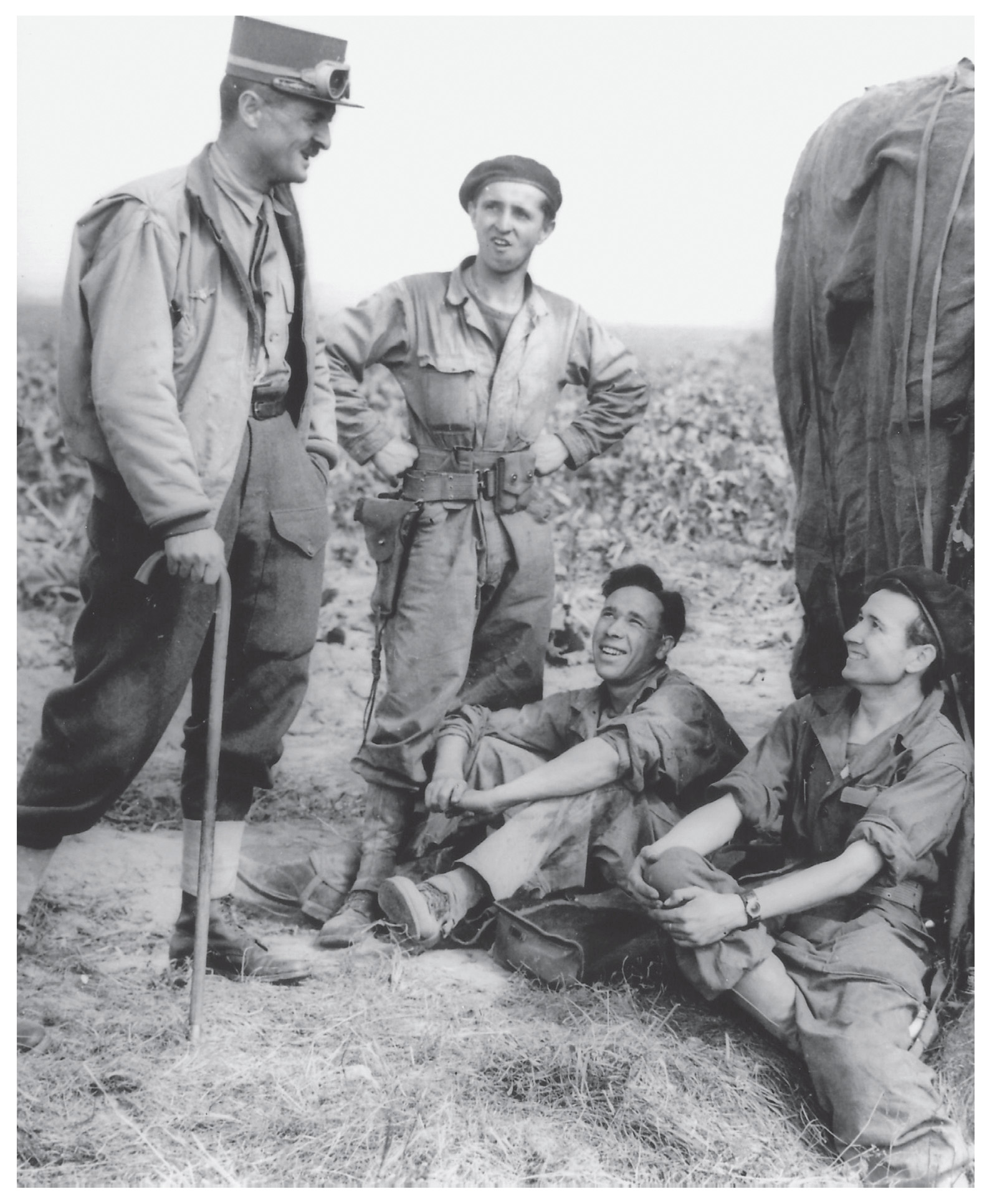

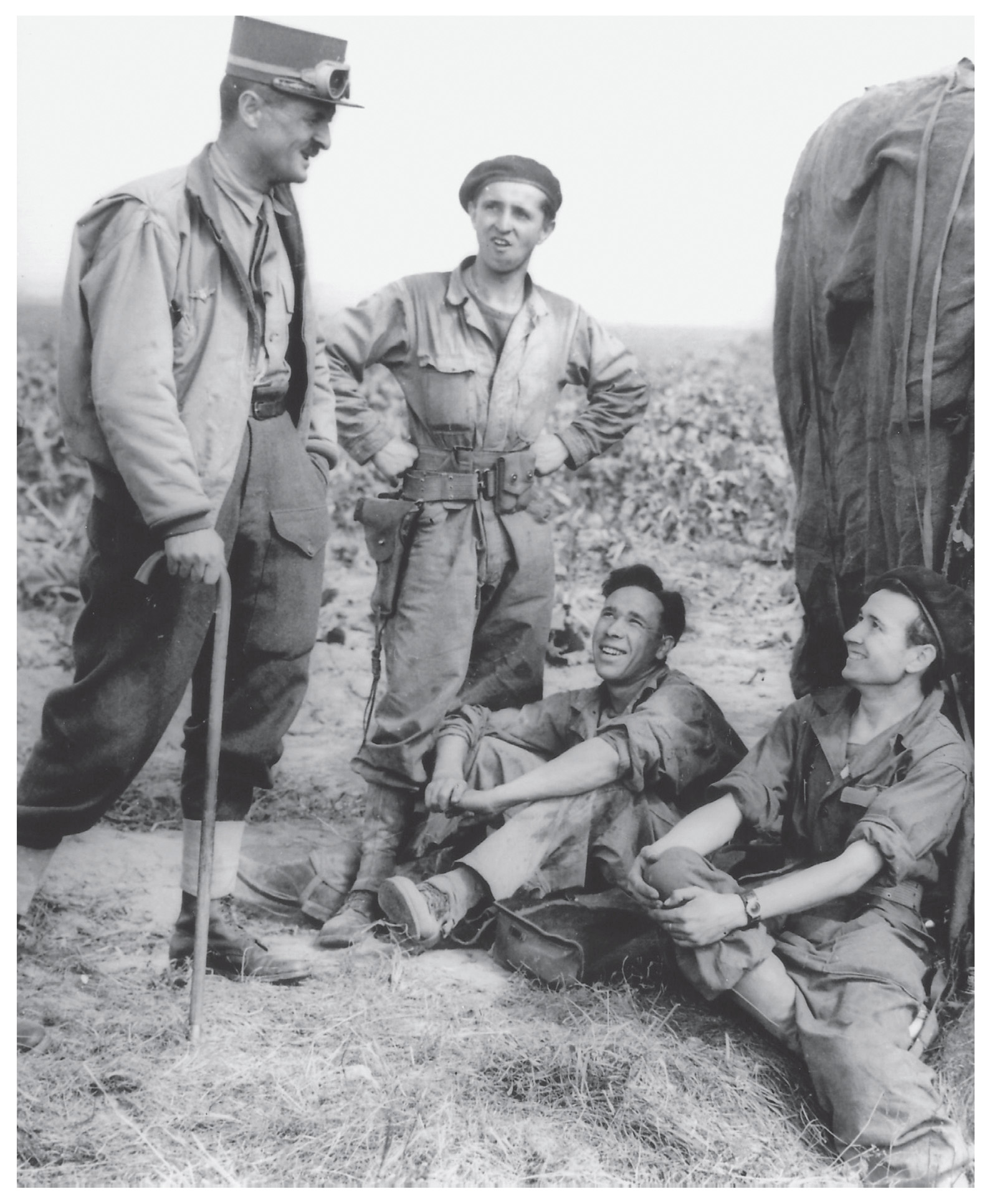

General Leclerc, seen here with some of the men of the French 2nd Armoured Division, 1944.

Thanks to British assistance, General Leclerc, with his limited forces, managed to successfully reclaim southern Indochina for France. In early 1946, he began to plan for an amphibious operation to get his men into the port of Haiphong and then onto Hanoi. He was well aware that the position of the 30,000-strong French community in the north was precarious, as they were caught between volatile and competing parties. Beforehand, much diplomacy was required to ensure his men were not opposed.

Leclerc urged Paris that the time was ripe to promise independence for the nationalists within the French Union. He reasoned, after his military landings at Haiphong, that France would have recovered sovereignty throughout the bulk of Indochina, and only such a step would appease the nationalists. His concern was that if this did not happen, he would be confronted by a protracted guerrilla campaign that he did not have the resources to fight.

Leclerc, as military commander, did not have the best of relations with High Commissioner d’Argenlieu. The latter refused to discuss overall strategy with Leclerc, insisting that his role was purely to reassert military control and not worry about the peace settlement. During the negotiating process in early 1946, Leclerc often found himself side-lined. To make matters worse, after the resignation of his sponsor, de Gaulle, he did not get clear support or direction from Paris. D’Argenlieu, influenced by local colonial administrators and residents, was of the view that a show of force would secure outright military and political victory.

