Bison tanks in paddy fields engaging Viet Minh positions.

In the meantime, Giap was so close to Hanoi that he could not help himself, and decided to cut through the town of Vinh Yen just 65km northwest of the city. Once on the Red River, he could thrust southward. This, Giap and Ho assured themselves, would ensure a swift victory. They gathered a large force of some 22,000 men, comprising the 308th and 312th Viet Minh divisions. In total, there were over twenty-five battalion-size Viet Minh units. Giap, though, made the fatal mistake of making a direct assault on Hanoi without launching any diversionary attacks to dissipate French strength.

Although the French were seriously outnumbered, de Lattre prepared his defences at Vinh Yen very well. He had a thin protective screen of dug-in infantry before the town, inside there was a mobile group, while a second mobile force was deployed to the south, ready to counterattack. The first consisted mainly of North Africans, while the other comprised Senegalese and Muong tribesmen. In total, de Lattre could field only about 7,000 men.

On 13 January 1951, the Viet Minh swiftly pushed the screening French infantry back, moving into the hills between Vinh Yen and the south bank of the Red River. The French outpost at Bao Chuc was overrun without difficulty. The following day, when the first mobile group moved forward to reinforce the infantry at Bao Chuc, it was ambushed. Heavy losses were suffered, but the North Africans fought bravely and the survivors managed to pull back. The Viet Minh’s massed human-wave attacks carried them forward towards their objective.

Bison tanks in paddy fields engaging Viet Minh positions.

Despite Viet Minh fighters being within 1,000yd of the airstrip, de Lattre flew into Vinh Yen in a rickety-looking spotter plane to take command on 14 January. His chief of staff was aghast at the great personal risk the French commander-in-chief was taking and radioed his disapproval. De Lattre’s response was, ‘Well then, come and get me out.’

His presence, though, immediately boosted morale and ensured that the garrison received the resources it needed to repel the enemy. While the second mobile group moved forward, he ordered a massive airlift of reinforcements from as far south as Cochinchina. Allard, the chief transport officer, had to conduct a three-day air-and-road redeployment to bolster the defences. In the air, he could muster just fifteen elderly transports.

An opening east of Vinh Yen could have been exploited by the Viet Minh, but Giap lost his opportunity. Thanks to the vigour brought by de Lattre, and the growing strength of the French air force, the Vinh Yen defences were hurriedly consolidated, while the Viet Minh were held in the hills for twenty-four hours. When Giap opened his attack on 16 January with the 308th Division, his men were cut to pieces as they surged forward in massed human waves. De Lattre recklessly flew over the battlefield in his spotter plane, assessing the situation and directing fire.

He quickly decided to summon almost every combat aircraft available in Indochina and to commit the last of his reserves in an effort to thwart Giap. The following day, a newly formed mobile group, consisting of two Moroccan and one para battalion, joined the fight with considerable air support. The French air force played its part, dropping napalm for the first time on a large scale on 17 January to break up the Viet Minh attacks. The blistering heat incinerated those caught in the open, leaving a trail of charred and smouldering corpses. Those on the periphery, their uniforms ablaze, ran screaming until shot down, or they could roll in the soil to smother the searing flames. It was a hideous sight, but it had the desired effect.

Undeterred, Giap renewed his attack, using the 312th Division. They were stopped in their tracks by French fighter-bombers, again using napalm. Nonetheless, the pointless fighting continued well into the afternoon of the 17th. Two days later, it was all over. The Viet Minh had suffered some 5,000 casualties, comprising 1,600 fatalities, at least 3,000 wounded, and 480 captured. To his dismay, Giap had thrown away his opportunity to end the war. The French lost 43 killed, 160 wounded, and 545 missing or captured.

The Viet Minh had come very close to overrunning Vinh Yen, but that was little solace for such heavy losses. Once the French air force was committed in strength and dropping napalm, Giap should have saved more of his men by calling a halt to the attack and withdrawing. Instead, he very clearly signalled that he was prepared to sacrifice his men to achieve his goals. Giap had every faith in their morale and their commitment to the fight for independence, even to the death.

