WHAT WAS HE thinking?

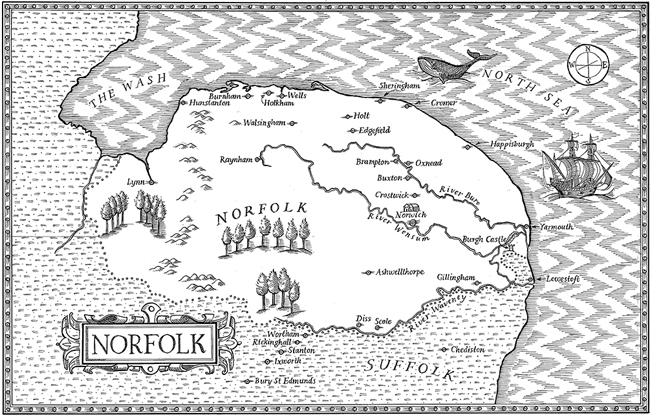

What was he thinking that morning in 1662 as he set out from the spring assizes at Bury St Edmunds towards his home in the city of Norwich? It was a full day’s ride in fair conditions, and all the more arduous in this season when the road was liable to be churned to mud or sheathed in ice. He would have many hours to reflect, if he chose, on what he had said and its consequences.

A few days before, his words had done nothing to prevent two women from being sent to their deaths.

He had been present at a trial of two witches. Six girls and an infant boy, all of Lowestoft in Suffolk, were said to have been bewitched. The girls were a mute presence in the court, perhaps intimidated by the formality of the proceedings, or too scarred by their experience to speak up. Parents gave zealous testimony on their behalf. Each of the children had suffered fits and bouts of lameness and was said to have vomited up pins and nails. They had accused two widows, Amy Denny and Rose Cullender, of afflicting them. Amy Denny was the main culprit. She was a quarrelsome old woman, well known to the townspeople of Lowestoft, occasionally used by some of the parents for childcare, but had been put in the stocks the previous year by one of them for some unrecorded misdemeanour. Rose Cullender seems to have had less direct association with the children, and may simply have been fingered as another awkward old crone who would add weight to claims of witchcraft. The accused women were present in the courtroom, with Amy in particular shouting out in violent rebuttal of the denunciations made against her.

His name was Thomas Browne, and he was a physician by profession, trained at the best European schools of anatomy and medicine. He was also a philosopher and writer, a coiner of words, a Christian moralist, a naturalist, an antiquarian, an experimenter and a myth-buster. Called before the Bury assize as ‘a Person of great knowledge’, he was asked by the three serjeants-at-law for his opinion of the evidence they had heard.

What he said next was brief and was not in itself pivotal to the verdict handed down, but it can only have helped send the women on their way to the gallows. Browne recounted news of a ‘Great Discovery of Witches’ lately in Denmark, who had stuck pins into ‘Afflicted Persons’ in just the same way that Denny and Cullender were accused of doing. He offered his physician’s opinion that the fits and other symptoms exhibited by the children were natural. Almost gratuitously, it seems, he then added the thought that this very naturalness was evidence of the ‘subtilty’ of the devil, who was controlling the witches’ actions.

The serjeants had been divided before Browne spoke, uncertain they had heard enough to convict the women. Now his casual anecdote, which might have been taken as hearsay but for his learned reputation, made them think again. As for Browne, duty done, he probably did not remain in Bury for long after the trial to see the women hanged. He had patients waiting to see him in Norwich.

I decide to pursue Thomas Browne on his journey from Bury to Norwich.

The Shire Hall where the 1662 assizes were held no longer stands. The site where Honey Hill runs down to the watermeadows of the rivers Lark and Linnet has been redeveloped with modern council offices. But other parts of the town have changed little, and it is obvious what route Browne would have taken. In order to approximate the scale and texture of Browne’s journey, to match its pace and to be able to see what Browne would have seen, I go by bicycle. I want time to think about what was going through Browne’s head.

I am grateful for a mild and dry day as I set off, 350 years to the month after Browne. Weather records for 1662 show the spring to have been kind that year too, and perhaps in the end Browne made good speed. I pedal up Honey Hill, and turn right at the vast parish church of St Mary’s to head down the broad sweep of Angel Hill past the extensive complex of St Edmund’s Abbey, much of it as Browne would have seen it, in ruins since the dissolution of the monasteries, its stones ransacked for godless new buildings. I skirt the great marketplace where Denny and Cullender were briefly imprisoned before they were hanged, and turn right again onto Eastgate, crossing over the river past the old Edward VI grammar school. Then it’s up the long, slow incline onto the exposed road east.