In the north, there remained the thorny issue of the Nationalist Chinese and Viet Minh. Leclerc knew that once the Chinese had agreed to leave, he would have to move swiftly to secure Hanoi. At first it appeared as if the French and Viet Minh could reach a compromise. To appease the Chinese, Ho Chi Minh’s government included non-communist nationalists, and in November 1945, he even, publicly at least, dissolved the Indochinese Communist Party.

In the face of the British withdrawal from Saigon on 6 March 1946, Ho Chi Minh signed an agreement with the French administrator, Jean Sainteny. Ho agreed to allow 25,000 French and French-officered Vietnamese troops into the north’s urban areas. Sainteny recognized Vietnam as both a ‘free state’ within the Indochinese Federation, and as part of the French Union, and Paris agreed to withdraw all troops within five years, except for those at a few bases. A referendum was to be held on the unity of Vietnam in Tonkin, Annam and Cochinchina.

Leclerc felt that this was a step in the right direction, and d’Argenlieu, who was in Paris, could not interfere. Both sides, though, knew that this agreement was really just to facilitate the removal of the troublesome Chinese. Leclerc appreciated that, long-term, Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh were wholly opposed to French control.

At the start of the year, Leclerc developed a three-point strategy to remove the Chinese, who were not popular with the local French or the Vietnamese. However, the Chinese nationalists had no intention of letting the communists take power in Tonkin and northern Amman. They backed local opposition to Ho Chi Minh, which had obliged him to recognize Sainteny’s authority. Therefore, it was vital that Paris exert diplomatic pressure on Chiang Kai-shek, as well as Leclerc’s own officers on the Chinese command in Hanoi, to facilitate the withdrawal. Secondly, Leclerc wanted to build up his forces sufficiently enough so that they were a factor at the negotiating table, and thirdly, talks should be opened with Ho Chi Minh. By early 1946, the total number of French troops had risen to 65,000.

General Leclerc, seen here with some of the men of the French 2nd Armoured Division, 1944.

Chiang agreed to allow his army in Tonkin to be progressively relieved by French units during March 1946. In any case, he needed his troops home to redeploy against Mao’s Communist guerrillas, but he used the situation to get the French to relinquish their concession in Shanghai. In Hanoi, General Salan and Sainteny negotiated with General Lu Han to accept this timetable. These talks proved problematic with the Chinese, who appeared not entirely keen to leave their new fiefdom. They would not depart until April 1946 at the earliest, which posed problems for Leclerc, whose forces were to land in Haiphong during the first week of March. This meant that he could not be sure until the very day of his landings whether the Chinese would choose to resist.

Just as he feared, on the evening of 5 March 1946, when his force entered the Haiphong River, local Chinese units opened fire. One landing ship was set ablaze and others were hit. Leclerc had no option but to respond. A thirty-minute firefight ensued, as the two sides needlessly shot at each other. The Chinese, deciding that honour had been served, sent a negotiator with the offer of a ceasefire on condition that the French withdrew downstream. Leclerc refused, and a very tense twenty-four hours followed, until the Chinese finally allowed him to disembark 5,000 troops.

The day after the landings, Giap came to see Leclerc to press his case. As fellow soldiers, both showed the other great respect, with Giap offering admiration for the French resistance and the liberation of Paris. Not long after Leclerc met with Ho Chi Minh, the communist leader was impressed with Leclerc whom he felt he could trust. Ho wanted a joint Franco-Vietnamese commission to supervise the ceasefire and administration of south Annam and Cochinchina. Leclerc refused on the latter, but agreed to scale down French operations while contact was made with remaining rebel units. He also supported Ho’s call for early negotiations with Paris, which were backed by the pragmatic Sainteny.

Although the rest of Leclerc’s force landed without further hitch, another week was wasted while pressure was brought to bear on Chiang Kai-shek. Eventually, the local Chinese commander agreed to coordinate his withdrawal with the French. The Tricolore was flying once more over Haiphong, but at the cost of thirty-seven dead.

Despite this apparent progress, when Leclerc entered Hanoi on 18 March 1946, only French citizens welcomed him. In some areas in Tonkin, the French were met with outright resistance, but in others, Leclerc and Salan managed to develop a friendly partnership with the local Viet Minh. Leclerc knew that with his limited resources the complete re-conquest of Tonkin was simply impossible.

Keen to avoid French involvement in purely internal Vietnamese affairs, and to foster cooperation, Leclerc was soon at loggerheads with d’Argenlieu. The High Commissioner was not prepared to make any concessions. He felt that Leclerc’s meetings with Ho and Giap verged on national betrayal. D’Argenlieu was of the view that Leclerc and Salan were straying well beyond their military remit, ignoring the fact that the generals were on the political as well as military frontline when it came to dealing with the communists.

