists in their Shensi base. Chiang ordered the official disbandment of the New Fourth and for the rest of the war the Nationalists and Communists fought their own independent campaigns against the Japanese.

The fighting continued throughout 1941. In May the battle switched to southern Shansi province and ended in yet another withdrawal of Nationalist forces after heavy fighting. In September there was a second attempt by the Japanese to take the city of Changsha and again the Chinese managed to push the Imperial army back. In autumn 1941 fighting continued and centred on the strategically important city of Chengchow in Honan province. The city fell to the Japanese on 4 October before being recaptured by the Nationalists on the 31st.

Throughout their war in China the Japanese had consistently ignored any criticism from the West and the USA. After leaving the League of Nations in 1933 the Japanese had carried on as if international condemnation of their aggression had no effect on them whatsoever. Although the USA had stayed neutral when the Second World War broke out in September 1939, its sympathies lay with the beleaguered United Kingdom in 1940. When Japan signed the Tripartite Pact with Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany in September 1940 relations between them and the USA deteriorated. Trade embargoes were introduced by the USA and these had a detrimental effect on the already weak Japanese economy. The embargoes gradually impacted on 75 per cent of Japanese trade and targeted ‘strategic materials’ vital to resource Japan. During 1941 the USA had also begun to establish firm links with Chiang Kai-shek as the threat of war with Japan gathered pace. In August the USA introduced an effective embargo on oil exports to Japan, which if enforced meant that conflict with the Japanese empire was inevitable. Also in 1941, the British were threatened by Japanese aggression in their possessions in South-East Asia and the USA sent military missions to Chungking. Despite attempts at negotiation, the Japanese were unwilling to withdraw from China and when on 7 December 1941 the Japanese launched their attack on the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor Nationalist China’s single-handed fight against the Japanese empire was at an end. From now on the Sino-Japanese War was to become a ‘war within a conflict’, a sideshow of the Second World War. However, if Chiang Kai-shek expected to receive large amounts of military and other support from the Allied Powers he was to be disappointed as they had enough problems of their own for the time being.

Hainan, the large island off the southern coast of China, was invaded by a Japanese expeditionary force in February 1939. The Japanese amphibious force that landed in the north of the island was part of the same army that had taken Canton the previous October. Although the Nationalist garrison was quickly defeated, a large Communist guerrilla force in the interior of the island was to prove a problem for the occupying troops. Here a sentry stood on a rooftop looks out over one of the towns on Hainan a month after its occupation began.

A Nationalist machine-gun crew have set up their Czechoslovakian-made ZB 53 heavy machine gun in an anti-aircraft role in Hunan province in 1939. Throughout 1939 the Japanese launched offensives in Hunan aimed mainly at the provincial capital of Changsha. General Chang Fa-kwei, the Nationalist commander of forces in Hunan, complained that his struggle with the Japanese was being ignored by Chiang Kai-shek.

A Japanese Imperial army Type 94 ‘Te-Ke’ tankette stops while on patrol in the street of a recently occupied Chinese city. Its crewmen are sat atop their light tank viewing the local population warily with Nambu Type 14 automatic pistols at the ready. Armed only with a machine gun in its turret, the Type 94 could not be described as a battle tank and was designed as an infantry support vehicle. Having just been in action, the crew have fixed foliage to the body of the tank which has a Japanese flag painted on the front.

The crew of a Japanese Imperial army Sumida M2593 armoured car, which has been fitted with rail wheels, salute troops guarding the line in 1939. These adapted armoured cars were used for patrolling the railways which connected the guard posts and forts built to protect the lines. As well as the six-man crew, other Japanese troops are sitting on top of the car where they are vulnerable to enemy fire.

Relatively smartly uniformed Nationalist soldiers of a headquarters guard pose proudly outside their base in 1939. The officer and his men have all been issued with rarely seen double-breasted winter overcoats. Most Chinese soldiers wore a padded cotton tunic and trousers in the winter campaigns. Nationalist soldiers also wore the Japanese winter coat whenever they took these from captured stores or from the dead bodies of their enemy.

