In which two humans with little in common come together (for tea) and a common cause.

“The idea was to show how two people can live in identical apartments in the same building and yet live so differently from each other.”

UK producer Phil Collinson describes a set for the Good Omens shoot as if it has to be seen to be truly appreciated. On paper, two dwellings divided by a corridor shouldn’t spark such enthusiasm. In reality, and in keeping with the production, the design, detail and meaning invested in the combined spaces lifts it from the mundane to the sublime.

“It was one of the best set builds I’ve ever stood on,” continues Phil. “The apartments are the mirror image of each other, but contrasting in every other way. One is tidy and feminine and pink while the other is a mess. It looks like it belongs to an old guy with his mind on other things. We spend a lot of time there,” he says, “and so we wanted to make it as visual as we could. So, you head up the stairs, turn right and it’s shabby, dirty and cramped, or you turn left and it’s a nice place to be.”

The first apartment Phil describes is home to a character that is memorable in the novel and unforgettable in the adaptation. In her own right, Madame Tracy is a woman of two halves. In one guise she entertains lonely gentlemen, which pretty much amounts to making cups of tea for them and listening with the occasional hug thrown in. In the other, Madame Tracy swaps her stockings and garters for the psychic’s veil and endeavors to fulfill the needs of a very different kind of clientele. As a sex worker and clairvoyant, played with great relish in the TV series by Miranda Richardson, she’s a kind soul who seeks to bring people comfort in an odd sort of way.

This generosity extends to her shambolic neighbor and occupant of the flat opposite. Shadwell might reject everything Madame Tracy stands for, in his role as self-appointed Witchfinder Sergeant, but then this is Good Omens, and in Good Omens opposites attract. Or at least find a space in the middle where they can connect.

For both Madame Tracy and Witchfinder Sergeant Shadwell, this grubby phone booth forms the center of their operations.

Christopher Raphael © BBC

With a corridor dividing the two flats, symbolically keeping two contrasting characters apart, Madame Tracy and Shadwell meet in the middle when Newt arrives in their lives.

Christopher Raphael © BBC

“It was liberating for me,” says the director of photography Gavin Finney. “Each space was perhaps slightly bigger than it would be in real life, and so cleverly designed so we can see how they’re used in completely different ways.” With the build conceived purely for filming, Gavin describes how he was able to bridge the two apartments-without-ceilings in a unique way. “Douglas wanted us to fly over the top,” he says. “So we start in Shadwell’s flat and then follow the action over the hall into Madame Tracy’s flat. The lighting for each one is very different, but these are wonderful challenges.”

For Good Omens’ production designer Michael Ralph, the inspiration for this set build stemmed from a photography exhibition that focused purely on doors in residential tenement blocks.

“It mesmerized me,” he says. “Each door was open, with the camera pointed through the doorway to show how that person lived inside. So every photograph offered a glimpse through the same frame into a unique world. I wanted Madame Tracy’s flat and Shadwell’s flat to be identical in the same way, but different worlds if you walked from one to the other.”

