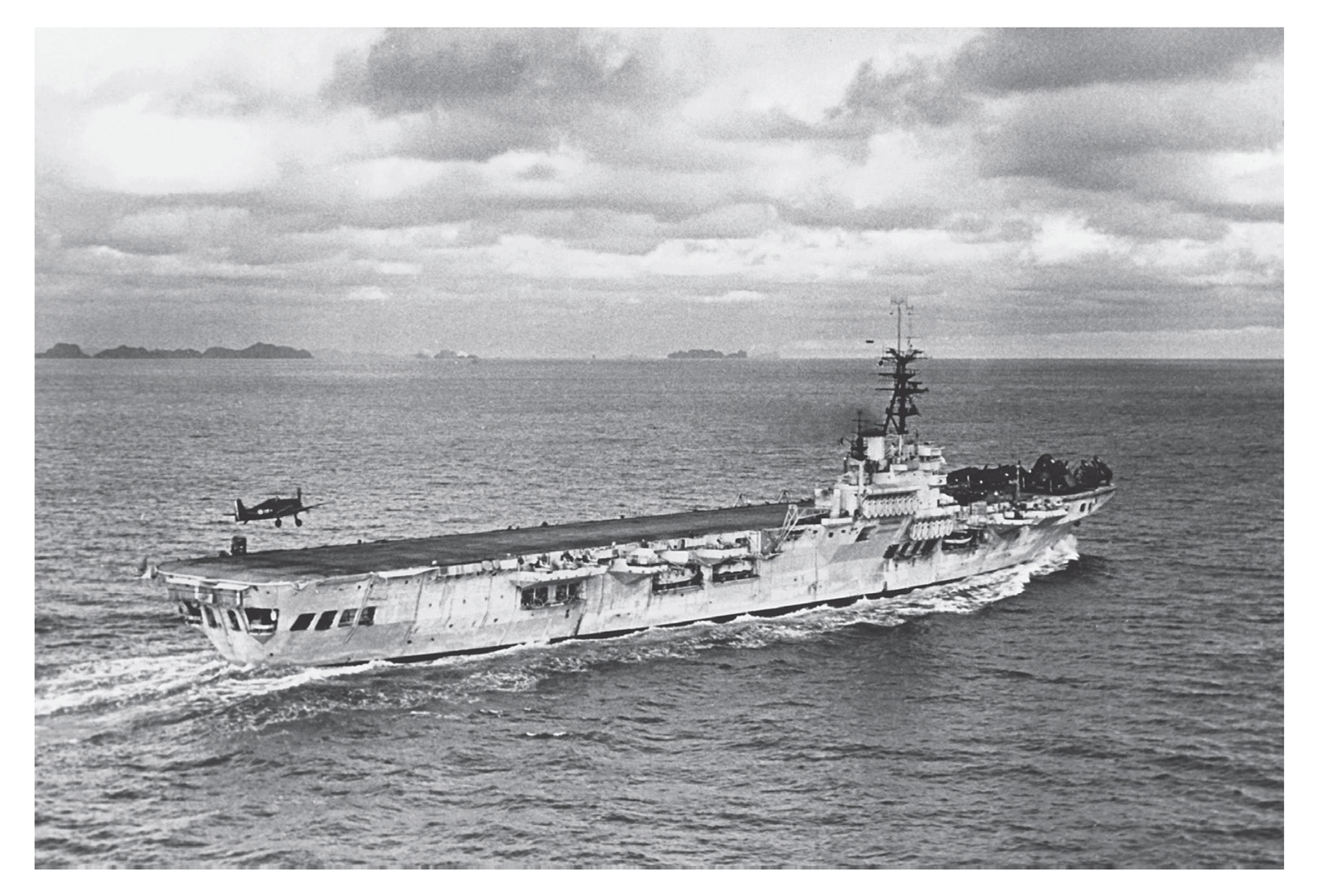

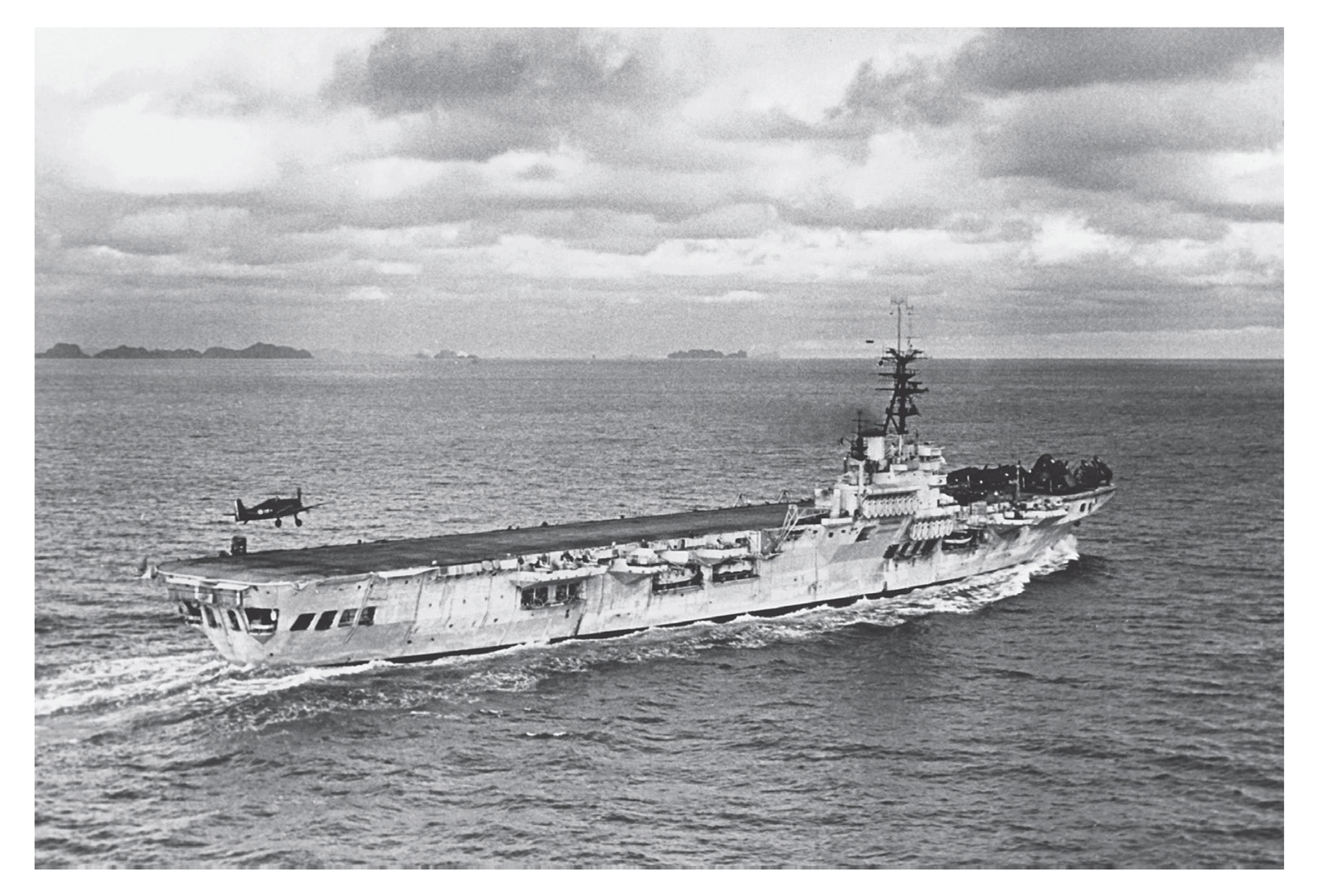

A Grumman F6F Hellcat of Squadron 1F landing on the French carrier Arromanches, Gulf of Tonkin, 1953.

The air war over Indochina was a decidedly one-sided affair. The Viet Minh did not have the ability to operate an air force, especially one with modern jet fighters. Nor did Mao offer them one. This was just as well for the French, who relied on slower propeller-driven aircraft throughout the conflict. In Korea, Soviet and Chinese-piloted MiG-15 jets operated south of the Yalu, intercepting American B-29 bombers targeting North Korea’s defence industries. This led to fierce aerial battles, though the communists ultimately failed to gain control of the air. The North Koreans were supplied the MiG, but they and their allies’ jet fighters had little bearing on the ground war as they spent much of their time locked in dogfights.

In contrast, America was soon providing the French with Second World War-vintage naval dive-bombers to support their ground war in Indochina. However, France’s greatest failing was its complete lack of a strategic airlift capability and the weakness of its tactical airlift. The French never really generated the ability to support more than one operation at a time, which was to have catastrophic results at Dien Bien Phu.

Once China and the Soviet Union had recognized the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the Viet Minh began to receive ever-growing quantities of Chinese and Soviet weapons.

A Grumman F6F Hellcat of Squadron 1F landing on the French carrier Arromanches, Gulf of Tonkin, 1953.

Subsequently, French reliance on fortified ‘hedgehogs’ meant aircraft played a key role in the escalating war, providing vital ground support and supplies. The French air force committed around 300 aircraft to Vietnam, while the French navy rotated four carriers with their naval air squadrons in the South China Sea.