D’Argenlieu, even while still in Paris, did all he could to delay the negations and sought to divorce Cochinchina from the rest of Vietnam. He used his time in the French capital to strengthen his hand and garner support for his hard-line approach. He wanted Leclerc and Salan dismissed and replaced, but he could not achieve this. When he returned to Indochina in late March, he completely ignored both generals, and began issuing orders, bypassing the military chain of command in th process.

The French transport fleet consisted largely of the French-produced version of the Junker Ju 52, the Toucan.

Leclerc was thoroughly alarmed that d’Argenlieu’s actions would inevitably push Ho further into the arms of the more militant wing of the Viet Minh. In Cochinchina, the High Commissioner’s proposals resulted in the Viet Minh opening a new guerrilla campaign that the stretched French forces could not contain. When d’Argenlieu finally met Ho, all he would offer was local negotiations – there was to be no high-level international recognition with talks in Paris. Giap responded by demanding full independence encompassing Cochinchina.

Despite his goal of maintaining French sovereignty, d’Argenlieu, in order to keep the Viet Minh talking, had to acquiesce to holding discussions in Paris. Due to the instability of French domestic politics, these were delayed until the summer, by which time d’Argenlieu had forged ahead with his plans by forming a government for Cochinchina. On 1 June 1946, he proclaimed Cochinchina an autonomous republic, in effect a French puppet state. Ho and Giap saw this as nothing more than a French attempt to foist partition on Vietnam. When Ho arrived in Paris in late June to be greeted by Marius Moutet, the Minister for Overseas Territories, it was inevitable that the talks would go nowhere.

By this stage, a dispirited Leclerc had been recalled to France, assuming that his mission had been completed, but also appreciating that he was under a political cloud because of his liberal approach to Vietnam’s nationalists. During the Fontainebleau conference, Ho unexpectedly called on him. Leclerc knew better than to criticize d’Argenlieu publicly, or offer any intervention that would ultimately do more harm than good. He was also not duped by Ho Chi Minh’s friendly ‘Uncle Ho’ persona.

Ho Chi Minh signed an agreement that September, but it did not go far enough for Giap, who resumed violence both against the French and their supporters, and even against the moderate Vietnamese nationalists. Between them, d’Argenlieu and Giap ensured that Indochina would not be spared all-out war.

To block supplies reaching the Viet Minh, and to reassert French political authority in the north, soldiers moved to seize Haiphong’s custom houses on 15 October 1946. After street fighting broke out on 23 November, the French navy bombarded the port. This reportedly resulted in the deaths of 6,000 Vietnamese civilians. There could be no turning back now. Full, open conflict commenced on 19 December 1946, with a rising in Haiphong heralding the start of the First Indochina War. It took a week of fighting to clear the Viet Minh from the city.

Leclerc immediately found himself summoned by France’s new socialist prime minister, Léon Blum, who wanted him to act as his personal representative in Indochina. There he would assess the situation and offer advice. De Gaulle warned Leclerc that this was a purely political appointment that would cause nothing but trouble, but after his first family Christmas in nine years, Leclerc flew back to Indochina.

He was in an impossible position. He had no authority to act as an intermediary with Ho Chi Minh, nor was he military commander. Likewise, his liberal approach was widely frowned upon by Paris and the colonial authorities. Leclerc knew from French history that France had faced similar situations before, under Napoleon I in Spain and Napoleon III in Mexico. He visited both north and south Vietnam and quickly recommended reinforcing the French garrison, knowing full well that France, in the face of the growing Vietnamese insurgency, would have to negotiate from a position of strength.

The American C-47 Skytrain played a key role in the Battle of Dien Bien Phu.

When he returned to France, he was offered the role of military commander in Indochina, but he declined, not wishing to work with the intransigent d’Argenlieu again. Then Ramadier, Blum’s successor, even offered him d’Argenlieu’s job.

However, Leclerc’s conditions were unpalatable, for he wanted an end to direct French provincial administration and negotiations with the Viet Minh. Also, in return for full independence within the French Union, France would retain only a limited military presence. Leclerc argued that full military re-conquest would require 350,000 troops, or 115,000 to negotiate from a position of strength. Either figure was something the French government would not agree to or fund.