Christopher Raphael © BBC

Christopher Raphael © BBC

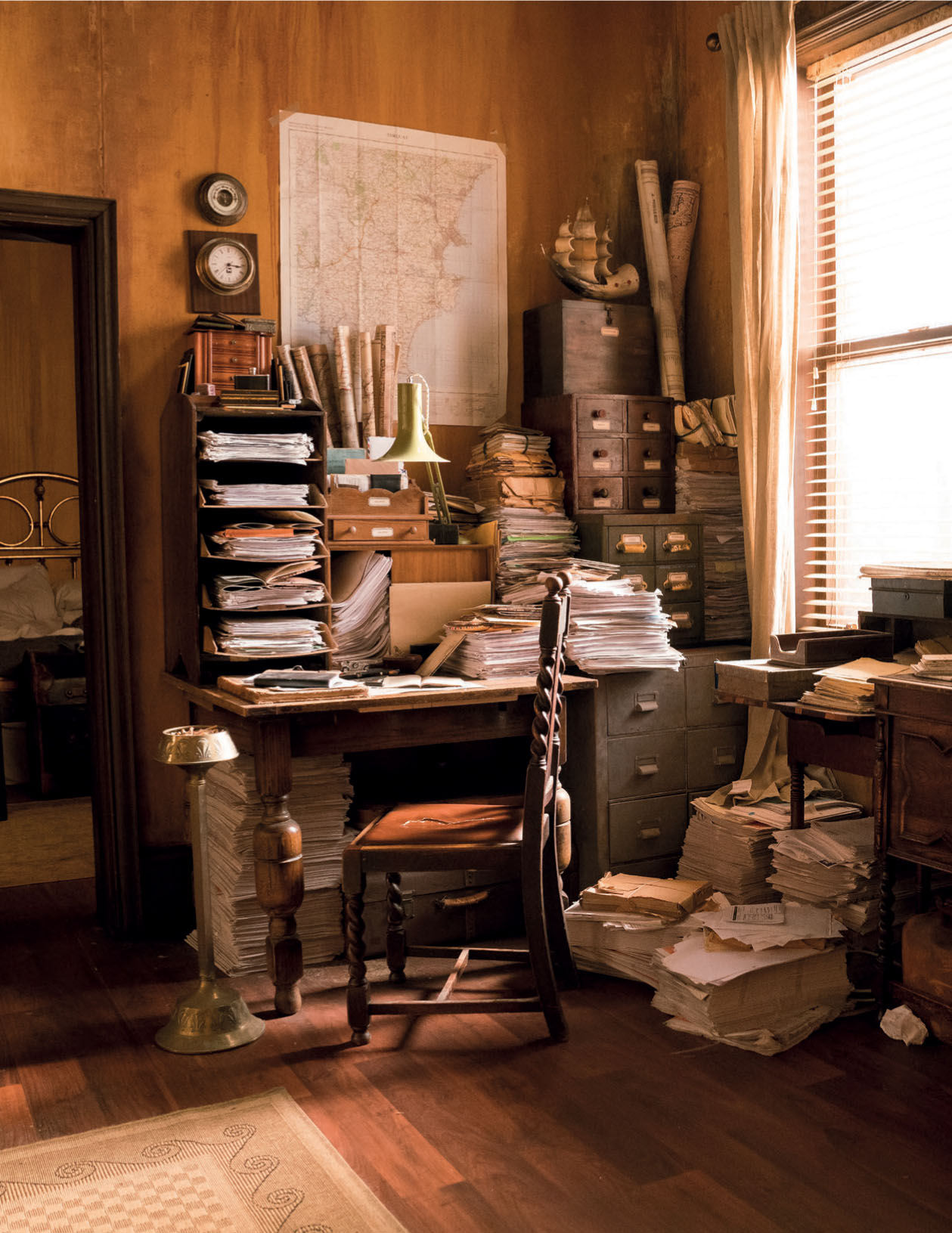

Shadwell’s shambolic flat reflects his character, and yet production designer Michael Ralph, foregrounds a sense of beauty in such a chaotic environment.

Christopher Raphael © BBC

Christopher Raphael © BBC

Christopher Raphael © BBC

Across the corridor from Shadwell’s, Madame Tracy’s flat is the mirror image in terms of design and contrasting in every other way.

Christopher Raphael © BBC

While the two apartments are recognizably the same on a structural level, Michael Ralph lent both his trademark twist with features that remove them one step from reality.

“I deliberately designed arches that the viewer has never seen before,” he says, “and also fireplaces that look Georgian but they’re not from that era. I invented an architecture that looks familiar but doesn’t really exist!” he jokes.

Michael also manipulated each space for maximum impact on the viewer. “I raised the corridor up five steps from each flat. So when we visit each apartment the audience has a chance to submerge into their world rather than walk in on a level.”

The task of decorating each flat to reflect the personality of the occupant also fell to Michael. In furnishing the Witchfinder Sergeant’s abode, the production designer oversaw the placement of every last unwashed plate and cigarette burn as if it were an art installation.

“Shadwell lives in this shambolic nicotine-colored, single-man dwelling. There’s one chair and one lamp, and the couch is covered in so much stuff that nobody ever visits. It was phenomenally beautiful,” he says.

Turning to Madame Tracy’s apartment, Michael sought to bring a range of influences together to create a whole in terms of fixtures, fittings and furnishings that was greater than the sum of its parts.

