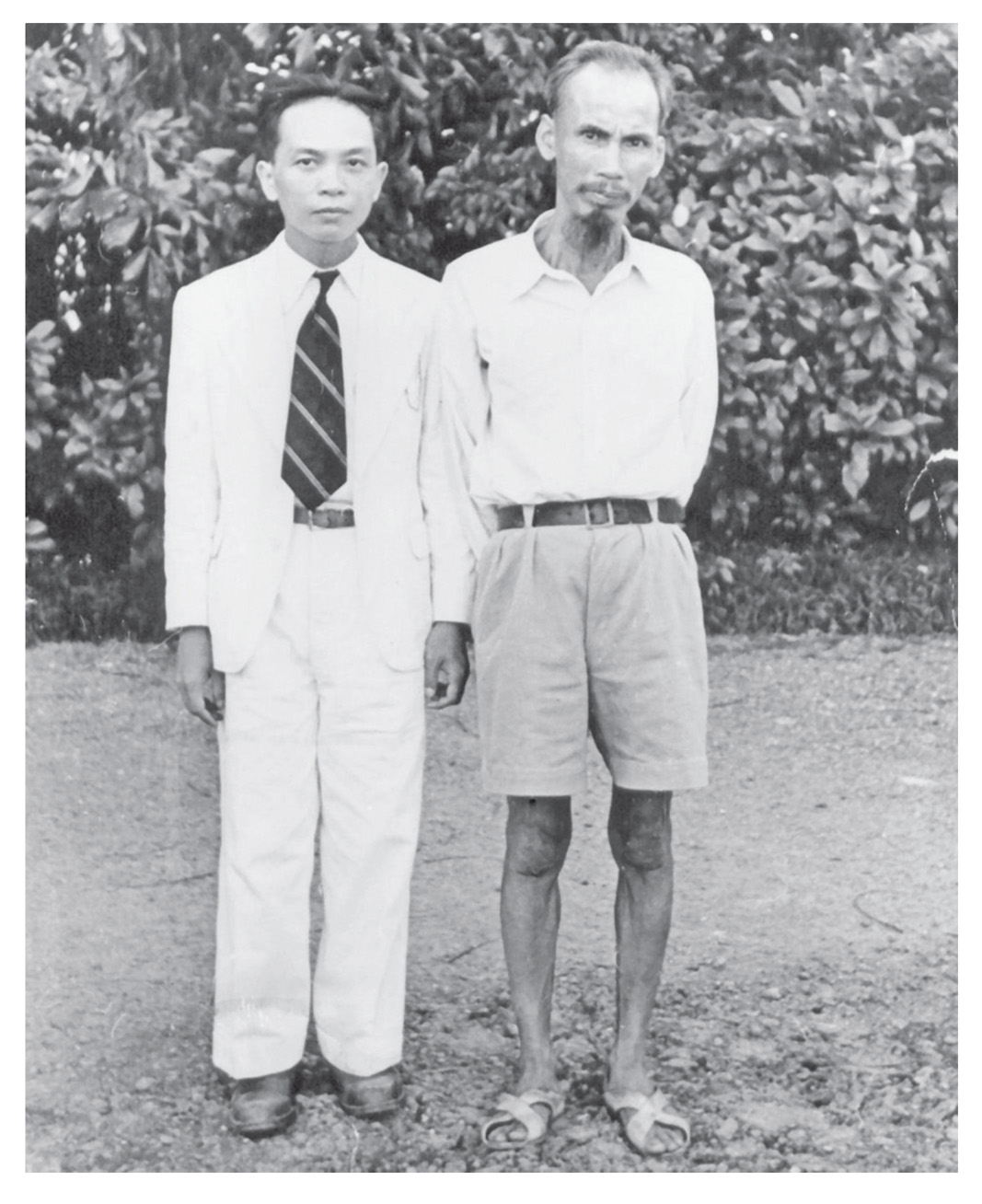

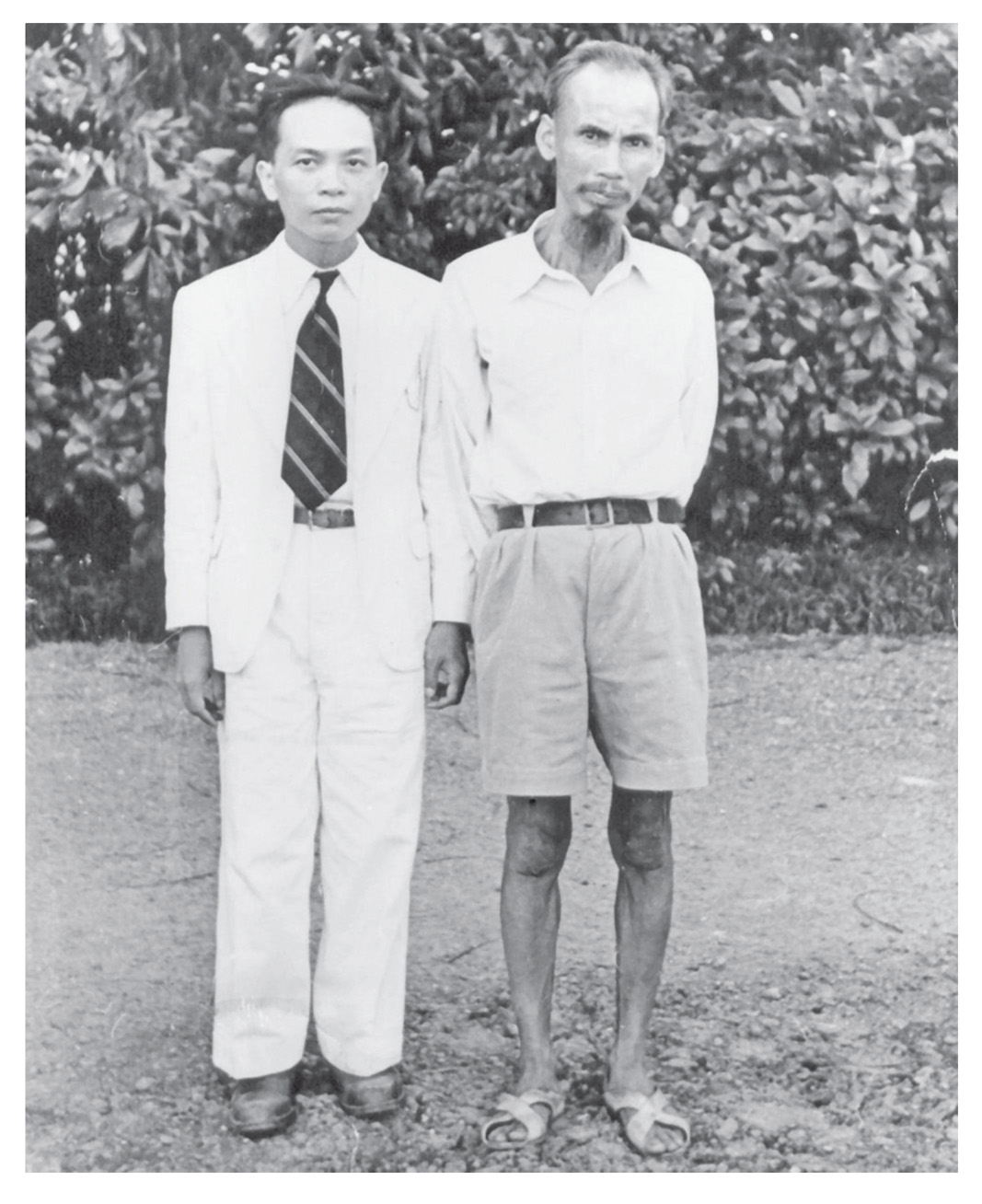

Vietnamese communist leaders Vo Nguyen Giap (left) and Ho Chi Minh, early 1940s.

France saw the opening stages of the Cold War as early as 1944 when Charles de Gaulle’s Free French Forces moved to block French communists from seizing power in Paris, Marseilles and Toulon. He had not wanted them forming a rival government that would challenge his power base. At the end of the war, the Red Army remained in Eastern Europe, occupying Hitler’s war gains. As a result, all Eastern Europe ended up with communist governments.

In Greece, following liberation, Britain was forced to act against a communist takeover. Beyond Europe, by 1949 the Chinese Civil War had ended, with Mao’s communists in power. This encouraged fledgling communist movements in Indochina, Burma, Malaya and Korea.

Unfortunately, in the post-war period, France proved more unstable than any of the defeated powers. The effect of France’s devastating collapse and subjugation in 1940 was long lasting and could not easily be remedied. The war gave rise to a strong leftwing revival, thanks to the resistance, local liberation committees and militant unions.

Vietnamese communist leaders Vo Nguyen Giap (left) and Ho Chi Minh, early 1940s.

