In April 1953, Ho Chi Minh and General Giap sought to stretch the French Expeditionary Force in Tonkin even more, by spreading the conflict into northern Laos. The invasion by the 312th Division had two other goals: the capture of the valuable opium crop and joining forces with the neighbouring communist Pathet Lao guerrillas. Their route of attack ran from Tuam Giao, through Dien Bien Phu, over the border, and down the Nam Ou valley.

General Salan simply did not have any reserves available to reinforce Laos, so the French outposts there were instructed to hold on for as long as they could, while a sustainable defensive system was set up in the region. French resistance was on a line running north– south, centred on Moung Khoua, Luang Prabang, and on the Plaine des Jarres. The town of Luang Prabang in central northern Laos was particularly important as its sits on the junction of the Mekong and Nam Ou (not to be confused with Nam Oum) rivers.

Giap’s invasion of Laos was a very significant turning point in the war. Previously, the French had been able to largely confine the conflict to Tonkin, with them operating from Hanoi behind the security of the De Lattre Line. Now the le hérisson defence would have to be extended around Luang Prabang. It was a step too far.

Although the French Expeditionary Force by this stage in the war numbered 190,000 and the Vietnamese National Army was being formed, Salan had no troops to spare. In northern Vietnam alone he had 80,000 men holding 900 forts who were tied down by fewer than 30,000 Viet Minh, most of whom were peasant militia rather than regulars. This was the situation facing General Henri Navarre when he arrived in May 1953 to replace Salan.

Navarre realized that his immediate problems were much closer to home, so he and his staff set about formulating the so-called Navarre Plan. In southern Vietnam, the troublesome guerrilla war was containable and stable. In the north, the lack of reserves meant that he had nothing with which to counter any Viet Minh attacks in the Red River Delta. His only option was to withdraw some of the outlying garrisons so as to free up troops from static defence. He would eventually be able to muster some 30,000 mobile reserves, but that would take time, so he decided to sit out the 1953–54 campaigning season while developing the Vietnamese National Army. Once the Vietnamese were up to strength they could replace the French and French-led garrison forces in the delta. Washington agreed to support his plans with almost $400 million worth of military assistance. He determined to conduct a number of minor operations to keep Giap occupied before launching a decisive offensive in 1955.

After the departure of de Lattre, René Cogny, who had been on his staff, took a combat command, leading a division in Tonkin and a mobile group in the Red River Delta. Navarre now appointed him ground-forces commander in northern Vietnam. Both men were to subsequently fall out spectacularly over the handling of the battle of Dien Bien Phu.

In the meantime, in Peking, Mao and his advisers decided that they would settle, as they had in Korea, for a half measure in Indochina. By 1953, both sides in Korea, the North backed by China and the South with its United Nations allies, had fought themselves to a bloody standstill, leaving the country divided exactly as it had been before the conflict. The Chinese People’s Liberation Army, employing human-wave tactics, had suffered the most appalling casualties. Mao, during the Korean War, had called a halt to large-scale operations in Indochina so that China could focus her resources on Korea. When he took the decision to end the Korean conflict in May 1953, Mao immediately despatched Chinese officers directly from Korea to Indochina.

Mao was looking at the bigger picture: Ho must do enough to drive the French out, but not spark intervention by America. after China’s experiences in Korea, Mao was only too aware of the type of firepower the American military could bring to bear. Mao wanted a settlement in Indochina, even if it meant partition, but he did not tell the Viet Minh. He wanted them to escalate the war to a point where it created an irretrievable crisis for the French, but no more.

In July 1953, in northeastern Tonkin, Navarre attacked guerrilla bases in the Lang Son area with Operation Hirondelle, using three parachute battalions. These were then evacuated by sea. He also acted to secure his lines of communication in central Vietnam along the main north–south Route Coloniale 1. Despite a French operation the previous year, convoys on this road were regularly attacked by the Viet Minh’s 95th Regiment operating from a fortified region in the sand dunes and salt marshes between Quang Tri to the north and Hue to the south. This had led to the French dubbing the road la rue sans joie – the street without joy.