“I wanted it to be multi-religious and multi-cultural so she looks like some kind of European mystic living within a multi-colored tapestry,” he explains. “On camera it was quite incredible. Everything came together to create a tangible world.” When Madame Tracy switched from her role as mystic to sex worker, Michael reflected the transformation accordingly. “We threw black cloths over lamps and lit candles so the light source changed,” he says.

Having created two worlds divided by a corridor, Michael Ralph joined the rest of the crew in watching these two legendary actors at work. Within their respective homes, both Miranda Richardson, who plays Madame Tracy, and Michael McKean as Shadwell come across as naturals in their roles, and it’s no surprise to learn that both were first choices for Neil. Much is down to their formidable acting heritage and comic flair, but this is reinforced by the creative work of the costume, hair and make-up departments.

“Neil and Terry’s writing is very succinct,” says costume designer Claire Anderson, who has previously worked on productions including American Gods, Black Mirror, Royal Night Out and State of Play. “It means costume comes off the page very clearly for many of the characters. So in Good Omens we built from what we have in the story to what audience perception would be to what would look comfortable and timeless.”

In terms of dressing characters as distinct as Shadwell and Madame Tracy, Claire outlines a process that turns the script into a creative springboard. “I meet with the producer and the director,” she says. “I read the book, and consider factors like the fanbase because everyone has an expectation, and I also work with the actors. Then I put visual moods together for each character. Sometimes ideas get abandoned and other times it’s the first idea that you roll with.”

With ideas evolved into sketches, Claire emphasizes the importance of the color palette in defining her characters. “Aziraphale needed to be light and cream, iridescent and ethereal,” she says, “and Crowley had to be black.”

As for Shadwell, “He’s a grubby and disheveled character and his colors reflect that.” Neil Gaiman had his own take, suggesting Shadwell’s look should be informed by a much-loved eccentric called Stanley Green. With his placard urging “less lust by less protein,” Green was a familiar sight on London’s Oxford Street from the late sixties until his death in the early nineties. In Good Omens, when Newt first comes across Shadwell clutching a sign with an anti-witchcraft message that could have come from a discarded draft of the Bible, Shadwell’s whole stance and visual appearance might be considered as a fond homage to the “Protein Man.” Shadwell’s jacket, however, is what truly defines his look.

“As he came from the witchfinder route I wanted elements of uniform about him,” explains Claire, who subsequently trawled through history in assembling a suitable look. “I created a moodboard full of witchfinders and used that to influence the shape and style of his clothing. We went for a Barbour jacket with a cape and a fishing bag, which has a slightly timeless oddness about it. We then adorned it all as Neil and Terry had written, with badges made from everything from assorted wine labels to tin labels on chains that hang off whisky bottles.” Claire describes the range of details in her costume work with great enthusiasm. “It helps the audience determine what family each character belongs to,” she says. “It’s semiotics.”

Christopher Raphael © BBC

Christopher Raphael © BBC

The Witchfinder at work. Shadwell’s tools of the trade, from the maps that take him to Tadfield, along with the lapel badges of office to an original witch bell.

Christopher Raphael © BBC

As the series costume designer it was important that Claire Anderson, seen here looking on as Miranda and Michael prepare to shoot a scene over a pot of tea, was on hand throughout filming.

Christopher Raphael © BBC

In dressing Madame Tracy, Claire Anderson took the view that she was dealing with two characters.

“You can tell what people do from what they’re wearing. She’s a part-time mystic and a sex worker. So it was easy! I gave her a flowing gown and colors that make her look kooky,” says Claire, describing Madame Tracy’s psychic guise before explaining how she dressed her in a flamboyant kimono for her scenes as a lady of the night. “Then, for the scooter ride to Tadfield I harked back to the traditional helmet and a cape, which is in fact a Welsh tapestry blanket. I have a magpie eye,” she adds, “and this is a production where I can be wide-ranging and free. Nobody belongs in real time. Even Madame Tracy has something of the 1960s about her, which is something Neil wanted to see. Most of the stuff is made specially,” Claire adds. “You can’t just nip to the shops and buy it, which is why fantasy costume is so enjoyable. It’s better than Jane Austen as it’s new and fresh and exciting to explore.”

