China’s Guerrilla War, 1937–45

One of the most brutal aspects of the Sino-Japanese War was the guerrilla war fought from the outbreak of the conflict in July 1937 until the final defeat of the Japanese in August 1945. The guerrillas fighting the Japanese were made up of Nationalists, Communists and other non-political patriotic groups. Other armed groups of bandits fighting the Japanese had no patriotic feelings at all and were only interested in any booty they could capture. In the first months of the war the Nationalist Kuomintang Party had organized irregular units to fight in support of the regular army. Any irregulars captured by the advancing Imperial army were instantly executed, although their regular comrades were subjected to the same treatment. When the Nationalist army suffered heavy defeats in 1937 and 1938 retreating soldiers often joined the guerrillas or formed bandit groups. The thousands of soldiers left behind by the retreating Nationalists had a few stark choices. They could join properly organized guerrilla groups, either Nationalist or Communist, or one of the local defence societies, such as the Big Sword Society. Many of these local defence organizations had been formed to defend their villages against warlord armies in the 1920s. Other disbanded soldiers joined bandit groups which attacked the Japanese as well as any Chinese regular forces that they encountered.

As the Japanese advanced and occupied more of northern and central China, Nationalist guerrillas began operating. These forces tended to be locally raised and commanded by Kuomintang Party officials. Many of these guerrilla groups could not be supplied by the central government, especially after the Nationalists moved their capital to remote Chungking in 1938. Any pro-Nationalist group which operated in the same locality as a Communist group usually found that they were under threat by their ‘allies’. The better organized Communist guerrillas would often absorb Nationalist groups by removing their leaders. If the Nationalist commanders were unwilling to join their men in the Communist fold, they were eliminated. Some pro-Nationalist leaders were happy to join their former enemies because they felt they had been abandoned by their government. The Nationalist central guerrillas operated throughout occupied China but one of their main strongholds was in Shantung province, where 170,000 guerrillas were based. Although the central guerrillas continued to fight until the end of the war the Communists had by 1945 pushed them into small enclaves close to Nationalist-controlled areas.

When it came to guerrilla warfare the Communists had a distinct advantage over their Nationalist rivals. They had effectively been fighting as guerrillas since the formation of the Red Army in 1927. Tactics and experience learned when fighting the Nationalists in the early 1930s was to stand them in good stead against the Japanese. Much of the fighting by the Communists was done by their few regular formations, some of which were at least officially under the command of the Nationalists up to 1941. The regular Communist forces, including the New Fourth and Eighth Route armies, fought a large number of engagements against the Japanese after 1937. For propaganda reasons the Communists’ claims about the level of their war effort were probably exaggerated. One of their commanders said that between 1940 and 1942 the two main regular Communist forces had engaged half of the Japanese divisions! Another claimed that the Eighth Route Army had launched six major offensives against the Japanese in the first six months of 1942 alone. Japanese reports did, however, confirm that the Communists were their main foe at least in northern China. Their reports often stated that the Communists would usually fight to the death and few ever tried to surrender.

In support of the regular units were a large number of irregular forces, known as the ‘Ming-Ping’ or militia. They assisted the regulars on operations but also fought their own low-level war against the Japanese. The strength of the Communist guerrilla force, or Ming-Ping, had expanded to over 2 million by 1944, but most of these were unarmed irregulars. Many of the guerrillas were armed only with crudely made spears and booby traps, mines and other improvised weapons like wooden cannon. They also had unsophisticated matchlock guns and cast-off modern guns handed on to them by the regular Communist troops. Usually, any up-to-date arms given to the Ming-Ping were those with little or no available ammunition. As more weaponry became available from captured arms taken from the Japanese, puppet troops or Nationalists, the Ming-Ping provided a ready-made reserve for the regulars.

From the start the Japanese Imperial army met the guerrilla threat with extreme brutality in an attempt to subdue any Chinese resistance. This approach often turned out to be counter-productive, however, as it gave both the fighters and the general civilian population little in the way of options. They could either actively support the guerrillas and face any retribution meted out by the Japanese or try and keep out of the war. When the civilian population were punished, whether or not they aided the guerrillas, many decided they had nothing to lose by helping them. In addition, some guerrillas punished any civilians who did not actively support them and local leaders would be executed as an example to others.

The Japanese employed a number of tactics designed both to protect the territory they controlled and to destroy guerrilla forces. They safeguarded the lines of communication between cities, towns and villages with barbed wire, fences and stockades. Their engineers dug ditches and built strongpoints along the roads and railways and manned forts with small garrisons. In total, the Japanese were reported to have built 7,000 miles of fences and other obstacles to protect the railways and erected over 7,000 fortified posts.