To the shepherd or woodsman who chanced to see him pass by, Browne would not have cut an imposing figure. He was in his fifties, of slight build and habitually plainly dressed for a man of his standing. The bystander would have gleaned nothing from this unpromising exterior about the man’s remarkable heart and mind. Browne was loved by his patients, who admired his readiness to treat rich and poor, Catholic and Protestant alike. He was more widely renowned, too, as the author of philosophical essays. The earliest of these contentiously sought to reconcile his rationalism as a physician with his Christian faith. Others, more in the spirit of the age, discuss antiquities and the meaning of death or the significance of pattern and number in nature. His greatest and most popular work, though, was a vast catalogue of ‘vulgar errors’, seven volumes of foolish common beliefs of the seventeenth century, each in turn set out and then learnedly, scientifically, gently and humorously debunked.

He could write this humane and sceptical work, and yet he believed in witches. He freely gave his opinion on the existence of witches before and after the incident at Bury. But of the trial itself, he seems to have had no further thought. Was it for him simply a matter of course? Was it an episode to forget?

I settle to a steady pace as I cycle through the ancient villages of Ixworth and Stanton and the Rickinghalls Inferior and Superior, and then run across the heaths and commons of Wortham and Palgrave to skirt the marshes south of Diss. The blackthorn is coming out. Perhaps Browne was able to immerse himself in the details of awakening life as he rode on. Perhaps his horse flushed up skylarks from the Breckland scrub and he caught the scent of herbs familiar from his own physic garden. On my journey, though, I see mainly flattened drinks bottles, hubcaps in the hedgerows, and dead pigeons batted aside by the speeding traffic.

He may have smiled when he reached the Dolphin Inn at Wortham. At the time he was in the middle of gathering observations that would go towards the compilation of Notes and Letters on the Natural History of Norfolk, a catalogue of the birds and fishes found in the county. He offers a clear description of the common dolphin, so as to distinguish it from the porpoise. The animal has a ‘very good taste to most palates’, he adds.

The inn has a forlorn air that its pink paint is unable to lift. A young couple nurse their ciders, at a loss for conversation at its single picnic table on the green. Its sign is simple gold lettering on black with a token squiggle of ornamentation. Perhaps there was once a painting of a dolphin, not as accurate as that given by the French naturalist Rondelet, which Browne took as his guide for identification, more likely the stylized version of heraldry, a leaping arch of muscle. Browne devotes an entire volume of Pseudodoxia Epidemica to ‘things questionable as they are commonly described in Pictures’, and one of his subjects is the dolphin. He worries that people will think they actually occur in nature as they are habitually depicted, in this scoliotic way rather than lithe and flexible of spine. Such an argument might seem pedantic, like the person today who points out that a cartoon figure is unrealistic, but it matters in an age when uncritical belief in images frequently triumphs over observation and reason.

Occasionally, amid the prairie-like fields, there are orchards of budding apple trees, and I look over to see if they are arranged in the manner celebrated by Browne in his essay on horticulture, The Garden of Cyrus. Browne was captivated by the ancient custom of planting orchards in overlapping quincunxes, modules of five trees set out in an X like the five dots on a die. The essay revels in the subtitle The Quincunciall, Lozenge, or Net-work Plantations of the Ancients, Artificially, Naturally, Mystically Considered. It is a work of skilled scientific observation rooted in the East Anglian landscape, but also a disquisition of quite startling breadth, taking into its ambit the origins of gardens, the shapes of various crosses, ornament in classical architecture and the art of the lapidary. Holding it all loosely together is the number five, the generator of so many patterns and repetitions in nature.

I recall the moment when Thomas Browne invaded my life. It happened when I was writing a book about the discovery in 1985 of a new form of carbon called buckminsterfullerene. This form of the element has atoms bonded to one another in such a way as to form a curved pattern of hexagons and pentagons like the stitching on the surface of a soccer ball. The pentagons that punctuate the surface of the buckminsterfullerene molecule would make a fine addition to Browne’s miscellany of the five-fold.

As I travel on, I cannot help seeing Browne’s mysterious signs of natural order everywhere I look. They are visible in fallen pine cones and the wind-dried heads of teasels, and in the ‘catkins, or pendulous excrescencies of severall Trees, of Wallnuts, Alders and Hazels, which hanging all the Winter, and maintaining their Net-worke close, by the expansion thereof are the early foretellers of the Spring’. I think of the starfish and viruses that also exhibit five-fold symmetry. It is clear that this number really does have a special place in nature. It is even strangely evident in the man-made world, I realize. Most of the hubcaps in the hedges are perforated with five holes and have the same pentagonal symmetry as Browne’s flowers and seeds.