Nosh Oldham has an equally big influence on each character’s appearance. As the Good Omens hair and makeup designer, her CV boasts productions including Downton Abbey, Luther and Strike, based on the detective novels by Robert Galbraith aka J. K. Rowling.

“I do a lot of period stuff, but I started in blood and guts,” says Nosh breezily, referring to her early work on films such as Antonia Bird’s 1999 black comedy horror, Ravenous.

Working closely with costume designer Claire Anderson, “so the head fits the body,” as she sees it, Nosh Oldham seized upon the opportunity provided by Douglas Mackinnon, who invited her to be bold.

“It was a huge canvas,” she says, “and I aimed to be striking, quirky and unusual. Working with a period drama can be restricting to a point, but Good Omens goes from Adam and Eve onwards. It meant I could pretty much take my inspiration from anywhere—every place and time.”

Beginning with mood boards, Nosh works by collaborating with the main cast and evolving a singular look for each one. In particular, she says, working with Miranda Richardson was a joyful experience.

“She’s spectacular in every possible way,” she says. “Very creative and visual as well. So for the psychic Madame Tracy we looked at portraits of women by the German painter, Otto Dix. Together, we thought that she would work rather well with wrapped-up hair, red and finger-waved, and extravagant makeup. Then, when Miranda was playing the naughty girl, who we called ‘Sexy Time,’ we went for the seaside picture-postcard look. It was quite doll-like with the sixties vibe, and we stuck closely to that.” Nosh stresses how each look had to be distinctive. “Madame Tracy plays these roles as part of her job,” she says. “She’s a character playing characters, and Miranda had a lot of input. She was great fun, and we agreed on a look that gelled with what we had in mind.”

For each character, Nosh creates a hair and makeup mood board from a wide and diverse range of media to provide a visual starting point for the look. Aziraphale’s board is predominately white and silver in theme, with images of a silver-haired David Lynch and diaphanous platinum blondes, while black imagery dominates Crowley’s board along with close-ups of reptilian eyes.

“It’s a mangle of stuff, but depends on who you’re given,” Nosh explains. “Shadwell was a divine creature, who I made look like the nicotine man. In the script he smokes a lot and takes too much sugar, and so I felt he should look unwell. I also ‘nicotined’ his fingers and face so that you could see he was a real smoker. Michael was great with it all,” she adds. “He grew his hair, which we left unwashed, and went unshaved. The more an actor can give us like that, the easier it is.”

With the set dressed and the characters complete, it was Miranda Richardson who provided what many crew members consider to be the most entertaining shoot in the vast schedule.

“It was the scene of one of the most memorable moments,” Nosh says, referring to the séance Madame Tracy hosts in Episode Five for clients including Mrs. Ormerod, Mr. Scroggie and Julia Petley. Once the colorful medium has reminded them that her spirit guide needs twenty-five pounds, it should be a routine commune with the afterlife, and in particular Mrs. Ormerod’s husband, as she wants to tell him about some broken guttering. However, it takes an unexpected turn when the discorporated Aziraphale makes a spirited appearance as an angel in need of a body to inhabit so that he can reach Tadfield and head off Armageddon. Having already materialized live on air in the body of an American television evangelist, somewhat uselessly in Florida, the angel comes to occupy the medium and sex worker with riotous results.

“It was a lovely period of work,” says first assistant director Cesco Reidy. “Miranda was a delight, and Michael is absolutely brilliant. With Miranda in charge of the crystal ball, the séance made us laugh on the floor more than anything else. Just to be on the set that day will stay with me for a long time. It was high comedy. Just very, very funny.”

“In true Good Omens style, that scene was totally off the wall,” agrees script supervisor Jemima Thomas. “Miranda went for it with the most amazing performance. Douglas asked for a ten and she gave it eleven.”

Sophie Mutevelian © BBC

Sophie Mutevelian © BBC

Out of hours. Madame Tracy’s flat was designed to change in terms of lighting and soft furnishing to reflect the nature of her role either as a sex worker or psychic medium. A bed piled high with pink and fluffy toys signals she’s off duty while her reference books and crystal ball create an air of clairvoyant chintz.

Sophie Mutevelian © BBC