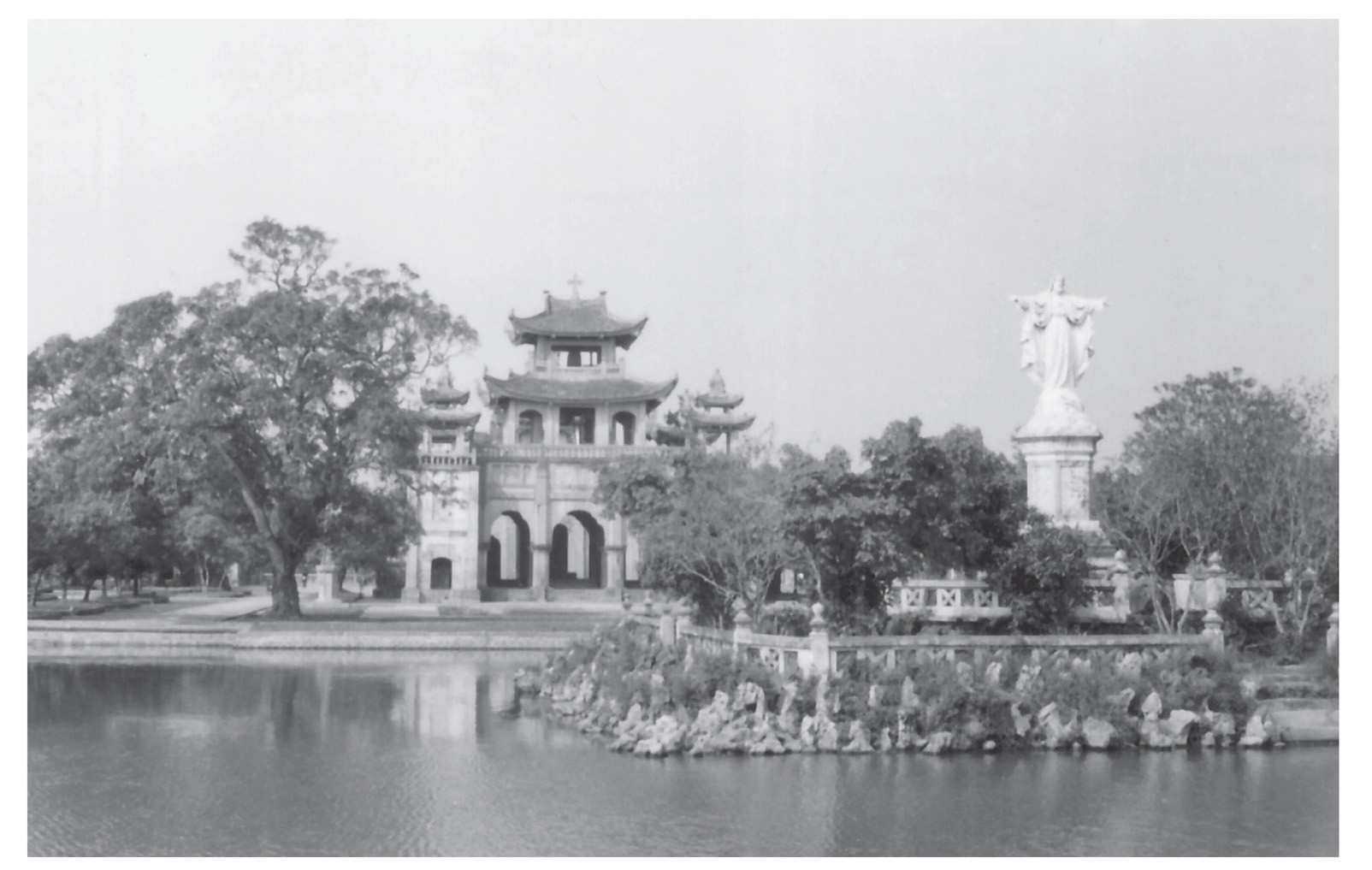

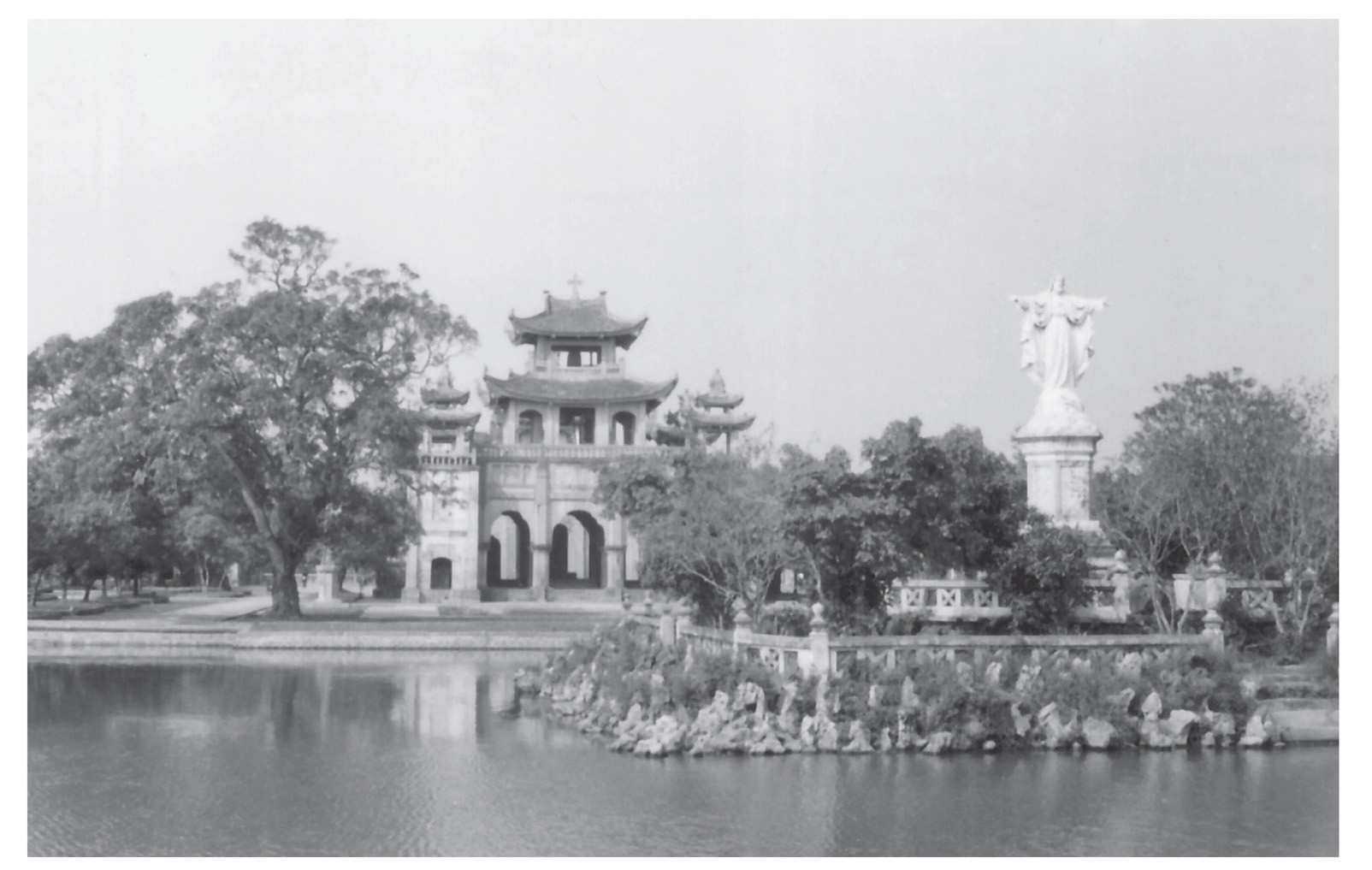

Phat Diem cathedral. The town on the Day River was the target of a Viet Minh attack in May 1951.

Following Vinh Yen and Mao Khe, Giap was forced to reassess his flawed strategy. His direct assaults on Hanoi and Haiphong had failed, so he now concentrated his efforts to the south on the Day River. If he could seize this area, it would tie down de Lattre’s reserves prior to a renewed effort on the Red River. The French commander in this area, Colonel Gambiez, was half expecting an attack, as this was a fertile part of the delta and the rice crop was approaching harvest. Giap appreciated that, this time, it was vital that the French were distracted from his main operation.

De Lattre and his commanders were therefore kept preoccupied. During April, the French had been kept busy by the Viet Minh 312th Division. This masked the redeployment of the 304th and 308th divisions, who marched to the South Delta Base to join the 320th Division. Giap planned to use them to strike at Phu Ly, Ninh Binh and Phat Diem on the meandering Day River. He proposed to repeat the tactics used for Dong Trieu, with a two-division frontal assault, and a third attacking the flank, while guerrilla operations created mayhem in the rear areas.

The weight of the attack conducted by the 304th and 308th divisions was to fall upon Ninh Binh and Phu Ly. This was designed to tie up French reserves, while, to the south, the 320th Division crossed the river at Phat Diem, linking up with a regiment that had infiltrated French lines a few days before. A move towards the coast near Thai Bin would sever the southern provinces of the delta. This would stop the French moving waterborne reinforcements north, leaving their flank exposed. In principle, it was a very sound plan.

Giap opened his operation on 29 May 1951, with the 304th and 308th divisions crossing the Day River to attack their objectives. In the process, they destroyed a number of French outposts and several gunboats. Late in the afternoon, the 320th Division also crossed the river in sampans at two points, directly opposite Phat Diem and to the southeast. Due to the rains, they soon became bogged down.