A hastily raised Nationalist militia unit parades in Kwangtung province before going into action in 1939. The men and women who make up this unit are armed, equipped and dressed with an exotic mix of military and civilian items. Headgear includes a few M1 steel helmets, trilbies and workmen’s caps, while only one man has a military tunic. Although a few men have rifles, others are ‘armed’ with nothing more deadly than a wooden stave and a bugle.

This squad with Type 97 81mm mortars prepares to lay down covering fire for an infantry assault in winter fighting. The Type 97 was the most modern type of mortar in service with the Japanese Imperial army and was used alongside the Type 11, introduced in 1922. All the Japanese soldiers wear typical winter gear with a lambswool hat worn underneath their M32 helmets.

Nationalist guerrillas operating just to the north of Hong Kong while the Colony was still held by its British garrison, 1940. A year later the fall of the city meant that any clandestine support that the Chinese received from the residents of Hong Kong was lost to the guerrillas. Men like this could not expect much in the way of support from their leadership in far-off Chungking.

Nationalist militia raised in Kwangtung province listen to a speech by a Kuomintang official in March 1940. At first sight the men look like typical irregular guerrillas but their officially issued overalls and arm badges show they belong to a ‘regular’ formation. They are armed with older versions of the Mauser rifle with the odd ZB-26 light machine gun visible in the crowd. It appears that some of the men at the back of the group have no weapons and would have been armed simply with bamboo spears, the intention being to supply them with rifles when these became available.

During a Japanese anti-guerrilla operation a mixed unit of light tanks and infantry deploy in winter 1941. The infantry wear a hooded winter coat over the top of their regular woollen uniforms. Captured weapons were employed by the Japanese and the machine-gun squad is armed with an ex-Nationalist ZB-26 light machine gun. Armoured support is provided by the three Type 94 light tanks, the machine guns of which will provide covering fire.

A battery of Japanese 105mm Type 92 field guns fires towards Nationalist Chinese positions in 1941. As the war in China progressed the role of the Japanese artillery changed as it was used more and more to suppress guerrilla activity from long range. They rarely faced counter bombardment from Nationalist or Communist artillery because of the shortage of guns in Chinese hands.

A Japanese flamethrower operator shoots flames towards the gate of a Nationalist-held city in 1941. That year the Japanese were consolidating their position in northern Kiangsi, southern Shansi and Honan provinces. In the build-up to start of the war in the Pacific the Japanese Imperial army remained on the offensive in China. Bringing the Chinese to battle was now more difficult as they had learnt hard lessons about trying to take the Japanese in set-piece battles. The flamethrower is the Type 93, which remained the standard model in service with the Japanese throughout the war.

This German-supplied PAK 35/36 37mm anti-tank gun, pictured in 1941 in Kiangsi province, is one of the few that survived the military disasters of 1937–41. By this date most of the remaining heavy equipment and weaponry in the Nationalist army was kept in reserve. Nationalist commanders had one eye on a renewal of the civil war with the Communists when modern weaponry would be at a premium.

Soldiers of the Communist New Fourth Army advance in single file past holes dug for mines to be placed in at a later date. The centre hole is for a large mine, while the surrounding four holes are for small trip mines and the whole thing would be covered with foliage ready to use. The New Fourth Army was officially a unit of the Nationalist army following the formation of the United Front of Communists and Nationalists against the Japanese. During the so-called ‘New Fourth Army Incident’ in 1941 armed clashes between Communist and Nationalist units broke the uneasy alliance. From then on any pretence of co-operation between the rival factions ended and both pursued their own war against the Japanese occupiers.

Chinese Nationalist scout cars are seen on parade close to the wartime capital Chungking in early 1941. These Sfz 222 scout cars were sold to China by Germany in the mid-1930s and are amongst a handful to survive the 1937–41 fighting. Armed only with machine guns, these light armoured cars were no match for the Japanese tanks in China. Heavy equipment like this was kept well away from the war fronts by the Nationalists in preparation for post-war fighting with the Communists.