The words of the trial echo through my head. I see that in his own mind, if not in the view of the judge and complainants determined to return a guilty verdict, Browne’s contribution was carefully equivocal. He had called the children’s affliction natural, and had added that their malady was merely heightened by the agency of the devil. He had never said they were caused directly by witches, nor that those witches were the women in the court. Such equivocation is characteristic of Browne and marks him apart from most men of his time. He could always see both sides of the argument. Sometimes, this was a virtue – it was not easy to keep a level head and maintain an attitude of tolerance during the English Civil War. At other times, he is equivocal to a fault, marshalling the arguments for and against some dubious phenomenon in nature or metaphysical nicety with the greatest eloquence, yet never coming down on one side himself.

Did he feel that his medical view that the children’s suffering could be regarded as entirely natural had been given due weight? Or did he regret that it had been swept aside by more melodramatic testimony, by the impassioned pleas of the parents, by the pitiful appearance of the silent children, and by his own careless afterthought about the Danish case? Did he consider what he could have said that might have led to a more humane outcome? Did it ever occur to him to suggest that a belief in witches, while still perfectly respectable and perfectly tenable in 1662, was actually rather old fashioned, and in fact well on the way to becoming superstition, another ‘vulgar error’?

Of course, we cannot know. Indeed, we cannot even be sure exactly what Browne said in court. The only record of the trial was made twenty years later. We cannot be sure, therefore, that its account of Browne’s evidence is accurate or complete, just as we cannot be sure that the judge was as impartial as he is made to appear, or that the women really were given the opportunity to ‘confess’.

I have not withheld facts for the sake of spinning out this yarn. I would really like to know what Browne said and thought – about the case, about the medical and bedevilled condition of the defendants, about witches in general, and for that matter about the plaintiffs and their motives. But the suspect nature of the trial record, and the absence of any discussion in Browne’s own hand, forces me to reflect on our own time. It makes me realize we cannot be sure even of what goes on in today’s criminal justice proceedings and inquiries into strange practices. All records, however authoritative, are necessarily incomplete and approximate. The words in print do not represent exactly what was said and what was said never represents exactly what was meant or taken as meant.

How Browne would have smiled at my difficulty. Uncertainty was his stock in trade, and judging between uncertainty and unknowability his unique talent. This readiness to mark out a realm for the mysterious no doubt stems from a proper God-fearing humility, but I think it also shows that Browne has identified an arena for delight. He recognizes, as many, especially scientists, do not, that description is not the key to understanding all. Words cannot transmit the truth; in fact, they put layers between us and the truth. Browne’s genius was not only to accept this, but also to revel in it, finding in language not a constricting cage but a bird ready to take flight.

At Scole I turn northward and cross the River Waveney into Norfolk. Still scarcely halfway to Norwich, my legs ache and my knuckles are chilled. I note with longing the imposing brick inn at Scole, new in Browne’s day, where he may have rested for the night.

A kingfisher flashes by. One of the odder beliefs that Browne addressed in his catalogue of ‘vulgar errors’, Pseudodoxia Epidemica, was that a dead kingfisher makes a good weathervane. He calls it a strange opinion, but notes that it was nevertheless a living custom. Then he does a very Brownean thing: he tries it for himself. He procures a dead kingfisher, rigs it up, and finds . . . that it doesn’t work. ‘As for experiment,’ he reports, ‘we cannot make it out by any we have attempted; for if a single King-fisher be hanged up with untwisted silk in an open room, and where the air is free, it observes not a constant respect unto the mouth of the wind, but variously converting, doth seldom breast it right.’ Not convinced? Well, then he goes on to suspend two of the unfortunate birds and finds that as often as not they point in opposite directions.

It seems that Browne was not present at the stage in the trial at which the afflicted children were brought into contact with the accused women to see what effect they truly exerted. Here, surely, he would have been given pause for thought. For this direct empirical evidence flatly contradicted the idea that Denny and Cullender had any unique powers. Yet, predictably enough, even this further revelation was to be twisted into further evidence for bewitching.

At length, after cresting a number of hills that might have seemed gentle at the start of my ride, I see the spire of Norwich cathedral pricking the horizon ahead of me. I am relieved that my journey is nearly over. Thomas Browne, too, must have felt glad to be nearing home at last, and may have rejoiced for more a particular reason than I at the appearance of this symbol.

The Christian faith was a central and considered feature of Browne’s life. In one way, it entirely explains and excuses his belief in witches. The women’s indictment at the assize formally invoked the devil, and belief in the devil was a necessary concomitant of belief in God. He did not need to have seen a witch, or to see witchcraft being performed, in order to believe in witches. They were an article of faith.