De Lattre reacted with characteristic decisiveness. Eight mobile groups and two para units met the Viet Minh. French bombs and shells rained down on the frontal assaults, soon bringing the assailants to a halt. On the water, French river patrols moved to cut the Viet Minh supply lines, sinking any vessels they came upon.

On 30 May, in his moment of triumph, de Lattre’s chief of staff brought him some devastating news. Bernard de Lattre, at the age of 23, had just been killed at Ninh Binh. He was told how his son was in his command post on a rocky outcrop with a French lieutenant and two corporals, one French and one Vietnamese, when mortar fire had rained directly down on them. All the occupants were killed or wounded. Out of some eighty marine commandos of the 3rd Naval Assault Division who also fought in defence of Ninh Binh, just nineteen survived.

De Lattre was beside himself with grief. He arranged for a Catholic mass for Bernard in Hanoi Cathedral. Two days later, he flew his son’s body home to France, an act that attracted much criticism in the French media. He and his wife held a funeral service at the Invalides. Madame Simone de Lattre requested that the service be expanded to honour the memory of all those killed in Indochina. Their beloved Bernard was buried at Mouilleron. Inevitably, the media attention on the event made the war even more unpopular in France.

Phat Diem cathedral. The town on the Day River was the target of a Viet Minh attack in May 1951.

When Field Marshal Montgomery heard the sad news, and despite their past differences, he wrote to offer his condolences. Notably though, Monty never recorded what he thought of de Lattre, making no reference to of him in his memoirs. The grieving General de Lattre, with an active combat command, was under enormous pressure. His health was beginning to fail.

Meanwhile, General de Linarès was left to finish the destruction of the Viet Minh assaults across the Day River. By 10 June, Giap had to acknowledge that all was lost. Eight days later, the last of his units disengaged and retired back across the contested river. When the French infantry and tanks re-entered Phy Lu, the river banks were a devastated, smoking wasteland. Giap’s forces suffered 11,000 casualties. He was now forced to revert to guerrilla warfare.

Ho and Giap were wrestling with some tough decisions when General Wei announced that Mao’s attention was being diverted by the forthcoming Korean War. The Viet Minh had suffered three major defeats in the past five months, losing up to a third of their regular troops, along with much of the equipment furnished by the Chinese. It was clear that conventional attacks on French outposts were no longer paying off.

To the French, these victories seemed to offer hope that the Viet Minh could indeed be defeated. The French succeeded on the Day River because they successfully cut Giap’s supply lines and because they had the support of the locals who were unsympathetic to the communists. His greatest error was overextending his forces, leaving himself without reserves. This led to some questioning Giap’s competency.

It was Nguyen Binh, in charge of Viet Minh affairs in the south, operating from the swamps near Saigon, who was made the scapegoat. He was blamed for initiating the concept of the Red River Delta operation and for not backing the Viet Minh sufficiently. In disgrace, he was recalled to Viet Bac, but never made it. Nguyen Binh was later wounded in a skirmish with the French and allegedly finished off on the orders of Giap. The latter remained in command and reorganized his command structure. Giap and his officers had little option but to re-evaluate their strategy once again, and scale down their attacks.

Upon de Lattre’s return from Paris, his first task was once more to try and supress the countryside insurgency. In reality, he was fighting a losing battle in galvanizing the Vietnamese people and the government against the Viet Minh. Massing six battalions of troops, he conducted a sweep of an area near Hanoi on 18 June 1951. This operation took place in the most appalling weather. At least one major Viet Minh unit was able to slip through the net under cover of the wind and rain.

De Lattre sought to capitalize on local sympathy for his lost son, who was killed serving with a Vietnamese unit, and to ensure that his sacrifice did not go to waste. This gave him the opportunity to appeal to potential young recruits for the local Vietnamese army. To date, attracting peasant soldiers had not been difficult, but recruiting the educated was another matter. De Lattre despaired, because this was exactly the type of young Frenchman who was giving his life for Indochina. In contrast, Vietnamese students remained unmotivated by the war.

He visited a prestigious school where he made an impassioned speech. Before a packed audience, he told the boys that membership of the French Union did not nullify independence. Without France, their country would be dominated by Mao’s China and the vengeful communists. He urged them to support Emperor Bao Dai and to fight and save their land, just as the peasant soldiers were doing. The emperor agreed to review a military parade, involving both French and Vietnamese troops. He also agreed to sign a decree officially placing Vietnam on a war footing.