Nationalist troops move a German-supplied PAK 35/36 37mm anti-tank gun into a new position along the Yangtze River in November 1941. This gun is the original wooden, wheeled version rather than the more common rubber tired model. The Nationalists had a total of 124 of this type of anti-tank gun in service at the start of the Sino-Japanese War.

Japanese engineers haul a field gun up a slope during fighting in south-western Shansi province in summer 1938. The Japanese Imperial army had to overcome the difficult terrain in large parts of China often using sheer muscle power to move heavier equipment. They utilized every type of draught animal during the campaigns in China and requisitioned any they came across, without offering compensation to the peasant owners. This particular ‘elite’ engineers unit had a reputation for moving equipment and weaponry at speed. According to reports, they always hauled guns and other heavy equipment at a ‘dog trot’ in action.

A Chinese Nationalist soldier shows a captured Japanese poison gas canister to the world’s press. Poison gas was used by the Japanese against the Chinese army throughout the Sino-Japanese War. The unreliability of gas as a weapon when dropped or sprayed from aircraft was probably the only reason that the Imperial air force did not utilize it on more occasions. Figures for the use of gas by the Japanese between 1937 and 1941 show that it was employed 9 times in 1937, 185 times in 1938, 465 times in 1939 and 259 times in 1940. In 1941 there was a marked reduction in the use of gas with only 48 occasions listed but it continued to be used to some degree until 1945.

Japanese troops storm into the outskirts of the city of Changsha, capital of Hunan province, which was fought over three times between September 1939 and January 1942. The original Japanese offensive against the city employed 100,000 men but failed to hold Changsha. A second attack in September 1941 was reinforced by a further 20,000 Japanese troops but again was pushed back after heavy fighting. A few months later a final offensive was launched but again after yet another battle for the city the Japanese withdrew their forces.

Nationalist troops remove bodies from one of the underground air raid shelters built for the population of Chungking in 1942. A direct hit on any of the manmade shelters or caves used as makeshift shelters resulted in horrendous casualties. Life in the wartime capital of Nationalist China was tough, especially for the poor who had to rely on what was provided by the government. The richer citizens of Chungking had their own private shelters built for them in the grounds of their houses.

A young female volunteer of the Nationalists Women’s Volunteer Corps is seen on sentry duty in Chungking in 1941. Girl volunteers were raised to help the regular army defend the wartime capital from the Japanese. Many recruits came from amongst the ranks of the thousands of students who had escaped the Japanese occupation. The volunteers wore cotton dresses and either a cotton side cap or a broad-brimmed sun hat, as seen here.

Massed ranks of officer trainees at the Central Military Academy at Chengtu in Szechwan province parade for their commander in 1942. Although the Allies were training Chinese troops in India and western China, the Nationalists continued to run their own military academies as well. Most Nationalist officers came from the higher classes of Chinese society and these men have been issued with smart uniforms not available to the vast majority of troops.