Prior to the Second World War, the French Armée de l’Air (air force) and Aéronnautique Naval or Aéronavale (naval air force) had maintained only token units in Indochina. Most of the aircraft there were obsolete, consisting of 1925-vintage biplanes. At the outbreak of the war in 1939, the French had about 100 aircraft, of which just 13 were modern fighters. These accounted for 20 Thai aircraft during the brief border war with Thailand, but they could do nothing to counter the powerful Japanese air force.

The French air force first returned to Saigon on 12 September 1945, when Americanbuilt Douglas C-47 Skytrains ferried in 150 French troops to serve alongside the British. Subsequently, C-47 and Toucan (Ju 52 variant) transports were used to drop rudimentary barrel bombs on Viet Minh positions. On their return to Indochina, until 1949, the French feared that America might impose an embargo on spares for U.S.-made combat aircraft and thus greatly limit their deployment options. This concern, however, evaporated once Mao had taken over in China.

Ironically, the Nazi war machine helped equip the French armed forces. The trimotor Toucan was a hangover from the Second World War. While under Nazi occupation, France had been forced to build the German Junkers Ju 52 medium bomber and transport aircraft. These were constructed at the Amiot factory at Colombes. Post-war designated the AAC.1 Toucan, it was kept in production with over 400 built for Air France and the French air force. The drawback with the Toucan, and indeed the Skytrain, was the limited number of men they could carry: eighteen and twenty-eight respectively. This meant that parachute and air-landing operations required very large numbers of transport aircraft. In the Second World War, the Axis and Allies conducted such operations, but they always resulted in considerable losses in aircraft.

American-supplied F8F-1 Bearcat fighter-bombers first arrived in Indochina in January 1951. The airfield here is probably Tourane.

Similarly, occupied France built the German Fieseler Fi 156 Storch (Stork) reconnaissance aircraft, made famous by Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. It was also kept in postwar production as the Morane-Saulnier Criquet (Cricket). This proved ideal for Indochina because of its short take-off and landing capabilities, plus its low speed, which enabled it to use the roughest of air strips. The Criquet was deployed in Indochina by the French army, Armée de l’Air and Aéronavale for a wide variety of tasks.

The first fighter aircraft sent out were British-supplied Supermarine Spitfires, rather than the Armée de l’Air’s American-built Republic P-47Ds. While waiting for them, French pilots conducted hair-raising training flights in a dozen dilapidated and untrustworthy Japanese fighters. The Spitfires though, were not suitable for ground support due to their limited range and small bomb load. Nonetheless, they were flown from Saigon in Cochinchina, Nha Trang and Tourane (Da Nang) in Annam and Hanoi, and Lang Son in Tonkin until 1947. Likewise, the British-supplied, twin-engine de Havilland Mosquito proved ill-suited to the conditions, as the bonded-plywood structure had a habit of falling apart in the tropical heat. Confined to Saigon, they were eventually sent home.

To back up the Armée de l’Air the French navy sought to keep a carrier stationed off the coast of Vietnam, though these deployments really stretched its capabilities, operating so far from home. The escort carrier Dixmude (former HMS Biter) first arrived in the South China Sea in March 1947, with nine American-supplied Douglas SBD-5 Dauntless dive-bombers – the victors of the Battle of Midway in June 1942. These aircraft made their first carrier sorties on the 16th of that month, with additional raids against targets in Annam and Tonkin.

After problems with her launch catapult, Dixmude was forced to return to Toulon for repairs, thereafter making only one more combat deployment the following year. On the return journey, the vessel carried Toucans and Spitfires for the air force. The elderly carrier was then employed as an aircraft-transport vessel. Dixmude was photographed in 1950 on the Saigon River with a deck full of F6F-5 Hellcats.

The light carrier Arromanches (former HMS Colossus) arrived in November 1948, making a total of four combat deployments up to and including 1954. This carrier operated the American Curtiss SB2C-5 Helldiver dive-bomber. While it provided accurate and powerful support for the French ground forces, the Helldiver was vulnerable to ground fire. During these deployments, the aircraft usually operated from forward land bases rather than from the carrier.