In August, de Lattre took a month’s leave, as he was increasingly unwell and privately despondent about his own future. Yet his remarkable drive and energy showed no signs of flagging, and the following month he visited America and Britain. During his American visit, he met President Harry S. Truman. De Lattre’s preoccupation during these trips centred on what would happen, and in particular how would China react, once the Korean War came to an end. During his public appearances in America, and these were numerous, he was at pains to clarify that France’s war was not colonial, but part of the broader struggle against the insidious spread of communism in Asia. He cautioned that a communist victory in Tonkin would be followed by the loss of Indochina, then Southeast Asia, with the region then posing an eventual threat to India and the Middle East.

While he may have been exaggerating the situation, he knew that France could not dispense with American political support and military aid. The latter was assured but, once again, there were no offers of combat troops. After his visit to London, he spent a few days in Paris attending an army reunion and seeing old comrades. He also gained an unwelcome diagnosis regarding his long-running hip problem that had been causing him such pain. De Lattre went to his wife and told her he had terminal cancer.

Despite this crushing news, de Lattre was as tireless as ever in garnering support for the war in Indochina. On his way back, he stopped in Rome in order to lobby the Vatican to get the Roman Catholic Church in Vietnam, and its one and a half million followers, to put their full support behind opposing the Viet Minh. He landed back in Saigon on 19 October 1951, and was soon en route for Hanoi. He swiftly briefed the local Catholic Church on the Papacy’s support for the war against communism in the region. Then with his son’s death still heavily on his mind, he summoned Indochina’s leading business figures. De Lattre told them that money should be raised so that all of France’s troops, be they French, North or Black African, and Vietnamese, could enjoy Christmas.

General de Lattre, with time now running out, turned back to the battlefield with operations at Nghia Lo and Hoa Binh. While he had been away, Giap and his forces had been reasonably quiet as they were still licking their wounds. However, with the end of the rainy season, he wanted to draw the French north so that he could once again infiltrate the delta. The need to do this was urgent, as Giap’s men were short of rice and were going hungry.

In early October, Giap struck at Nghia Lo, sited on a ridge between the Red and Black rivers with the 312th Division. General Salan could not abandon this as it would open up a route to Hanoi. Thanks to the French air force and two parachute-unit drops, the town was saved. The French paras then swept an area containing some 360 villages and over 250,000 people. Once more though, the Viet Minh proved elusive and slipped away.

De Lattre wanted to bring the enemy to battle at a location that they would have to defend. He chose their supply centre at the city of Hao Binh, which was to the southwest of Hanoi and outside the De Lattre Line. To the northwest lay a place called Dien Bien Phu. Hao Binh was an important transit point between China and Amman to the south. It was also the main town in the Muong region. These people had a tradition of loyalty to the French. The town lay on the Black River, so it could be a conduit for French waterborne reinforcements and supporting naval firepower. In addition, de Lattre hoped that the taking of Hoa Binh would be the first stage of cutting the Viet Minh in two by occupying their Thanh Hoa province bastion.

The operation was under the direction of Salan and de Linarès. In the opening phase, the town of Cho Ben was attacked and secured to protect a flank. On 14 November, in a show of strength, 2,000 paras were dropped on Hoa Binh. They were followed by fifteen infantry battalions, seven artillery battalions, two armoured groups and two naval assault divisions. Giap, however, refused to give battle. He withdrew, in turn encircling the French. On the 19th, De Lattre said goodbye to the forces at Hoa Binh and handed his command over to Salan.

Officially, General de Lattre flew back to Paris for a meeting with the Grand Council of the French Union. Privately, the real reason was for major surgery on 18 December 1951. This was followed by another operation in the new year, but his condition quickly worsened. His reported last words, on 9 January, were, ‘Where is Bernard?’ Two days later he was dead.

A grateful France posthumously elevated de Lattre to Marshal of France. Among those who attended his funeral were de Gaulle, Eisenhower and Montgomery. After the service, a turretless armoured car took his coffin to Mouilleron. There he was laid to rest in a grave next to his beloved son, Bernard. De Lattre’s legacy was he had shown the world that what had been perceived as a campaign of colonial repression was actually a Vietnamese civil war.

French troops with a captured Viet Minh fighter.

In Tonkin, fighting continued along the Black River during December 1951, with the Viet Minh slowly closing in on Hoa Binh. Salan committed three mobile groups and an airborne group, but the guerrillas withdrew once more, only to return in January 1952. They managed to cut the river, leaving Route 6 as the only way to resupply the garrison. When the Viet Minh tried to cut the road by attacking Xom Pheo, they had to contend with the 2nd Battalion of the Foreign Legion’s 13th Demi-Brigade. The tough legionnaires resorted to repulsing them with a bayonet charge. It took a relief force eleven days to fight their way through to Hoa Binh. Reluctantly, Salan took the decision to evacuate rather than risk another encirclement. Under the codename ‘Amaranth’, this was successfully carried out between 22 and 24 February, under the cover of heavy artillery and air support.