Vinh Yen provided a much-needed boost for the morale of the men of the French Expeditionary Force, proving to Paris that de Lattre was indeed the man for the job. He concluded that prepared defences, backed by mobile reserves and air power, was the best way to defeat the Viet Minh fighting a conventional war. This conclusion would shape French strategy and lead to Dien Bien Phu four years later.

During the battle at Vinh Yen, de Lattre called on Emperor Bao Dai, requesting more Vietnamese units and, with his candidate, for a new Vietnamese defence minister. Bao was not receptive, but after the French victory, he instructed his prime minister, Tran Van Huu, to dissolve the government and form a new one, including de Lattre’s defence minister candidate, Nguyen Huu Tri. In a message to the Vietnamese, Bao made no mention of the French success, while the enraged de Lattre brazenly held a victory parade in order to salute his men. The Vietnamese government soon broke down, for which de Lattre held the emperor responsible.

De Lattre, now riding high with public and political opinion, understandably renewed his call for reinforcements. He asked Paris to provide twelve infantry battalions, and five artillery units plus support. This was met with opposition and much hand-wringing over how it would be funded. The accountants went to work, seeking to make savings. After much haggling, it was agreed that he could have nine battalions and three artillery units for just eighteen months. De Lattre was probably quietly pleased because, like any good general, he would have asked for more than he expected to receive. Paris also managed to persuade Washington to provide financial aid to pay for French military purchases, especially the equipment for new Vietnamese units. The only drawback was that the money would not be available until the autumn.

Elsewhere, the successes against Viet Minh operations in Amman, Cochinchina, Cambodia and Laos, released French troops for the more fiercely contested delta area. Also, some units were replaced by the newly formed Vietnamese battalions. In Tonkin, de Lattre could muster 68,500 French Union and 18,000 Vietnamese soldiers. In stark contrast, Giap had around 170,000, including 112 battalions, each over 900 strong.

De Lattre decided to fly to Paris to press his case for more men, but twice he had to postpone his departure. The first delay was caused by the Vietnamese government crisis, the second by the fall of the Pleven government in Paris. Unfortunately for de Lattre, Pleven’s successor, Queuille, saw the strengthening of the defence of Europe as a key priority in the face of the Red menace over more costly resources for Indochina. The only alternative in Europe was the rearmament of Germany, and no one was ready for that.

Morane-Saulniet Cricket spotter plane. General de Lattre landed at Vinh Yen aboard one of these aircraft.

To compound de Lattre’s difficulties, the situation in Morocco and Tunisia was a growing cause for concern. It was at this point that his health began to decline due to painful problems with his right hip.