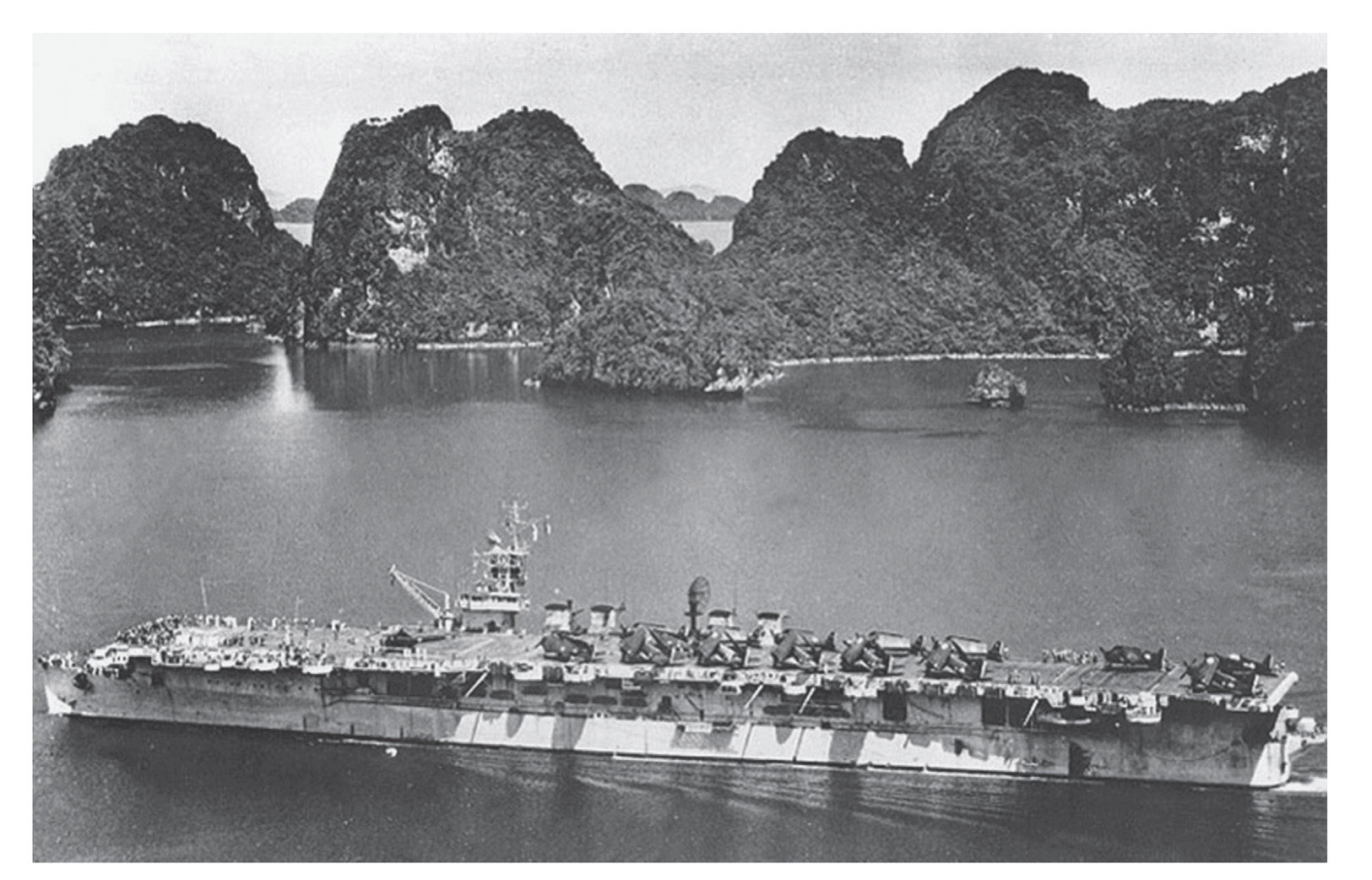

The third carrier committed to the war was La Fayette (former USS Langley), which took over in April 1953, minus its aircraft, ready to take on those from the Arromanches. It only stayed on station for five weeks.

The fourth and final carrier, Bois Belleau (former USS Belleau Wood), only operated from 30 April to 15 September 1954. The navy also deployed amphibious aircraft, such as the PBY Catalina, to patrol Vietnam’s coastal waters and the Red River Delta. Additionally, they acted in air-support, transport and medical-evacuation roles. These were replaced by the four-engine PB4Y Privateer, which was the largest aircraft operated by the French.

Once Mao was in power and the Korean War had broken out, Washington saw France less as an unsavoury colonial power with dubious democratic credentials, and more as a staunch anti-communist ally. The Spitfires were soon followed with American-supplied Bell P-63 Kingcobras, called ‘Kings’ by their French aircrews. These helped cover the ill-fated withdrawal from Cao Bang in the summer of 1950, but again, could not carry a large enough bombload and could not operate from forward airfields.