Under General Leblanc, the French gathered some 10,000 men for Operation Camargue, a combined ground, airborne and amphibious operation that was intended to trap the Viet Minh. The 3rd Amphibious Group deployed 160 tracked Crabs and Alligators to get their men ashore and into the dunes. Camargue commenced on 27 July 1953, the landings unopposed. The first resistance was met at Dong Que when the 6th Moroccan Spahis with M24 tanks, the 1st Battalion Moroccan Rifles and the 69th African Artillery Regiment were ambushed. They managed to destroy almost an entire Viet Minh company, but this delay enabled the rest of the 95th Regiment to retreat into the southern portion of the developing pocket.

At 10.45 am, to block the Viet Minh’s retreat, elements of the 2nd Battalion, 1st Parachute Light Infantry Regiment, were dropped near Dai Loc, from where they began to push towards the mouth of the Van Trinh Canal to close the pocket. Despite hazardous drop conditions caused by 48kph winds, the 3rd Vietnamese Parachute Battalion dropped near Lang Bao. This helped seal the southern escape routes. However, during the night of 28–29 July, most of the Viet Minh managed to slip the net. The ambitious operation was ended on 4 August, having been a modest success.

General Salan and Prince Sisavang Vatthana visiting the strategic Laotian town of Luang Prabang, May 1953.

During August, as part of Navarre’s reduction in exposed garrisons, Na San was evacuated. French air force transport aircraft were assisted by planes from three civilian companies in an effort to complete this mission as quickly as possible. Colonel Gilles conducted the withdrawal without loss, having duped the local Viet Minh. He slowly withdrew his units, collapsing his defences, until just a single battalion was left. A local Viet Minh officer at Na San recalled, ‘The enemy was able to escape and save its entire forces because of our poor intelligence.’

Nonetheless, it must have slightly rankled Gilles that having shed so much blood to secure the base, he was now asked to abandon it to the enemy.

That October, Mao got his hands-on France’s strategic intentions, when he obtained a copy of the Navarre Plan. China’s chief military adviser to Indochina, General Wei Guo-qing, flew from Beijing, handing this to Ho Chi Minh in person. It was this intelligence that convinced Ho to give battle at Dien Bien Phu, although the plan made no mention of the place. It is unclear how this vital intelligence coup occurred, but a copy of the Navarre Plan had been passed to the Americans.

By November 1953, the French position in Indochina had slightly improved, and Navarre began contemplating taking the battle to Giap once more. Disrupting Giap’s supply lines seemed the best option, as this would curtail the Viet Minh’s war effort. This, however, would require a mission deep into the Viet Bac and, in view of the failure of Operation Lorraine, was not an enticing prospect. Countering Giap’s unwelcome activities in Laos seemed to offer a better chance of success, especially if the Na San base aéro-terrestre could be repeated to good effect.

Looking at his situation maps, Navarre understood that if his men could dominate the invasion routes into Laos, this would cut off the Viet Minh threatening Luang Prabang. This would either force Giap to fight or withdraw. The best place to block Giap was at Dien Bien Phu, known as Muong Than in T’ai, and the flat valley formed by the Nam Youm river in the T’ai mountains. The region, although dominated by the Viet Minh, was still supportive of the French. Also, the T’ai capital of Lai Chu north of Dien Bien Phu, although cut off, was held by French-officered local units.

Initially, Operation Castor and the seizure of Dien Bien Phu as a base aéro-terrestre was intended to distract Giap from Lai Chu and so relieve the T’ai units ready for an evacuation with Operation Pollux. Once French paratroops had linked up with the T’ais they would use Dien Bien Phu as a ‘mooring point’ from which to attack the Viet Minh’s rear areas. This was a terrible gamble because Dien Bien Phu had no ground link with other French garrisons and was 275km by air from Hanoi. Nonetheless, the success at Na San indicated that a garrison could be kept resupplied.