Regrettably for France, the right wing was discredited and was unable to govern without being tainted by the past. This was unlike West Germany, or Italy, where there emerged a new and strong Christian Democratic Party.

The weak French Third Republic had been swept away, and in 1946 the Fourth Republic began but without de Gaulle. While America was relieved that he had gone, the last thing it wanted was to see France in the grasp of the communists who were aligning themselves with Stalin. At first, a coalition government between radical, socialist and communist parties was attempted, but this quickly collapsed in disarray in 1947.

After the resignation of de Gaulle, drafting a new constitution proved far from easy. After two referendums, it was finally accepted, but turned out to be very much like that of the Third Republic. It suffered the same defects and was very unpopular. It was voted in by 9.1 million to 7.9 million, but with 7.9 million abstentions. The French despaired at all the infighting, and longed for a strong government that could steer France onto the road to recovery and her rightful place in the world.

The country now experienced a swing back to the right. De Gaulle formed the Rassemblement du Peuple Français (Rally of the French People) to gather the right to the new Popular Front government. The party performed well in the local elections. An energized de Gaulle toured the country, making rousing speeches. On 15 July 1947, he told a crowd of 60,000 at Rennes that the war in Indochina and the rising nationalism throughout the French Empire was the fault of both the communists and a regime too weak to control them.

The subsequent elections of November 1948 confirmed France’s swing away from communism. The communists were excluded from the government, which fought off repeated left-wing challenges.

Elsewhere in Europe, the Soviet Union’s belligerent blockade of West Berlin during 1948–49 heralded the long Cold War between the Western Allies and the Sovietinfluenced states to the east. While America had no desire to help Britain and France recover their empires, it had no intention either of tolerating the spread of communism. From Washington’s perspective, there was no democratic peace dividend at the end of the Second World War. In Eastern Europe, communist governments had been voted in thanks to overbearing support from Moscow. In the Balkans, both Albania and Yugoslavia had been taken over by their communist resistance movements, while Greece had only just been saved following a protracted civil war.

By far the most momentous and newsworthy event in Asia was Britain relinquishing control of India in 1947. It signalled to the world that European imperialism was no longer sustainable on such an enormous scale. While the Indian communist party had on occasions been a nuisance, it was never a major player within the independence movement. Together with other political organizations, it had been subject to intense scrutiny by Britain’s secretive Indian Political Intelligence organization. Surveillance was also maintained on British communists who supported Indian nationalism.

During the Second World War, although the Indian communist party was implacably opposed to British rule, it wanted to do nothing that would aid the Axis powers. Afterwards, in February 1946, when part of the Indian navy mutinied in Bombay, the regional communist party called a general strike. As a result, violence flared, leaving over 200 dead. Fortunately for the British, Mohandas Gandhi had no interest in communist ideology or its predilection for violence. ‘India does not want communism,’ he said with heartfelt conviction. Although India was never under threat from communism, just three months after the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, Mao swallowed Tibet without much fuss. Resistance by the Tibetans was short-lived and the Indian Army did nothing to help.

It was Stalin’s Red Army that crushed Japan’s forces in Manchuria and Korea at the end of the Second World War, not Mao Zedong’s communist People’s Liberation Army. When the Chinese Civil War was renewed, Mao continued to promote communism beyond his country’s frontiers. There was a communist rising in newly independent Burma in 1948, which continued to be a threat until the fall of their stronghold at Prome two years later.

The presence of Chinese nationalist troops in northern Burma also caused the country problems. Chen Ping in Malaya, the communist leader there, after visiting Mao, employed his revolutionary methods of guerrilla warfare. The violence there also began in 1948, continuing for many years until the British and her Commonwealth allies prevailed against a weakened, predominantly Chinese insurgency.

In the case of Burma, the communists were split into two factions, known as the ‘Red Flags’ and the ‘White Flags’ that had differing goals. On Independence Day on 4 January 1948, the former was already in open revolt, while the latter followed suit two months later. Their area of control was steadily expanded from the Irrawaddy Delta all the way to Mandalay. To complicate matters, part of the Burmese army revolted, as did the country’s Karen people in the southeast, who lived along Burma’s frontiers with China and Thailand. In the face of Mao’s growing victories, Chinese nationalists, some 12,000 strong, moved into part of Burma’s Shan state on the eastern frontier. They were supplied by America and Nationalist Taiwan, in the hope that one day they would return to fight communist China. During 1950 and 1951, the Burmese launched a series of operations against the communists and Karen, greatly reducing their areas of control.

In Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh (born Nguyen Tat Than, then called Nguyen Ai Hoc) had been a communist agent since 1925. While studying in France, he had become a member of the French Communist Party, before returning to Indochina in 1930 as a representative of the Comintern (Kommunisticheskiĭ Internatsional – Communist International). His army, the Viet Minh, formed in 1941, had received training in guerrilla warfare in Yenan from Mao. By 1949, the French had been forced to recognize Vietnam as a political entity, but refused to accept Ho as ruler. Mao recognized him the following year. De Gaulle felt that it was absurd to negotiate with Ho Chi Minh and that it was vital to hold onto Indochina. France needed to send out a strong message that it would protect its colonies even when they were as far away as Indochina.

Mao’s triumph in China in 1949 meant it was inevitable that he would throw even greater resources into supporting communist movements in neighbouring Indochina and Korea. The division of the latter at the end of the Second World War, between the communist North and the supposedly democratic South, was a highly dangerous flashpoint. When North Korea invaded the South, the Americans and British, under the auspices of the United Nations, stepped in and found themselves dragged into a three-year conventional war.

In late 1949, the victorious Mao had visited Stalin in Moscow before they signed the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance and Mutual Assistance. Mao returned home, confident that China was now a full member of the international communist brotherhood.

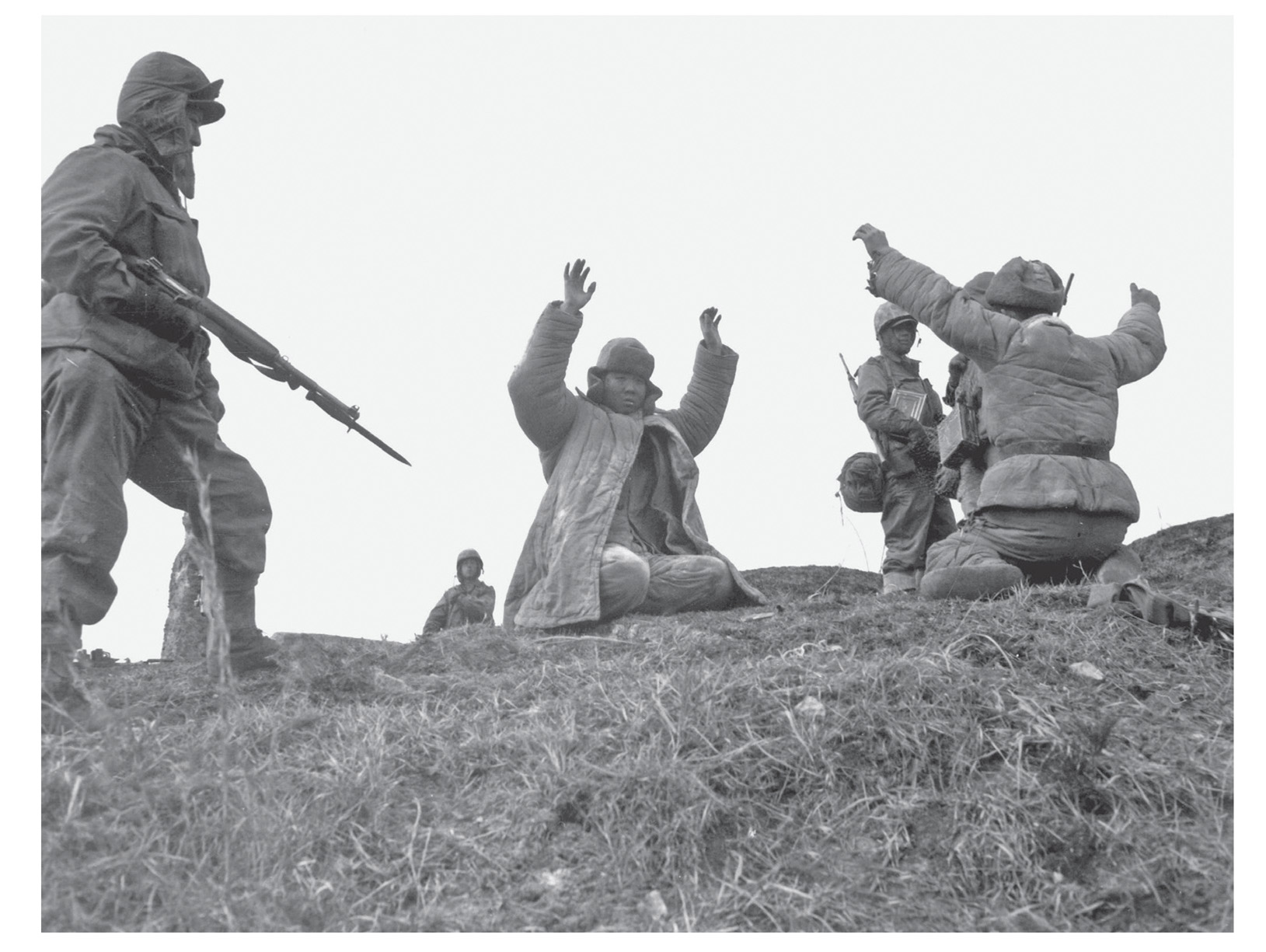

Chinese troops captured in Korea.

He was to gain the full cooperation of one of the world’s superpowers for the next thirty years. In reality, Stalin distrusted the long-term goals of communist China as it posed a potential threat to the Soviet Far East. All the time that China had been weakened by unrelenting civil war and Japanese aggression, she had not been of any great concern.

As well as tying China to the Soviet Union, Stalin needed the cooperation of the Chinese for the expansion of communism in the region. This would ensure that Mao was preoccupied and would be prevented from meddling in Soviet affairs. Mao had intended to demobilize part of the People’s Liberation Army, but he was soon to find he had need of its services again.

In March 1949, Korean communist leader Kim Il Sung had suggested to Stalin in Moscow that Korea should be forcibly reunified. At the time, Stalin was still fully occupied with the Berlin crisis, so the situation was not yet ripe for a war in Korea that could antagonize the Western powers further. Kim renewed his request a year later. This time, Stalin relented, promising military aid for the Korean People’s Army. Stalin, though, had insisted that Kim get Mao’s approval as they were about to start a major war on China’s very doorstep.