Armoured trains and converted armoured cars ran up and down the railways between strongpoints to try and combat the guerrilla demolition squads that constantly tore up the tracks. Mobile columns were sent out on anti-bandit operations from Japanese-held strongholds in an effort to bring elusive guerrilla groups to battle. To try and surround the mobile guerrillas, the Japanese built stockades around the Communist bases which were gradually moved inwards towards their HQ. The Japanese columns criss-crossed guerrilla-controlled areas to push their units into a smaller and smaller perimeter. As the Japanese advanced they employed their policy of killing anyone they came across, as well as livestock. In this way they hoped not only to destroy active guerrillas but to cut them off from any hope of support from the local population.

One policy that the Japanese hoped would assist them in controlling China was the raising of ‘puppet’ units to fight for them. Since 1937 they had formed governments in northern and central China which were staffed by local collaborators. These puppet states were given titles, such as the Provisional Government at Peking in 1937 and the Reformed Government at Nanking in 1938. In 1940 a central puppet government was formed which officially united all previous governments under the former Nationalist leader Wang Ching-wei. The so-called Reorganized Government had its capital at Nanking and claimed to be the ‘true’ Nationalist government of China. It was ‘allowed’ or forced to recruit an army, navy and air force to fight alongside the Japanese against the guerrillas. In total the so-called Nanking Army reached a strength of 300,000 regulars with a small number of tanks and artillery pieces. Other local ‘puppet’ troops added several hundred-thousand to the official strength of pro-Japanese units, although these were totally unreliable. Nanking Army units went out on anti-guerrilla operations with Japanese units and performed reasonably well under their supervision. When fighting independently, however, they usually avoided combat with the guerrillas and often provided them with weapons and ammunition. Most puppet soldiers had no loyalty to Wang Ching-wei or the Japanese and many were absorbed into Nationalist and Communist units in August 1945.

A pro-Nationalist Chinese guerrilla fighter poses at his base along the southern coast of China. Even in the south of China, closest to Nationalist-held territory, it was difficult for fighters like this to get arms and ammunition. This man is well armed and has plenty of ammunition pouches on his belt, although they may or may not be full of clips for his Mauser rifle.

A Japanese signal unit in northern China uses dogs from the Canine Corps to transport carrier pigeons in wicker baskets. Imperial army signal units used the latest radio and telegram equipment alongside carrier pigeons, trained messenger dogs and couriers. As with weaponry, sophisticated communications equipment was withdrawn from China and sent to other theatres after 1941.

A mixed patrol of Japanese and ‘puppet’ Chinese troops take a break during an anti-guerrilla operation in 1942. The Chinese troops of the Nanking government, under the leadership of Wang Ching-wei, co-operated with the Japanese between 1940 and 1945. Wang, a former colleague of Chiang Kai-shek, became a puppet of the Japanese in 1939 and formed the so-called Reorganized Government in Nanking.

An elite unit of the puppet Nanking government’s army marches out of its barracks to support its Japanese allies in 1941. At the head of the column is the flag of the puppet regime, which is almost identical to the Nationalist Chinese army flag. The only difference is the yellow streamer at the top of the flag, added at the insistence of the Japanese. The black characters on the streamer state the anti-Communist intentions of the Nanking government.

Anti-Communist, spear-wielding militia on parade in Shansi province as they cooperate with the occupying Japanese. Not all Chinese peasants flocked to join the Communists and members of several societies like the Red Spears actively fought against them. Only the commander on the right appears to be armed with a rifle and these men would be of little use to the Japanese.

Since the early 1920s armoured trains had been used in China by warlord armies, and many were captured by the victorious Nationalists in 1928. They joined those already in service with the Nationalists, who used them against the Japanese from 1931. Most of these were in turn captured by the Japanese Imperial army who used them to patrol occupied Chinese territory. This train appears to have been one of those in Chinese service and has Japanese-pattern camouflage added. Some were adapted by the Imperial army and fitted with Japanese guns and machine guns.

Japan’s control of the railways of northern and eastern China was vital in keeping garrisons supplied. As the railways were under constant attack by guerrillas, armoured trains and vehicles ran patrols along them. This Sumida Model 93 armoured car has been converted to run along the tracks with specially trained troops aboard it. It was reported to take 10 minutes to convert this vehicle from a road-running to a rail-riding vehicle.