To facilitate Castor, Navarre gathered an initial spearhead of French and Vietnamese paratroops with full combat kit at the Giam-Lam and Bach-Mai airfields just outside Hanoi. These men were under the command of seasoned veterans of the Indochina War, majors Marcel Bigeard, Jean Brechignac and Jean Souquet. On the runways were sixty-seven C-47 Skytrain transport aircraft. Another aircraft carrying Lieutenant General Pierre Bodet, Brigadier General Jean Decheaux and newly promoted Brigadier General Jean Gilles was soon circling over a drizzle and mist shrouded Dien Bien Phu. On their command, three parachute battalions were poised to attack, with the task of seizing three drops zones dotted through the valley.

Vietnamese National Army on parade, Hanoi, 1951. (Photo Huyme)

Fatefully, on 20 November 1953, Airborne Battle Group 1, consisting of the 1st and 6th colonial parachute battalions and the 2nd Battalion, 1st Chasseurs Parachute Regiment, jumped over the northern and southern drop zones designated ‘Natasha’ and ‘Simone’ respectively. Major Bigeard’s 6th Colonial Parachute Battalion, landing at ‘Natasha’, unexpectedly encountered some resistance from Viet Minh regulars who were in the valley undergoing training. Bigeard recalled, ‘When we came down on November 20 were told there would be no Vietnamese. But there were two companies exactly where we jumped. Some of my men were killed before they even touched the ground, others were stabbed where they landed.’

His men, recovering tons of equipment, found that many of their radios had not survived the drop and some of their mortars were missing. Bigeard, gathering three of his four companies, and without waiting for support, attacked Dien Bien Phu village. He was met by resistance from Viet Minh regulars of the 148th Regiment, but at 3.00 pm, Souquet’s 1st Colonial Parachute Battalion, who had jumped in support, arrived to help. The Viet Minh withdrew in good order and the villagers fled into the mountains. French losses for the day proved to be light, with thirteen dead and forty wounded.

A second force of paratroops jumped into the valley the following day, 21 November, with their commanding officer Lieutenant Colonel Pierre Langlais, who injured a leg, and the overall commander of the operation, Brigadier General Gilles. The Airborne Battle Group 2 comprised the 1st Foreign Legion Parachute, 5th Vietnamese Parachute and the 8th Parachute Assault battalions. A third drop zone, called ‘Octavie’, was used further south to deliver heavy supplies. The parachute of one of the two bulldozers dropped failed to open fully and it buried itself into the ground.

By 22 November, after the arrival of a fresh battalion of Vietnamese, there were 4,560 troops at Dien Bien Phu. Langlais, much to his irritation, was airlifted back to Hanoi to get his leg plastered, returning several weeks later.

The paras set about securing the heart-shaped valley, which is 19km long and 13km wide and surrounded by heavily forested hills. They had possession of the village of Dien Bien Phu and a nearby airfield west of the Nam Youm, plus a second one on the east bank to the south of Ban Long Nhai. The first was quickly refurbished, ready for the first C-47 transport aircraft that would form the vital lifeline for the isolated garrison. Defences were also built, while patrols pushed into the hills. At the end of the month, the paras began to pull out to be replaced by infantry. It was now that Giap responded, despatching his 308th and 312th divisions towards the valley.

The first indication that Operation Castor was not destined to go well occurred with the withdrawal from Lai Chau. Although the town had acted as a useful base of operations, it was indefensible, sitting as it did in a valley at the confluence of the Black and Nam Na rivers. It only had a small, exposed dirt airstrip that was prone to flooding. The only other way in and out was by means of a narrow jungle track.

When Lieutenant Colonel Trancart, the French commander at Lai Chau, was told of the planned evacuation in mid-November, he immediately despatched the 700-strong 1st T’ai Partisan Mobile Group to Dien Bien Phu. After a week-long march and a series of communist ambushes, they finally reached their destination. The mobile group’s departure clearly signalled that General Cogny viewed the defence of Lai Chau as untenable, particularly now that Giap’s 316th Division was bearing down on the town.

French troops in a damaged village near the Plaine des Jarres, May 1953.