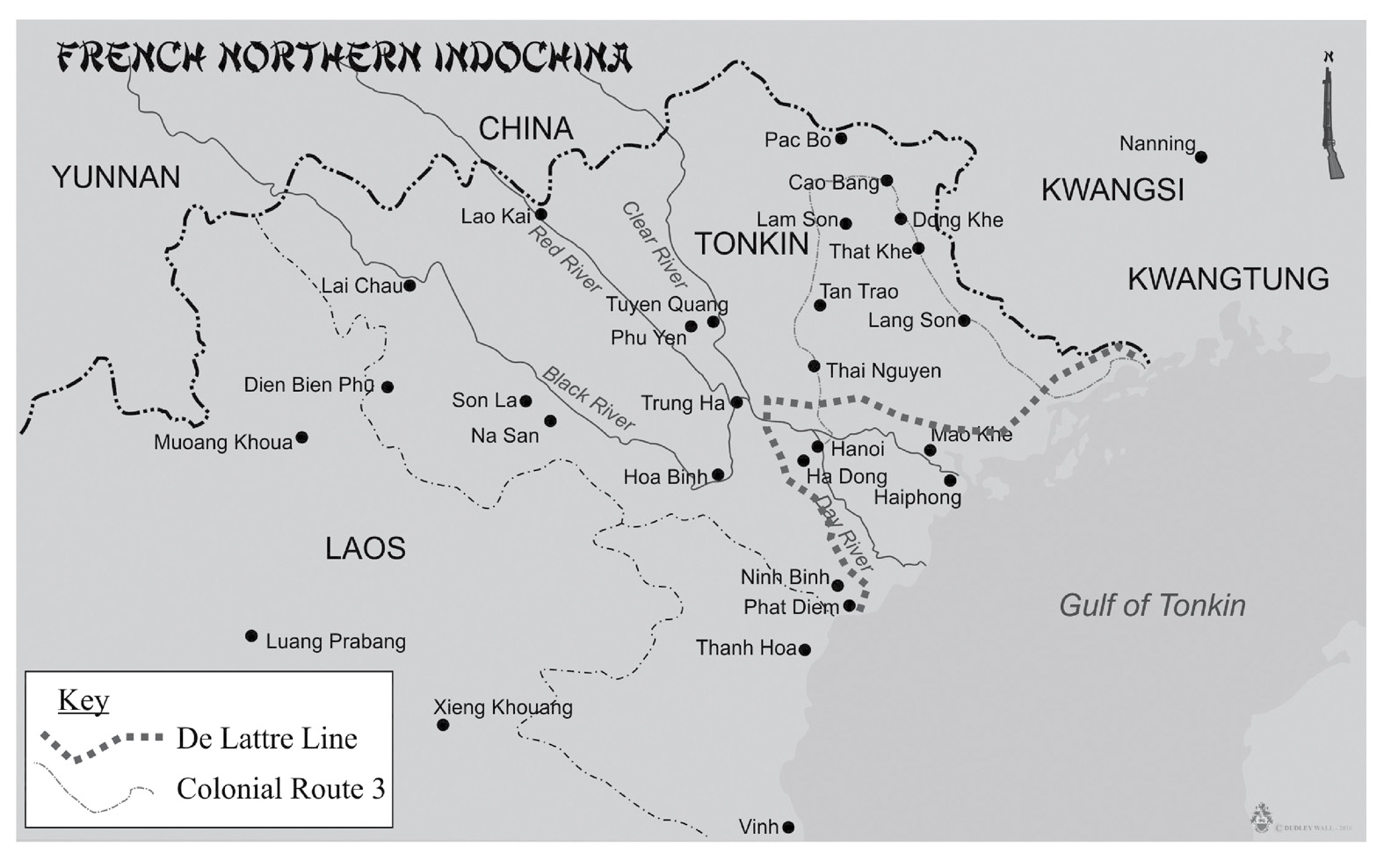

Giap was facing his own issues. The French victory at Vinh Yen had encouraged the creation of the defensive ‘De Lattre Line’ around the Red River Delta. The French set about constructing some 1,200 concrete blockhouses, running from Ha Long Bay, across to Vinh Yen, and then southeast to Phat Diem. While the rationale for these fortifications was self-evident, they signalled that the French were intent on tying down more of their troops, and that the defences were pointless if the areas behind them could not be pacified. De Lattre hoped that the blockhouses could be manned by local troops, while mixed French-Vietnamese commando units were developed as mobile strike groups to hunt down the Viet Minh. The military authorities were not keen on this combination, having little faith in the loyalty of Vietnamese soldiers.

To pre-empt the De Lattre Line, Giap had little option but to renew his offensive. As his attack to the north of Hanoi had failed, he shifted his efforts to the small town of Mao Khe, just 32km north of Haiphong. While the main attack was towards the port, it appears that the assault was to be supported by an insurgency behind French lines, intended to destabilize the whole of the delta. If Giap got to Haiphong, it would cause de Lattre major supply problems.