What arrived next was much better and just what the French needed. To re-equip French fighter units, the Americans provided the F6F-5 Hellcat and the F8F-1 Bearcat. Both these were designed as carrier strike aircraft, so were capable of relatively short takeoff and landing. This meant that they were ideal for forward deployment in Indochina. The Hellcats were delivered by U.S. carrier in November 1950 with the ‘Beercats’ as the French called them, following in January 1951.

The Hellcat was only intended as an interim solution until all the fighter squadrons could be equipped with the Bearcat – this conversion though, was not completed until early 1953. In contrast, the Bearcat remained in service until the final French withdrawal in April 1956, and fought at Dien Bien Phu. It became the premier fighter-bomber in Indochina, being used almost solely for ground-attack missions. Some ‘Beercats’ though, were converted to a reconnaissance role by fitting specially modified U.S. drop tanks fitted with two cameras.

In the French armoury was napalm. This jellied-petroleum bomb, developed by the Americans in the early 1940s, and used against the Japanese during the Second World War, was then employed by UN forces in Korea. This terrible weapon, which bursts on contact with the ground into a wide carpet of flame, generates enormous heat and, once stuck to skin, cannot be removed. Used as an anti-personnel weapon, it was devastating. The Bearcat was capable of dropping 100gal. napalm tanks. It was first used by the French on 22 December 1950, against a Viet Minh troop concentration at Tien Yen.

The French air force desperately wanted a twin-engine light bomber, but none was available. It especially needed such an aircraft once the Viet Minh’s air defences began to improve. The best available aircraft to fill this role was the American Douglas B-26 Invader, which was known as the A-26 until 1948. While the Bearcat and Hellcat were surplus to U.S. Navy requirements, the USAF was employing its B-26 as night bombers in Korea. Nonetheless, the first four aircraft were supplied to the French in early November 1950.

A Douglas B-26 Invader light bomber loaned by the U.S. to the French air force in Indochina. (Photo National U.S. Navy Museum)

An American B-26C invader dropping bombs over Korea in 1951. The French were first supplied this type of bomber three years earlier. (Photo USAF)

The B-26 was the most potent type of air power the French were able to bring to bear during the war, with the ability to carry 2,722kg of bombs, napalm or rockets, and armed with up to fourteen machine guns. Equipping a French bomb group, the B-26s were operated from Tourane. A further two bomb groups were later formed using this aircraft. Despite its growing strength and newfound confidence, the French air force was unable to provide the army with a decisive edge during the inconclusive Black River offensive in the winter of 1951–52. From then until the end of the war, America provided some eighty bombers, fighter-bombers and transport aircraft. Many of these, however, arrived too late to influence the outcome of the war.

Funds were not made available for the acquisition of limited numbers of helicopters from Britain until 1952. America also supplied some rotary-wing aircraft. The French army, air force and navy all deployed helicopters to support their operations. The Groupement des Formations d’Hélicoptères of the French army was created under Commandant Marceau Crespin. In honour of General de Lattre’s late son, who was killed in action, the French army’s main helipad at Tan Son Nhut air base outside Saigon was named Camp Bernard de Lattre. Army helicopter squadrons were also based at Bien Hoa to the north of Saigon. These were used almost entirely for medical evacuation rather than troop carrying. By the time of Dien Bien Phu, the French had just thirty-two helicopters, most of which were Sikorski S-55s, dubbed the H-19 by the French.

General Salan, relying on the strategy of les hérissons fortified ‘hedgehog’ bases and mobile commando operations, needed the commitment of massive airpower. By this stage, the air force had some 300 aircraft, including four groups of Bearcats and two of Invaders. This strength was to remain unchanged until after Dien Bien Phu, when the third bomb group was added.

After the withdrawal of the antiquated Toucans, there were three transport groups equipped with C-47s, providing logistical support for the ground troops. To supplement this insufficient fleet, the French made use of commercial- and American-supplied Fairchild C-119Cs, which were sent from Japan and Korea. Some aircraft were flown by American mercenaries, operating from Formosa. These civilian pilots could earn up to five times that of their counterparts in the Armée de l’Air. The French armed forces’ lack of a strategic airlift meant that to fly troops and equipment from France or the other colonies required the help of Air France. America also stepped in, transporting almost 1,000 military personnel from Paris to Saigon in April–May 1954.

By 1953, the key Armée de l’Air officers were General Charles Lauzin, commander of the French air force in Indochina, General Jean Dechaux, commander Tactical Air Group North (Tonkin), and Colonel Jean-Louis Nicot, commanding the air transport group. Army aviation came under Commandant Crespin, who was responsible for the limited helicopter units.

The French aircraft carrier La Fayette in Indochina waters, 1953. (Photo U.S. Navy)