Operation Pollux commenced on 7 December, when generals Cogny and Gilles landed in Lai Chau to personally break the bad news to Deo Van Long, president of the T’ai Federation. French aircraft transported the 301st Vietnamese Infantry Battalion, a paratroop company, elements of the 2nd Moroccan Battalion, 7th Company, 2nd T’ai Battalion and 327 Senegalese of the headquarters staff from the town in over 180 flights. Deo Van Long and his entourage were flown to Hanoi and exile.

To local communist spies, it was all too obvious what was going on. Trancart departed on 10 December after overseeing the destruction of 300 tons of ammunition and 40 vehicles that could not be salvaged. Some 400 mules and pack horses were abandoned. When Giap’s 316th Division moved into Lai Chau two days, later they found the French Tricolore still defiantly flying.

Tragically, some 2,100 T’ai irregular light infantry and 36 Europeans were left behind, with the impossible task of fighting their way to Dien Bien Phu. They should have gone earlier with the 1st T’ai Partisan Mobile Group. Instead, many of the remaining T’ai, faced with the prospect of leaving their homes, deserted. The rest, divided into four groups and armed with only rifles, sub-machine guns and a few mortars, were constantly harassed and ambushed by communist and pro-communist forces. They were kept resupplied by air drop.

Seven companies under Lieutenant Guillermit became trapped at Pa Ham Pass and were overrun on 10 December, with just 150 men under Sergeant Arsicaud escaping to Muong Tong, 15km south of Lai Chu. There, 600 irregulars gathered before heading south, hoping to catch Lieutenant Ulpat’s column, which included women and children. On 18 December, Dien Bien Phu informed Arsicaud that Ulpat’s men, who were just a day’s march ahead of him, had been wiped out. His force them came under attack that night and vanished.

Sergeant Blanc, with three other companies as well as elements of the Partisan Mobile Group and dependents from the Vietnamese battalion, were trapped at Muong Pon, 70km from Lai Chu. He tried to get the women and children to a relief column formed by the 2nd Airborne Group that was fighting its way northwards towards him, but failed. His force disappeared while under attack during the night of 12–13 December. The relief column arrived in Muong Pon to find it deserted. Of the twenty T’ai companies that had marched out of Lai Chu, the remains of barely half a dozen reached Dien Bien Phu, with just 175 men.