However, in the end this is not enough. Browne is in fact surprisingly selective when it comes to what he believes in the Christian story. In his Religio Medici of 1643, the essay in which he seeks to square his scientific rationality with his faith, he finds numerous points of disagreement. He does not believe in the literal truth of Noah’s flood, for example, citing the existence of American species not described in the Bible in his refutation. His scepticism in other matters leads us to wish he had been equally sceptical about the truth of witches. Notwithstanding the presence of the two women in the court, did Browne actually ever see a witch? For remember that although he had spoken of witches, and clearly indicated his personal belief in their existence, he does not appear to have made any comment on the demonic status of the accused. Were his skills of scientific observation and experiment ever tested in this way? How would he tell a witch if he did see one? He saw ‘bewitched’ behaviour, but he never describes having seen a witch.

This doesn’t matter, though. The girls in the courtroom had clearly been bewitched, and they had accused Denny and Cullender of the crime, and that was pretty much an end of it. Browne may simply have left Bury satisfied to know that justice had been done and that he had done his duty by the Church and by the state – to king and country, as he might have reflected with quiet satisfaction in these months following the restoration of the monarchy. Although he personally never doubted the existence of witches, he was nevertheless quite capable of doubting the legitimacy of accusations of witchcraft. But on this crucial occasion he had not found it necessary to do so.

Thomas Browne is my obsession. He stands at the gates of modern science and yet remains happily in thrall to the ancient world and its mysteries, and he writes in intense colours about both of them. He is, I believe, insufficiently known and unjustly neglected. As a literary figure, he is now less well known than his admirers, who include Samuel Johnson, Coleridge, Melville, Poe, Emerson and Dickinson, Jorge Luis Borges, and, in this century, W. G. Sebald and Javier Marías. This is not, admittedly, a roll call of the most read – it is not Dickens, Hemingway, J. K. Rowling – but it does reveal some powerful affinities. ‘Few people love the writings of Sir Thomas Browne,’ said Virginia Woolf, ‘but those who do are of the salt of the Earth.’ Who would not want to join this elite?

His essays are one of the glories of the English language, but he also changed the way we use it. He invented essential words such as medical, as well as precarious and insecurity and incontrovertible and hallucination, words that speak with new precision of the coming struggle to distinguish the real from the imagined and the true from the doubtful. Was the existence of witches as incontrovertible as Browne thought? Or were the children at the Bury trial merely the victims or perpetrators of a kind of mass hallucination?

As a scientist, Browne is still less favoured. His investigations were too marginal – he was never a fellow of the new Royal Society – and too much directed towards building his own literary edifice. Among scientists today, the evolutionary theorist and writer Stephen Jay Gould was an admirer, but Richard Dawkins certainly is not – he can’t tolerate Browne’s readiness to believe in things that can’t be shown. And that too is perhaps a clue as to why we should like Browne more.

Since I came across him, while writing about the symmetrical buckminsterfullerene, Browne has never quite left me. I find he resurfaces at moments that have nothing in common except their unpredictability. He has haunted me, and now, I have decided, it is my turn to haunt him. I will try to show why Browne means so much to me and why he should mean more to all of us.

This is not so much an attempt to piece together a biography of a forgotten master of English literature and science. His life is poorly documented, and in the end, it is his own writing that remains the best place to look if we are to reveal his life of tolerance, humour, serenity and untiring curiosity.

I want to do something a little different. These qualities of Browne’s are qualities we need in greater abundance today. Browne’s preoccupations – how to disabuse the credulous of their foolish beliefs, the meaning of order in nature, how to achieve a reconciliation between science and religion, how to think about death and life – are our preoccupations. In the twenty-first century, they are often the focus of dogmatic debate that generates heat but little light. Thomas Browne’s spirit could teach us how to think more generously about these things. I want to transport that spirit into our present, which is beset with its own conflicts and areas of darkness no less than Browne’s seventeenth century.

As I rest my bike at last against the wall of the sandwich shop that now occupies the site of Browne’s house just off the Market Place in Norwich, I feel strongly that Thomas Browne is a sympathetic subject. I love the way his mind works and I love his writing. I feel I would like to have known him. I would have submitted gladly to his professional ministrations, and listened keenly as he distracted me with his latest musings. And yet he presents a problem, too. I cannot easily condone his actions at the Bury assize, neither from the standpoint of the present, nor even, I believe, from that of his own time. If Browne is to be the hero of my book, he is off to a poor start. If he is a scientist, why is he sometimes so infuriatingly unscientific? If he is a man of faith, why does he plainly doubt so much? And if he is, as he implies in Religio Medici he might like to be thought, a ‘champion for truth’, then what is truth?