Japanese soldiers crowd aboard a rail workmen’s truck as they move up the railway on patrol. Their role is to try and stop any destruction of the track by guerrillas or their civilian supporters. The rail network in occupied China was often protected by fences, barbed wire, strongpoints and constant patrolling by the Japanese army and Chinese puppet troops. The local population was often given responsibility for the section of the railway that ran past their village or town. If the railway was damaged, then village headmen or other leaders often paid with their lives as an example to the peasants.

Nationalist guerrillas aim for Japanese positions from their hilltop location in Chekiang province with a mix of rifle types. With no heavier weaponry available, the best that they could hope for is to fire off a few precious rounds and then withdraw. Although the men have no uniforms, they have written patriotic phrases on their bamboo sun hats. If a guerrilla or irregular was captured, the bruise left by the rifle butt on their shoulder would mean a death sentence.

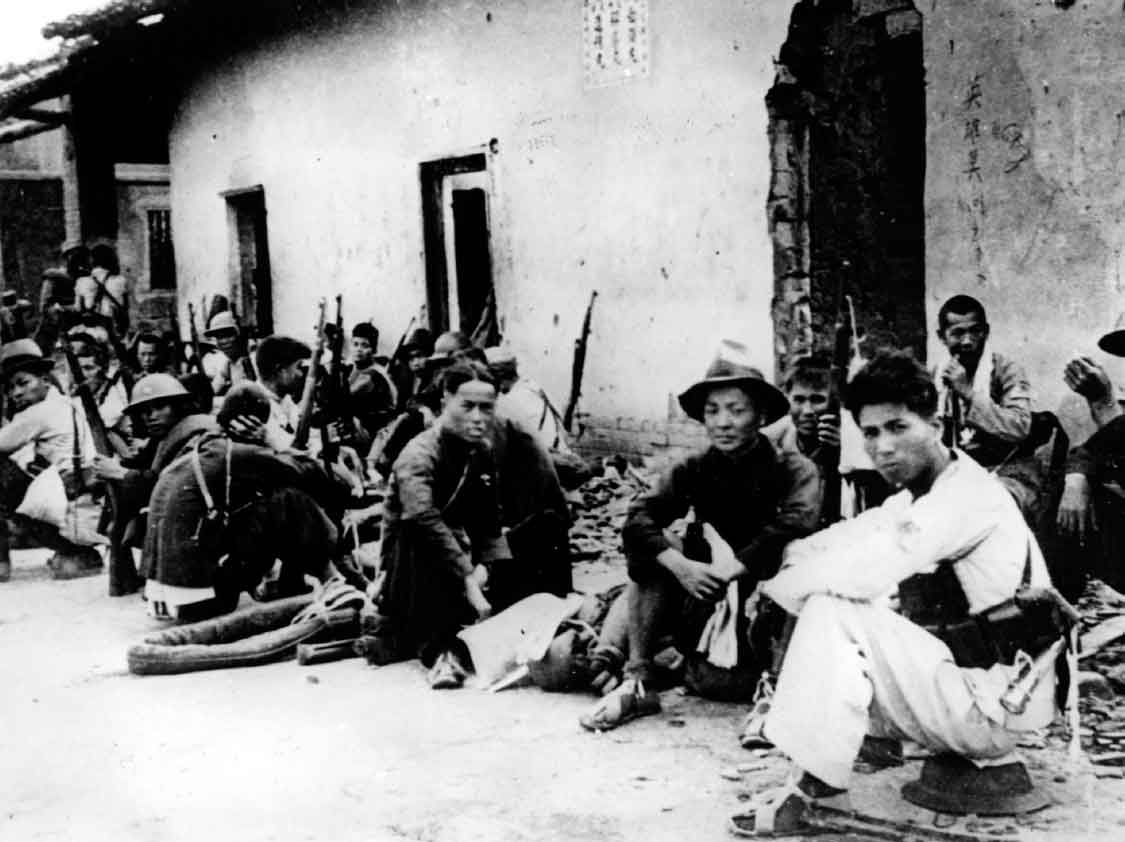

Nationalist soldiers turned guerrillas gather outside their temporary headquarters during fighting with the Japanese army in 1941. On many occasions during the Sino-Japanese War large numbers of Nationalist troops were cut off by the advancing Imperial army. They had little choice but to continue to fight as guerrillas and many were absorbed into Communist groups before 1945.