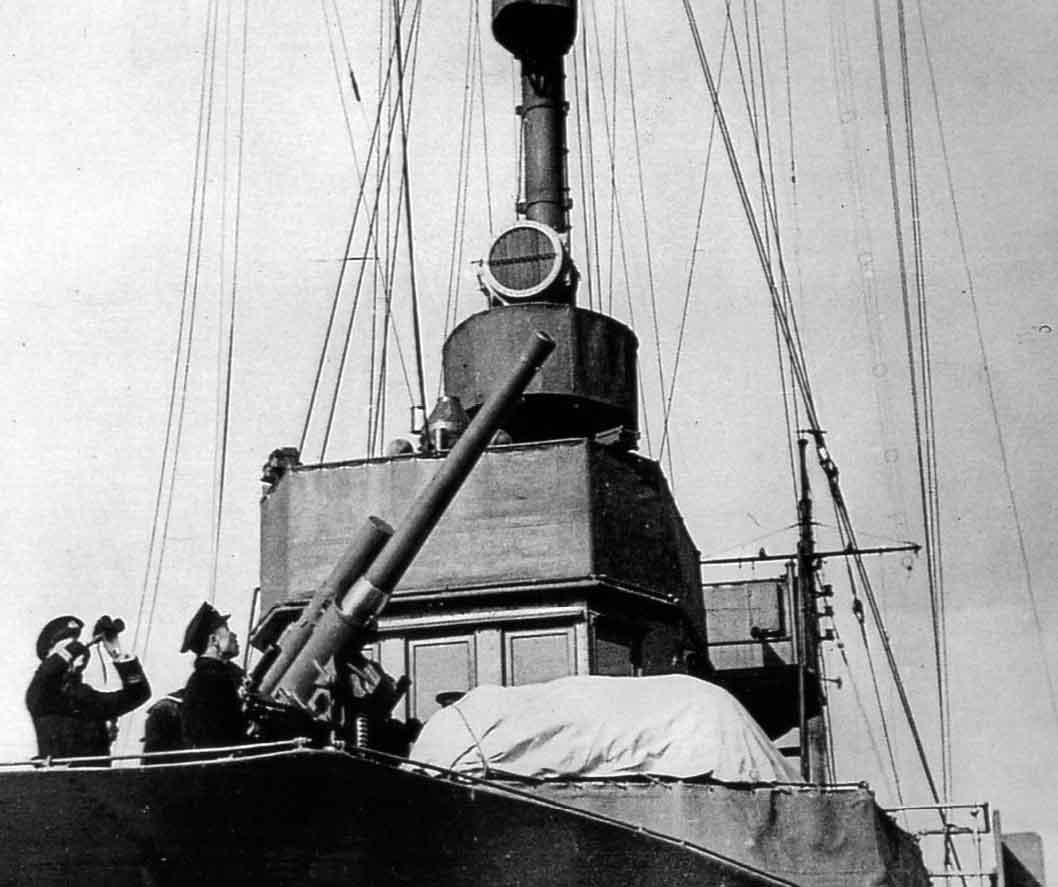

The crew of a Nationalist gunboat operate their deck gun against Japanese aircraft in 1942. After the initial fighting in 1937–8, the remnants of the Chinese navy saw little service, largely because of the total Japanese air superiority. Any Nationalist vessels that took to sea would face air attack and most remained hidden in small harbours or sheltered up rivers in southern China until 1945. Starting the war with fifty-nine vessels, most of which were gunboats and other patrol boats, the navy had to be rebuilt after 1945.

Chinese women labourers work to fill craters left after a bombing raid on an airbase of the famous Flying Tigers American Volunteer Group in March 1942. Before December 1941 this Nationalist Air Force volunteer unit was made up of US pilots who flew 100 US-supplied P-40 fighters against the Japanese. After Pearl Harbor and the entry of the USA into the war against Japan, the Flying Tigers were absorbed into the US Fourteenth Army Air Corps. Many of the ‘maverick’ US pilots were unhappy about this forced conversion of the Tigers into a regular US unit.

Nationalist troops celebrate a rare victory against the Japanese at Changsha and show off their ‘war booty’ in 1942. The soldiers pose with the body of one of their dead foes at their feet and are festooned in Japanese helmets, gas masks, flags and rifles. This third battle for the city began in December 1941 and ended in mid-January 1942 with the Japanese being defeated.

A couple of Nationalist soldiers are pictured wearing captured Japanese M32 steel helmets and mock firing the Imperial army Model 10 grenade launcher after the battle for Changsha in 1942. Fortunately, both soldiers have been told that the small mortar is not meant to be fired resting on the knee. The grenade launcher for some reason was known as the ‘knee mortar’ but if used in this way would result in a broken or fractured leg at the very least.