Giap was unable to hide his considerable preparations in the massif near Dong Trieu, which involved three divisions. His deception plans failed to work and the French were fully aware of the presence of five Viet Minh brigades (or small divisions), plus a large force of supporting coolie labour. When his assault commenced on the night of 23 March 1951, it had some success against the French outer defences. Three days later, Mao Khe was in danger as the 316th Viet Minh Division massed, ready to overwhelm the defenders. A bombardment by French naval vessels on the Do Bac River, however, caused the force to disperse, delaying the attack. On the 27th, the Viet Minh launched a massed assault on French defences outside Mao Khe. Although there were some breakthroughs, the town was held.

De Lattre arrived back in Hanoi from Paris, feeling feverish and despondent. Once briefed, he quickly appreciated that Mao Khe, as it was at the exit from the massif, was the key to the battle. Reinforcements were sent up the river, arriving just as the Viet Minh had gained a foothold in the northern edge of the town. The enemy were thrown out and their advance temporarily halted.

Night air reconnaissance, used for the first time, and other intelligence suggested that the Viet Minh had retreated and abandoned any follow-up plans. De Lattre, however, was not convinced, surmising that the Viet Minh were using effective camouflage to hide their movements. He refused to redeploy his forces at Mao Khe, electing instead to place the troops on high alert.

The U.S. first supplied Grumman F8F-1 Bearcat fighter-bombers such as these to the French in Indochina in January 1951. (Photo U.S. Navy)

Just as de Lattre had anticipated, on 28 March 1951, Giap threw his 316th Division into the assault. There was no subtlety in the attack. Human waves launched by twelve 1,000-strong units, were met by artillery, fighter-bombers and warships. Some of the attackers reached the wire, where they were mown down by French small-arms and machine-gun fire. Their bodies lay snagged in the wire like rag dolls, creating a path for those fortunate enough to have survived the deluge of firepower.

Those men who got past the wire, were engaged in vicious hand-to-hand combat. Pistols were fired at close quarter, rifles were used as clubs, bayonets as daggers. The Viet Minh were eventually beaten off with heavy losses. Afterwards, French and Vietnamese troops picked through the scattered, blood-splattered bodies. In five days of fighting, Giap’s men suffered 3,000 casualties. It was yet another French victory, thanks to superior firepower and superb defensive tactics.

De Lattre did not wait for Giap to try again. Instead, he moved swiftly to stamp out the insurgency behind his lines in the delta. He ordered his first major sweep with Operation Méduse in mid-April 1951. This, under the local command of de Linarès, and involving three mobile groups, was an unqualified success. His second, Operation Reptile, proved less successful, the French thwarted in part by the Viet Minh guerrillas’ ability to blend in with local communities at will.

Vought AU-1 Corsair fighters on the USS Saipan being delivered to the Aéronautique Navale at Tourane (Da Nang), 1954. (Photo R.H. Spanioer)

De Lattre’s forces overran training bases and propaganda centres, and disrupted Viet Minh organization. Catching the fighters, however, remained another matter. To stop the guerrillas taking up arms again required a permanent military presence. He knew he had to conduct a hearts-and-minds campaign to sway the population who were caught in the middle.

After Vinh Yen, de Lattre took the Vietnamese prime minister to the scene of the battle, where he reaffirmed that the role of the French army in Vietnam was to secure a lasting independence. Otherwise, he warned, Indochina would fall to communism. He also took great pleasure in presenting Bernard de Lattre with his second Croix de Guerre after his conduct during the latest round of fighting.

De Lattre now felt that he could take time out, so he flew to Singapore to discuss the communist threat to Southeast Asia with the British and the Americans. Whilst the latter were sympathetic to the struggle against communism in Indochina, neither offered troops, even in the event of full intervention by Mao. Both countries had more than enough of their own troubles. De Lattre was about to follow up the conference with a visit to Washington to speed up American material and financial support, when the unbowed Giap struck yet again.