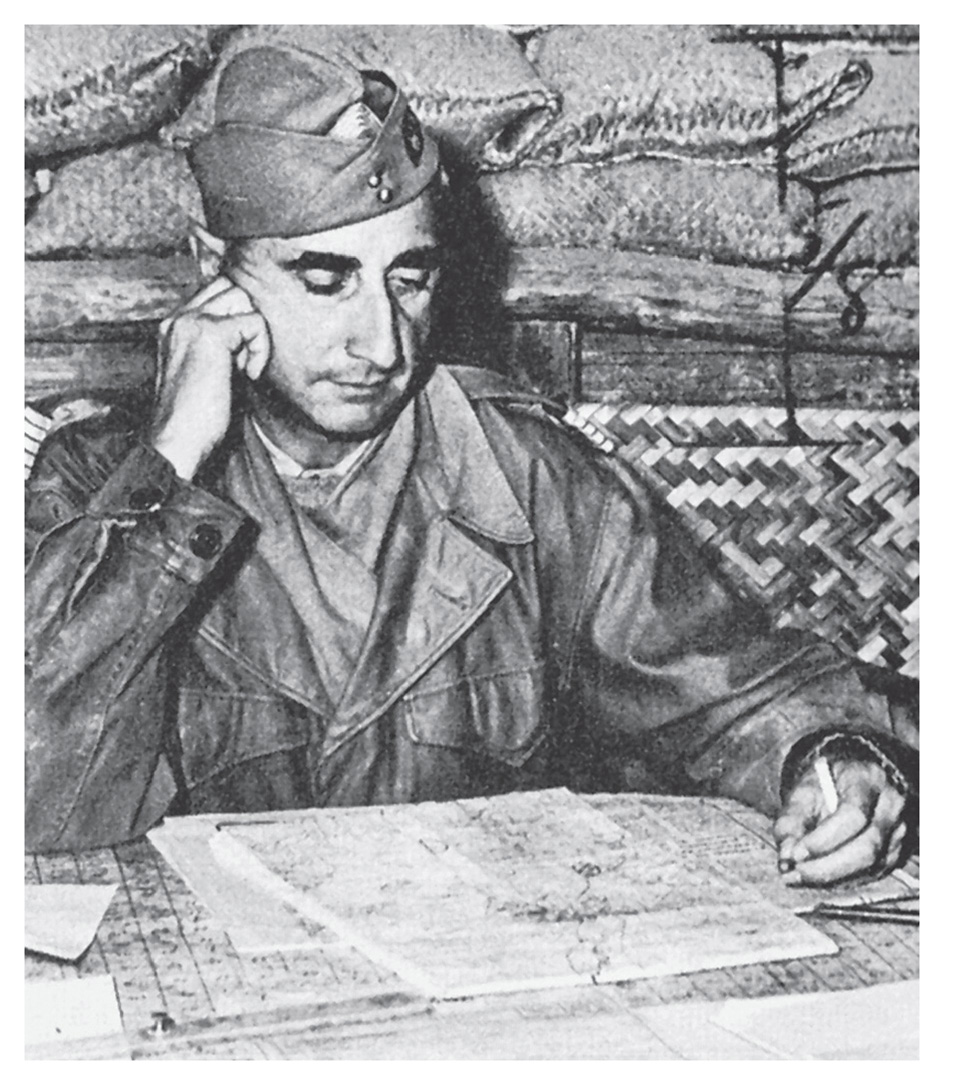

Colonel de Castries, the French garrison commander, Dien Bien Phu.

The 2nd Airborne Group also had to fight its way back. In an ominous taste of things to come, reconnaissance aircraft and fighter-bombers supporting it reported being hit by anti-aircraft fire.

The 2nd Airborne Group under Langlais conducted another reconnaissance raid on 23 December, with the aim of linking up with Laotian light infantry and Moroccan Tabors from Laos. The rendezvous point was the Laotian town of Sop Nao, which was in a very mountainous area, thick with jungle and ideal for ambush. Although the link-up was effected two days later, the task force was harried by a mobile enemy and had to return by a far worse route. This again showed that offensive operations conducted from Dien Bien Phu were almost impossible, due to the presence of the enemy and the extremely unforgiving terrain.

Upon gaining intelligence on Giap’s movements, Navarre and Cogny began to reconsider their plans. It seemed that Dien Bien Phu might act as bait from where the French could crush the Viet Minh, or at least act as a diversion in anticipation of an attack on the Red River Delta. Also, the almost complete destruction of the T’ai units meant that the original plan to use it as a rallying point was now completely redundant. Dien Bien Phu went from a forward operating base to a fortified camp, defended by a series of armed positions in the same manner as Na San. By the end of the year, there were almost 5,000 French troops at Dien Bien Phu. The scene was set for the decisive battle of the First Indochina War.

Beginning in May 1953, America lent the French six Fairchild C-119 Flying Boxcars.

All grossly underestimated Giap’s capabilities: in Saigon, General Navarre, Lieutenant General Pierre Bodet, his deputy commander-in-chief, General Lauzin, commander of the French air force in Indochina, and Colonel Jean-Louis Nicot, commanding the Indochina air transport group, and in Hanoi, General Cogny and General Jean Dechaux, commander Tactical Air Group North Crucially, they failed to take fully into account the growing power of Giap’s artillery and anti-aircraft units, nor did they appreciate his considerable logistical support. They could not conceive that Giap would commit five divisions to Dien Bien Phu. Nor could they conceive that the Viet Minh could capture the surrounding hills and lug their heavy artillery up onto them. If that happened, the French would not be fighting a mobile battle from a fortified base, but instead they would be facing a siege.

General Navarre’s hands were now tied, as he noted:

When I occupied Dien Bien Phu I expected to have to deal with two divisions, then eventually two and a half, three … It was not until 20 December that I learned we would actually be dealing with four divisions. At that point it was too late to evacuate Dien Bien Phu … If I had withdrawn I would have lost all our men and supplies.

Communist anti-aircraft guns included old Second World War German MG34s.