A couple of young Nationalist guerrillas look nervously towards Japanese positions during an engagement in summer 1938. With just their rifles and a few rounds of ammunition they could only offer limited resistance to the advancing Imperial army. Along with thousands of their comrades, youths like these would be sacrificed in battle with the Japanese.

An elderly Nationalist guerrilla commander heads a unit of pro-Chiang Kai-shek irregulars in southern China. Most Nationalist guerrilla groups were led by local Kuomintang officials whose strength of personality often held their men together. They usually came into conflict with the Communists as much as with the Japanese and were often destroyed by their fellow Chinese, especially in northern China.

A well-uniformed and well-armed Communist unit put their Japanese Type 11 light machine gun into action in 1938. They have set up their machine-gun position on the heights overlooking a section of the Great Wall of China. By including the wall as part of the backdrop of their photograph the Communists give the impression that they control northern Chinese territory.

The Communist crew of this ex-German PAK 36 37mm anti-tank gun pose proudly with their rare piece of artillery. It is missing the shield but would be a welcome addition to the poorly equipped Communist forces. As with all Chinese heavy weaponry used in the Sino-Japanese War, replacing ammunition when supplies ran out was a major problem. The shells held by the crew could well be the only available for the gun so would be strictly rationed. They could not expect any ammunition from the Nationalist army unless they captured some from them.

Civilians are given some rudimentary training in defending their town against Japanese attack by Nationalist army officers in 1938. The young men and women of this group are armed with a few hoes and the odd rifle supplied by the army. If they tried to fight the ruthless Japanese Imperial army by themselves, their fate would be fairly grim. They would be better employed, like Communist irregulars, in attacking the Japanese supply lines.

A column of Communist regulars marches through a village and are armed to the teeth with Thompson submachine guns. The image is really an example of Communist propaganda as there was little ammunition available for these guns. They are copies produced in the arsenal of the Nationalist Shansi warlord, Yen His-shan. Because of the shortage of bullets for these weapons, later they had to be handed over to their irregular comrades.

With fists clenched, the eight-man crew of an artillery piece of the Communist New Fourth Army pose. The gun is a captured Japanese Type 41 75mm mountain gun which would have been a rare weapon in the Communist arsenal. It was a particularly useful gun for a guerrilla army as it could be easily broken down into six sections and transported on mules or ponies.

A trio of Communist machine-gunners pose for this propaganda photograph with their captured Japanese Type 3 heavy machine guns. Here two of the guerrillas give the cameraman the ‘thumbs up’, while the other has lost his arm during the war. The Communists depended on their enemies including puppet troops to supply most of their weaponry. Puppet troops even loaned their machine guns to the Communists as long as they were returned whenever the Japanese inspected their units!

Japanese cavalry charge across a Chinese river at full gallop with their Model 44 cavalry carbines slung over their backs in 1943. The Imperial army’s cavalry units came into their own in the fighting in China and played an important role in most anti-guerrilla operations. All these troopers are wearing winter coats and have extra ammunition in the canvas ammunition pouches worn around their waists.

Japanese youth volunteers who have been sent to China to bolster the weakened Japanese garrisons after 1941 are spending a day working in the field. As more and more front-line troops were moved to the Pacific and Burmese theatres, ‘patriotic’ volunteers like these were sent to replace them. As they often came under attack while away from the relative safety of their garrison, these young men were usually armed.