Once more, de Gaulle advised Leclerc against taking the post, pointing out that the removal of d’Argenlieu would cause a loss of French prestige. In addition, Leclerc would find himself a scapegoat for all the woes of Indochina. He agreed with de Gaulle and declined the job. Leclerc remarked, ‘Colonial empires all have their period of greatness but are destined to disappear sooner or later. Let us hope that ours will disappear in good circumstances.’

It was not to be. As for Leclerc, he was sent to North Africa instead, where he found the situation not disimilar to Indochina. He was killed in late 1947 in a plane crash in Algeria. In Indochina, if the 6 March agreement had been fully honoured by Paris, the disastrous following seven years could have been avoided and the French military not set upon the road to Dien Bien Phu.

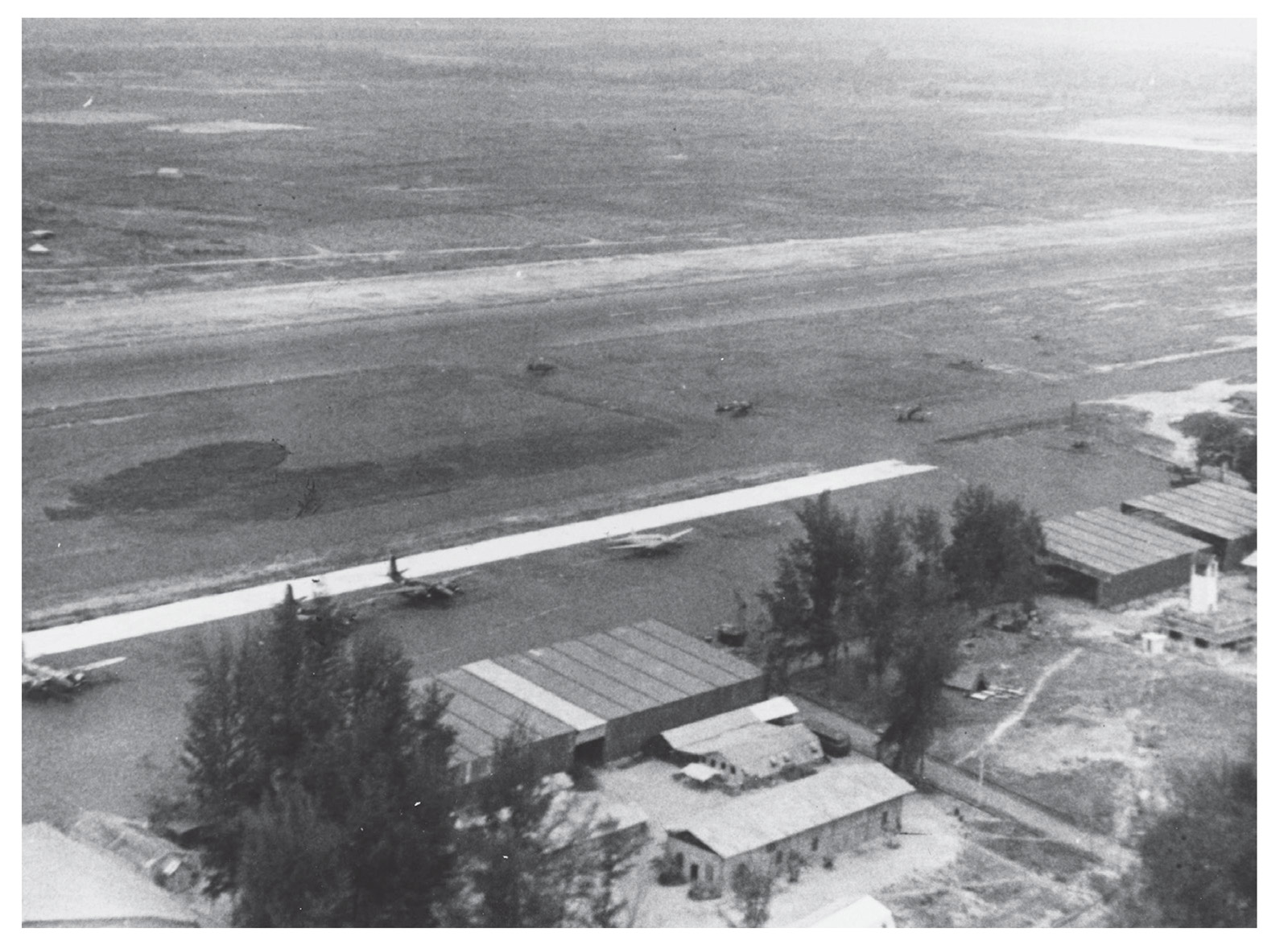

French aircraft at Tourane (Dan Nang).