Stalin’s developing Cold War goals were self-evident: the subordination of Mao’s aims to a dominant Soviet foreign policy, the integration of a war in Korea into his East Asia strategy, support for Ho Chi Minh’s communists in Indochina, and the infiltration of the communist party in Japan. This policy of deliberately creating flashpoints was designed to force America to stretch her defence commitments at a time when she was demobilizing. This inevitably would force Washington to reduce its support for the 1949 North Atlantic Treaty Organization in Europe. Stalin would deliberately extend the Cold War from the escalating standoff in Europe, to one of global confrontation that included Korea and Indochina.

The British Joint Intelligence Committee, in fact, assessed that the Korean War was not part of the Cold War in Europe, saying:

We believe North Korean aggression was originally launched not with the primary objective of diverting American attention from Europe, or as a prelude to provocative action against our weak spots on the European or Middle East periphery, but as a limited operation within the gambit of an intensified drive to expel Western influence from the whole of the Far East and South-East Asia.

America played right into Stalin’s hands when it announced that the U.S. Pacific defence perimeter ran from the Philippines to Okinawa and then back through Japan, but crucially excluding Korea. In January 1950, the Americans confirmed the exclusion of Korea and Taiwan. This gave Stalin almost a free hand to help Kim Il Sung.

While Soviet troops would not be directly involved in the invasion of South Korea, Stalin promised that Mao would release 14,000 battle-hardened Korean soldiers who had served with the People’s Liberation Army. In total, around 100,000 Koreans had fought alongside Mao’s forces in China. Stalin also promised advisers and weapons, in particular tanks, which was something the South did not have. The plan was to occupy South Korea in a two-week operation.

Stalin and Mao, however, made a strategic miscalculation, for they took the Americans at their word that they would not defend South Korea. However, with American bases in nearby Japan, it was relatively easy to feed troops into Korea. The two communist leaders would have been better off toppling the weak French hold on Indochina. The French military did not have the resources to fight a war across Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Should the Americans have decided to intervene to assist the French, their nearest bases were much further away in the Philippines.

Mao’s commitment to the Korean War, including vast numbers of Chinese troops, was a fortunate development for Paris. It meant that Chinese support for the nationalists in Indochina would diminish, plus the international community would be distracted whilst it supported United Nations forces committed to the defence of South Korea. For Ho Chi Minh, it represented a significant setback. Despite the enormous burden of the war in Indochina, the French sent an infantry battalion to South Korea, which landed at Pusan on 29 November 1950. It was to remain for the next three years until redeployed to Indochina.