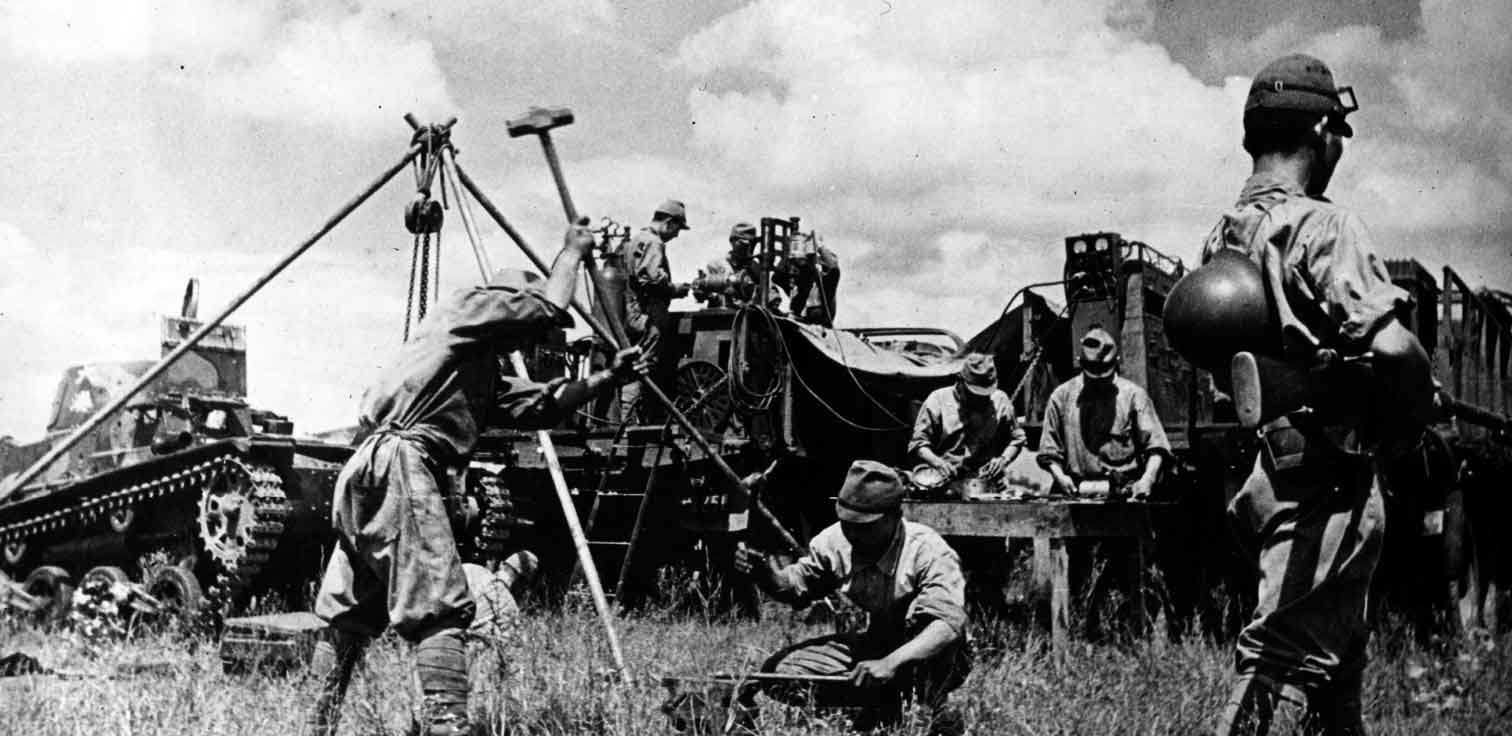

A Japanese mobile workshop in northern China repairs Type 94 tankettes in the field, while a sentry guards the workmen. As less equipment and weaponry was sent to China after 1941, it was essential to ensure the existing tanks, trucks and other vehicles were well maintained. The Japanese Imperial army’s second line units were increasingly in danger of guerrilla attack in China during the early 1940s and the guard must be on the alert.

A column of marching Communist guerrillas move through a village to show their strength to the people. The fact that no firearms are visible amongst this group points to the severe shortage of rifles in the Communist ranks. Nearly all the firearms used by the Communists were captured from the Japanese or the Nationalists. Under the terms of the United Front signed in 1937 the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek was supposed to supply them with weapons. Not surprisingly, few rifles or machine guns were supplied, except in the form of captures from the Nationalists.

Hiding behind a tree, Communist guerrillas prepare to pull the chord to ignite a ‘string-pull mine’ aimed at a passing Japanese patrol in 1945. Communist irregulars supported their regular comrades in the New 4th and 8th Group Armies from 1937–45. As the regular Communist forces expanded these men were easily absorbed into their ranks as a ready trained reserve. Rifles were always in short supply with the guerrillas and homemade booby traps had to be used in their place.

Well-armed Chinese Nationalist guerrillas on parade at their base in late September 1942. These men belong to a so-called ‘Revenge Detachment’, raised from civilians whose families had suffered under Japanese occupation. The older man near the centre of the group is the leader and is armed with a old C-96 automatic pistol. According to the original caption to the photograph, the whole of his family was killed by the Japanese and this led him to form this resistance group.

This Czechoslovakian Communist postcard was published after the Second World War in celebration of the Chinese Communist army and guerrillas during the conflict. It shows the meeting between regulars of the Communist New Fourth Army and their guerrilla comrades. The Communists relied on the large irregular force to replace casualties in the regular New 4th and 8th Group armies. Although romanticized in this image, the unity of the Communist forces was to lead to their victory in the post-war civil war with the Nationalists in 1949.